Can Turkey have credible elections? What the data reveal

Disclaimer: Opinions expressed in this commentary are those of the author and do not necessarily represent the institutional position of International IDEA, its Board of Advisers or its Council of Member States.

All eyes will be on Turkey when voters go to the polls on 14 May. This election, pitting incumbent President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan against opposition candidate Kemal Kılıçdaroğlu has been described as the most important election of 2023. There are high stakes, not least because it’s the first time in over 20 years that Erdoğan’s appeal in Turkey appears to have waned and that his defeat is no longer inconceivable.

Amid Erdoğan’s two decades of consolidated power and the dismantling of democratic norms in Turkey, there are questions about whether these elections can be credible and if the opposition stands a chance under these circumstances.

Opposition on the rise

There are signals that Erdoğan’s repression tactics are losing power, especially in a context marked by a plunging economy, rampant inflation, a collapsing currency, and the aftermath of the catastrophic earthquakes. As shown by most polls, public opinion has shifted toward the opposition, whose supporters might be too loud and too numerous to be defeated. Erdoğan is now competing against a six-party, more unified opposition led by Kemal Kılıçdaroğlu, an anti-corruption bureaucrat backed by Istanbul's popular mayor İmamoğlu and his Ankara counterpart, Mansur Yavaş. The opposition is also backed by the pro-Kurdish People’s Democratic Party (HDP) and influential Kurdish politicians, who could make up between 15 to 20 per cent of the electorate. Notably as well, Erdoğan’s opponents won most major cities in 2019’s local elections.

While Turkish voters have been polarized for years, and the elections may yet be held under unfair conditions with profound incumbency advantages, a strong, unified, and mobilized opposition has made competitive elections plausible, marking a critical juncture for Turkey’s future.

