Pandemic states of emergency: Changing approaches over the course of the pandemic

With a novel virus quickly spreading worldwide in early 2020, many countries invoked emergency powers (either statutory or constitutional) to facilitate government responses. The legal mechanisms ranged from new legislation directed to this pandemic (as in Czechia and Germany), to the invocation of constitutional provisions originally envisaged for wars, insurrections, and natural disasters (see Latvia and Portugal for example).

In the first half of 2020, a number of legal and political scholars published articles that detailed the legal measures used in particular countries (see the excellent collection of posts at Verfassungsblog), and comparative analyses of the world (see posts at ICONnect and Harvard Law Review). Now, at the end of the first quarter of 2022, having faced at least four waves of rising and falling daily caseloads in most countries, we can better understand the connection between containing the pandemic and the use of emergency powers.

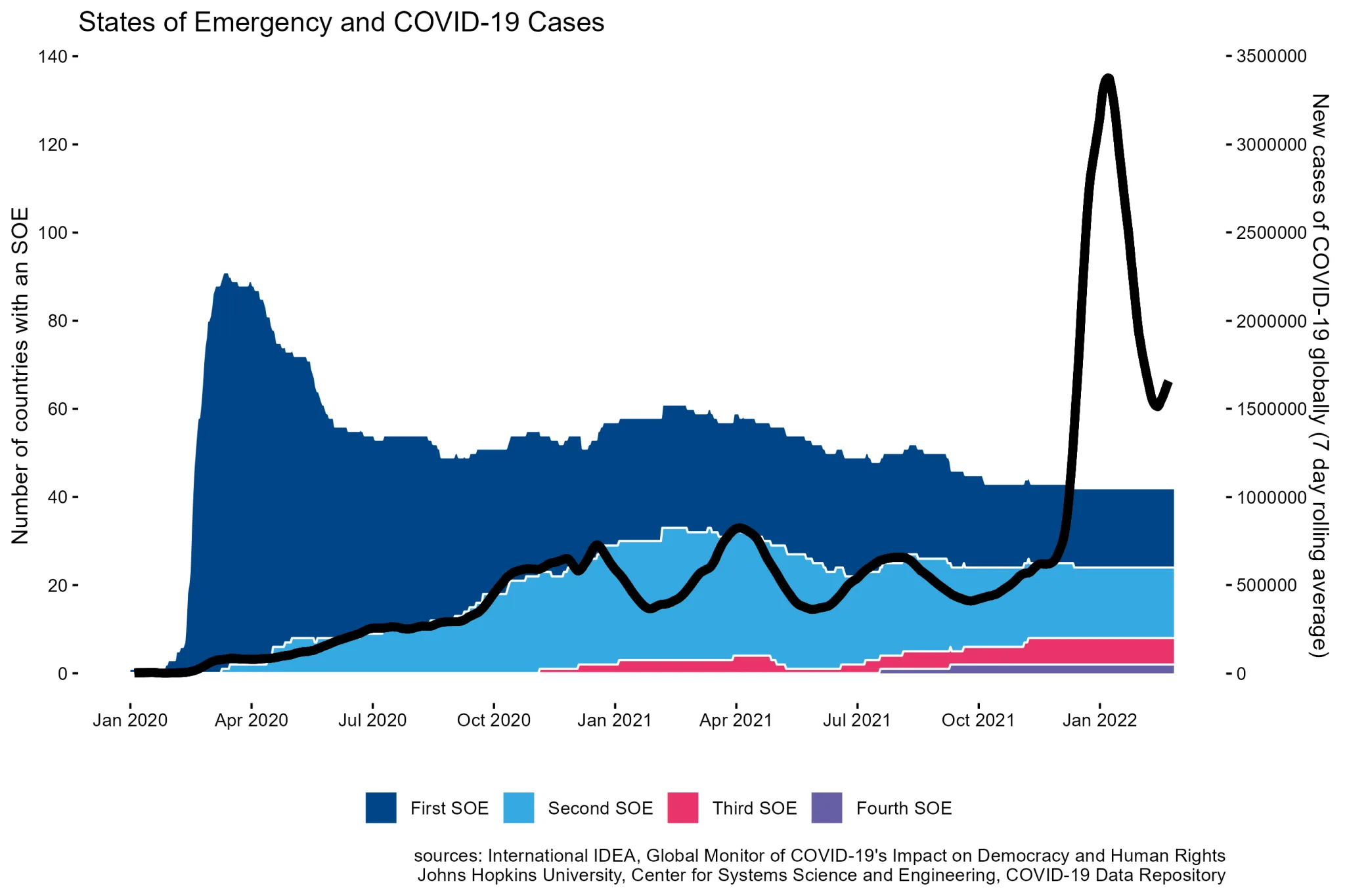

Data collected by International IDEA’s Global Monitor of COVID-19’s Impact on Democracy and Human Rights show how emergency legal responses changed over time. While many countries invoked a state of emergency (SOE), which in many cases allow for a temporary derogation of rights and give the executive more powers, in the first pandemic wave (as many as 93 in March 2020), relatively fewer invoked a full SOE in the second, third, and fourth waves (averaging 51 active SOEs after 1 July 2020). Some countries in which a first SOE had expired or been affirmatively ended in the middle of 2020 invoked a second SOE in the later months of the year. The relative stability in the number of active SOEs after August 2020 seems to indicate that the optimism of the summer of 2020 has been replaced by governments staying the course and repeatedly renewing a SOE. The surprising finding from our data is that the early peak in the number of countries invoking an SOE in response to the (relatively lower) caseloads of the first wave has not been matched as governments have sought ways to contain the much larger subsequent waves. However, there has been some variation here, as some governments responded to the Omicron wave by bringing in their third or fourth SOE of the pandemic.

