South Africa

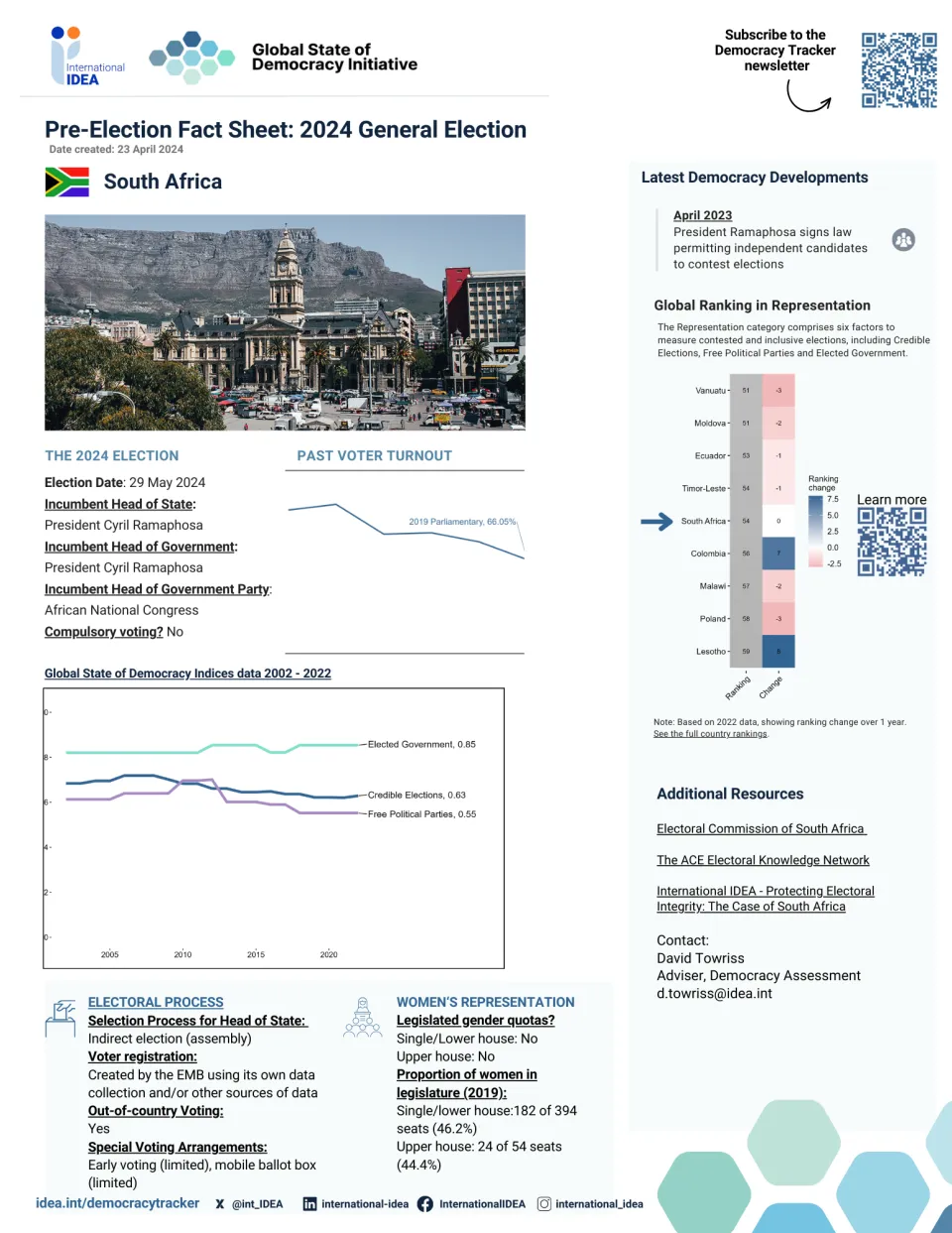

South Africa performs in the mid-range across three categories of the Global State of Democracy (GSoD) framework (Rights, Rule of Law and Participation) and is high-performing in Representation. Compared to 2019, South Africa has experienced significant advances in Credible Elections and Judicial Independence. Its economy is one of the continent’s largest and most industrialised, and key sectors include mining, transport, energy, manufacturing, tourism and agriculture. For over a decade, however, economic growth has been weak, entrenching high levels of unemployment and poverty.

