Protecting Elections in the Face of Online Malign Threats

In recent years, social media and online communication have become increasingly vital components of the news and information environment and have consequently amplified the impact and reach of disinformation. Social media is designed to boost content that generates engagement, in political contexts. This often results in polarizing and adversarial narratives being more likely to control the electoral environment. Research also shows that disinformation weakens democratic institutions and reduces citizens’ trust in the government and the media. Disinformation campaigns can affect public opinion, and the right to democratic participation, and jeopardize the perceptions of free and fair elections. In addition, authoritarian, populist, nativist, and illiberal leaders utilize these dynamics to maintain their online presence. These tendencies have become even more impactful as users are increasingly turning to online platforms for their main source of information.

Disclaimer: Opinions expressed in this commentary are those of the author and do not necessarily represent the institutional position of International IDEA, its Board of Advisers or its Council of Member States.

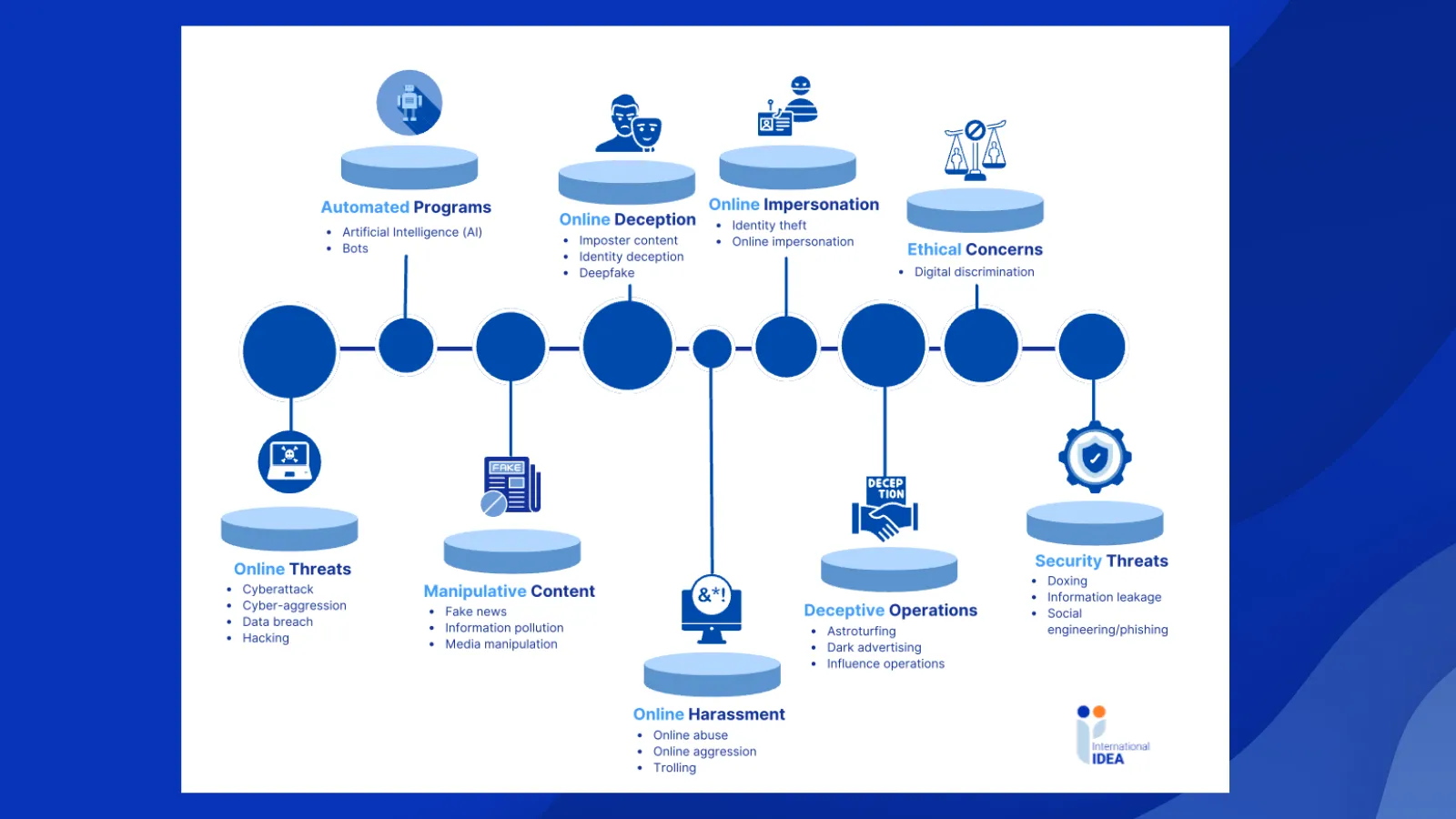

The information environment - recent cases of information disorder

From January 2022 to December 2023, at least 100 countries held national elections or referendums. Desk research conducted by International IDEA suggests that disinformation was an issue during the election cycle in at least twenty countries that held national elections and referendums during this period.[1]

In this period, malign actors engaged in the dissemination of election-related disinformation through various means. For example, in Slovakia, deepfake audio targeted a frontrunning political candidate just before election day; in Kenya, an electoral official was subject to online impersonation; and in Argentina and the United States, out-of-context videos were disseminated online to allege voter fraud and voter suppression. Moreover, female and minority political figures were subject to malicious rhetoric such as online misogyny and hate speech during national elections and referendums in this period.

Countermeasures to mitigate disinformation during elections

Recent elections and referendums in Argentina (2023), Australia (2022 & 2023), Canada (2019 & 2021), Germany (2021), and South Africa (2021) illustrate new approaches to combat the impact of disinformation on elections. Each electoral management body (EMB) put together its strategy to mitigate disinformation. Many of the strategies below are similar in approach despite large variations in country and electoral context.

Australia

