Line goes down: Or, how not to read a democracy report

Disclaimer: Opinions expressed in this commentary are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the institutional position of International IDEA, its Board of Advisers or its Council of Member States.

If you’re reading this blog post, you’re most likely a person who is used to looking at trend lines. Trend lines are everywhere, tracking things like stock prices, sea-surface temperatures, crime rates, and electrical generating capacity. Trend lines are good for almost any simple measure that varies over time. In most cases, when ‘line goes up’ or ‘line goes down’, the import of that trend is clearly good or bad. We are often tempted to apply the same simple analysis to movements in trend lines that illustrate changes in measures of democratic performance. As much as only understanding the health of an industrial conglomerate through its share price would be a mistake, using the value of a democracy index as the sole measure of a country’s democracy is an error.

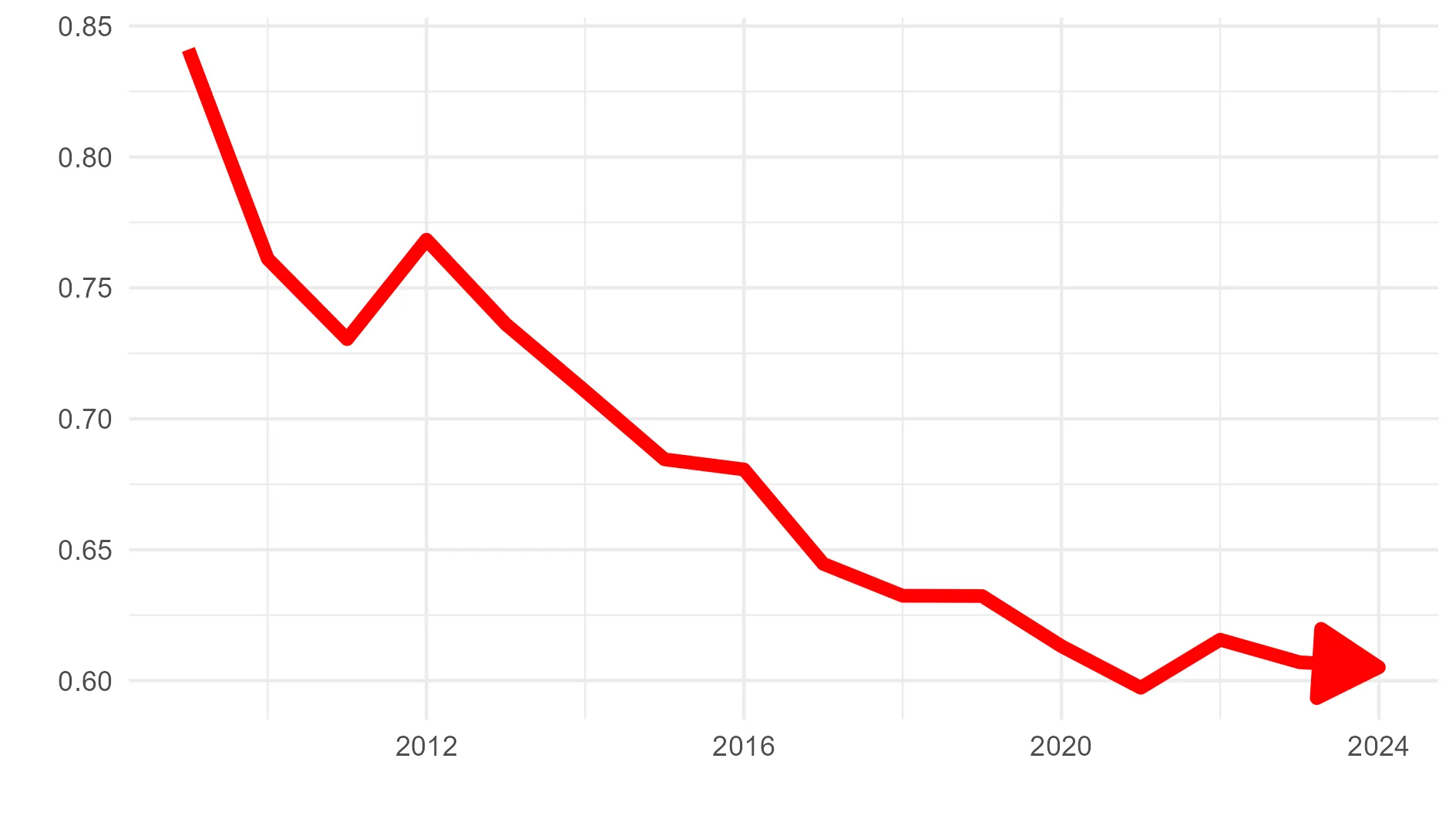

Even so, we are all busy people, and reducing the complexity of the world into summary statistics is an important contribution. In our most recent report on The Global State of Democracy, we found that 54 per cent of the countries we cover (173) suffered a decline in at least one factor of democratic performance. That statistic glosses over a lot of complexity, but it is a simple fact that helps anyone understand the general trend of democracy in the world. For each country we cover, we have also added line graphs illustrating the trend over time (see Annex B). These provide a reasonable ‘snapshot’ of the direction of travel in each country.

However, over-reliance on these lines is an instance of the common tendency to objectify the thing that is represented by the trend line. The dynamic here can be illustrated with reference to an object that moves in a two-dimensional space, such as a ship. We can observe the track of a ship at sea, noting when ‘it’ (or ‘she’ if you are nautically inclined) turned in one direction or another. We speak as if the ship made these turns itself. But in so doing, we pay no direct attention to the commands of the captain to her crew, the extent to which the ship’s owners or agents gave instructions, the functioning of the engines or steering gear, or anything other than that the ship turned.

