Democracy in the Western Balkans: A Long and Winding “European Path”

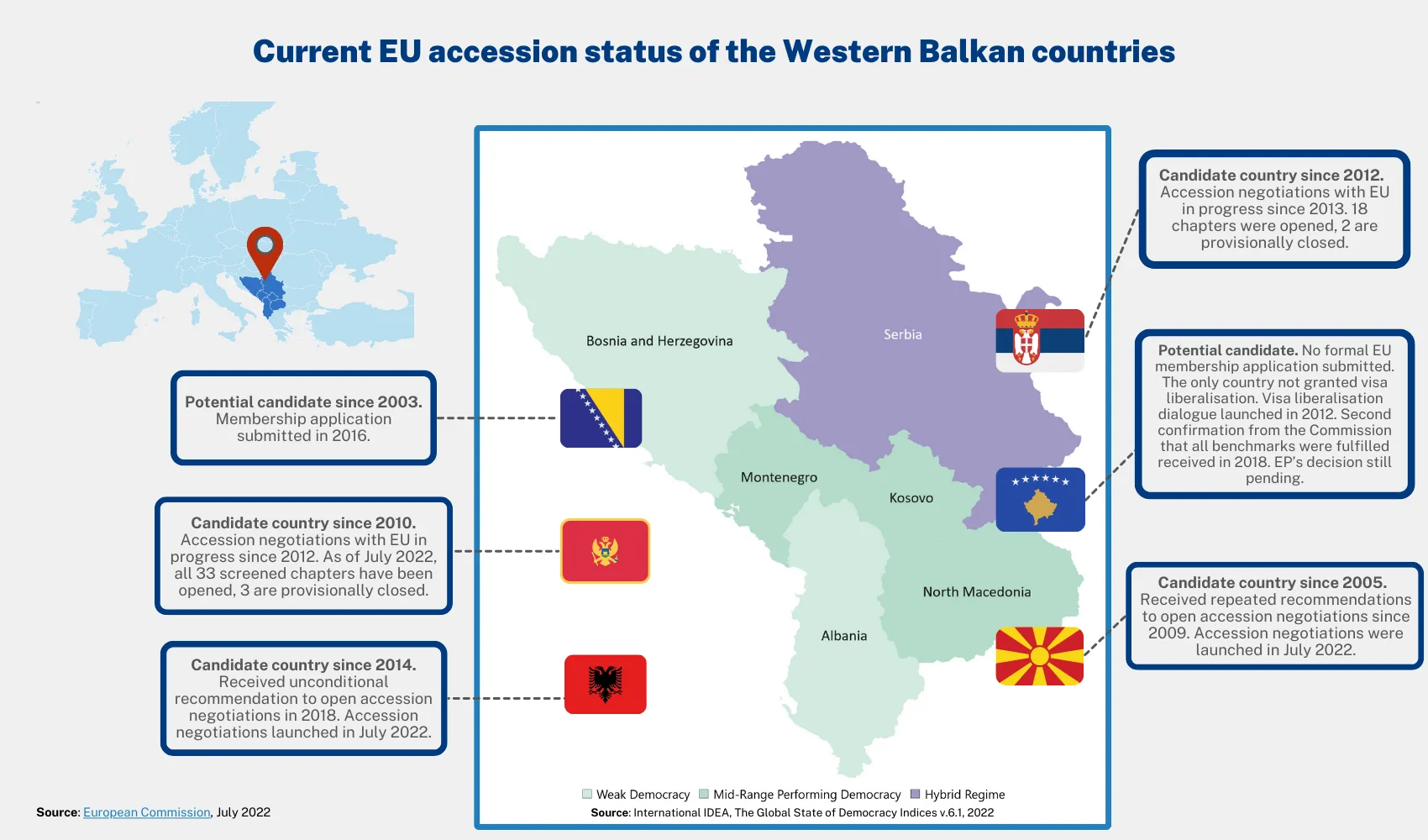

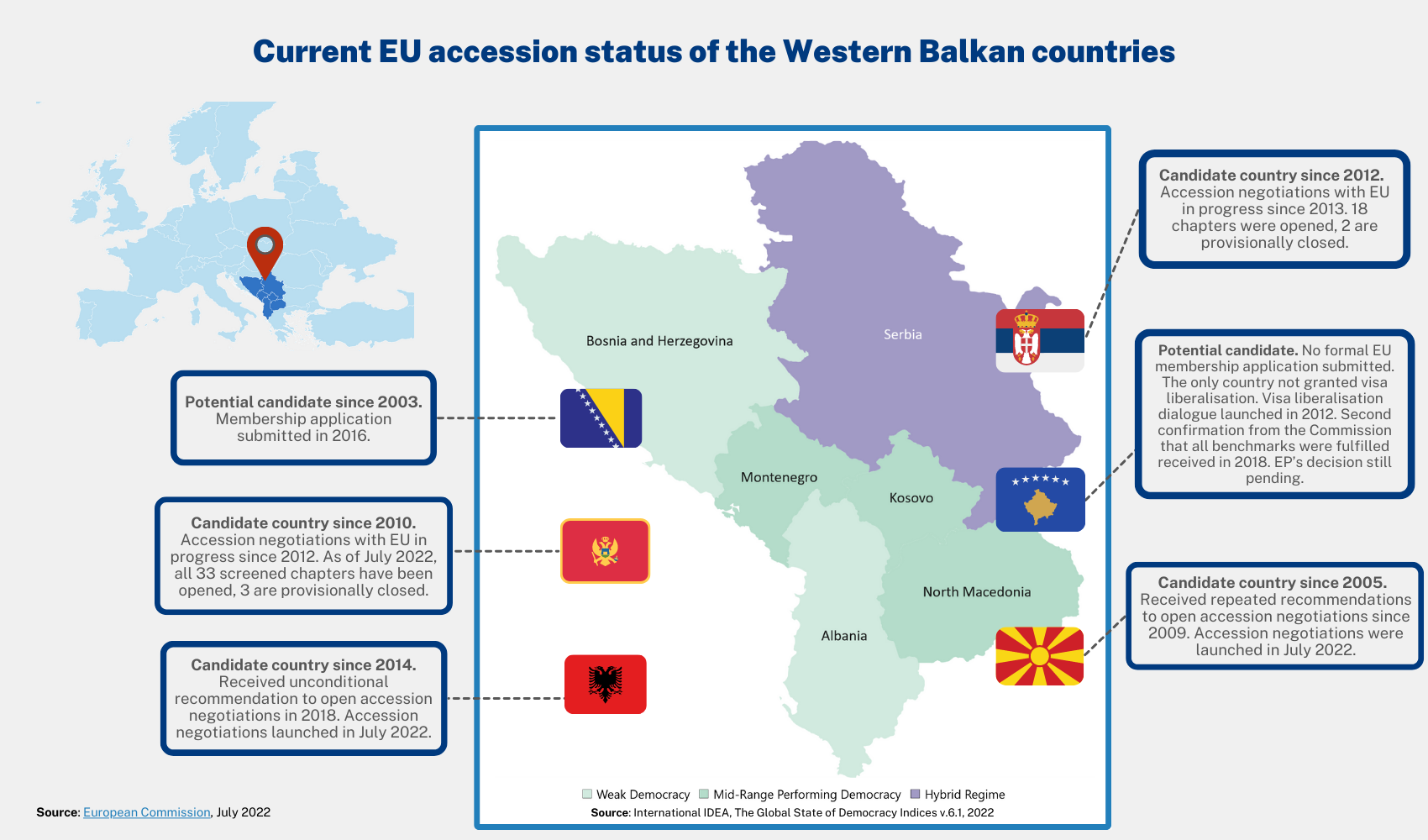

After the longest period of stasis in its history, the European Union is expanding. Last month, Ukraine and Moldova were swiftly granted candidate status. Bulgaria, an EU member state, voted to lift its veto on North Macedonia’s and Albania’s membership bids, and North Macedonia in turn committed to new legal measures recognizing Bulgarian minority rights, clearing the path for the start of negotiations.

Stalled integration of the Western Balkans and the latest EU Summit aftermath

The accelerated pace with which Ukraine and Moldova gained candidate status left the Western Balkans, long stuck in the EU waiting room, feeling sidelined and frustrated. Albanian Prime Minister Edi Rama criticized EU leaders, referring to the stalled accession process as a “scary show of impotence.” The discontent is nothing new, but Rama’s undiplomatic language speaks volumes of the little patience left in the Balkans.