In April 2022, the Australian Electoral Commission (AEC) launched a campaign to combat disinformation ahead of the May 2022 Federal election. The so-called “Stop and Consider” campaign, was designed for voters to take the time to consider if information is reliable, current, and safe. As part of this campaign, the AEC used YouTube and various social media channels to address electoral disinformation close to real-time. Moreover, the AEC launched a disinformation register featured on the AEC’s website. The register lists “prominent pieces” of disinformation relating to the election process. It also includes, for every case, information about when the AEC was informed of the specific case along with correct information and what action the AEC took in the matter.

The “Stop and Consider” campaign and disinformation register were reimplemented by the AEC for the 2023 Indigenous Voice to Parliament referendum, which saw several disinformation narratives attacking the impartiality and integrity of the AEC. The “Stop and Consider” campaign and disinformation register are both part of the AEC’s broader reputation management system (RMS).

Despite the challenges that online disinformation has posed for the AEC in recent elections and referendums, the electoral authority announced in December 2023 that survey results showed that the AEC was the most trusted public service in Australia among respondents in 2023. The AEC accredits its high level of trust and satisfaction among Australians to its prioritization of maintaining electoral integrity through measures such as the RMS.

Argentina

Ahead of the 2023 general elections, the National Electoral Chamber (CNE) collaborated with Meta to reduce election-related disinformation. As part of this effort, Meta implemented tools that aimed to make political advertising on their platforms more transparent. Additionally, the CNE collaborated with WhatsApp to create a chatbot containing accurate information regarding the electoral process. Users could ask the chatbot questions regarding polling station locations, valid voting documents, how to make electoral complaints, and how to justify vote abstention, to which the chatbot would send automated replies. This was a proactive measure undertaken by the CNE to counter election-related misinformation and to facilitate access for voters to reliable information regarding the electoral process.

Canada

In Canada, The Chief Electoral Officer, or Elections Canada, established a Social Media Monitoring Unit to track instances of false information relating to the election process or accounts claiming to be Elections Canada ahead of the 2019 federal election. The Unit noted several instances of false information being shared regarding the procedures for handling ballots and voter eligibility. Some of the cases were reported and subsequently removed, along with social media accounts. The Unit has also been working to follow up on the cases and accounts that remained a concern to the agency.

