Chad

Chad exhibits low-range performance across all four categories in the Global State of Democracy’s framework, with factor scores predominantly in the bottom 25 per cent globally. Compared to 2019, Chad has experienced declines in Elected Government and Judicial Independence. Oil production accounts for roughly 70 per cent of all exports and 15 per cent of the GDP. The country struggles with a high poverty rate and food insecurity, both of which have been compounded by extensive flooding, climate change-driven desertification, and internal instability. Due to regional instability, Chad hosts almost two million refugees.

Once part of the Kanem-Bornu Empire, Chad endured violent French colonial rule between 1900 and 1960. At independence, it inherited a weak state, hobbled by limited infrastructure, arbitrary borders and a fragmented administrative system designed to foment ethnic competition. The pattern of authoritarianism and instability that has characterised Chad’s governance since independence was set by the country’s first president, François Tombalbaye, whose rule was marked by political repression, regionally-based patronage, and armed conflict.

Since 1990, the country has been ruled by the Déby family through the Patriotic Salvation Movement, with former President Idriss Déby having seized power that year via a coup d’état. Lacking the state capacity to deliver basic services and exert territorial control, it has maintained power largely by repressing dissent and balancing and co-opting local power brokers. Chad’s chronic instability and fragility has helped make the military a highly influential actor and its importance has grown in recent years as the government battles insurgencies in the west (Boko Haram), and rebel groups along its northern and eastern borders.

