A Tale of Two Years: Findings from the Global Monitor of Covid-19's Impact on Democracy and Human Rights

Public health experts had been warning of the likelihood of a global pandemic for many years before Covid-19 became that long-feared pandemic in 2020. To the extent that governments had prepared for such a pandemic, most of the focus had been on the immediate dangers to life and health.

The secondary effects of pandemic responses on democracy and human rights did not become a major area of research until we were in the midst of the pandemic. Nonetheless, International IDEA quickly developed a data project to track the impact of Covid-19 responses on democracy and human rights. Two years after the pandemic started, we have published a new report: Taking Stock After Two Years of Covid-19 that takes a hard look at the data. One of the most devastating impacts we found—that pandemic restrictions most severely affected individuals and regimes with pre-existing vulnerabilities—was something decision-makers should have anticipated. Learning from our experiences, we must put forward more inclusive, responsive and accountable measures that protect public health while safeguarding our democracy and human rights.

Emergency legal responses

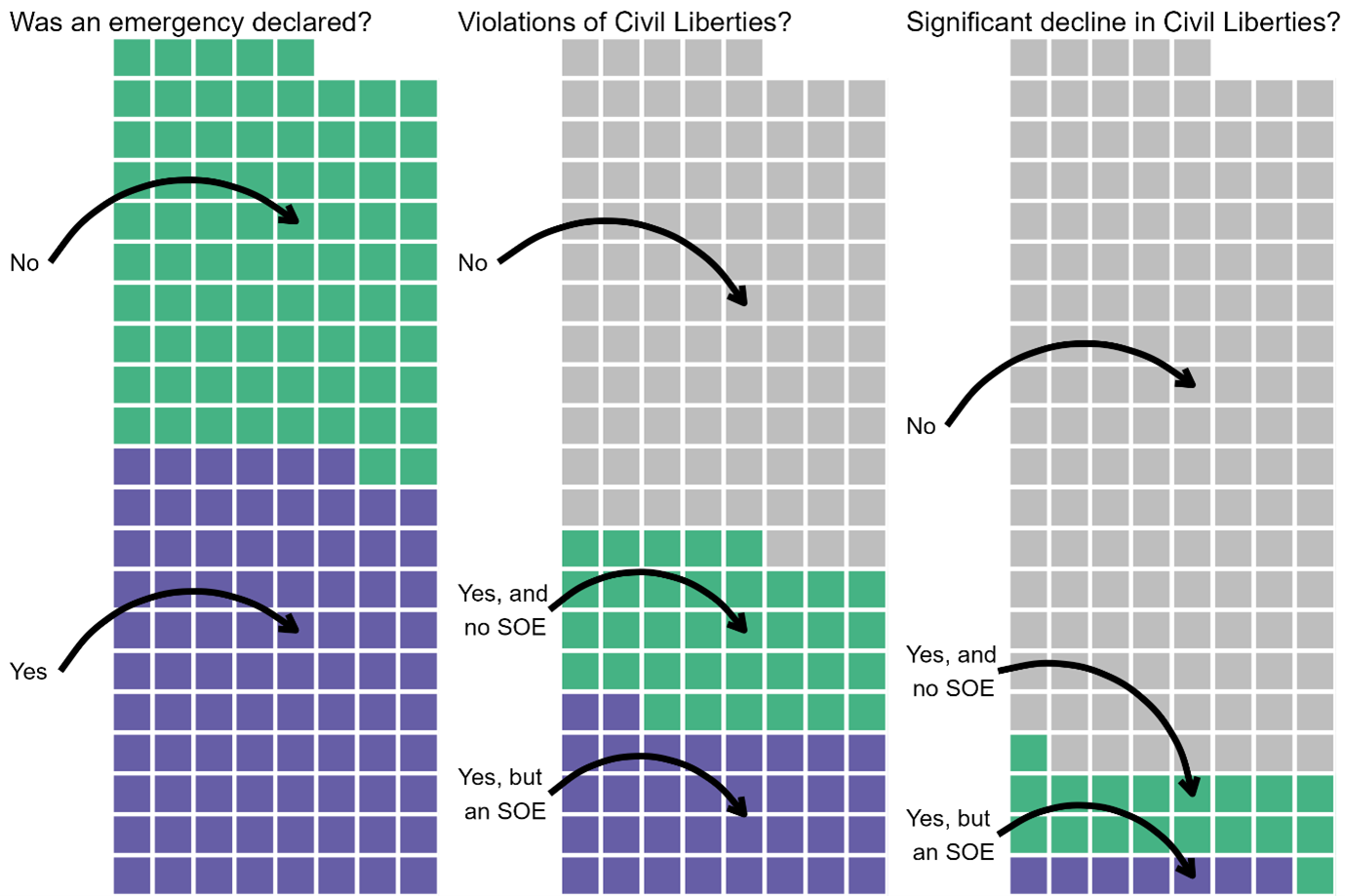

One might have expected that high-performing democracies would be the most likely to invoke emergency provisions to provide legal cover for extraordinary public health measures, but that was actually not the case. While 59 per cent of the 166 countries we cover invoked some form of state of legal exception during the pandemic, mid-range and weak democracies, along with hybrid regimes did so most often. High-performing democracies had the capacity to legislate their way through the crisis, while in authoritarian regimes emergency powers were not needed to take extreme steps. The invocation of states of emergency was not associated with more violations of Civil Liberties. Rather, our annual data show that the majority of countries that experienced a significant decline in this area had not invoked an emergency.

