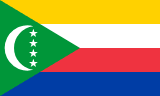

Comoros

Comoros exhibits low range performance across three categories of the Global State of Democracy Framework (Representation, Rights and Rule of Law), and mid-level performance in Participation. It is among the bottom 25 per cent with regard to several factors of Rights, Representation, Rule of Law and Participation. Over the last five years, there have been declines in Access to Justice and Freedom of the Press. Comoros, a low-income country, relies heavily on subsistence agriculture and fishing, supported by high levels of remittances and foreign aid. Despite the creation of ‘safety net’ programmes in recent years, widespread poverty and underdevelopment persist. These ‘Perfume Islands’ are among the most climate-vulnerable in the world.

The history of Comoros reflects a rich cultural tapestry, with early settlers arriving from various regions, including Malayo-Indonesians and Bantu-speaking Africans. Arab traders further influenced the island, introducing Islam, which remains the dominant religion. France took control of all four islands in 1886. In 1975, the three westernmost islands attained independence, while the fourth, Mayotte, chose to remain French.

Since independence, Comoros has faced chronic political instability and repeated coups d’état, largely fueled by inter-island division. In 1997, the islands of Anjouan and Mohéli attempted, unsuccessfully, to secede, dissatisfied with the perceived dominance of Grand Comore island. The 2001 Fomboni Accordsintroduced a new constitution, promoting renewed, if fragile, stability through decentralization and a rotating presidency between the three islands. Despite the power-sharing agreement, President Azali Assoumani leveraged a 2018 referendum, widely boycotted by the opposition, to abolish the rotation and extend his term limits, consolidating power and triggering increased political violence, including assassination attempts and repression of dissent. The 2019 and 2024 elections were marred by fraud allegations and irregularities, with the opposition disputing the result. In September 2024, Assoumani survived a knife attack by a soldier during a public event, intensifying political tensions amid growing backlash against his rule. Against the backdrop of Assoumani’s growing authoritarianism, Comoros has experienced suppression on free expression and media, and a crackdown on dissent – actions that are part of a larger erosion of democratic institutions across the country.

Comoros continues to face significant socio-economic challenges. Poverty remains widespread, exacerbated by chronic underinvestment in health and education, which places the country among the lowest-ranked on the Human Capital Index. These systemic issues, along with endemic corruption, have led to substantial migration of Comorians to Mayotte, contributing to brain drain.

Gender inequality is another critical issue. Comoros ranks among the worst-performing countries in terms of Gender Equality, with alarming rates of child marriage—around 30 per cent of girls marry before the age of 18. Gender-based violence is widespread, and there is little accountability for such crimes. Same-sex relationships are criminalized, although this law is rarely enforced. Religious freedom in Comoros remains limited under a constitution that enshrines Sunni Islam as the state religion, restricting public practice and proselytizing of other faiths, though recent years have seen fewer reports of surveillance or violence.

Looking forward, it will be important to continue to monitor Freedom of Expression, Freedom of the Press and Freedom of Association and Assembly in light of the repression of protesters, political opponents and the media during President Assoumani’s previous term. Similarly, corruption remains widespread and raises concerns about the Rule of Law, particularly as measured by Absence of Corruption.

Last updated: June 2025

https://www.idea.int/democracytracker/

February 2025

Ruling party wins legislative elections amid opposition boycott

On 12 January, Comoros held parliamentary elections, with the Convention pour le Renouveau des Comores (CRC) winning 28 out of 33 seats, according to the Independent National Election Commission. Voter turnout was recorded at 66.3 per cent, compared to 70.9 per cent in 2020. Several opposition parties either boycotted the vote or rejected the results because of concerns over its transparency. On 22 January, the Supreme Court annulled results in four constituencies due to procedural irregularities, including changes to polling station members, ballot box issues, and inconsistencies in official records. This led to a re-run in the four constituencies on 16 February, marking only the second time such a measure has been taken in Comoros, the last being in the 2016 presidential election. The final results from the four constituencies have yet to be published.

