The Global State of Democracy 2025

Democracy on the Move

When I wrote in The Economist at the start of 2024 about the challenges for democracy from mounting global uncertainty, I did not know the extent to which this would bear out over the year. In the following months, political developments in the United States highlighted a trend of democratic slippage in new forms and places, while conflict and insecurity shifted policy and funding priorities in ways that put democracy—and democracy support—into ever greater jeopardy. Today, the state and fate of democracy in the world is perhaps more uncertain than it has been in our lifetimes.

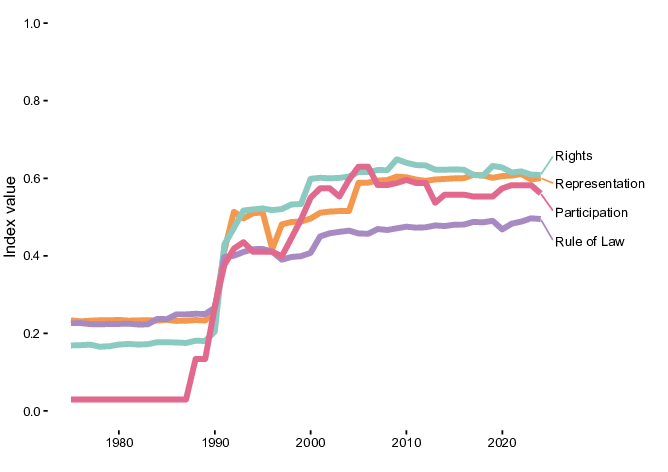

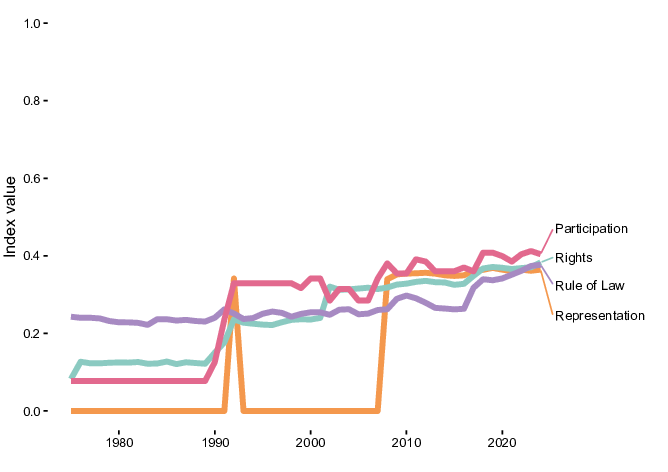

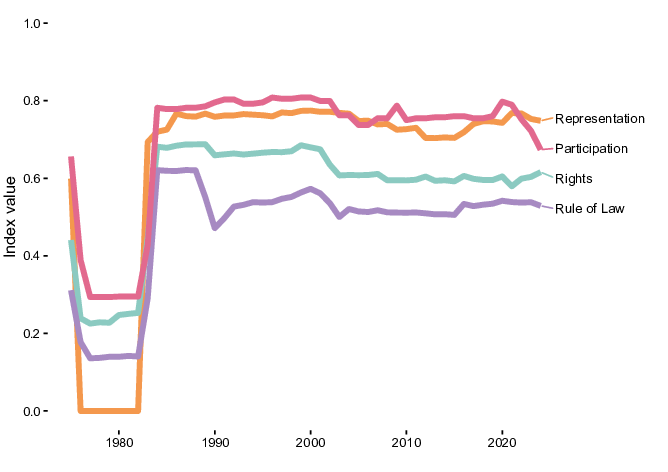

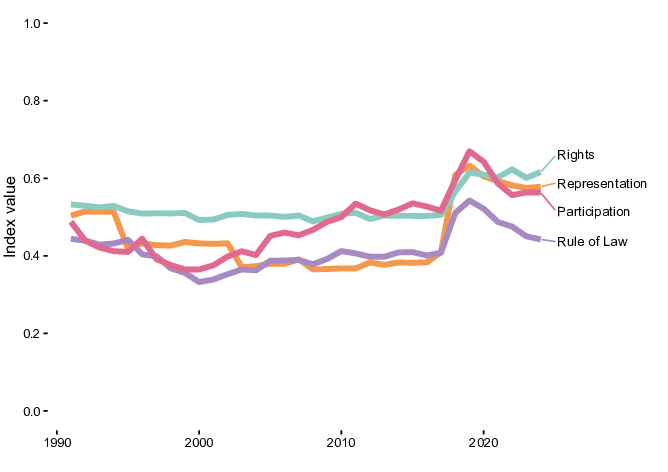

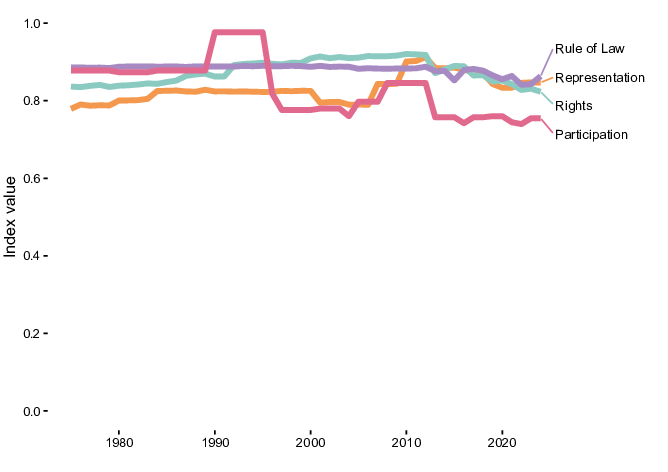

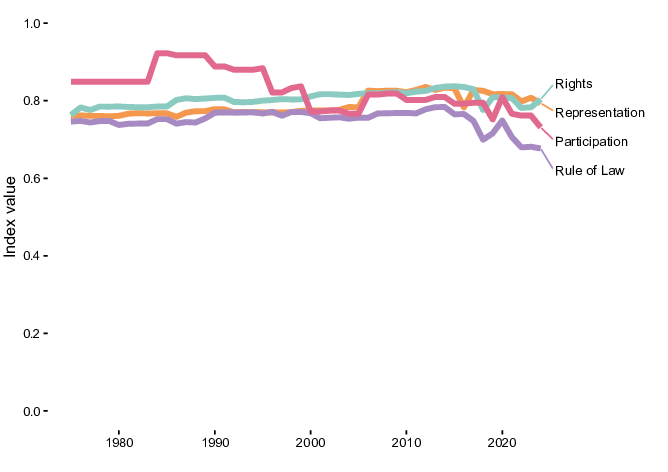

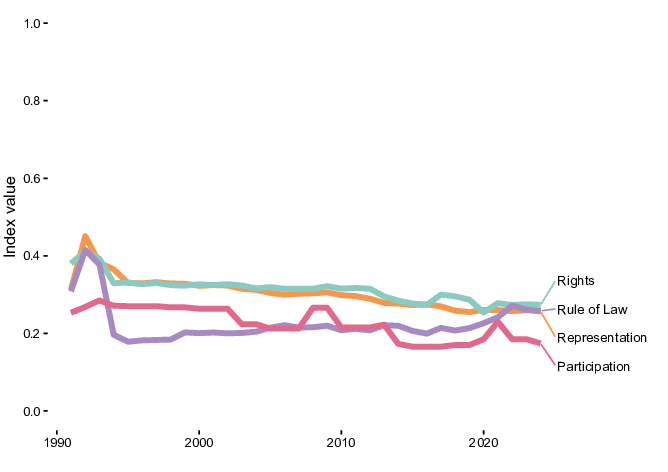

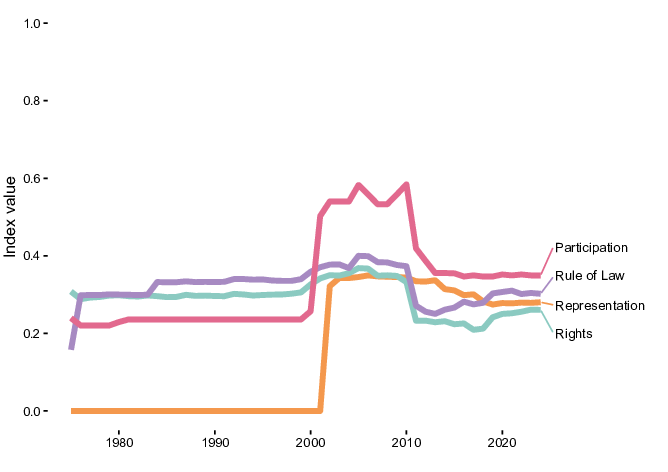

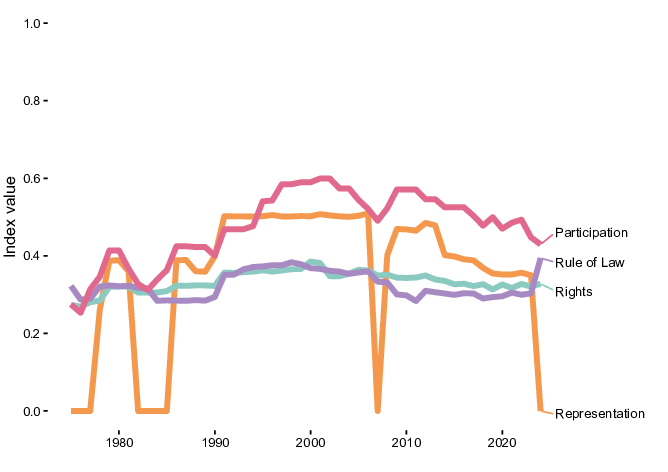

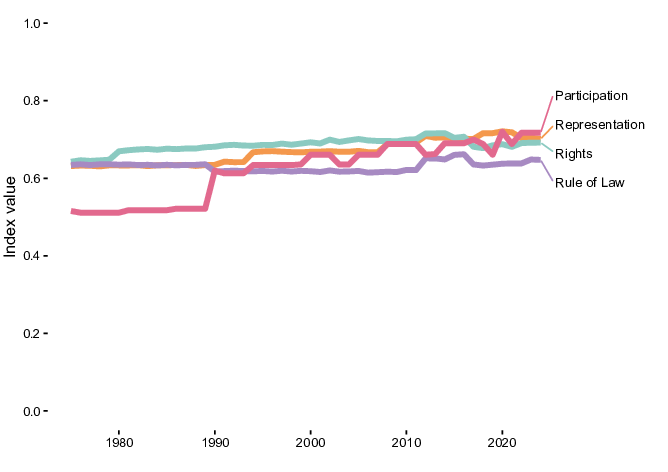

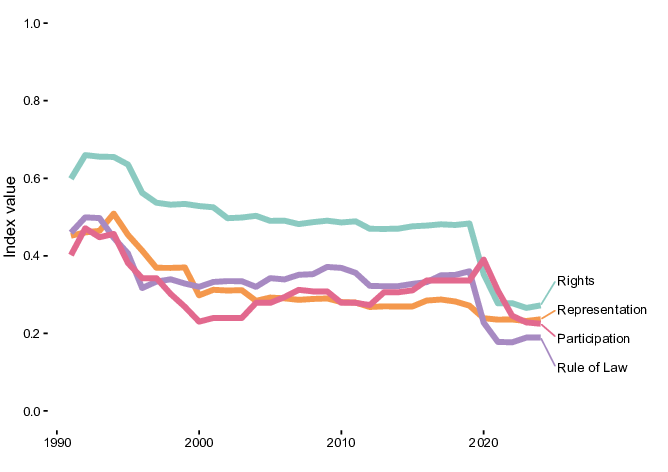

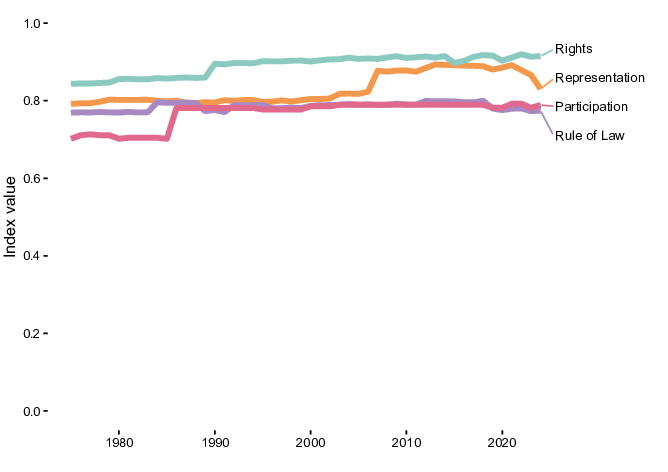

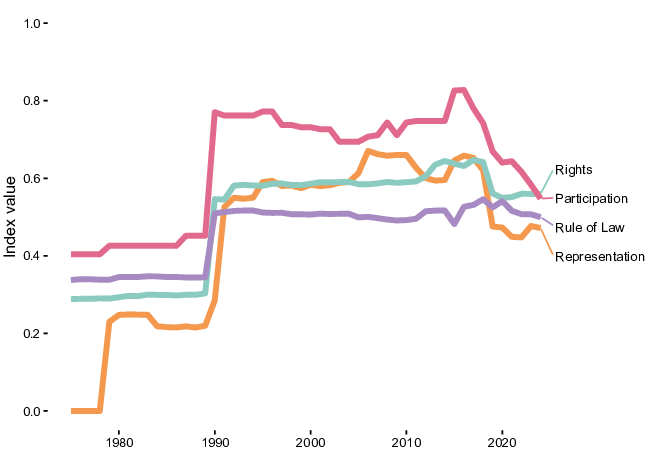

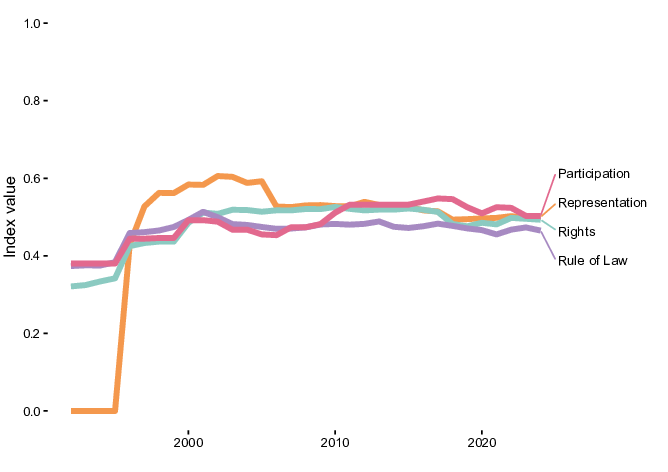

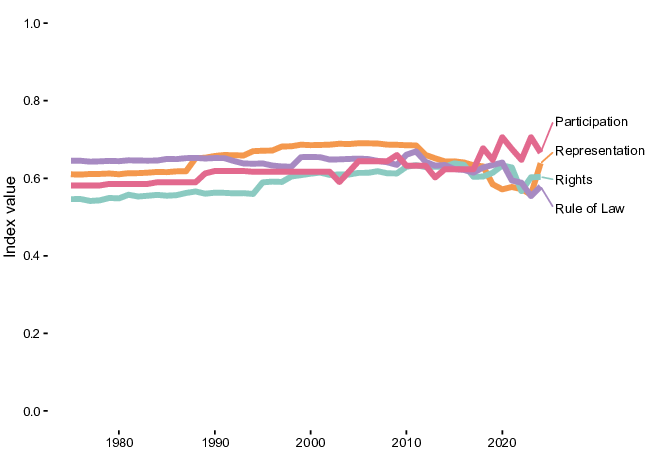

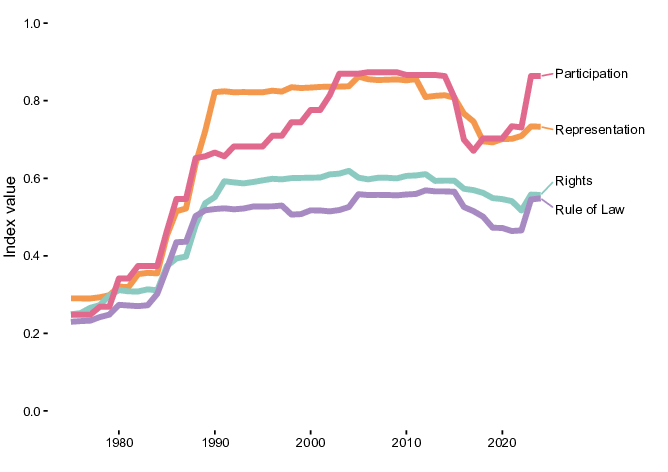

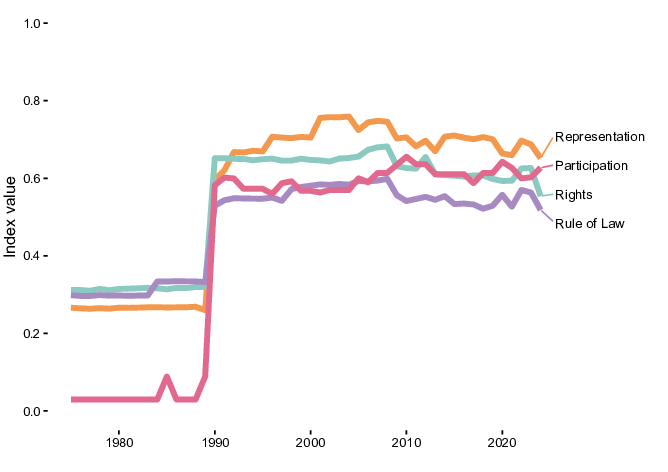

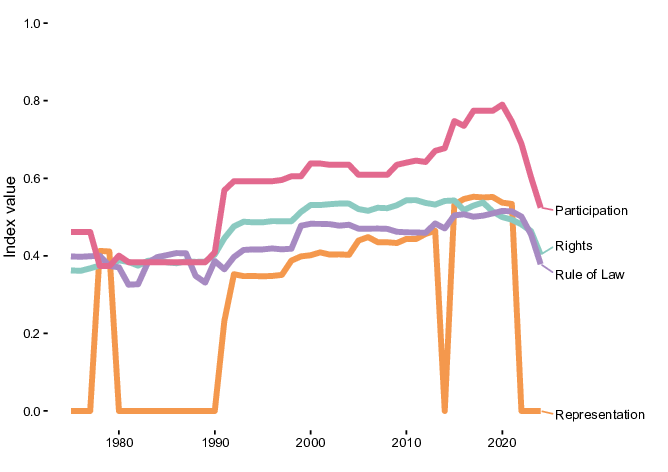

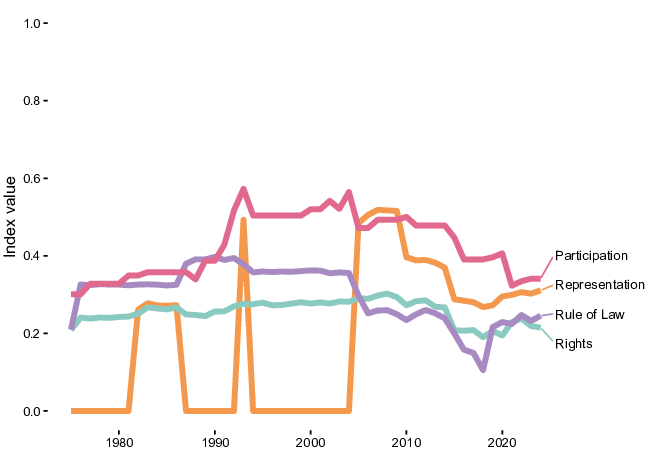

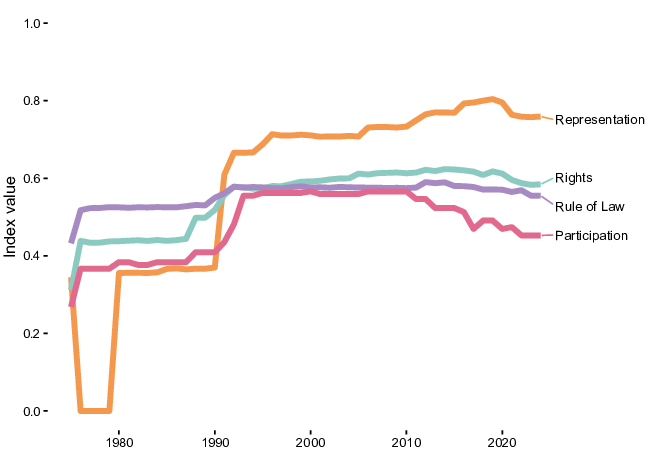

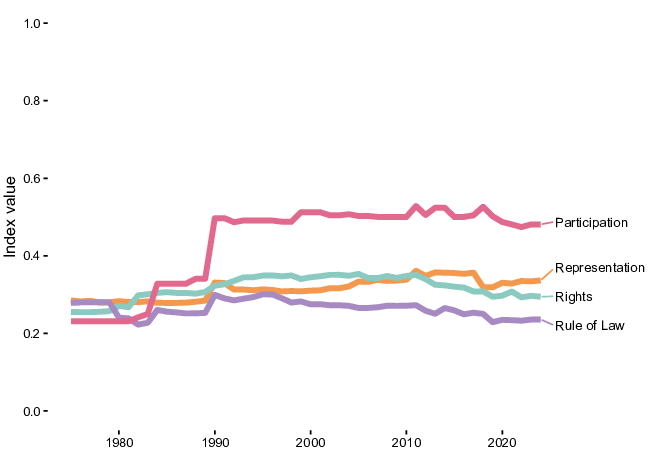

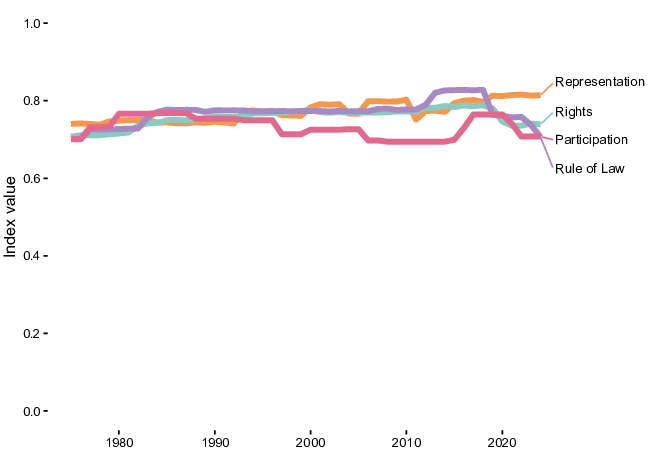

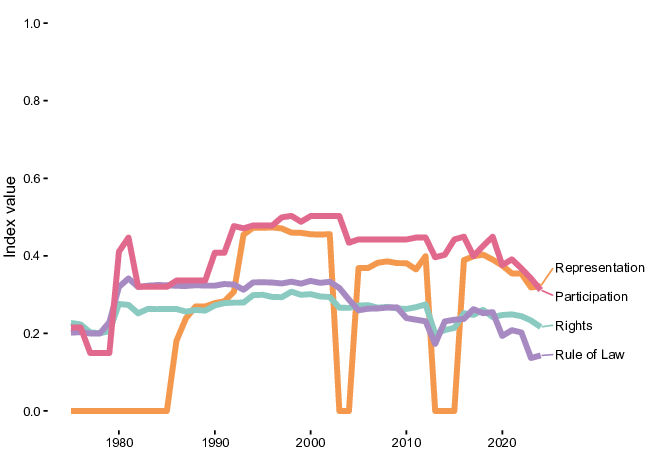

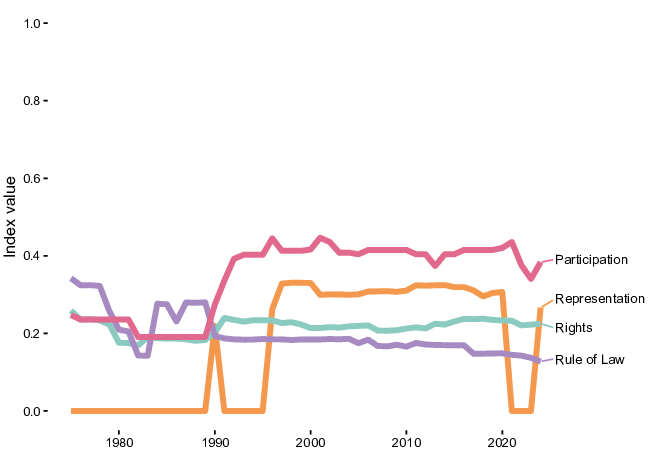

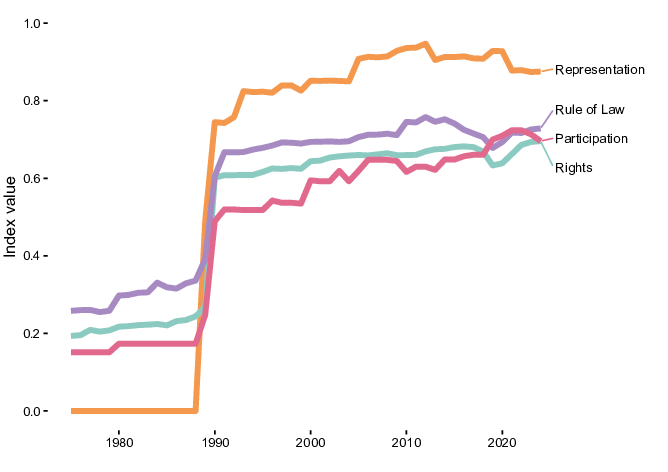

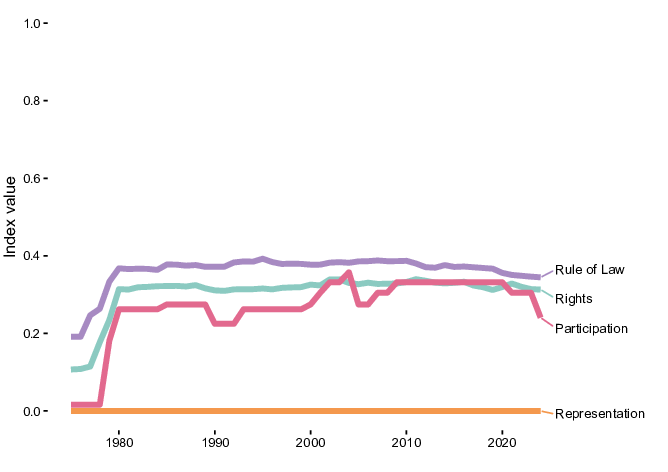

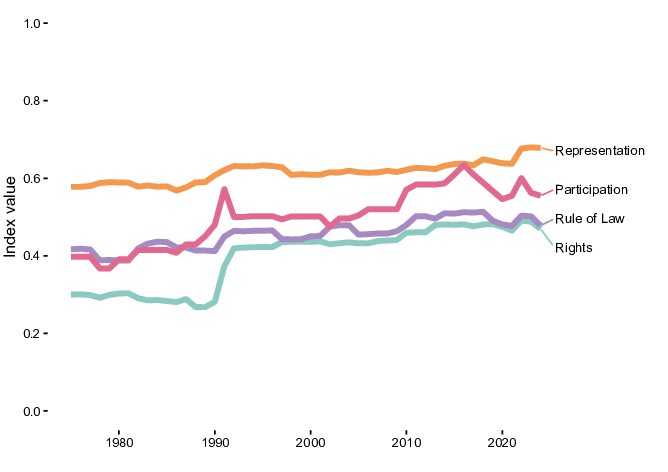

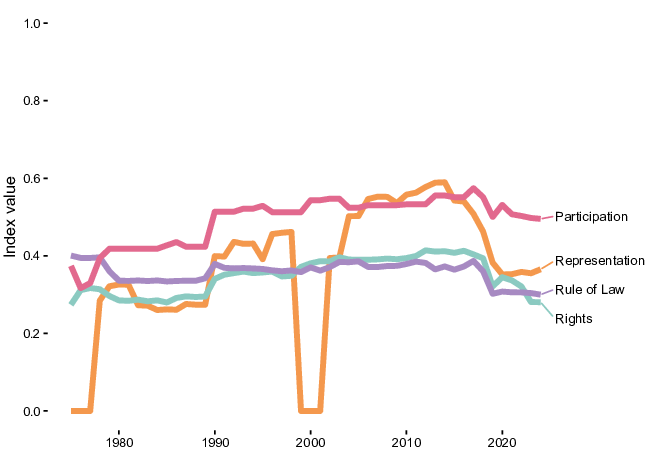

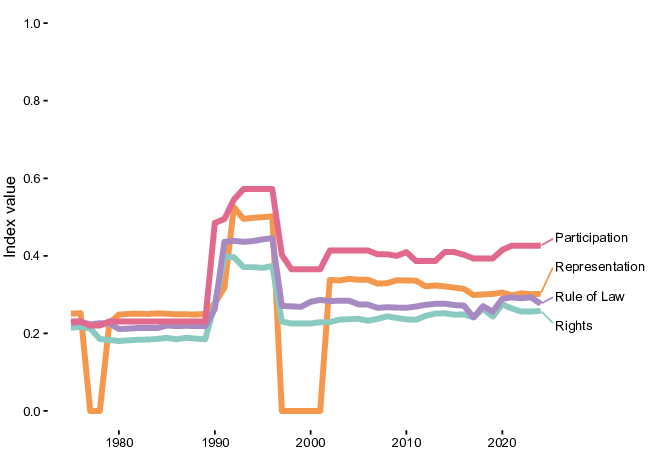

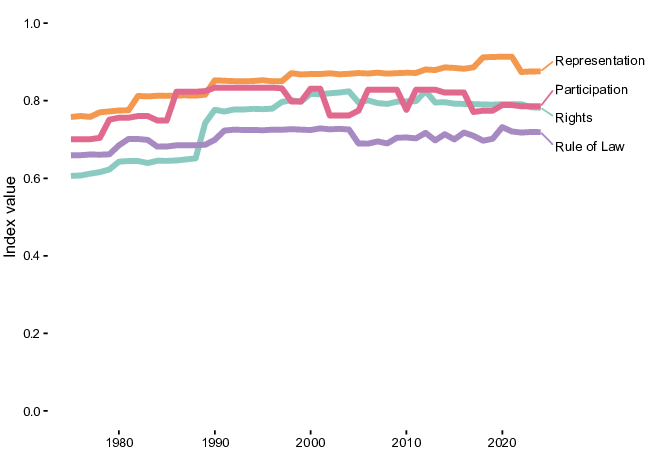

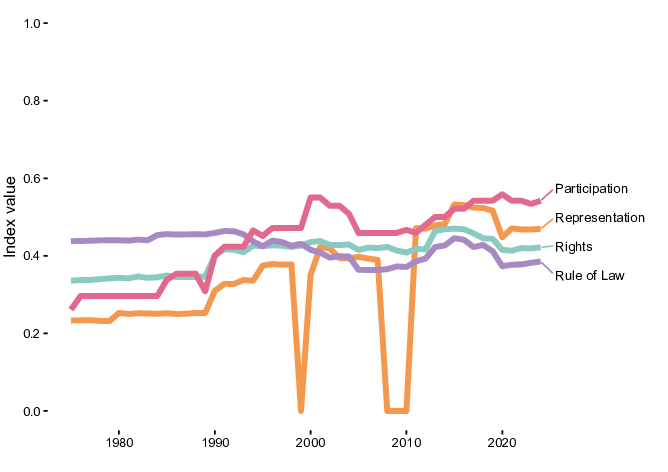

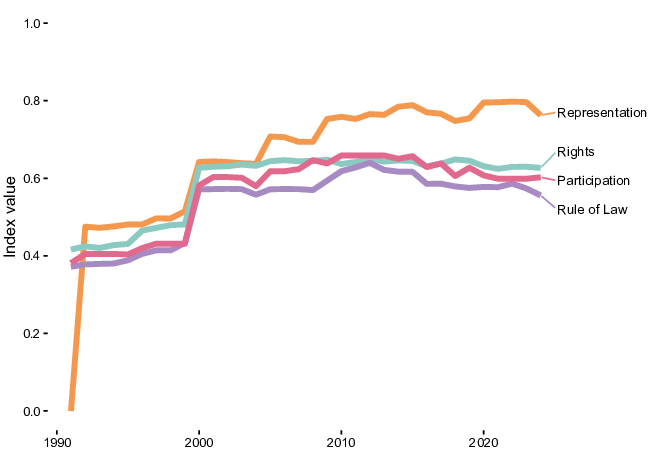

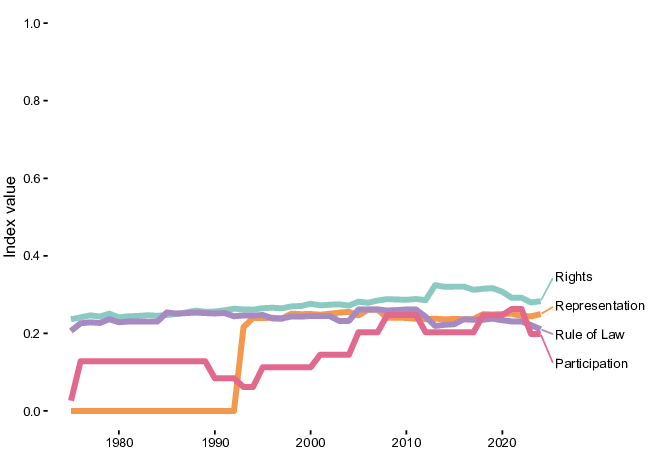

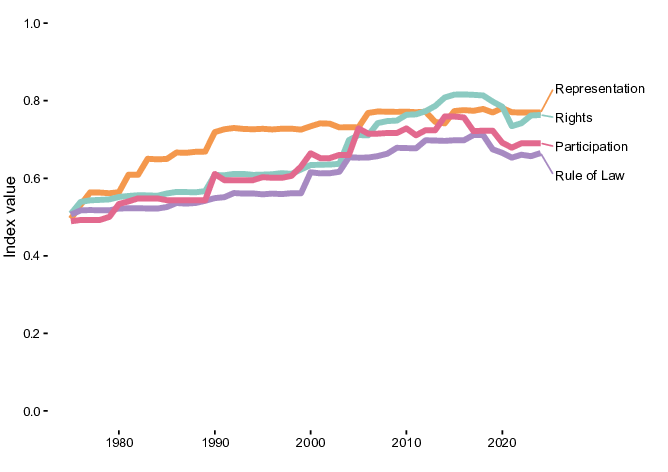

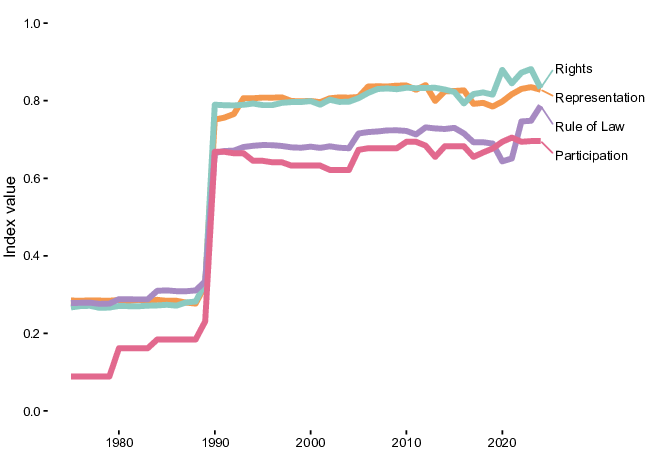

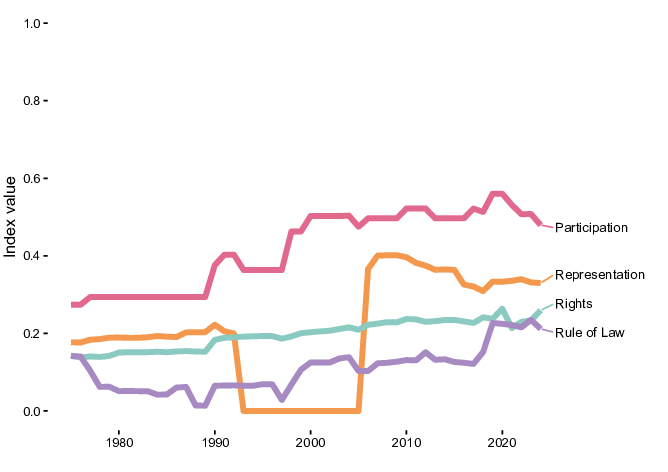

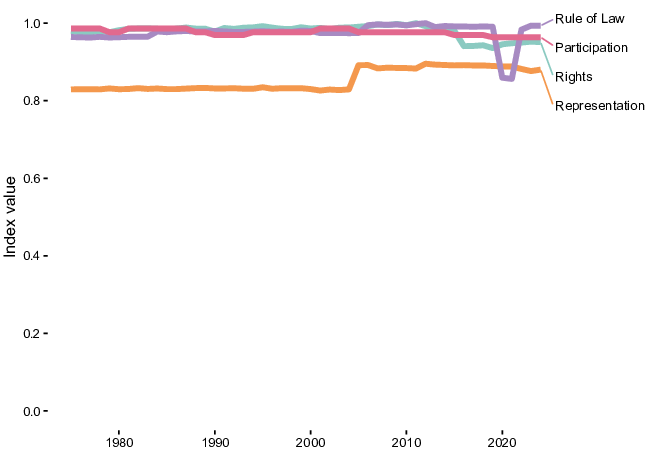

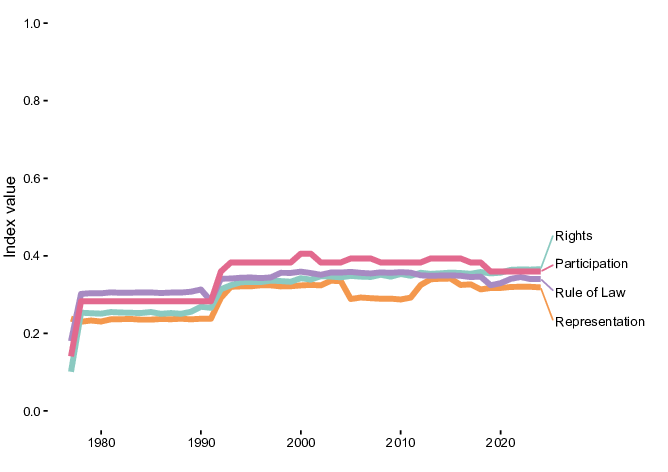

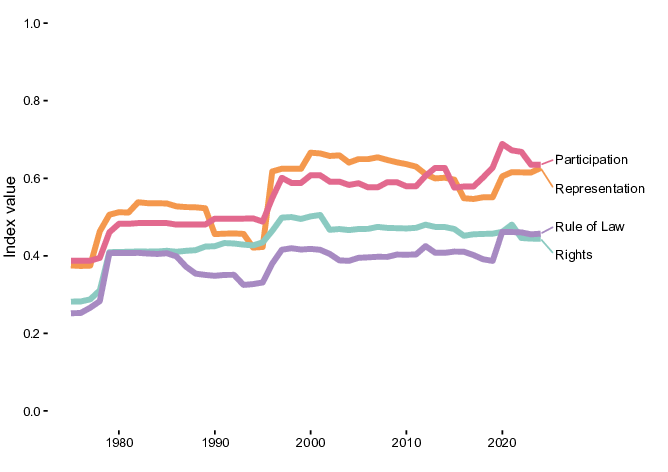

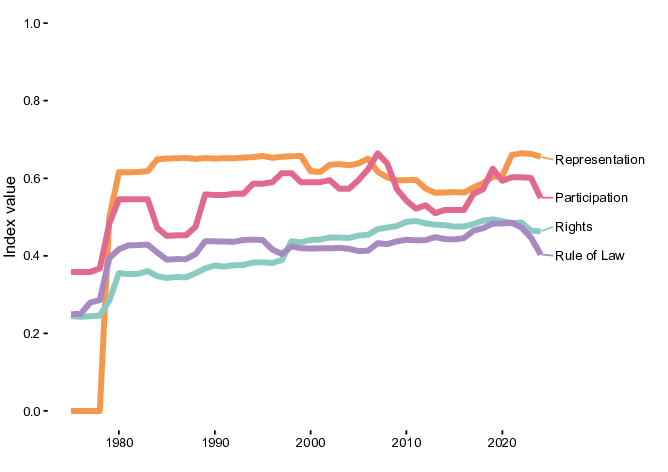

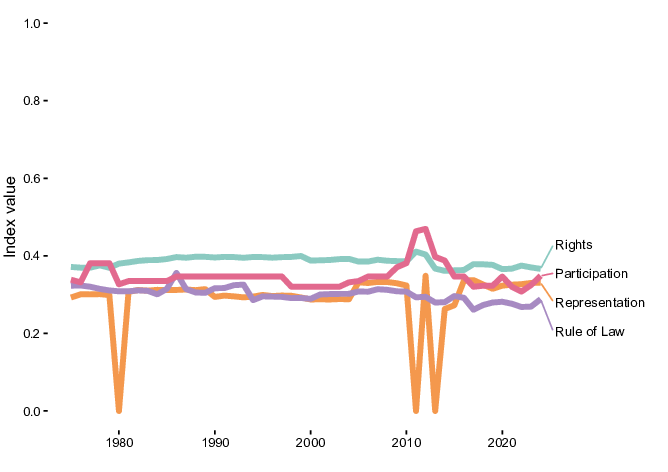

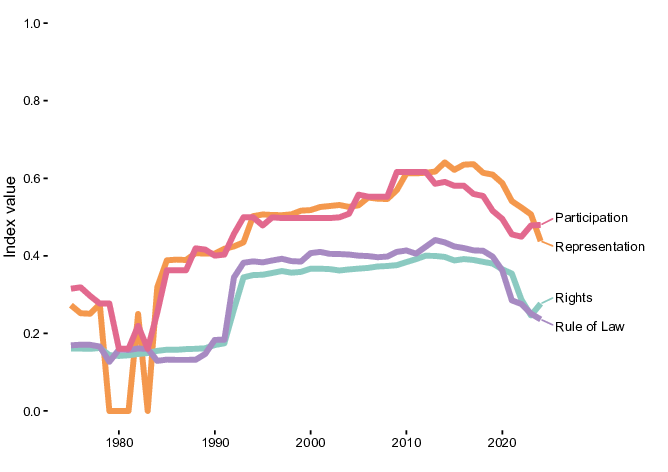

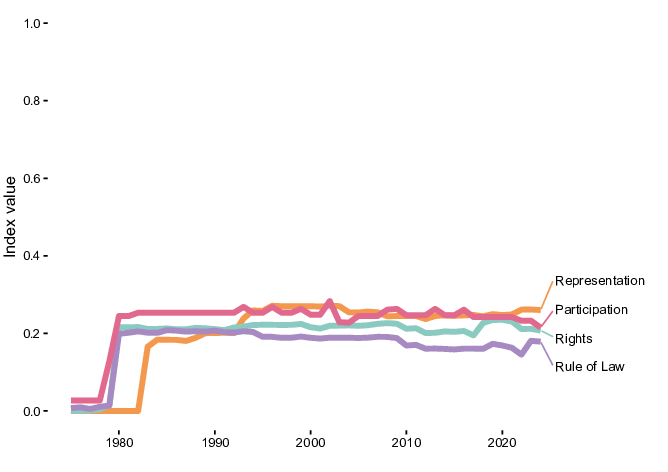

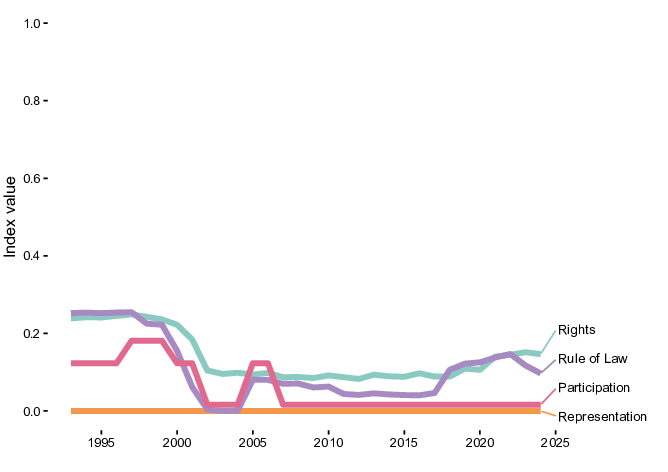

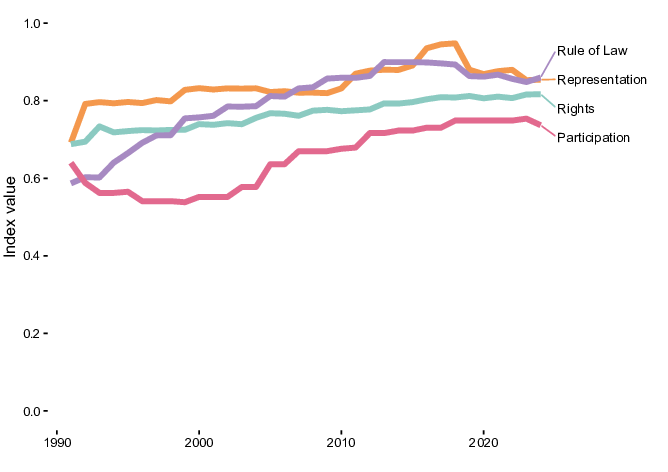

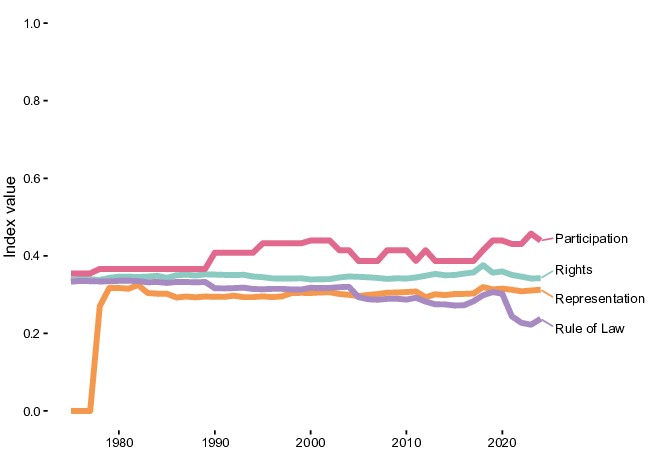

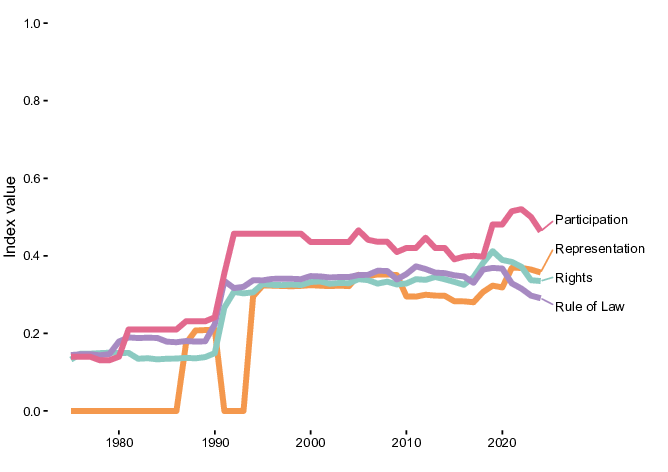

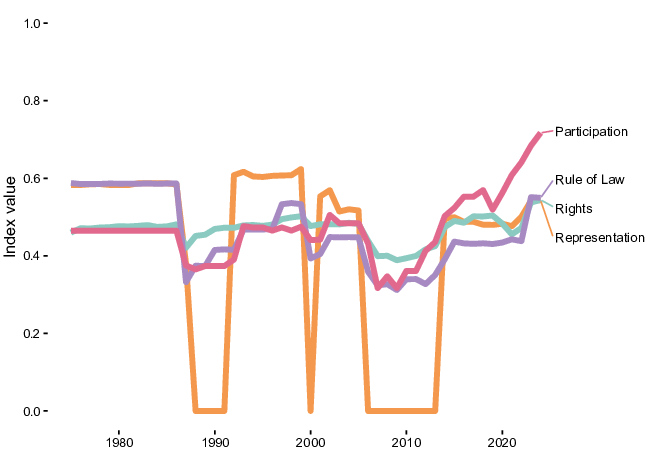

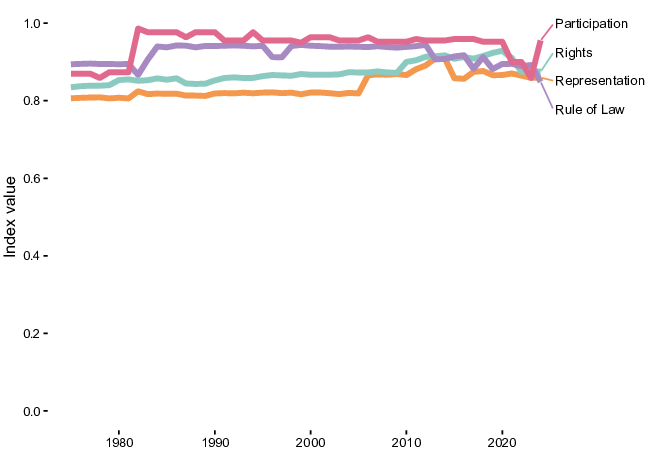

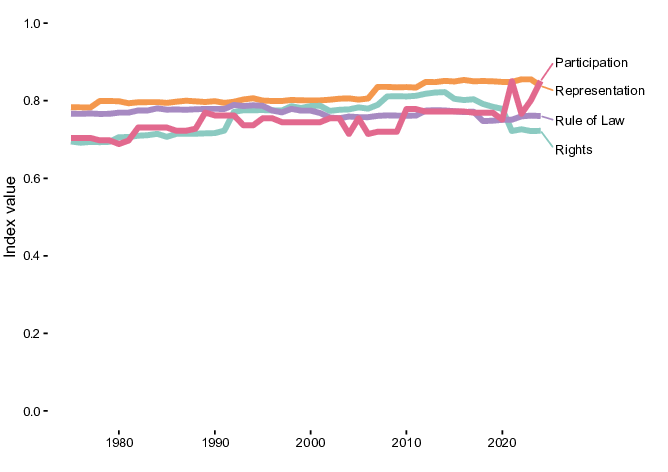

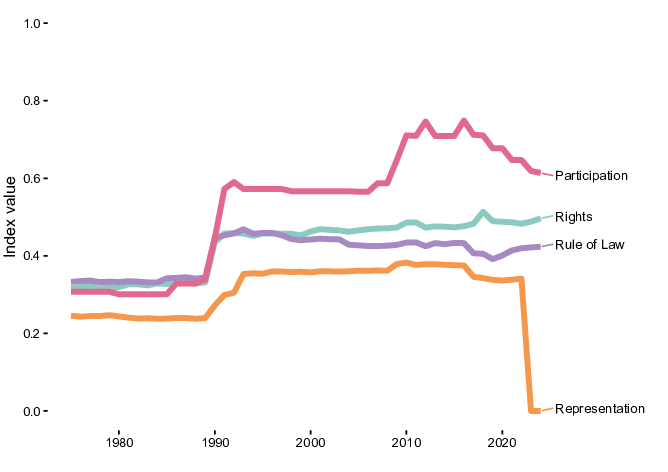

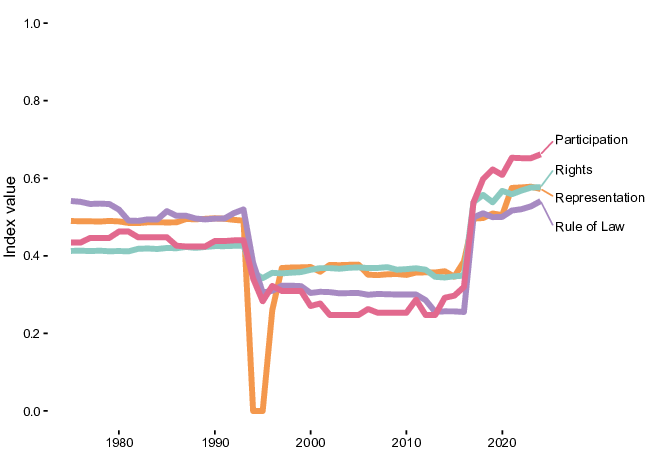

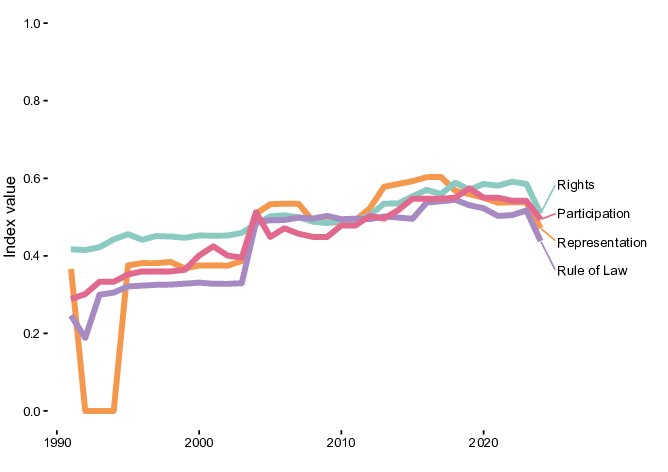

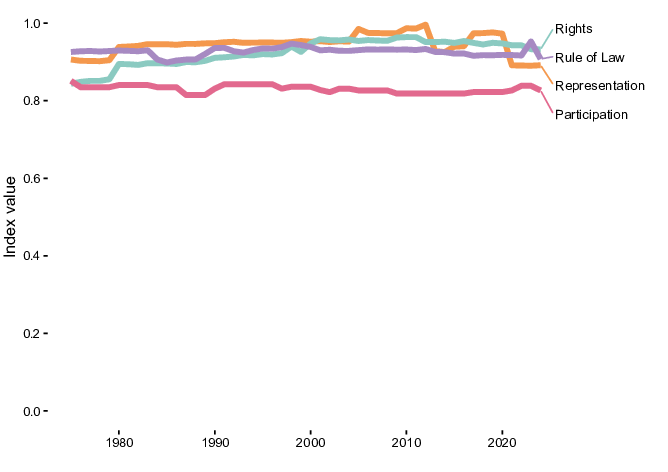

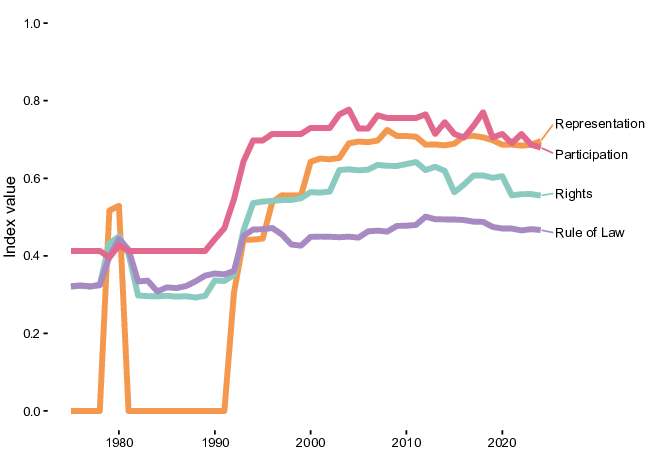

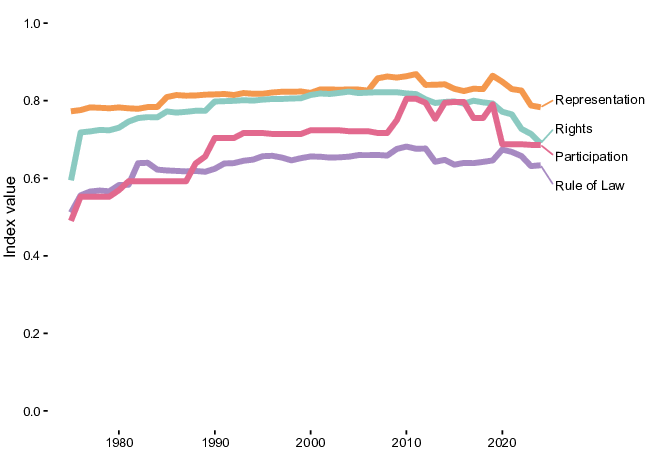

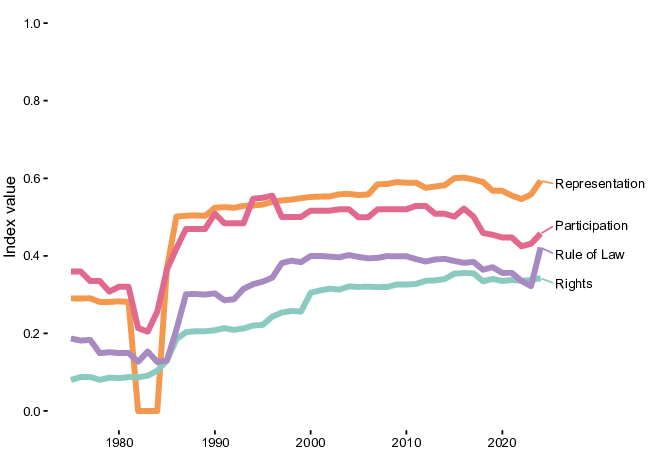

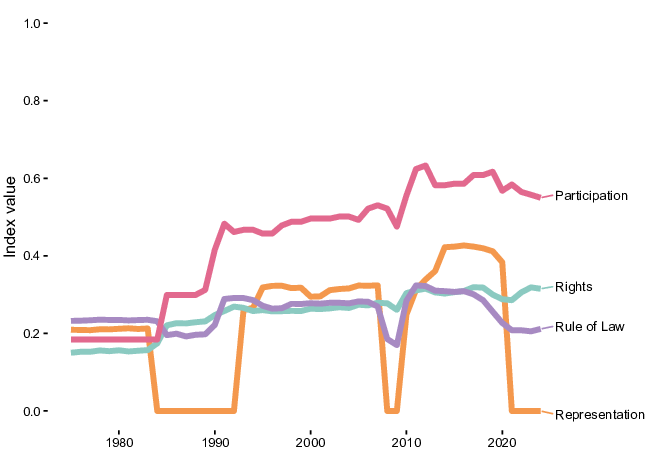

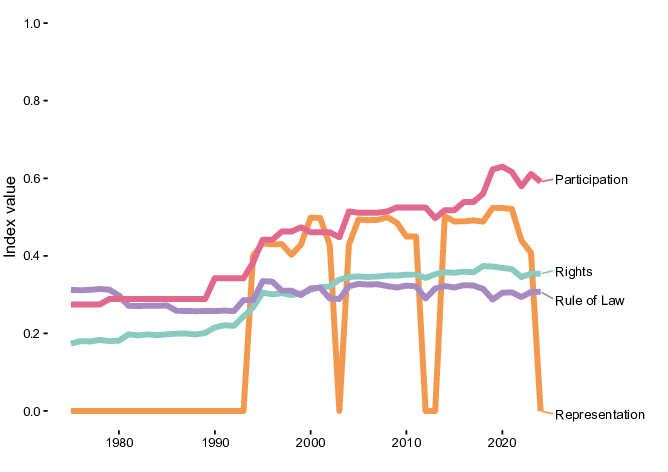

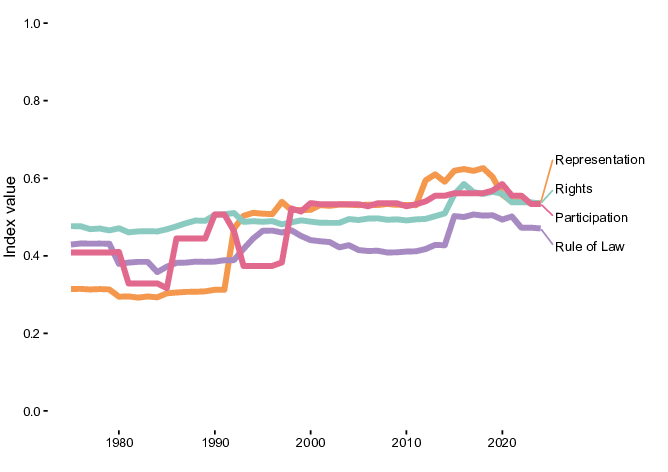

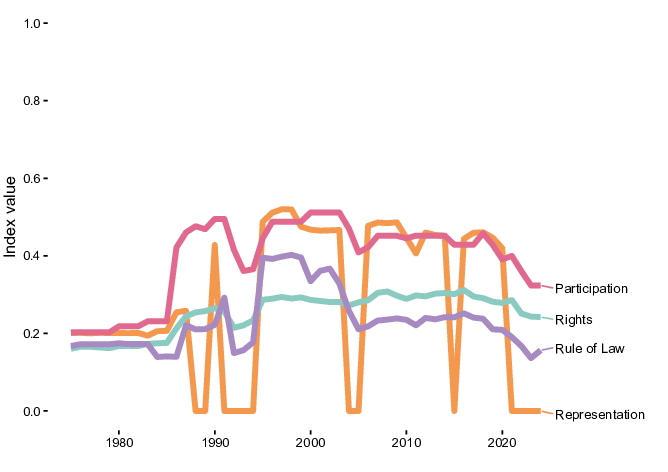

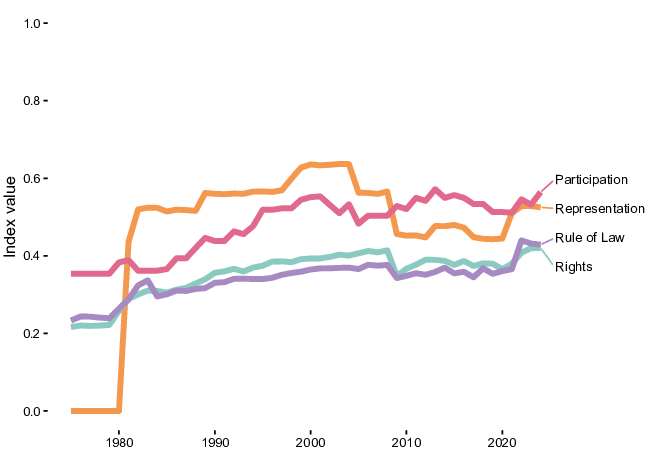

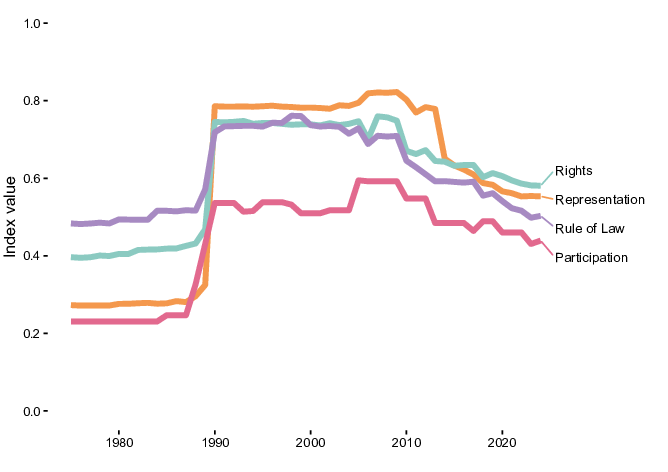

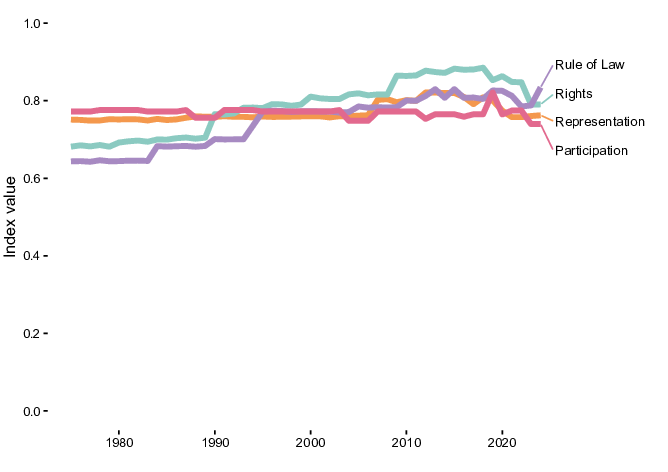

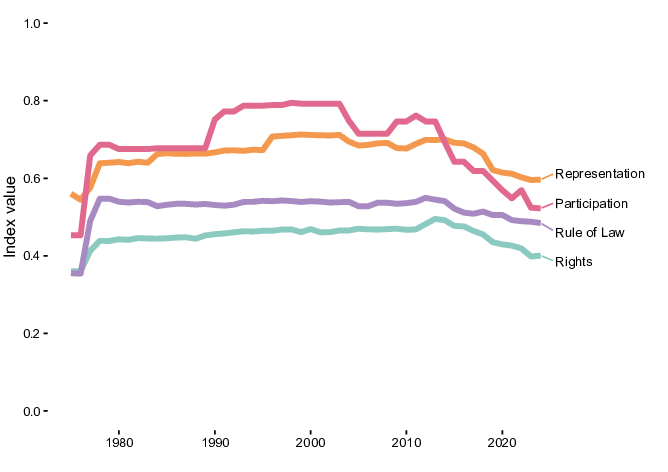

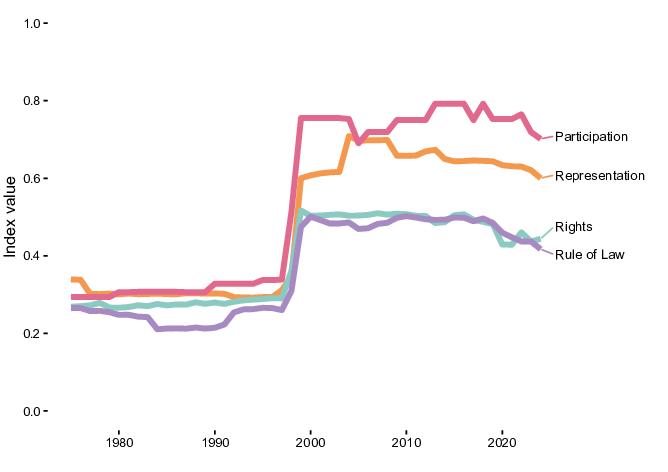

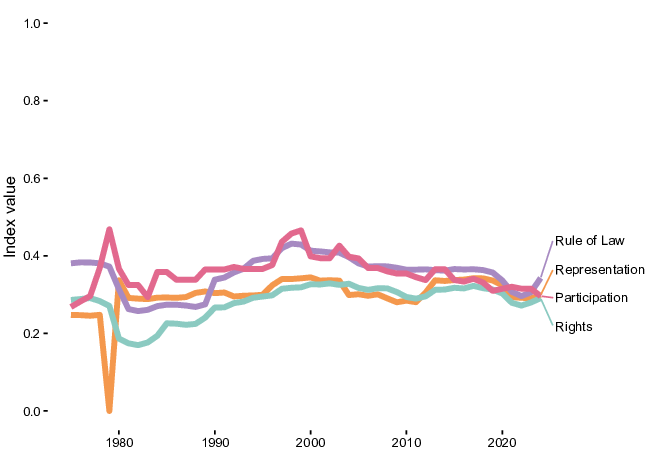

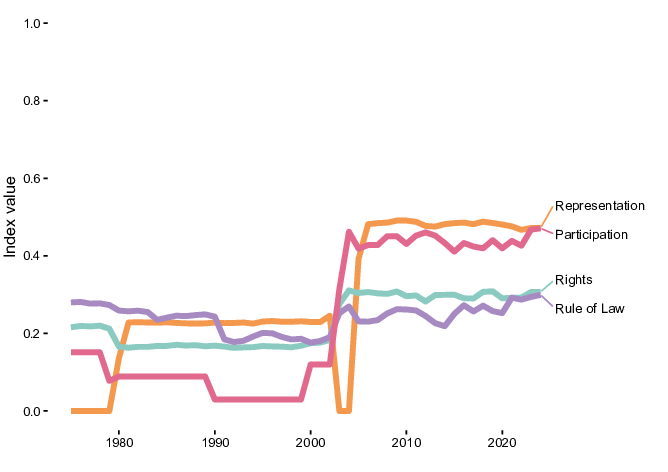

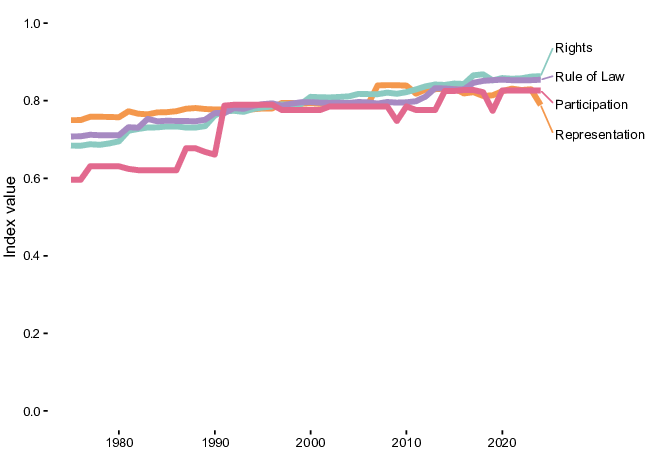

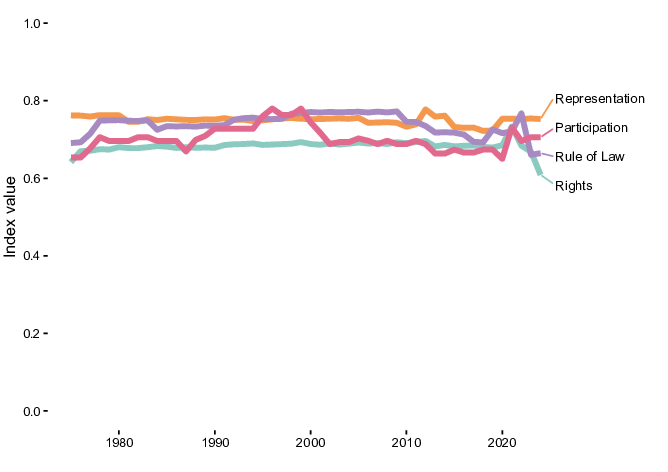

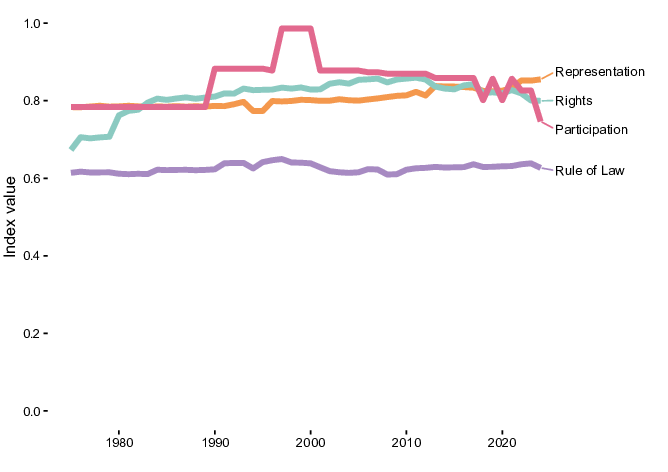

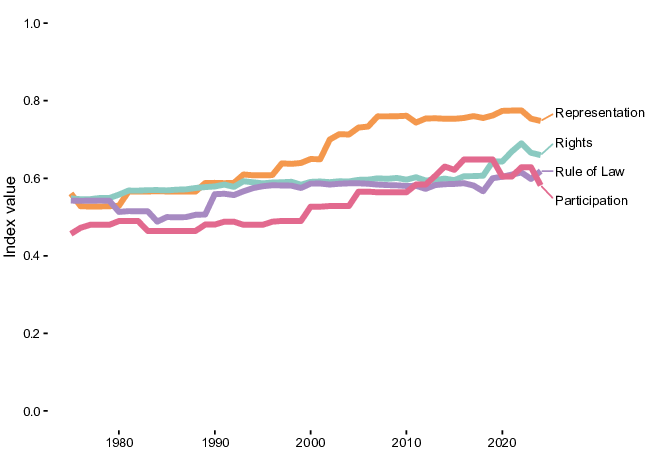

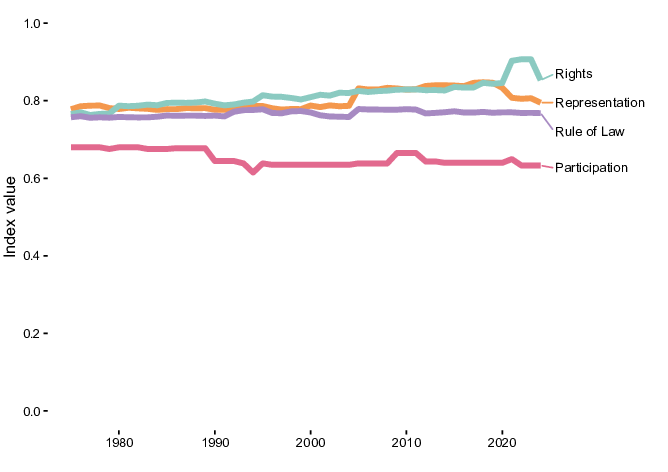

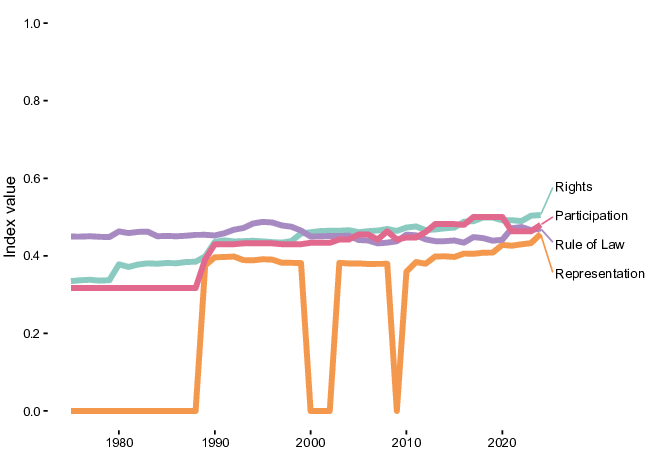

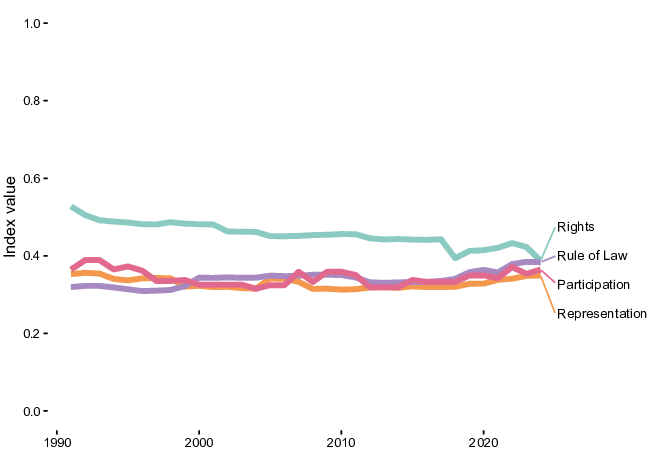

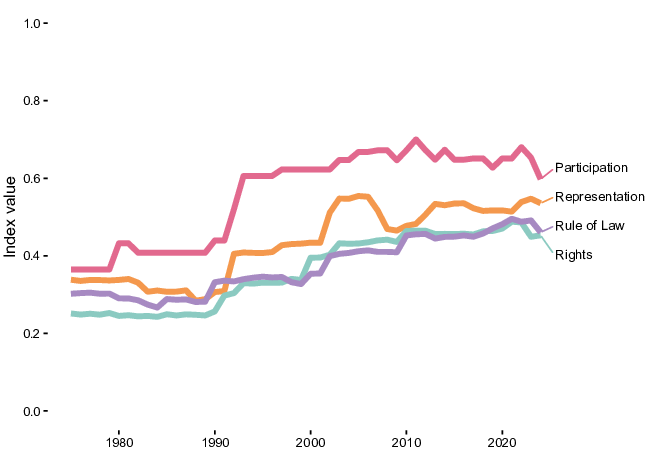

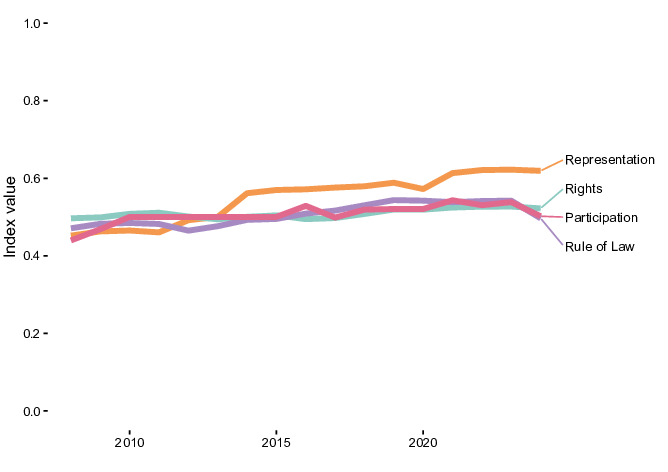