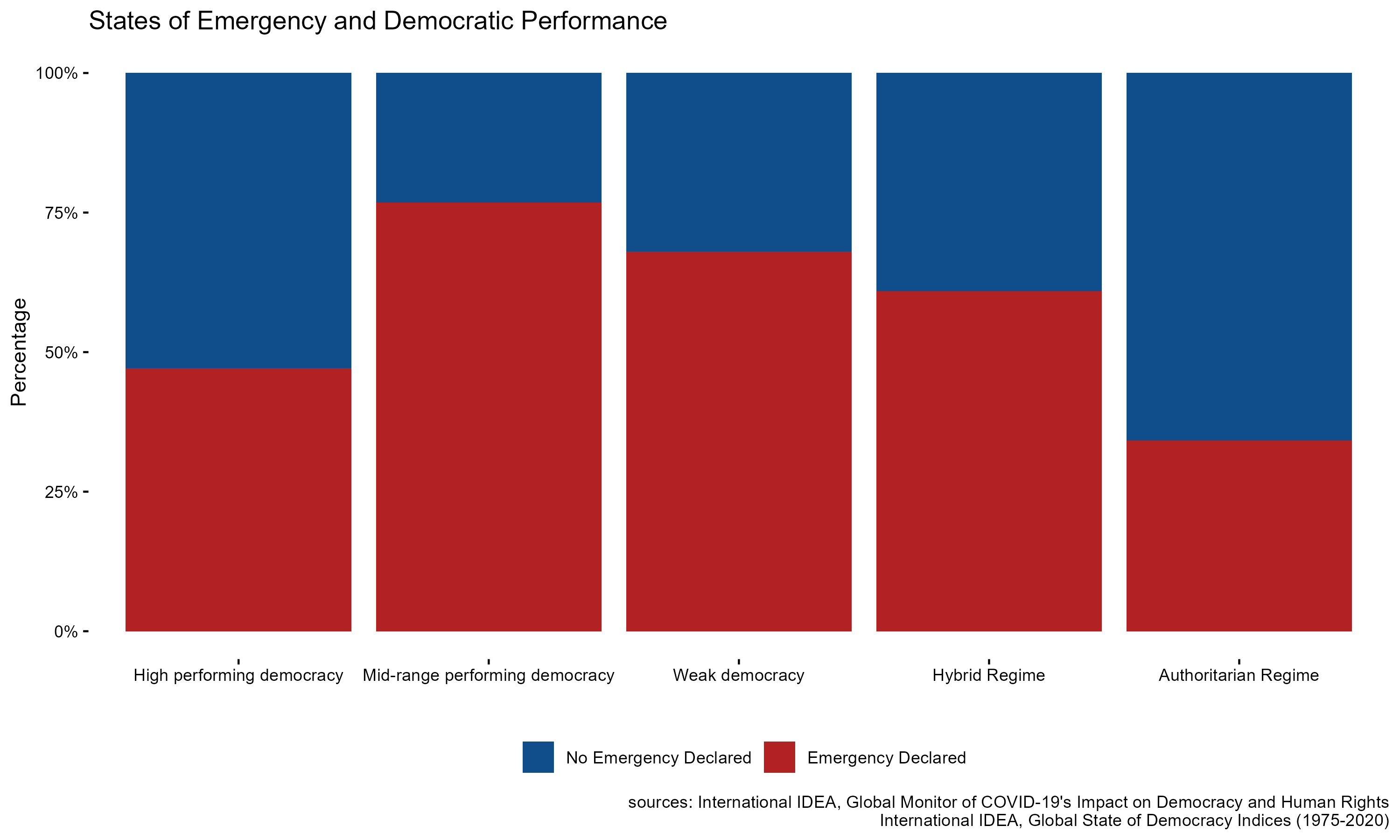

The characteristics of the countries where SOEs were declared are also interesting. What is most striking is relationship between the level of democracy as measured by the GSoD Indices and the use of emergency powers. Countries at the top and bottom of International IDEA’s democracy classification (i.e., high performing democracies and authoritarian regimes) were less likely to invoke an SOE. However, mid-range and weak democracies, and hybrid regimes, were more likely to invoke a constitutional SOE.

Authoritarian governments are unlikely to be as bound by constitutional or statutory constraints as even hybrid regimes, and certainly less than democracies. It may not be necessary to declare an emergency in order to impose significant restrictions on rights. In contrast, high-performing democracies are more likely to have a political culture that enables inter-partisan cooperation in moments of national peril, and to have a higher capacity within the government to respond to crises making the invocation of an SOE unnecessary. It is in the middle where the exigencies of the pandemic seem to have required an SOE in order to empower the government to take action.

The use of SOEs may also be predictive of how democracy may fare in various countries as the pandemic ends. High-performing democracies are likely to emerge from the pandemic with their institutions and political cultures intact. There is, however, some danger that the restrictions on rights (and particularly freedom of expression) instituted in weaker democracies and hybrid regimes may have longer lasting impacts on democratic consolidation. In particular, laws restricting freedom of expression and media freedom passed in some countries (for example in Azerbaijan, Belarus, Bulgaria, Hungary, Russia, Serbia, and Turkey) which were ostensibly created to deal with the wave of misinformation around the pandemic, could also be used to clamp down on dissenting opinions and aid anti-democratic actors now and in the future.