South African society has been deeply marked by over 300 years of racial discrimination, imposed first during Dutch and then British colonial rule, and later formalised under Apartheid. Through social and labour controls, the Apartheid system ensured that South Africans of different races were spatially segregated and set on highly unequal socio-economic paths. South Africa’s post-Apartheid governments have had limited success in reversing the effects of this social engineering. While affirmative action policies have helped create an emergent black middle class, South Africa’s society is one of the world’s most unequal, and the inequality remains racialised. Its chronically poor (nearly half of the population) are almost exclusively black and coloured, while its small white minority comprises a disproportionately large part of the middle class and elite. The persistence of racial and economic inequalities, alongside rampant corruption, widespread violent crime (including political assassinations) and service delivery failures, have led to declining trust in democratic institutions.

South Africa is a mid-performer on the GSoD’s Gender Equality measure but inequalities, in combination with widespread sexism, have helped sustain one of the highest rates of gender-based violence in the world. Government legislative action on the issue means the country has a robust legal framework governing discrimination and violence, but its response has been criticised for a lack of resources. South Africa is a leader in LGBTQIA+ rights, enshrining the world’s first constitutional prohibition of sexual orientation discrimination and is the only African country to legalize same-sex marriage. However, LGBTQIA+ persons continue to face stigma, violence and high rates of HIV.

South Africa has 12 official languages and four racial groups and ethnolinguistic identities constitute an important political cleavage, particularly at the sub-national level. Salient too, is the nativist nationalism that has long had currency in South African politics and society and increasingly threatens the ‘Rainbow Nation’ cosmopolitanism introduced by Nelson Mandela’s administration. It has been visible in anti-immigrant political rhetoric and in the xenophobic violence that has marked periods of the country’s recent history.

In meeting these and other challenges, South Africa benefits from a vibrant civil society, which has succeeded in using the country’s acclaimed constitution to secure pioneering human rights and democratic protections. Indeed, the South African Constitutional Court’s jurisprudence is internationally respected, particularly on questions of socio-economic rights.

Since the 2024 general election, in which the long-governing African National Congress lost its parliamentary majority, South Africa has been governed by a coalition government. Looking ahead, it will be important to monitor the stability of the coalition and its impact on the country’s democratic performance in multiple areas, including Basic Welfare, Political Equality, Absence of Corruption and Effective Parliament. Attention should paid, in particular, to Judicial Independence, following steps announced by President Ramaphosa to strengthen the institutional, administrative and financial independence of the courts.

Last updated: July 2025

https://www.idea.int/democracytracker/

October 2025

Constitutional court rules parents equally entitled to parental leave

On 3 October, the Constitutional Court ruled that all parents are equally entitled to parental leave granted under South African law, declaring that current provisions granting birth mothers four months leave and ten days to other categories of parents, were unconstitutional. The other categories of parent addressed were fathers, adoptive parents and parents of children born to surrogates. The Court found that by treating parents unequally in this way, the law unfairly burdened birth mothers with childcare duties, while marginalising the role of the other categories of parent and depriving parents of the choice of how to structure their child rearing responsibilities. The judgement allows parliament 36 months to remedy the law and, in the meantime, amends the current provisions to allow the four months and ten days leave to be shared between parents.

