One year into Covid-19: Paving the way to change in electoral policy and practice. Will it endure?

Over a year has passed since, on 11 March 2020, the World Health Organization (WHO) declared Covid-19 a pandemic and warned of sustained risks of further global spread. One year on, we have seen how the pandemic has forced a major re-evaluation of long-established electoral policies and practices, transforming the way in which, over the last decades, electoral management bodies (EMBs) have conventionally administered and delivered election after election.

Disclaimer: Views expressed in this commentary are those of the author. This commentary is independent of specific national or political interests. Views expressed do not necessarily represent the institutional position of International IDEA, its Board of Advisers or its Council of Member States.

As the pandemic will eventually abate, the following questions arise:

- Will the Covid-19 crisis prove the force of change in electoral management policy and practice that, already for some time, has been expected?

- If so, what opportunities have emerged? and

- How much of this expansion will last, which changes prompted by Covid-19 will endure in the management of future elections?

Exposing pre-existing limits and vulnerabilities

The major unpreparedness as to how an election could be safely administered in a pandemic that was brought to the fore by Covid-19 was no novelty, as several vulnerabilities were already showing the strain in the management of elections before the shock of this crisis across the globe. The pandemic laid bare pre-existing systemic limitations and inadequacies of established policies and practices, reaffirming, with heightened force, their inability to meet pressing needs imposed by a constantly evolving world. Covid-19 did not bring all these vulnerabilities—it upended them, giving them new vigour, making them acutely clear and throwing them back on table.

This was particularly evident in countries, states and territories where important needs and inadequacies in the management of elections had been systematically considered—but acquiescently overlooked—for a long time. As the pandemic hit, it made it impossible for them to neglect or ignore these needs and inadequacies any longer: at once, Covid-19 made not only feasible—but necessary and unavoidable—advancements in the management of elections that previously seemed legally, politically, financially or operationally unachievable or that, while still being important, were considered negligible, unimplementable, as too expensive or legally impossible.

Sweeping the way for long overdue change

Recognising that, amid its multiple challenges and limitations, the pandemic has also paved the way to substantial change in electoral management policies and practice, it is then reasonable to wonder, once Covid-19 will eventually abate, what of these advancements can be expected to dissipate, and what instead will endure?

History suggests that, in the aftermath of global crises, the change they induced rarely disappears in its entirety. Some of the changes imposed by Covid-19 to the management of elections are seemingly temporary: hopefully, the wave of postponed elections1 that characterised the first months of the pandemic will not occur again; and hopefully, when voting in future elections, the use of safety measures, disinfectants and personal protective equipment will no longer be required, or even less be forgotten, as new pandemics or similar health emergencies may still arise.

Some other changes in electoral management policies and practice will instead not only endure but will likely continue to drive and shape how future elections are administered by EMBs, contested by political parties, taken part in by voters and scrutinised by observers, beyond the course of the pandemic, in two ways.

First, the last year saw accelerations of electoral management trends that were already under way before the sudden spread of the pandemic. The pressure and resulting motivation to experiment and introduce new electoral practices and approaches—whether making voting safer, more voter-friendly, accessible and convenient by scaling-up special voting arrangements (SVAs)2; or resorting to digital technology3 or social media platforms to overcome the restrictions on traditional in-person election campaigning; or devising innovative, remote election observation techniques—pushed the timelines forward for reforms that, at some point, were likely to occur for other reasons.

Second, the rapid adaptation of the management of elections to the Covid-19 crisis, exposed fault lines of established electoral policies and practices which, developed and refined over decades of democratic evolution, had been designed and adopted to preserve election integrity in a different world order; they were meant to protect against different, and largely foreseeable, risks through solid—but overly prescriptive and rigid—frameworks, systems, norms, regulations, procedures and operations that they were often not allowing EMBs to respond to unpredictability with the requisite swiftness, flexibility and agility of action.

The pandemic reinforced the realisation and emphasised the need for a periodic and systematic review of the rules, norms, methods and procedures that govern the organization and administration of elections, highlighting the value of resilience, agility and adaptability in the fulfilment of the mandated functions by the EMBs.

Challenges looming beyond Covid-19

Aside from shaking the foundations of electoral policies and practices that had been consolidated over several decades, and forcing them to adapt and change, the pandemic has also shed light on new, forthcoming challenges that, looking ahead, EMBs can—and should—expect in the management of future elections. Such challenges include:

- New emergencies will arise: beyond the Covid-19 crisis lurk many others: natural disasters or extreme weather events; malicious foreign interference in sovereign democratic elections; terrorist threats; the deliberate exploitation of future crises by authoritarian leaders to undermine democratic institutions and processes; and widespread political disillusion possibly leading to voter apathy. While EMBs cannot eliminate emergencies, they can enhance their own ability to pre-empt or resolve them, or at least mitigate their impact, when they materialise, with effective emergency and risk management plans in place; EMBs can be better prepared for unexpected disruptions that may affect the smooth and regular administration of elections.

