From Copenhagen to Doha: Democracy and the renewal of the social contract

This recognition comes at a critical moment. Democratic backsliding is accelerating, and progress on Sustainable Development Goal 16—peace, justice, and strong institutions—is off track. Gains in health, education, poverty reduction, gender equality, and employment remain uneven, threatening the 2030 Agenda. Foreign aid cuts risk compounding these setbacks.

A forthcoming report by International IDEA, under the SDG 16 Data Initiative, presents robust evidence on the democracy–social development nexus, drawing from its Global State of Democracy Indices and scholarly research. The report makes a clear case: democracy and social development must advance together to renew the social contract and fulfill the promise of Copenhagen, Doha, and the 2030 Agenda. Failure to deliver tangible progress risks eroding public trust in democracy itself.

Some of the key findings of the report are:

Democracies perform better than non-democracies on key social development indicators:

- Basic Welfare—covering health, education and nutrition—is on average 30 per cent higher in democracies.

- Gender, Economic and Social Group Equality are 40–47 per cent higher in democracies.

- Corruption levels are about 50 per cent lower in democracies.

The quality of democracy matters: In high-quality democracies, the differences are even starker: levels of Basic Welfare are about 66 per cent higher; levels of Gender Equality, Social Group Equality and Economic Equality are over twice as high; and levels of corruption are 90 per cent higher in non-democracies compared to high-quality democracies.

Table 1: Percentage difference between GSoD Indices scores: democracies (all performance levels) and non-democracies and by levels of democratic performance

|

% Difference between democracies (all performance levels) and non-democracies |

% Difference between high performing democracies and countries with low performance on all 4 GSoD pillars |

|

| Absence of Corruption |

51% |

90% |

| Social Group Equality |

47% |

89% |

| Economic Equality |

44% |

85% |

| Basic Welfare |

30% |

72% |

| Gender Equality |

40% |

66% |

Source: International IDEA 2019, International 2025

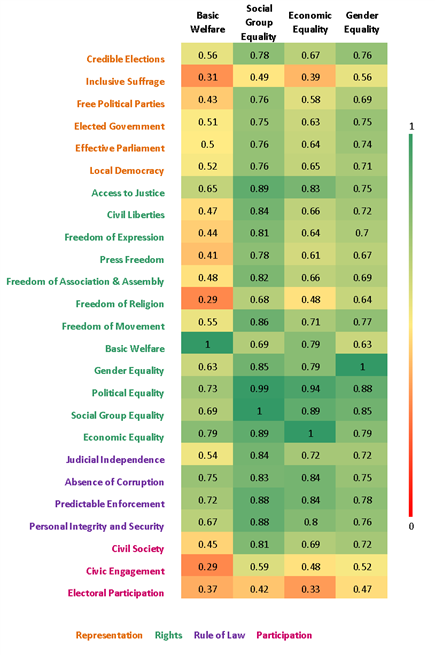

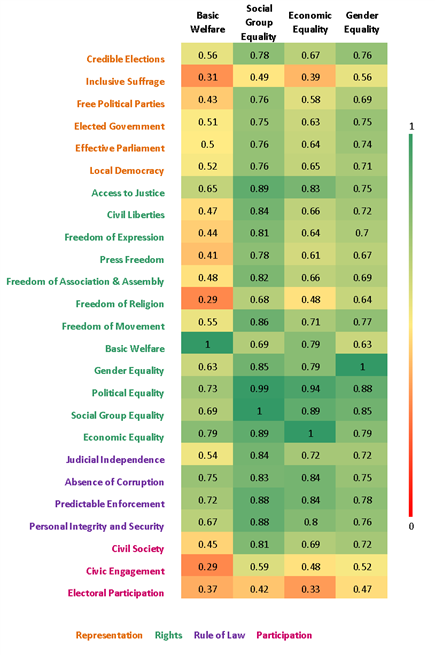

Rule of law is essential for social development and prosperity. An analysis of the correlations between the 29 GSoD measures and social development outcomes shows that governance and rule of law are most strongly linked to Basic Welfare and Economic Equality (Figure 1).

Democratic representation matters for how inclusively those gains are shared. Procedural dimensions of democracy—elections and effective parliaments and rights protection show stronger correlations with Gender and Social Group Equality, underscoring that governance may matter for basic welfare and fairness, but that democratic representation and rights are critical in determining how evenly and inclusively those prosperity gains are shared among social groups (Figure 1).

