Uruguay

Uruguay performs in the high range across three categories of the Global State of Democracy framework (Rights, Representation and Participation) and in the mid-range for Rule of Law. It scores among the world's top 25 per cent of countries in most factors. Over the last five years, it has experienced significant declines in several factors of Rights and Rule of Law. Uruguay is a high-income country with an economy driven by agriculture, manufacturing and services.

Other than a period of military dictatorship between 1973 and 1985, the country has the longest democratic history in South America. Today, politics are stable and dominated by two ideological camps: a center-right coalition comprising five parties, including the Partido Nacional and Partido Colorado and a center-left coalition called Frente Amplio. The country is relatively cohesive, with no religious, regional or ethnic oonflicts. Most of the population is of European descent or mixed. Minority groups include Afro-descendants, a Jewish community and Indigenous groups.

In the late 1990s and early 2000s, Uruguay went through a severe economic crisis, prompting structural reforms, such as banking system reorganization, improvements of financial regulation and accountability, and debt restructuring. Despite significant economic strengthening, nearly ten per cent of the population lives below the poverty line, which particularly affects children, adolescents, women and Afro-descendants.

Uruguay’s politics are currently shaped by debates over rising homicide rates, linked to increased drug trafficking. To address this, the government passed the Ley de Urgente Consideración (LUC) in 2020, expanding police power, introducing harsher sentencing, restricting protests and creating a Secretariat of State Strategic Intelligence—criticised given the country’s history of dictatorship. Despite concerns about civil liberties, a 2022 referendum on repealing the LUC narrowly resulted in its key provisions being upheld. Since then, human rights organizations have denounced worsening prison conditions, including peaking incarceration rates—the highest per capita in South America.

In recent years, the political landscape has been marked by corruption scandals, and the poor handling of a 2023 severe water crisis—ongoing since 2020— that triggered investigations, resignations, and widespread water shortages, severely affecting agriculture and eroding public trust in the ruling coalition. A media law has received significant criticism from international and local organizations for its potential harm to freedom of expression and possible increases in media ownership concentration. In 2024, general elections brought a new administration whose agenda included strengthened social inclusion and environmental policies.

Uruguay has strong laws to protect women and the LGTBQIA+ community. Homosexuality was decriminalized over two decades ago, followed by marriage and adoption rights for same-sex couples. Despite an advanced legal framework for women’s rights—including protections against violence and sexual and reproductive rights—gender-based violence remains widespread and women are disproportionally affected by poverty and alarming rates of incarceration. The latter is largely due to recent policies that harshly prosecute micro-trafficking—an activity primarily carried out by vulnerable women.

In the years ahead, it will be important to follow how the country controls its high homicide rates and the effects on Personal Integrity and Security, as well as how security policies may impact Gender Equality in light of rising female incarceration rates. Lastly, it will be important to watch how the new government addresses ongoing inequality—particularly affecting minors and other vulnerable groups—and its impacts on Social Group and Economic Equality.

Updated June 2025

https://www.idea.int/democracytracker/

December 2025

Court issues landmark ruling for crimes committed during the dictatorship

On 22 December, the Fray Bentos Court in Uruguay sentenced nine retired military officers to prison terms ranging from 11 to 15 years for crimes committed during the 1973-1985 military dictatorship. They were convicted of serious human rights violations, including arbitrary detentions and systematic torture, with the case highlighting the torture and death of Dr. Vladimir Roslik, the dictatorship's last known victim. The court classified these acts as crimes against humanity and issued a formal apology on behalf of the state to the victims and their families. This ruling marks a pivotal step toward addressing historical injustices and reaffirming the state's commitment to truth, justice, and reparation.

Sources: Infobae, TeleSur, El Popular, Sitios de Memoria Uruguay

September 2025

Prosecutor targeted in assassination attempt linked to organized crime

On 28 September, two individuals entered Acting Attorney General Mónica Ferrero’s home, opened fire, and allegedly attempted to place explosives in her backyard in what was seen as an assassination attempt against the country’s top anti-narcotics prosecutor. The incident occurred while Ferrero and her family were at home under police protection and resulted in no injuries. Police believe the attackers were linked to an international crime group led by fugitive drug lord Sebastián Marset. The assault is thought to be retaliation for a recent anti-narcotics operation led by Ferrero, which seized over two tons of cocaine and led to several arrests. In addition to targeting Ferrero personally, officials claim the attack was also meant to send a warning to members of the judiciary involved in prosecuting organized crime. Assassination attempts are extremely rare in Uruguay, making this episode a major escalation and a serious warning sign of the increasing influence of organized crime in the country.