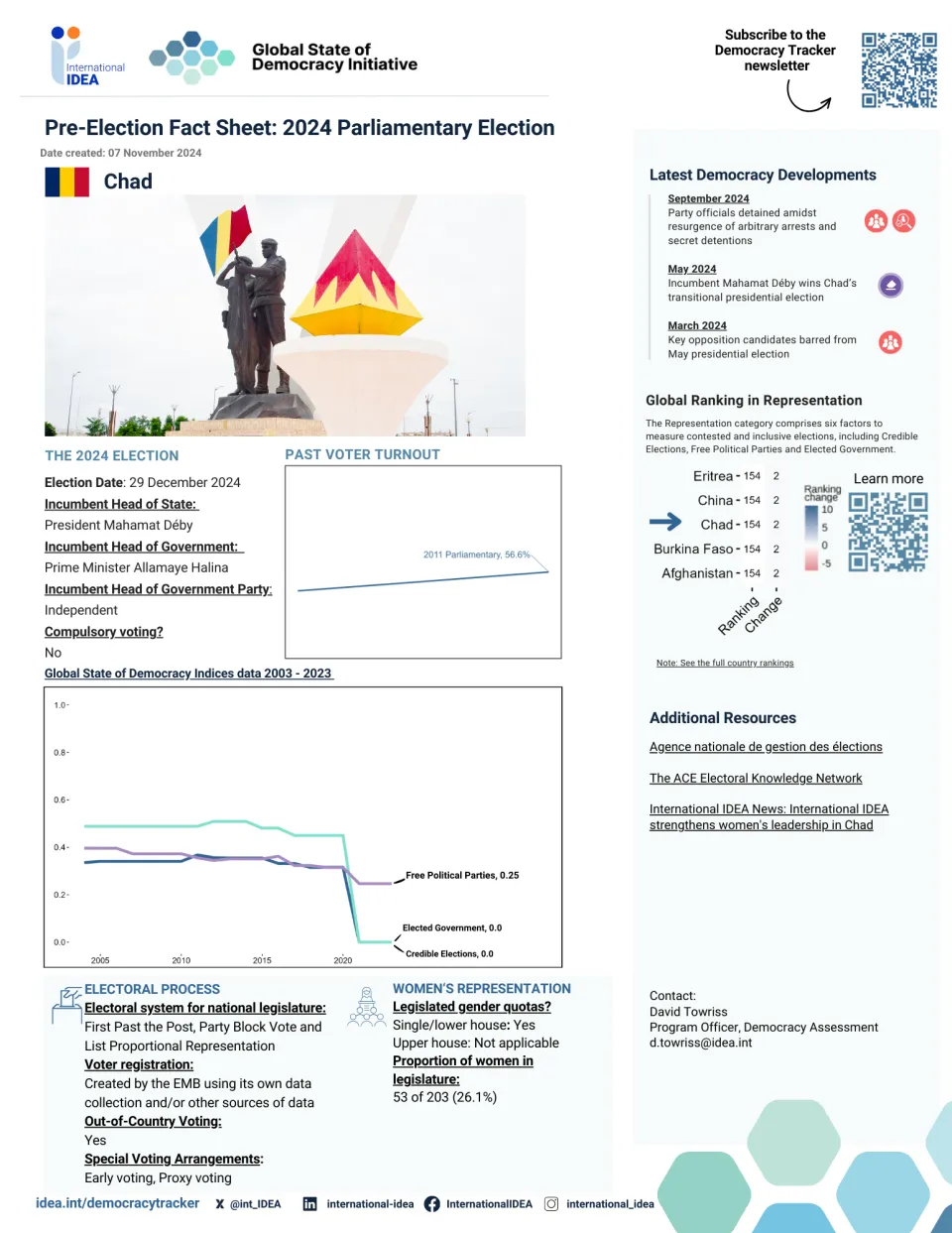

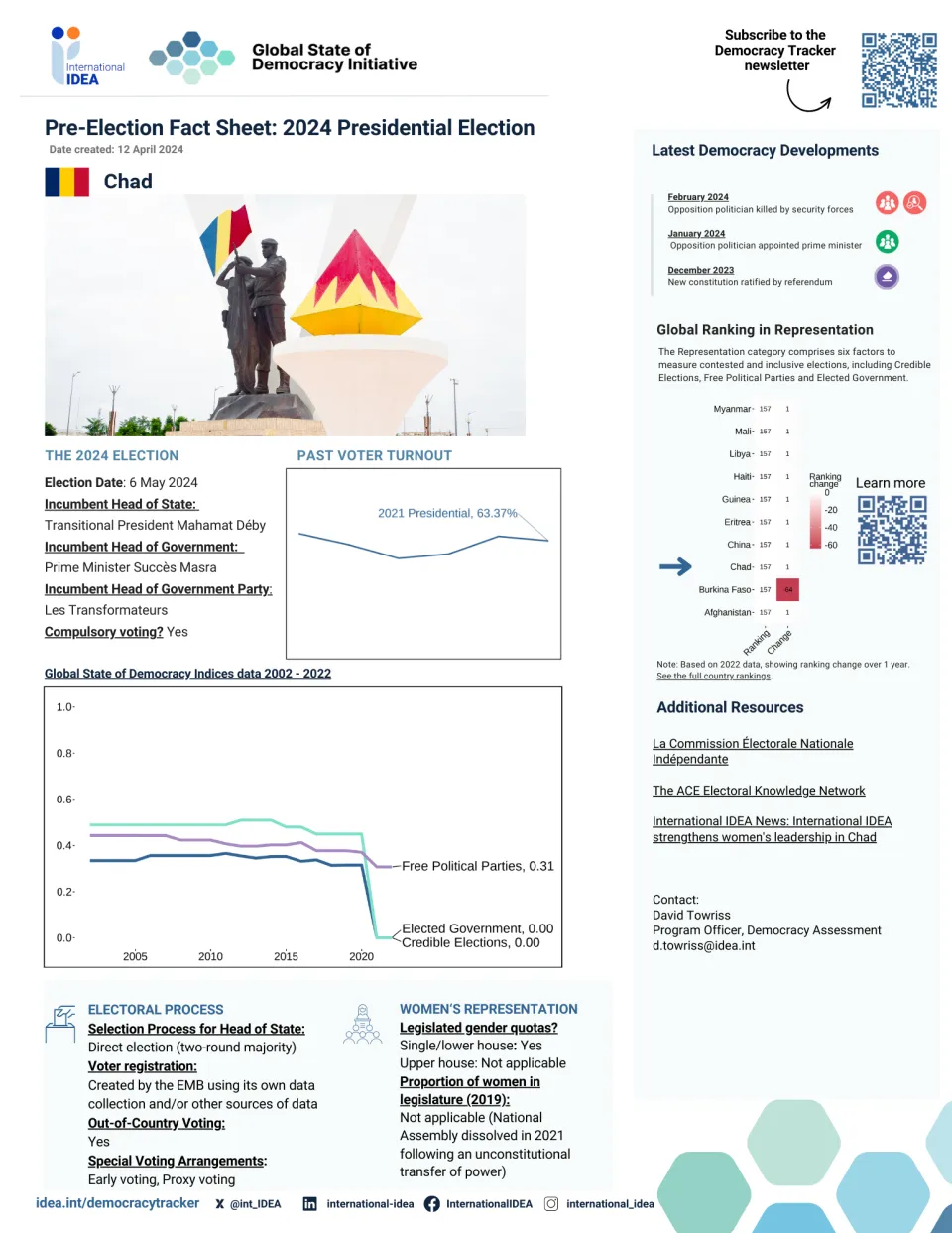

Chad is currently emerging from a political transition to civilian rule, after several years of an interim military government headed by the recently elected President, Mahamat Déby, and installed following the death of his father in 2021. While during the early stages of the transition Mahamat Déby signalled an openness to democratic reform, subsequent developments have reinforced authoritarian patterns. Under the recently ratified constitution, political power remains highly centralised and the 2024-2025 transitional elections were marred by political violence, media restrictions, and allegations of fraud.

Religious, ethnic and regional identities are highly salient in Chad where, since the late 1970s, the political elite have come from the Arab Muslim north, fuelling resentment within communities in the Christian and animist south, which demand greater representation. There is also broader discontentment over the political, economic, and military dominance of the Déby family’s Zaghawa ethnic group during their rule. Additionally, these identities have been an important driver of the deadly intercommunal violence between sedentary farmers and cattle herders competing over scarce resources.

