Insuring elections: A paradigm for protecting electoral integrity

Most of us are familiar with the concept of insuring our valuable assets, be it our house, car, or health. Professionals and businesses can also buy insurance to protect themselves against liability or loss. However, despite being a critical asset of democracies, a comprehensive insurance policy for protecting the integrity of elections does not exist.

Without arguing its feasibility, the insurance paradigm provides a refreshing lens for thinking about protecting elections. So, if it were to exist, what could be the benchmarks for offering and buying such a policy?

Most of us decide on purchasing an insurance policy by weighting three factors: the value of the asset we want to protect, the likelihood of its damage or loss, and the quality and affordability of insurance policies. Insurers’ reasoning is more methodological as they need to optimize the ratio of expenses and revenues. They define ‘rating variables’ to approximate the risk by evaluating the characteristics of an asset and the policy owner. For example, when companies ensure homes, they consider their value, location, safety features, etc. Rating variables for car insurance often include the year and model of a vehicle, as well as the driver’s age, gender, and incident history.

This gives us enough methodological insights to discuss three key rating variables for the imaginary electoral integrity insurance policy.

Rating variable 1: Value of election integrity

An election integrity is defined as “any election that is based on the democratic principles of universal suffrage and political equality as reflected in international standards and agreements, and is professional, impartial, and transparent in its preparation and administration throughout the electoral cycle”. Elections are essential for individuals to fulfil their fundamental human rights by electing their political representatives periodically. For democratic societies, alternation of power through elections is critical for functioning democratic institutions. Therefore, elections are a public good of the highest order and worthy of protection.

But it is hard to put a price tag on electoral integrity. The direct cost of an election is often presented as an expense per voter, and can range from three to 200 USD per voter. For example, the cost of 2022 federal general elections in Canada was 500.8M CAD (385M USD) or approximately 18.30 CAD for each registered elector. In Indonesia, the total budget for the 2019 elections was 25,59 Trillion Rp (over 1.6B USD). Indirect costs can be even higher. For example, the USA presidential and congressional candidates spent over 14B USD in 2020. Some countries have picked the hefty bill for failed elections. For example, the inability to account for 1400 ballots during the 2013 West Australian Senate poll resulted in new regional elections at the estimated cost of 20M AUD. The cost of repeated 2017 elections in Kenya, annulled by the Supreme Court, was 100M USD. When elections fail in conflict-prone societies, they can cause large-scale violence and destruction of infrastructure that may devastate the economy. The unplanned rerun of presidential elections in Malawi, necessitated by unaccepted results from the first round and the violence that broke out in protest of the outcome of the first round, incurred the cost of over 26M EUR. Also, election-related violence resulting from disputed 2007 elections caused the loss of 3.7B USD to the Kenyan economy.

Rating variable 2: Likelihood of damage or loss

In mature western democracies, the conduct of elections and the integrity of electoral processes have traditionally been taken for granted. However, this perception is fast changing among electoral administrators and governments. There are many examples where electoral integrity is undermined by domestic actors who resort to undemocratic means to pursue electoral advantages or derail the implementation of election results. The USA elections in 2020 is a recent and well-known case of the incumbent president trying to undermine electoral integrity to stay in power. Some Latin American countries historically experience challenges with organized crime groups that interfere in elections. In Afghanistan, the Taliban have targeted elections for years. Many European countries have encountered malicious foreign interference in electoral processes orchestrated to undermine their democratic institutions. The conduct of elections can also be disrupted due to natural disasters such as floods or wildfires (forthcoming International IDEA 2022). Recently, the Covid-19 pandemic triggered an unprecedented stream of postponement of elections worldwide. The conduct and integrity of elections can also be disrupted due to profound political crises or wars.