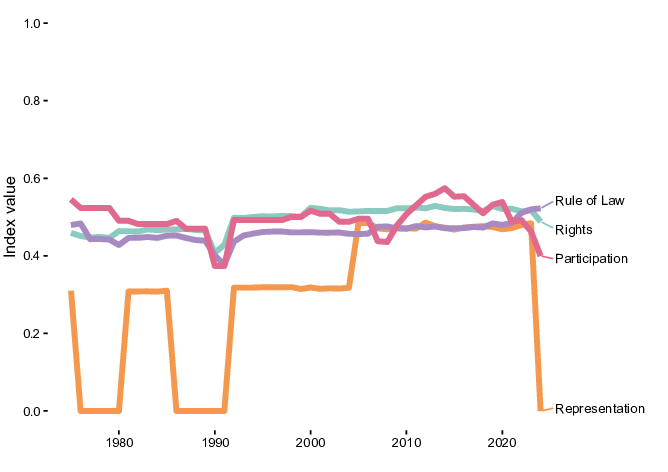

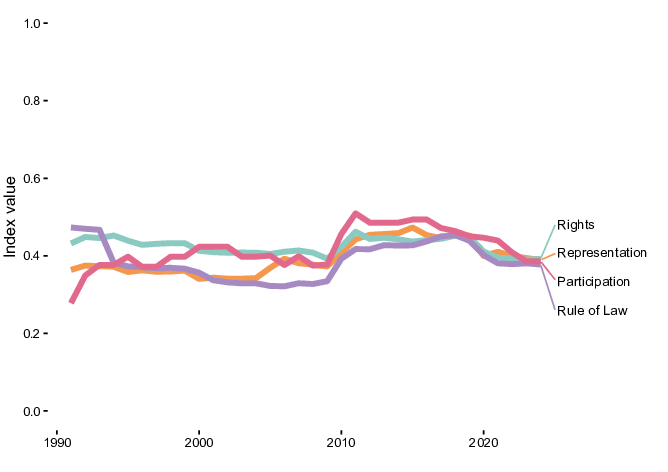

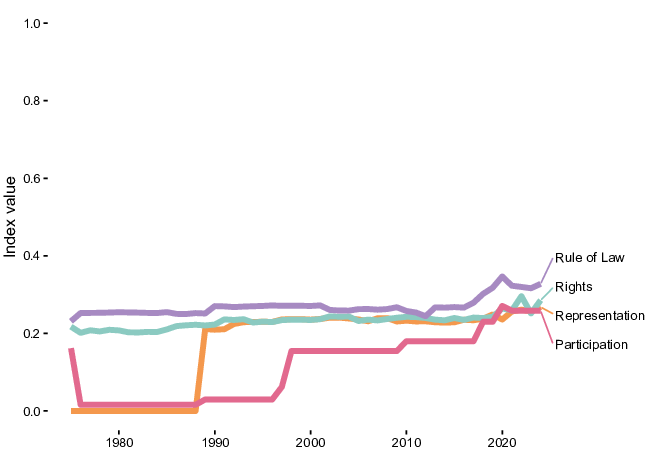

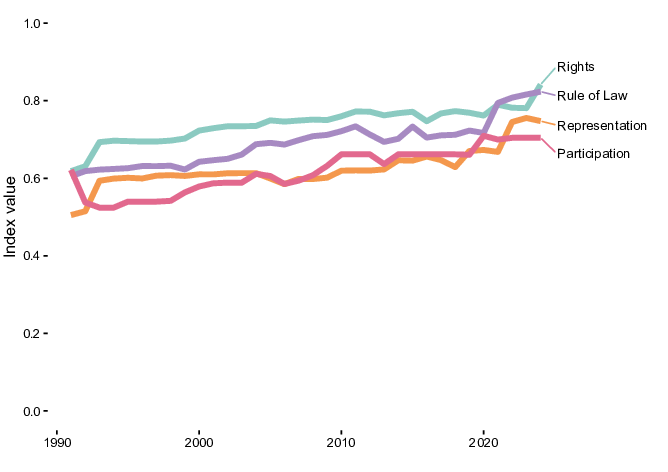

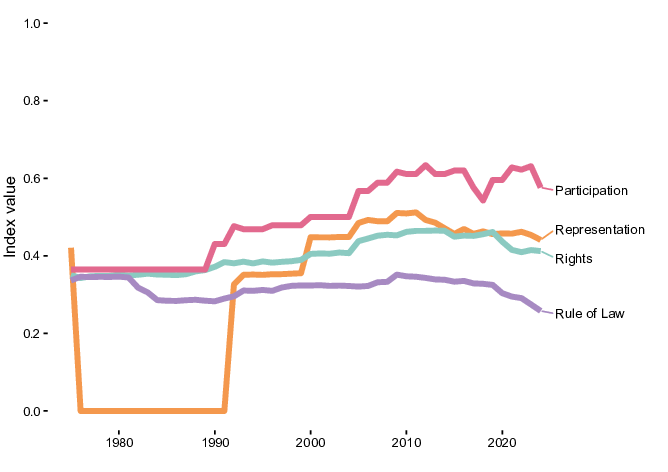

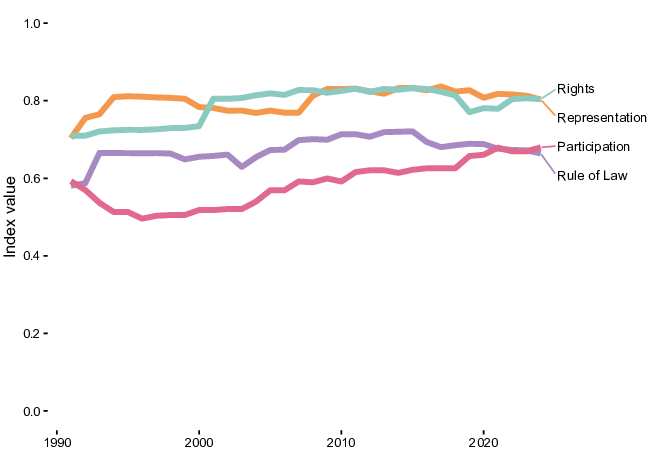

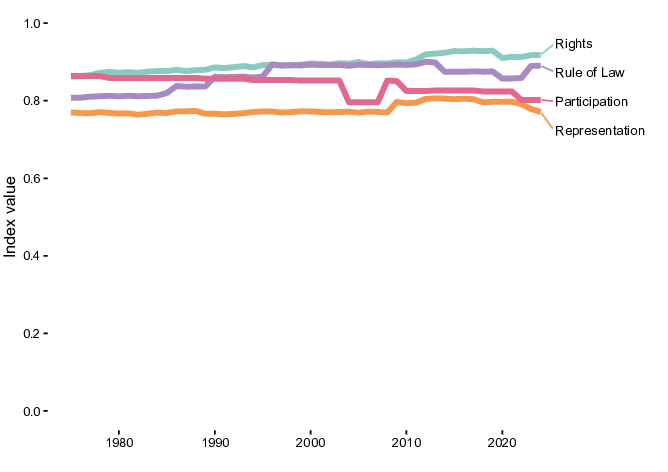

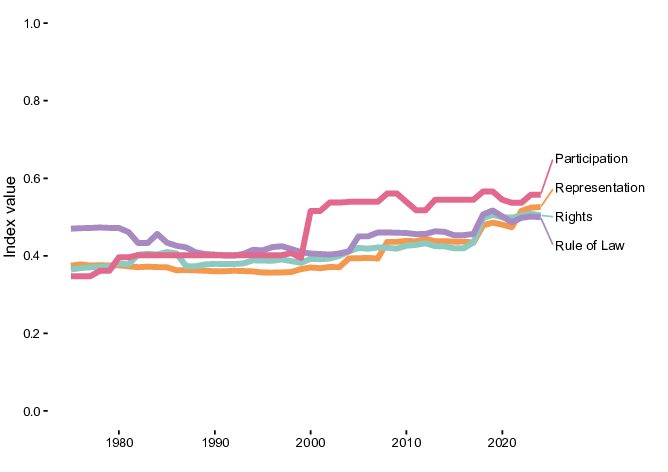

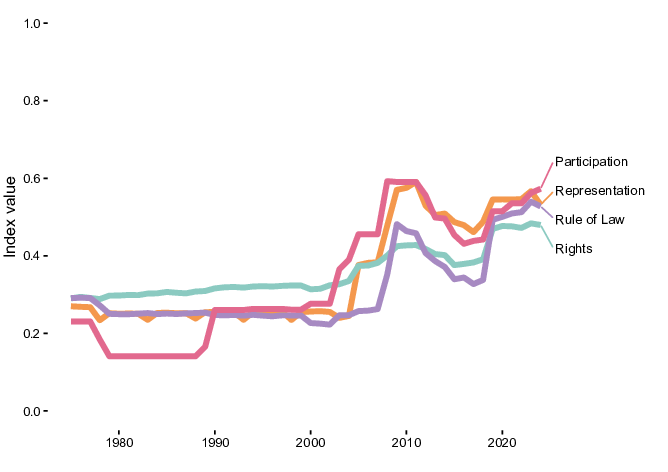

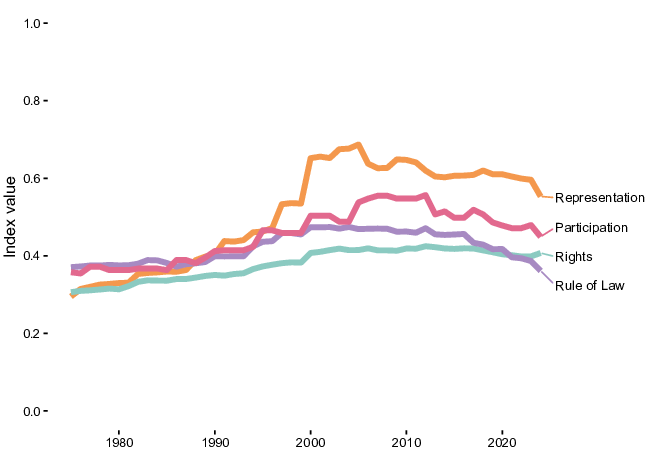

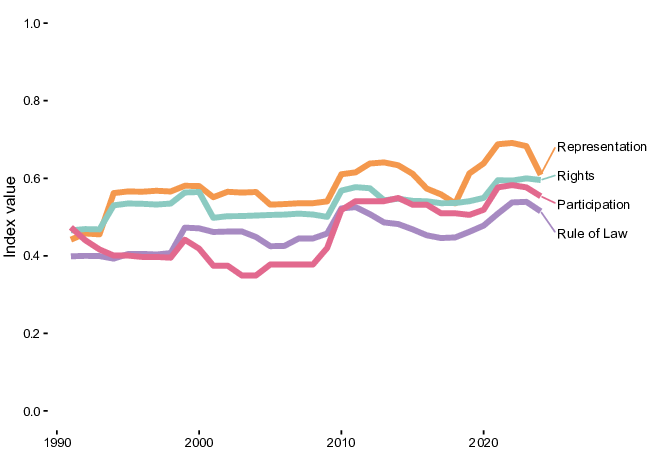

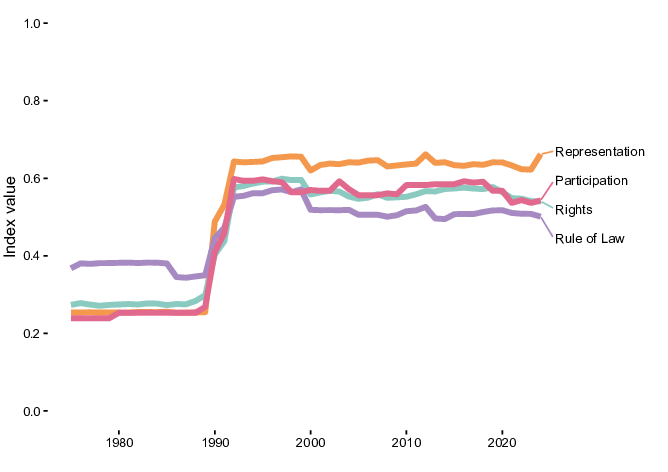

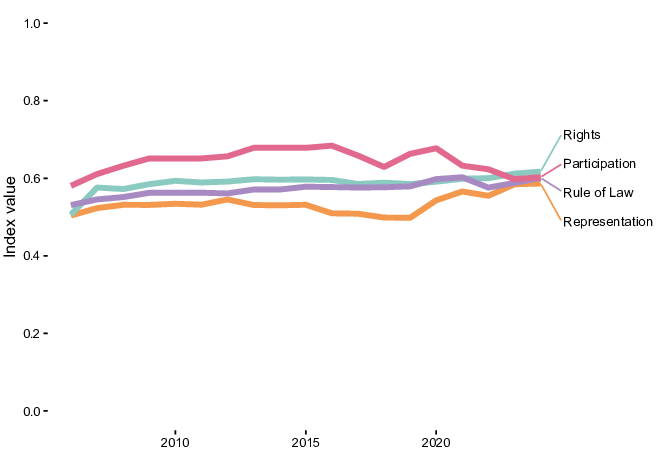

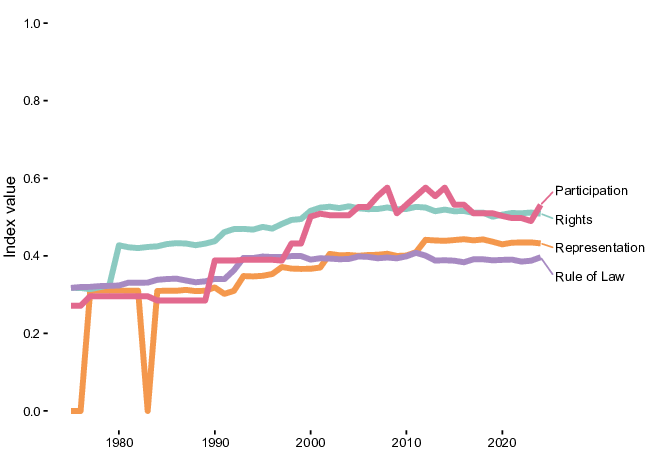

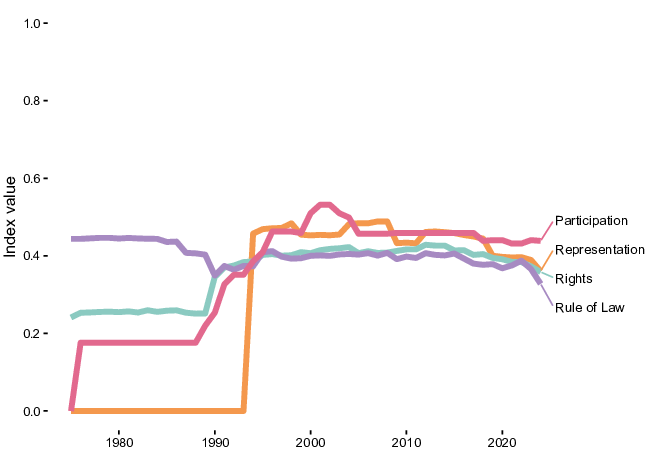

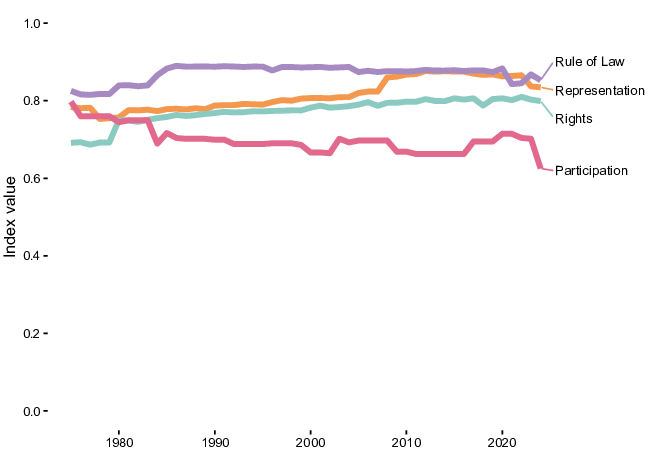

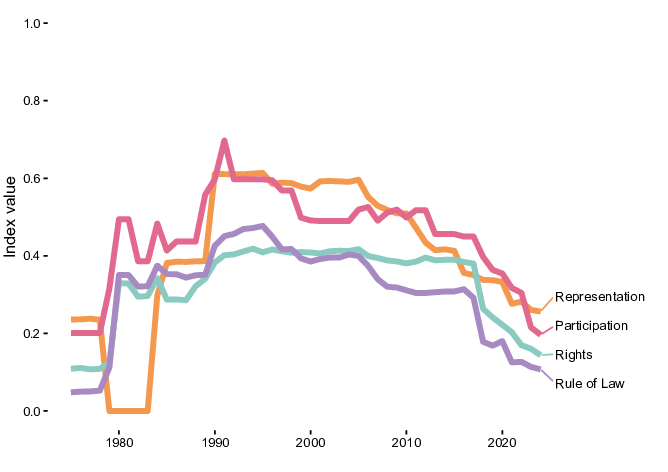

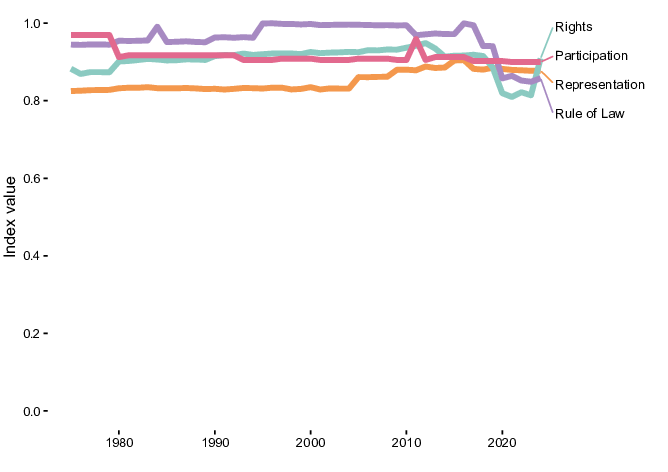

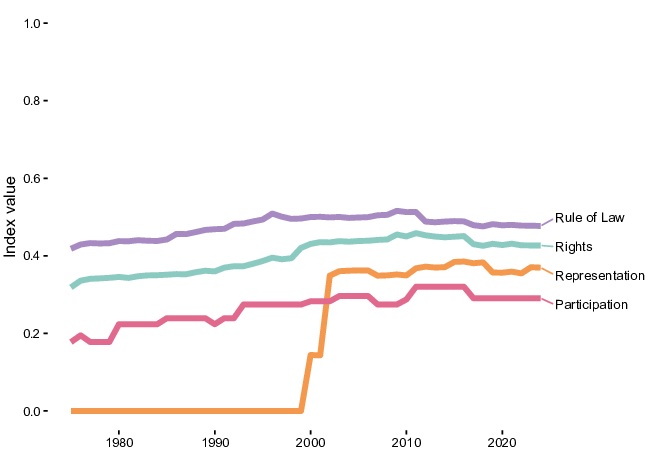

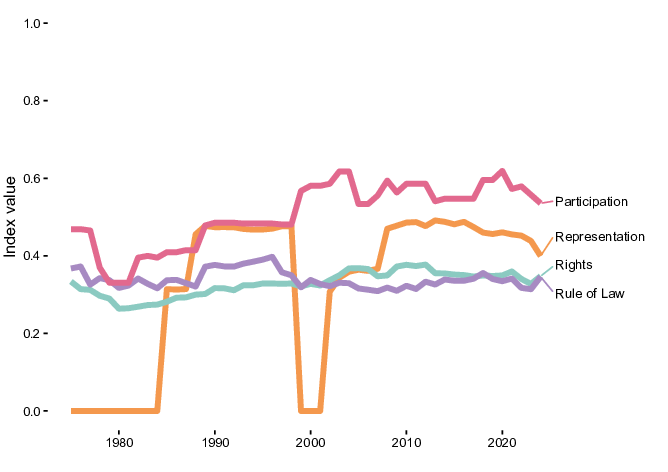

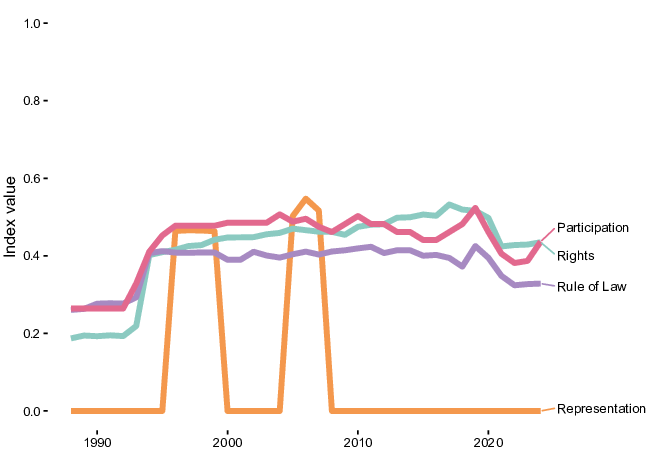

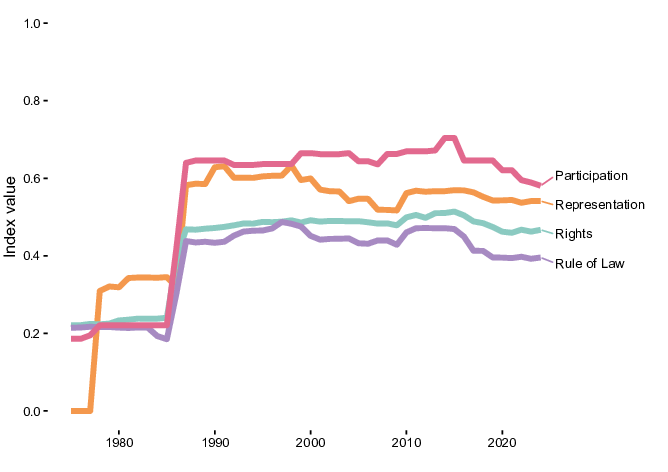

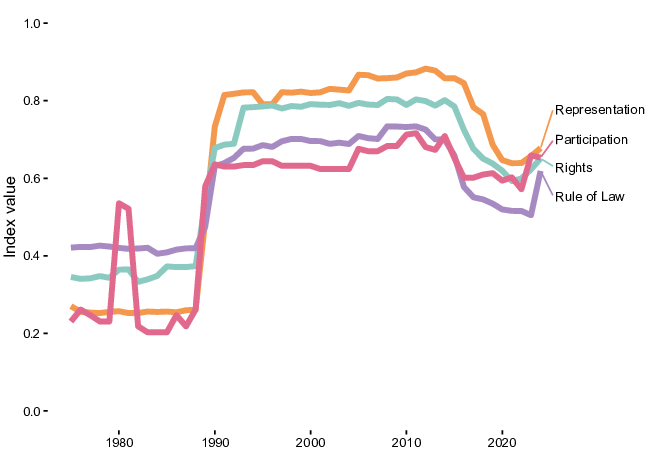

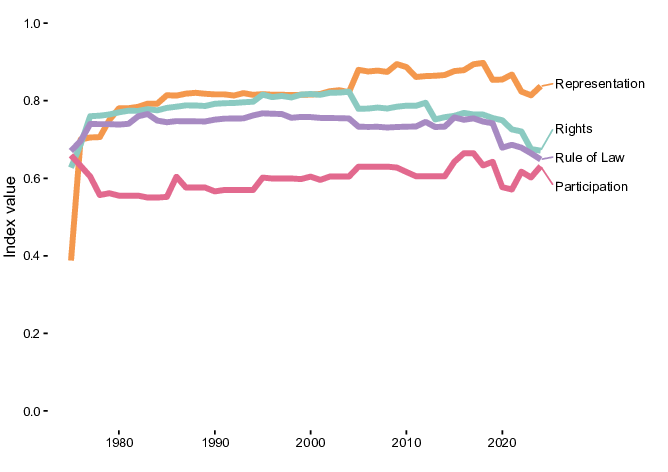

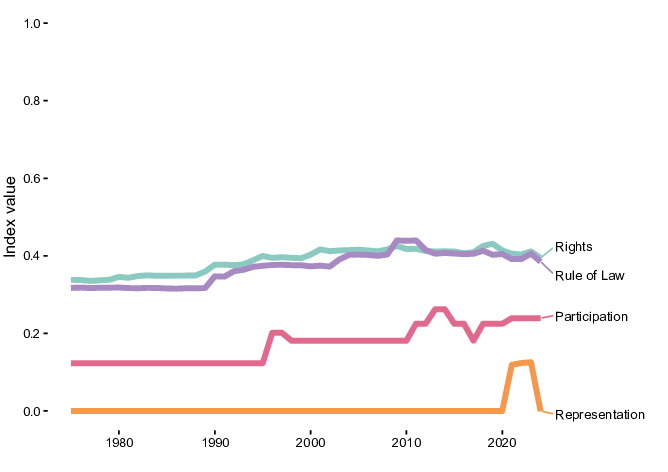

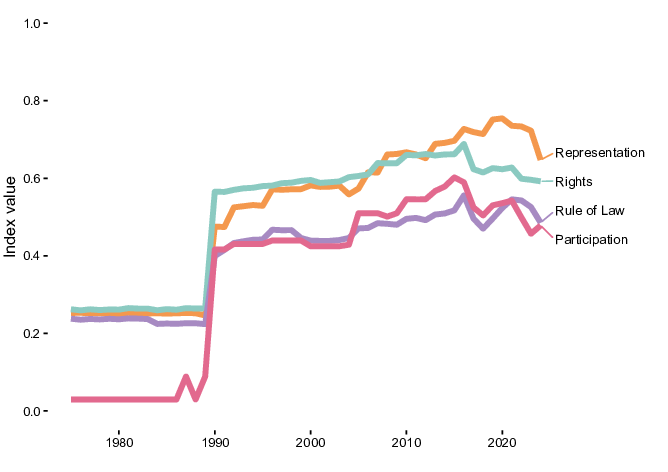

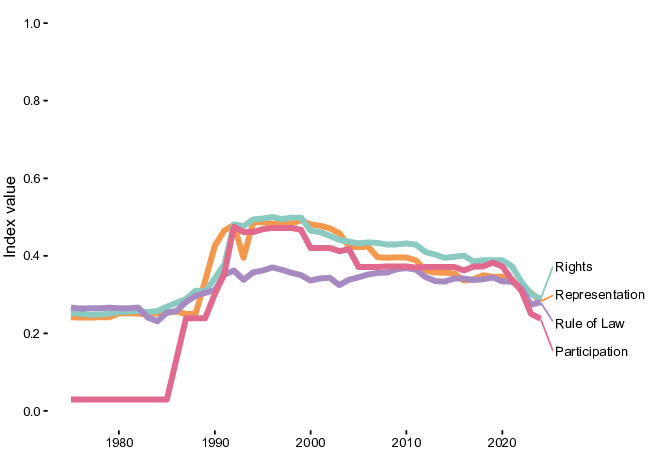

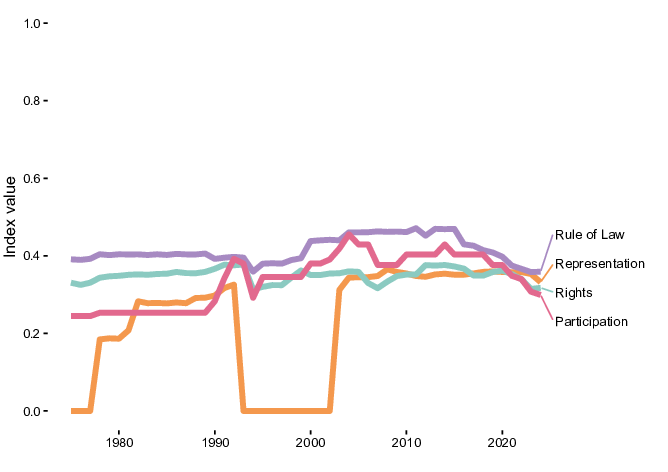

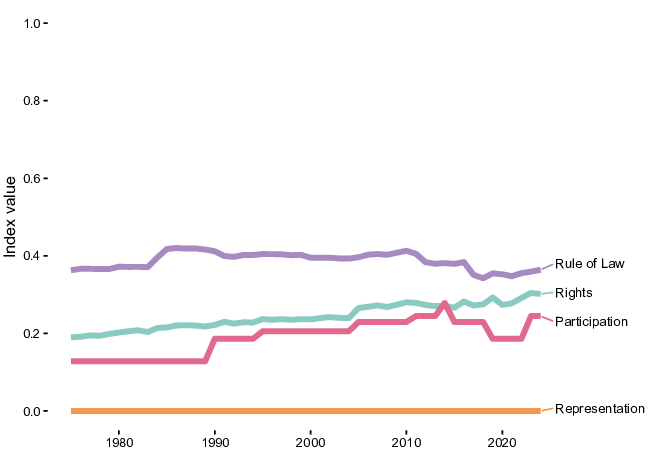

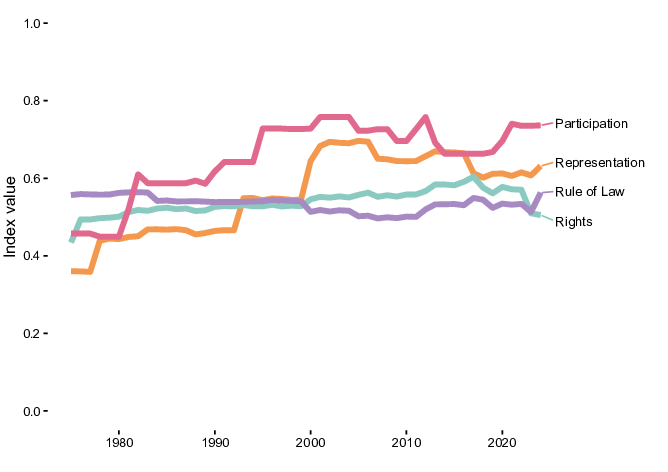

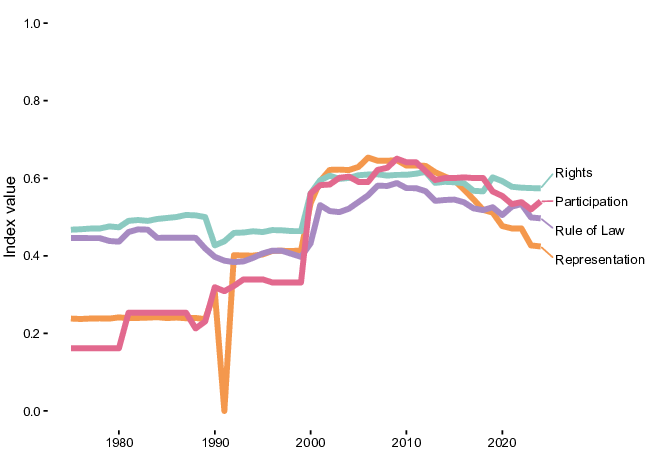

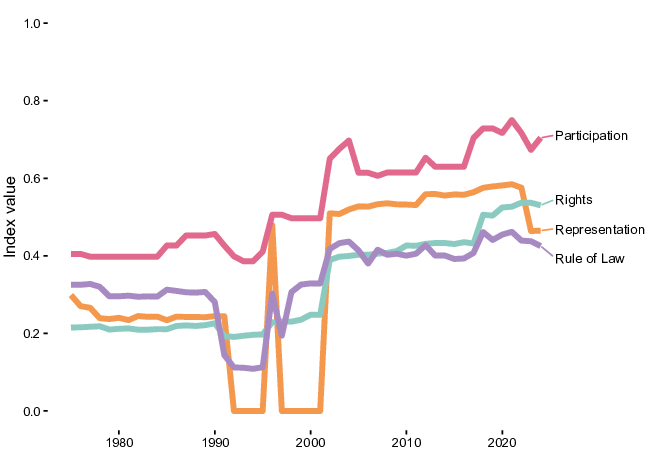

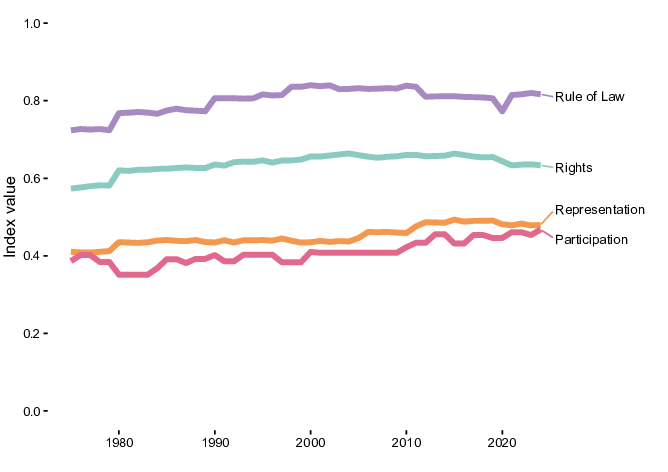

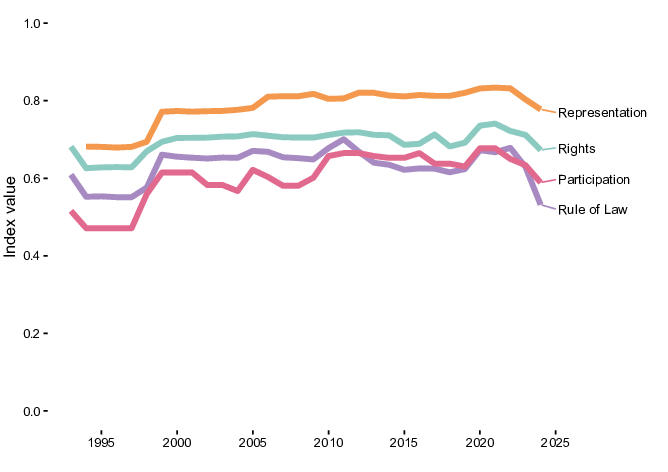

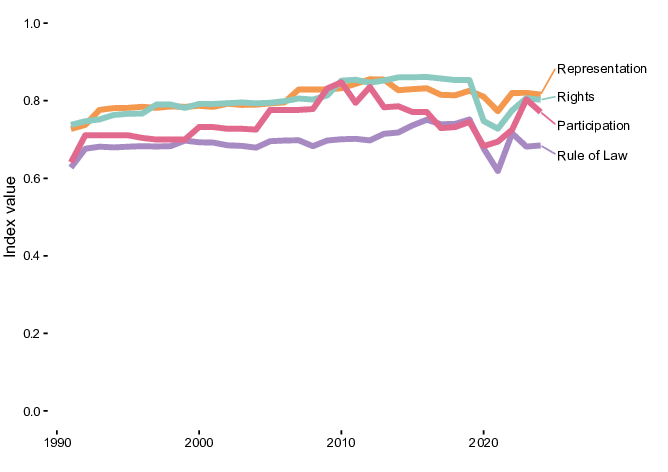

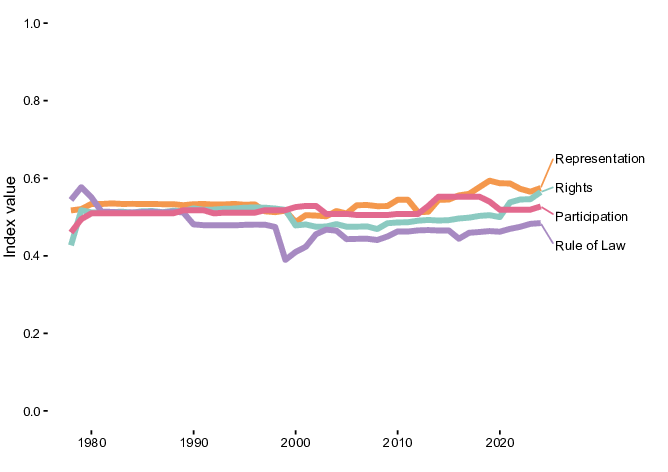

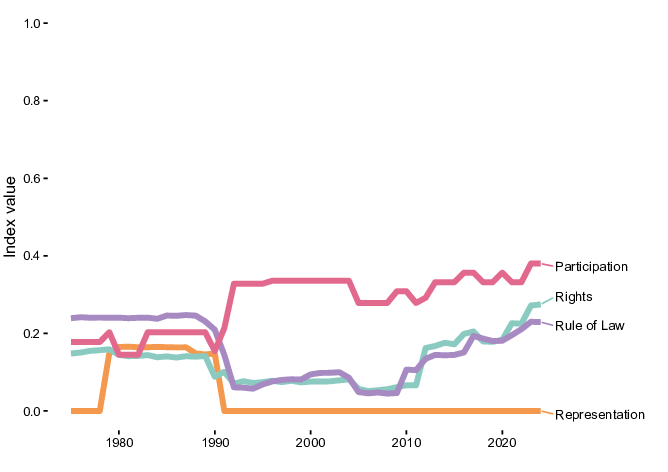

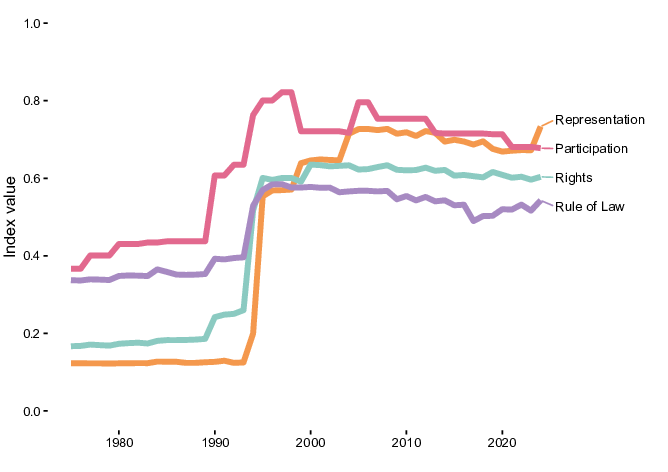

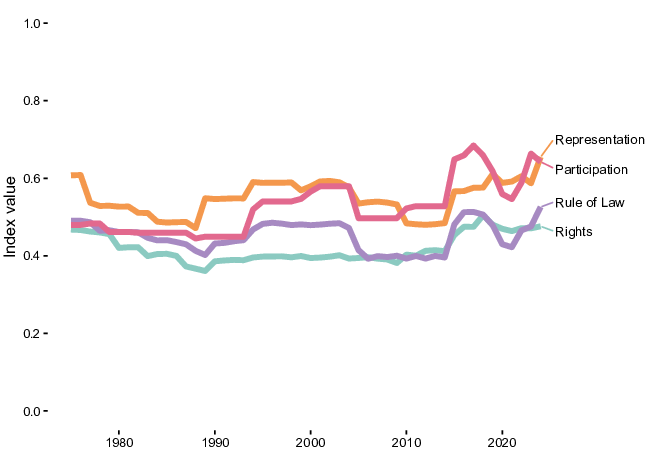

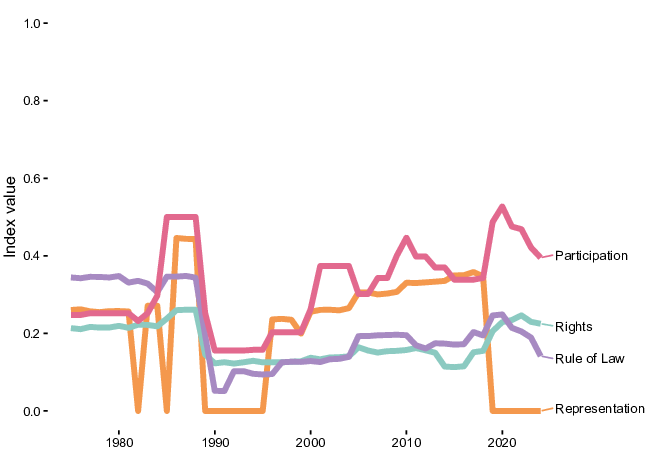

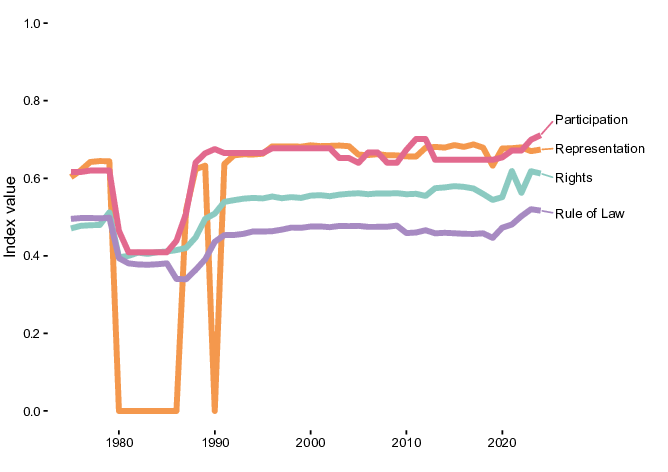

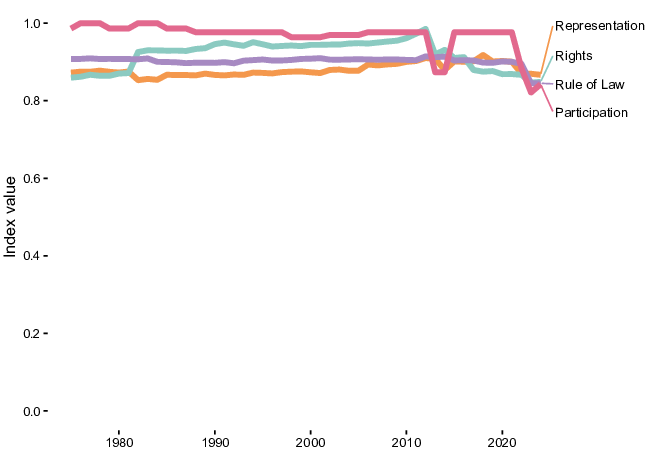

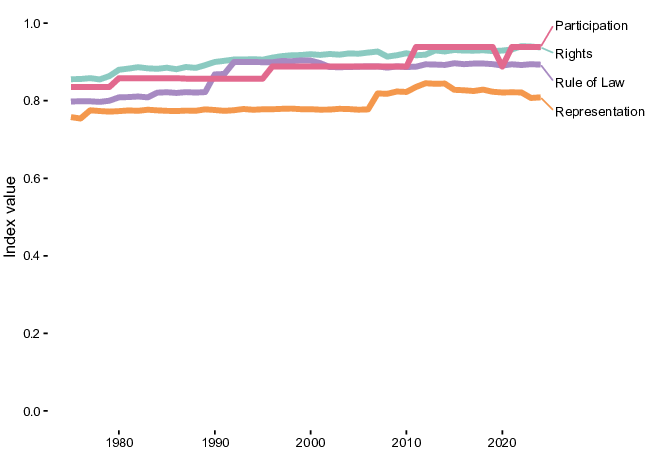

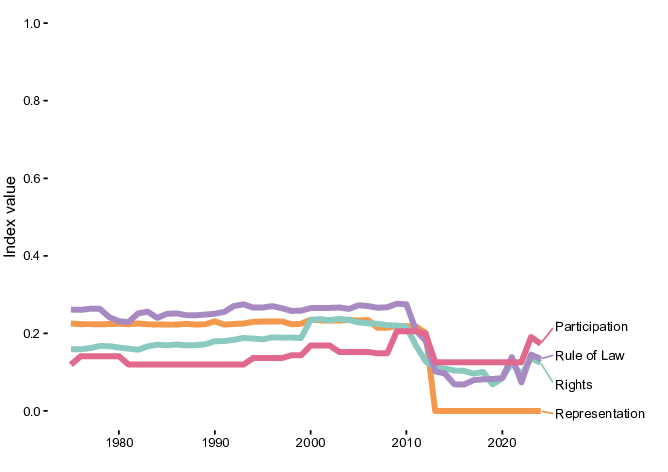

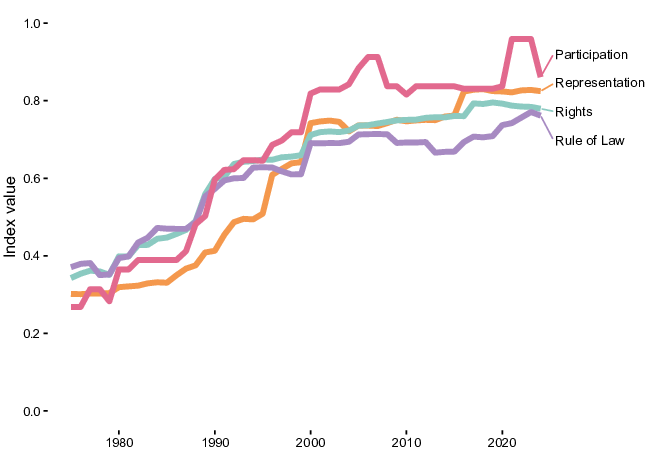

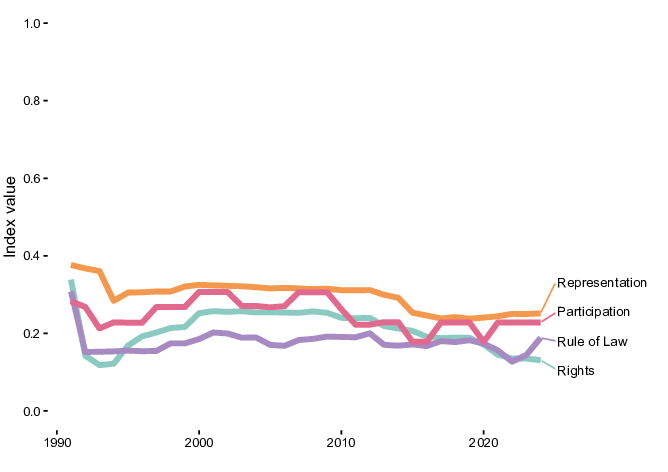

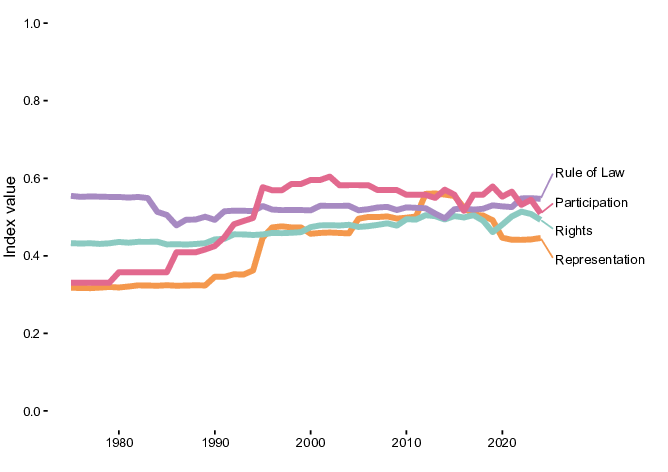

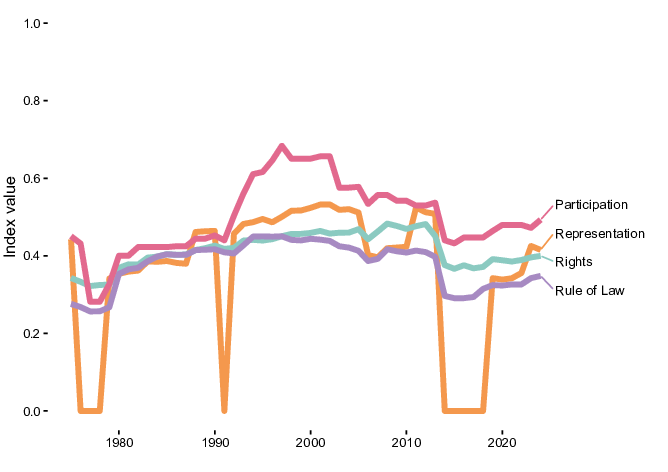

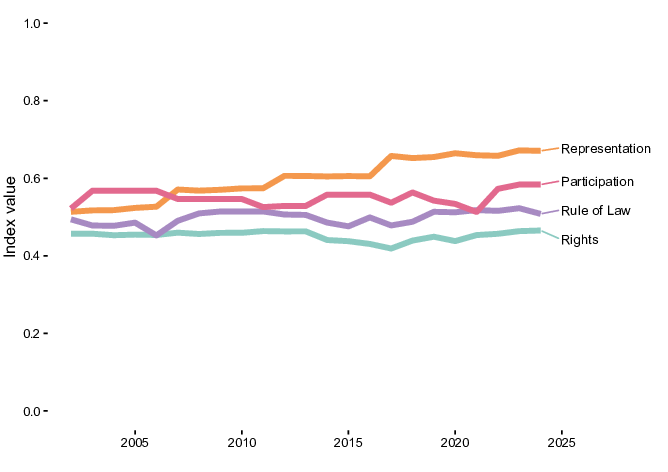

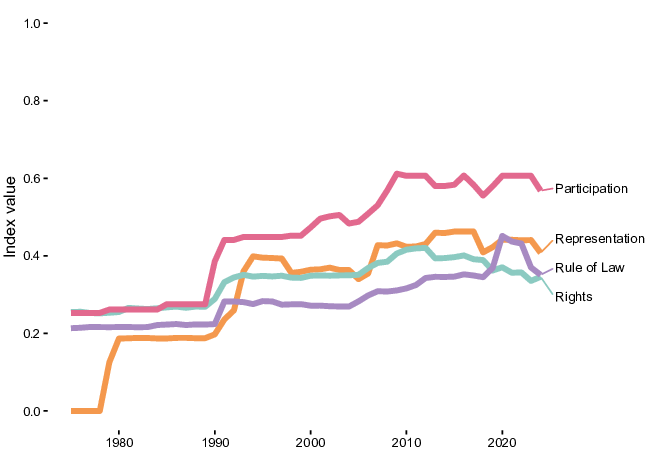

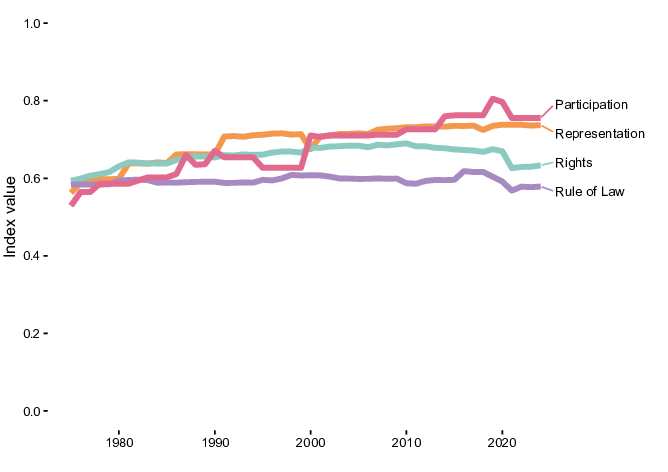

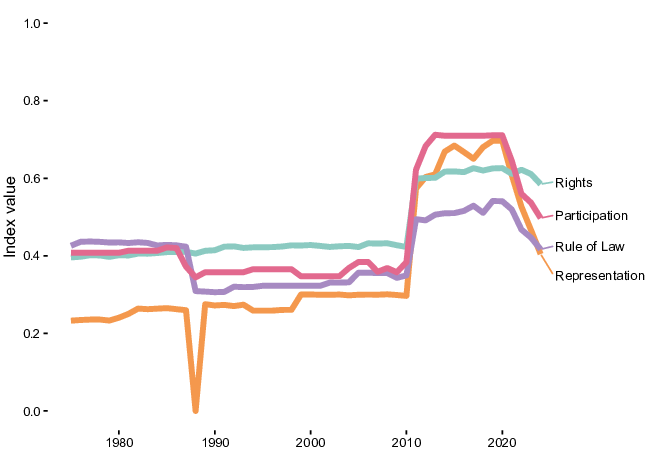

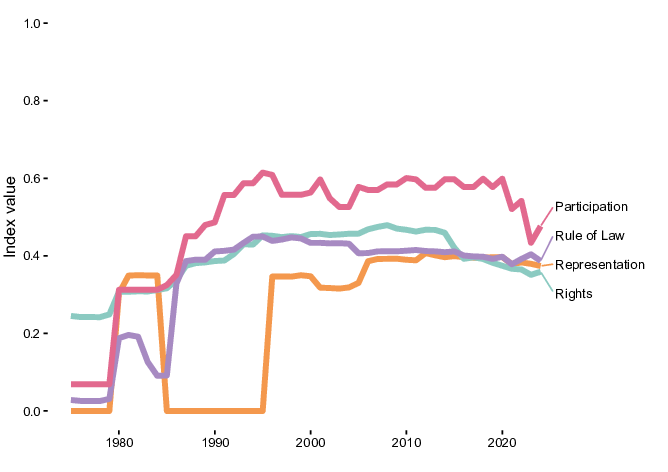

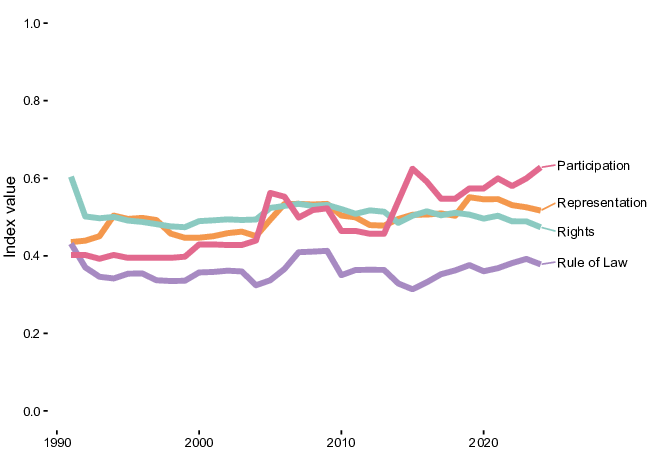

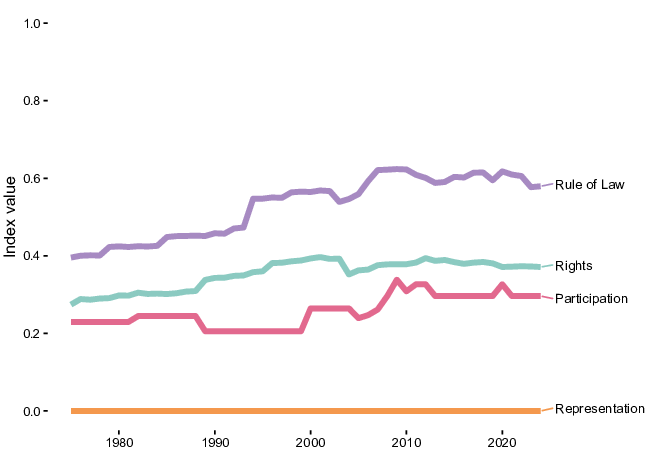

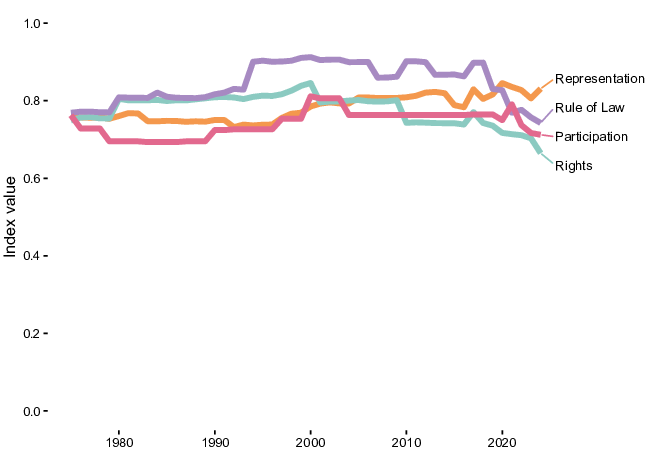

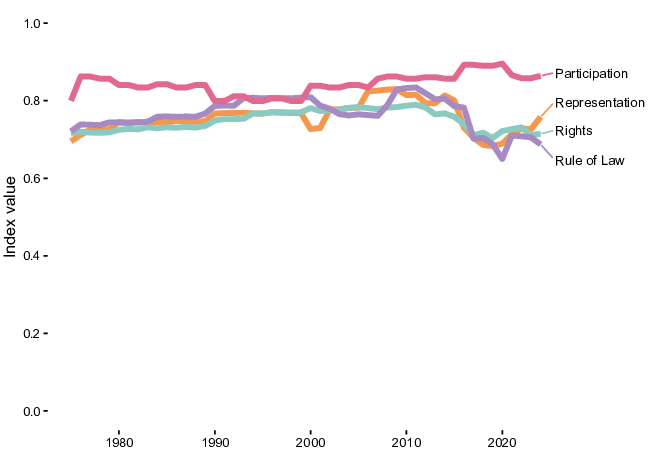

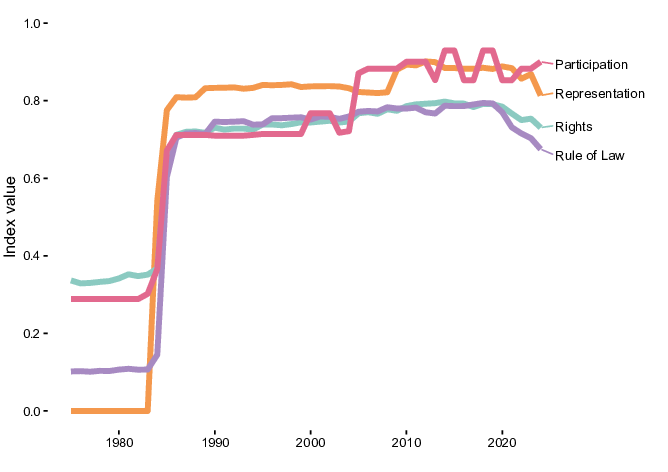

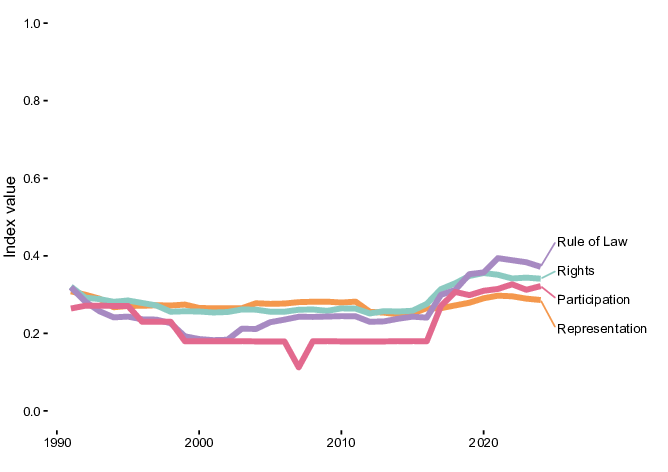

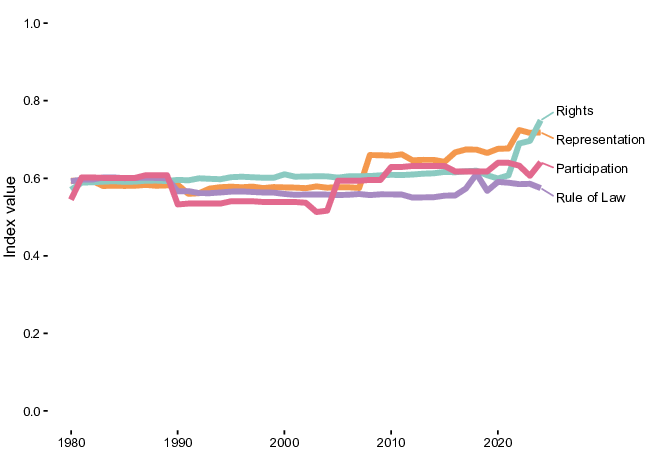

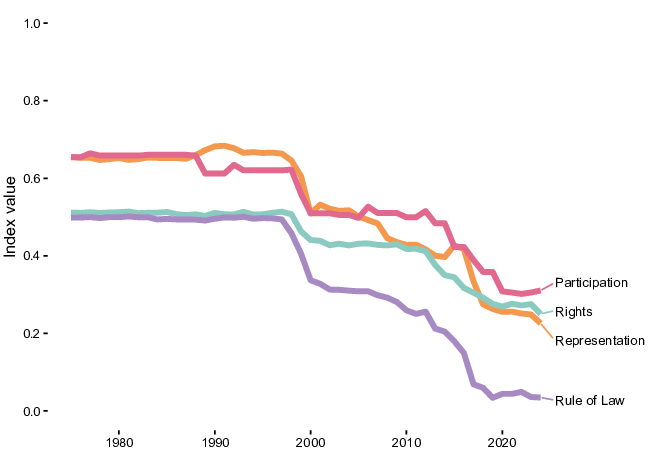

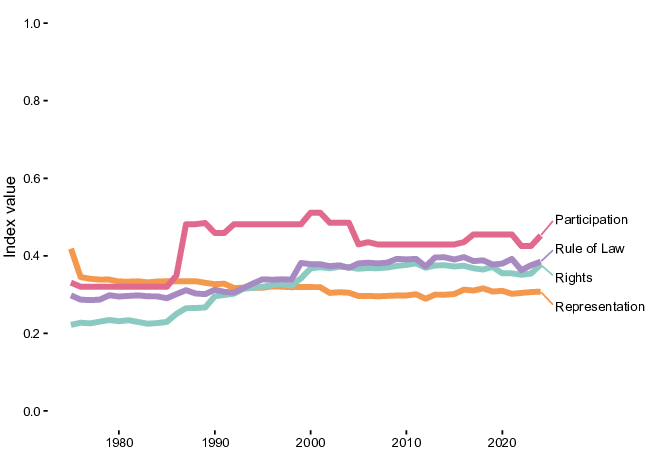

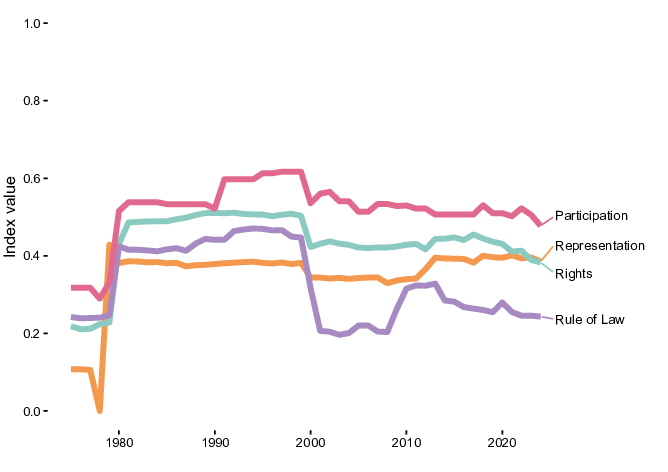

In addition to this macro trend, this year’s Global State of Democracy report reveals democratic instability at a thematic level. Representation is the strongest aspect of democracy overall, according to International IDEA’s indices. Yet, amid an unprecedented 74 national elections in 2024, Representation scores collapsed to their worst level in over 20 years, with seven times more countries declining than advancing. Meanwhile, Rule of Law—the weakest overall performer—fell most strikingly in Europe, where performance has been historically robust. Only Participation scores stayed relatively constant, confirming our previous findings that much of democracy’s lingering resilience comes from civic engagement, including in regions suffering deterioration in other aspects of democracy.

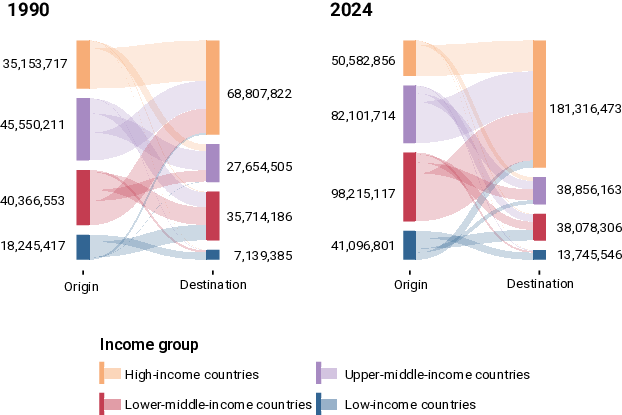

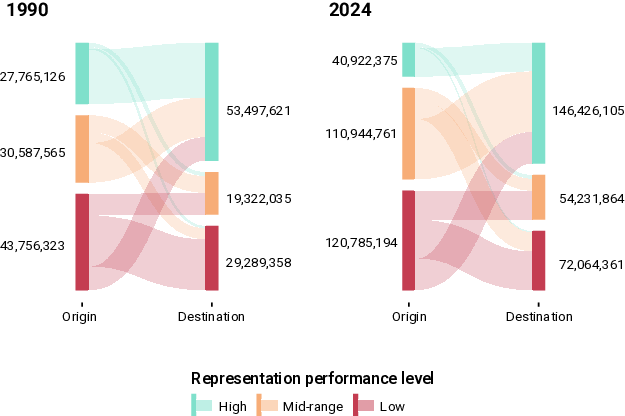

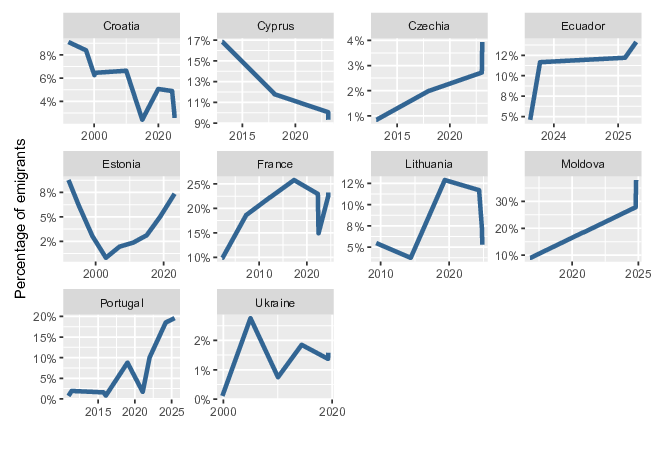

If this age of radical uncertainty is visible in the data, it is felt in human lives. This is certainly true with respect to where people live and what it means for them to live there. More than 300 million people now reside outside the country of their birth, a figure that has tripled since the 1970s, modestly outpacing total population growth. The political inclusion or exclusion of these people in their countries of citizenship reflects important questions—both philosophical and practical—about national belonging and civil rights in a modern democracy. Current migration trends render those questions unavoidable for democracies around the world.

