Croatia

Croatia performs in the high range for Representation and exhibits mid-range performance in the other three categories of the Global State of Democracy (GSoD) framework. It ranks amongst the top 25 per cent of countries in the majority of Representation factors as well as in several factors of Rights (including Civil Liberties), and of Rule of Law (Personal Integrity and Security and Judicial Independence). Between 2019-2024, there were no significant changes in the country. Croatia has a service-based economy, with tourism being its most important branch.

Croatia became a kingdom in the 10th century and was divided between the Habsburg Monarchy, Ottoman Empire, and Venice from the 15th to 18th centuries. After WWII, Croatia became a federal republic within Yugoslavia. Declaring independence in 1991, Croatia faced a rebellion from Croatian Serbs supported by the Yugoslav People's Army and Serbia, with fighting effectively ending in 1995. For over a century, Croatian politics has been shaped by conflicts over national identity and the role of religion and tradition. These divisions evolved through critical historical events, including the formation of Yugoslavia, WWII and post-war communism, and the 1990s independence war. Croatia is an ethnically and religiously diverse country, with Serbs being the largest minority group, followed by Bosniaks and Roma. Discrimination against minority groups, including Serbs and Roma, persists in the form of hate crimes and hate speech.

The Catholic Church, which represents Croatia’s most sizeable religious community, plays a significant role in society. The country has struggled with depopulation and massive emigration, and brain drain has been named as an existential issue in recent years. The recent surge in migrant arrivals created another significant societal cleavage, with the country facing accusations of mistreatment and pushback of migrants.

Croatia faced corruption scandals involving political elites, leading to politicization of institutions and dissatisfaction. This has been exacerbated by disputes over the balance of power between politicians and the judiciary. Concerns persist about the political independence of the public broadcaster HRT, along with pressures, attacksand threats on journalists. Croatia is among the EU member states with the highest number of strategic lawsuits against public participation (SLAPPs), which are used to intimidate and pressure the press. In 2024, the ruling coalition passed a controversial law against whistleblowers.

Despite high performance in Gender Equality, constitutional guarantees and legislative progress, Croatia faces ongoing gender-based inequality, with persistent gaps in work, money, knowledge, time, power, and health. Abortion, while legal, is often inaccessible due to pressure from religious and neo-conservative groups. A 2013 referendum banned same-sex marriage, and discrimination and hate speech against LGBTQIA+ individuals persist. However, there have been advancements, such as rulings allowing same-sex couples to provide foster care (2020), adopt children (2021), and legal actions against extremist vigilantes (2022 and 2023).

Looking ahead, it is crucial to watch the Rule of Law, especially Absence of Corruption and Judicial Independence, given high-level corruption and accountability issues. Attention is needed for Freedom of the Press, given journalist intimidation and SLAPPs. Focus on Gender Equality, Economic Equality, and Social Group Equality is vital, considering ongoing gender inequality, barriers to abortion, and discrimination against minorities, migrants, and the LGBTQIA+ community. Lastly, Basic Welfare must be watched due to depopulation and brain drain challenges.

Last updated: July 2025

https://www.idea.int/democracytracker/

December 2024

Presidential elections fall short of establishing majority in first round

On 29 December, Croatia held the first round of its presidential elections, but no candidate secured a majority. A run-off will take place on 12 January. Incumbent President Zoran Milanović, backed by the Social Democratic Party (SDP), received the most votes with 49.1 per cent. Dragan Primorac, the candidate of the Croatian Democratic Union (HDZ) of Prime Minister Andrej Plenković, came second with 19.4 per cent and will challenge Milanović in the second round. Voter turnout was 46.0 per cent.

UPDATE: On 12 January, Croatia held the second round of its presidential elections. The incumbent President Zoran Milanović, backed by the Social Democratic Party (SDP), garnered 74.7 per cent of the vote, whereas the ruling centre-right Croatian Democratic Union, HDZ candidate, Dragan Primorac, secured around 25.3 per cent of the vote. Voter turnout was 44 per cent.