The social media monitoring function was reinstated before the 2021 general election. Elections Canada monitored election-related information on both major and alternative online platforms. Additionally, the agency monitored information on online platforms in additional languages, such as WeChat, Douyin, VK, and Naver. This comprehensive approach allows Elections Canada to quickly react to and debunk potential disinformation narratives regarding elections.

The aforementioned initiative aligns with the agencies, Electoral Integrity Office (EIO), set up in 2013, which has a mandate to monitor the information environment (nationally and internationally), prevent electoral malpractice, and build public trust.

Germany

Ahead of the 2021 Bundestag elections, the Federal Returning Officer, the electoral body responsible for the administration of elections in Germany, gathered examples of disinformation often occurring on social media platforms relating to the electoral process and conduct. Next to each false claim, the page features the correct information. The cases relate to topics such as the legitimacy of the Electoral Act, the Covid-19 vaccination and health requirements for voting, and the validity of Special Voting Arrangements such as postal voting.

Moreover, Agence France-Presse (AFP) partnered with Facebook prior to the 2021 Bundestag election to develop a WhatsApp chatbot aimed at combating disinformation. The chatbot allowed users to pose questions about information to the chatbot and send digital resources, such as photos or videos, in order to confirm whether these were legitimate. Members of the AFP editorial team would then assess the accuracy of the information.

South Africa

Ahead of the 2021 Municipal Elections in South Africa, the Electoral Commission and Media Monitoring Africa (MMA) entered a partnership with social media platforms to combat disinformation during the electoral process. The cooperation initiative consisted of two interlinked key software tools to identify and report instances of disinformation. The first tool, known as PADRE, is software to specifically identify and eliminate mis- and disinformation contained in advertisements on all media platforms. The second part is a system that lets the Commission after a case has been raised as potentially containing false information, notify the online platform in question. Every participating social media platform recruited teams to prioritize these errands from the Commission during the election period.

The IEC informed voters on how to report online disinformation via the Real411, the online platform developed in cooperation with the MMA to counter disinformation, through its YouTube and Facebook accounts during the 2021 municipal elections. Additionally, the IEC used its X (formerly Twitter) account to debunk election-related disinformation, such as one instance in which individuals were falsely impersonating electoral officials through mobile communications.

Elections in 2024 and beyond

Global trends suggest that disinformation during elections is likely to continue throughout 2024 and beyond. 2024 will be a historic year for elections, with approximately 70 countries scheduled to hold elections, including some of the world’s most populous democracies such as Brazil, India, Indonesia, and the United States. Further, 2024 will be the first time that several of these large democracies hold general elections since the use of generative AI tools such as ChatGPT has become widespread. Experts have highlighted that there is significant concern that election-related mis- and disinformation are being spread more extensively than in previous years through the use of AI technologies, such as deepfakes. According to a recent report from the World Economic Forum election disruption caused by AI was regarded as the biggest global risk in 2024. Therefore, experiences and lessons learned from countries to combat the spread of disinformation concerning electoral processes are important for other countries who are seeking to strengthen their disinformation mitigation strategies.

Source: International IDEA, ‘Protective Infrastructure in Election Information Environment: Global Overview’, January 2024

In January 2024, International IDEA launched a new dashboard that focuses on the protective infrastructure as part of a broader initiative to protect electoral processes in the information environment. This ‘protective infrastructure’ dashboard provides country information on the electoral system, legal framework, institutional mandate, cooperation, and countermeasures that aim to reduce the impact of disinformation in elections. The dashboard currently includes information on 10 countries (Argentina, Australia, Canada, Chile, France, Germany, Mexico, Netherlands, South Africa, and Sweden) and will be updated with additional country briefs throughout 2024 and beyond.

Electoral Commissions will never be able to control the information environment during elections, but countermeasures designed to monitor, fact-check, inform, and educate voters will certainly help to strengthen their capacity to protect elections.

[1] Costa Rica, Colombia, France, The Philippines, Serbia, Slovenia, Uruguay, Kenya, Chile, Israel, Nepal, Australia, Fiji, Nigeria, Paraguay, Thailand, Guatemala, Argentina, the United States and Brazil.