Perspectives 'The most bitter cigarette': How Europe’s gas dependence is a hazard for democracy

The experience of the Southern Gas Corridor from Azerbaijan illustrates the risks as Europe tries to find alternatives to Russian energy.

Opinions expressed in this commentary are those of the author and do not necessarily represent the institutional position of International IDEA, its Board of Advisers or its Council of Member States.

How do we pay for the war? The European Union is broadly united in its political support for Ukraine as it defends itself from the Russian invasion, but policymakers have yet to come to terms with the fact that the real economic costs of this support must be distributed justly.

The stakes are high. As the side effects of sanctions against Russia reverberate around the world, and the war continues to disrupt key global supply chains, the reluctance to acknowledge and distribute these costs risks not only eroding international support for Ukraine, but real damage to the legitimacy of democratic governments themselves.

European governments have acknowledged that supporting Ukraine requires rearranging supply chains and absorbing refugees, but have been slow to address the real costs imposed by their dependence on Russian gas and coal. Italian Prime Minister Mario Draghi did broach the subject on 7 April when he framed the choice as being “between peace and air conditioning.”

Historically, high energy prices have been the market’s way of resolving this question in the absence of political intervention. Now, though, hastily implemented tax cuts and subsidies to major energy consumers could serve only to prop up fossil fuel companies and discourage badly needed investment in renewable energy.

Meanwhile, EU plans to substitute Russian gas with liquid natural gas imports from elsewhere carry their own risks. Anything other than “carbon austerity” will fail, warn Emily Holland and Marco Giuli in War on the Rocks. Without that, heightened competition for limited energy resources will “disproportionately hit importers in developing and emerging countries” and “[t]he Global South will find itself caught in the crossfire of a full-scale economic war between Russia and the West.”

Recent history also warns against trusting Europe’s skill at playing global gas geopolitics. Despite rosy predictions of breaking the continent’s dependence on Russia, and significant capital expenditures in new infrastructure to that end, Europe is as dependent on Russian gas as it was 15 years ago.

The Southern Gas Corridor

A vital part of this story is the Southern Gas Corridor (SGC), a USD 40 billion system of pipelines running from Azerbaijan to Italy, funded with USD 8.1 billion from international development banks.

The SGC was approved over widespread objections. International and Azerbaijani human rights activists argued that an influx of loans would prop up an autocratic regime just as its oil revenues were declining. Environmental activists worried both about the climate and local environmental impact.

Energy experts, too, were skeptical that Azerbaijan could produce enough gas to use the pipelines’ capacity, or that alternative suppliers would materialize to make up the remaining volumes. But public protests and closed-door lobbying failed to force even moderate deliberation of the wisdom of the project, and it went ahead. The pipeline shipped its first gas from the Caspian to Europe in December 2020.

In the region, these developments were interpreted through the lens of Azerbaijani “caviar diplomacy,” the well-documented practice of Baku taking advantage of corrupt Western policymakers, and gave credence to the notion that “European values” of democracy and human rights could be bought and sold.

History has, unfortunately, vindicated the critics. The pipeline is capable of meeting only a fraction of European energy demand, Azerbaijan is not capable of producing enough gas to fill it, and potential alternative suppliers continue to choose to sell their gas more profitably elsewhere.

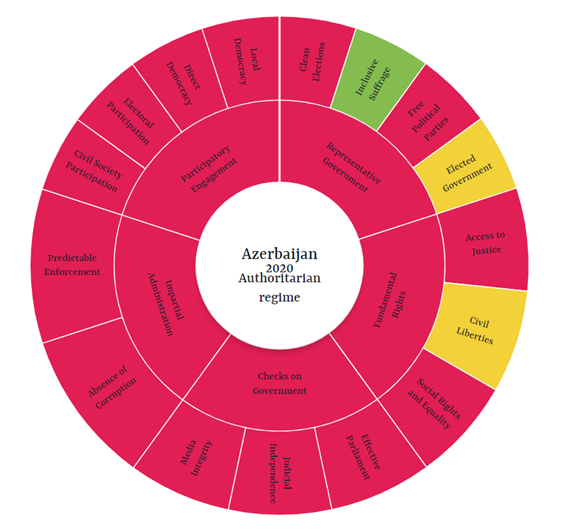

Confirming rights activists’ fears, the loans and subsequent receipts were lucrative for the Azerbaijani ruling elite, allowing it to further entrench its domestic economic and political position while funneling public wealth offshore. The years following approval were marked by an unprecedented crackdown on civil society and opposition groups.

The environmental worries were borne out, too. A January 2022 report by Crude Accountability documented the environmental toll on communities living near major Caspian gas facilities due to weak environmental protections and years of failures by all parties involved to implement them. “Early in the morning, when [gas] flaring has occurred, it feels like you smoked the most bitter cigarette,” one villager living near a major terminal south of Baku told researchers. “When it rains, it is as if dust and mud are falling from the sky.”

The loans and profits from the SGC also have compounded Azerbaijan’s resource curse—the well-documented process through which an influx of cash from extractive industries pushes weak democracies and authoritarian states towards further repression. The consistent decline of Azerbaijan’s oil production since 2010 should have been an opportunity for democratization, but instead the trends have been in the other direction.

Policymakers may have reasoned that democracy-building programmes and development assistance from foreign donors—of which Azerbaijan is a net recipient—would be sufficient to counterbalance the effects of the resource curse. The SGC provided Azerbaijan with the financial resources it needed to resist democratization.

Europe’s continued dependence on fossil fuels is an issue of national security, domestic and international inequality, and climate justice. This should not be a novel lesson, as Europeans saw the political consequences of an energy policy that tilts the costs towards the lower end of the wealth spectrum in the French gilet jaunes protests of 2018.

In a time of democratic decline, this is not a mistake the continent, or the world, can afford to make again.

This Commentary was originally published on euroasianet, 8 April 2022.