Sources: Insightcrime, Pagina 12, El Observador, El Pais, Infobae

October 2024

Yamandú Orsi is elected Uruguay’s next President

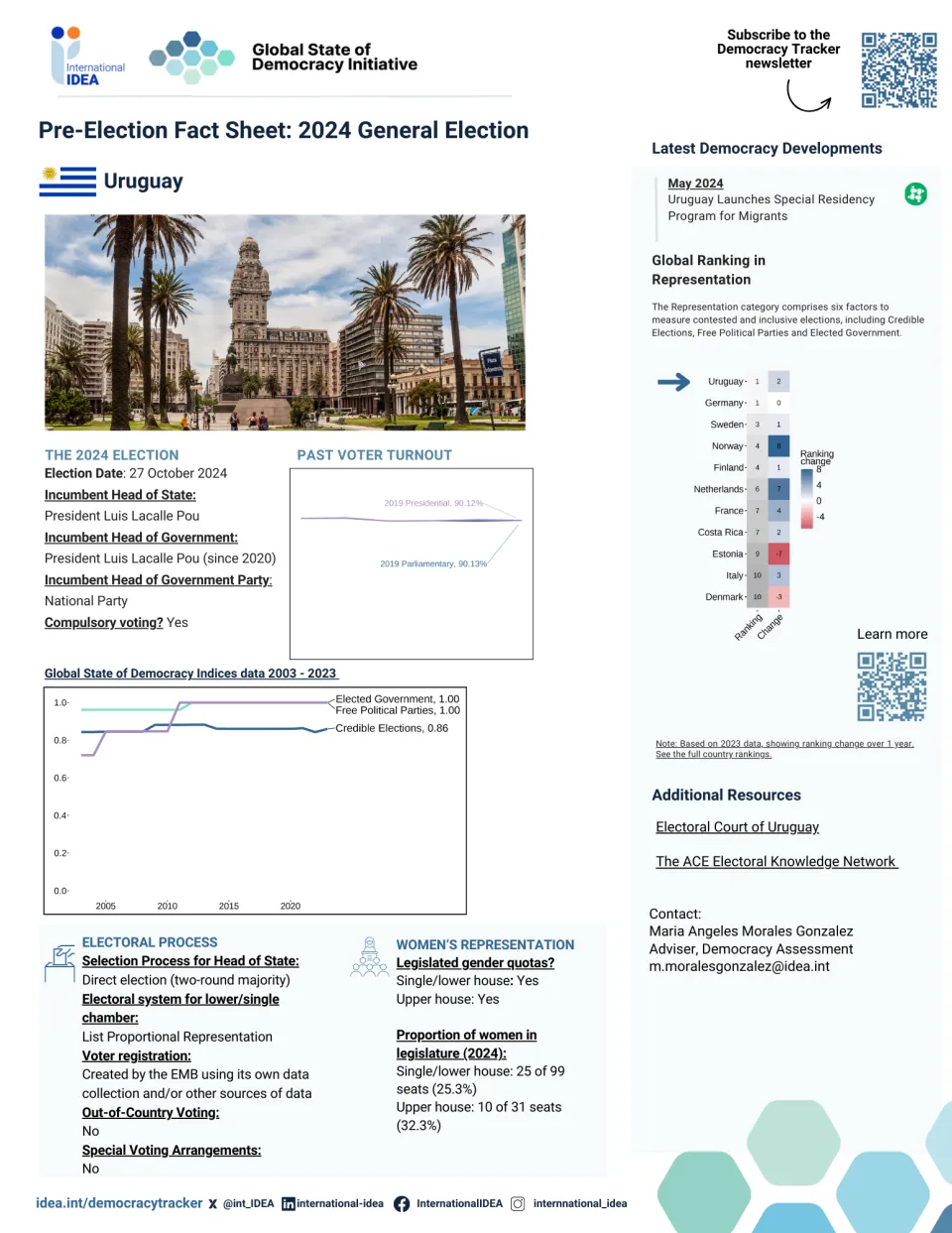

On 27 October, Uruguay held general elections. Voter turnout was 89.52 per cent, similar to the 90,13 per cent recorded in the last elections in 2019 (voting is compulsory). Uruguayans had the option to vote for one of 11 presidential tickets, all led by men. Yamandú Orsi from the Frente Amplio coalition and Álvaro Delgado from the National Party led the presidential race with 44 and 27 per cent of the vote, respectively. As neither reached the required 50 per cent, a run-off will take place on 24 November.

Voters also elected 30 members of the Senate, 99 members of the House of Representatives, and members of municipal electoral boards. The Frente Amplio coalition obtained a majority in the Senate, while no party secured a majority in the lower chamber. Preliminary calculations indicate that 27.9 per cent of legislative seats will be held by women, an increase from the 20 per cent elected in the 2020 elections.

Additionally, two plebiscites—one on pension reform and the other on restoring police authority to conduct nighttime raids—did not pass, as both fell short of the required 50 per cent voter support.

Update: A run-off was held on 24 November. The Frente Amplio coalition’s Yamandú Orsi became the country’s new president, with 49.8 per cent of the vote. Álvaro Delgado garnered 45.87 per cent, and voter turnout was 89.4 per cent.

Sources: International IDEA, Montevideo Portal, Corte Electoral Uruguay (1), El Pais Uruguay, AP News, Corte Electoral Uruguay (2), CNN

May 2024

Uruguay Launches Special Residency Program for Migrants

An executive decree launched in Uruguay creates a special residency program based on family, or educational ties, which will also facilitate integration. The special residency program applies only to migrants who have been in the country for more than 180 days at the time of the decree's issuance. It is therefore aimed at regularizing the status of people who are already in the country. It will benefit over 20,000 foreigners, mostly Cubans, caught in a "migratory limbo" who entered the country as asylum seekers but stayed in Uruguay without being able to acquire legal residence. Additionally, it provides a process to permanent residency and eventually citizenship. The program will also facilitate family reunification, which is not possible for individuals who have an undefined legal status. The United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees has praised the measure for recognizing migrants' humanitarian needs and strengthening pathways to stay legally in Uruguay. Migrants’ organizations support the measure, stating that it will help thousands stay legally in the country.

Sources: El País Uruguay, Infobae, El Pais, UNHCR, Uruguayan Ministry of Foreign Affairs

See all event reports for this country

Global ranking per category of democratic performance in 2024

Basic Information

Human Rights Treaties

Performance by category over the last 6 months

Election factsheets

Global State of Democracy Indices

Hover over the trend lines to see the exact data points across the years

Factors of Democratic Performance Over Time

Use the slider below to see how democratic performance has changed over time