Sources: Constitutional Court of South Africa, Commission for Gender Equality, Sonke Gender Justice

Inquest finds Chief Albert Luthuli was murdered by apartheid police

On 30 October, the KwaZulu-Natal High Court ruled in its inquest into the 1967 death of Chief Albert Luthuli, concluding that the former president of the African National Congress (ANC) had been murdered by the apartheid police. Luthuli led the ANC from 1957 until his death, spearheading the struggle against apartheid and in 1961 was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize. The Court found that he had been beaten to death by members of the Apartheid Security Branch, in collaboration with employees of the South African Railway Company, and it set aside the ruling of a discredited 1967 inquest that Luthuli died after being hit by a goods train. Prosecutions are unlikely to follow, as those responsible for Luthuli’s death have either died or cannot be traced. However, the judge recommended that prosecutors investigate the kidnapping or enforced disappearance of witnesses in the case. The inquest is one of several reinvestigating the deaths of anti-apartheid leaders and activists.

Sources: Eye Witness News, Daily Maverick, Parliament of the Republic of South Africa

September 2025

Inquest into the death of anti-apartheid leader Stephen Biko reopened

On 12 September, in the High Court, South African prosecutors reopened an inquest into the death of prominent anti-apartheid leader Stephen Biko, who died in 1977 after allegedly being tortured by five members of the apartheid state’s police force. A founder of the Black Conscious Movement that aimed to empower and mobilise black South Africans, Biko’s death had a profound impact on the country. In 1977, a widely criticised inquest determined that he had died of an extensive brain injury, but did not assign criminal responsibility, accepting the testimony of the police officers that the injury had been self-inflicted. Despite admitting to the Truth and Reconciliation Commission in 1997 that they had fabricated their statements, the officers (two of whom are still alive) were not prosecuted. As well as revisiting the cause of Biko’s death and potentially paving the way for prosecutions, the inquest aims to ‘provide closure to the Biko family and society at large.’

Sources: National Prosecuting Authority, Department of Justice and Constitutional Development, Daily Maverick

August 2025

Anti-immigrant campaign blocks suspected undocumented migrants from accessing healthcare

Investigations by NGO Médecins Sans Frontières (MSF) and the Daily Maverick newspaper revealed that an ongoing campaign by anti-immigrant groups to block undocumented migrants from accessing public health facilities has affected at least 53 facilities across four provinces. The campaign, which began in June and has been led by the controversial vigilante group, Operation Dudula (meaning ‘to force out’ in Zulu), has involved activists barring foreign nationals from entering hospitals and clinics where they have been unable to produce identification. According to MSF, the affected patients included pregnant women and people living with high-risk conditions such as HIV and diabetes, some of whom had not received medical attention for weeks and had run out of medication. Operation Dudula accuses the government of failing to manage immigration, but their campaign has been widely condemned, including by government ministers, parliamentarians and civil society.

Sources: Daily Maverick, Médecins Sans Frontières, Independent Online

May 2025

Inquiry established into delays in investigation and prosecution of TRC cases

In May, President Cyril Ramaphosa established a judicial commission of inquiry to determine whether attempts were made to prevent the investigation and prosecution of apartheid era crimes identified by South Africa’s Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC). According to President Ramaphosa, since the TRC published its final report in 2002, 158 of the more than 300 cases referred for prosecution by the commission remain under investigation and only one has resulted in a conviction. These delays have fuelled long-standing allegations of improper influence in the cases. The establishment of the inquiry is an outcome of a lawsuit brought by 25 families and survivors of apartheid-era crimes. The inquiry is expected to complete its work by the end of November 2025 and submit its report within 60 days of the completion date.

Sources: The Presidency, Republic of South Africa, South Africa Human Rights Commission, News 24

See all event reports for this country

Global ranking per category of democratic performance in 2024

Basic Information

Human Rights Treaties

Performance by category over the last 6 months

Blogs

Election factsheets

Global State of Democracy Indices

Hover over the trend lines to see the exact data points across the years

Factors of Democratic Performance Over Time

Use the slider below to see how democratic performance has changed over time