Mozambique

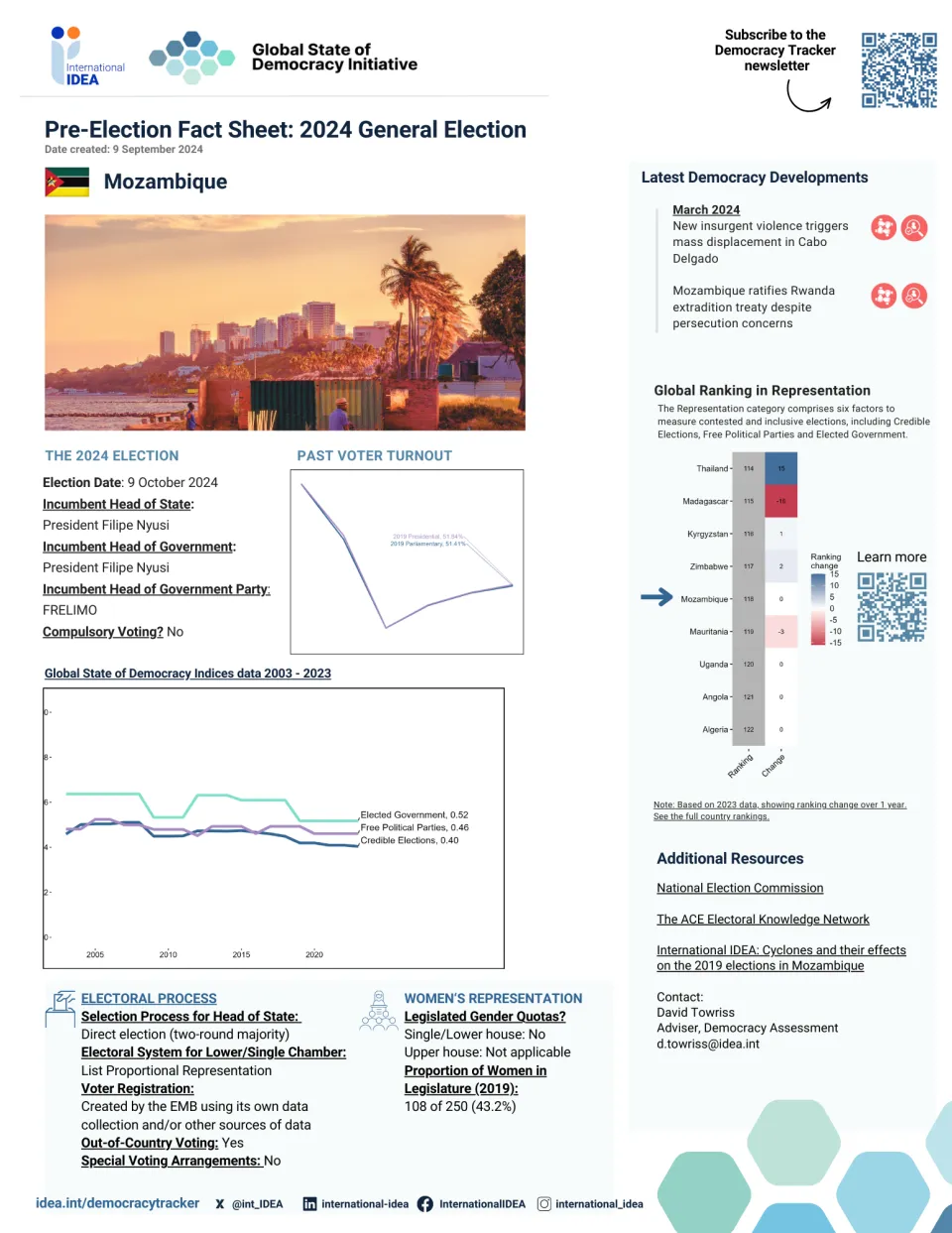

Mozambique performs at the low-range in three categories of the Global State of Democracy (GSoD) framework (Representation, Rights and the Rule of Law) and at the mid-range in Participation. Compared to 2019, it has suffered declines in Credible Elections, Free Political Parties, Civil Liberties and Absence of Corruption. Mozambique has a diverse economy, with key sectors including agriculture, mining, and energy. However, its economic development has been hindered by conflict, natural disasters and corruption and it remains one of the poorest countries in the world.

Once part of a trade network spanning the African continent and Indian ocean, present-day Mozambique was colonized by the Portuguese, who sought to control the trade. Colonization began in the sixteenth century and culminated in the establishment of a settler administration, whose exploitative rule left Mozambique with a distorted economy, weak administrative capacity and arbitrary borders. After a 16-year-long armed struggle led by the Marxist Mozambique Liberation Front (FRELIMO), the country gained its independence in 1975, with power handed to FRELIMO as the ruling party. Since then, it has governed Mozambique continuously; initially as a one-party state, before introducing a formally multi-party system and holding Mozambique’s first elections in 1994. However, politics and the economy have continued to be controlled by the ruling party and allied elites.

Although Mozambique’s constitutional arrangements provide for a formal separation of powers between the three branches of government, neither the judiciary nor legislature effectively check the powerful presidency, primarily because of the blurred lines between the ruling party and the state. Consequently, democratic space has become increasingly restricted as FRELIMO has responded to popular discontent by repressing critical voices in civil society, opposition parties and the press, and controlling democratic processes, most notably elections. The contested 2024 general election triggered widespread, deadly violence between protesters and the security agencies. The protests reflected a broad set of governance concerns, including police brutality, poverty, youth unemployment and corruption, which is a major problem, exemplified by the Hidden Debt scandal.