- How to sustain advances and innovations over the next electoral cycles: the pandemic introduced a new, more adaptive, electoral management model, which was not existing only a year ago. Having to respond to the challenges imposed by the pandemic, EMBs were urged to aim at higher performing standards: to protect the wellbeing of all those participating in the elections, not only they had to ensure stronger public safety, but also greater professionalism, transparency, accountability, service mindedness, and administrative, procedural and operational efficiency. Some of the legal, regulatory and procedural advancements and innovations cannot be retracked once the pandemic abates and the world normalises. Consequently, the regulation, refinement and use of the advances made in electoral management may prove more difficult to be sustained in the long-term, than their swift introduction as a rapid, one-off reaction to the Covid-19 crisis.

- Further attempts will be made to erode public trust in the management of future electoral process: populism, the raise of new nationalism, exacerbated political polarisation, foreign interference in sovereign elections and the global spread of disinformation are all factors likely to continue further eroding public and stakeholder trust in independent, transparent and accountable electoral management in future electoral cycles. EMBs should reasonably expect that this, in turn, will most likely heighten public expectations and stakeholder demands for error free, transparent, modern and efficient administration of future elections.

- Incessant social change, economic crises and demographic growth will continue to hinder electoral inclusion, participation and representation: not all countries, states and territories have brought their existing voting methods up to enfranchise large numbers of voters who are, and will continue to be, increasingly on the move across the globe. Predictably, steady and large-scale populations growth will continue to intensify migration flows and voter mobility, within and across countries and regions, reinforcing the need for broader electoral inclusion of some vulnerable groups still notably and largely disenfranchised.

Limits of traditional polling station voting

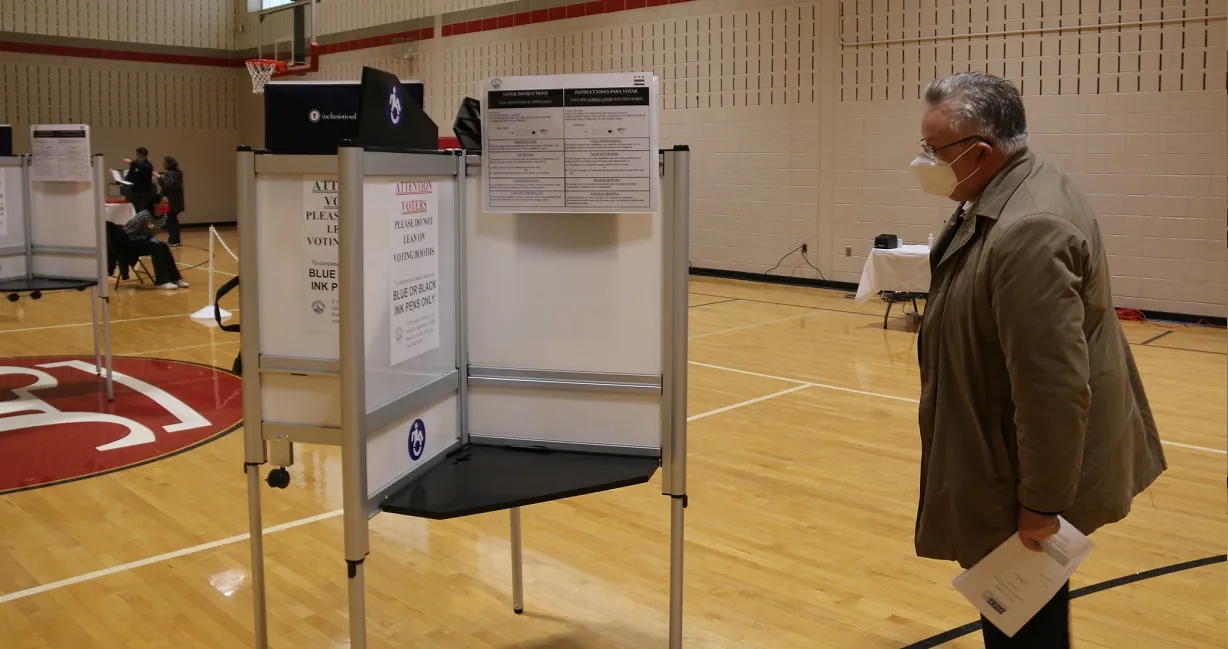

Currently, most countries, states and territories across the world conduct their elections solely through the employment of ‘traditional’ voting methods that are rigidly compelling their respective electorates to vote in one way, and one way only: to cast their ballot, on election day, those eligible to vote must appear in-person at the assigned polling station in the constituency of registration.

