Political, legal and organizational lessons from elections in the time of a pandemic – Republic of Poland

The second round of voting in Poland’s presidential election on 12 July will bring to a conclusion a remarkable electoral process, which saw a nearly all-time high turnout of voters during the first round on 28 June, despite the COVID-19 pandemic. Both the incumbent President Andrzej Duda of the Law and Justice Party (PiS) and his challenger Rafał Trzaskowski of the Civic Platform (PO) hope for a high turnout of their supporters, as polls put them neck and neck. Every vote will matter, and voters overseas who had registered in high numbers for the first round (over 374,000 out of some 30,2 million eligible voters) set a new record for the second round, expecting to make a difference. The Ministry of Foreign Affairs reported that its consulates sent out around 480,000 postal voting packets to voters abroad by 5 July, responding to earlier criticisms that some voters did not receive their ballots in time for the first round.

It was postal voting in the country that attracted much attention from election practitioners in early April, when Poland’s government announced its intention to hold the election only by mail. While PiS opponents urged the government to introduce a state of emergency and postpone the election until the autumn, the ruling party sought to counter the COVID-19 threat by switching to voting by post. In the following weeks, a government ministry proceeded with preparations for the election scheduled for 10 May, without waiting for the respective legislation to be adopted by the parliament, and bypassing the National Election Commission (NEC).

The government’s determination to proceed with the May postal election brought Poland to the brink of a political and institutional crisis. In the face of growing criticism at home and abroad, presidential candidates threatening boycott, and local governments refusing to cooperate, a compromise was brokered by dissenting voices from the ruling parliamentary majority. The election scheduled for 10 May did not take place and the NEC handed a legal “lifeline” to the government, enabling the scheduling of a new election date of 28 June.

New legislation was adopted on 2 June, which provided for continuity of the electoral process. Registered candidates were able to stand for the 28 June election and preparations for polling were led by the NEC. Election commissions at the regional and polling station levels were formed, although their composition was altered, reflecting the lower rates of applications. Campaign financing rules were adjusted to cover both the first campaign and the newly scheduled date.

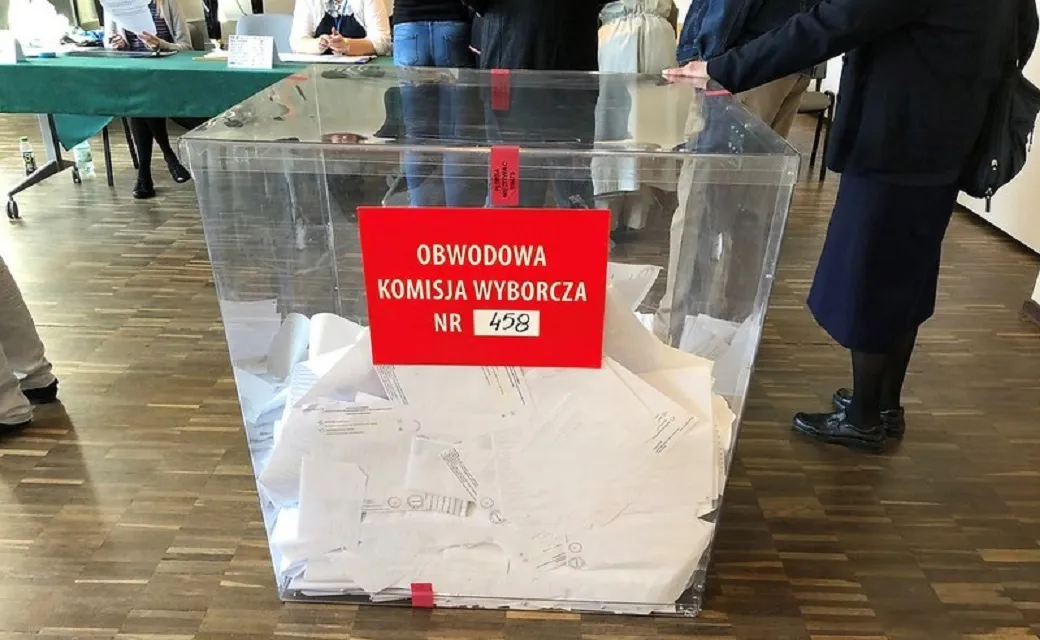

In contrast to the first postal voting bill, the new law gave voters a choice to apply for a postal ballot or cast their vote in polling stations. Voting was held over one day and voting hours were the same as in previous elections: from 07:00 to 21:00. What did make voting different on 28 June was a range of health protection measures implemented at polling stations. These included disposable gloves for Precinct Election Commission (PEC) members, hand sanitizer at the entrance to each polling station, face masks and vizors for PEC members, social distancing, not covering tables with absorbent material, regular airing of polling stations and disinfection of surfaces touched by voters.

Turnout on 28 June was 64.5 per cent, the highest in the first round of presidential elections since 1995. It showed not only the importance of this election in Poland but also that voters were not put off by the COVID-19 epidemic. As to postal voting, which attracted so much attention, this option was chosen by around 185,000 voters in Poland in the first round (compared to 42,800 in the first round of the 2015 presidential election). Concerns that counting high numbers of postal ballots in the country and abroad may delay voting results have not materialized.

The second round on 12 July will be closely watched by public health professionals. New COVID-19 infections rose somewhat after the first round but did not appear to lead to a significant spike. Poland’s Minister of Health optimistically quipped that going to vote on Sunday will be “safer than going shopping”. Election practitioners in other countries will also be keen to see whether the health precautions undertaken were sufficient to ensure a safe election day. The second round will conclude a fascinating story of an electoral process during the coronavirus epidemic. For a detailed and in-depth analysis of Poland’s case, please see International IDEA and Electoral Management Network case study: Political manoeuvres and legal conundrums amid the COVID-19 pandemic: the 2020 presidential election in Poland.

Disclaimer: Views expressed in this commentary are those of the author. This commentary is independent of specific national or political interests. Views expressed do not necessarily represent the institutional position of International IDEA, its Board of Advisers or its Council of Member States.