To shed some light on these issues, the second part of this report focuses on the topic of voting rights for citizens living abroad. Leveraging our Institute’s global expertise at the nexus of electoral processes and democracy assessment, the report finds that expanding political participation—such as through effective enfranchisement of out-of-country voters—supports democratic resilience in both the home and host countries. However, the report also documents inconsistencies in data collection and vote administration for out-of-country electorates, calling attention to the need for further research and refinement of electoral mechanisms for this growing group of eligible voters.

Amid all the changes and challenges in the world, our Institute must constantly evaluate whether our indicators and analysis reflect the full spectrum of democratic principles. As I write this preface, the heart-wrenching crisis in Gaza continues. In the two years since Hamas’ horrific mass murder and hostage-taking, Israel’s war in Gaza has killed tens of thousands of innocent people, displaced most of the population, and destroyed nearly every livelihood. Israel is a mid-to-high performing democracy across all our categories, albeit one that has, like many others, suffered some recent declines. That is what this report shows. What the report does not show—what our current methodology cannot show—is that Israel’s war and occupation represent a systematic and brutal assault on Rights, Representation, Rule of Law and Participation in Palestine. Nor does the report show that, on a daily basis, in broad daylight, the authorities of a democratic nation appear to be perpetrating gross violations of international human rights laws in another jurisdiction, as stated by numerous human rights organizations from around the world, a panel of independent United Nations experts, and the International Court of Justice. Such behaviour debases norms designed to protect the values that lie at the heart of the democratic system. Every country has the right to defend itself, but not at the price of making a mockery of international law and democratic principles. While not unique, the case of Israel raises serious, global questions about what it means to be a democracy, and whether the duties of democracy extend beyond borders. Those questions will not be answered in this report, but our Institute is committed to examining them in the months and years ahead.

International IDEA’s guiding vision is a world in which everyone lives in inclusive and resilient democracies. This report is about how democracy is faring to this end—and what might be done, in ways big and small, to bring us closer.

Dr Kevin Casas-Zamora

Secretary-General, International IDEA

The findings of the 2025 Global State of Democracy (GSoD) report underscore the current global climate of radical uncertainty, exemplified by political developments in the United States that are shaking long-held assumptions about democratic resilience and multilateralism.

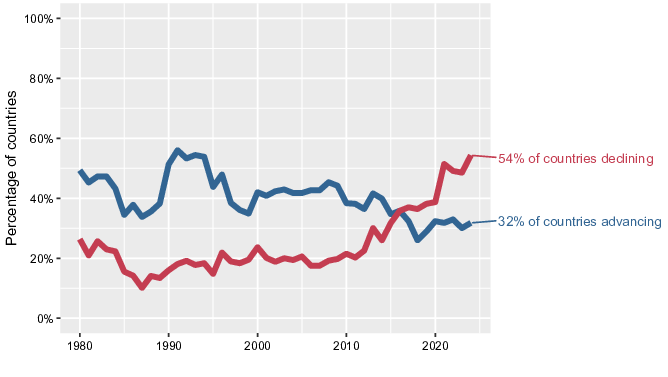

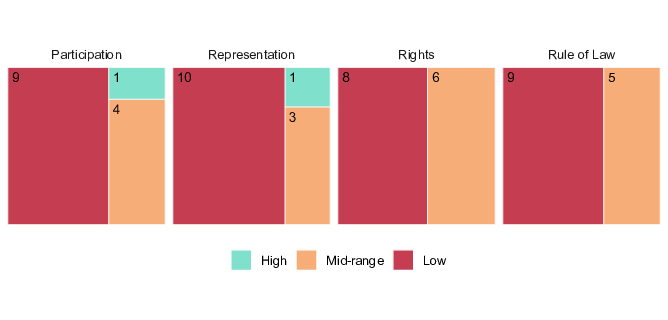

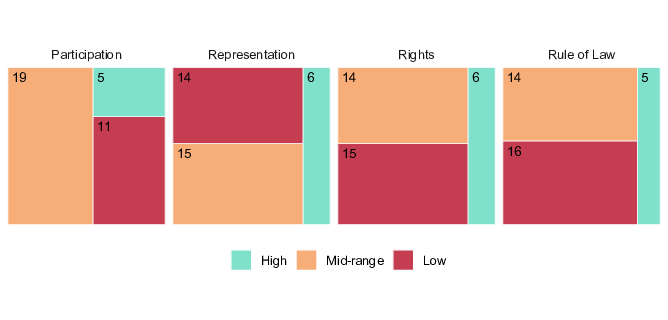

The events in the United States are not happening in a vacuum, as global patterns show that democracy around the world continues to weaken. In 2024, 94 countries—representing 54 per cent of all countries assessed—suffered a decline in at least one factor of democratic performance compared with their own performance five years earlier. In contrast, only 55 countries (32 per cent) advanced in at least one factor over that period.

