The Colombian run-off elections: two winners and a sweet defeat

Disclaimer: Views expressed in this commentary are those of the staff member. This commentary is independent of specific national or political interests. Views expressed do not necessarily represent the institutional position of International IDEA, its Board of Advisers or its Council of Member States.

Este articulo se encuentra disponible en Castellano.

The second round of the Colombian presidential elections, a duel between the extremes of the political spectrum, was held on Sunday, 17 June 2018, with two clear winners—Iván Duque and Álvaro Uribe—and a sweet defeat for Gustavo Petro.

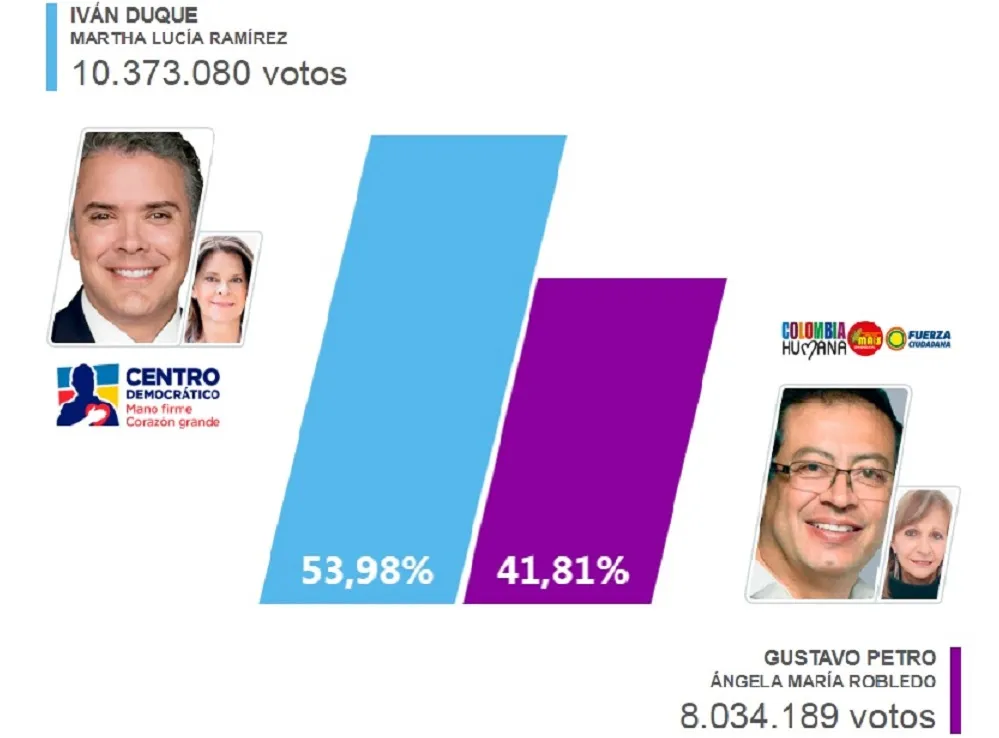

This time the polls were not mistaken, and the right-wing Duque, who had already won the first round, won the run-off over the leftist Petro for a significant difference of 12 per cent: 53.98 per cent versus 41.81 per cent, a triumph that in the regional scope reinforces the predominance that the center-right political forces have been obtaining in South America.

The defeat of Petro could well be characterized as “sweet” since for the first time the Colombian left made it to a second-round presidential election, received more than 40 per cent of the votes, and won the support not only of the left but also of the center-left, which in the first round preferred Sergio Fajardo. With this result, the candidate of Colombia Humana, from his seat in the Senate, is very well positioned to be not only the leader of the opposition but also a key figure in the 2022 elections.

The challenges facing Duque

The priorities of the Duque administration—the new president will be inaugurated on 7 August 2018—include four main challenges and one strategic objective: succeed in unifying a very polarized country.

The first challenge is to guarantee the successful implementation of the peace accords. “The peace that we long for calls out for corrections,” said Duque, who has promised that while he is not going to “tear up” the accords, he is going to introduce important changes which, if carried out, will generate major tensions, especially with the former guerrilla force.

The second challenge is to ensure political governability. While Duque has a solid group in the legislature, it remains to be seen how the political relationship with his mentor Uribe will unfold; from his seat in the Senate, he will seek to influence the government’s actions. The composition of the cabinet will be a first test for Duque to make it clear that he is in charge.

The third challenge is related to his reformist proposal (orange economy), which seeks to modernize the Colombian economy, making it more competitive, pro-business, with lower taxes and a smaller informal sector. This proposal will face serious challenges due to the complex legacy that President Santos is leaving in relation to the economy and in social policy, especially the marked inequality.

The fourth challenge entails the complex relationship that his administration will maintain with the authoritarian regime of Nicolás Maduro—who Duque has characterized as “illegitimate”. The relationship is closely tied to the evolution of Venezuela’s political crisis, and the wait to see how the critical socio-economic situation and the increasing flow of persons who are leaving Venezuela ends up impacting Colombia.

Summarizing: the first presidential elections in the post-conflict period after the peace accords were signed with the FARC were the most peaceful in the country’s history; they confirmed that Colombia continues to be a center-right country; the great clientelist regional political systems were defeated, they saw historically high levels of participation (52 per cent); and for the first time a woman, Marta Lucía Ramírez, will serve as vice president of Colombia.

However, this has been a process which, as Ariel Avila notes, is characterized by a paradox: the peaceful unfolding of the election process is a direct consequence of the peace policy pursued by President Santos, yet the winner (and therein lies the paradox) turned out to be the political force most tenaciously opposed to that peace policy.

This article was originally published in Spanish in Perfil. The English translation was undertaken by International IDEA.