The dataset recently complied by International IDEA reveals that, globally, one third of countries, states and territories are not offering any SVAs to their in-country voters: Europe, with only 14 per cent of its countries using solely traditional polling station voting methods, is the continent with the lowest number of such cases, followed by Oceania (22 per cent) and Asia (23 per cent); in Africa, the proportion is significantly higher, at 44 per cent; the highest proportion, with 52 per cent, is found in the Americas and when examining 20 countries4 of Latin America, it reaches as much as 75 per cent.

Commonly, traditional voting revolves around three requirements:

Requirements of traditional voting

|

These three requirements provide a strong, largely unquestioned integrity to this traditional voting method which nowadays remains the ‘gold standard’ in voting practices and is conventionally adopted as the primary method to vote in democratic elections across the globe. From an electoral management perspective, traditional voting has proved optimal since the strictly regulated, controlled and secured environment of the polling stations is generally construed as limiting occurrences of irregularities—such as vote buying, coercion of voters, or family voting, tampering with ballot boxes, etc.—which may characterise an election. This method is considered as guaranteeing strong levels of security, secrecy, transparency, and procedural integrity to all steps of the voting process.

Aside from its procedural integrity, the method of voting in person at a polling station also protects, and strengthens, the individual and collective political engagement that routinely culminates with one’s participation in an election. Today, traditional voting continues to hold a strong societal value for many, which is symbolised in the recurrence of a social ritual5 through which voters, on election day, with the power of their ballot, converge at the polling stations to determine who should—or should no longer—represent them in the resulting institutions of governance.

However, despite the strong societal value and procedural integrity of traditional voting, Covid-19 has rapidly proven this method as anachronistic and inadequate, corroborating the notion that:

- Traditional voting, on its own, is no longer capable to guarantee the enfranchisement of voters who are, in today’s world, increasingly on the move; and

- To meet evolving and pressing needs of present-time elections, electoral policies and practices require urgent review, adjustment and more meaningful applicability to new, evolving realities normally arising through the passage of time.

One of the main limitations of traditional voting is that, typically, the physical, spatial or temporal requirements of this method continue to disfranchise those voters that, for any reason, cannot attend their assigned polling station on election day. While several countries, states and territories offer SVAs to their electorates, for the most they currently remain reserved only to a privileged few and select categories, such as government employees, military personnel or voters residing abroad.

Rethinking electoral participation

Before Covid-19 swept across the globe, established democracies took pride in traditional voting methods and electoral management practices constantly developed and refined over decades, or even over the course of centuries. The pandemic—bringing renewed global attention to long established, but not as consistently and broadly employed, SVAs as safer alternatives to traditional voting—has given renewed impetus6 to the opportunity of majorly rethinking electoral participation, as it has been traditionally known, interpreted and endeavoured.

The pressure that Covid-19 imposed on the management of elections, in turn, has accelerated several trends that were already underway and—chief among them—that of moving voting away from the polling stations.

Through this challenging year, with so many elections unfolding under the pandemic, SVAs allowed voters to vote with greater levels of personal safety, while also providing easier, more accessible, convenient and practical channels to cast their ballot, by either:

Voting in person |

By still attending the polling stations—but casting their ballots during an earlier and longer period than on a single day, with more polling booths, fewer people, fewer possibilities of getting infected and more convenient methods; or |

Voting remotely |

Through an ‘absentee’ vote, by casting one’s vote away from polling stations—from a safer and more easily accessible location, also during an earlier period. |

Flushing longstanding voting practices out of their prolonged rigidity and stillness, the pandemic has laid bare systemic limits and inadequacies in meeting broader enfranchisement needs of today’s increasing mobile and globalised world.

Through the course of history, as democratic systems, processes and institutions gradually became more and more inclusive, participatory and representative, and the electoral franchise kept expanding to keep up with the passage of time, voting methods had to constantly adjust and evolve, to respond to specific demands of new social and political orders, major economic and demographic changes, and other crises and realities coming to the fore. However, after several centuries of progressing voting practices, present-time elections remain, by and large, outpaced, too statically and strictly grounded at the polling stations, where voters—to cast their ballot—are still rigorously compelled to appear in person, on election day.