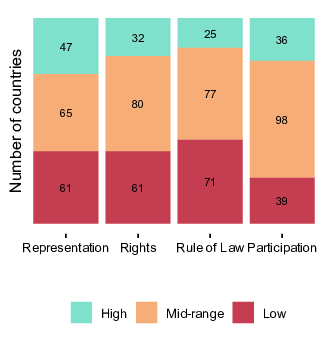

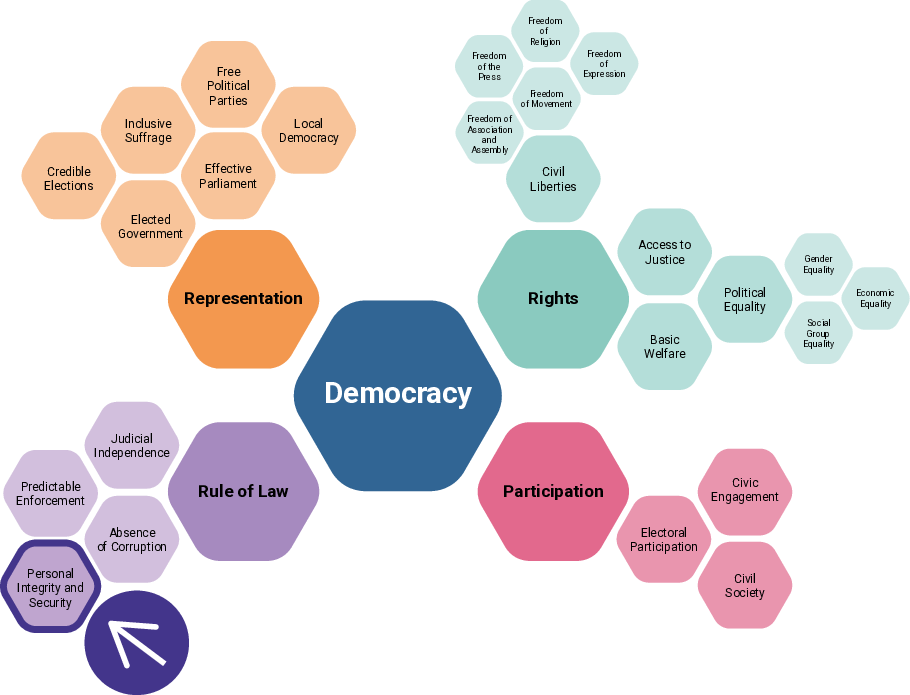

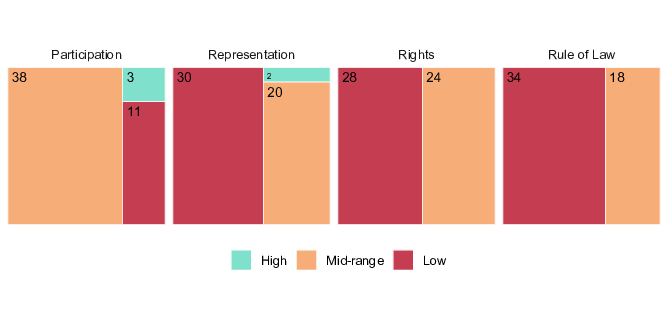

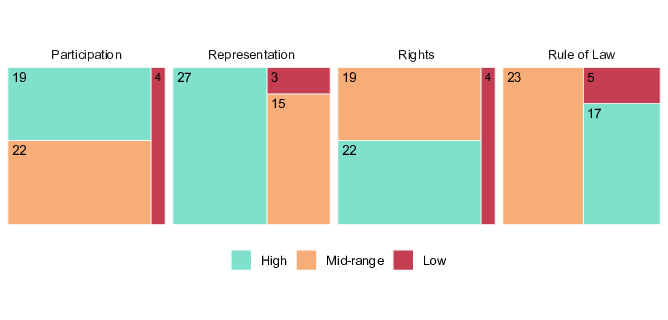

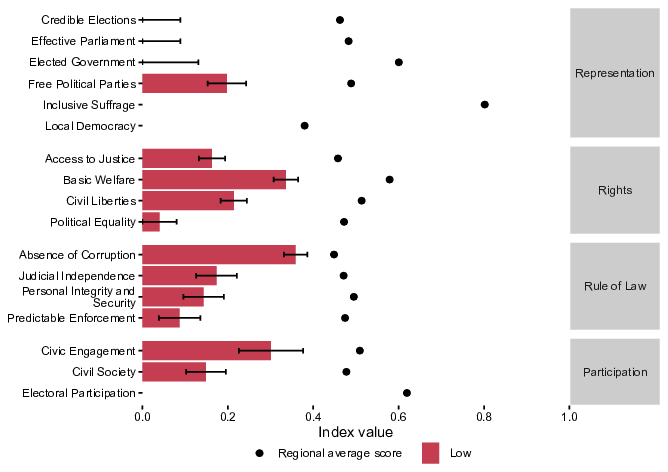

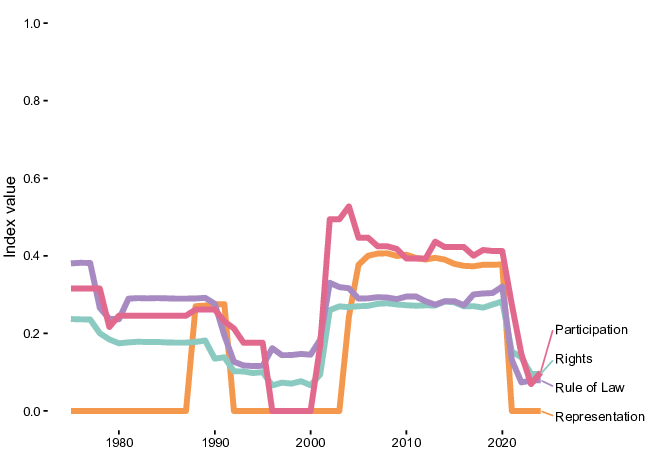

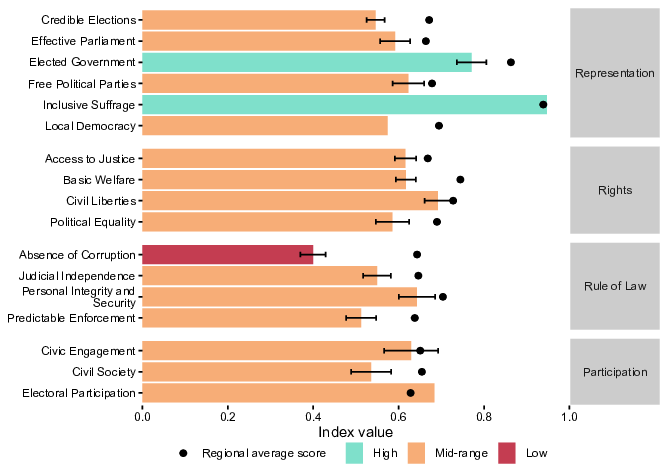

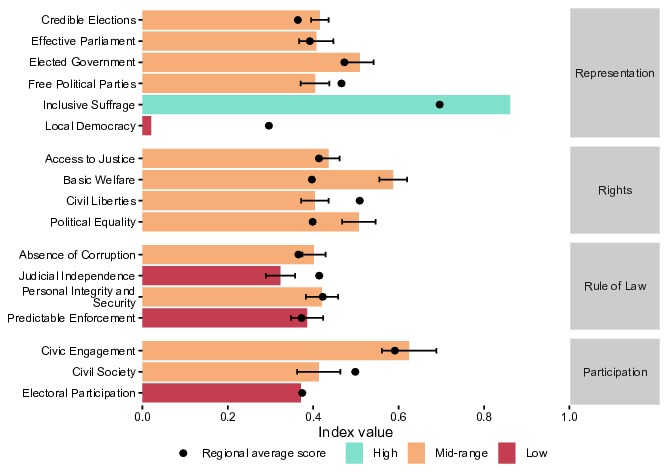

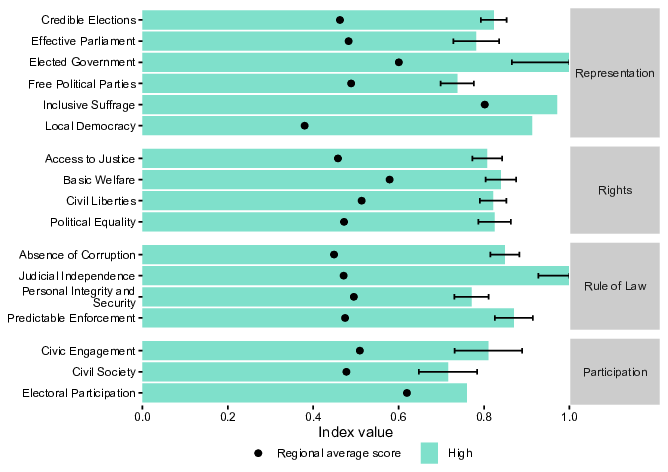

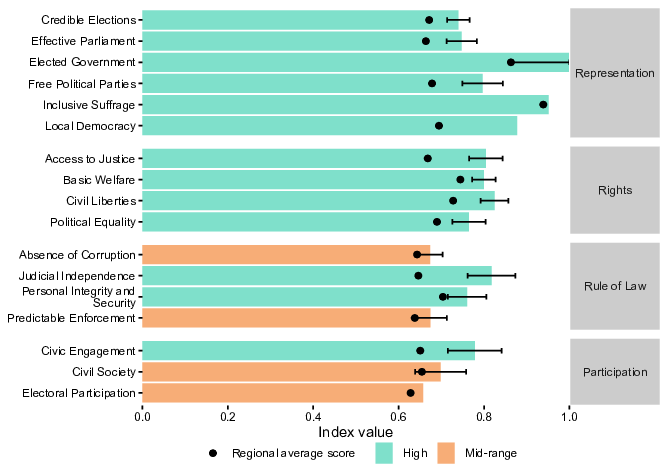

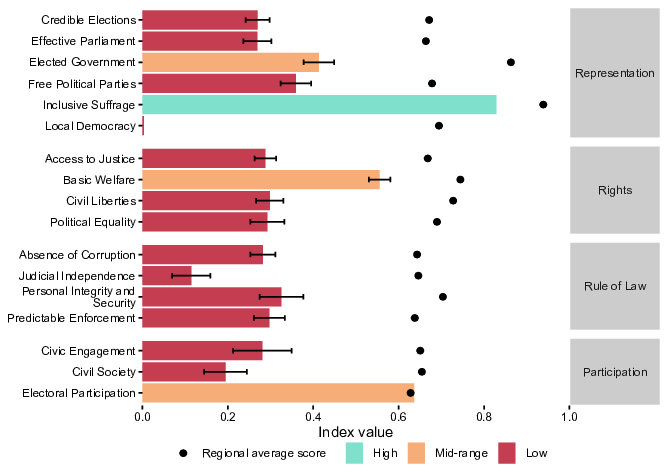

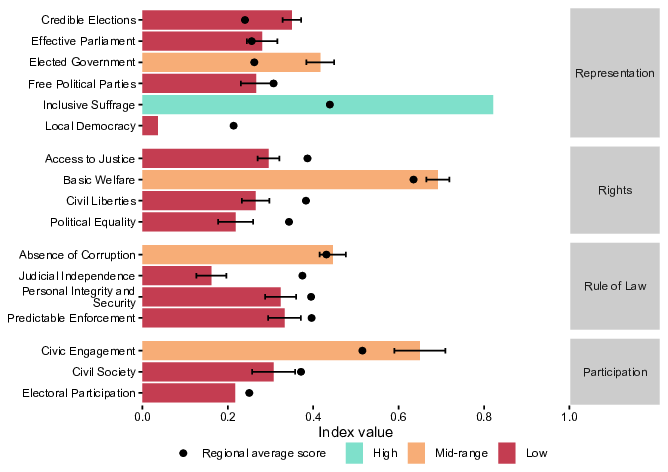

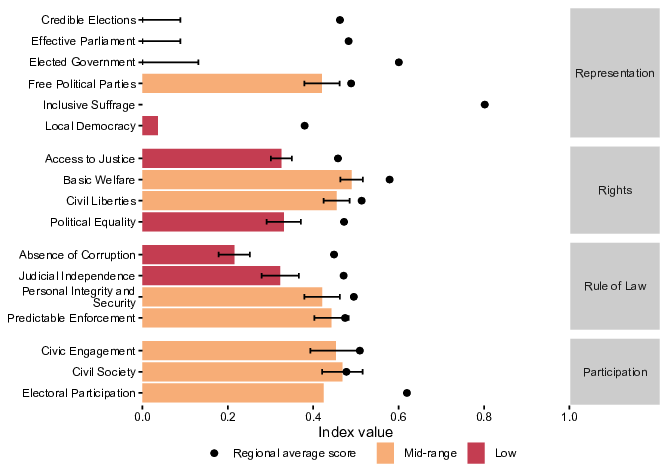

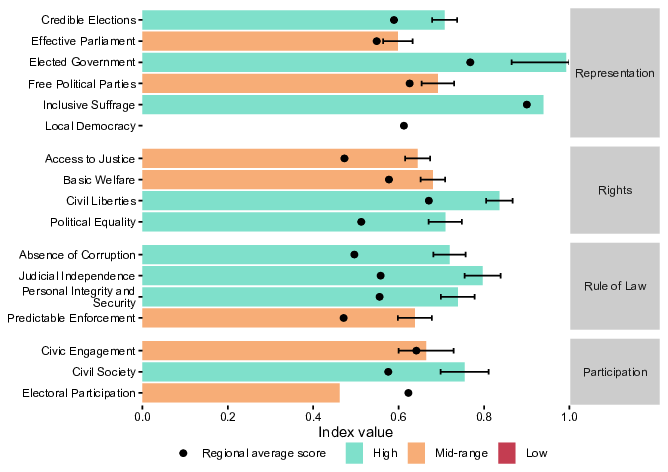

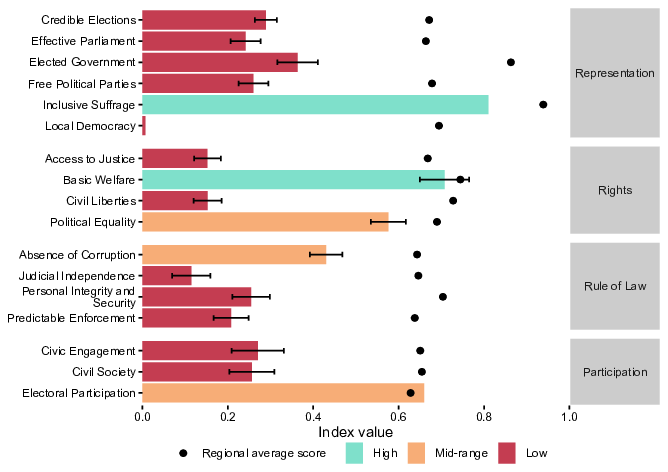

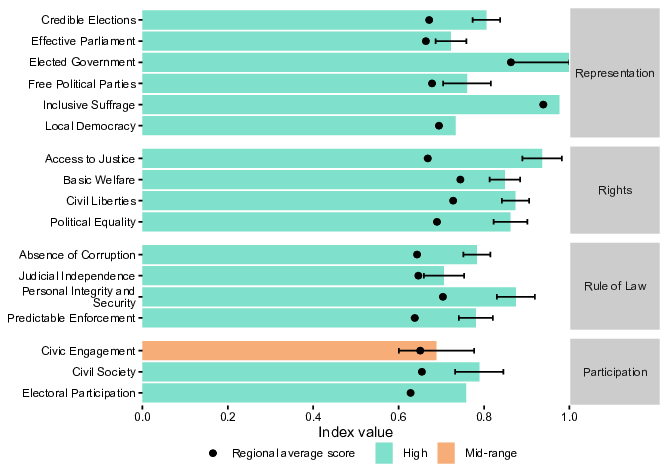

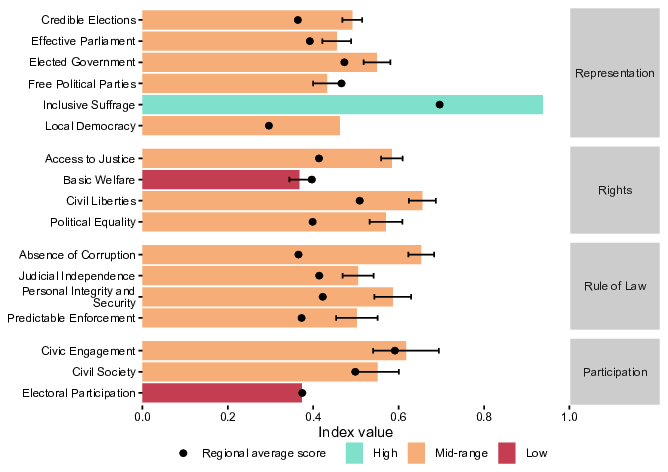

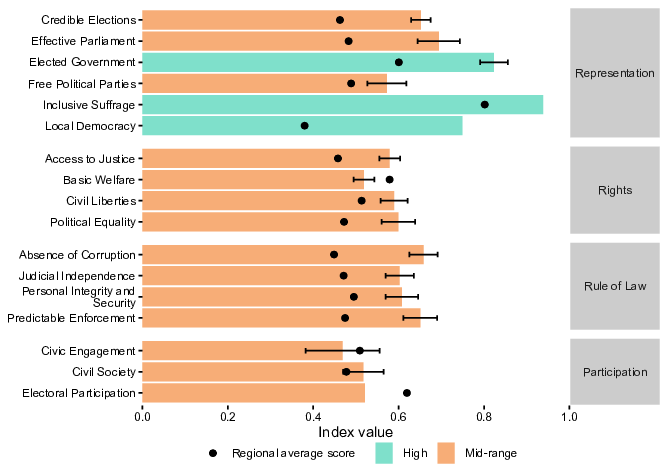

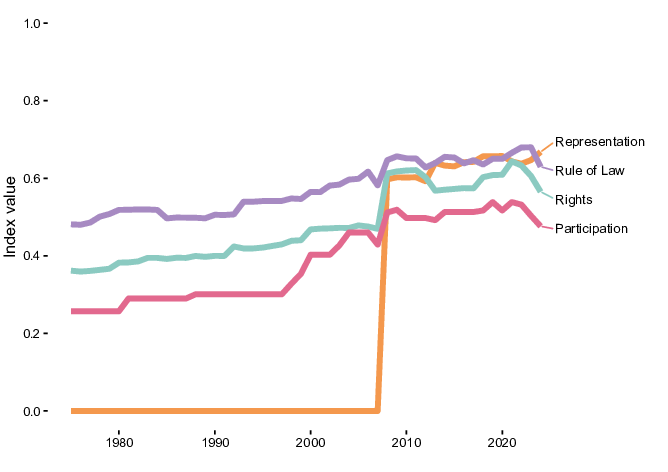

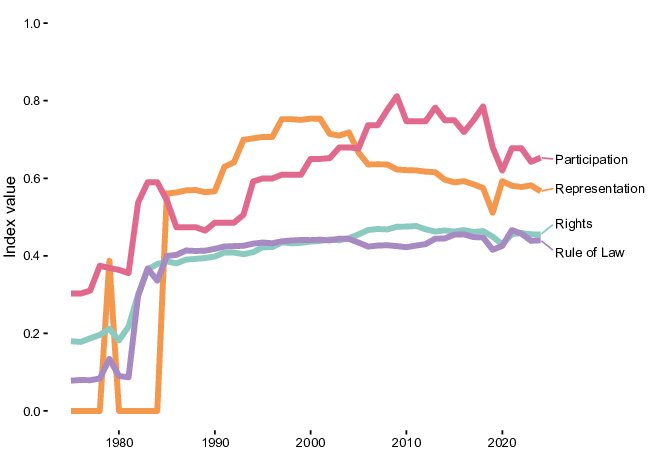

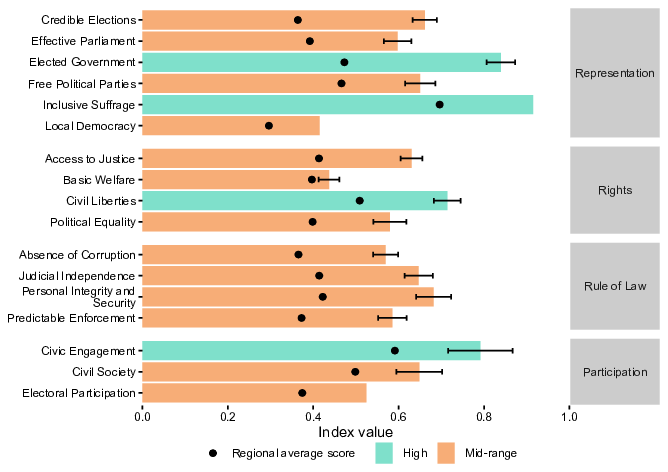

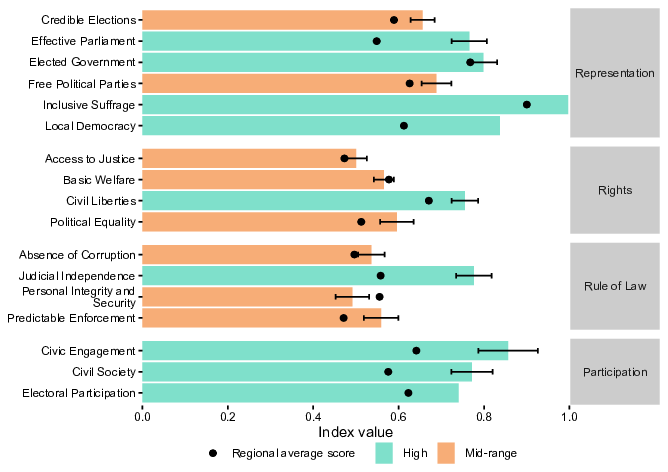

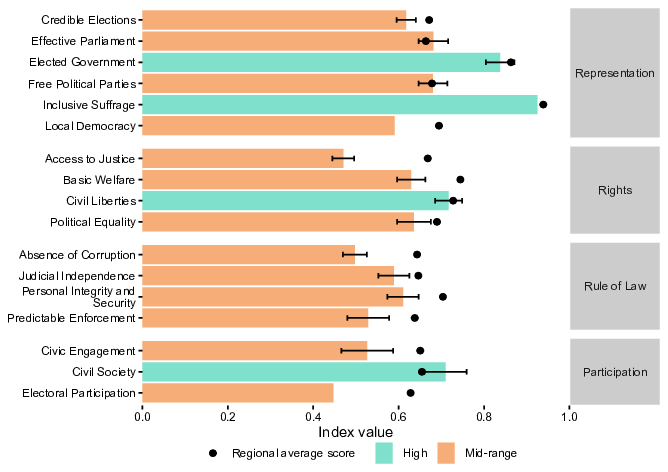

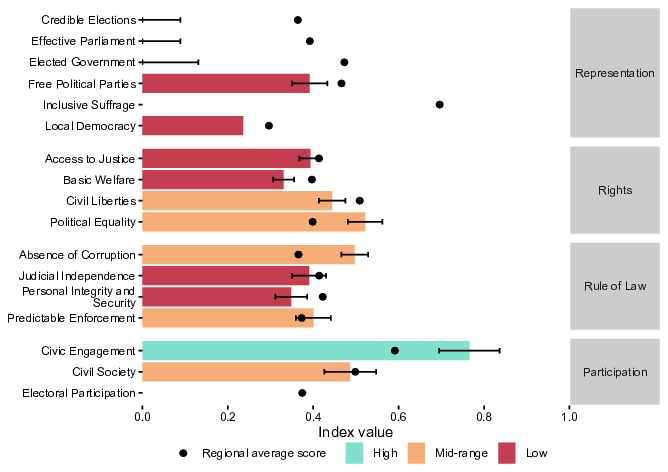

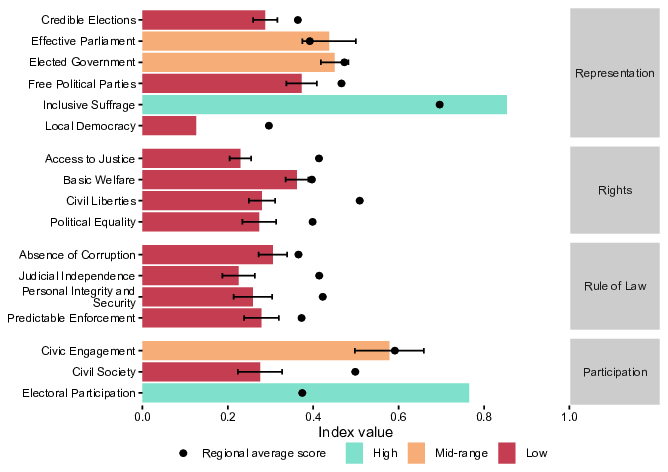

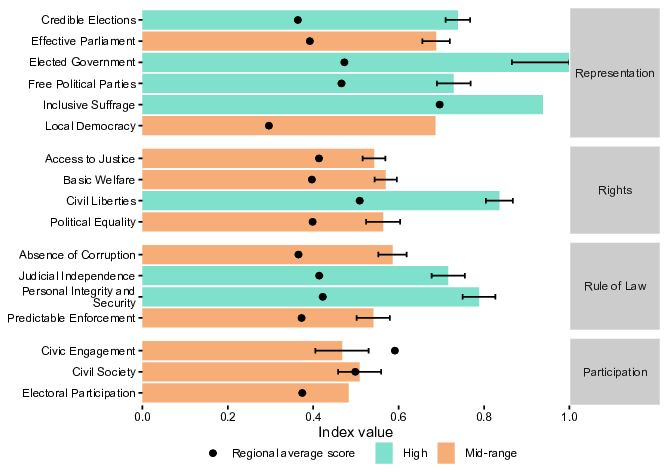

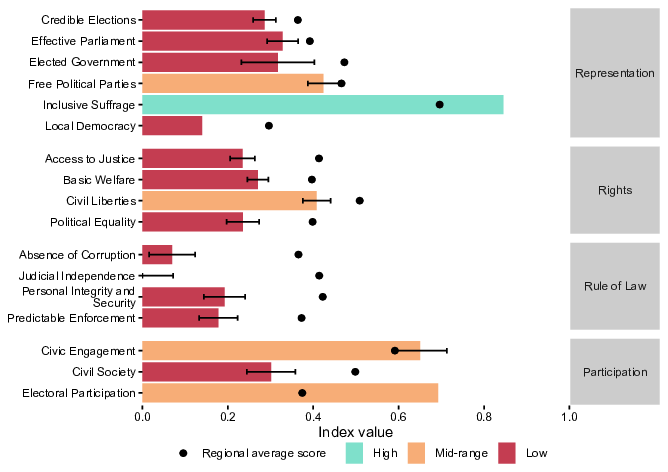

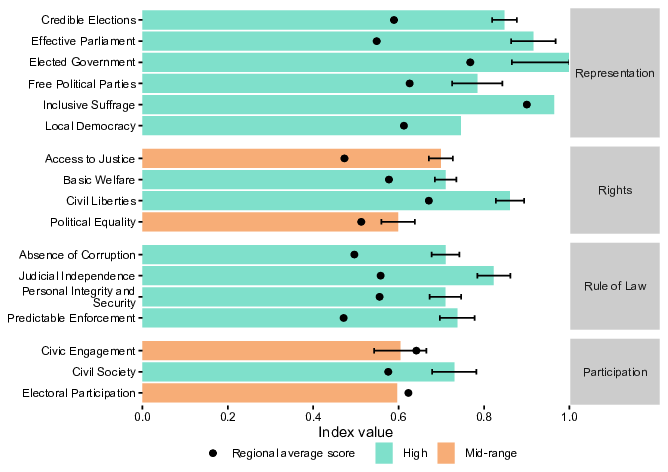

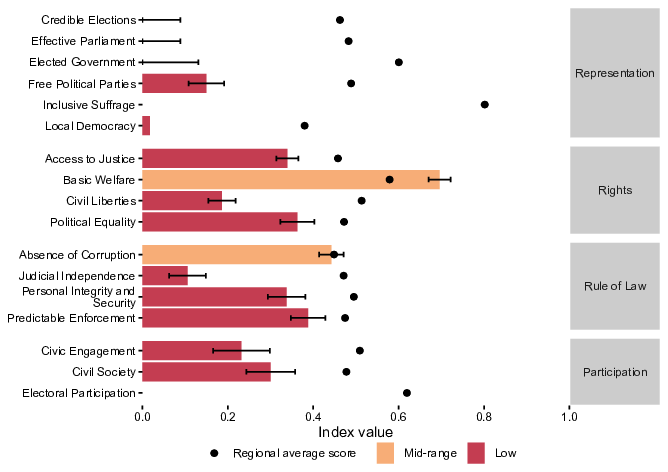

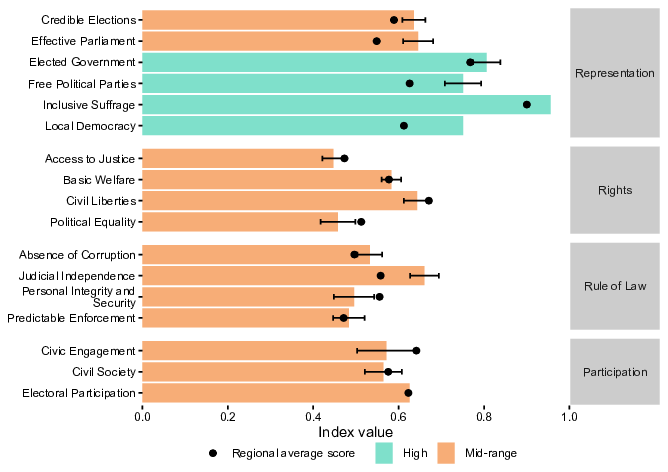

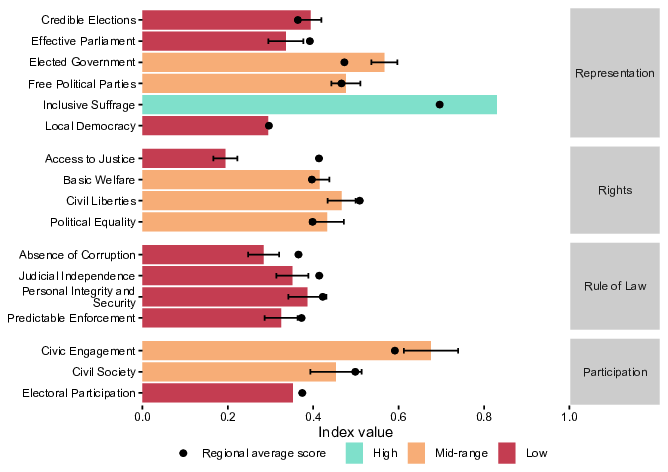

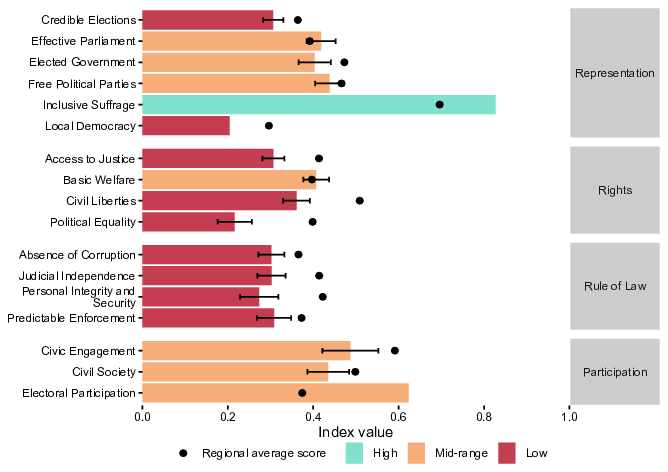

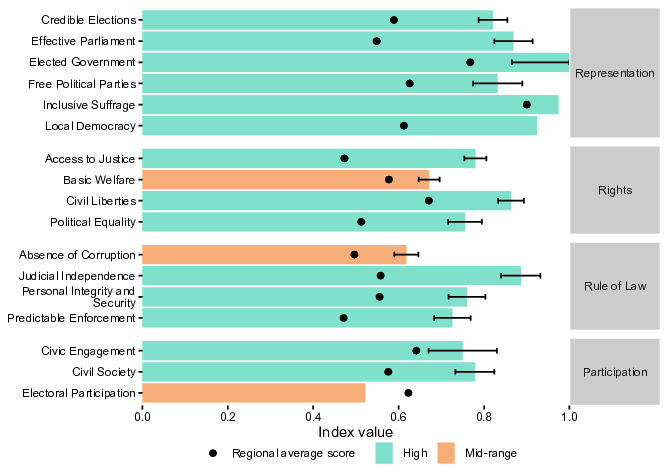

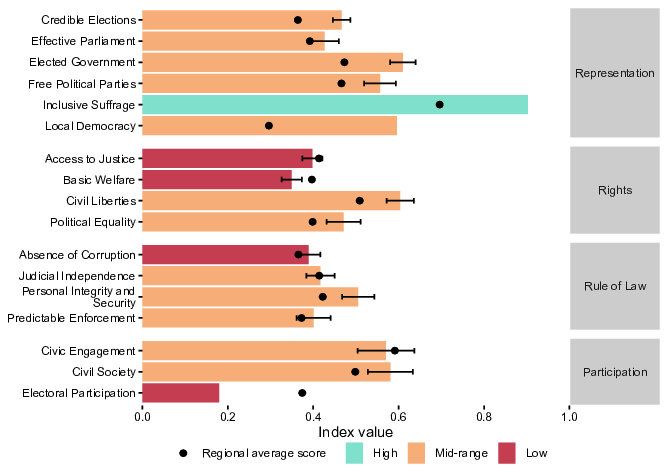

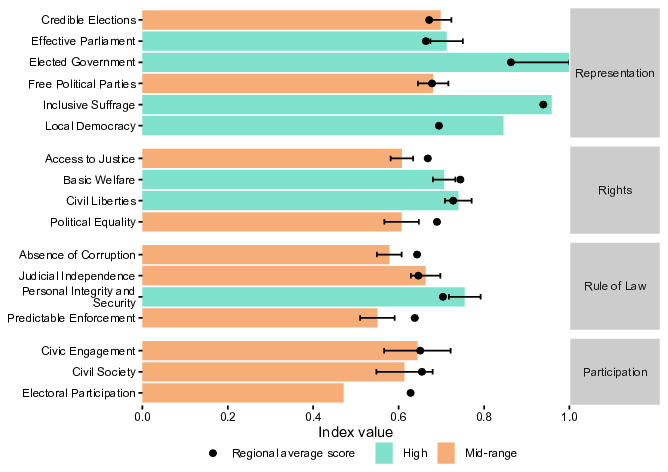

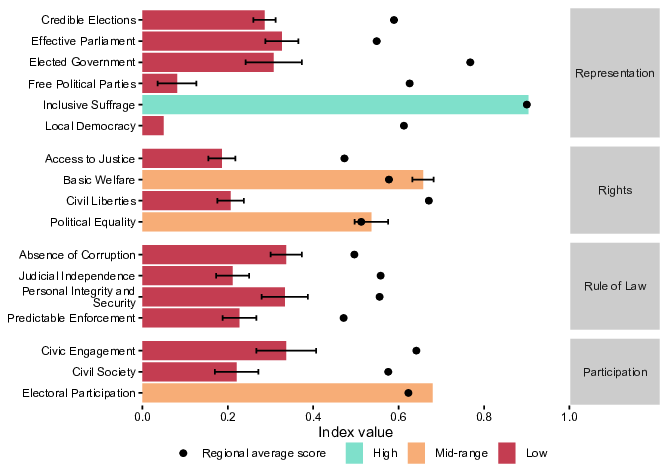

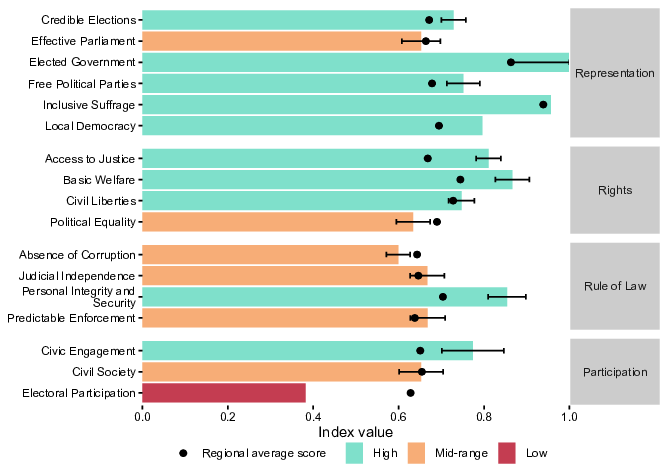

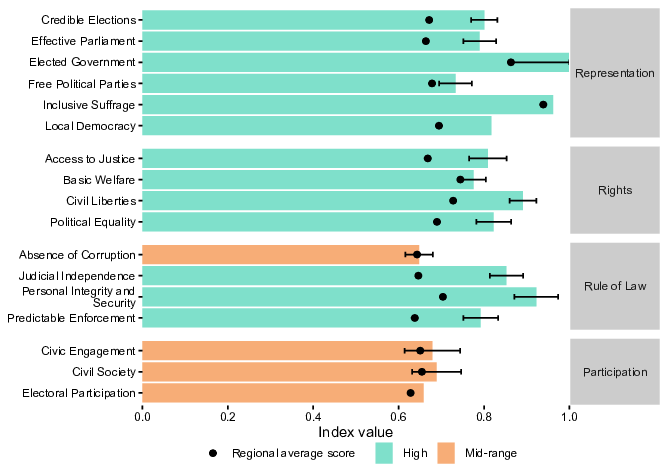

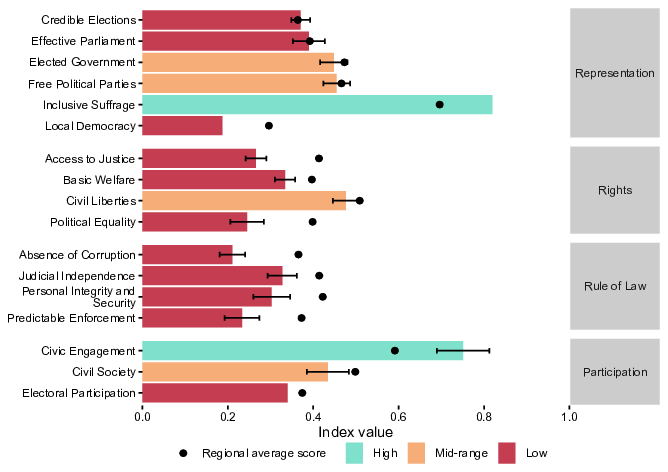

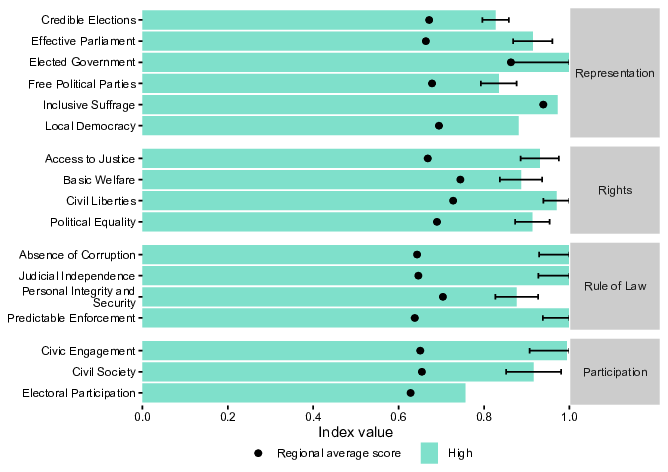

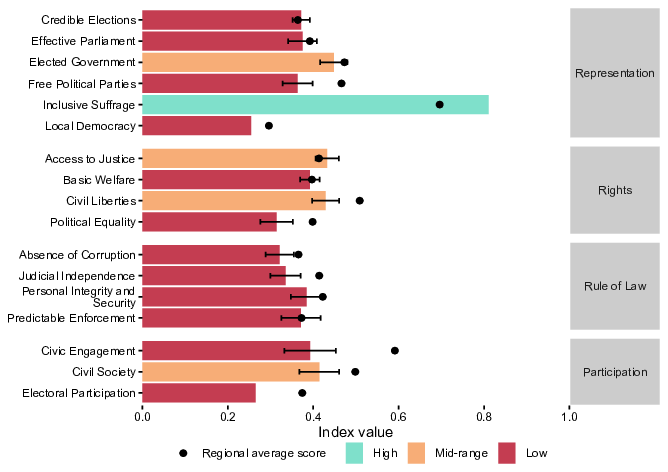

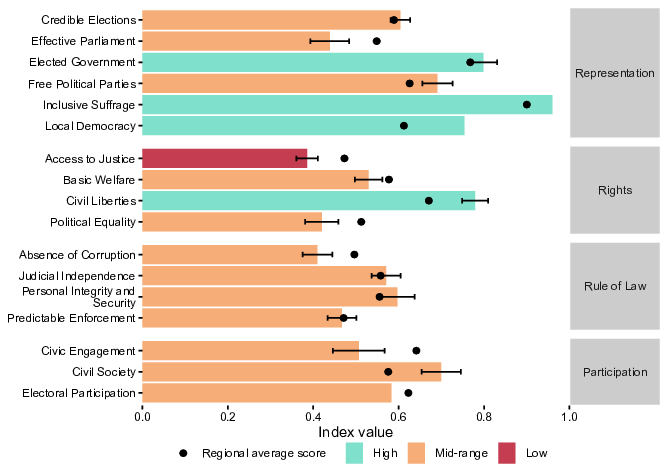

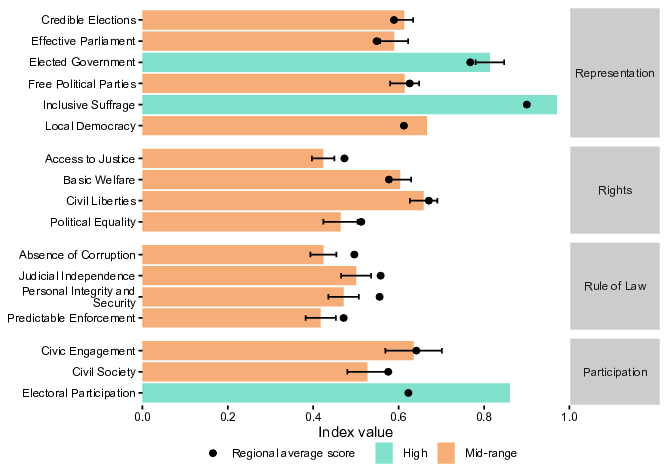

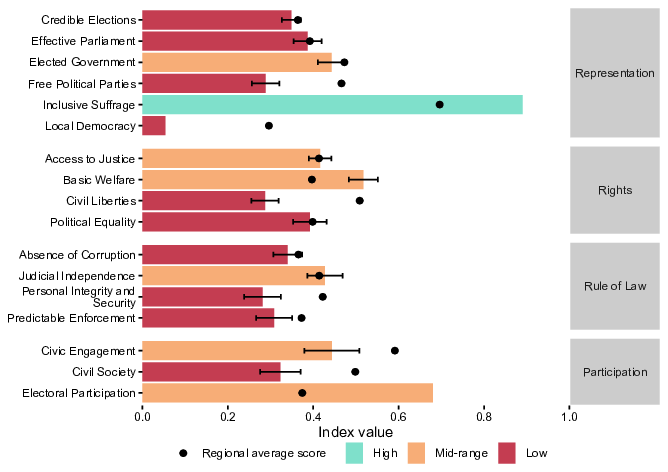

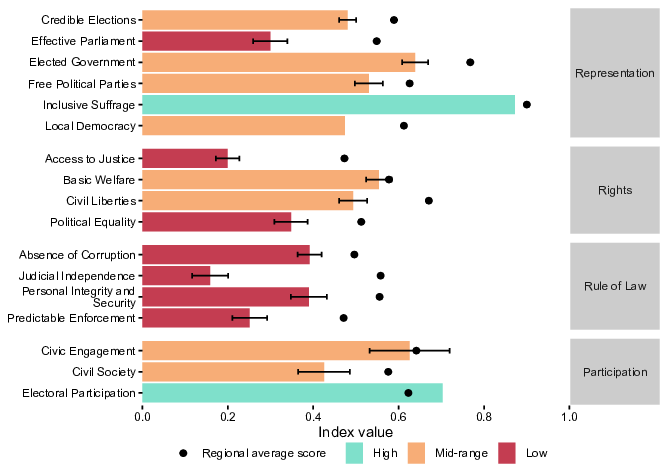

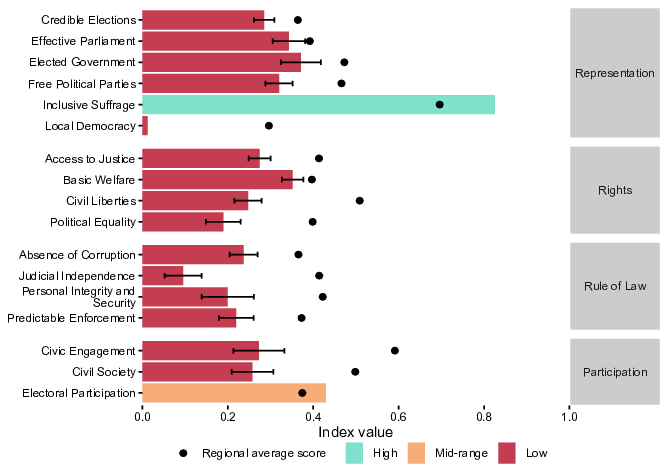

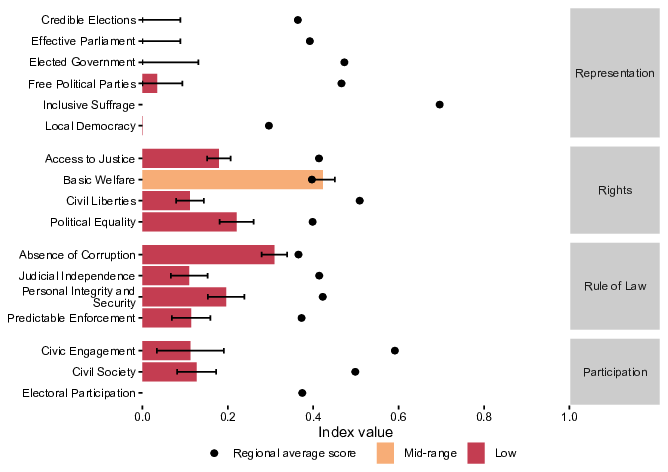

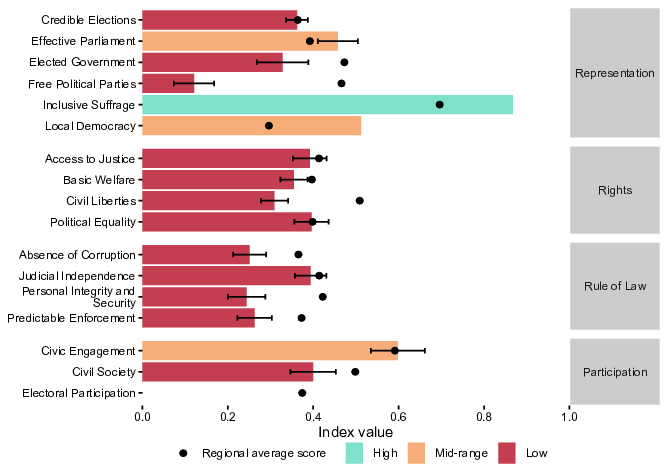

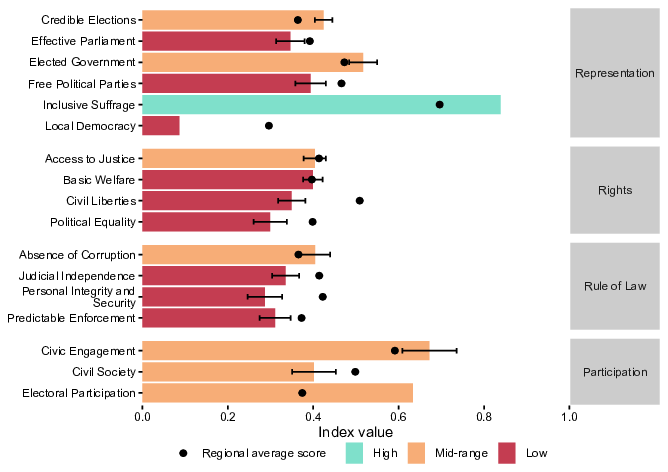

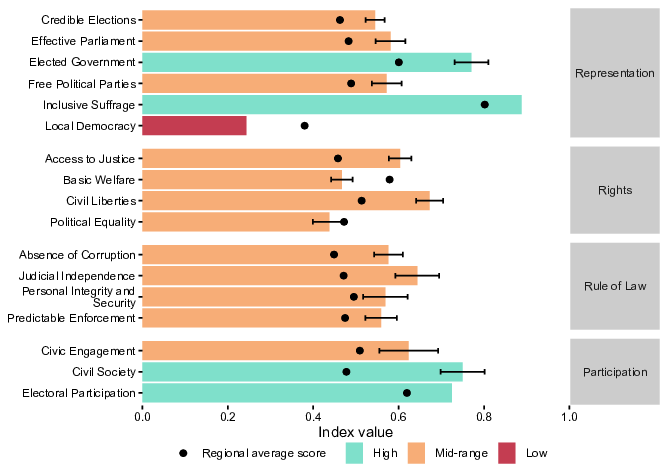

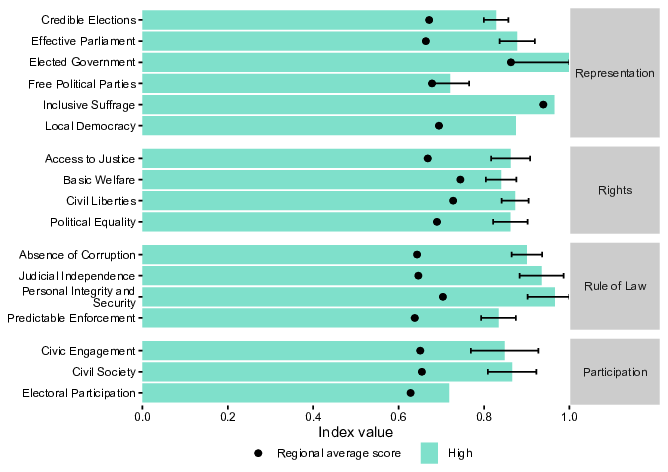

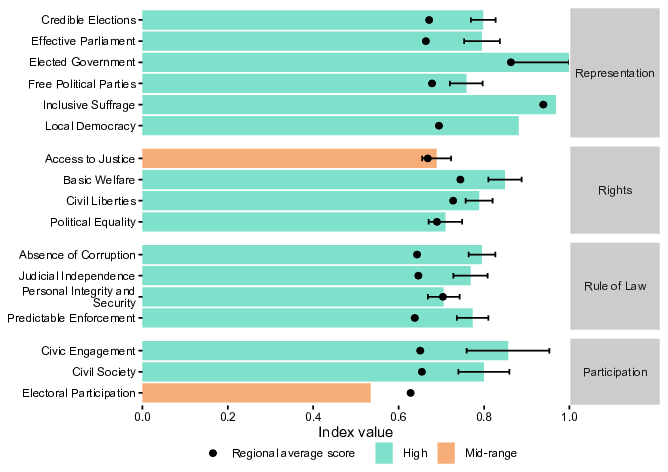

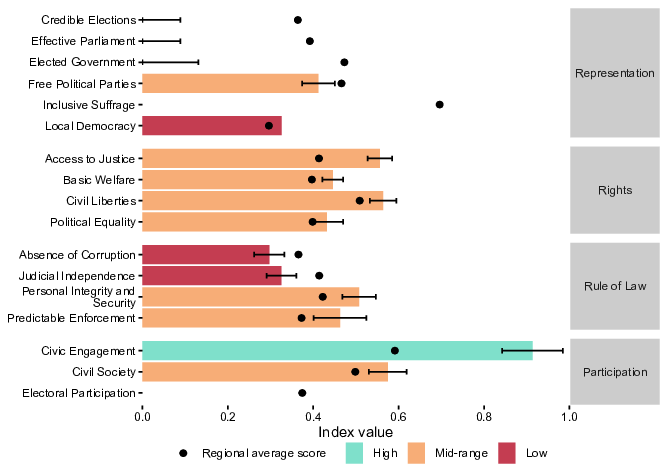

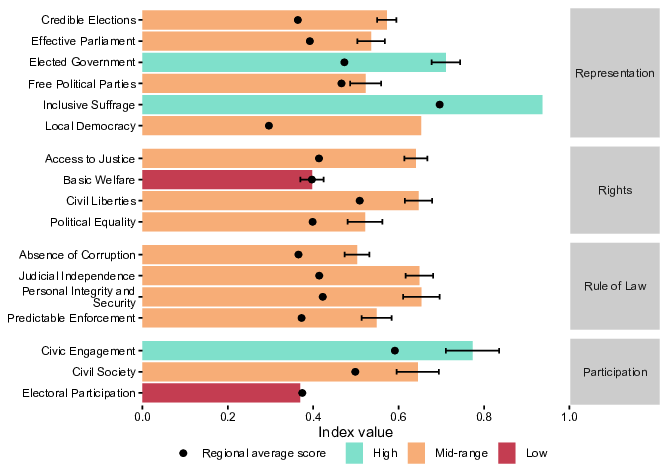

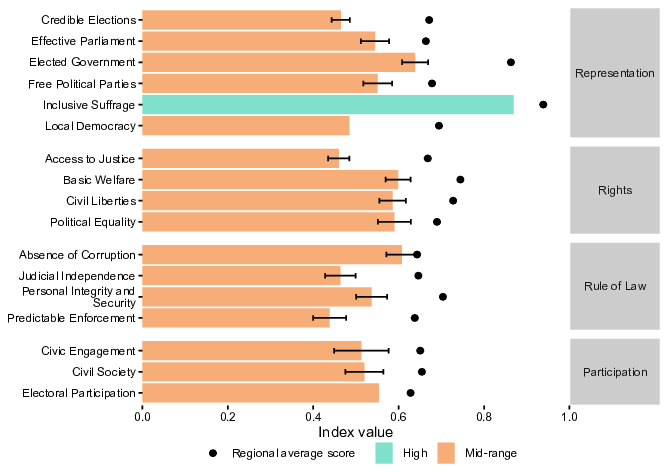

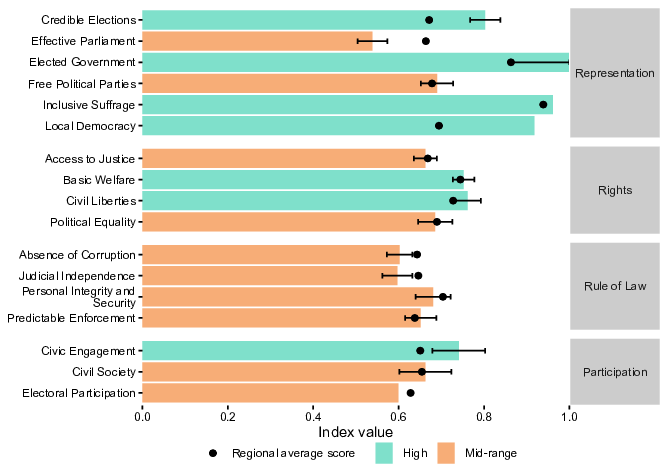

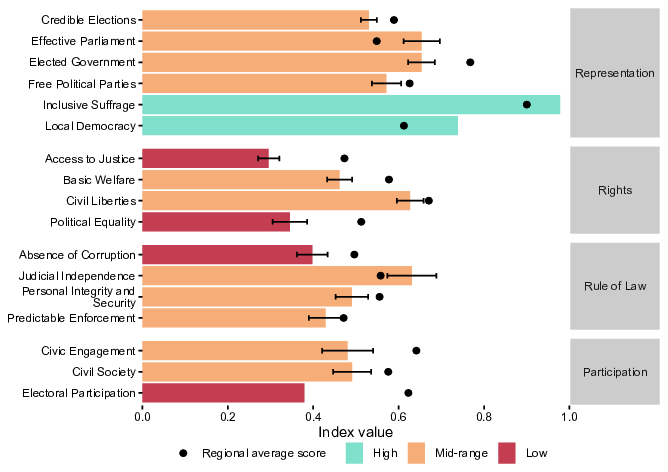

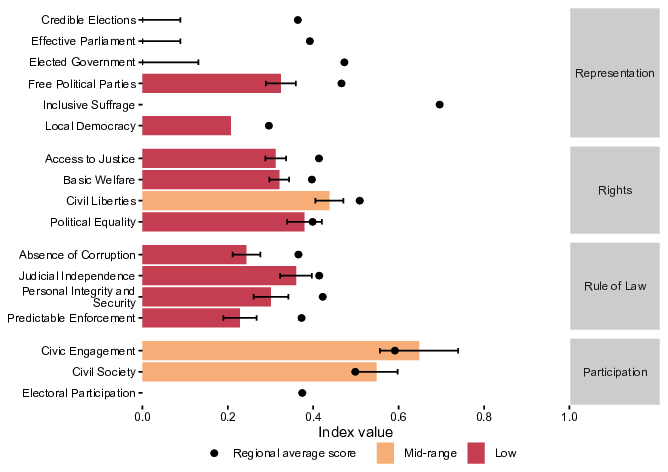

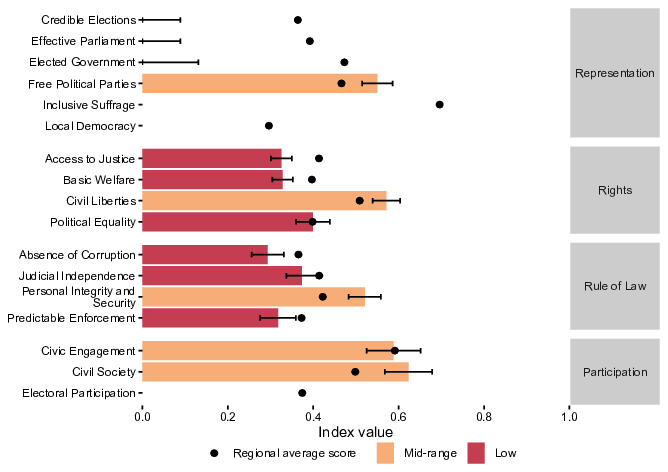

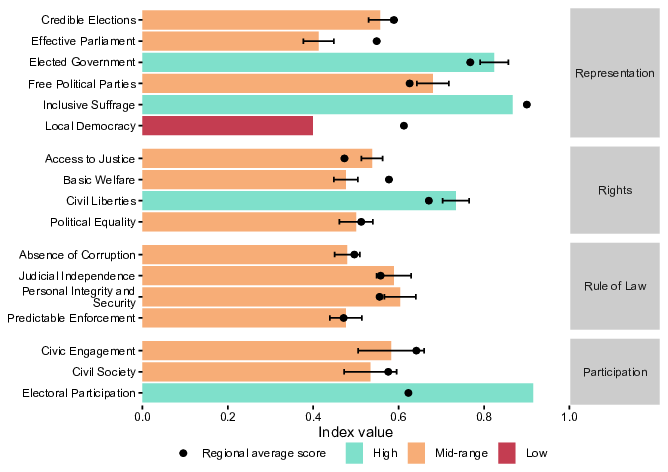

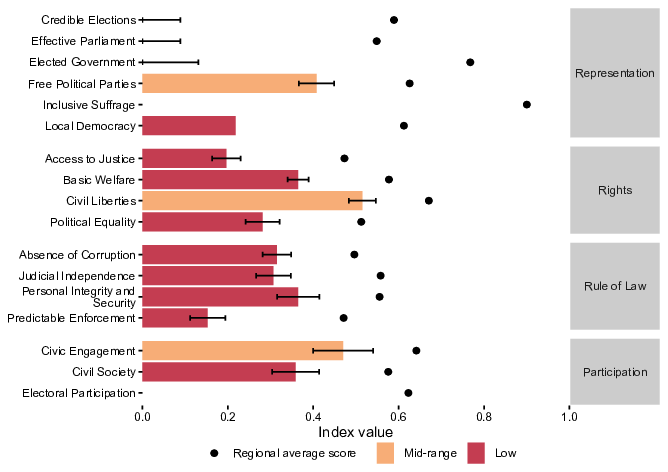

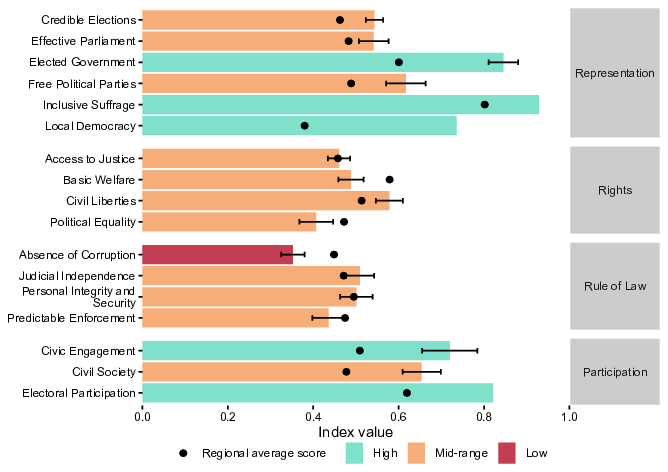

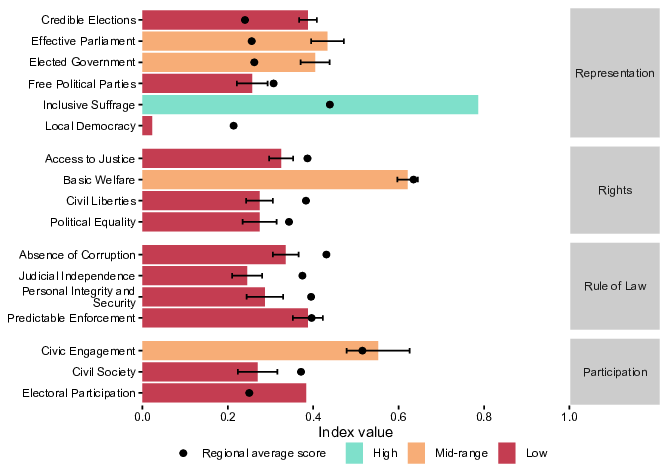

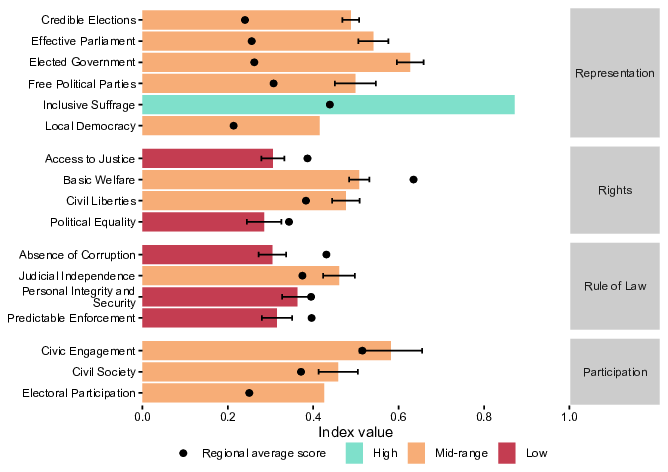

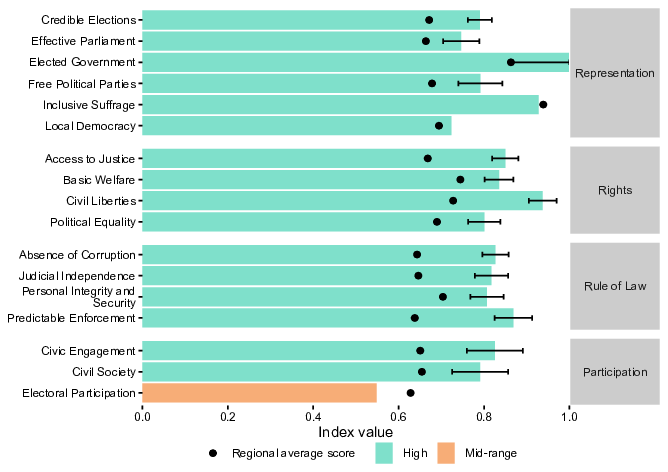

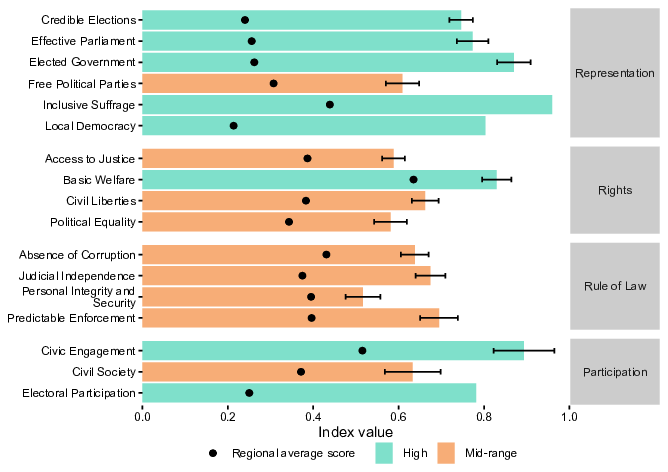

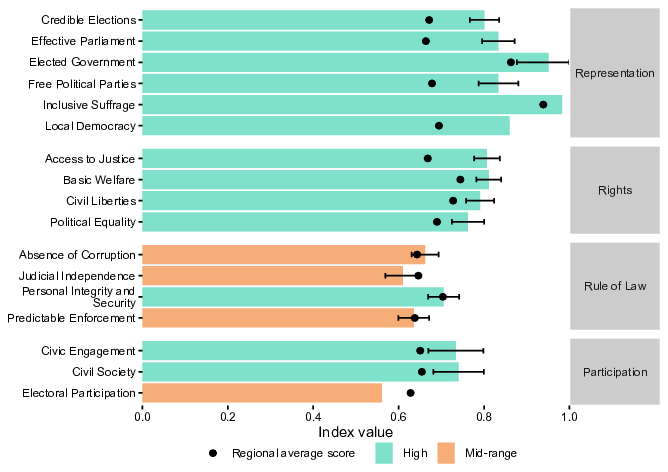

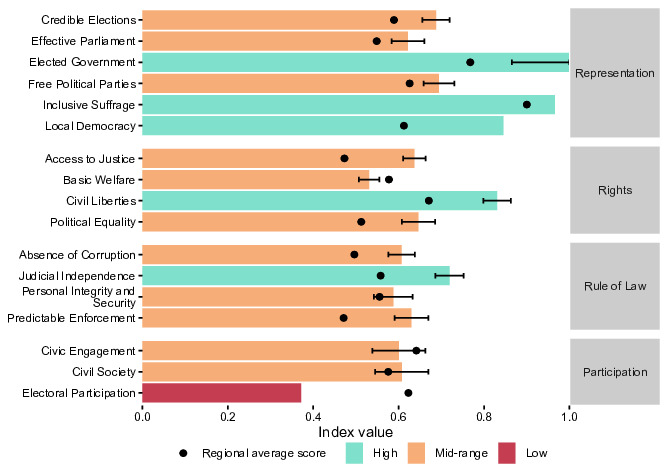

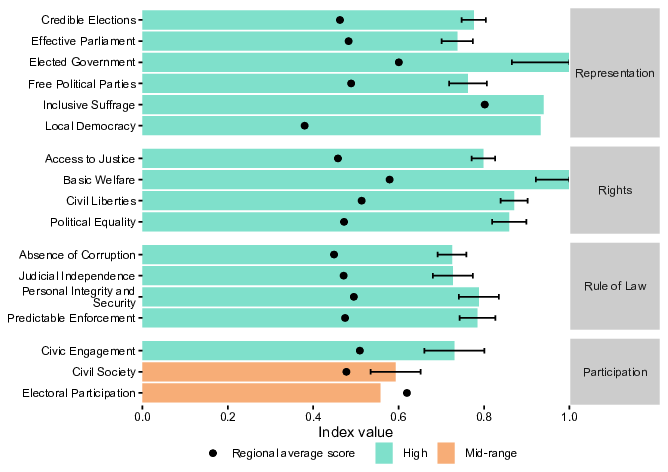

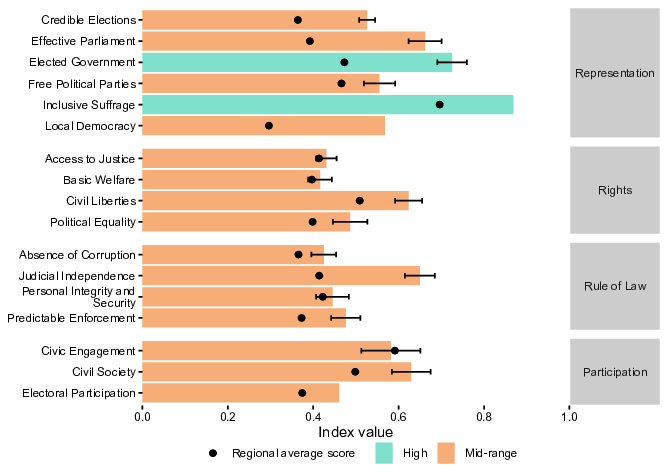

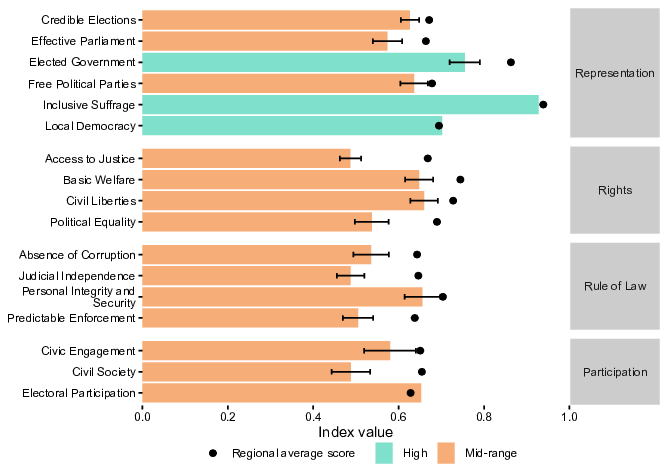

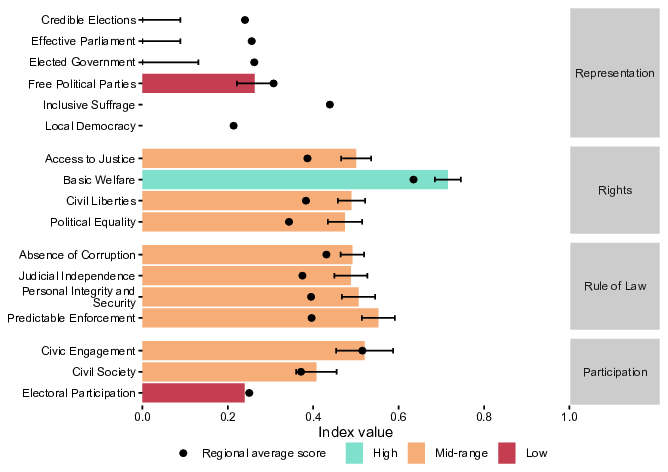

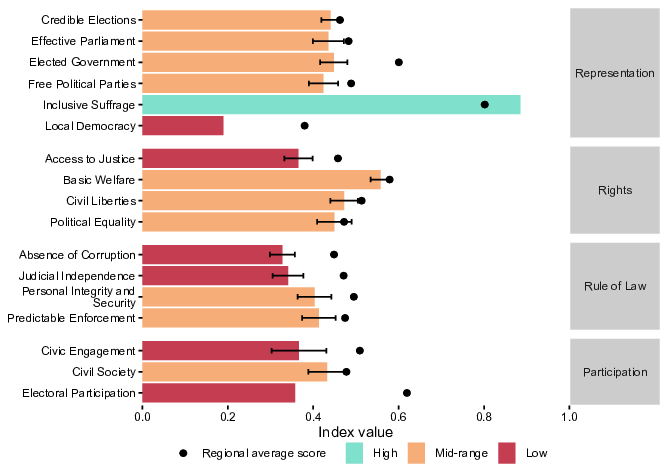

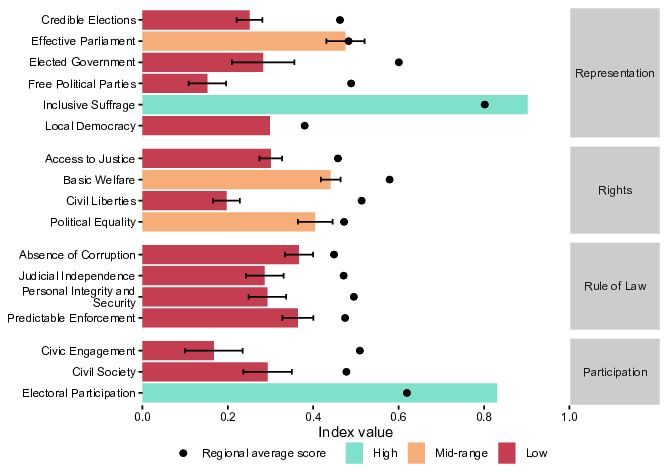

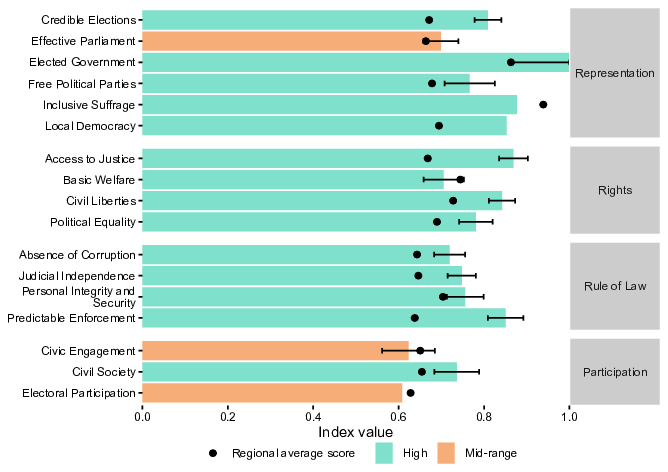

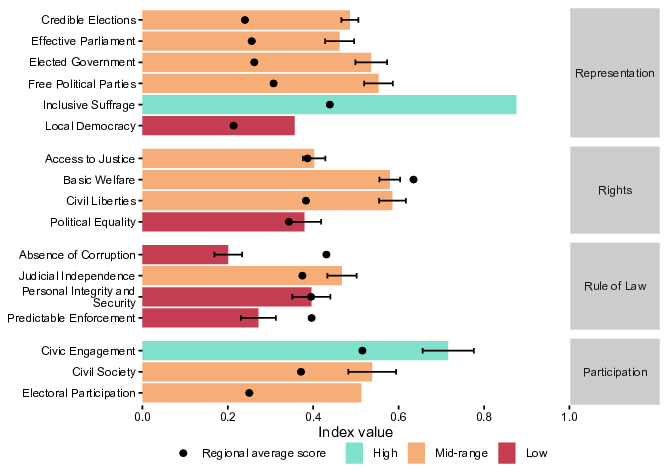

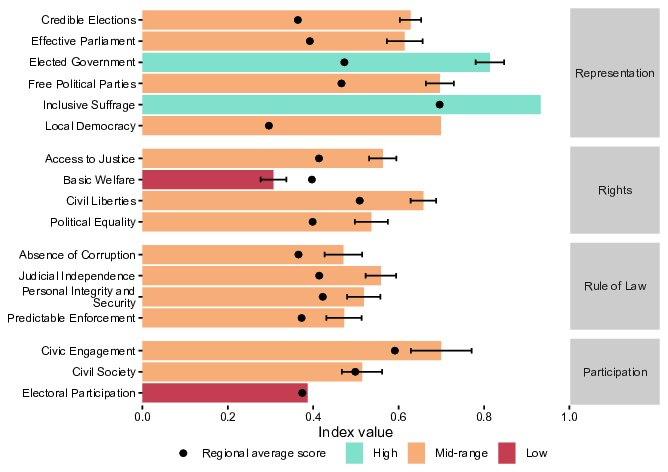

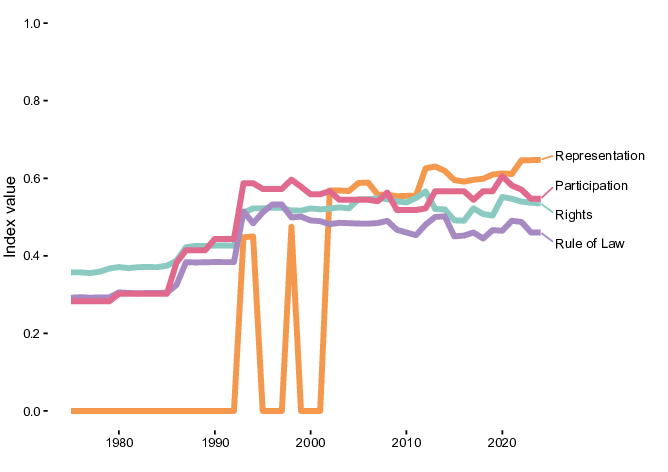

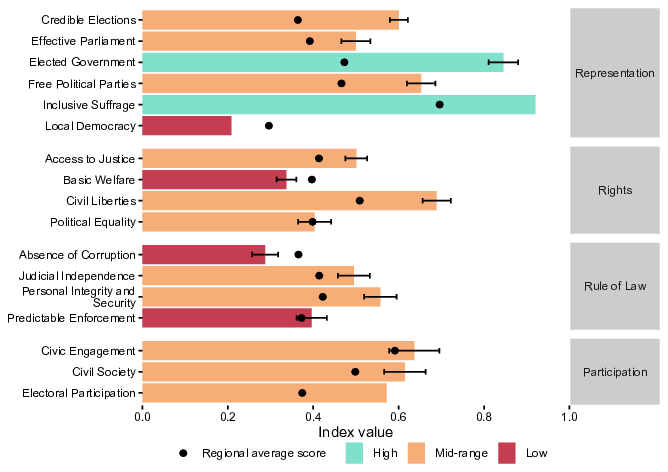

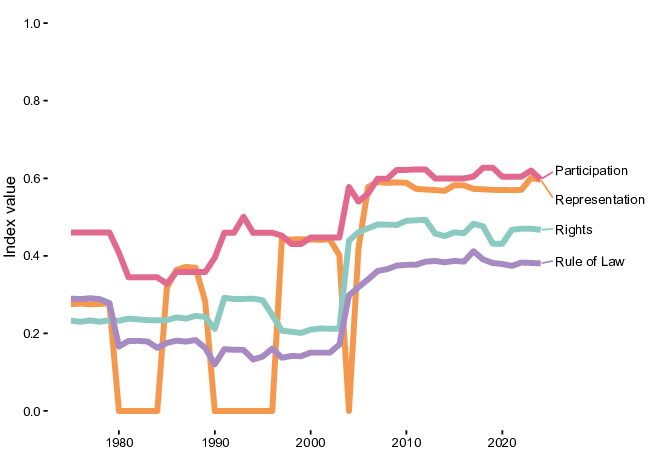

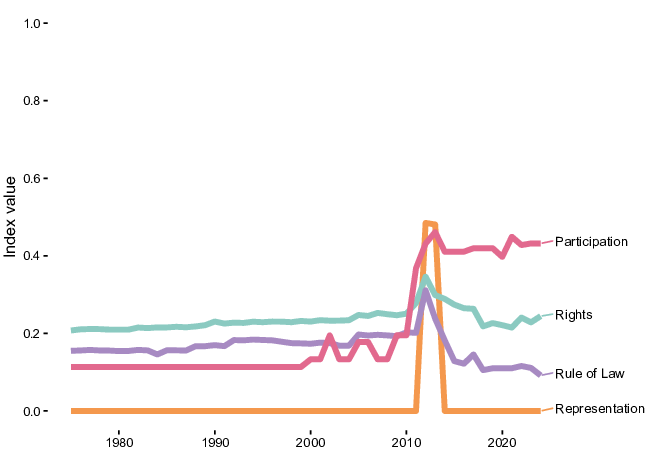

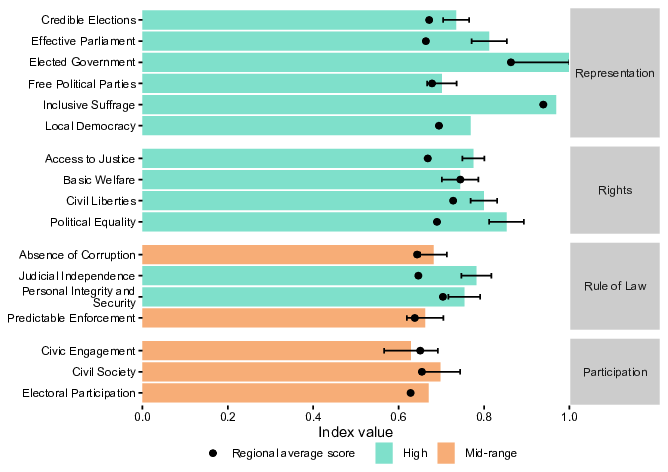

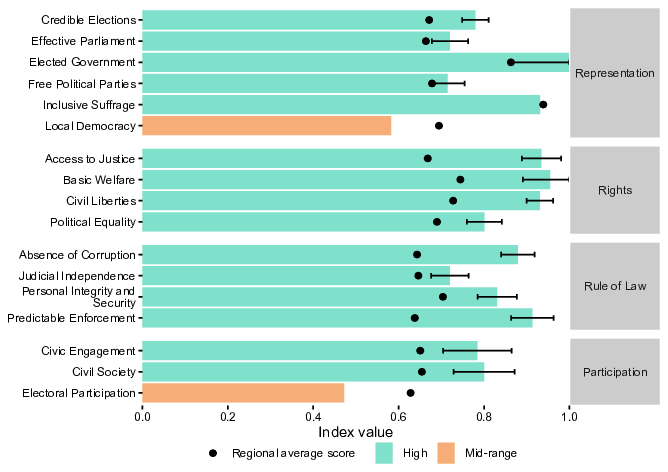

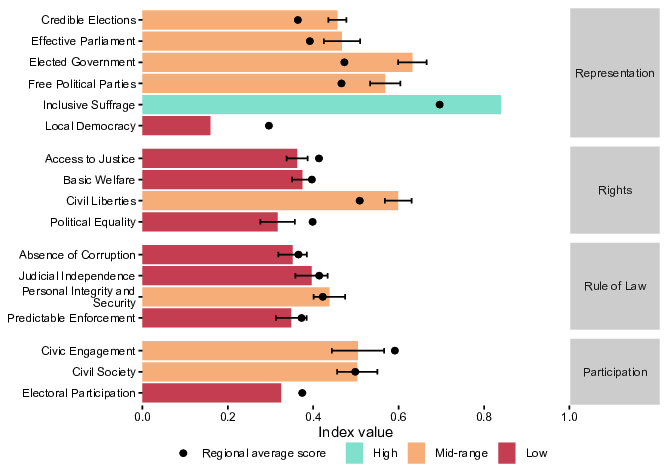

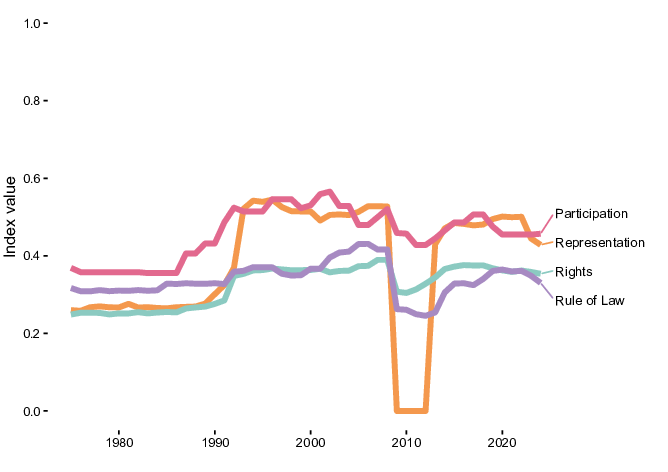

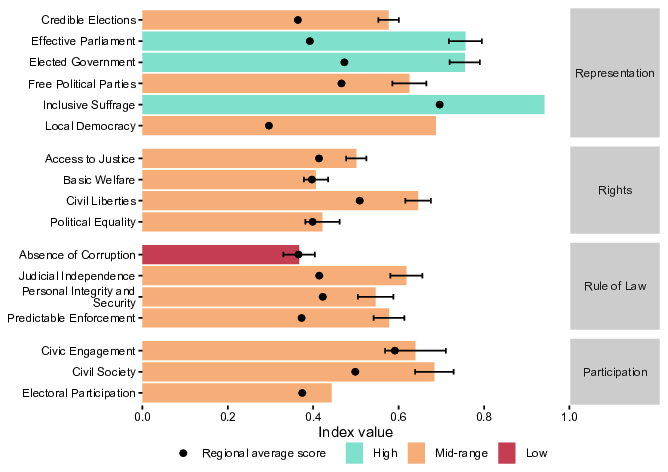

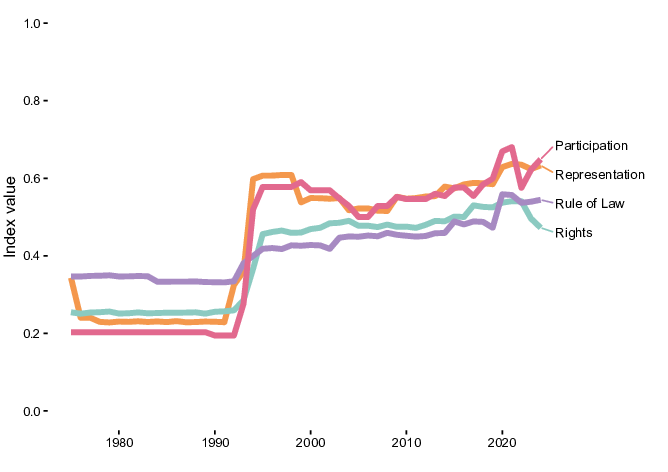

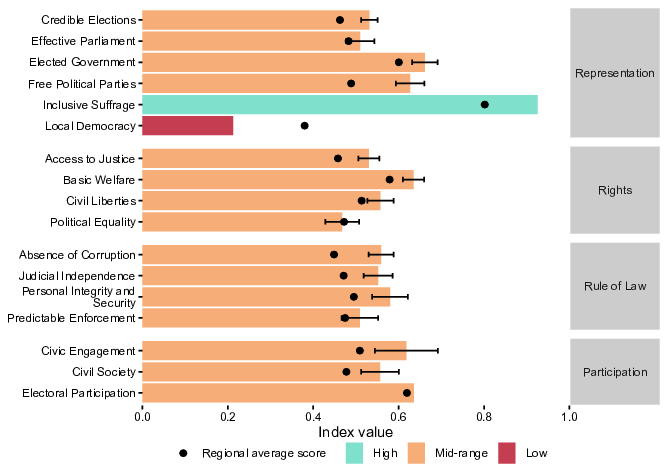

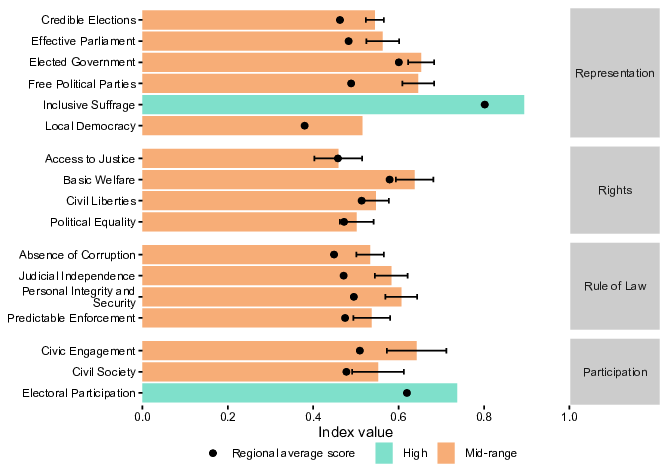

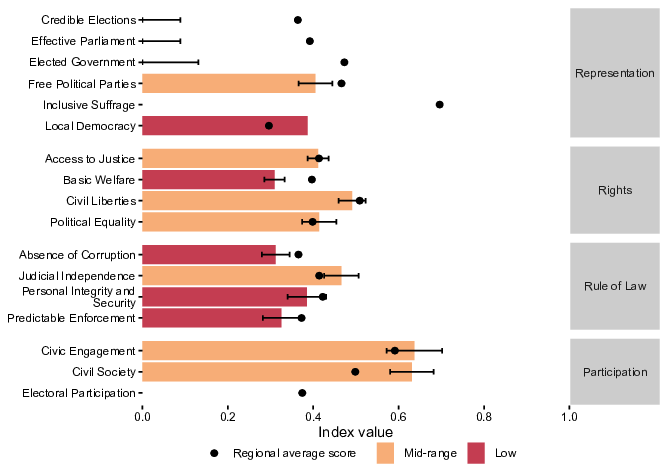

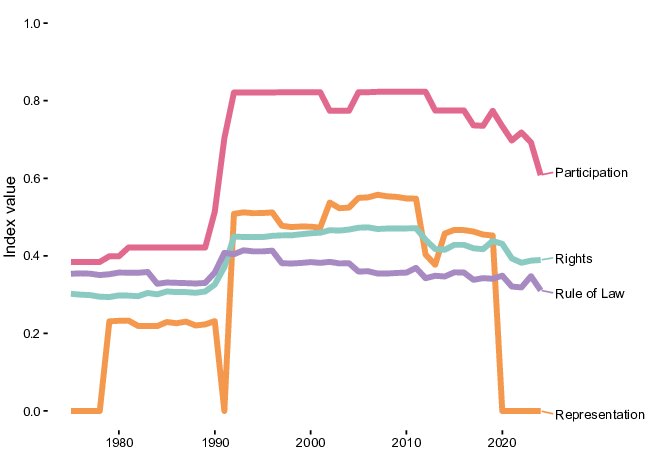

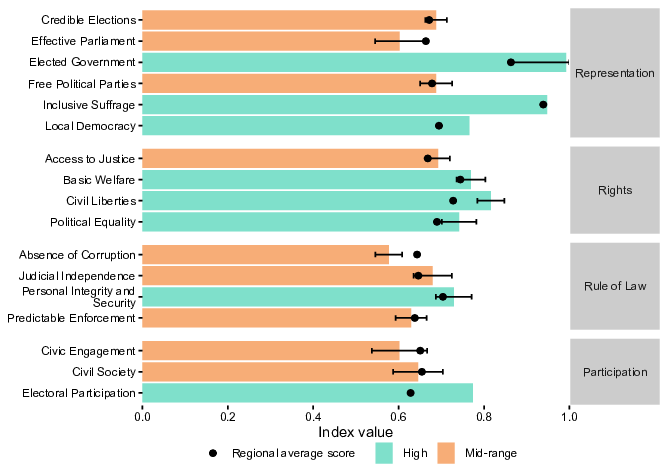

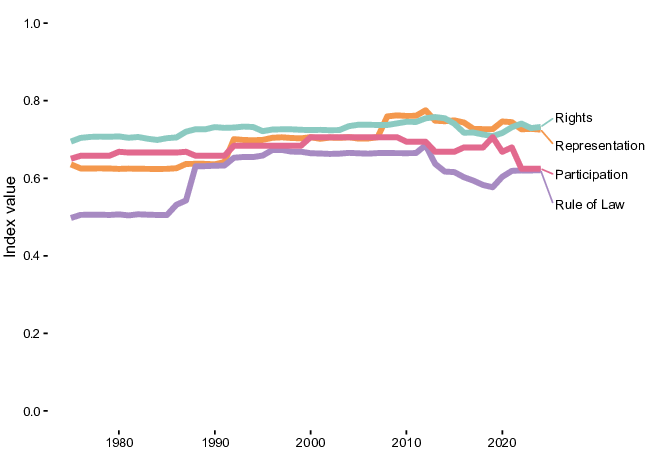

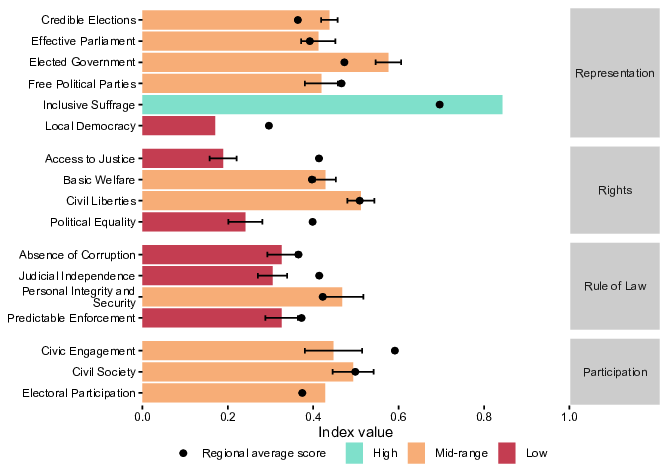

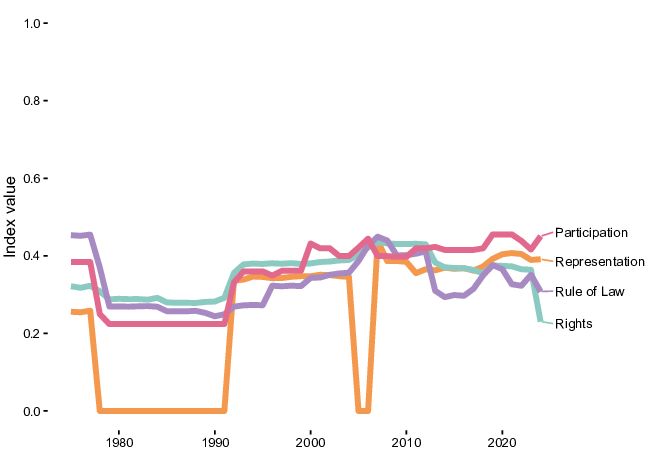

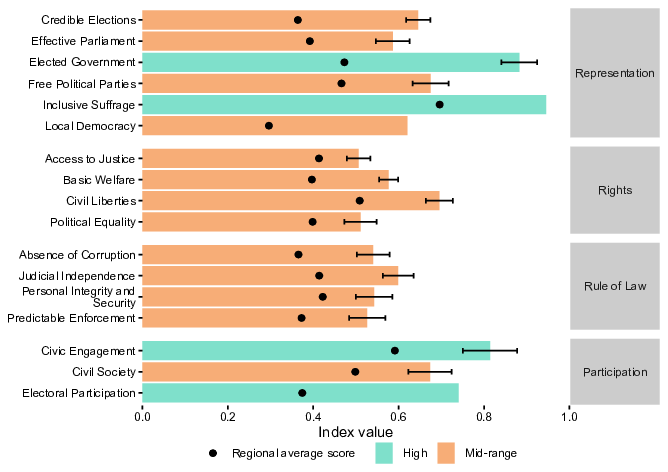

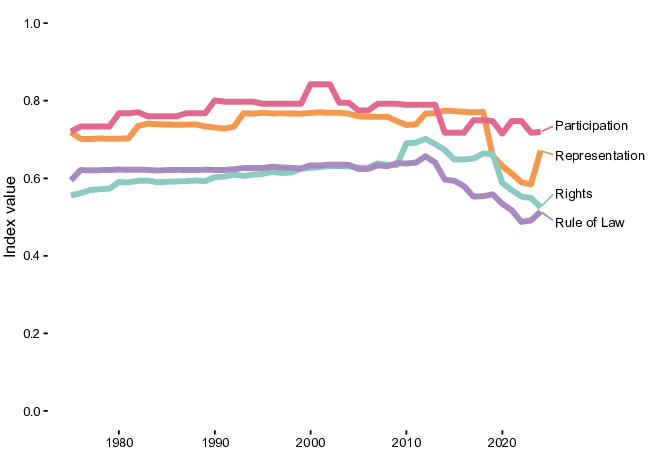

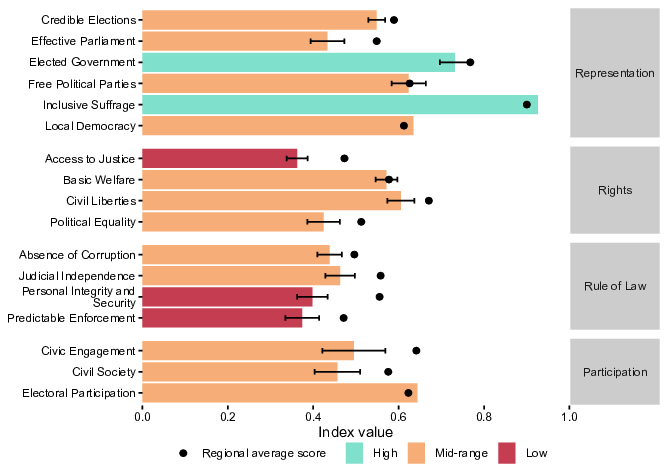