Sources: Balkan Insight, Politico, State Election Commission, International IDEA

New Sources: Hrvatska Radiotelevizija, Balkan Insight, State Election Commission, International IDEA (1), International IDEA (2)

April 2024

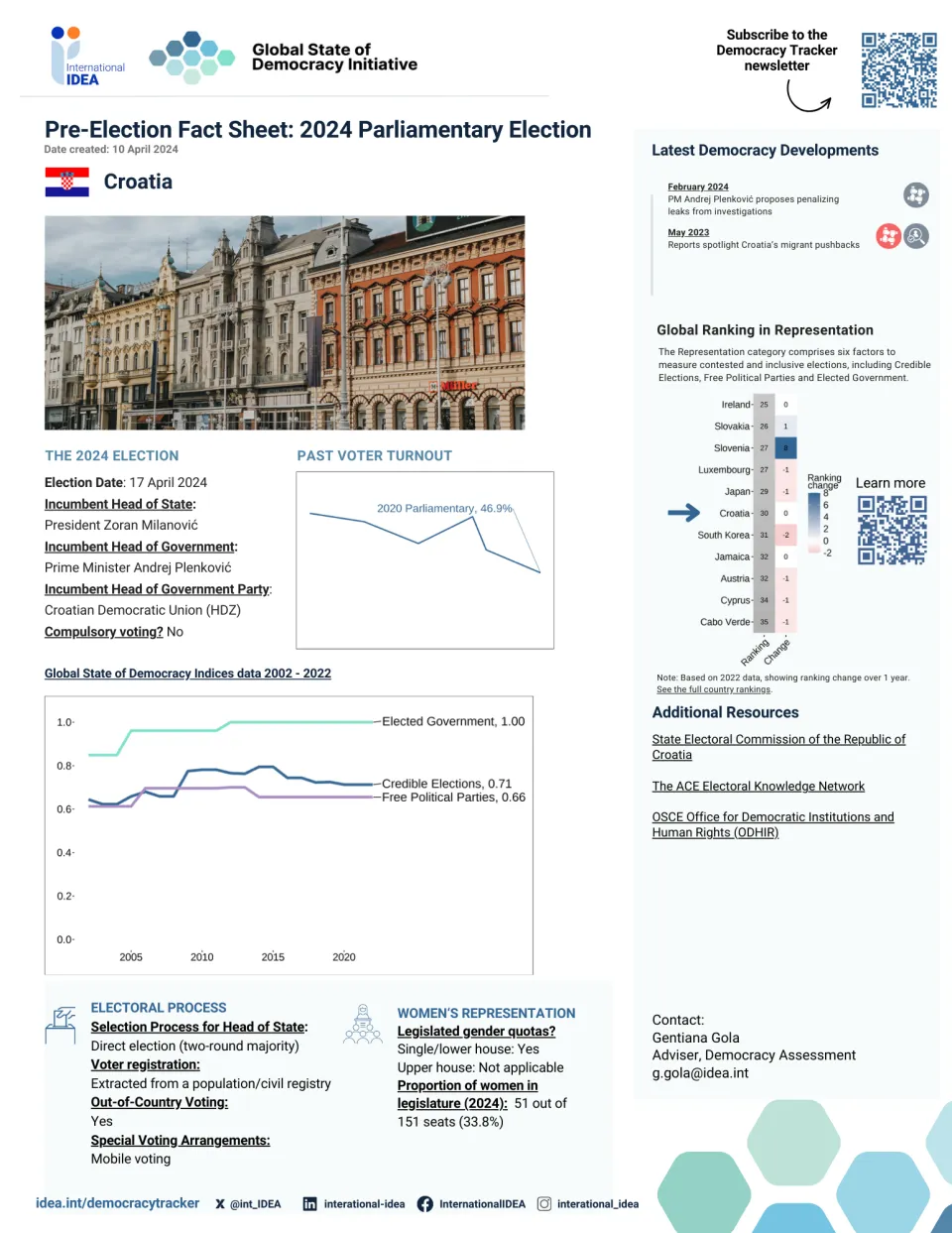

Conservative incumbent HDZ party wins parliamentary elections

In the parliamentary elections held on 17 April, the conservative Croatian Democratic Union (HDZ) remained the largest group with 34.4 per cent of the vote (winning 61 out of 151 seats, six fewer than they won in 2020), while the Social Democratic Party (SPD) coalition came second with 25.4 per cent of the vote. The right-wing party, Homeland Movement was third with 9.6 per cent. The campaign featured Prime Minister Andrej Plenković (HDZ) versus President Zoran Milanović (SDP). Women won 24.5 per cent of parliamentary seats, totaling 37 seats, an increase of two from 2020, marking the highest number since the country gained independence. Voter turnout was 62.3 per cent, up from 46.9 per cent in 2020.

Sources: State Election Commission (1), State Election Commission (2), Reuters, The Association of the Balkan News Agencies Southeast Europe, International IDEA (1), International IDEA (2)

March 2024

President Milanović defies Constitutional Court's ban on his PM candidacy

After President Zoran Milanović declared his intention to run for Prime Minister in the 17 April elections on behalf of the Social Democratic Party (SDP), the Constitutional Court asserted that Milanović could only pursue this candidacy if he resigned from his presidential position first. This decision was based on Article 96 of the Constitution, which prohibits the president from engaging in any other public or professional duties, emphasizing the non-partisan nature of the role and the prohibition of involvement in political party activities. President Milanović said that the Constitutional Court cannot do anything to him, that he would disregard its warning and that a potential annulment of elections by the Court would amount to a coup. Subsequently, he faced accusations of employing campaign rhetoric, prompting the State Election Commission to urge the President to abstain from direct involvement in election campaigning.

Sources: Hrvatska radiotelevizija (1), Hrvatska radiotelevizijav (2), Hrvatska radiotelevizija (3), N1 Info, Balkan Insight

Parliament approves controversial “anti-leaks” amendments to Criminal Code