Chad is among the world’s bottom 25 per cent of countries with regard to Gender Equality, despite constitutional protections. It has among the world’s highest rates of child marriage, and female genital mutilation is widely practiced. Same-sex activity is criminalised, and the wider LGBTQIA+ community are severely stigmatized.

Looking ahead, Rights will be an important area to monitor in light of the growing restrictions on political space, including the detention of political opponents and journalists. Rights and Rule of Law should be similarly monitored in the near-term for the potentially destabilizing impacts of the war in neighbouring Sudan. The resource strain emanating from the influx of Sudanese refugees, for example, has exacerbated intercommunal tensions in the border regions.

Last updated: July 2025

https://www.idea.int/democracytracker/

October 2025

President Déby promulgates constitutional revisions entrenching his rule

On 8 October, President Mahamat Déby promulgated constitutional reforms that analysts say will entrench his rule. While presented by the government as ‘technical’ revisions, thereby avoiding the need to hold a confirmatory referendum, the reforms significantly alter the 2023 constitution. They abolish presidential term limits and (after the next election) extend presidential terms from five to seven years, changes that are likely to strengthen President Déby’s incumbency advantage, further undermining the competitiveness of presidential elections and consolidating Chad’s dynastic system (President Deby was preceded in office by his father, who ruled as president for more than 30 years). Another notable change is the reversal of the prohibition on the president holding office in a political party. This legalises Déby’s assumption of the leadership of the ruling Patriotic Salvation Movement (Mouvement Patriotique du Salut, MPS) in January 2025, thereby formally eroding the separation of party and state.

Sources: Constitution Net, Human Rights Watch, International Federation for Human Rights

September 2025

Chad strips two government critics of citizenship

On 17 September, Chad’s government published a decree revoking the citizenship of two prominent government critics, journalist Charfadine Galmaye Saleh and human rights activist Nguebla Makaïla. Saleh is editor-in-chief of TchadOne, one of Chad’s most influential online media outlets and Makaïla is a blogger who previously served as human rights advisor to President Mahamat Idriss Déby. Both live in exile in France. The decree, which was issued by the Ministry of Territorial Administration, accused them of having ‘collaborat[ed] with foreign powers’ and engaged in ‘activities incompatible with the status of a Chadian citizen.’ However, the citizenship revocations have been interpreted by rights groups as a means of silencing dissent in Chad, and they have also alleged that the government’s actions breached both national and international law.

Sources: Ministère de l'Administration du Territoire et de la Décentralisation-Tchad, World Organisation Against Torture, Human Rights Watch, Radio France Internationale

August 2025

Opposition leader Succès Masra receives 20-year prison sentence

On 9 August, the High Court of N’Djamena sentenced opposition leader and former Prime Minister Succès Masra to 20 years in prison, following his conviction for complicity in murder and disseminating hateful and xenophobic messages in proceedings widely perceived to be politically motivated. The convictions relate to deadly intercommunal violence that took place in southwest Chad in May 2025, which prosecutors alleged was triggered by an audio recording of Masra calling for farmers to arm themselves against herder communities. Masra, who denies all the charges against him, says the recording was from 2023 and that he had simply called on the farmers to form self-defence groups. His lawyers criticised the state for a lack of evidence against their client and commentators also raised due process concerns. Masra was tried alongside the perpetrators of the violence and in addition to custodial sentences, they were collectively fined CFA francs 1 billion (approximately US$1.8 million).

Sources: Jeune Afrique, Deutsche Welle, The Conversation, Human Rights Watch, International IDEA

May 2025

Chad detains opposition leader Succès Masra

On 16 May, Chadian authorities arrested the leader of the opposition Transformers (Les Transformateurs) party and former Prime Minister, Succès Masra, as part of an investigation into recent intercommunal violence between farming and herding communities in the southwest of the country. Prosecutors alleged that the violence was triggered by an audio recording of Masra urging farmers in the affected village to arm themselves and he was charged with incitement to hatred and revolt, complicity in murder and the desecration of graves. On 21 May, he was placed in pre-trial detention. Masra denies the charges against him, saying the recording is two years old and that in it he had simply called on the farmers to form self-defence groups. The opposition leader is a fierce critic of President Mahamat Idriss Déby Itno and his lawyers and party allege the prosecution is politically motivated. His arrest followed a resumption of his opposition activities in the country’s capital, N'Djamena.

Sources: Reuters, International Crisis Group, Jeune Afrique (1), Jeune Afrique (2)

See all event reports for this country

Global ranking per category of democratic performance in 2024

Basic Information

Human Rights Treaties

Performance by category over the last 6 months

Election factsheets

Global State of Democracy Indices

Hover over the trend lines to see the exact data points across the years

Factors of Democratic Performance Over Time

Use the slider below to see how democratic performance has changed over time