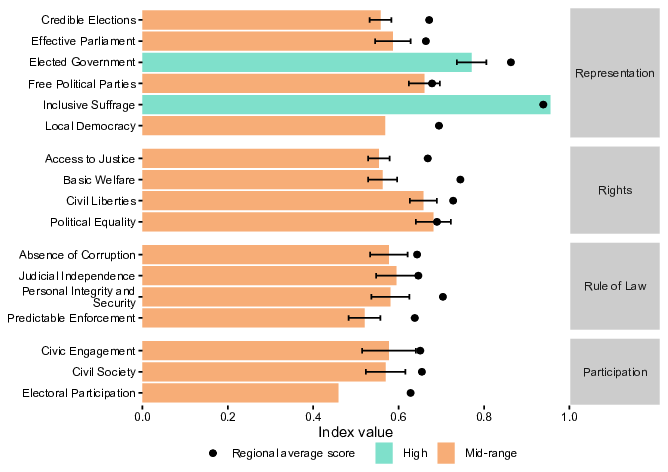

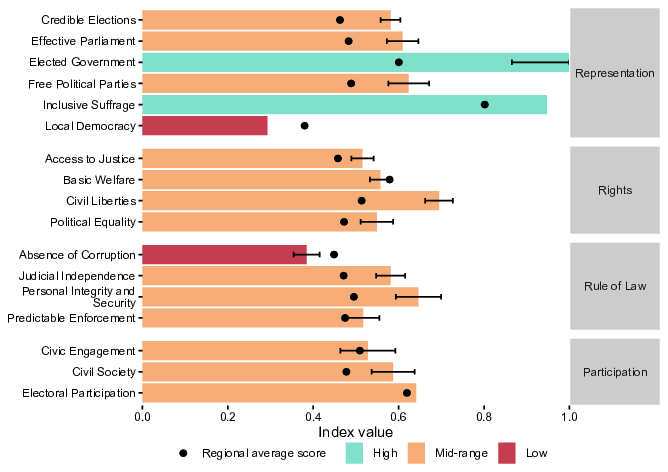

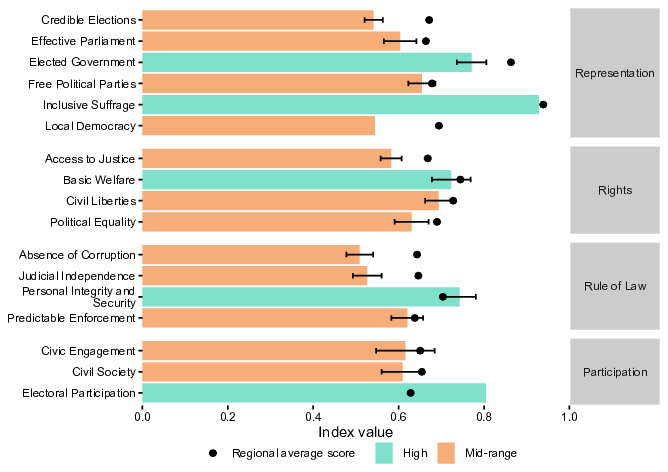

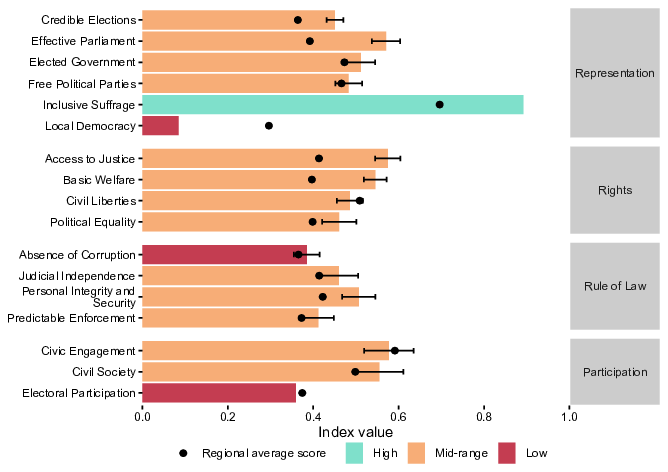

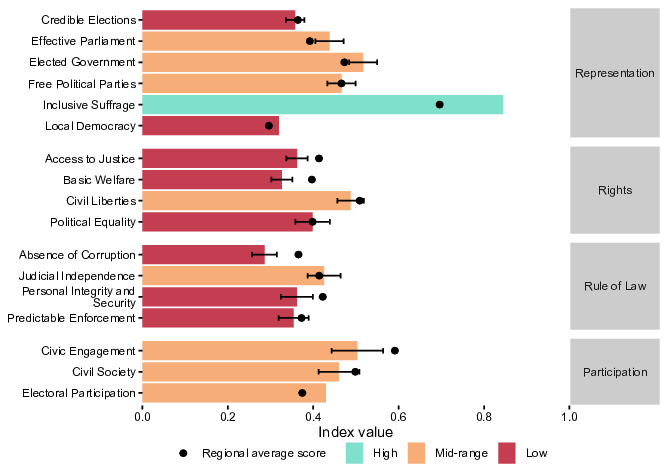

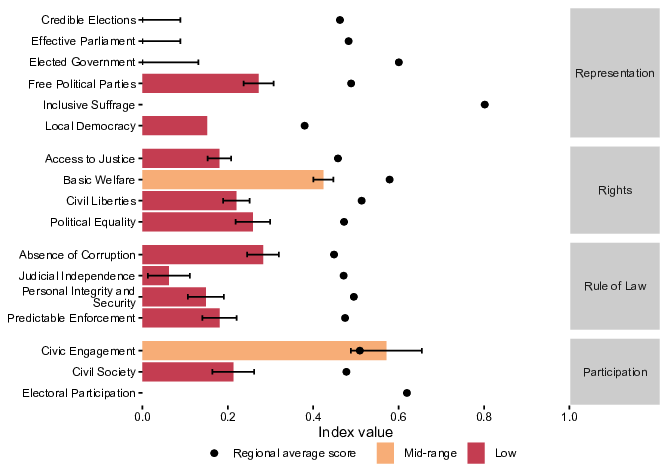

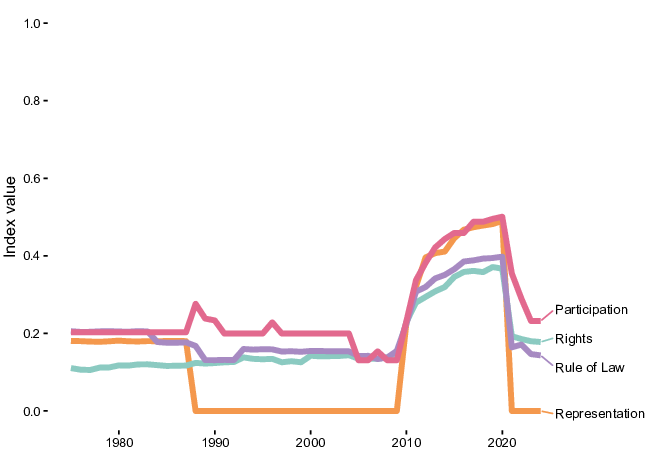

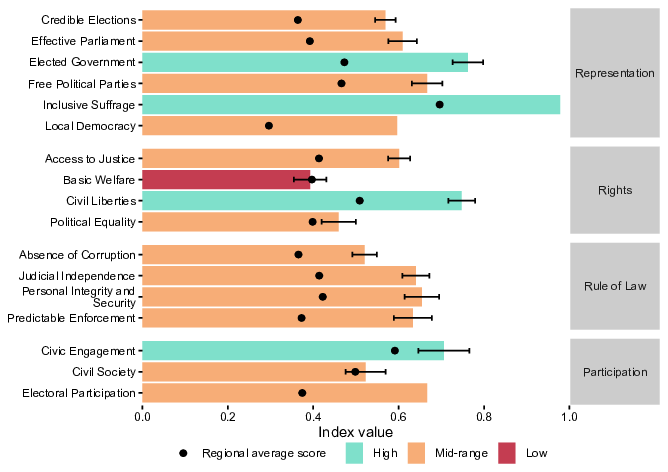

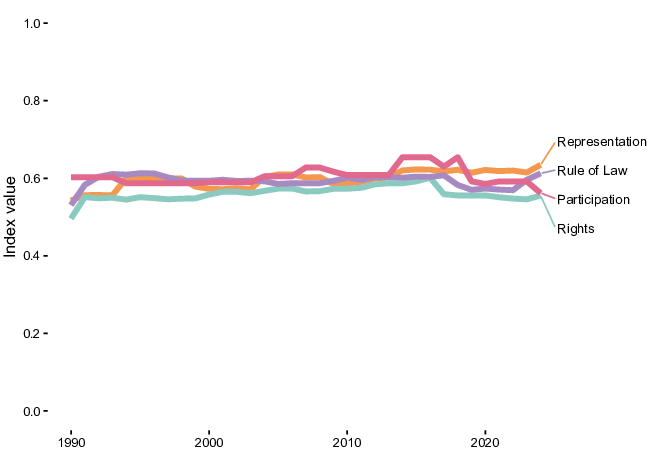

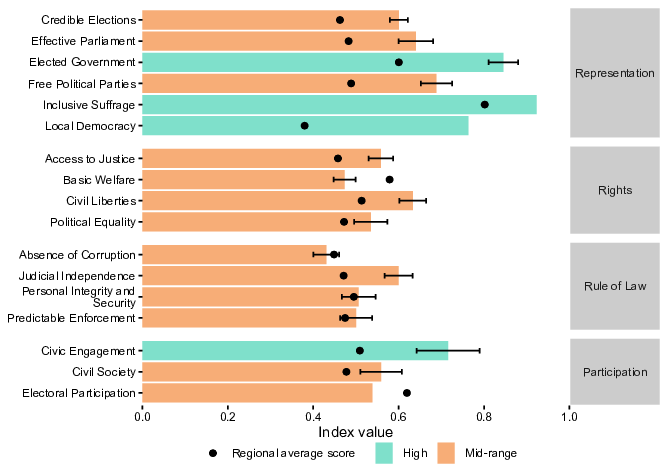

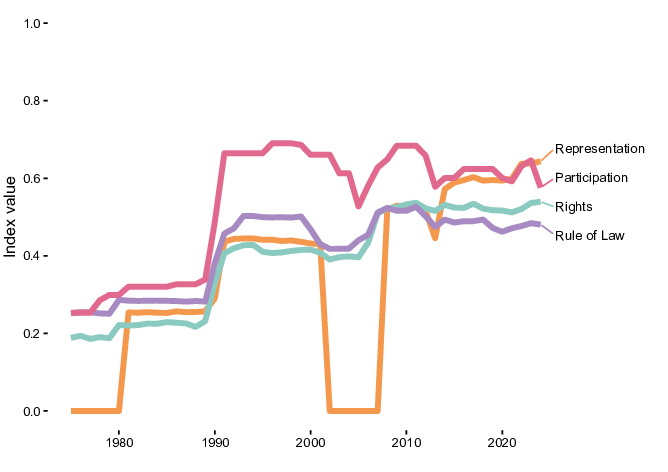

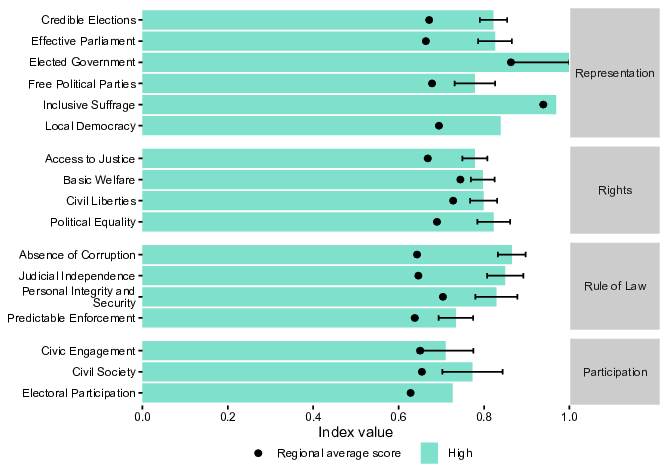

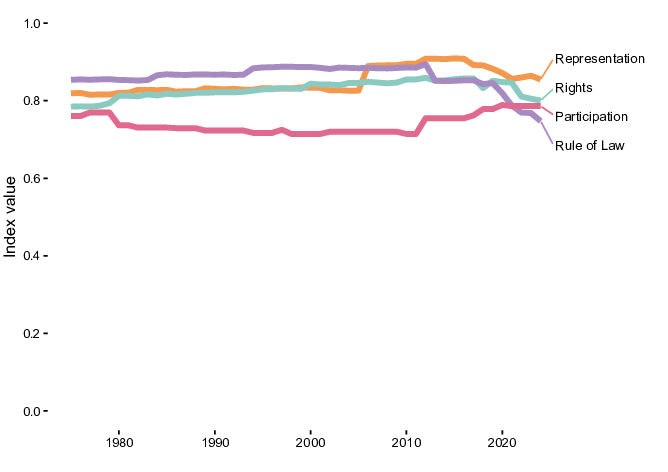

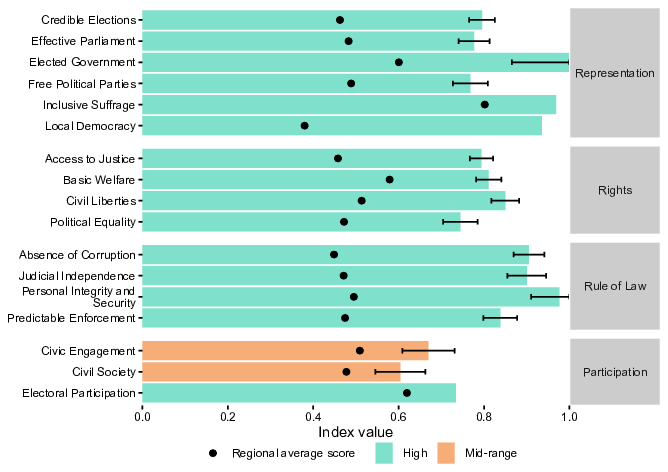

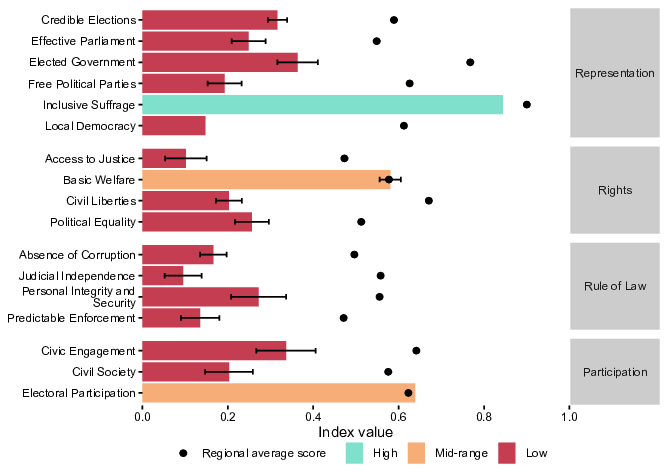

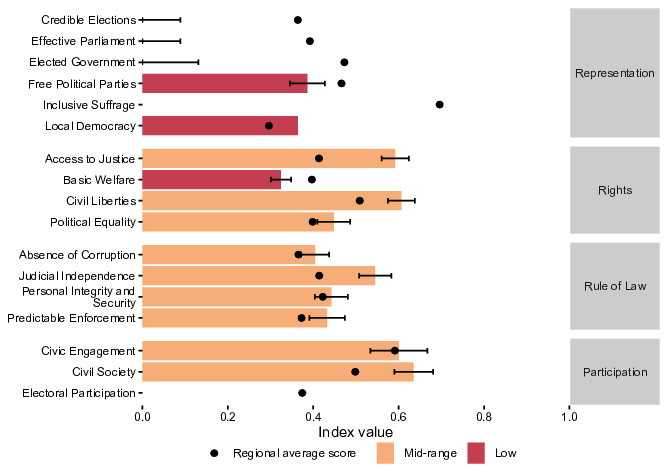

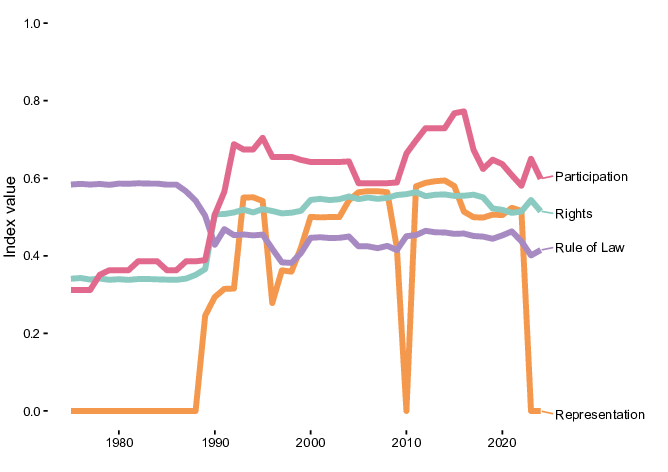

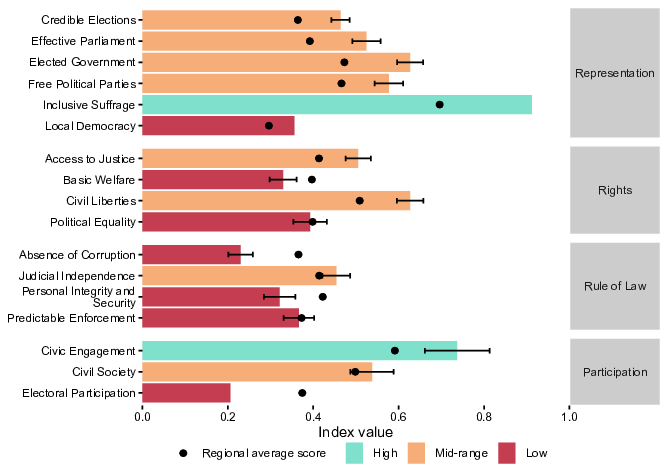

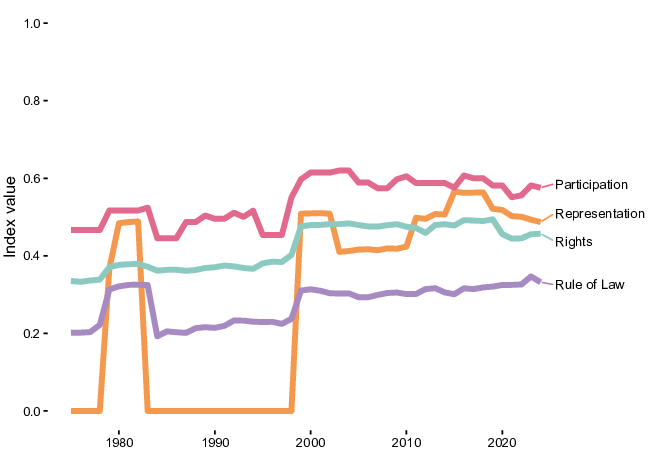

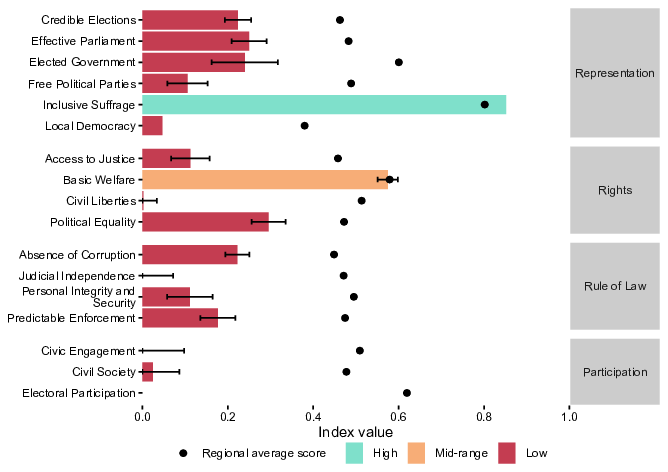

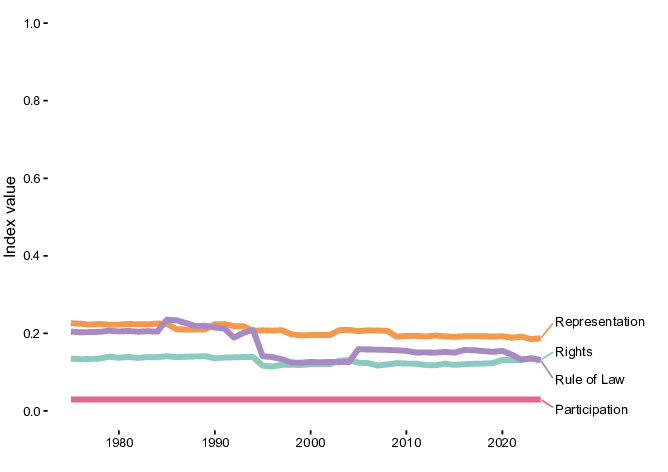

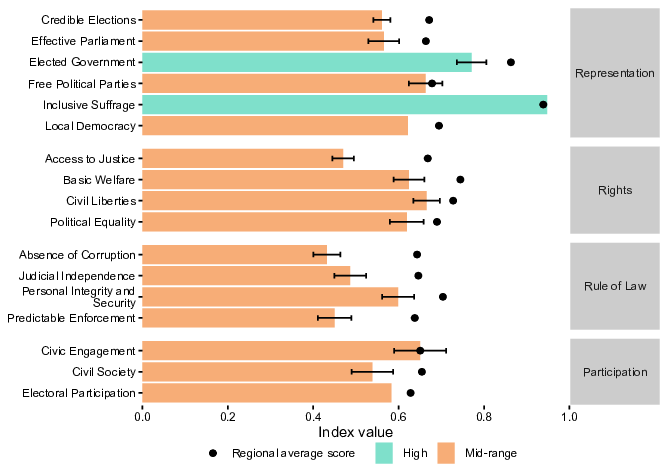

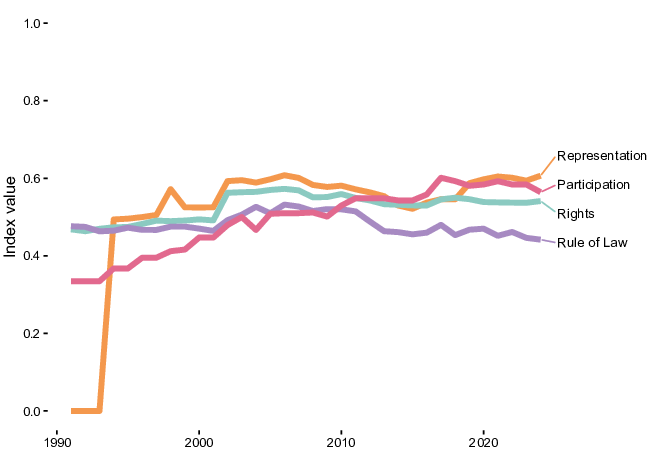

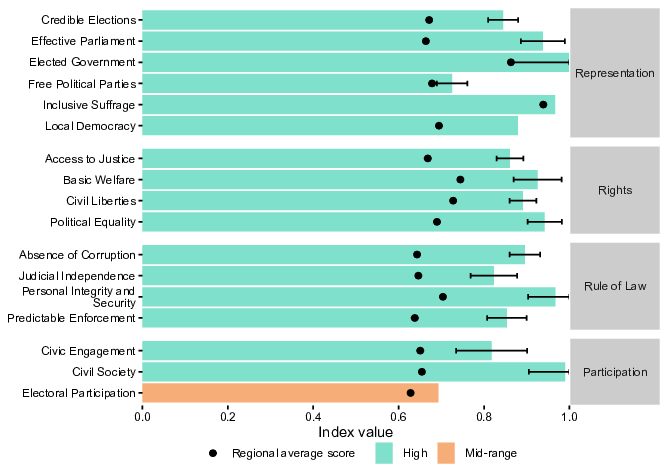

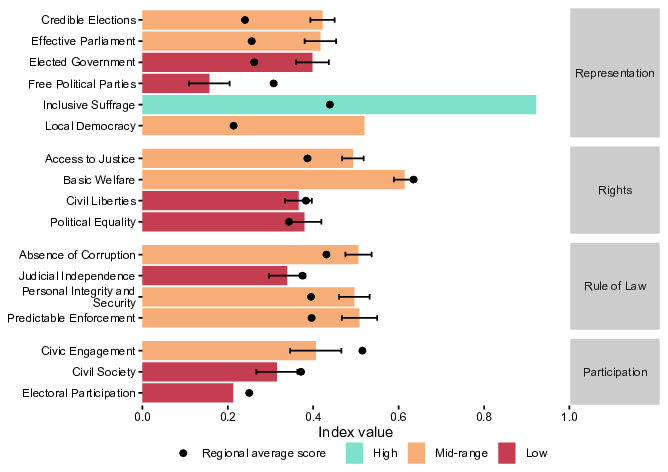

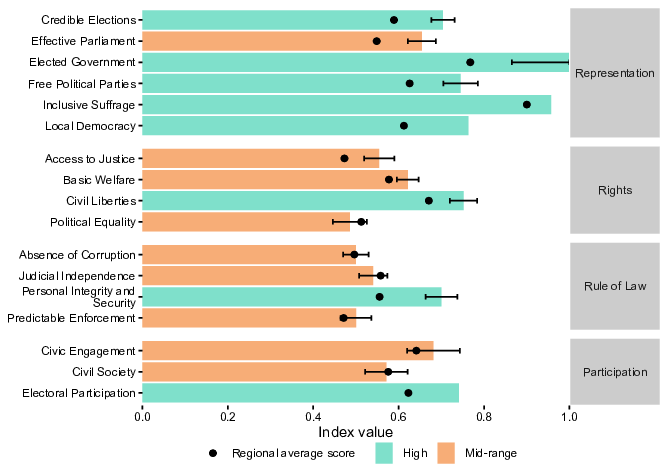

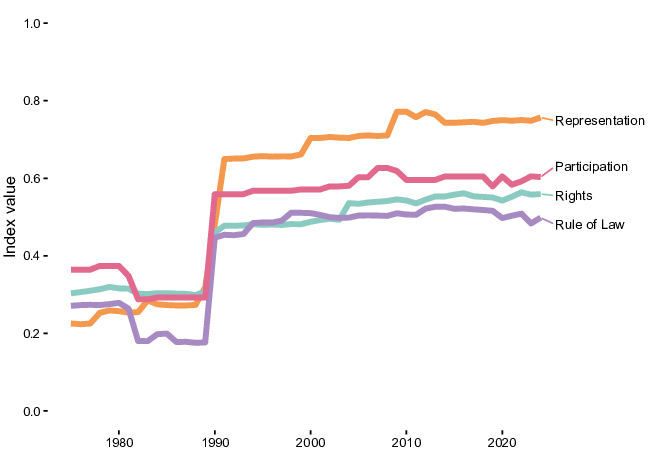

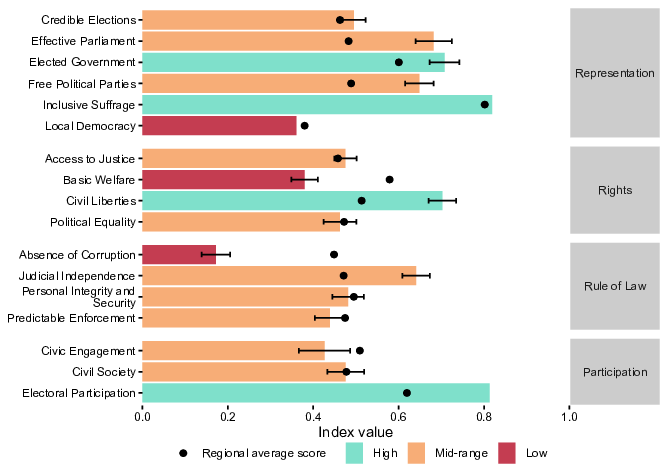

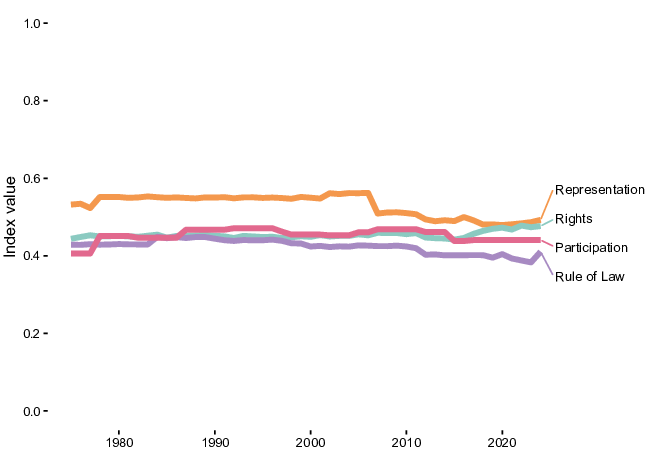

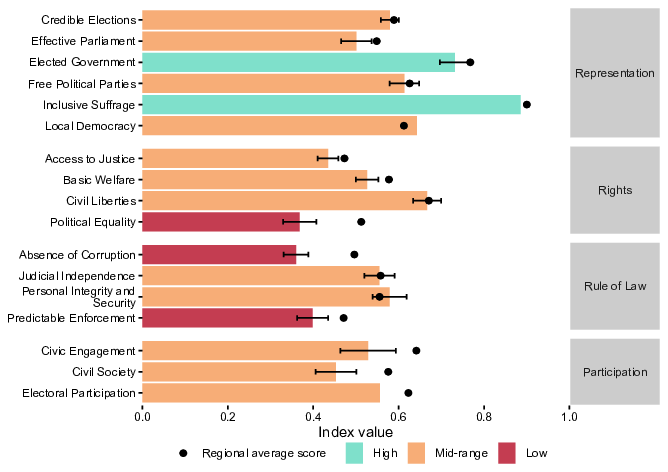

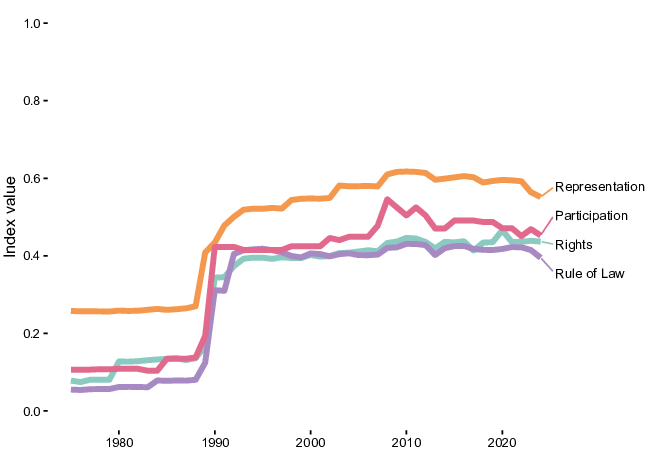

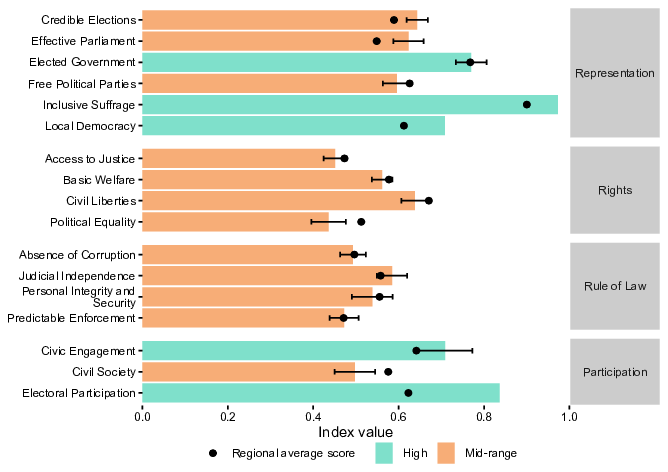

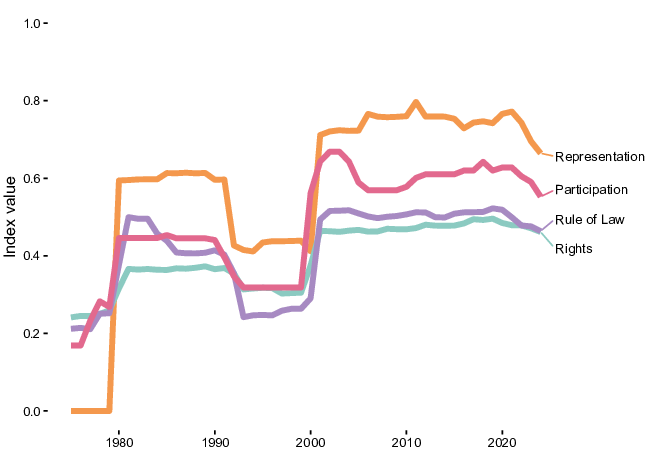

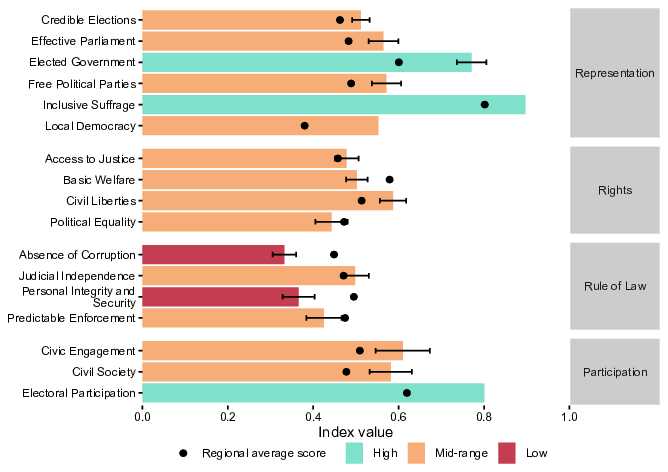

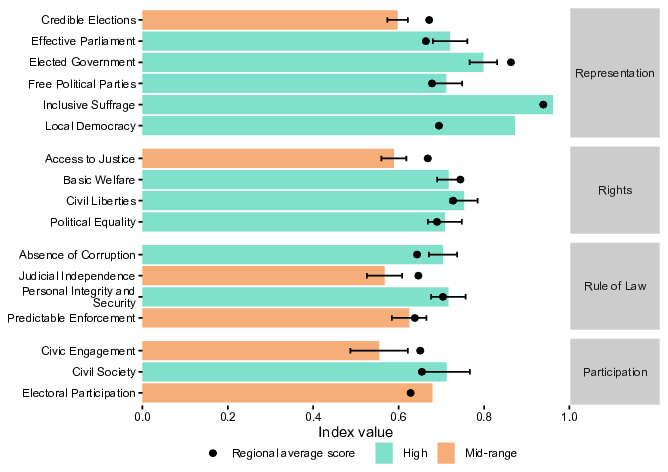

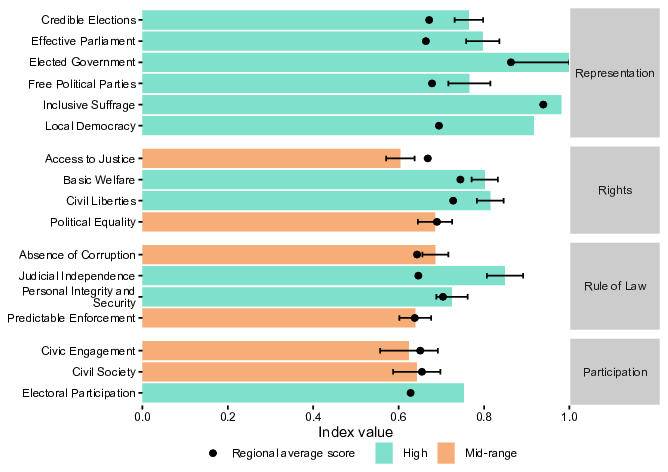

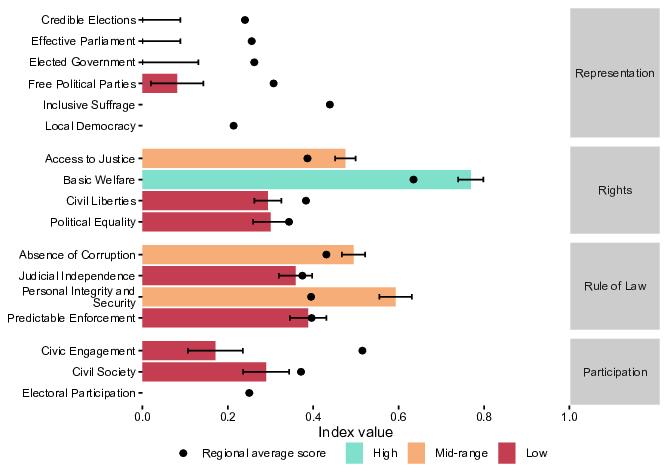

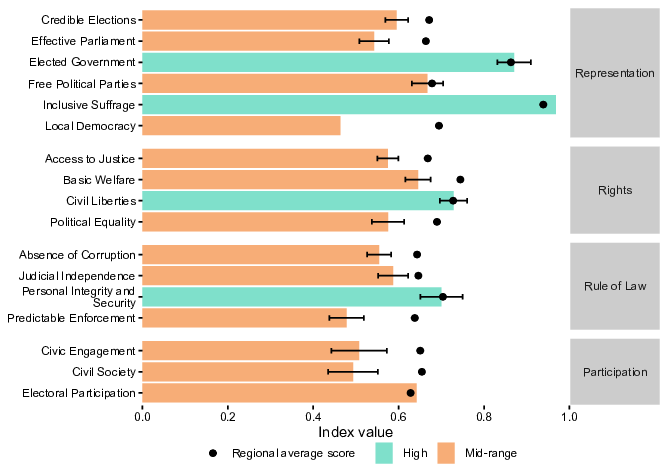

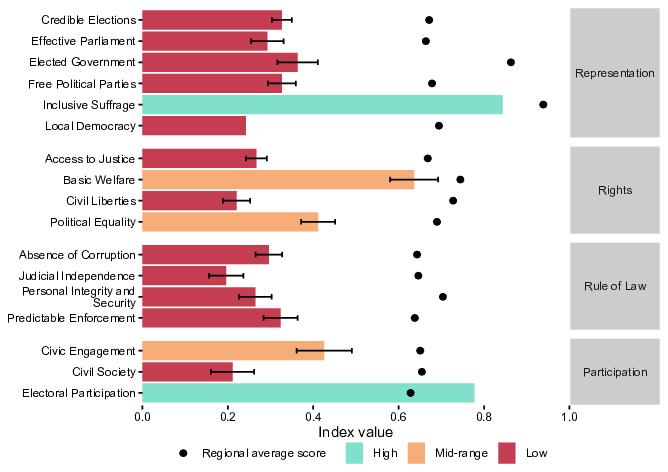

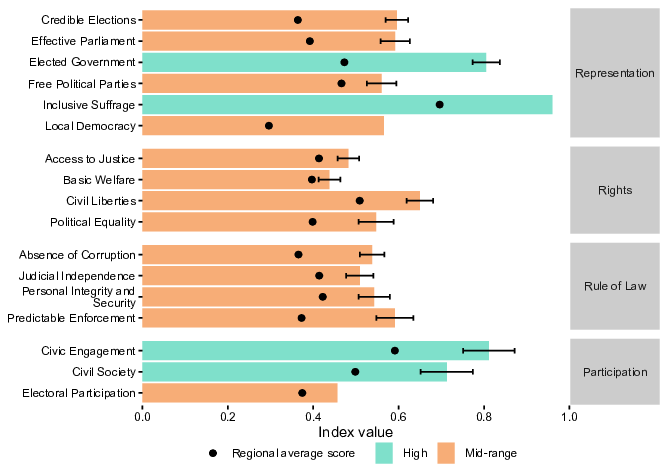

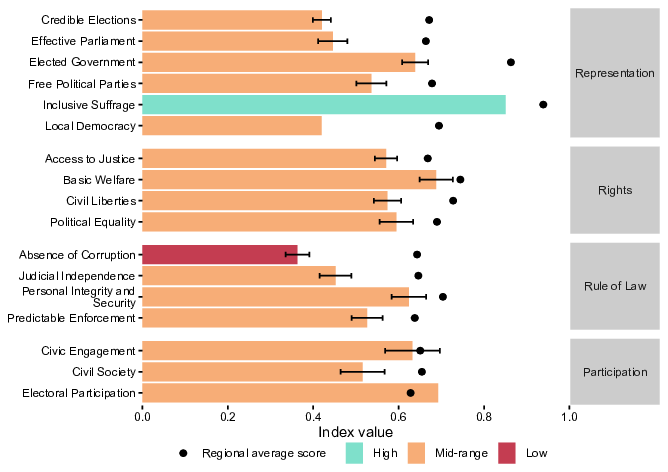

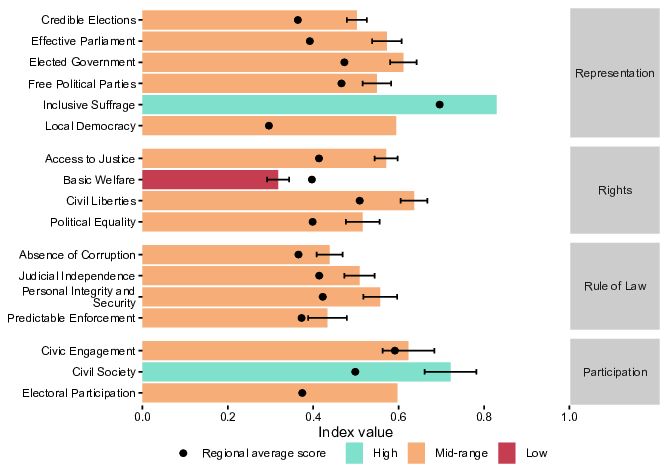

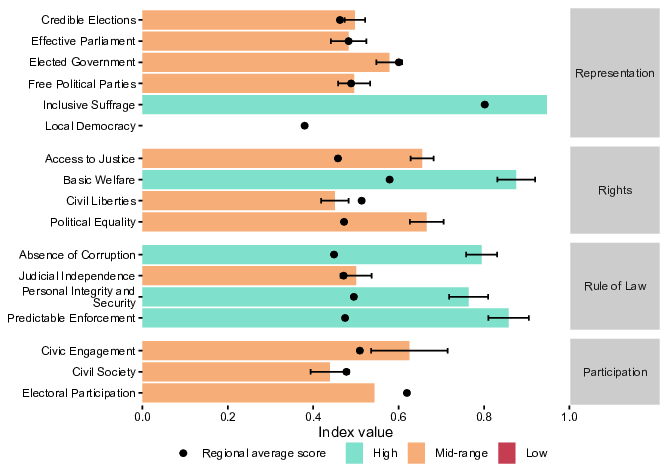

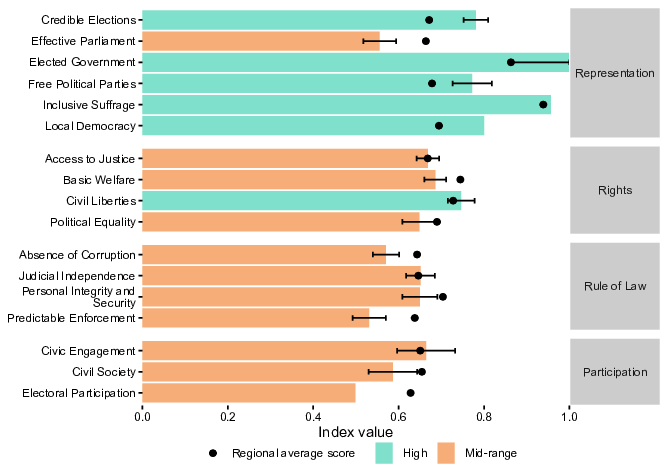

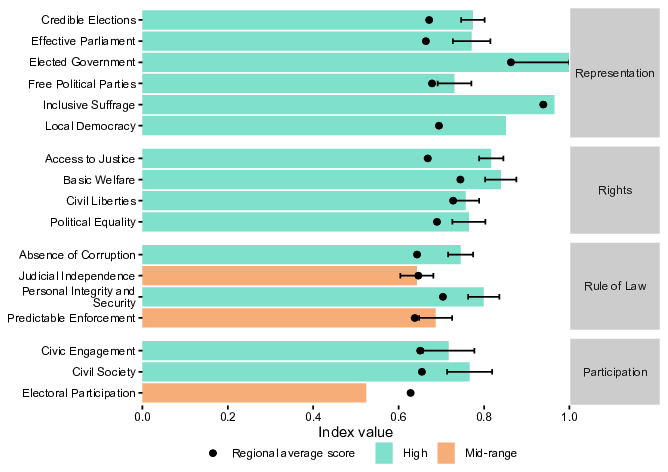

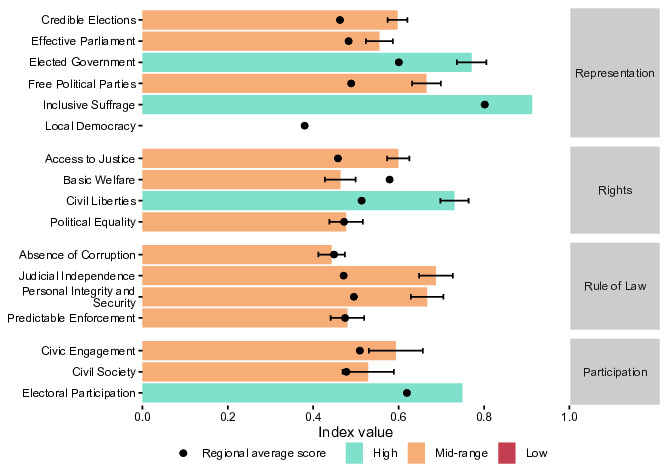

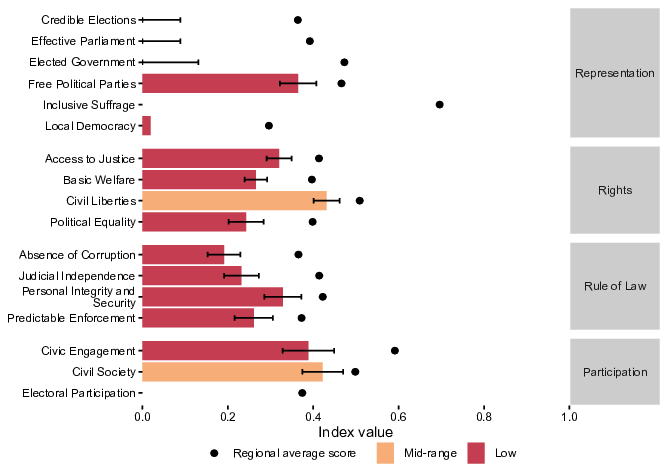

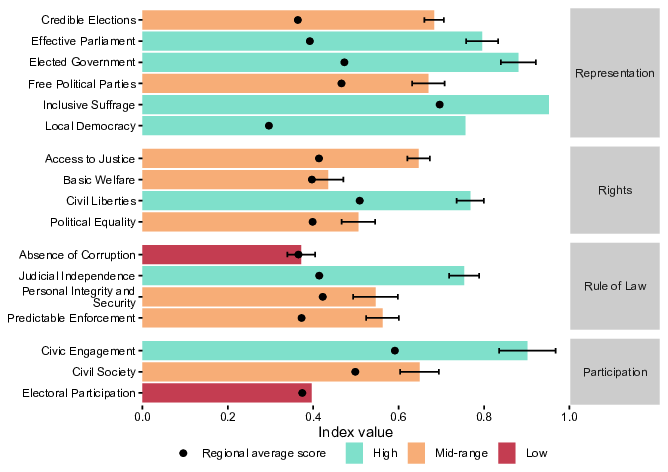

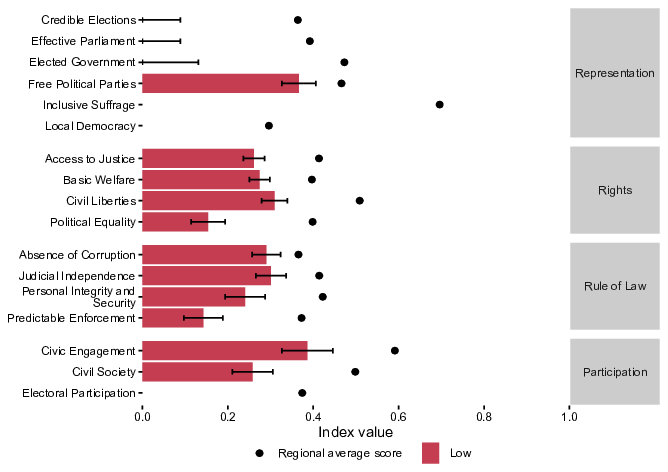

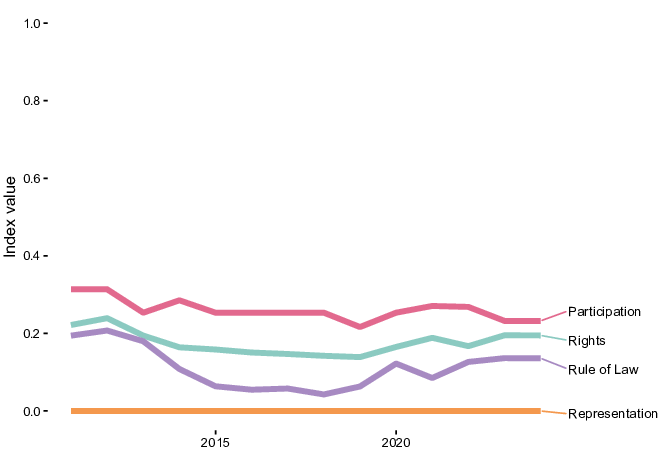

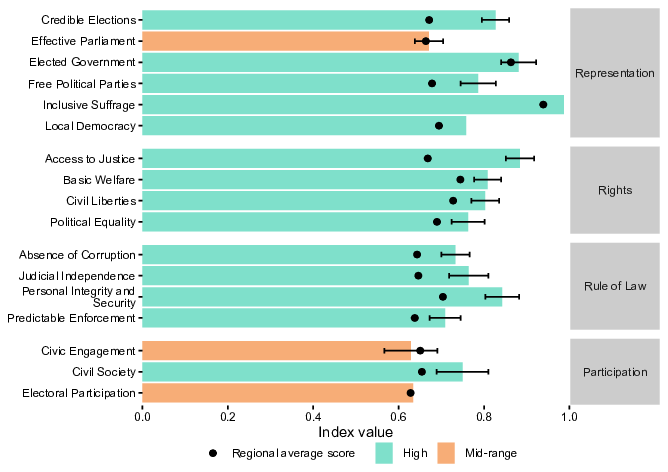

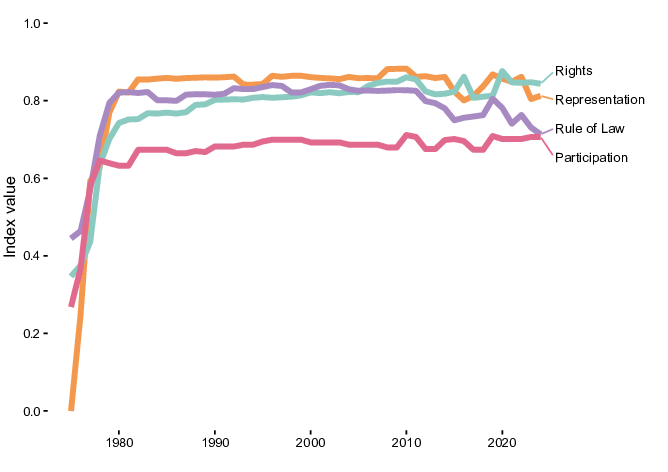

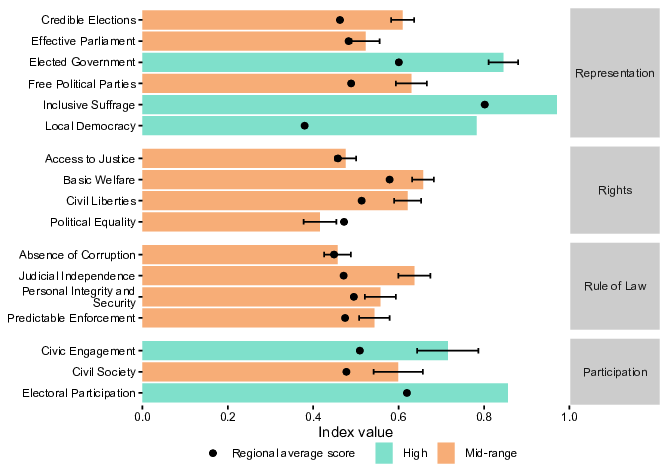

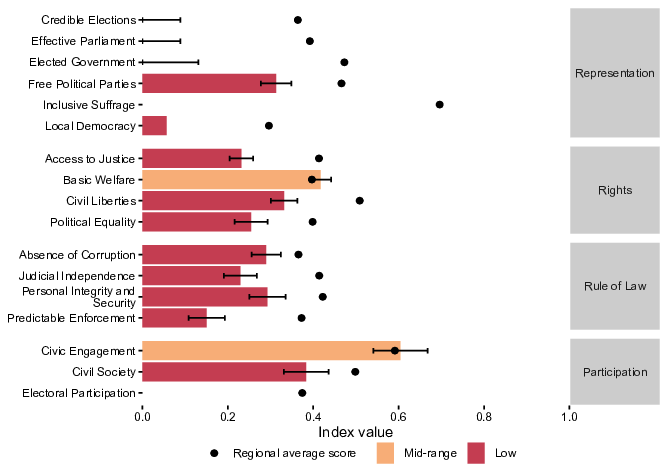

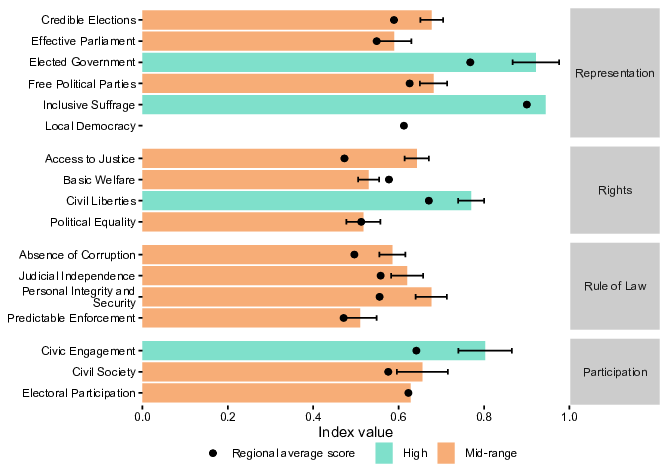

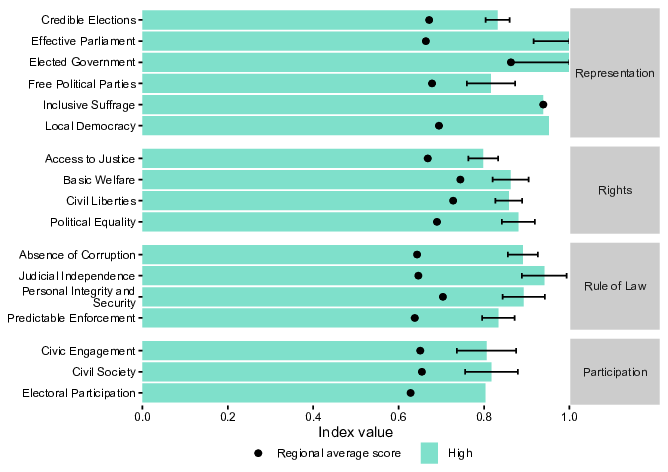

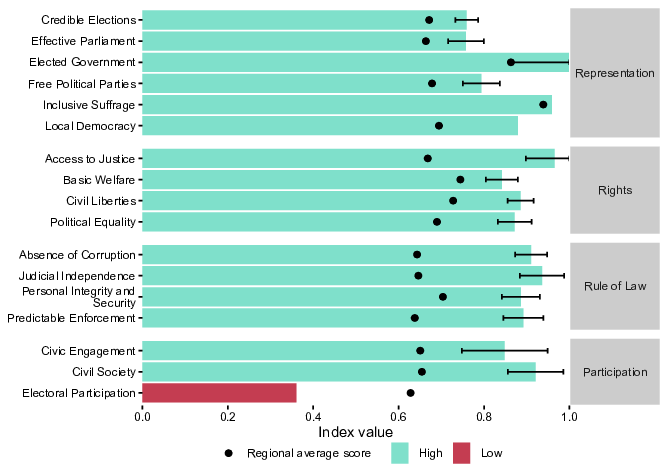

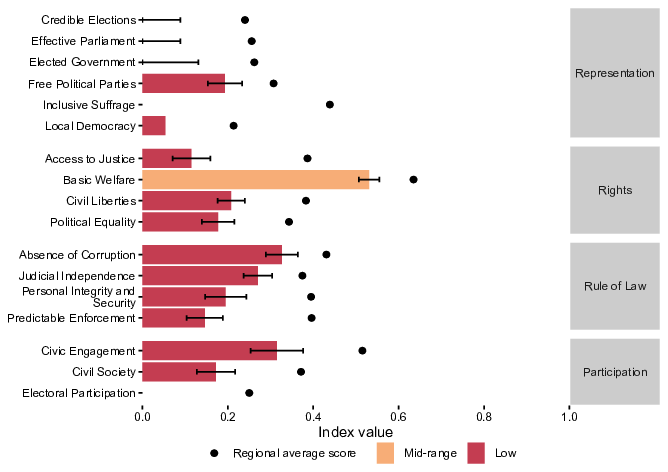

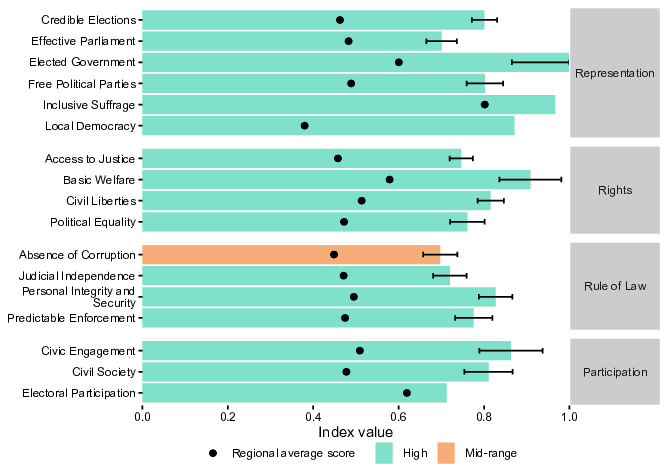

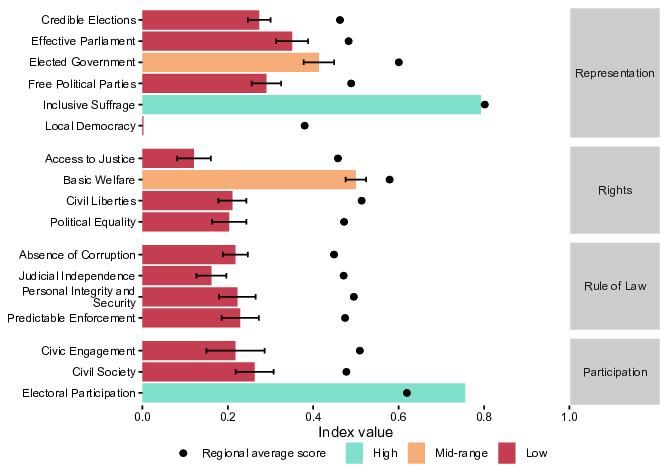

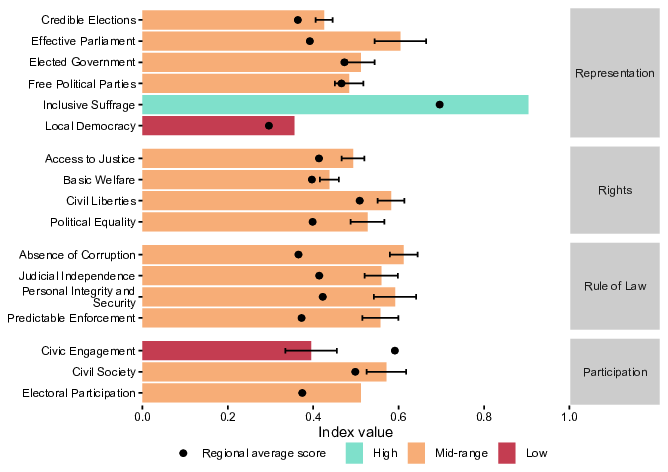

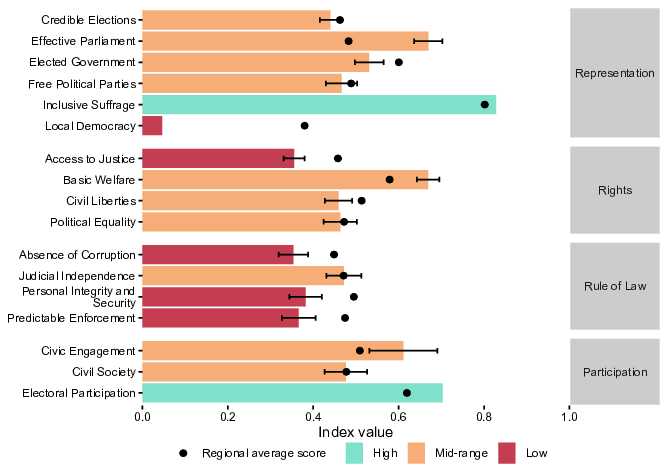

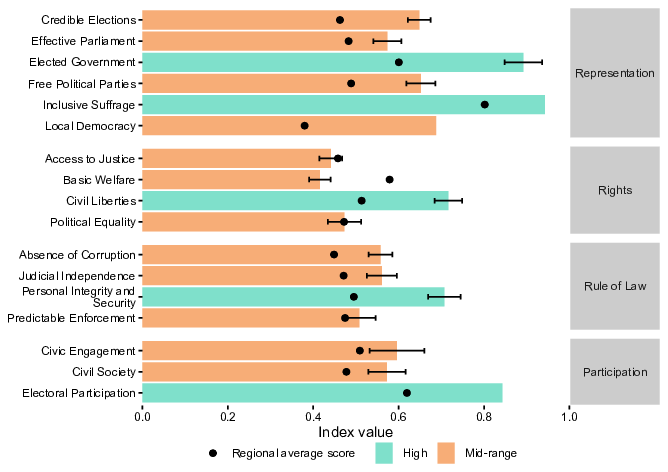

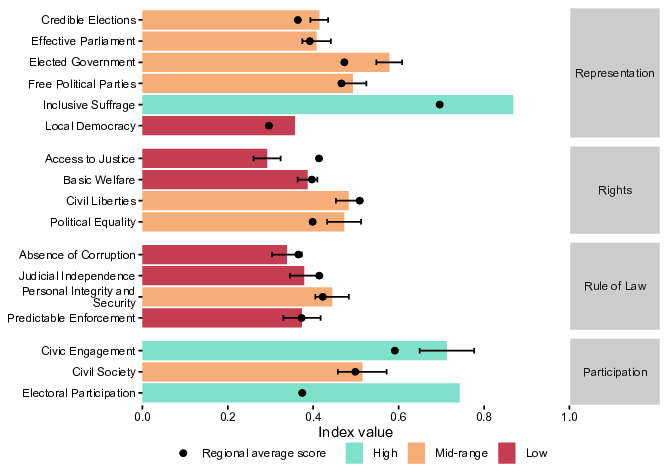

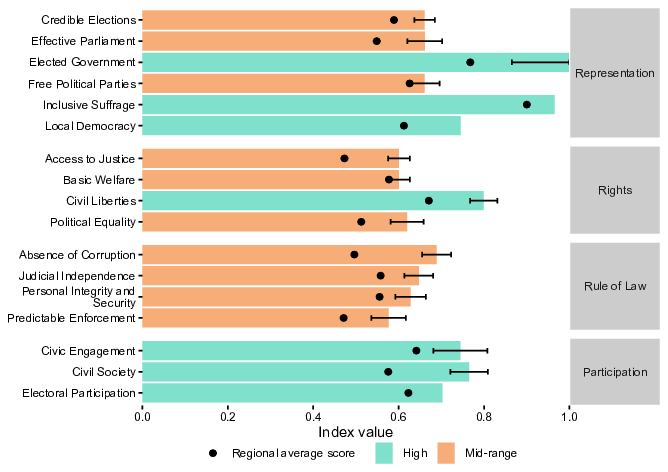

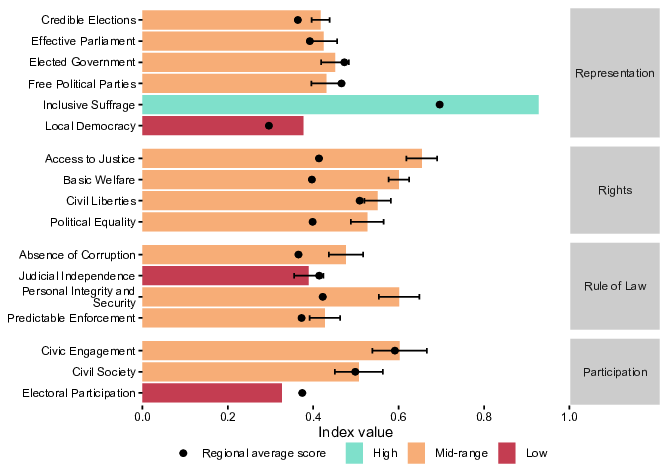

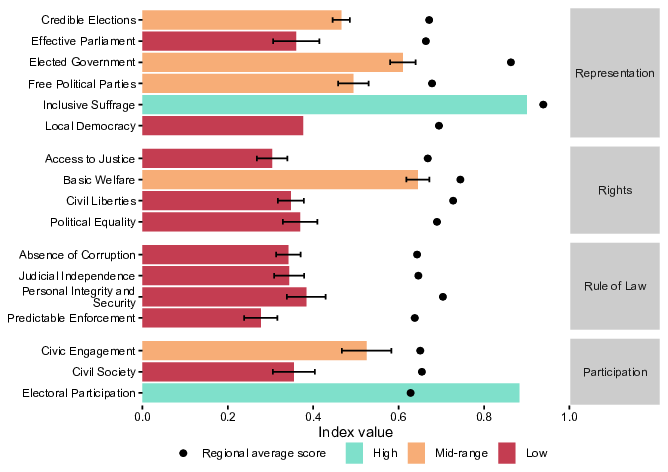

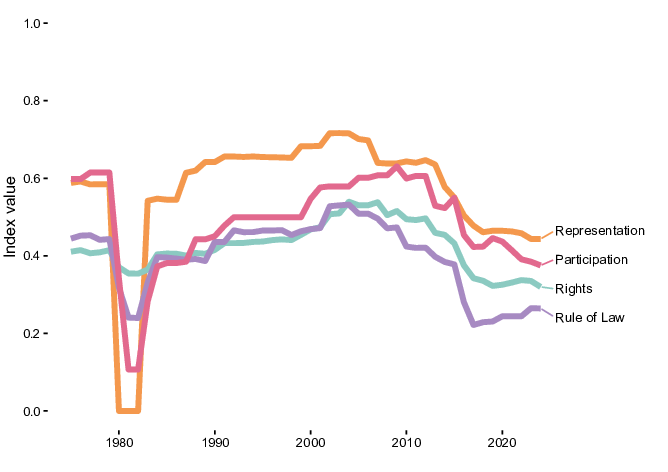

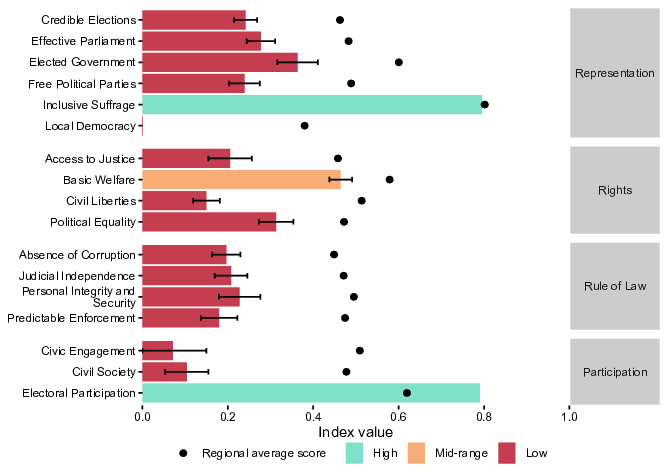

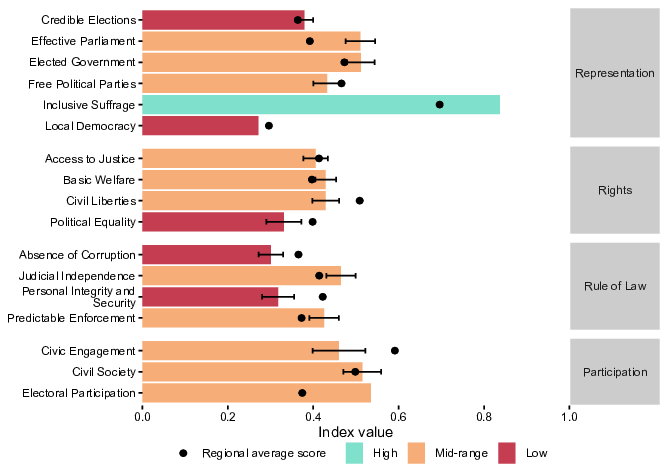

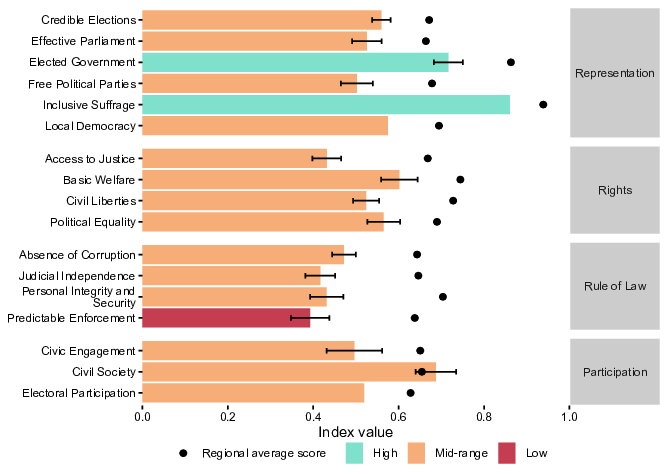

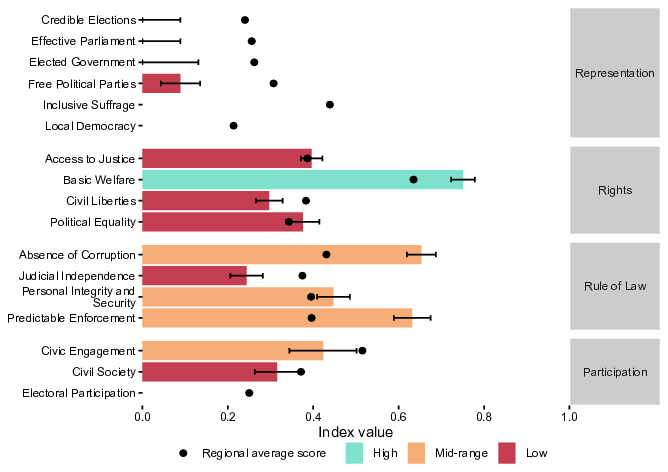

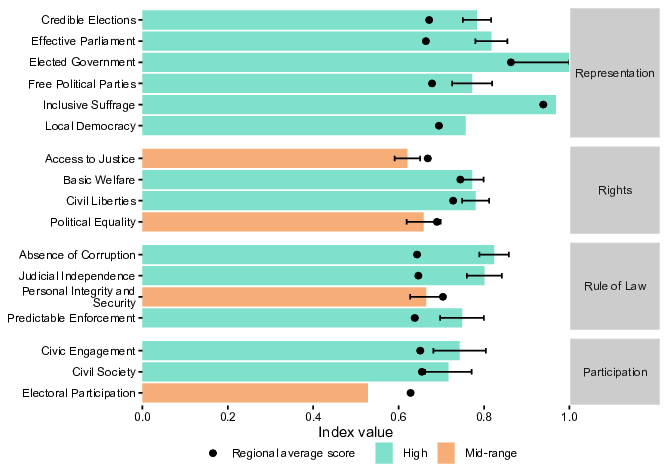

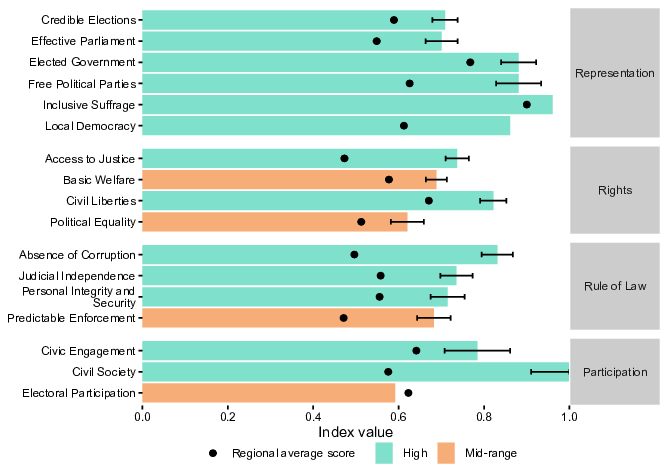

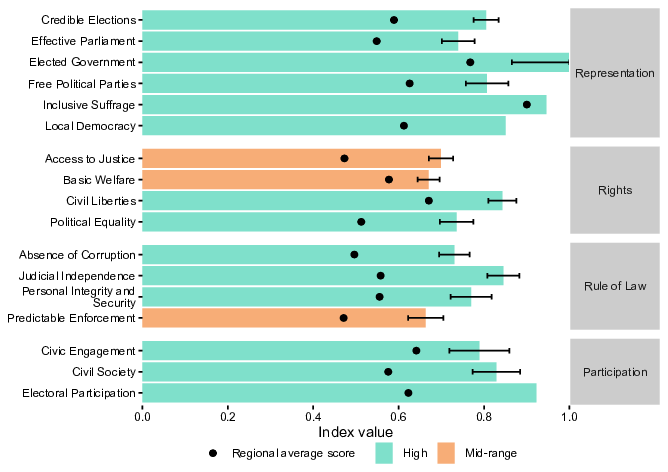

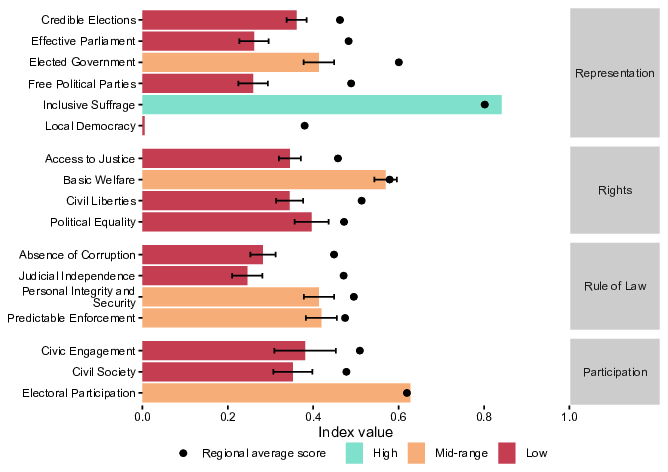

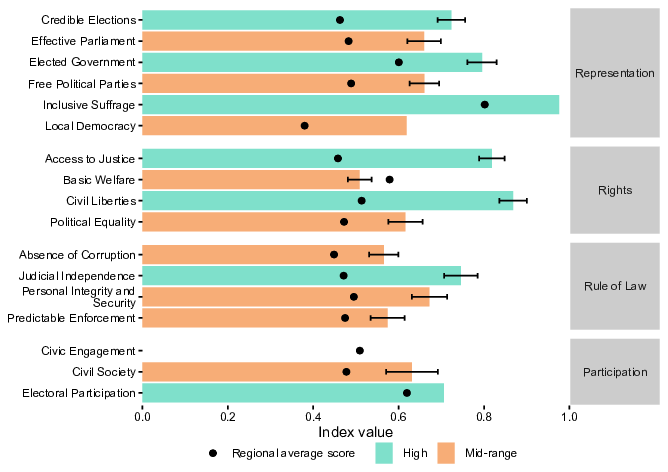

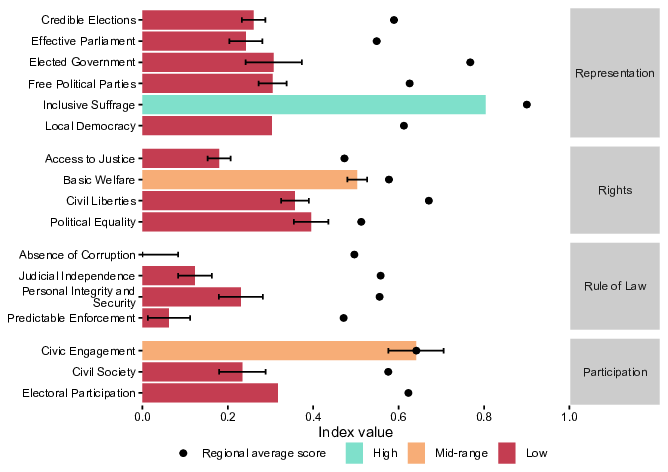

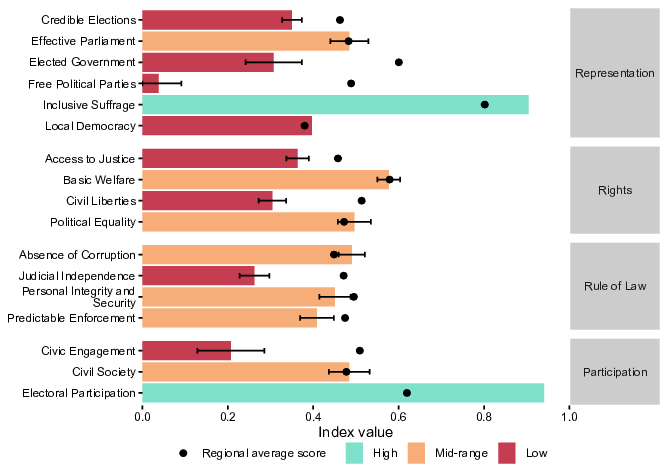

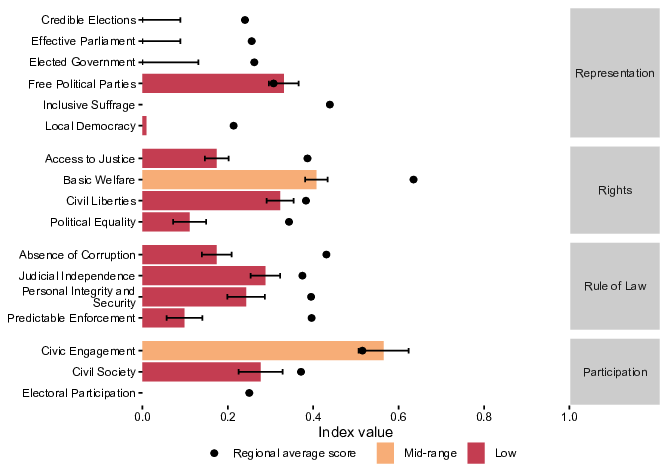

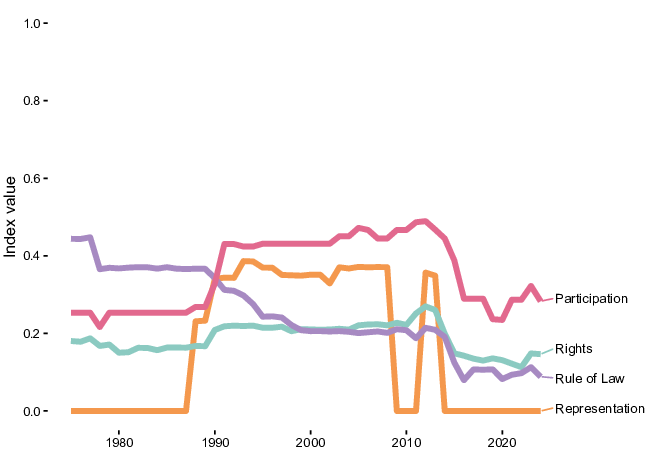

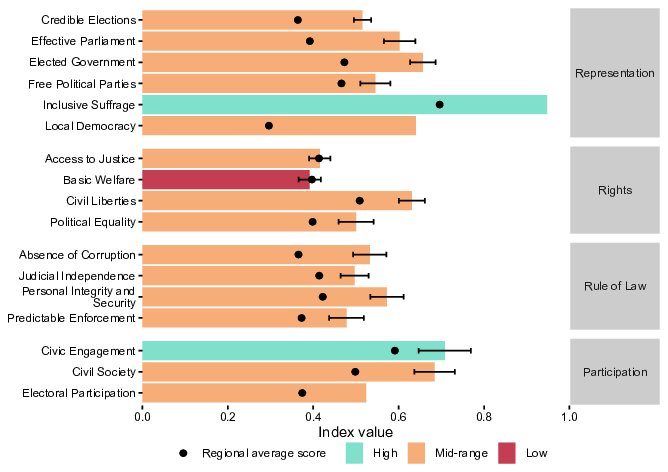

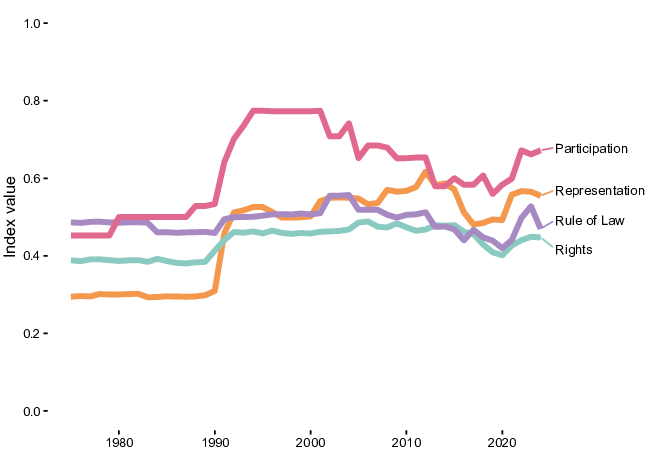

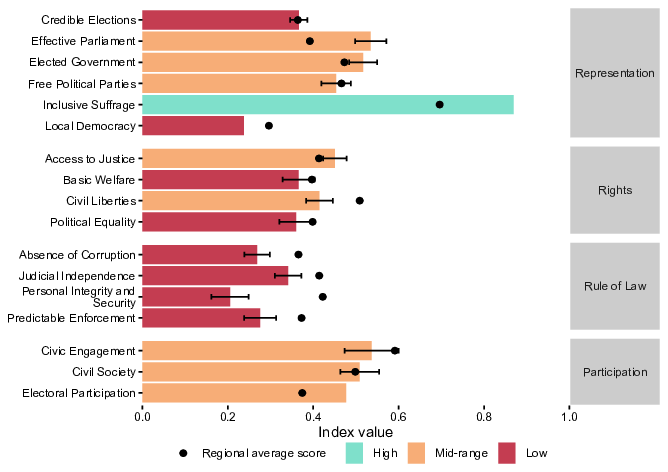

