COVID-19 as an accelerator for information operations in elections

Disclaimer: Views expressed in this commentary are those of the authors. This commentary is independent of specific national or political interests. Views expressed do not necessarily represent the institutional position of International IDEA, its Board of Advisers or its Council of Member States.

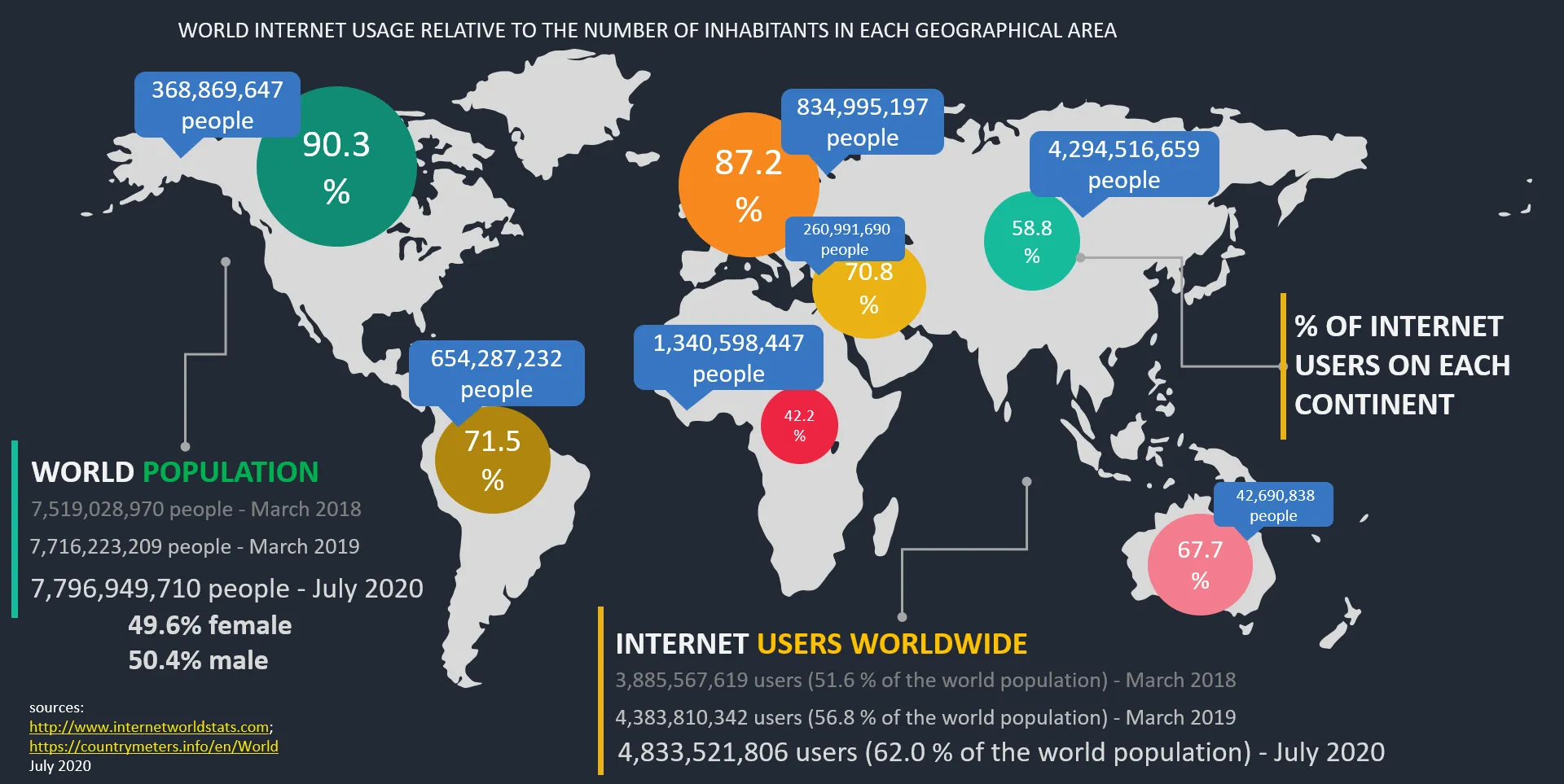

In the 1960s, the Canadian professor Marshall McLuhan coined the term global village[1] to refer to the interconnectedness of the planet that came along with advances in communications that allowed information to reach all corners of the world in real-time.

In 2020, the World Health Organization introduced the term infodemic[2] to describe the huge volume of information, often misleading, disseminated in the context of the novel coronavirus disease (COVID-19) pandemic.

As this infodemic sweeps through the global village it acts as an accelerator for information operations in elections and creates the need for election managers to develop new strategies and responses to a range of online challenges.