Mozambique’s socio-political landscape has also been profoundly impacted by the civil war, fought by FRELIMO and the anti-communist Mozambican National Resistance (RENAMO), now an opposition party. FRELIMO-RENAMO tensions were later reignited by a six-year low-intensity guerrilla campaign waged by RENAMO militants between 2013 and 2018. In recent years, an Islamic insurgency has grown in the northern province of Cabo Delgado. These conflicts have been fuelled by resentments over long-standing regional socio-economic inequalities, which divide the relatively prosperous south from the more populous north.

Mozambique is a mid-performer on the GSoD’s Gender Equality measure. Despite legal protections, the marginalization of women continues, with gender-based violence widespread and persistent gaps in representation in leadership in both the public and private sectors, access to education and employment. Same-sex relations are legal, but LGBTQIA+ persons generally lack legal protections and face stigma.

Looking ahead, it will be important to monitor the government’s approach to the post-election instability and popular demands for governance reform. Relevant in this regard are the discussions between President Daniel Chapo and former presidential candidate Venâncio Mondlane, the national dialogue between the government, political parties and civil society, as well as the prosecution of protesters and the policing of future protests. The impact of these developments may be felt across the GSoD framework, but in the short-term Personal Integrity and Security, Civil Liberties and Civil Society are areas to watch.

Last updated: July 2025

https://www.idea.int/democracytracker/

August 2025

Insurgent attacks cause mass displacement in northern Mozambique

The UN’s International Organisation for Migration reported on 5 August that in the preceding two weeks nearly 60,000 people had been displaced from Mozambique's northern Cabo Delgado province, as a result of escalating attacks from insurgents operating in the area. Since January 2025, more than 95,000 people are estimated to have fled the ongoing insurgency in Cabo Delgado, and access to food, shelter, medical care and other basic necessities has become increasingly fragile for displaced persons and host communities. This has been exacerbated by the scaling back of humanitarian assistance in response to international aid cuts.

Update: Approximately 100,000 people were displaced from northern Mozambique in the second half of November, as attacks by insurgents intensified and spread beyond Cabo Delgado Province, where the insurgency has been concentrated. According to the IOM, it is the fourth major influx of internally displaced people Northern Mozambique has faced in recent months.

Sources: Al Jazeera, Club of Mozambique, United Nations (1), Médecins Sans Frontières, United Nations (2), Africa News

June 2025

Child abductions surge in Cabo Delgado province

In June, the United Nations and Human Rights Watch (HRW) reported a significant rise in the number of children abducted by insurgents in Mozambique’s conflict-affected Cabo Delgado province. A local monitor told HRW that ‘in recent days, 120 or more children have been abducted’. In 2024, the UN recorded a total of 468 child abductions in Cabo Delgado. Most abductees are forced into labour, marriages and combat by the militants, who have been fighting an insurgency in the province since 2017.

Sources: United Nations (1), Human Rights Watch, United Nations (2)

March 2025

Mondlane and President Chapo commit to ending post-election violence

On 24 March, former presidential candidate Venâncio Mondlane announced that he had met with President Daniel Chapo and that they had committed to end the ongoing post-election violence that, as of the end of February, had killed over 350 people. Mondlane, who disputes the results of the October 2024 general elections and leads the protest movement that emerged in its wake, said they had also agreed that the state would provide medical support to victims of the violence, compensate families of those killed and grant amnesty to arrested protesters. Further discussions between the two men are expected. The talks may signal a change of approach from the government, which on 5 March had excluded Mondlane from an agreement it signed with eight opposition parties, aimed at facilitating a national dialogue. So far, the State has taken a hard line against protesters, launching hundreds of criminal prosecutions and continuing to employ repressive tactics to police demonstrations.

Update: Political tensions were raised in Mozambique when on 22 July Venâncio Mondlane was charged with five offences relating to the post-election violence, including inciting terrorism, which carries a maximum 30-year prison sentence.

Sources: ISS Africa, Plataforma Eleitoral Decide, Club of Mozambique (1), Club of Mozambique (2), Club of Mozambique (3), Deutsche Welle (1), Deutsche Welle (2), International Crisis Group

December 2024

Violence continues to escalate as court confirms FRELIMO election victory

Violence in Mozambique continued to escalate during December, as the Constitutional Council confirmed the victory of the governing FRELIMO party in October’s disputed presidential and parliamentary elections. The ruling, delivered on 23 December, was rejected by all opposition parties and candidates, and the final results sparked fresh clashes between protesters and the police. In the week following the ruling, at least 176 people were killed, including protesters, children and police officers. In addition to spiralling police violence (reported to include summary executions), December also saw some protesters increase their looting and attacks on property and the security forces, as well as shut down key economic infrastructure, such as main roads, mines and power stations. By the end of the month, the UN Refugee Agency (UNHCR) estimated that at least 3,000 people had fled the country to Malawi and Eswatini.

Sources: Conselho Constitucional, British Broadcasting Corporation, Plataforma Eleitoral DECIDE, Africa Confidential, Le Monde, News 24, United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees

See all event reports for this country

Global ranking per category of democratic performance in 2024

Basic Information

Human Rights Treaties

Performance by category over the last 6 months

Election factsheets

Global State of Democracy Indices

Hover over the trend lines to see the exact data points across the years

Factors of Democratic Performance Over Time

Use the slider below to see how democratic performance has changed over time