The GSoD Indices are organized around four core categories of democratic performance—Representation, Rights, Rule of Law and Participation. Each of the four categories includes several factors, such as Credible Elections or Judicial Independence. Among the four categories, performance was strongest overall in Representation, with 47 countries (27 per cent) achieving high scores in 2024. However, in the 2024 electoral super-cycle year, the global score for Representation fell to its lowest level since 2001, with seven times more countries declining than advancing. These declines occurred around the world in both low- and high-performing democracies. Rule of Law continues to be the category with the weakest performance. In 2024, 71 countries (41 per cent) were categorized as low-performing. The highest number of aggregate-level declines also occurred in the Rule of Law category; 32 countries (19 per cent of those assessed, and most low- or mid-range-performing) registered downturns in this category in 2024. European countries accounted for 38 per cent of these downturns, followed by countries in Africa, the Americas, Asia and the Pacific, and West Asia. Declines within the Rule of Law category were most concentrated in the factor of Judicial Independence.

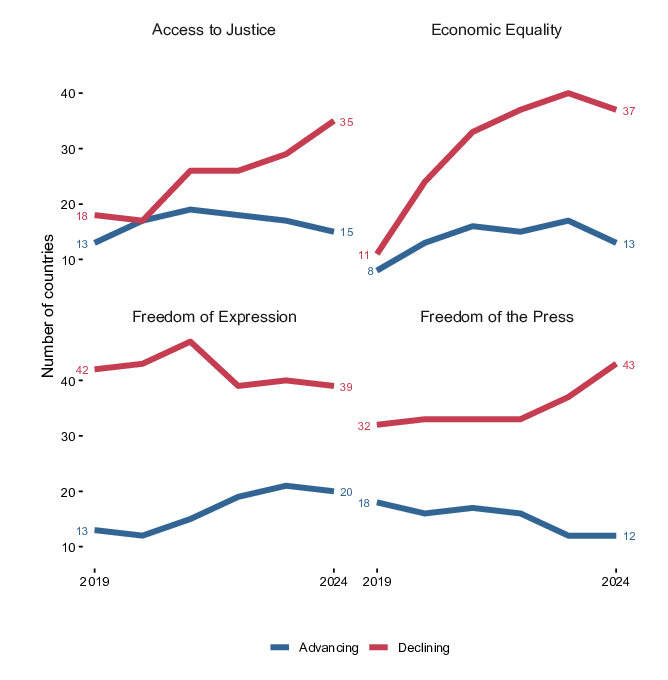

Within the Rights category, the most extensive global decline occurred in Freedom of the Press, followed by Freedom of Expression, Economic Equality and Access to Justice. Performance in Freedom of the Press declined in 43 countries, nearly one quarter (24.9 per cent) of those covered. This marks the broadest decline in this factor since the beginning of our data set (1975), signalling a serious threat to public accountability and informed political participation.

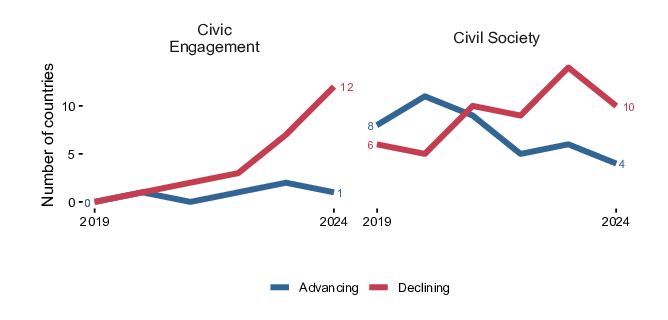

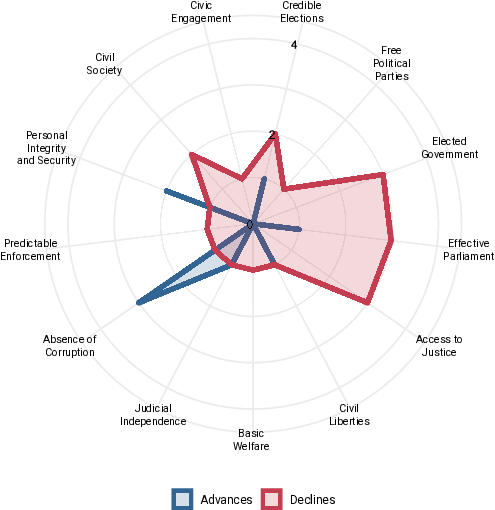

Participation remained relatively stable, with only 11 countries experiencing notable changes when comparing 2024 to 2019. Declines (9 countries) outweighed advances (2 countries), with most of the declines occurring in countries that were already low-performing, including Afghanistan, the Central African Republic, Kuwait, Myanmar, Nicaragua and Russia. The two countries that improved were Brazil and Fiji, both high performers in this category.

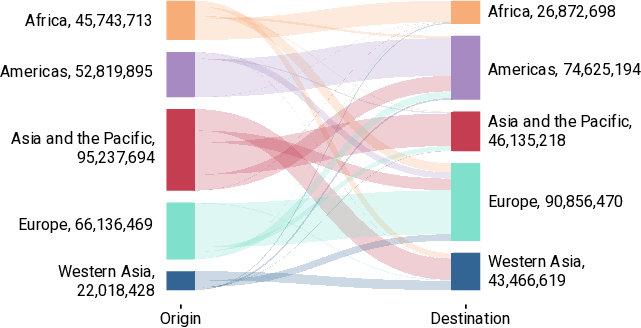

The second part of this document discusses the intersection of global migration flows and their relationship to democracy and democratic institutions. Migration now affects a growing share of the world’s population, with 304 million people (or 3.7 per cent of the global population) living outside their country of birth in 2025. Contrary to some popular narratives, most of the people who leave their country of birth move to a neighbouring country or stay within their region.Global migration has emerged as a key factor contributing to the current climate of uncertainty, raising complex questions about citizenship, belonging, the universality and equality of rights, and what it means to be an inclusive democracy today.

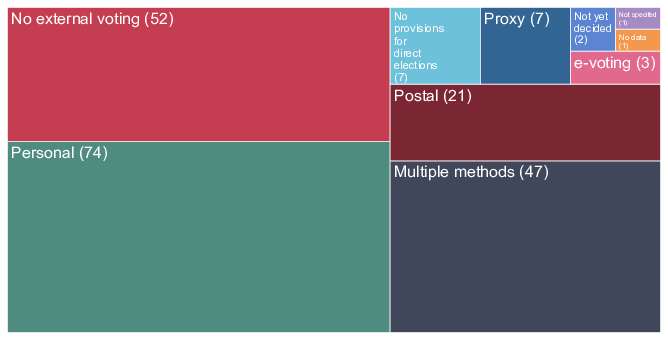

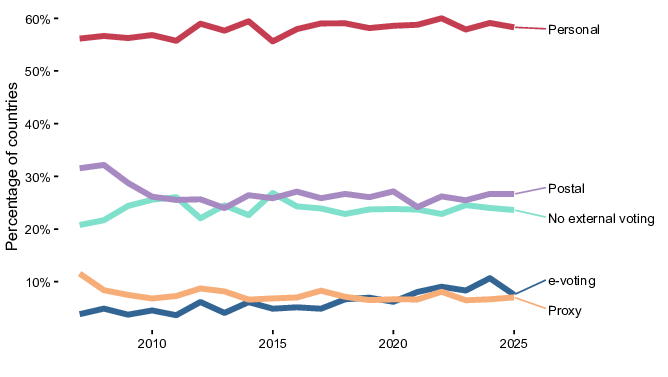

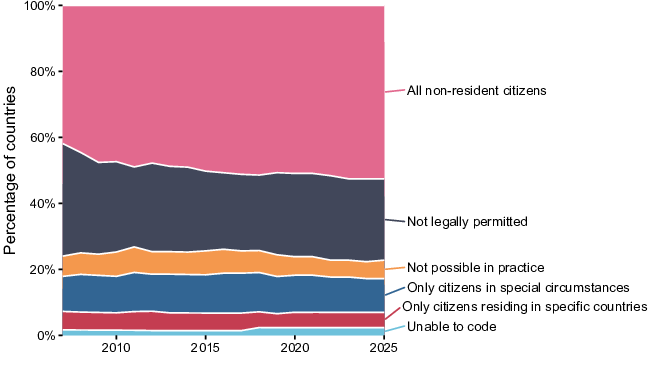

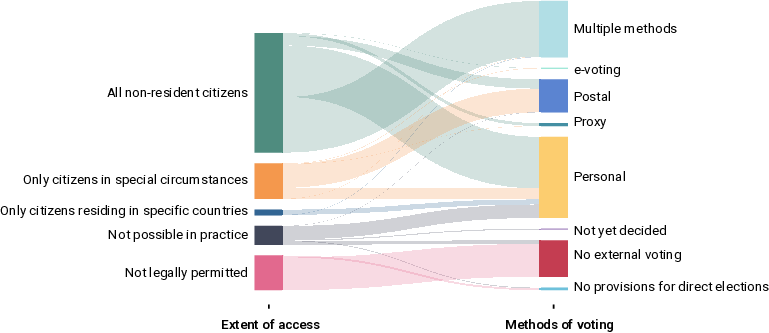

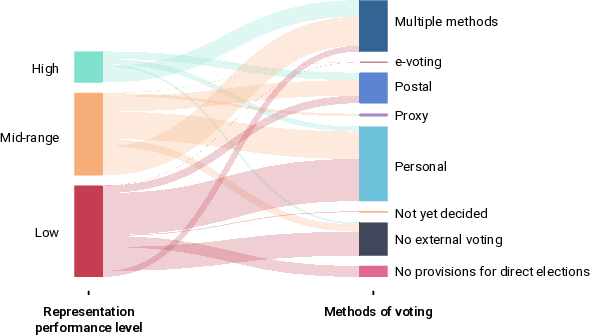

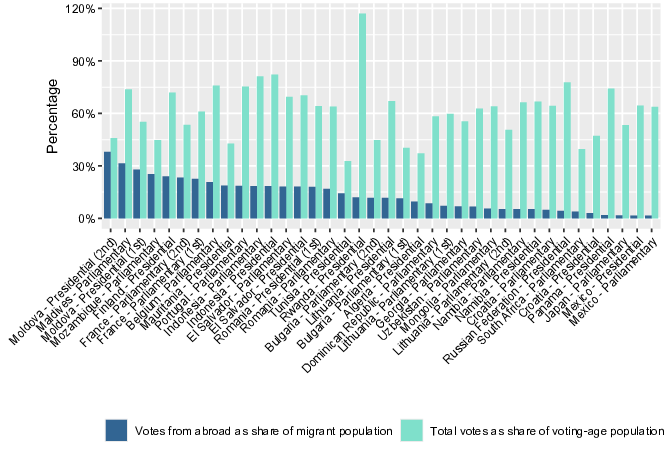

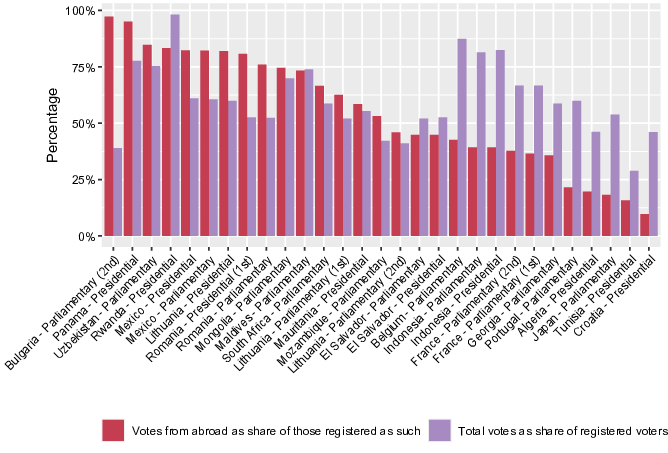

Building on trends identified in the GSoD Indices and in the Democracy Tracker, this report focuses on the technical, legal and institutional dimensions of voting rights for citizens residing abroad. We find that expanding political participation contributes to democratic resilience, and that out-of-country voting (OCV) contributes to the sense of belonging that fosters this resilience. Benefits can accrue to both home and host countries, including by spreading democratic norms across borders. However, data collected for this report show that diaspora turnout rates are relatively low, and the information that is publicly available about eligible diaspora voters is limited and uneven. While there is no one-size-fits-all OCV model, we know that the legal and administrative design of OCV systems strongly affects participation rates, and broad-based enfranchisement requires carefully designed policies—for both registration and encouraging turnout. To persevere, democracy requires patience, maintenance and, at times, reinvention. The work of democracy is never finished: as the scale and patterns of migration evolve, democracies will have to maintain and regularly re-evaluate institutional frameworks, including, as noted here, the meaning, boundaries and mechanisms of involving non-resident citizens in political decision making.