Restrictions on civil liberties

Certain civil liberties were restricted during the pandemic in the interest of protecting public health. With the exception of Turkey and Yemen, all of the countries we covered implemented restrictions affecting Freedom of Association and Assembly, including school and business closures, bans on public events, and limitations on the size of private gatherings. At least 89 per cent of countries introduced a lockdown at some point during the pandemic.

In much the same way, all countries we covered placed restrictions on Freedom of Movement, with at least 86 per cent of countries introducing border closures even though their effectiveness in preventing the spread of viruses is disputed. Lockdowns and other pandemic control responses were most devastating in developing countries, where more people rely on the informal economy for income. Going forward, restrictions that last beyond the point of community transmission should be questioned.

While Freedom of Association and Assembly was the most directly affected civil liberty, Freedom of Expression is of more concern going forward. This vital support of democracy had been under threat before the pandemic, and is under continuing stress due to three phenomena: a) a wave of repression of journalism, b) a flood of pandemic-related disinformation that continues to jeopardize public health measures, and c) an increase in laws against disinformation that are ripe for exploitation by anti-democratic governments.

Contact tracing apps

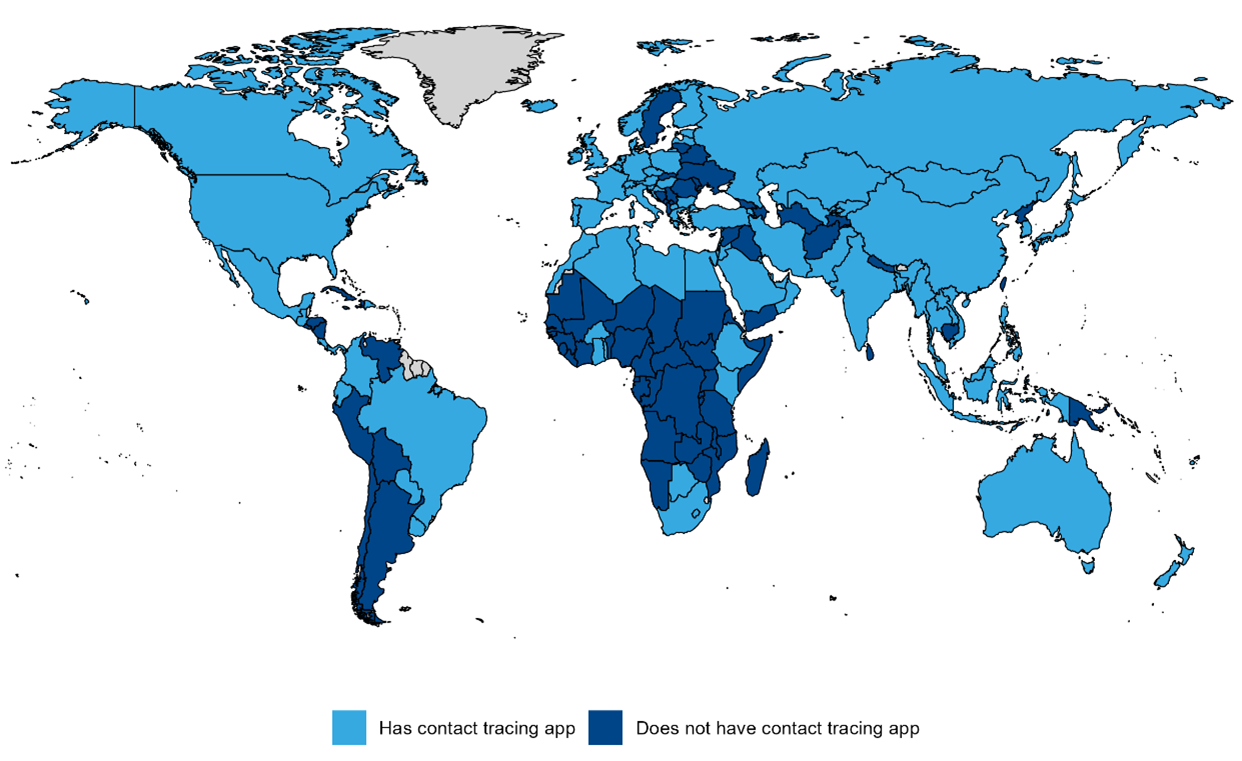

Data collected by a variety of organizations show that 51 per cent of the countries we covered deployed a contact tracing app (CTA), with the highest regional proportion in the Middle East (71 per cent) and the lowest in Africa (24 per cent). The first CTA however emerged in China in February 2020—before the potential for a global pandemic was known to much of the world.

The experiences of women and minorities

The pandemic has had disproportionate impacts on women and marginalized communities all over the world, including through an increase in violence, both in terms of domestic abuse and hate crimes, higher rates of unemployment, long term loss of educational opportunities and racial and ethnic minorities exposed to increased xenophobia and racism. Moving forward, it is vital that governments fully integrate the voices and needs of women and minority groups in the post-pandemic recovery processes.

Building back

Given humanity’s previous experience with pandemics and other emergencies, it is surprising that we were not better prepared for the impacts of Covid-19. One of the most devastating findings is one we could have expected: individuals and regimes with pre-existing vulnerabilities were the most severely impacted by the pandemic. Regimes that were already looking for ways to exert more control over their populations found pandemic-related justifications to do so. Governments everywhere struggled to find the proper balance between respecting individual rights and protecting public health.

We must think about how to better integrate disadvantaged groups at the front and center of recovery efforts and systematically into our institutions and mend the broken bonds of trust at all levels. The good news is that the mechanisms for dialogue and accountability that are at the heart of democracies are perfectly suited for the work that will go into rebuilding trust. Building back better is possible, but it means being responsive and accountable to everyone.