On 14 March, Parliament approved “anti-leaks” amendments to the Criminal Code, despite petitions and protests from journalists and civil society. Article 307a states that anyone involved in a judicial or criminal proceeding who discloses non-public information without authorisation may face up to three years in prison. Journalists are exempt from being charged. The bill, proposed by Prime Minister Andrej Plenković, passed with the support of the ruling Croatian Democratic Union (HDZ) party. Critics argue that the amendments restrict freedom of speech, restrict access to information, and conceal corruption. The government said the aim is to "safeguard the presumption of innocence" and "protect the personal rights of those under investigation." The amendments, signed by President Zoran Milanović, took effect in March, though the President has criticized them and stated he would pardon anyone convicted for leaking information.

Sources: Narodne Novine, President of the Republic of Croatia, Deutsche Welle, ARTICLE 19

February 2024

PM Andrej Plenković proposes penalizing leaks from investigations

Prime Minister Andrej Plenković proposed amendments to the Criminal Code, which would make unauthorized disclosure of materials from criminal proceedings punishable by up to three years in prison. President Zoran Milanović, media and law experts have condemned the amendments. The Croatian Journalists’ Association (HND) said the legislation will silence journalists and their sources and see it as an attack on freedom of speech and the public interest. The International Press Institute said that this proposal, along with the July 2023 draft of the new media law, are a step backward for press freedom ahead of the 2024 elections. The legislation comes following a recent leak of text messages from a legal procedure that led to Prime Minister Plenković being accused of involvement in corruption.

Sources: Balkan Insight (1), Balkan Insight (2), Croatian Parliament, People’s Dispatch, International Press Institute, Politico

See all event reports for this country

Global ranking per category of democratic performance in 2024

Basic Information

Human Rights Treaties

Performance by category over the last 6 months

Election factsheets

Global State of Democracy Indices

Hover over the trend lines to see the exact data points across the years

Factors of Democratic Performance Over Time

Use the slider below to see how democratic performance has changed over time