Data sources

The Global State of Democracy (GSoD) report, the flagship publication of the International Institute for Democracy and Electoral Assistance (International IDEA), provides annual analysis of democratization across the globe.

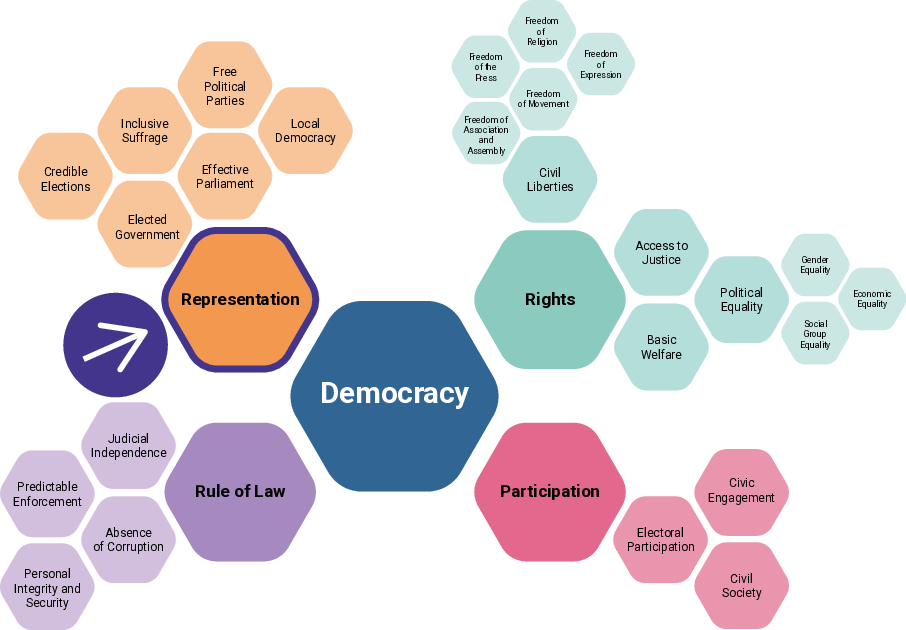

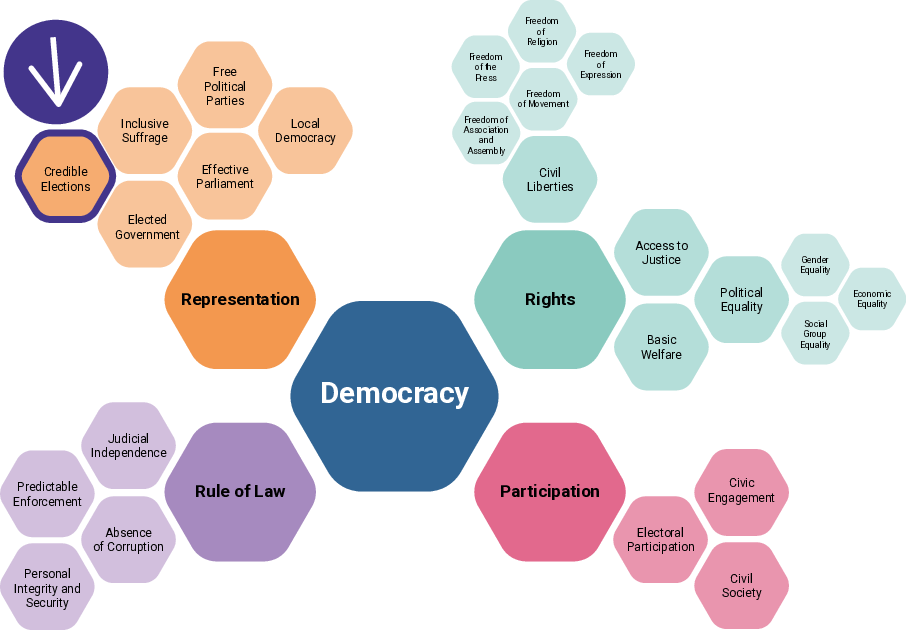

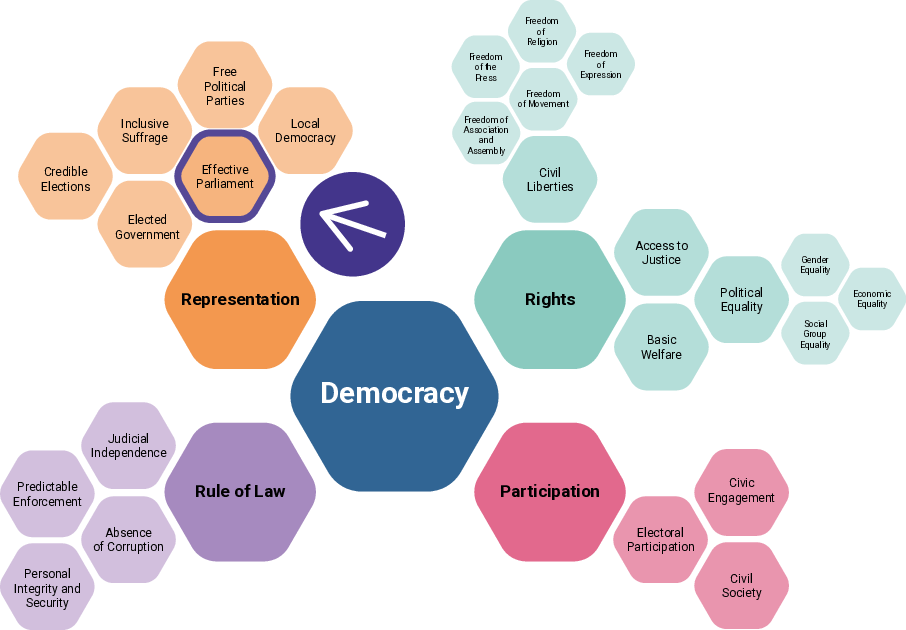

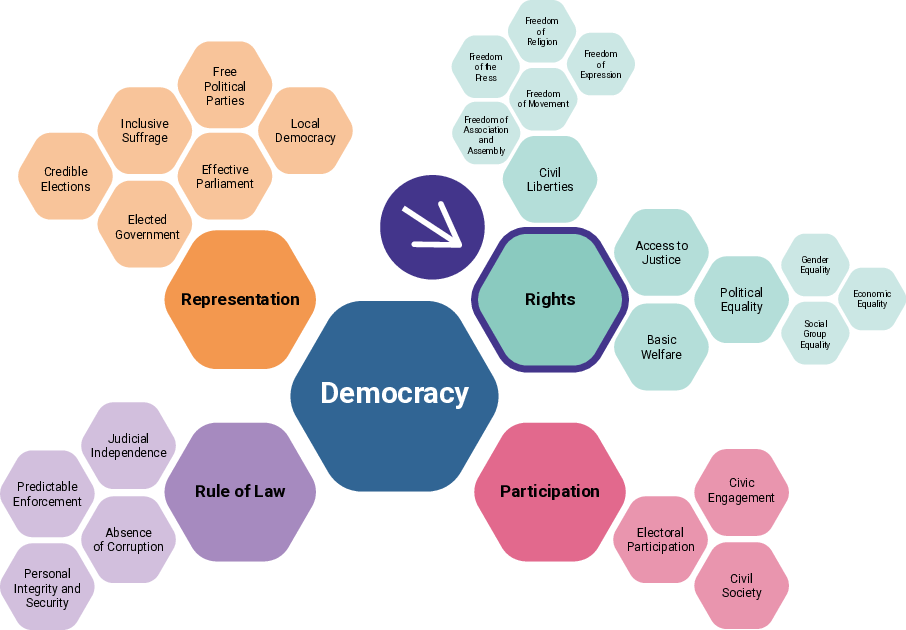

Version 9 of the GSoD Indices, a quantitative data set, provides the majority of the data on which this report is based (unless otherwise stated). The Indices measure national performance across discrete areas of democracy, broadly understood as a system in which there is public control over decision making and decision makers, and in which there is equality in the exercise of that control. While this report refers to the five-year period from 2019 through December 2024, the complete data set covers the years 1975–2024 (International IDEA n.d.e).

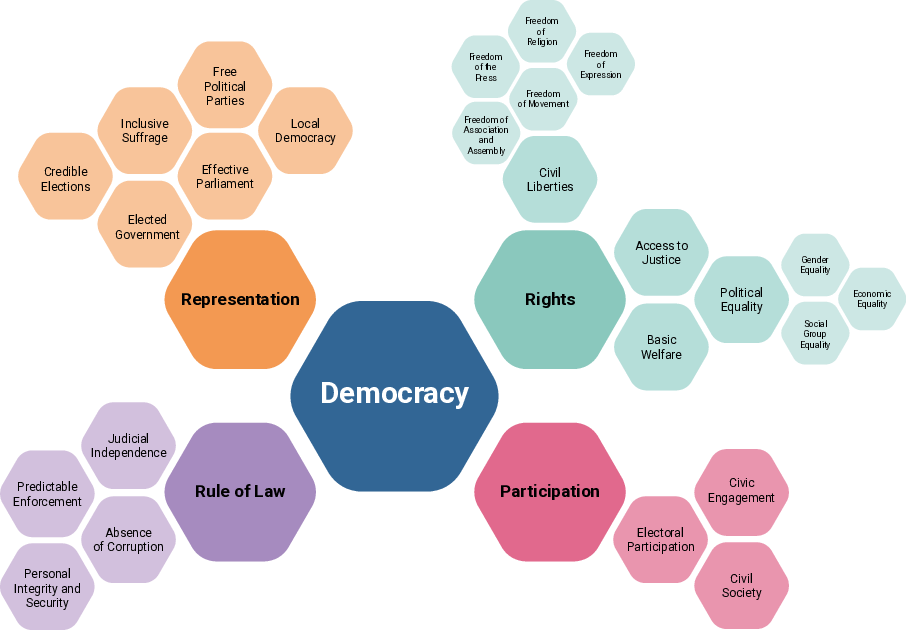

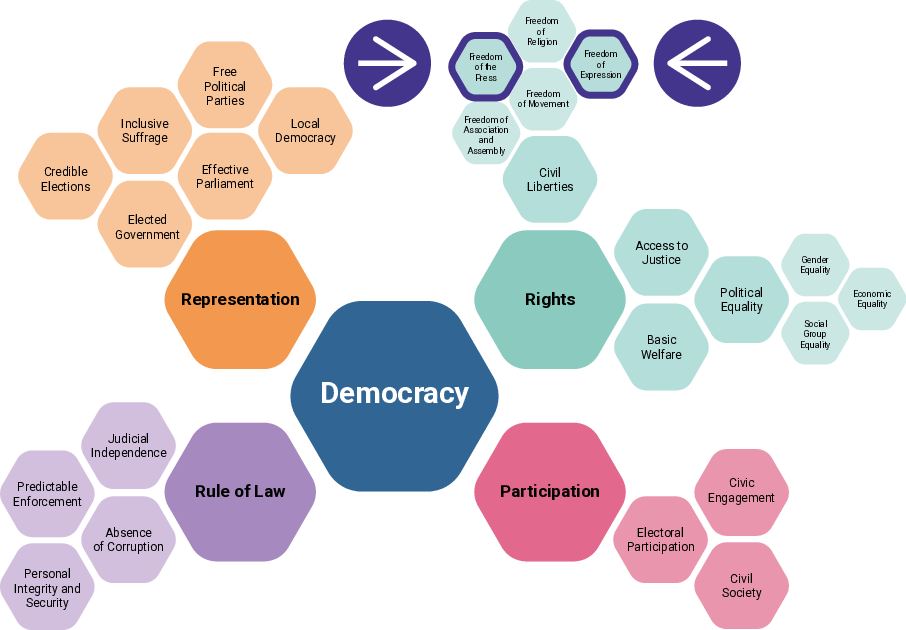

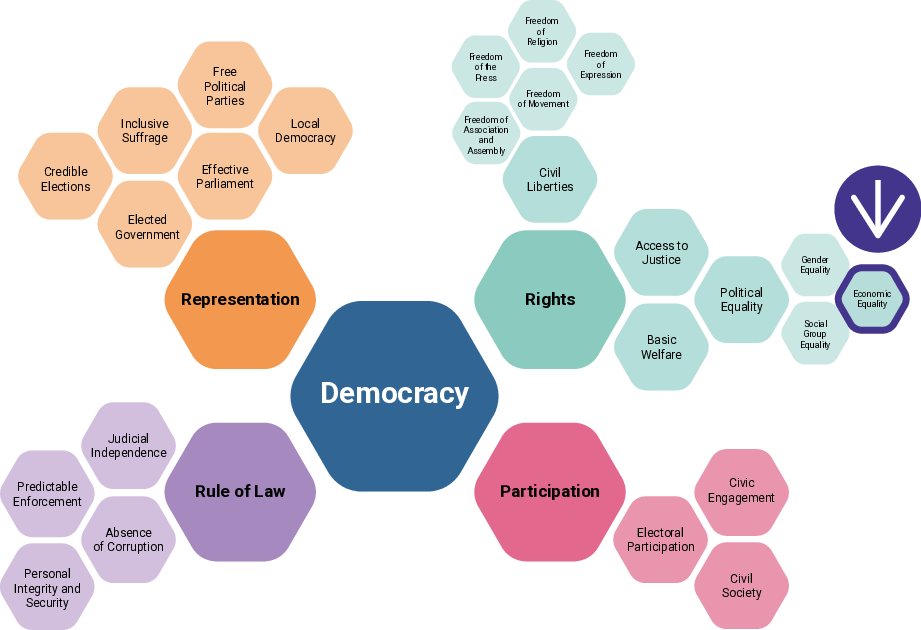

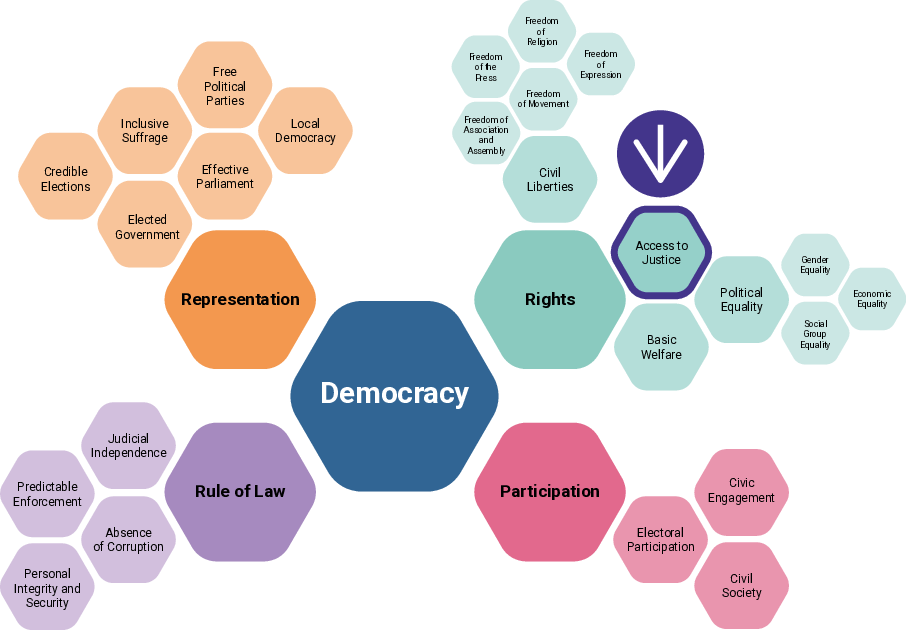

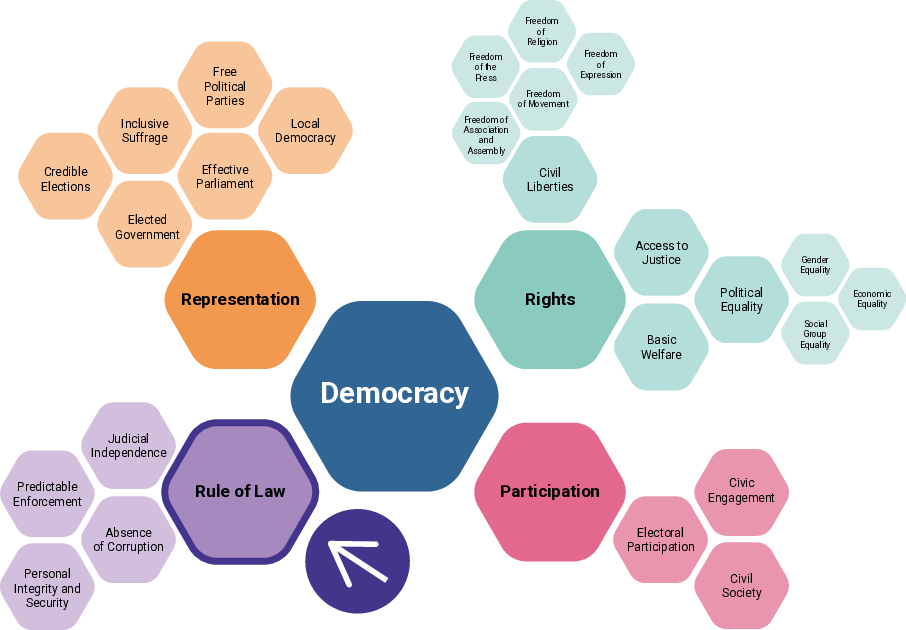

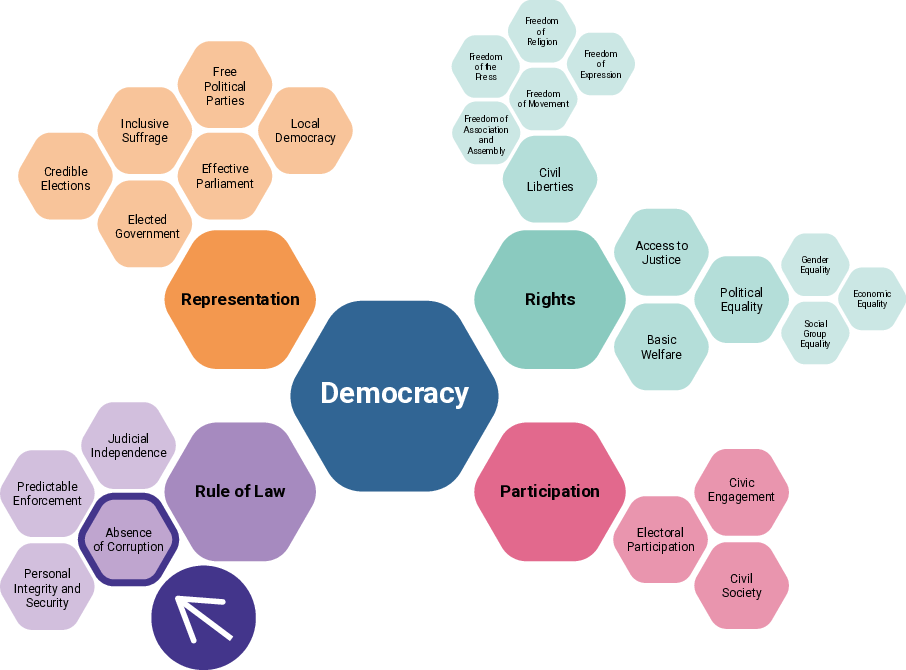

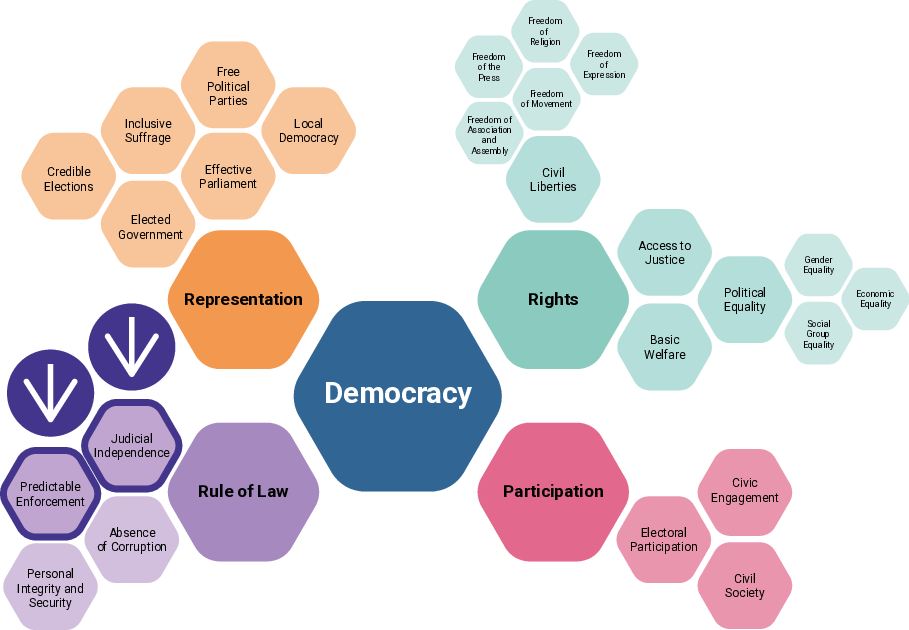

The Indices employ a hierarchical conceptual framework oriented around four core categories of democratic performance: Representation, Rights, Rule of Law and Participation (see Figure 0.1). Each category is subdivided into factors (such as Credible Elections or Judicial Independence) and subfactors (such as Freedom of Expression or Social Group Equality).

The GSoD Indices aggregate indicators from 22 data sources (see Box 0.1), which include observational data from United Nations agencies, expert-coded data from academic programmes and some data collected directly by International IDEA. The Indices are based on a total of 154 indicators. The result is a collection of 1,676,362 data points collected on 174 countries1 over 50 years.

Box 0.1. The Global State of Democracy Indices: Source data sets

| Data set | Data provider | Reference |

|---|---|---|

| Bertelsmann Stiftung’s Transformation Index (BTI) | Bertelsmann Stiftung | <https://bti-project.org> |

| Bjørnskov-Rode Regime Data (BRRD) | Bjørnskov and Rode | <https://sites.google.com/unav.es/martin-rode/home/data> |

| Child Mortality Estimates (CME) | UN Inter-agency Group for Child Mortality Estimation | <https://childmortality.org> |

| Civil Liberties Dataset (CLD) | Møller and Skaaning | <https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/0TKJWX> |

| Food and Agricultural Organization of the United Nations (FAO) Food Balances | Food and Agricultural Organization of the United Nations (FAO) | <https://www.fao.org/faostat/en/#data/FBS> |

| Freedom in the World | Freedom House | <https://freedomhouse.org/report/freedom-world> |

| Freedom on the Net | Freedom House | <https://freedomhouse.org/report/freedom-net> |

| Global Educational Attainment Distributions | Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation (IHME) | <https://ghdx.healthdata.org/record/ihme-data/global-educational-attainment-distributions-1970-2030> |

| Global Findex Database | World Bank | <https://data.worldbank.org> |

| Global Gender Gap Report | World Economic Forum | <https://www.weforum.org/publications/global-gender-gap-report-2024> |

| Global Health Observatory | World Health Organization (WHO) | <https://www.who.int/data/gho/data/themes/topics/indicator-groups/indicator-group-details/GHO> |

| Global Media Freedom Dataset (MFD) | Whitten-Woodring and Van Belle | <https://faculty.uml.edu//Jenifer_whittenwoodring/MediaFreedomData_000.aspx> |

| ILOSTAT | International Labour Organization (ILO), Department of Statistics | <https://ilostat.ilo.org> |

| International Country Risk Guide (ICRG) | Political Risk Services | <http://epub.prsgroup.com/products/icrg> |

| Lexical Index of Electoral Democracy (LIED) | Skaaning, Gerring and Bartusevičius | <https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/WPKNIT> |

| Political Terror Scale (PTS) | Gibney, Cornett, Wood, Haschke, Arnon and Pisanò | <http://www.politicalterrorscale.org> |

| Polity5 | Marshall, Jaggers and Gurr | <http://www.systemicpeace.org/inscrdata.html> |

| Standardized World Income Inequality Database (SWIID) | Solt | <https://fsolt.org/swiid> |

| United Nations E-Government Survey | UN Department of Economic and Social Affairs | <https://publicadministration.un.org/egovkb/en-us/Reports/UN-E-Government-Survey-2024> |

| Varieties of Democracy data set | V-Dem Project | <https://www.v-dem.net> |

| Voter Turnout Database | International IDEA | <https://www.idea.int/data-tools/data/voter-turnout> |

| World Population Prospects (WPP) | UN Department of Economic and Social Affairs Population Division | <https://population.un.org/wpp> |

A complementary source of evidence for this report is International IDEA’s Democracy Tracker, a qualitative data set that provides event-centric information on democracy developments in 173 countries, with a data series beginning in August 2022 and updated every month after that. The Tracker reports democracy-related developments that may signal significant advances or declines in a country’s democratic performance in a particular month, and monitors developing events that could signal that such a change is very likely in the next year (International IDEA 2025h). The Tracker has enabled this edition of the GSoD report to reflect key democratic trends through June 2025, offering additional depth to country-specific discussions, including cases where notable developments occurred after the December 2024 cut-off for the GSoD Indices data.

Some country examples featured in the report, such as those from the USA, are included based on the relevance of their democratic developments to broader regional or global patterns. The Tracker ensures that these examples are evidence-based and grounded in recent developments.

In addition to data, the report also draws on the subject matter and regional expertise of International IDEA’s staff at the Institute’s headquarters in Sweden, as well as the work of staff at regional and country offices across Africa and West Asia, the Americas, Asia and the Pacific, and Europe. The insights of International IDEA staff who are closely involved in democracy-building efforts help to contextualize the data and identify critical trends as they unfold.

Structure and approach of the report

This year’s report begins with a broad overview of trends at the global level, shining a light on the aspects of democracy that experienced the most change—positive and negative—comparing 2024 to 2019. Specifically, Part 1 of the report provides a description of what has changed within each category of democratic performance—Representation, Rights, Rule of Law and Participation. It uses country cases2 to draw out illustrative examples and highlight noticeable patterns. These descriptions are meant to serve not as exhaustive lists of the events that are driving change but as illustrations of the kinds of developments that explain what the data reflect. In most cases, the analysis illustrates advances and declines by referencing statistically significant changes that have occurred in comparison with five years earlier. When that is not the case, the specific interval is referenced.

Quantitative scores from the GSoD Indices for each category, factor and subfactor are also categorized into levels of performance. All the indices at the different levels have been normalized to range from 0 (lowest achievement) to 1 (highest achievement). If a country’s score exceeds 0.7, its performance is labelled ‘high’. Scores below 0.4 correspond to ‘low’ performance. Scores between 0.4 and 0.7 classify a country’s performance as ‘mid-range’.

Several countries currently experiencing armed conflict or war—such as Haiti, Palestine3, Sudan and Ukraine—have suffered declines in their democratic performance. These declines are closely linked to institutional disruption, political instability and deteriorating security conditions. The complexity and fluidity of such conflict-affected environments mean that existing democratic indices may not fully capture the on-the-ground realities. Further research is warranted to better understand how armed-conflict dynamics interact with democratic resilience or declines, and to assess the methodological limits of measuring democracy in such contexts.

In response to growing global migration and a resurgence of inward-looking policies, Part 2 of the report focuses on demonstrating why and how democracies can lead the way in responding to a world on the move. It explains how democracies and countries with democratic aspirations can foster inclusion by helping to facilitate political participation for non-resident nationals. This section of the report also includes a set of guiding questions for policymakers who are considering how to craft out-of-country voting policies in line with democratic values.

The first half of 2025 underscored the extent to which radical uncertainty remains a defining feature of the global context. The return of Donald Trump to the US presidency reflects this volatility, contributing to the erosion of long-held assumptions across multiple domains—from the economic impacts of tariffs, to the authority of supranational institutions responsible for protecting global peace and stability, to the inviolability of international borders among liberal democracies.

For actors genuinely concerned about democratic principles, recent developments have raised serious concerns about the state of global democracy. The USA—a country long regarded as a leading advocate for democracy worldwide—has, in 2025, significantly reduced both its diplomatic engagement and its financial support for international democracy assistance. These developments have contributed to a weakening of international democratization efforts. In less than six months, US domestic political institutions have also lost much of their symbolic sheen, increasingly serving as a reference point for executive overreach and offering more encouragement to populist strongman leaders than to pro-democracy hopefuls.

Between January and April 2025, International IDEA issued 20 alerts (twice as many as in any of the previous two full years), documenting instances in which the US Government has eroded and abolished the rules, institutions and norms that have shaped US democracy (International IDEA n.d.c). Examples include efforts to restrict academic freedom, criminalize protest activity, question the legitimacy of certified elections, selectively restrict media access to the executive and circumvent due process norms.

These developments have not yet been captured in full by the GSoD Indices due to the time lag, but they are well documented in the Democracy Tracker and illustrate a rapid rate of change. Some observers have described these developments as a ‘presidential coup’ in the USA, warning that the country lies at the ‘cusp of autocracy’ (Center for Systemic Peace n.d.).

While these recent developments have raised alarms in many quarters, some academic analysts and civil society actors see the US case as a reminder of the danger inherent in assuming that the work of democracy is ever done. The political scientist Adam Przeworski (2025), for example, noted that, in apparent contradiction to decades of accepted wisdom, the combination of wealth and a history of peaceful political transitions may foster a false perception of democratic consolidation. This, in turn, can lead to reduced vigilance against authoritarianism and weaker societal resistance to democratic erosion.

Perspectives outside the Western democratic tradition have often been more measured, with some observers identifying the current moment as an opportunity for new voices, perspectives and influences on the shape of democracy—perhaps even the chance for a post-liberal model with resonance in regions beyond the West (Koelble and Lipuma 2008; Schmitter 2018). The domino effect of US developments—particularly the deprioritization of democracy promotion in parts of Europe (Carothers and Stuenkel 2025; Farinha 2025; Youngs 2025)—has also elicited renewed interest in democratic resilience (Raad van State 2024; Council of the European Union 2025)—the idea that democratic systems are uniquely equipped to weather crises, uncertainty and change.

1.1. Migration, inclusion and democracy

Global migration has emerged as a key factor contributing to the current climate of uncertainty (Casas Zamora 2024), raising complex questions about citizenship, belonging, the universality and equality of rights, and what it means to be an inclusive, resilient democracy today. The scale of migration continues to grow, with the latest data showing that 304 million people are international migrants—three times the estimate in 1970. Today, this figure represents 3.7 per cent of the world’s population (UNDESA 2025).

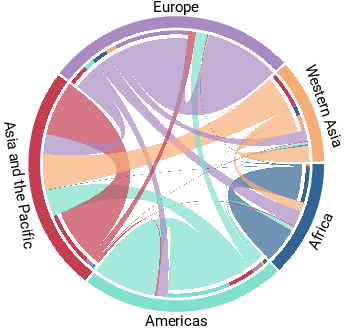

Figure 1.1 uses 2024 data from the UN Department of Economic and Social Affairs (UNDESA) to illustrate global migration patterns, with regions defined according to the GSoD framework. Contrary to many commonly held assumptions, the data show that most migration happens within, not between, regions. This pattern is particularly evident in the strong inward and outward flows (originating from the base), within each region, shown as wide colour-coded bands anchored at the regional bases. For example, the flow from Africa to Europe includes a purple band marked with blue on the outer rim of the circle, indicating migrants moving from Africa to Europe—yet this is just a fraction compared with the populations migrating within either region. Neighbouring bars at the European base show migrants arriving from the Americas (green), Asia and the Pacific (red), West Asia (gold) and Europe itself (purple).

Data from the International Organization for Migration listing the world’s top five country-to-country migration corridors (as of 2024) confirm this trend. All five corridors are intraregional or between neighbouring countries: (a) Mexico to the USA; (b) Syria to Turkey; (c) Ukraine to Russia; (d) India to the United Arab Emirates; and (e) Russia to Ukraine (McAuliffe and Oucho 2024; note that the data reflect total numbers of migrants regardless of the cause of movement).

Although migration has significant implications for democracy, some of the most well-known democracy assessment frameworks (such as those by Freedom House, International IDEA and V-Dem) do not have specific indicators that systematically measure how institutions include or exclude immigrants and emigrants (as distinct from resident citizens). As a result, migration-related problems are not reflected in quantitative measures of democracy such as the GSoD Indices. However, these issues are conceptually part of the broader GSoD Indices’ Social Group Equality subfactor, which measures inequality across social class and identity group, especially in terms of civil liberties and access to political power. It also tracks socio-economic and urban–rural exclusion. Since many migrants face more than one kind of disadvantage, looking at how countries perform on broader inclusion measures—like Social Group Equality—can help us understand how migration and democracy are connected. This link is explored further in Part 2 of this year’s report.

There was very little overall change in global terms in the Social Group Equality factor (comparing scores in 2024 to 2019). Where shifts did occur, they were predominantly negative. Only two countries (Moldova and Montenegro) registered improvements, while 16 countries experienced declines over the same period. The most severe deterioration occurred in Afghanistan, though five high-performing countries also saw negative changes (Canada, Luxembourg, the Netherlands, Slovenia and Uruguay).

Part 2 of this report examines the intersection of migration and democracy, and we ask how democracies can facilitate inclusive participation in a context where individuals increasingly maintain multiple identities and affiliations, often across national borders (Schlenker and Blatter 2013). The specific focus is on the question of emigrants’ participation, particularly through out-of-country voting.

While there are many drivers of migration4 and several categories of migrants that are based on those drivers, such classifications are generally more relevant to analysis that focuses on migrants’ rights in destination countries, where they are immigrants. In contrast, the analysis in Part 2 focuses on participation in migrants’ countries of origin, where the reasons for and contexts of their departure have less impact on the laws and mechanisms their home countries design (or fail to design) to facilitate their continued political participation. Accordingly, the analysis does not differentiate between various kinds of emigrants; instead, it focuses only on whether or not these emigrants can vote from abroad.

Global patterns show that democracy around the world continues to weaken. In 2024, 94 countries—representing 54 per cent of all countries assessed—suffered a decline in at least one factor of democratic performance, compared with their own performance five years earlier. In contrast, only 55 countries (32 per cent) advanced in at least one factor over that period. As Figure 2.1 illustrates, this represents an almost 8-percentage-point increase in the number of declines and a 2-point increase in advances compared with the previous year’s patterns (changes between 2018 and 2023).

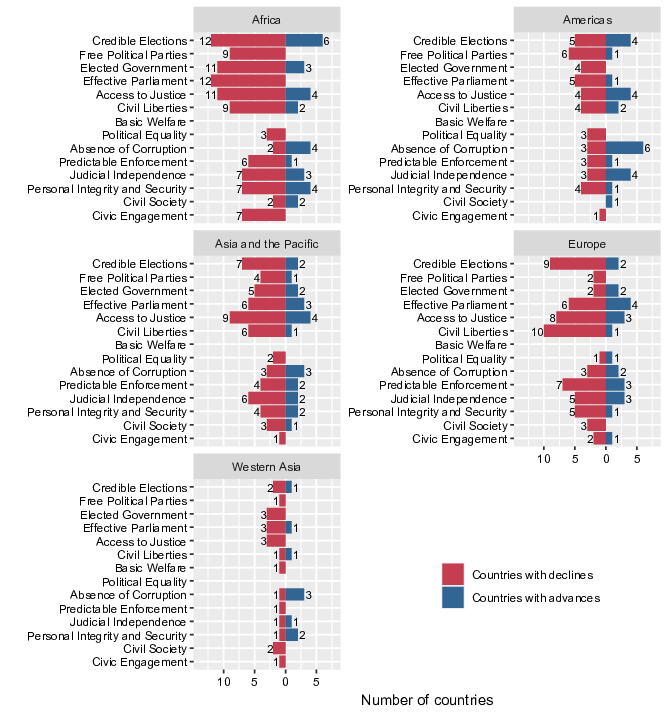

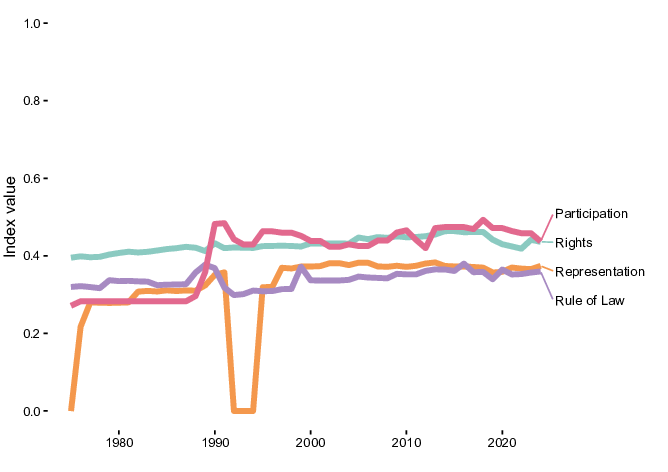

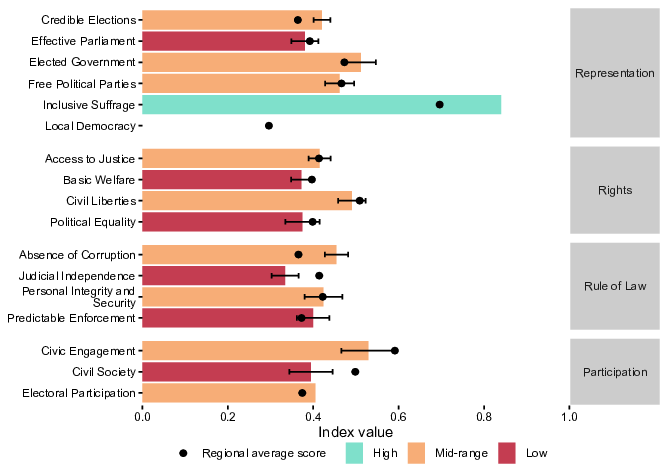

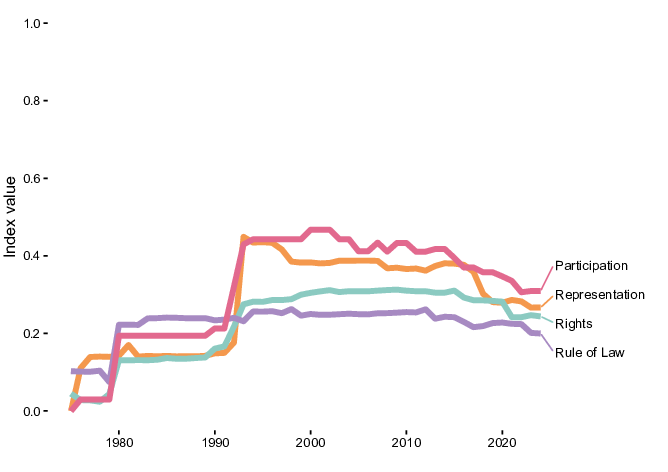

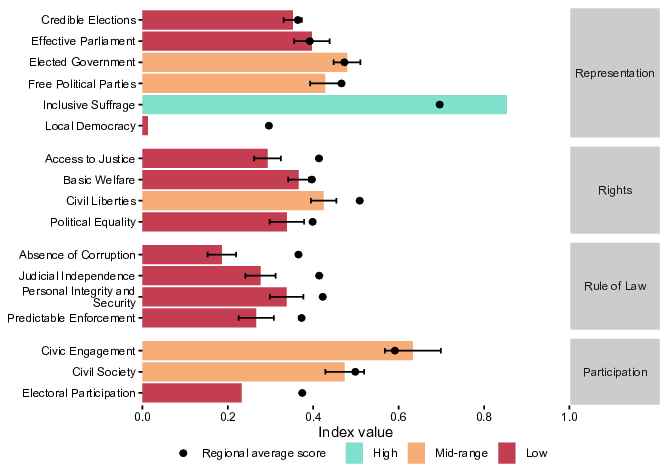

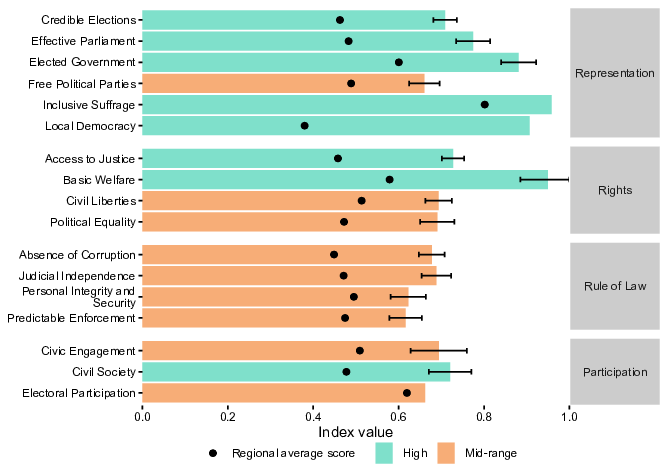

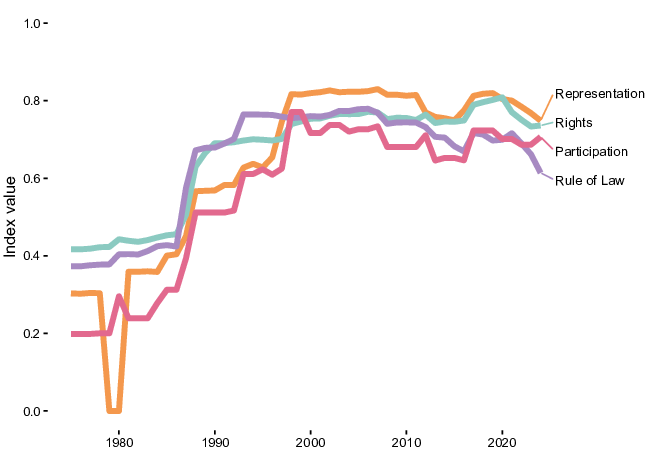

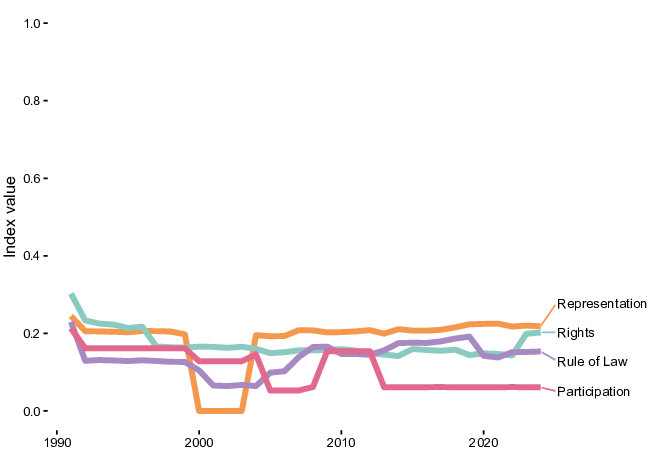

All regions experienced some degree of change in democratic performance (see Figure 2.2). African countries accounted for the largest share of global declines, with 33 per cent, followed by Europe, with 25 per cent. Asia and the Pacific and the Americas accounted for a smaller share of overall deterioration (20 per cent and 16 per cent, respectively), with West Asia, already the lowest-performing region globally, comprising the smallest portion (6 per cent).

These regional patterns of decline, however, were not all unidirectional. Countries in Africa and the Americas recorded the highest share of advances (24 per cent each of all advances), while Europe and Asia and the Pacific saw smaller shares of global progress (23 per cent and 21 per cent, respectively). West Asian countries accounted for 8 per cent of all improvements (see Figure 2.2 for a breakdown of changes at the factor level in each region).

Beneath the global shifts in democratic performance lies a more subtle but important trend—stability. Comparing 2024 to 2019, every country in the data set maintained stable performance in at least one factor of democratic quality.

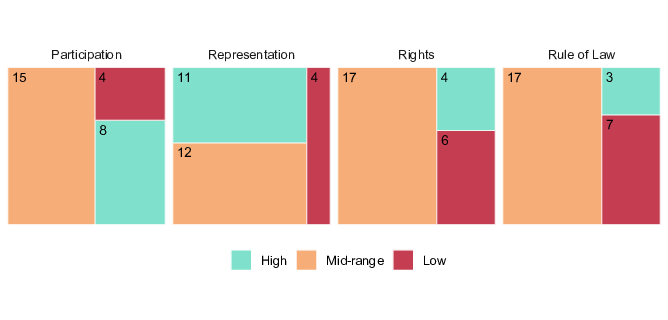

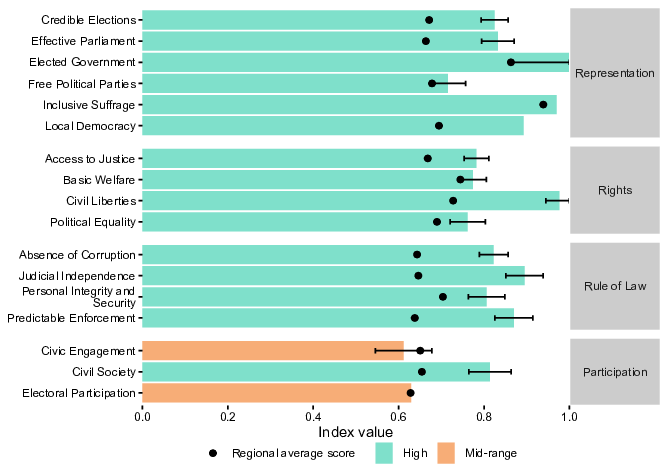

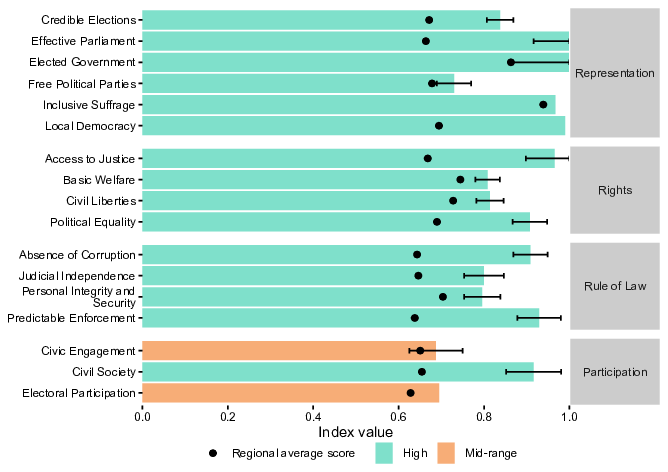

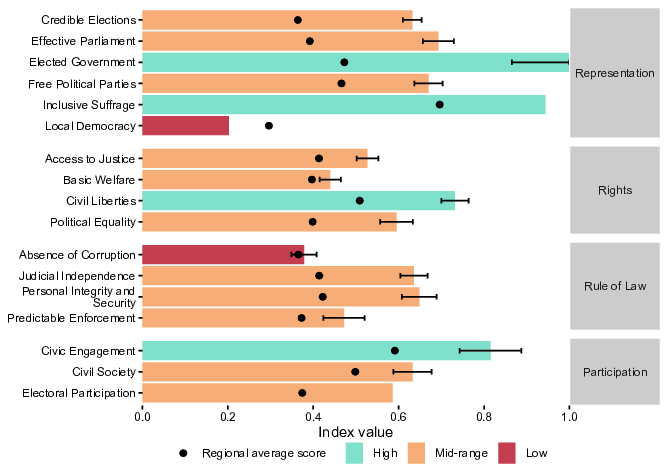

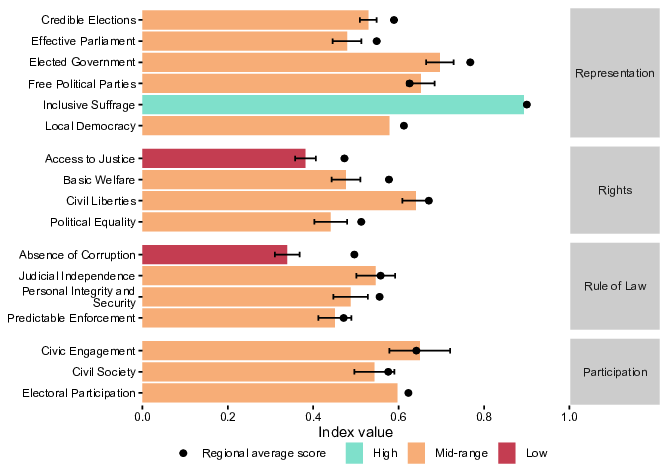

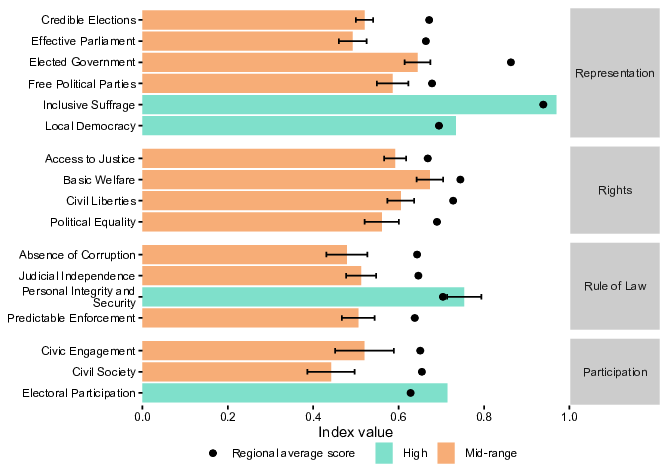

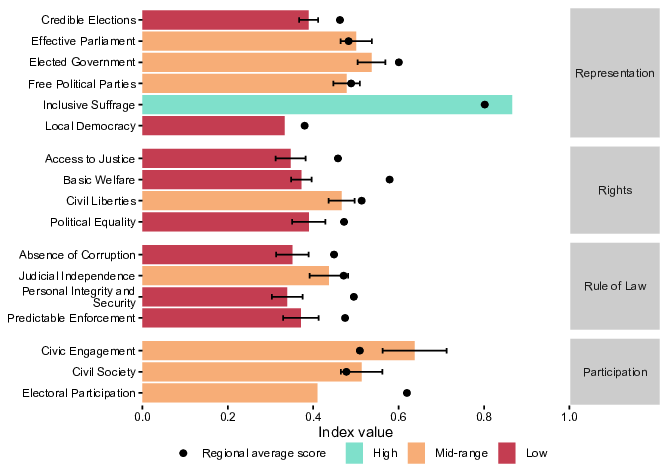

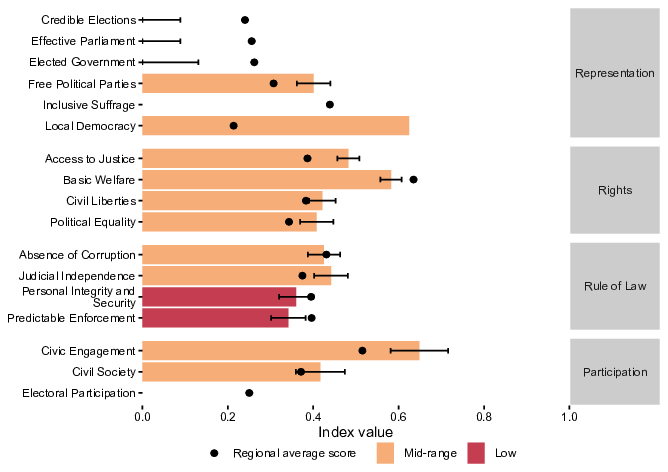

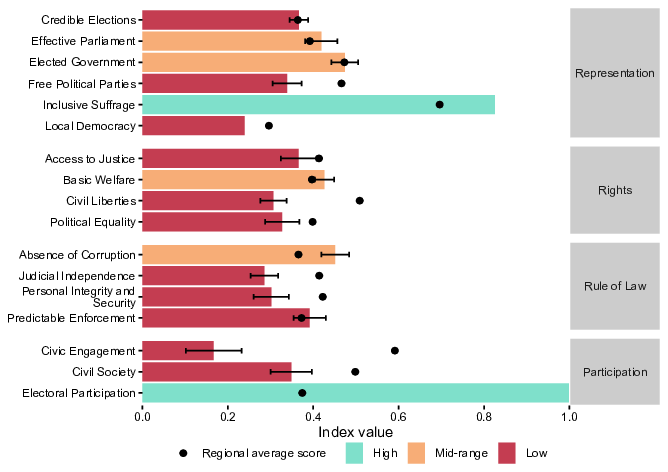

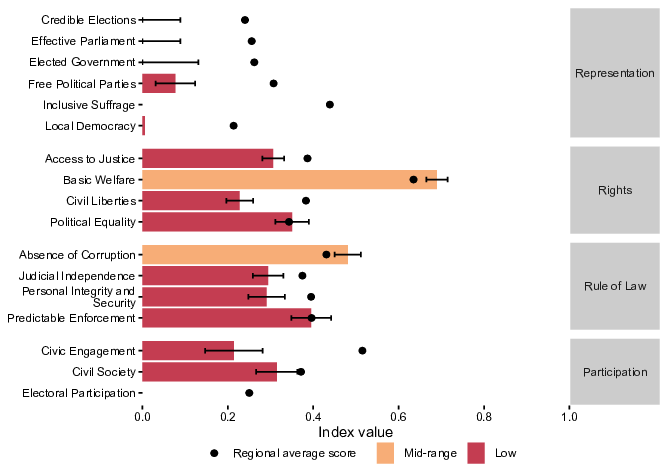

Among the four categories, country performance was strongest in Representation, with 47 countries (27 per cent) achieving high scores in 2024. Performance was weakest in Rule of Law, with 71 countries (41 per cent) falling into the low-performance band (see Figure 2.3 for a breakdown of the number of countries in each performance band at the category level).