Elections held in the times of Covid-19 have revealed a disjuncture between the constant, dynamic evolution of electoral enfranchisement needs and the current stillness and passive unresponsiveness of traditional voting methods. While the passage of time has been urging for some time traditional voting methods to evolve and enfranchise those still disenfranchised, such methods have been lagging instead.

A hard choice: the convenience of voting or the integrity of the elections?

Exposing systemic limits and vulnerabilities of established electoral policies and practices, and of traditional voting methods was the easy part. The hard part is how to navigate the inherent tension between making voting more convenient for voters—the inclusion, participation and representation dividends—and the genuine and likely risks to electoral integrity that come the further voting moves away from the controlled, regulated and secure environment of the polling station7. Hence, when contemplating the introduction of SVAs, decision-makers and EMBs should be cognisant that these methods are neither quick solutions nor one-size-fits-all answers, but that instead their effective introduction, incessant refinement and sustained use in the long-term should be founded on, and guided by, important considerations.

When introducing new SVAs, or reforming existing ones, the following questions may be asked:

Special Voting Arrangements Checklist |

|---|

|

While it must also be acknowledged that not all countries, states and territories possess the required infrastructure, the means and resources, the capability, or even the desire, to introduce, manage and maintain SVAs—yet—it is through political will, through appropriate and sustainable solutions drawn from own experience—but also from that of others—that electoral frameworks can be gradually strengthened and improved, for future elections not only to become safer, but also more voter-friendly, convenient, accessible and inclusive.

In addition to forcing the world to take stock of its multiple challenges, risks and restrictions, Covid–19 has also reinforced the understanding that, to further strengthen and safeguard our democracies, greater, more consistent and sustained efforts are needed—now more than ever—to make future elections the truly inclusive, participatory, representative and trusted processes they are meant to be.

Ultimately, the pandemic confirmed that the strategy solely moving towards bringing voters to the ballot box, alone, is no longer capable to meet multiple pressing and, for the most, largely unanswered needs of present–time elections. To be more effectively and realistically aligned with today’s—and tomorrow’s—demands, such strategy needs to be complemented by efforts that are also moving in the other direction, that of bringing the ballot box to voters.

In so doing, voters should be allowed to choose whether to cast a ballot by traditional voting means, or instead opt for an array of alternative methods they deem safer, more meaningful, or simply easier, most accessible, practical or convenient for them.

Endnotes:

1. Data gathered by International IDEA indicates that from February 2020 to March 2021, at least 76 countries, states and territories postponed national and subnational elections due to Covid-19.

2. SVAs include absentee and early voting methods, such as postal voting, inter-constituency voting, mobile voting, drive-thru/curb side voting, e-voting, internet voting, etc.—typically used in-country or overseas.

3. Such as augmented realty (AR).

4. Namely Argentina, Bolivia, Brazil, Chile, Colombia, Costa Rica, Cuba, Dominican Republic, Ecuador, El Salvador, Guatemala. Haiti, Honduras, Mexico, Nicaragua, Panama, Paraguay, Peru, Uruguay and Venezuela.

5. Orr, G. (2015): ‘Ritual and Rhythm in Electoral Systems: A Comparative Legal Account’; Ashgate/Routledge.

6. Under the pandemic, SVAs became instrumental in elections held in numerous countries, such as Germany-Bavaria, Republic of Korea and New Zealand.

7. Pearce Laanela, T. (2021): ‘Special Voting Arrangements: Between the Convenience of Voting and the Integrity of Elections’.

References:

-

Aman, A., ‘Elections in a Pandemic: Lessons from Asia’, The Diplomat, 5 August 2020, <https://thediplomat.com/2020/08/elections-in-a-pandemic-lessons-from-asia>

-

Asplund, E., ‘International IDEA: Elections and Covid-19: How special voting arrangements were expanded in 2020’, 25 February 2021, <https://www.idea.int/news-media/news/elections-and-covid-19-how-special-voting-arrangements-were-expanded-2020>

-

Birch, S. et al., ‘How to hold elections safely and democratically during the COVID-19 pandemic’, 2020, London; British Academy, <https://www.thebritishacademy.ac.uk/publications/covid-19-how-to-hold-elections-safely-democratically-during-pandemic/>

-

Orr, G., ‘Ritual and Rhythm in Electoral Systems: A Comparative Legal Account’; Ashgate/Routledge, 2015, <https://www.routledge.com/Ritual-and-Rhythm-in-Electoral-Systems-A-Comparative-Legal-Account/Orr/p/book/9781138087040>

-

Pearce-Laanela, T, ‘Special Voting Arrangements: Between the Convenience of Voting and the Integrity of Elections’, 2020, <https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=mzOmcrUCnx4>