Figure 1: Correlations between GSoD Indices and selected measures of social development (0: low 1: high)

Source: Calculations based on the Global State of Democracy Indices 2025

Democratization drives progress in social development, while democratic decline reverses them. Drawing on scholarly studies, the report also shows that when societies democratize, they tend to experience stronger economic growth, see increased social spending, and improved social development outcomes, while autocratization or democratic decline typically reverses these gains, eroding prosperity and social development progress.

The evidence rejects the notion of an “authoritarian advantage”. Non-democratic regimes achieving substantial social development outcomes are empirical outliers. Out of 74 countries without democratic elections, only a handful achieve high levels of welfare or equality. Singapore is a rare outlier with low corruption, and Cuba and Serbia score relatively well on Gender Equality. But these are exceptions, not the rule. China, often cited as a model of authoritarian success, falls only in the mid range on welfare, equality and corruption indicators. None reach high levels of Economic or Social group Equality, with most autocracies struggle with inequality, weak service delivery and unreliable economic data.

Not all democracies deliver for its people. Despite strong correlations between specific dimensions of democracy and social development outcomes, the relationship is neither deterministic nor uniformly causal. Democratic governance does not inherently or consistently guarantee positive development results. Empirical evidence shows that many democratically elected governments struggle to deliver social development and prosperity for their citizens.

Perceived failure of democracies to deliver is linked to declining trust in democracy. While democracy is an enabler of social development and prosperity, when it fails to deliver, trust in democratic institutions can erode, undermining the social contract and fuelling support for authoritarian alternatives. Public opinion data across regions show that waning support for democracy often stems from perceptions of its failure to deliver social progress and shared prosperity.

Public opinion data show that:

- In Africa, 66 per cent of people prefer democracy, but only 37 per cent are satisfied with its performance.

- In Latin America and the Caribbean, support for democracy fell from 68 per cent in 2004 to 59 per cent in 2023, driven by corruption and economic hardship.

- In high income countries, satisfaction with democracy dropped from 49 per cent in 2017 to 35 per cent in 2025.

Pathways Linking Democracy and Development

The report identifies several pathways through which democracy enables social development:

Rule of Law and Corruption Control

Democracies tend to have stronger rule of law—62 per cent higher on average than non democracies (International IDEA 2025). This reduces corruption, ensures resources reach vulnerable groups and fosters equal access to justice. Studies show that lower corruption correlates with better health, education and poverty reduction outcomes. During the COVID 19 pandemic, democracies with lower corruption experienced fewer deaths.

Weaker rule of law undermines social development by enabling corruption that diverts public funds from health and education, inflates medical costs through counterfeit drugs, lowers school enrolment, deters investment due to legal uncertainty, and deepens inequality by allowing elites to capture benefits at the expense of marginalized groups.

Peace and Security

Violence and conflict undermine social development by destroying infrastructure, displacing communities, reducing school attendance, weakening health systems, and diverting public spending from education and health to security. Democracies are more likely to sustain peace, while participatory governance and women’s involvement in peace processes contribute to longer lasting recovery.

Representation and Participation

Elections and inclusive participation create accountability. Governments facing electoral competition are more likely to invest in health, education and infrastructure to win voter support. However, elections alone are insufficient—without strong rule of law and rights protections, electoral incentives may not translate into equitable service delivery.

Rights and Freedoms

Civil and political rights—freedom of expression, association and access to information—are essential for inclusive development. They empower citizens to demand better services, hold leaders accountable and ensure that gains are shared fairly across social groups. Where rights are suppressed, development tends to be less inclusive and inequality deepens.

Conclusion

Democracies are best placed to deliver inclusive and sustainable progress—but must show results to retain trust. The World Social Summit in Doha offers a vital opportunity to reaffirm democracy as central to social development and to renew the social contract.

Yet just as democracy needs to deliver, it also needs defending. Foreign aid cuts risk sidelining democracy and governance in favor of other pressing social development needs. That’s a mistake. Democracy is the enabler that ensures scarce public resources are used effectively, not siphoned off, and actually reach those in need.

In a world grappling with conflict, inequality, climate change, and democratic backsliding, democracy is not a luxury—it’s a lifeline. Crisis offers a chance to reimagine democracy—not just as a system of political rights, but as a foundation for social and economic justice.

Disclaimer: Opinions expressed in this commentary are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the institutional position of International IDEA, its Board of Advisers or its Council of Member States.

Acknowledgements: This article was written by Annika Silva-Leander, based on her forthcoming chapter 30 Years after the Copenhagen Declaration: Democracy, SDG 16 and Social Development: Nexus and Pathways which will be published as part of the SDG 16 Data Initiative Report 2025 on the nexus between SDG 16 and social development.