It is hardly surprising. In order to get this far, North Macedonia had to resolve 27 years of disputes with Greece and change its name. Even then, France and Bulgaria continued to put up roadblocks. This had domino effects, stalling accession for Albania as well, since its application is twinned with that of North Macedonia. Bosnia and Herzegovina (BiH) is still stuck with potential candidate status, despite having gone through one of the most brutal wars in Europe and formerly being considered to have stronger prospects of joining the EU than Ukraine. Ironically, Kosovo, the country that usually displays the most pro-EU membership enthusiasm, stands last in line due to not being recognized by five EU member states and by Serbia. Kosovo's isolation within Europe has been exacerbated by the fact it is the only country within the Western Balkans not to have been granted visa liberalization by the EU, despite it meeting the required benchmarks back in 2018.

It’s not just leaders who are frustrated. In North Macedonia, former Prime Minister Zoran Zaev, who was initially credited with settling the country’s dispute with Greece and advancing its Euro-Atlantic prospects, was forced to step down in 2021 after voter frustrations with the stalled accession process led to a poor local electoral performance. Most recently, in July 2022, thousands of North Macedonians protested against the EU-led deal to settle the country’s dispute with Bulgaria. Although this painful concession opened way for the start of accession talks, more progress will be required to prove the Eurosceptics wrong.

In neighboring Kosovo, the EU’s broken promises have led to a loss of its credibility and decreased the normative power of the EU accession perspective. The fact that Kosovars are still unable to travel to the EU without a visa, despite having fulfilled more than twice as many criteria as many other countries, demonstrates how politicization, disunity and member-state interests have undermined the EU’s merit-based processes and that these processes are failing to reward reform.

The divergent accession standards applied to several Western Balkans countries have led to criticisms of EU double standards, and claims about the revival of historical prejudice and condescension.

Implications for democracy in the region

The stalled EU integration and the bloc’s broken promises threaten democracy in the Western Balkans. There are three reasons for this.

First, the process has helped fuel Euroscepticism, which has both undermined the efforts of the region’s progressive camp and strengthened the hands of its populists.

Second, the EU has been criticized for unintentionally promoting “stabilitocracies” and for not taking a stronger position against autocratic tendencies. One such example is in Serbia, where the EU has tolerated the democratic backsliding that has taken place under the administration of Aleksandar Vučić. Vučić might be the strongman who can deliver difficult concessions, but failing to call out his autocratic tendencies serves to weaken the democratic standards that the EU imposes on prospective member states and to frustrate those prospective member states, such as Kosovo and North Macedonia, who are implementing democratic reforms but are not being rewarded for doing so.

Third, the stalled EU integration process may encourage countries in the Western Balkans to seek out alternative partners, such as Russia, Türkiye and China, whose authoritarian influence is likely to weaken their democracies. Ties, in some cases close ties, with these countries already exist. The Kremlin considers the region to be in its strategic interest, and it has maintained close relationships with Serbia and BiH’s Republika Srpska, while opposing NATO membership for Albania, North Macedonia and Montenegro, and threatening Montenegro with long-range missiles. Erdogan has also signed free-trade agreements with all countries in the region, and Kosovo and Albania have been criticised for the unlawful deportation of ‘Gulenists’ to Türkiye. China has provided tech and military exports to the region, particularly leaning toward Serbia due to the similarities between the cases of Taiwan and Kosovo. Chinese investments in Serbia, BiH and Montenegro have raised concerns related to transparency, security, public health, and environment.

Democracy in the region had already been buffeted during the COVID-19 pandemic - amid cases of poor transparency in public procurement of medical supplies, government measures curtailing media freedoms, and limits on civil society - and was also challenged by a lack of solidarity in the EU response, where Türkiye and China seized the opportunity to gain ground offering their support.

The cooperation with autocratic powers might lead to other similar actions that threaten European standards and challenge the region’s contractual obligations with the EU. The Euroscepticism, establishment of stabilitocracies and the influence of autocratic powers in the region contribute to an increased isolation from democratic principles in the region.

A rejuvenated EU approach

Despite frustrations with its integration process, most countries in the Western Balkans still wish to join the EU. The overall persistence of pro-European attitudes, the delivered reforms, and the threats coming from external actors such as Russia, Türkiye and China, are reasons enough to inspire a rejuvenated EU approach towards the Western Balkans. Rewarding democratic leadership, consistently applying the EU’s democratic standards and taking a stand on democratic erosion should be guiding principles if confidence in the integration process is to be achieved. The commencement of accession talks with Albania and North Macedonia should be made a catalyst for further action, including Kosovo’s visa liberalization and clear guidelines for Kosovo’s and BiH’s paths to the candidate status. Making use of this momentum will be critical to fortifying democracy in the Western Balkans region and would drive the EU’s transformation into a more forthcoming and inclusive family.