Sources: Commission Electorale Nationale Indépendante, International Foundation for Electoral Systems, Radio France Internationale (1), Radio France Internationale (2), Reuters, Jeune Afrique

September 2024

President survives knife attack

In a context of growing opposition to his presidency, Comoros President Azali Assoumani survived a knife attack during a public event on 13 September. The assailant, who managed to breach security, was identified as a 24-year-old soldier. The following day, the attacker was found dead in his prison cell under unclear circumstances. This incident has heightened political tensions in Comoros, where Assoumani has faced growing opposition due to concerns over his extended time in power and alleged efforts to suppress political dissent. The President has a history of surviving assassination attempts, with the most recent ones occurring in 2019 and 2020. An investigation has been launched to determine the cause of the attacker’s death.

Sources: AP News, BBC, Le Monde, Jeune Afrique, The East African, Bloomberg

August 2024

President grants son sweeping new powers

In August 2024, Comoros President Azali Assoumani granted his son, Nour El Fath Azali, significant authority over government affairs, sparking fears of dynastic control. El Fath was appointed secretary general of the government on 1 July, a role traditionally administrative but greatly expanded by decree on 6 August. With his new powers, the secretary general of Comoros must approve all decrees issued by ministers and governors of the three islands before being officially published and enacted. The decree also allows El Fath to intervene at all stages of government decision making. Critics believe this move elevates El Fath’s role to that of de facto prime minister. The expansion of El Fath’s role has raised alarms over the continued erosion of democratic governance in Comoros, with human rights groups warning of weakened political checks and balances as well as a significant increase in authority.

Sources: Jeune Afrique (1), Jeune Afrique (2), Reuters, RFI, France24

January 2024

Azali Assoumani re-elected in presidential election

Comoros held elections for the national presidency and the governors of the three largest islands on 14 January. The Independent National Election Commission (Commission Electoral National Independante, CENI) reported that the incumbent president Azali Assoumani won re-election in the first round, receiving 62.97 per cent of the valid votes. CENI reported presidential election turnout to be 16.30 per cent, while turnout in the gubernatorial elections varied between 39.13 per cent and 69.56 per cent. There were six candidates for president, all of whom are men. There was only one woman among the 26 candidates for governor: Chamina Ben Mohamed who won the governorship of Mohéli. A joint election observation mission from the African Union and Eastern African Standby Force noted political tensions during the early part of the electoral process but described elections as taking place in a peaceful atmosphere, and found few logistical or procedural problems in the management of the election. Opposition candidates’ legal challenges to the election were dismissed by the Supreme Court. The Court released revised figures for the election, finding that President Assoumani received 57.2 per cent of the votes, with turnout much higher than reported by the CENI at 56 per cent. This would be slightly up from the last presidential election in 2019 which had 53 per cent turnout.

Sources: Commission Electoral National Independante (1), Commission Electoral National Independante (2), African Union and Eastern African Standby Force, The East African, Radio France Internationale

Riots, a curfew, and Internet shutdown after contested election

Comoros’ capital city, Moroni, was rocked by riots in the days after the official result of the presidential election was announced by the Independent National Election Commission (Commission Electoral National Independante, CENI) on 16 January. The CENI reported that incumbent President Azali Assoumani had been re-elected for a fourth term, in an election with only 16.3 per cent turnout. Opposition candidates alleged that the election was manipulated through fraud and the stuffing of ballot boxes. Demonstrations against the official result of the election turned violent as demonstrators blocked roads, burned vehicles, set fire to the home of a government minister, and looted shops and a food depot. The police responded with force, including the use of tear gas. One protestor was reported to have been killed and at least 25 injured. A curfew was ordered, the army was deployed to keep order, and Internet access was disrupted.

Sources: France24, Al Jazeera, Associated Press, Access Now

See all event reports for this country

Global ranking per category of democratic performance in 2024

Basic Information

Human Rights Treaties

Performance by category over the last 6 months

Global State of Democracy Indices

Hover over the trend lines to see the exact data points across the years

Factors of Democratic Performance Over Time

Use the slider below to see how democratic performance has changed over time