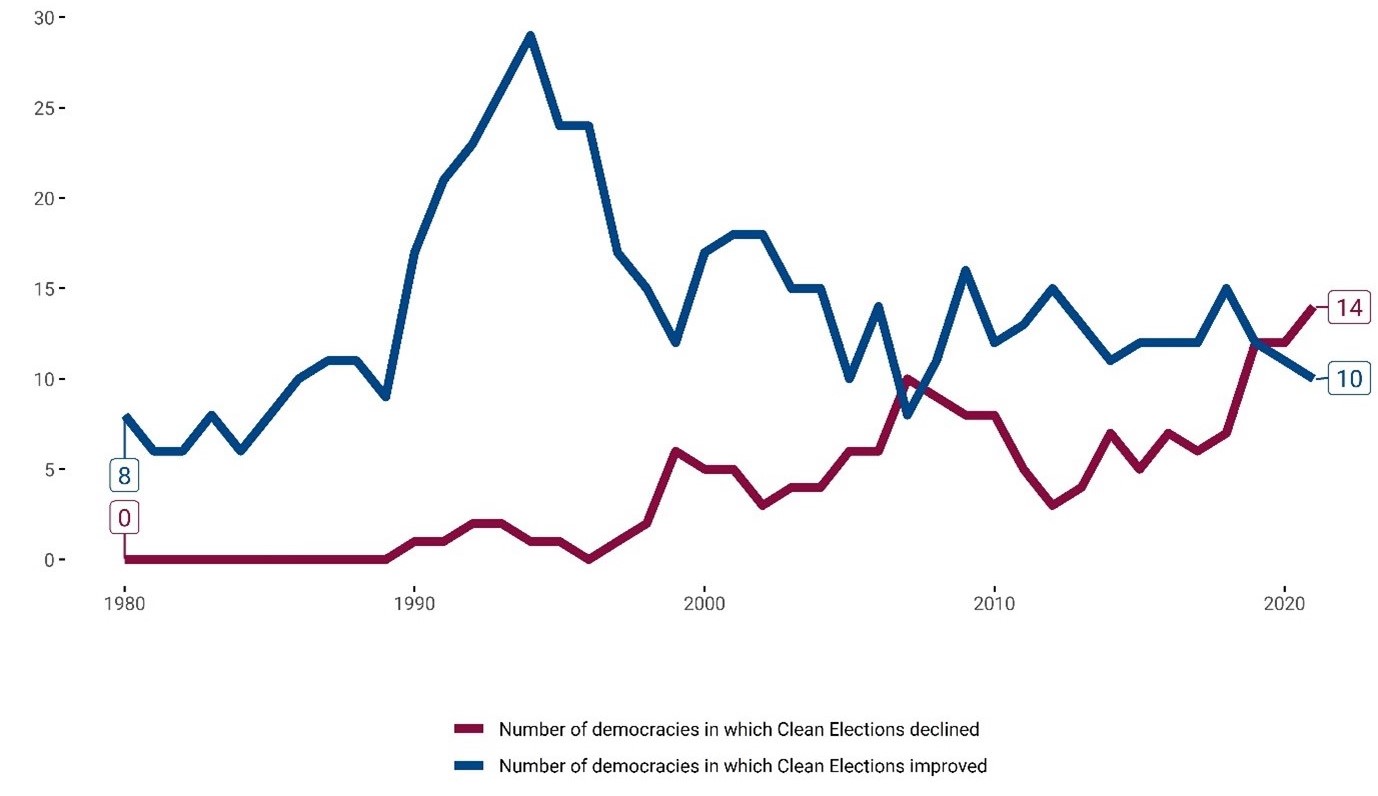

Every democracy - present and past - has some track record on electoral integrity whose analysis could offer an insurance benchmark. While the premiums for transitional democracies would be rather high, the recent elections in some well-established democracies would see a price hike. International IDEA’s Global State of Democracy Indices show that 14 democracies have experienced declines in Clean Elections since 2016: Bolivia, Botswana, Brazil, Bulgaria, El Salvador, Ghana, Guatemala, Guyana, Hungary, India, Lebanon, Mauritius, Namibia and Poland. During this time period, seven other countries lost their democratic status due to severe declines (Benin, Comoros, Côte d’Ivoire, Mali, Myanmar, Serbia and Turkey). In 2021, for the third time in the last 20 years, the number of democracies with declines in the quality of their electoral processes exceeded those with advances; see the figure below.

Source: International IDEA, The Global State of Democracy Indices v.6.1 , 2022,

Rating variable 3: Existing electoral integrity securities

Systemic securities of electoral processes are entrenched in the legal and institutional framework for conducting elections, namely the electoral law and the mandate of the electoral management body. The quality of these securities would be essential to assess when pricing the electoral integrity policy. For example, does the legal framework for the conduct of elections establish a levelled playing field for all electoral actors, including ruling and opposition political parties? Can citizens participate as voters and candidates regardless of gender, ethnic or religious background, age, or disabilities? Also, the legal framework should entrench transparency of the electoral process that caters to the engagement of domestic and international election observation groups. Elections in many old democracies are governed by legal acts and traditions that are centuries old. For those reasons, legal and institutional arrangements in many mature democracies would score low.

In terms of the institutional framework, the functional independence of electoral management bodies enables impartial decision-making. Experiences show that competent and trusted electoral management bodies stand a greater chance of navigating electoral processes through complex environments and protecting the integrity of its outcomes. However, strong mandate, impartiality, technical skills and funding for implementing electoral activities, although necessary, no longer offer sufficient warrant for protecting electoral integrity. To effectively respond to emerging electoral challenges, electoral management bodies need to adopt new working patterns that enhance their ability to prevent risks from materializing, demonstrate resilience in the face of stresses and shocks, or effectively recover from crises that can cause loss of continuity. In this respect, the electoral administration's mandate and track record in standardizing the use of, and learning through, the state of the art management practices, such as risk management, resilience-building and crisis management, may be an essential assessment benchmark.

Сonclusion

In the insurance metaphor, national governments and electoral management bodies are policyholders on behalf of citizens. Proxies to insurance policies are international electoral and democracy assistance programmes availed by development organizations.

Governments committed to electoral integrity and excellent electoral management bodies versed in managing risks and dealing with stresses and crises can do much to protect the integrity of their elections. Where domestic resources and experiences are scarce, while social polarization and environmental risks are heightened, international electoral assistance can be a helping hand. Therefore, numerous governments and intergovernmental organizations stand ready to provide advisory, technical and financial support for enhancing electoral integrity. Their revenue is a global public good, namely - democratic stability and prosperity worldwide. Certainly, one can’t argue the lack of affordability.

However, the review of the effectiveness of international electoral assistance yields a mixed bag of results. Critical challenges are in: that we often fail to apply lessons learned, that electoral assistance actors (national stakeholders, donors and implementers) may have different priorities, and that we sometimes fail to recognize and react to emerging challenges in time. A shared understanding of the value of electoral integrity for citizens, governments and the international community, recognition that the risk of damage or losing electoral integrity is real and increasing, and that systematic ways to protect elections exist will help achieve alignment in pursuit of common goals.

Opinions expressed in this commentary are those of the author/s and do not necessarily represent the institutional position of International IDEA, its Board of Advisers or its Council of Member States.