2.1. Global declines and advances

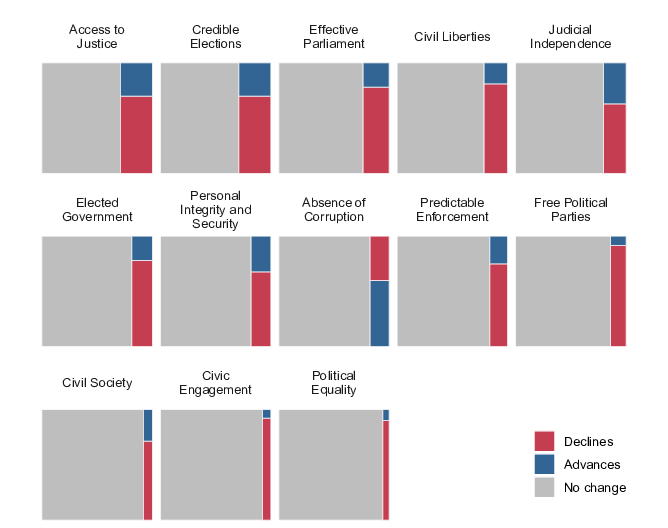

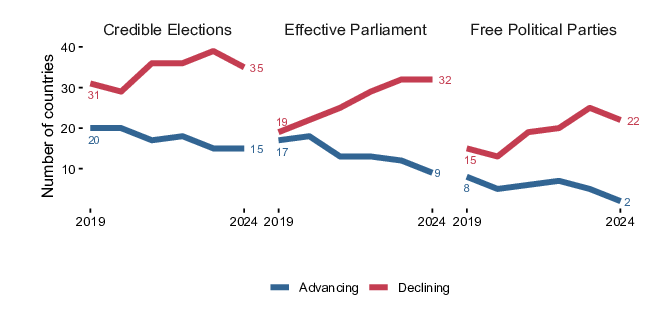

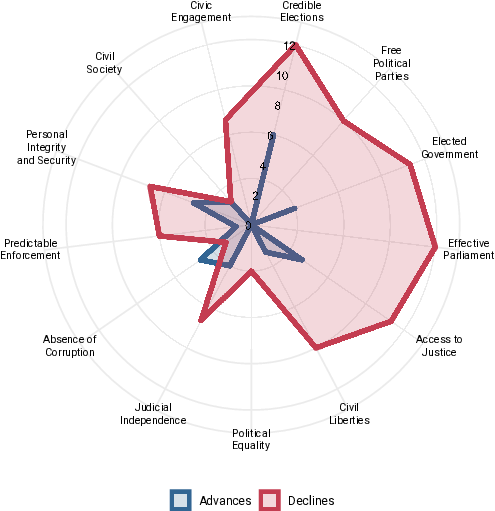

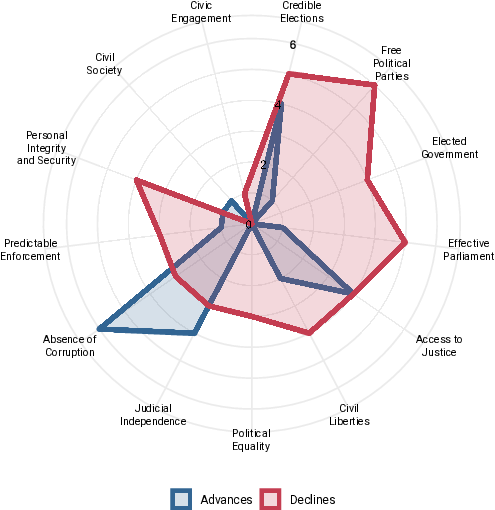

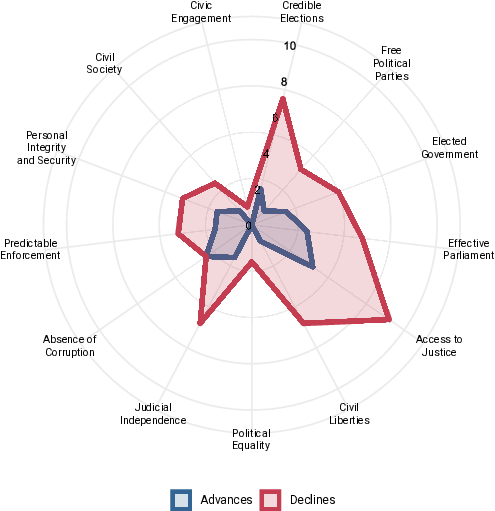

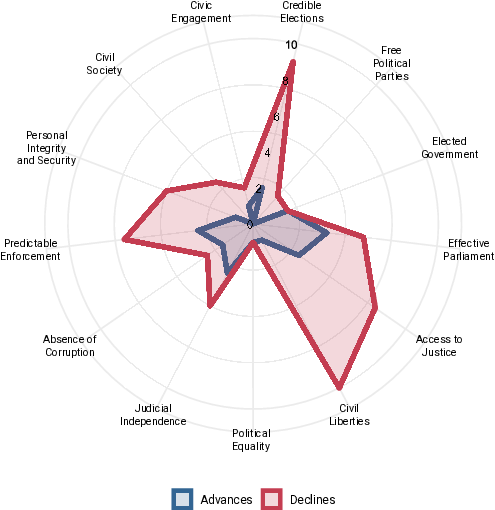

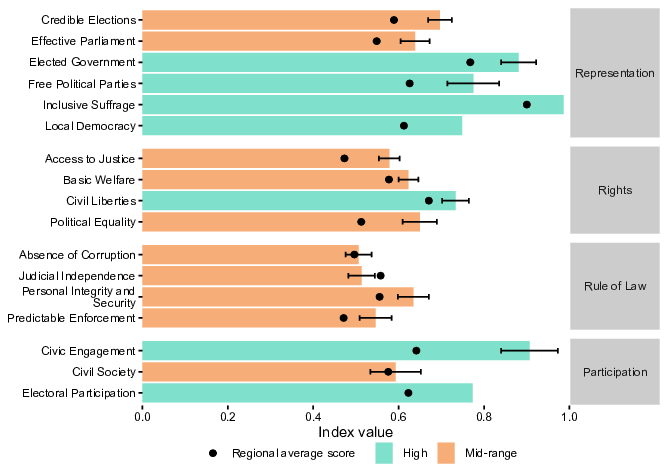

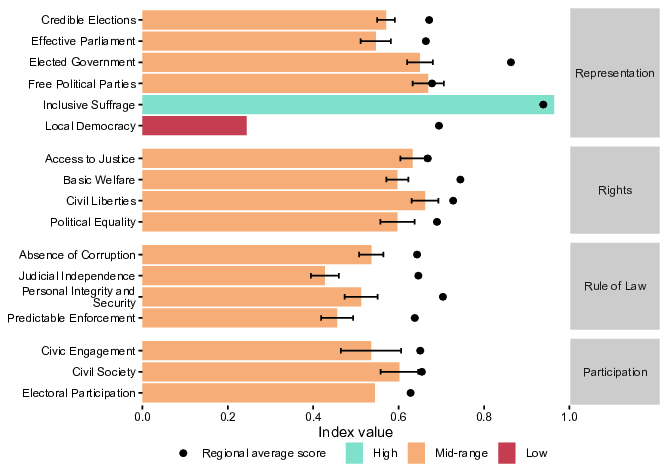

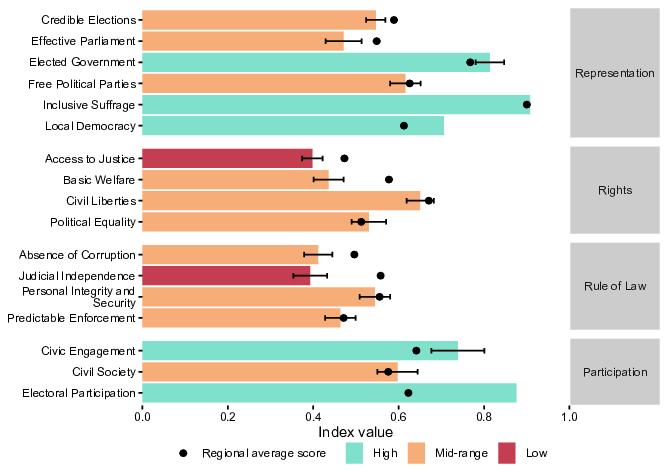

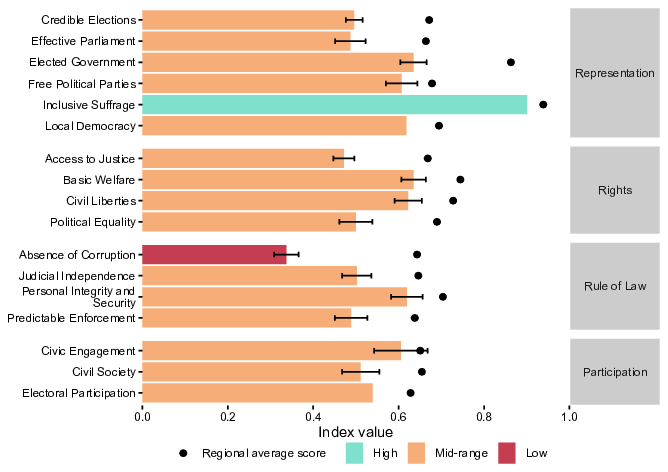

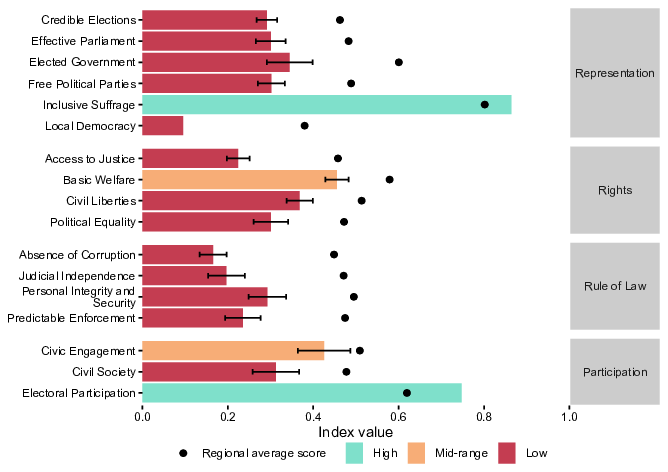

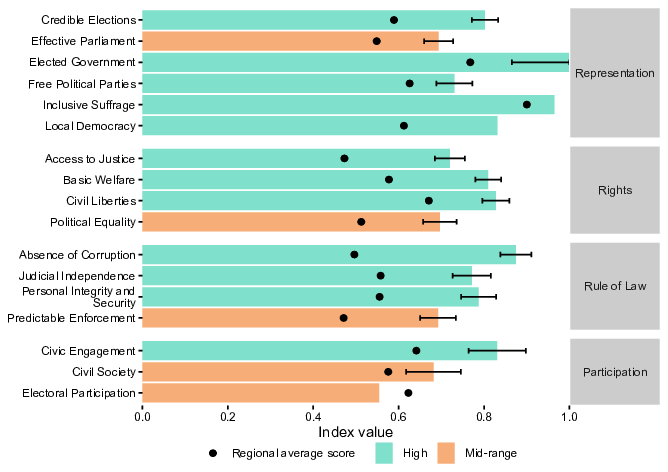

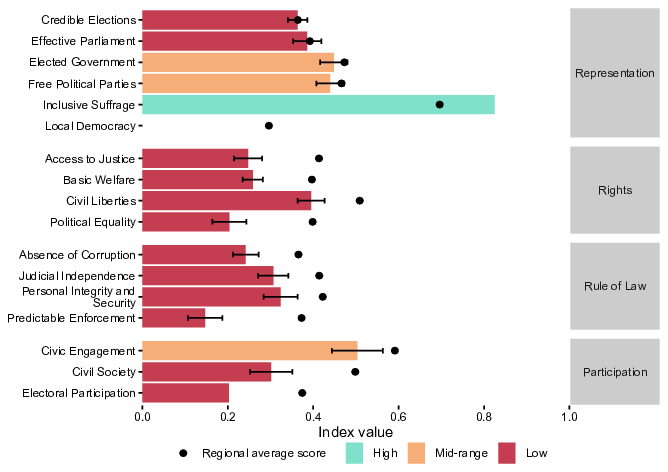

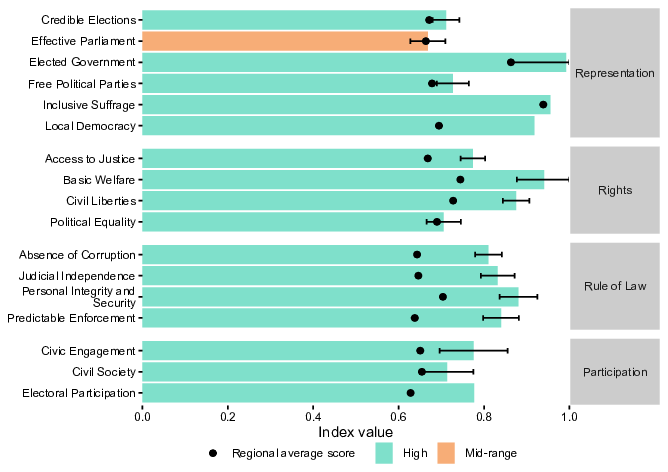

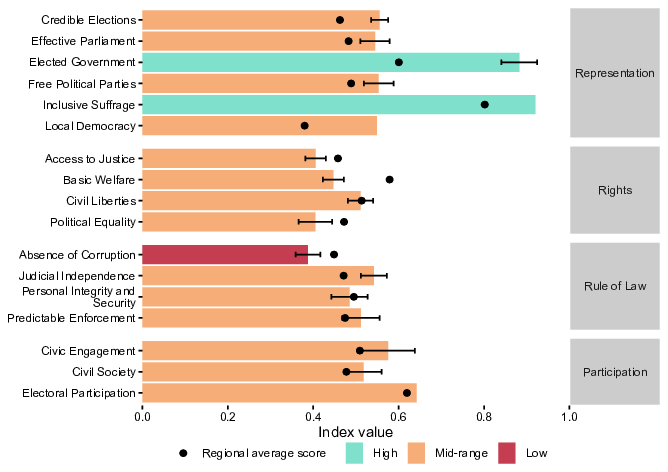

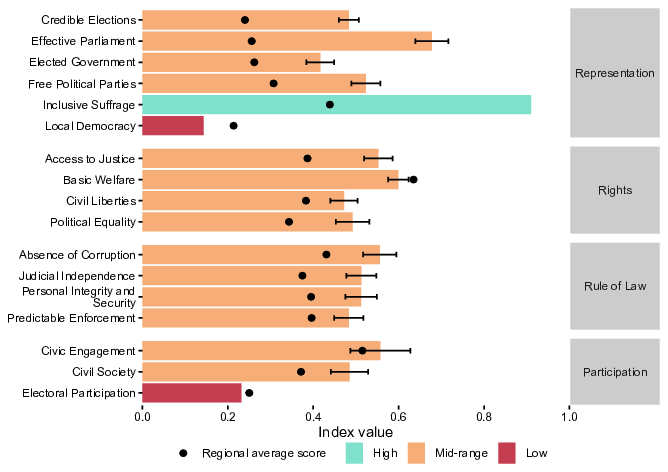

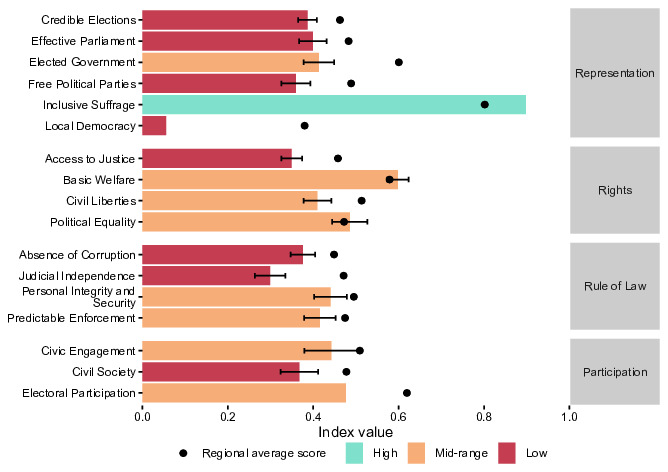

Declines at the factor level have been most concentrated in the categories of Representation, Rights and Rule of Law (see Figure 0.1 for an overview of how we measure democratic performance). Despite countries’ relatively strong overall performance in Representation, numerous declines were seen in Credible Elections and Effective Parliament (see Figure 2.4 for an overview of advances and declines at the factor level).

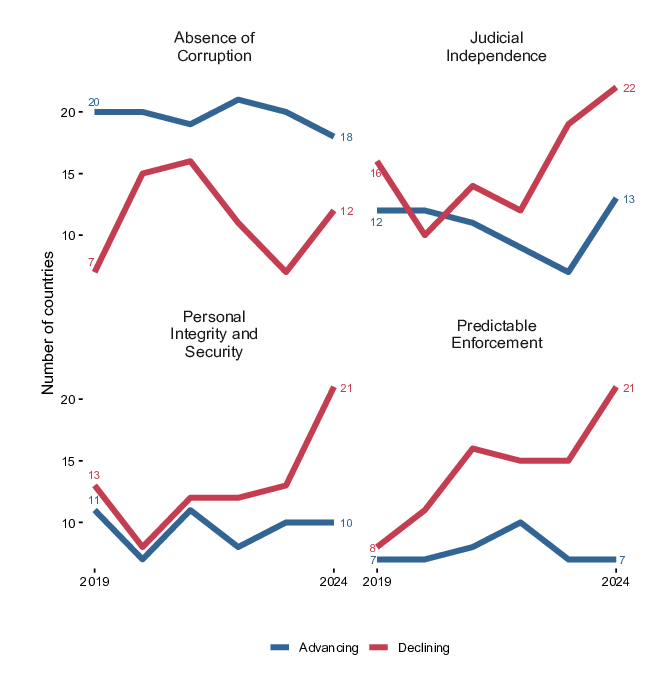

Within Rights, Civil Liberties was one of the factors that saw the broadest declines, with the most significant impacts seen in Freedom of the Press, followed by Freedom of Expression, Economic Equality and Access to Justice. Performance in Freedom of the Press declined in 43 countries, nearly one quarter (24.9 per cent) of those covered, marking the broadest decline in this factor since the beginning of our data set (1975) (see Box 2.1 for more details). Declines within the Rule of Law category were most concentrated in Judicial Independence, though Predictable Enforcement and Personal Integrity and Security were almost equally affected.

Box 2.1. Global declines in Freedom of the Press

Global regression was most severe in Freedom of the Press, with 43 countries experiencing declines when comparing 2024 to 2019. This is the broadest decline in this factor since the beginning of the GSoD Indices data set (1975). Performance in Freedom of the Press deteriorated across all regions, in 15 African and 15 European countries, as well as 6 countries each in the Americas and Asia and the Pacific. One country in West Asia also saw a decline. While the large majority of the countries experiencing declines were mid-range performers, four countries were in the high-range band (Finland, Portugal, Sweden and Uruguay).

The severity of the downturn in performance in this factor is reflected in the findings of the 2025 World Press Freedom Index, which noted that the global state of press freedom was categorized as a ‘difficult situation’ for the first time in the history of the Index. In 2025, the Index’s economic indicator, which measures ownership concentration, pressure from advertisers and financial backers, and the restriction or opaque allocation of public aid, fell to its lowest point yet (Reporters without Borders 2025).

The diversity of contexts that are experiencing this pattern can be seen from two examples—New Zealand and Palestine. In New Zealand, a media crisis has been marked by the shrinking of the press landscape. In 2024, the television and online news company Newshub shut down, leaving the country with only one television news service, the state-owned broadcaster TVNZ, which also reduced its news programming and staff. Media has become severely concentrated, as 78.5 per cent of journalists work for one of five employers (Reporters without Borders n.d.). Since October 2023, nearly 200 journalists have been killed, and Israel has imposed a blockade on the Gaza Strip for over 18 months (Reporters without Borders 2025). The treatment of Al Jazeera provides an example of the environment for media in the region. Between 2024 and 2025, Al Jazeera was targeted by both Israel and the Palestinian Authority, which have suspended the media outlet’s operations over alleged national security concerns and tensions over its coverage of certain events (International IDEA 2024z).

Twelve countries across all regions experienced significant advances in Freedom of the Press (comparing 2024 scores to 2019). Most of these were in the Americas (Bolivia, Brazil, the Dominican Republic and Honduras) and Europe (Bulgaria, Czechia, Montenegro and Poland). Only one country (Zambia) in Africa saw improvements, and there were two in Asia and the Pacific (Fiji and Sri Lanka) and one in West Asia (Syria). Syria was the only low-performing country to have seen any improvement in this factor. Brazil, Czechia and Poland moved from mid-range to high performance between 2019 and 2024.

The three largest declines in Freedom of the Press were seen in Afghanistan, Burkina Faso and Myanmar, all low-performing contexts that have been marked by violence and undemocratic transfers of power. The fourth-largest decline took place in South Korea, a country that fell from high to mid-range performance in this subfactor between 2019 and 2024. There, the media has faced multiple challenges over the past several years. Examples include the cancellation of a well-known investigative journalist’s daily political programme, a spike in defamation cases initiated by the government and its political allies against journalists, and raids on journalists’ residences (Civicus 2024). Such incidents continued in 2024, with the establishment of a special investigative prosecutorial team targeting journalists for defamation (Lee, Cho and Jo 2023; Jang 2024). After a tumultuous year that included the now-former president’s declaration of martial law and his subsequent impeachment, a snap election in June 2025 brought a new administration to power. It remains to be seen how this transition may affect the country’s media landscape in the coming months.

Although advances were less frequent overall within the Rights category, Freedom of Expression stood out as a notable exception. Comparing 2024 to 2019, 20 countries (12 per cent of those assessed) registered improvements in this factor, and they were fairly evenly distributed across the regions. Still, declines in Freedom of Expression were also notable, impacting 39 countries around the world.

Chile recorded the largest improvement in Freedom of Expression (comparing 2024 scores to 2019), due in part to landmark draft legislation aimed at enhancing the safety of journalists and others in the field of communications, as well as their families. If approved by the legislature, the bill would introduce several novel features, including a broad definition of ‘aggression’ that goes beyond physical aggression to include digital harassment and surveillance (Pagola 2023; Gobierno de Chile 2024).

Progress was also observed in other areas of democratic performance worldwide, particularly in Absence of Corruption, Access to Justice and Credible Elections. Botswana recorded the largest improvement in Credible Elections (comparing 2024 scores to 2019), with observers noting an increased number of polling stations both in the country and abroad, the official designation of two public holidays (on the day of and day after polling) to enable the maximum number of voters to participate and pre-election debates organized by the media. While observers also cited challenges—for example, with communication and the appointment of election authorities—they commended Botswana for holding transparent elections. The 2024 election was a landmark in the country’s post-independence history, marking the end of the Botswana Democratic Party’s 58-year tenure in power (ECF–SADC 2024a; International IDEA 2024af).

2.2. Representation

In the GSoD Indices, Representation is an aggregate measure of the extent of representative democracy, building from component measures of credible elections, inclusive suffrage, freedom to organize through political parties, the effectiveness of the legislature and the practice of democracy at the local level.

Representation symbolizes what is often considered to be the core of democracy, including the mechanisms through which the people choose their leaders and representatives (elections and political parties), and the institutions (legislatures) responsible for translating the expression of public will into actionable policy.

Table 2.1 highlights the top 10 countries in Representation performance for 2024, showing both regional diversity and year-on-year movement in the rankings. Germany, Denmark and Norway continue to lead globally. It is also noteworthy that Mauritius’s performance in Representation experienced a notable improvement, climbing 23 places in the rankings.

| 2024 rank | Country | 2023 rank | Change 2023–2024 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 |  | Germany | 1 | 0 |

| 2 |  | Denmark | 3 | +1 |

| 3 |  | Norway | 2 | -1 |

| 4 |  | Costa Rica | 4 | 0 |

| 5 |  | Chile | 5 | 0 |

| 6 |  | Sweden | 6 | 0 |

| 7 |  | Finland | 10 | +3 |

| 8 |  | Italy | 13 | +5 |

| 8 |  | Netherlands | 9 | +1 |

| 10 |  | Estonia | 12 | +2 |

These top performers stand in contrast to broader global trends in 2024, which point to the lowest global performance in Representation since 2001. Category-level declines were recorded in 21 countries, outnumbering advances by a ratio of 7 to 1, with deterioration observed in all regions. Most declines impacted low-performing countries, but mid-range- and high-performing countries were also affected.

Comparing 2024 to 2019, improvements in Representation were recorded in just three countries—mid-range-performing Honduras and Montenegro and high-performing Latvia. Some of the advances in Honduras were associated with the 2021 elections, which European Union observers described as competitive and calm. Other markers of improvement included a more reliable voter register and high turnout (European Union Election Observation Mission 2022).

At the factor level, Credible Elections and Effective Parliament continued to see the broadest declines, impacting 35 countries (20 per cent) and 32 countries (19 per cent), respectively. These declines occurred across all levels of performance and in every region of the world. Africa experienced the highest concentration of declines in these two factors, with nearly one in four countries (23 per cent) exhibiting a significant drop in either Credible Elections or Effective Parliament. In no region did the number of advances outweigh the number of declines in any factor of Representation. Figure 2.5 illustrates the trends over time for advances and declines in the factors of Representation.

Despite widespread declines in related factors, elections continue to hold unique power and promise as a means of democratic renewal. Comparing 2024 to 2019, 24 countries around the world (14 per cent) experienced improvements in Credible Elections or Effective Parliament.

Notable examples include Brazil and Poland, where the election of new governments (in 2022 in Brazil and 2023 in Poland) brought an end to years of consistent democratic deterioration that included executive aggrandizement, the undermining of the rule of law and the independence of the courts, constraints on the media and restrictions in the space for civil society. In Poland’s case, this period was also characterized by a strained relationship with the EU, which withheld millions of euros in funding over concerns regarding the deliberate weakening of the rule of law (Carothers and Carrier 2025).

Since the most recent elections, both countries have recorded measurable improvements. Brazil recorded advances in 10 factors related to the quality of democracy between 2022 and 2024, while Poland improved in 6 factors between 2023 and 2024. Although both contexts remain challenging, due in part to the divided government in both countries, there has been progress in reversing several non-democratic policies of the past. For example, both countries have taken steps to seek accountability for previous rule-of-law violations and to expand civic space (International IDEA 2024s, 2025j). In Poland, a key development to monitor will be the role of the newly elected president, aligned with the opposition, whose veto power may shape the reform trajectory going forward.

Credible Elections

The Credible Elections index aggregates indicators that measure the extent to which elections for national representative political office are free from irregularities, such as flaws and biases in the voter registration and campaign processes, voter intimidation and fraudulent counting.

As of the end of 2024, data from the GSoD Indices showed that 35 countries (20 per cent of those covered) had recorded declines in Credible Elections compared with 2019. Countries with declines were found at all levels of performance, from higher performers, such as Georgia and South Korea, to low-performing contexts, such as Mozambique and Pakistan.

Following the 2024 elections super-cycle year, a few countries stand out for sharp declines between 2022 and 2024. Georgia’s 2024 legislative elections were marked by controversy, with election observers pointing to irregularities that included alleged intimidation, ballot-box stuffing and vote buying. The former president, alongside civil society and members of the opposition, rejected the results, and opposition lawmakers boycotted the legislature’s inaugural session. Mass protests continued throughout the year (International IDEA n.d.c; Megrelidze 2024).

Mozambique also experienced a significant decline, falling from mid-range to low performance in this factor between 2022 and 2024. The country’s October 2024 election was controversial, with observers raising concerns about an inflated voter roll, ballot-box stuffing, irregularities in vote counting and tabulation, and the management of complaints and appeals. The post-election period was marred by violence; police used live ammunition on protesters, and hundreds perished. Talks between the government and opposition leaders were initiated in March 2025 to resolve the impasse, with an agreement reached in April 2025 (Budoo-Scholtz 2025; International IDEA 2025o).

These disputes are emblematic of a broader trend identified in previous editions of this report, and they signal both danger and promise (International IDEA 2024a). The people remain the ultimate check on power, but the connection between their voice and authorities’ actions, especially when elites are unwilling to let go of power, can often be tenuous. In the wake of the 2024 super-cycle year of elections, four countries experienced improvements in indicators of Credible Elections. All of these were in Africa: Botswana, Chad, Mauritius and South Africa. In Mauritius, observers noted the credible work of the EMB, a peaceful electoral environment and smooth and timely operations at most polling stations (ECF–SADC 2024b).

Effective Parliament

The Effective Parliament index aggregates indicators that measure the presence of opposition parties, legislative investigations and questioning of officials, as well as broader measures of executive oversight and executive constraints.

Nearly one in five countries has experienced a decline in Effective Parliament, signalling problems with legislative checks on executive power. Comparing 2019 to 2024, 32 countries (19 per cent) registered declines, while only 9 (5 per cent) showed improvements. Among the countries with declining performance, Japan was the only high-performing country; the remainder were split almost evenly between low-performing and mid-performing contexts (for two examples, see Box 2.2). Several of the lowest performers experienced a coup d’état or other undemocratic transfer of power, while others continued to be affected by ongoing violent conflicts: examples include Afghanistan, Burkina Faso, Gabon, Guinea, Haiti, Mali, Niger, Myanmar and Syria. Others, such as El Salvador, Kuwait, Russia and Venezuela, do not have effective legislatures because they have been co-opted by executives or abolished. Mid-range performers with deteriorating parliamentary effectiveness are found across all regions and include countries as diverse as Kyrgyzstan, Lebanon, Mauritius, Paraguay and Slovakia. These declines often coincide with setbacks in other areas of their democratic performance, including in varied factors of Representation, Rights and Rule of Law.

Box 2.2. Effective Parliament and political exclusion in Kuwait and Qatar

In small Gulf states such as Kuwait and Qatar, citizens make up a minority of the total population—approximately 30 per cent in Kuwait and just 12 per cent in Qatar (Gulf Research Center n.d.). Both countries maintain a clear distinction between so-called original citizens—defined as descendants of families residing in Kuwait before 1920 and in Qatar before 1930—and naturalized citizens,5 who face restrictions in access to public-sector employment, social benefits and political participation6 (Ali and Cochrane 2024).

In 2024, separate developments in Kuwait and Qatar highlighted this citizenship divide and the relatively weak power of the legislature (both countries have a score of 0 in Effective Parliament).

In Kuwait, amendments to the 1959 Nationality Law expanded the state’s powers to revoke citizenship and retroactively ended automatic naturalization for foreign wives7 (International IDEA 2024x; Benswait 2025). These changes coincided with the Emir’s May 2024 dissolution of parliament and suspension of constitutional safeguards (International IDEA 2024m). Between August 2024 and March 2025, around 42,000 people lost their citizenship (The New Arab 2025). Women who had acquired nationality through marriage were severely impacted. Despite the establishment of a new appeals committee (Arab Times Kuwait 2025), the system lacks judicial oversight, functioning as an administrative body under the Council of Ministers. In a televised address, the Emir framed the campaign as a way of ‘purifying’ the national identity and ‘returning the country to its original people’ (Al-Bilad 2025; ATV Kuwait 2025).

In Qatar, a November 2024 referendum ended legislative elections and reverted the Shura Council (the country’s advisory legislative chamber) to a fully appointed body (International IDEA 2024ai). The Emir argued that this change was needed to prevent identity-based divisions within society, following tensions sparked by the 2021 elections, in which naturalized citizens were excluded from voting rights (Al-Hajri 2021; The Shura Council 2024). The referendum passed with 91 per cent approval and an 84 per cent turnout (Qatar News Agency 2024). Through this measure, Qatar revoked voting rights for original citizens rather than extending suffrage to naturalized citizens, thus maintaining their political exclusion (Postigo Sánchez 2024).

Nine countries experienced improvements in their performance with regard to the Effective Parliament factor (comparing 2024 scores to 2019). These include high-performing Brazil, Czechia, France and Poland, as well as mid-range-performing Fiji, Jordan, Montenegro, Papua New Guinea and Thailand.

Brazil, whose score in Effective Parliament increased the most between 2019 and 2024, is a notable example of how the legislature can assert its role in holding the executive to account. In October 2023, a legislative committee accused former President Jair Bolsonaro and his allies of crimes in connection with January 2023 riots. The committee characterized the events as a premeditated coup attempt and recommended that the attorney general pursue charges against Bolsonaro that included political violence, criminal association, abolition of the rule of law and an attempted coup. While the legislative committee lacks prosecutorial authority, its recommendations contributed to formal police charges and the Supreme Court’s unanimous vote to accept the charges. Bolsonaro and his allies are now due to stand trial (International IDEA 2023e, 2024ag).

2.3. Rights

In the GSoD Indices, the Rights category is made up of liberal and social rights that support both fair representation and accountability. It is built upon four component measures of Access to Justice, Civil Liberties (including Freedom of the Press, Freedom of Expression, Freedom of Association and Assembly, Freedom of Religion and Freedom of Movement), Basic Welfare and Political Equality (including Gender Equality, Social Group Equality and Economic Equality).

A small group of countries continues to lead on rights protections. As illustrated in Table 2.2, Denmark, Switzerland and Germany held the top three positions in 2024, maintaining stable performance, while countries such as Norway, Ireland and Sweden registered notable improvements. These top performers represent the global high-water mark in safeguarding rights and freedoms.

| 2024 rank | Country | 2023 rank | Change 2023–2024 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 |  | Denmark | 1 | 0 |

| 2 |  | Switzerland | 2 | 0 |

| 3 |  | Germany | 3 | 0 |

| 4 |  | Luxembourg | 4 | 0 |

| 5 |  | Belgium | 5 | 0 |

| 6 |  | Norway | 14 | +8 |

| 7 |  | Finland | 8 | +1 |

| 8 |  | Ireland | 9 | +1 |

| 9 |  | Japan | 6 | -3 |

| 10 |  | Sweden | 11 | +1 |

Nevertheless, these countries remain exceptions to a broader pattern of decline. Comparing 2024 scores to 2019, significant erosion was seen in the Rights category, with category-level declines outnumbering advances by a ratio of 9 to 1; the sole advance was in Vanuatu. The steepest declines took place in low-performing Belarus and Myanmar, which are among the countries with the largest number of declines across many factors (in all categories) from 2019 to 2024. Declines have also been recorded, however, in mid-range contexts like Greece and Burkina Faso. Greece dropped from high to mid-range performance in Rights between 2023 and 2024 (though it remains close to the threshold for high-range status).

Declines were most common in Freedom of the Press, Freedom of Expression, Economic Equality and Access to Justice. The decline in Freedom of the Press, impacting nearly 25 per cent of countries, is the most widespread drop since the beginning of the data set in 1975. Approximately one in five countries also saw declines in Freedom of Expression (22 per cent of countries), Economic Equality (21 per cent) and Access to Justice (20 per cent) (see Figure 2.6). This deterioration was reflected across all regions, with Africa and Europe accounting for the largest share of declines in each of these factors.

At the same time, however, a smaller number of countries made notable gains, demonstrating that positive trajectories are still possible, particularly in mid-range- and high-performing contexts. Advances were most common in Freedom of Expression, where 20 countries (12 per cent) saw progress. With the exception of two low-performing countries (Bangladesh and Thailand), all improvements were observed in countries with mid-range or high performance in this factor. Countries in the Americas and Asia and the Pacific account for 60 per cent of all advances, and no such improvements were observed in West Asia.

Some of these country-level advances may prove fragile. This is the case in Thailand, where struggles for control over the direction of political reforms are ongoing between the older, more traditional leadership and newer, more progressive parties (Simpson 2024). For example, events in 2025—especially plans to indict members of parliament from the now-dissolved Move Forward Party for sponsoring a bill in parliament to reform Thailand’s lèse-majesté law—cast doubts on the sustainability of recent gains (International IDEA 2025l).

Freedom of the Press and Freedom of Expression

The Freedom of the Press subfactor measures the extent to which the news media are diverse, honest, critical of the government and free from censorship (on the part of the government or self-imposed); it also measures independence of the media.

The Freedom of Expression subfactor refers to the right to openly discuss political issues and express political opinions outside the mass media and to considerations of the broader information environment.

Freedom of the Press was the factor that saw the broadest declines in 2024, impacting 43 countries at all levels of performance and in all regions. Similar downturns took place in Freedom of Expression, seen in 39 countries globally. Some of the steepest declines in both factors between 2019 and 2024 occurred in countries marked by closed and insecure contexts, including Afghanistan, Belarus, Burkina Faso and Myanmar. However, even relatively higher-performing countries such as Argentina, Austria, Georgia, Greece, Italy, Senegal, Taiwan and the United Kingdom saw mounting pressure on the exercise of one or both of these freedoms.

The office of the UN’s special rapporteur on the promotion and protection of the right to freedom of opinion and expression emphasized the threats to media and expression in a report published in June 2025. The document detailed attacks on independent media and called attention to campaigns, organized by vested political interests in a diverse array of contexts, to ‘undermine the credibility of independent media outlets and journalists who speak truth to power’ (Khan 2025: 7). The report also raised concerns about attacks on journalists, both in person and online, with women journalists facing particular risks (Khan 2025).

Recent developments in Georgia underscore the mounting pressure on media freedom and freedom of expression. In April 2025, the Georgian Parliament adopted several laws restricting civil society and media, including a so-called ‘foreign agents’ law that imposes expansive registration requirements and sanctions on independent organizations and media outlets. The April 2025 law is a harsher version of a law originally passed in 2024. The 2025 version tightens regulation on broadcasters, including new state-imposed coverage standards, and includes prohibitions on foreign funding, which journalists have criticized as mechanisms of state control and censorship (International IDEA 2025x).

Despite widespread declines in Rights-related indicators, there has also been some progress, most notably in Freedom of Expression, which shows the highest number of improvements among all factors in the Rights category. Low-performing Bangladesh and high-performing Spain illustrate how such advances can take place in highly divergent contexts.

In Bangladesh, one example of progress is the interim government’s annulment of the Cyber Security Act in November 2024, which had been widely criticized for suppressing free speech, press freedom and political dissent. The repeal of the act created space for a new law that omitted several of the most controversial provisions of the previous version (International IDEA 2024ah). In Spain, the government’s new Action Plan for Democracy includes measures meant to enhance both media independence and the right to information. Key initiatives include the drafting of an Open Administration Law to enhance the quality and accessibility of public information, the establishment of an independent whistleblower protection authority in public administration, measures for the disclosure of assets and interests by ministers and political parties, and legal safeguards to protect journalists’ sources. The plan also envisages the creation of a media register to improve transparency around media ownership and funding, to be maintained by an independent regulatory body (International IDEA 2024y).

Economic Equality

The Economic Equality index aggregates expert-coded measures of the extent to which people are excluded from political processes on the basis of economic factors, along with observational data about economic inequality.

Comparing 2024 to 2019, the number of countries experiencing declines (37) in Economic Equality was nearly triple the number registering advances (13) around the world (see Figure 2.6). Although the largest number of declining countries were in Africa, the regions were all fairly equally impacted, with the exception of West Asia, which saw only three such declines. The declines were largely concentrated in low or mid-range performers, with Singapore the only high performer to register a drop. Some of the steepest declines occurred in low-performing contexts (Afghanistan, Azerbaijan, Libya, Myanmar, Nicaragua and Qatar), but mid-range performers were also impacted (Canada, Iceland, Mauritius, Niger, Portugal, Romania and the USA).

The USA, which is among the 10 countries with the largest drops (its score fell from 0.69 in 2019 to 0.59 in 2024), has long struggled with high rates of inequality, illustrating how persistent economic disparities continue to challenge even long-established democracies. According to the latest data, the top 10 per cent of families in the USA hold 60 per cent of all wealth in the country, while the bottom 50 per cent hold just 6 per cent (Congressional Budget Office 2024). This disparity is reinforced by tax laws that apply lower rates to investment income—a major source of wealth for higher-income groups—than those applied to income earned from wages and salaries (Inequality.org 2025). In the first half of 2025, a series of policy decisions by the government raised concerns about deepening inequality. These decisions included the revocation of a prior executive order that had raised the minimum wage for federal contract workers and the elimination of collective bargaining rights for federal workers (Anderson 2025). The administration’s plans to cut Medicaid funding and change the rules that determine who qualifies for food subsidies also threaten to worsen inequality, particularly impacting lower-income groups (Luhby 2025).

Although the number of countries showing advances in Economic Equality was relatively small, gains were recorded across the full spectrum of performance. These included low-performing Bangladesh, Sudan and Timor-Leste; mid-range-performing Fiji, Jordan, Moldova, Saudi Arabia, Sierra Leone, Suriname, Togo and Zambia; and high-performing Malta and Slovenia.

Access to Justice

The Access to Justice factor denotes the extent to which the legal system is fair (i.e. citizens are not subject to arbitrary arrest or detention and have the right to be under the jurisdiction of and to seek redress from competent, independent and impartial tribunals without undue delay).

Comparing 2024 to 2019, performance in Access to Justice declined in 35 countries, which is more than twice the number of countries (15) that recorded advances. The majority of these declines occurred in mid-range-performing contexts, but two countries with much higher baseline performance also experienced notable deterioration in this area—France and South Korea. At the regional level, Africa and Asia and the Pacific accounted for the majority (57 per cent) of all the declines in Access to Justice.

Three of the five steepest drops worldwide occurred in low-performing Mauritania and Myanmar and in mid-range-performing Greece. Other mid-range-performing countries that experienced setbacks in this factor represent diverse contexts, including Ethiopia and Lebanon (both on the lower end of the mid-range spectrum).

In Greece, persistent concerns about impunity have hampered the pursuit of justice, especially for crimes related to media and journalists. Two high-profile cases in 2024 exemplify these challenges. The first involves the murder of a crime journalist, Giorgos Karaivaz, in 2021. Critics raised concerns about irregularities during the trial, including damaged evidence, and the eventual acquittal of the two men accused of the murder. The second case concerns the so-called Predatorgate scandal, in which state agencies were alleged to have used Predator spyware against multiple prominent individuals. Despite documented evidence of the National Intelligence Service’s role, the Supreme Court prosecutor cleared all state agencies of involvement (Human Rights Watch 2025). The decision was depicted by some observers as part of a pattern of impunity, especially in light of other longer-standing problems with the Predatorgate investigation. These include accusations against independent watchdog agencies that warned targets about the spyware and allegations that prosecutors were attempting to intentionally delay the investigations (Reporters without Borders 2023).

While declines in Access to Justice have been more prevalent, several countries across all levels of performance have also registered improvements. A particularly notable example is The Gambia, where steady improvement has been noted since 2017, when the country transitioned from low to mid-range performance. One of the most significant recent developments is the backing by the Economic Community of West African States of the establishment of a special tribunal for The Gambia to prosecute crimes committed under former President Yahya Jammeh’s rule (1994–2017). That period was marked by widespread repression, serious human rights violations, and control over the government and media. In 2022, the government accepted nearly all of the Gambian Truth, Reconciliation and Reparations Commission’s recommendations, and there is strong public support for the prosecution of former Jammeh officials (International IDEA n.d.b). The coming years will be critical in assessing the extent to which these commitments are implemented and whether they translate into lasting institutional reform and justice for victims.

2.4. Rule of Law

In the GSoD Indices, Rule of Law is an aggregate measure that includes assessments of the independence of the judiciary from government influence, the extent to which public administrators use their offices for personal gain, how predictable enforcement of the law is and the degree to which people are free from political violence.

Despite widespread challenges to the Rule of Law globally, a number of countries continue to set high standards in this area. These top performers demonstrate consistent strengths in judicial independence, low levels of corruption, predictable legal enforcement and strong protections against political violence. See Table 2.3 for the top 10 countries in 2024 in this category.

| 2024 rank | Country | 2023 rank | Change 2023–2024 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 |  | Denmark | 1 | 0 |

| 2 |  | Germany | 2 | 0 |

| 3 |  | Switzerland | 3 | 0 |

| 4 |  | Luxembourg | 5 | +1 |

| 5 |  | Australia | 11 | +6 |

| 6 |  | Estonia | 9 | +3 |

| 7 |  | Norway | 8 | +1 |

| 8 |  | Ireland | 7 | -1 |

| 9 |  | New Zealand | 6 | -3 |

| 10 |  | Finland | 4 | -6 |

Yet these positive examples stand in contrast to broader global trends. Out of all democratic performance categories, the highest number of aggregate-level declines occurred in the Rule of Law category. Comparing 2024 to 2019, 32 countries (19 per cent of those assessed) registered downturns in this category; most of these countries were either low- or mid-range-performing. European countries accounted for 38 per cent of the downturns, followed by countries in Africa, the Americas, Asia and the Pacific, and West Asia. The declines were evenly distributed across three factors—Judicial Independence, Personal Integrity and Security, and Predictable Enforcement—each representing between 28 and 29 per cent of the total. Absence of Corruption accounted for a smaller (16 per cent) portion of the total number of downturns. Nevertheless, corruption remains a salient political issue even when significant downturns are not present. In Serbia, for example, anger over entrenched political corruption fuelled months of massive nationwide protests instigated by the deadly collapse of the railway station in Novi Sad (Stojanovic 2024; International IDEA 2025b). Other cases are more mixed. India, for example, experienced a small decline in Judicial Independence (comparing its 2024 score to 2019). At the same time, however, it also saw the Supreme Court successfully order the first elections in Jammu and Kashmir in a decade, in October 2024, as well as issue a landmark ruling in November restricting the ability of state and local governments to conduct arbitrary demolitions of private property (International IDEA 2024ad, 2024ak).

See Figure 2.7 for an overview of how these trends changed between 2019 and 2024.

The rule of law has come under intensified pressure under the second Trump administration in the USA. Since Trump took office in January 2025, his administration has issued a series of executive orders attempting to overhaul key aspects of governance, including the day-to-day functioning of the federal civil service, the country’s migration and asylum systems, and the balance of power between federal and state-level governments (International IDEA n.d.c). In response, the federal district and circuit courts largely fulfilled their constitutional roles, staying or rejecting the policies and practices deemed arbitrary or capricious, compelling the executive to meet due diligence requirements, and upholding fundamental protections such as habeas corpus. In one notable instance, a court went so far as to threaten contempt proceedings against the government for non-compliance.8 Despite these interventions, the administration has at times disregarded or circumvented court rulings, prompting concerns about a potential constitutional crisis (Levy 2025). The degree to which the balance of powers is respected in the months and years to come will be a key determinant of whether Rule of Law indicators in the USA remain resilient or continue to deteriorate.

Advances in the Rule of Law were limited, impacting four countries in the Americas (Brazil, the Dominican Republic, Honduras and Suriname), three in Europe (Czechia, Latvia and Poland) and two each in Africa (Malawi and South Sudan) and Asia and the Pacific (Bangladesh and Fiji). These gains were largely concentrated in mid-range-performing countries. Bangladesh and South Sudan remain low-performing, and Czechia and Latvia are high-performing. No advances were recorded in West Asia.

Absence of Corruption

The Absence of Corruption factor denotes the extent to which the executive and the public administration more broadly do not abuse their office for personal gain. It is based on four indicators that measure corruption in the executive and public administration, and does not address courts and parliaments.

Gains in Absence of Corruption were recorded in 18 countries (10 per cent) across all regions (see Figure 2.7), marking the 15th consecutive year in which more countries improved than declined in this key area. While many of these gains were modest and should be interpreted with caution, they might signal growing attention to efforts to curb corruption.

Still, half of the countries showing progress remain in the low range of performance in this factor. The Americas accounted for one third of all advances in Absence of Corruption, with Guatemala standing out as an illustrative case of both progress and challenges. President Bernardo Arévalo, elected on an anti-corruption platform, assumed office in a context marked by entrenched corruption (International IDEA 2024w). Arévalo has undertaken initial steps towards reforms, including the removal of approximately 1,300 people from government positions on the basis of insufficient qualifications or a lack of merit-based recruitment. He has also led efforts to take complaints to the Public Prosecutor’s Office and has sought accountability from the attorney general—an official who has publicly opposed his presidency. At the same time, Arévalo faces significant resistance from actors who continue to challenge the legitimacy of his electoral victory and who have vested interests in maintaining the status quo (García 2024; Maldonado 2024).

Judicial Independence and Predictable Enforcement

The Judicial Independence factor denotes the extent to which the courts are not subject to undue influence from the other branches of government, especially the executive.

The Predictable Enforcement factor denotes the extent to which the executive and public officials enforce laws in a predictable manner.

Judicial Independence deteriorated (when comparing 2019 to 2024) across countries at all levels of democratic performance. Declines were evenly distributed between low- and mid-range-performing countries (10 countries each), and 2 high-performing countries—Norway and Spain—also experienced setbacks. The most severe declines were observed in contexts facing significant instability and violence, including Afghanistan, Chad, Myanmar, Palestine, as well as in El Salvador and Tunisia.

In other contexts as well, concerns emerged about judges’ ability to deliver impartial rulings. In Mexico, for example, a package of judicial reforms enacted in 2024 sparked intense debate. The reforms introduced the election by popular vote of all federal judges (including Supreme Court justices and Electoral Tribunal magistrates) and state judges, raising concerns about the possible impact on judicial independence. The reforms also created a Judicial Discipline Tribunal and an administrative organ of the judiciary to replace the Judiciary Council (formerly in charge of discipline and administration of the federal judiciary). The reforms reduced the experience and eligibility requirements for judgeships and amended judges’ length of tenure. While proponents of the reform argued that it was necessary to address judicial corruption and nepotism (International IDEA 2024aa), critics have warned of serious threats to judicial independence. The first judicial elections in Mexico took place on 1 June 2025, with low voter turnout and a significant share of spoiled ballots. The Organization of American States, of which Mexico is a member, has warned that these changes pose potentially far-reaching risks to the quality and independence of Mexico’s democratic institutions (Organization of American States 2024, 2025).

Additional mid-range countries experiencing declines in this factor include countries such as Argentina, Armenia, Bhutan, India, Indonesia, Nigeria and Slovenia.

There was also notable deterioration in Predictable Enforcement, with declines recorded in 21 countries—three times the number of advances (7). The distribution of declines was similar to that of Judicial Independence, with 9 low performers and 10 mid-range-performing countries. Two high-performing countries—the Netherlands and Spain—also registered declines in this factor. Regionally, African and European countries accounted for 62 per cent of the global declines in this factor, followed by Asia and the Pacific, the Americas and West Asia (see Figure 2.7).

Two mid-range-performing countries illustrate different dimensions of this decline. In Burkina Faso, the Transitional Legislative Assembly adopted a law granting amnesty for individuals convicted of participating in the failed coup attempt of September 2015. To qualify, applicants had to acknowledge their involvement in the coup attempt, demonstrate their commitment to national defence efforts, display good conduct during detention and agree to be deployed in military operations. While analysts suggest that the law aims to leverage the military and diplomatic expertise of certain figures in the fight against militant groups linked to the Islamic State group and al-Qaeda, critics warn that the move undermines accountability and the rule of law in the country, potentially entrenching impunity and weakening governance institutions (International IDEA 2024al).

In Ecuador, declines occurred in a very different context. Despite the outcome of a 2023 national referendum to end oil drilling in the Yasuní National Park, the government had not ceased operations as of mid-2024. A high court decision had given authorities a one-year period to stop oil exploration and comply with the results of the referendum. In August 2024, environmental activists and Indigenous leaders and groups asked the court to hold an urgent hearing on the matter (International IDEA 2024u).

Personal Integrity and Security

In the GSoD Indices, Personal Integrity and Security is a measure of the extent to which individuals’ bodily integrity is respected and people are free from state and non-state political violence. This factor includes measures of torture, political and extrajudicial disappearances and killings.

Comparing 2019 to 2024, more countries experienced declines than advances in Personal Integrity and Security. Over half (52 per cent) of these declines occurred in low-performing contexts, including countries such as Afghanistan, Belarus, Burkina Faso, Cambodia, El Salvador (see Box 2.3), Eswatini, Ethiopia, Guinea, Myanmar and Russia. People’s security also faced threats in higher-performing contexts like Portugal and Uruguay, the only high-performing countries that experienced drops in this factor.

Box 2.3. Personal integrity and security in El Salvador

Since March 2022, the people of El Salvador have been living under a state of exception instated at the request of President Nayib Bukele. Its purpose has been to combat gang violence, bring down the extremely high murder rate—a long-standing issue—and address persistent insecurity problems that are partly a legacy of the 1980–1992 civil war. The government has argued that the state of exception—and the ensuing suspension of certain rights—is justified and necessary to restore public security and enable citizens to go about their lives without fear.

Data from the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime show that in 2022, the year the state of exception began, El Salvador’s intentional homicide rate declined by more than half (UNODC n.d.). According to government records, by 2024 it had declined to 1.9 per 100,000 people, down from 107.6 per 100,000 in 2015 (UNODC n.d.; Cavalari, Manjarrés and Newton 2025). Although the exact statistics are disputed by some organizations and experts, authorities say homicide, extortion and gang violence have all declined considerably, and President Bukele is extremely popular (Vyas and Pérez 2023; Avelar 2025a). Despite a constitutional ban on consecutive re-election, Bukele was re-elected in 2024 with more than 80 per cent of the vote, reflecting the value placed on security by Salvadorans, the extremely disruptive effects of crime and lingering fatigue with previous leaders’ failure to contain it (International IDEA 2024b).

The ‘Bukele model’ has not been without devastating costs. El Salvador now has the highest rate of incarcerated people in the world (Watts 2015; Vyas and Pérez 2023; Stack 2024; Ventas 2024; Eisen 2025). Over 1 per cent of the population and about 5 per cent of men aged between 18 and 35 are imprisoned (Graham 2024; Méndez Dardón and Welch 2025). Over 85,000 have been incarcerated during the state of exception, including thousands of children (Human Rights Watch 2024; Méndez Dardón and Welch 2025). Mass hearings, arraignments and trials of up to 900 defendants are authorized under the state of exception. In addition to the issues related to mass incarceration, the country has experienced severe declines in Freedom of Expression, Freedom of the Press and Freedom of Association (International IDEA 2025y). Torture, enforced disappearances, deaths in custody and police abuse and intimidation are reportedly commonplace (Cristosal 2023; Stack 2024; OHCHR 2025).

In July 2025, Bukele’s allies in the Legislative Assembly even amended the country’s constitution to allow him to run for office indefinitely (Alemán 2025). Nevertheless, other countries in the region have praised and sought to emulate the Bukele model through the use of emergency powers, suspension of rights or the militarization of security forces (Freeman 2023; Phillips et al. 2025).

Threats to personal safety are a persistent challenge in the region, and popular demands that governments act to contain them are legitimate. But the success of the Bukele model against gang violence has come at the cost of the co-option of independent branches of government and institutions, human rights violations, and the severe deterioration of the rule of law and of civic space (International IDEA 2024g, 2025f, 2025y; Delgado 2025).

Three years into the state of exception, polls show that most Salvadorans still support Bukele’s security policies, although a large minority say that other methods should be explored (Kitroeff 2024; Valencia 2024; EFE 2025). Other surveys show that most Salvadorans fear negative consequences for criticizing their government (nearly half fear that the consequence could be incarceration) (Bergengruen 2024; Avelar 2025b). Salvadorans seem to have gained safety vis-à-vis criminals and gangs at the expense of safety from their own government.

Belarus saw some of the steepest declines in this factor compared with 2019. In April 2025, the UN and independent human rights experts raised concerns over a report that Belarusian authorities had sentenced at least 33 people to punitive psychiatric confinement since 2020, in retaliation for government criticism or participation in public protests. The trials were conducted in secret, and the resulting psychiatric confinement was typically of indefinite duration. Twenty-five people remained in confinement as of June 2025, with no publicly available information concerning their whereabouts. Political prisoners held in psychiatric institutions may be subject to forced medication or electric shocks. The opaque nature of the process means it is not possible to determine with certainty whether these transfers to closed medical facilities were made for political or medical reasons. Belarus has used psychiatric confinement as a punishment for political activism in the past, but the practice appears to have accelerated since the 2020 uprisings against President Alyaksandr Lukashenka (International IDEA 2025w).

Portugal has experienced different challenges, particularly in relation to police brutality. In October 2024, a police officer fatally shot 43-year-old Odair Moniz, originally from Cabo Verde, triggering large protests in Lisbon against police violence, organized by the rights organization Just Life (Vida Justa). In parallel, riots broke out around Lisbon, resulting in injuries, torched vehicles and 16 arrests. According to police reports, Moniz fled and resisted arrest on the night of the shooting; officers initially claimed that he was armed with a knife. The officer involved has since been charged with manslaughter, and both the General Inspectorate of Internal Administration and the police have opened investigations into the incident. The UN Committee on the Elimination of Racial Discrimination had previously expressed concern over the excessive use of force by Portuguese police, particularly against people of African descent (International IDEA 2024ae).