Now, a ship is most certainly an object, so perhaps we’ve done no violence to the truth there. But a democracy is most certainly not an object. A democracy does not turn up or down even though its trend line may do that. Rather, the data represented in a trend line in a report on democracy represent a measure of something specific and limited in scope. The change in that measure is the product of the actions and decisions of many people. Most importantly, the elite focus of the concepts being measured means that the line will sometimes go up or down in response to changes in the party in power (if these parties differ in their attitude toward democracy). What that line does not capture is the deeper level of commitment to, or practice of, democracy among the multitude of people that are participants in that country’s democracy.

The upshot of this is that we should read democracy reports with close attention to what is being measured and reported. A trend line illustrating change in a concept like Absence of Corruption or Credible Elections is a reflection of elite behaviour that may change quickly. Those measures do not reflect the sum and total experience of corruption or elections for the mass public, or their attitudes toward democracy or elections.

Why does this matter? A narrow focus on the movement of the lines can lead to false understandings of the context of democracy in a particular country. For example, the lines for Poland have been going up since the 2023 legislative election and the formation of a new government under the Civic Coalition. If we only look at that, we would not see that the former governing coalition retained a plurality of the popular vote, and that a candidate supporting that coalition won the Presidential election in 2025. Clearly, there is a large share of the Polish population that supported the previous government’s actions that were classified by many as ‘democratic backsliding’, and it is possible that that path may one day be taken again. So, even if the lines for Poland go quickly up now, and may go down again in the future, the larger picture of democracy in Poland is different. The level of support for the former autocratizing government has not dramatically dropped off, and its supporters have not significantly changed their views. The same could be said of the recent ups and downs in the lines for Brazil and the United States of America.

As an author of one of the major reports on democracy in the world, I definitely encourage everyone to read them (ours, for example). I even encourage people to see if the lines go up or down. But we learn a rather limited amount from those trends. We should not objectify a democracy; instead, we need to look deeper and try to see the diverse people and complicated actions that inform the data that line summarizes. Incidentally, International IDEA provides information of this kind in some of our other work in the Democracy Tracker. We live in complicated and ‘interesting’ times and there may be a lot happening below the line.