A Decade of Decline for Representation in Turkey

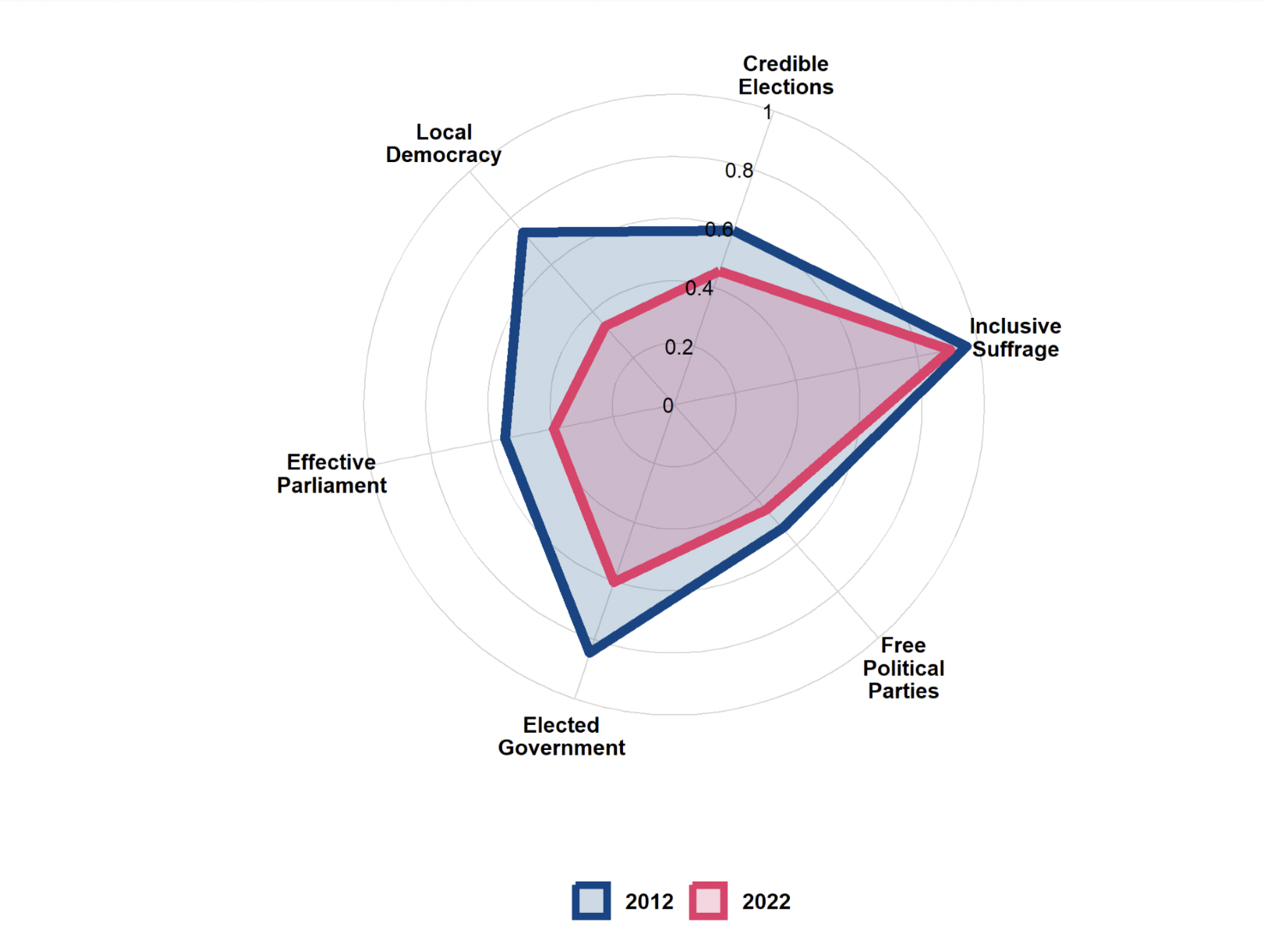

Global State of Democracy Indices data show regressions in all indicators related to elections since 2012. Issues such as credible elections and free political parties are part of the electoral cycle and are vital to the overall election assessment.

Source: Global State of Democracy Indices

Over the last 10 years, International IDEA’s Global State of Democracy (GSoD) Indices have shown a significant decline in clean elections in Turkey, particularly in factors such as the autonomy and capacity of electoral management bodies. The data also prompt questions about voting irregularities, government intimidation, and whether elections are credible. Observers also criticized the last election, held in 2018, for undue advantages favouring Erdoğan’s Justice and Development (AKP) ruling party, including excessive coverage by public and government-affiliated private media. In the lead-up to 14 May, it will be especially important to watch the media and freedom of political parties.

Crackdowns on media and other institutions

Reporters Without Borders estimates that 90% of the national media is under Erdoğan’s control. Over the years, Erdoğan’s administration has blocked access to social media, especially during critical moments such as the Gezi Park protests in 2013, the 2022 explosion in Istanbul and the February 2023 earthquake, the deadliest natural disaster in the country’s modern history. Following the earthquake, the government heavily sanctioned and fined the media for their coverage, particularly those bringing attention to the authorities’ responsibility for the quality of buildings that led to the high death toll, and the inadequate emergency response. Authorities have also arrested and sentenced activists and journalists, and the country’s parliament has passed a new ‘disinformation’ law in 2022, which has been criticized for cracking down on dissent ahead of the 2023 elections. The government has similar control over electoral authorities, public resources and institutions. The state budget has been an important platform for Erdoğan ahead of these elections as he announced a broad range of benefits, from a rise in wages to dropping the retirement age.

Unfree political parties

The GSoDI have also shown a significant drop in free political parties in Turkey over the last 10 years, with declines in the freedom to form parties, the autonomy of opposition parties, and electoral competitiveness.

Although Turkey’s political opposition remains strong in major urban centers, it deals with significant electoral challenges. In 2018, election observers with the Office for Democratic Institutions and Human Rights (ODIHR) declared that opposition parties were denied equal conditions for campaigning. With courts under his control, Erdoğan also employed more extreme tactics to sideline his opponents ahead of the 2023 elections. A court ruling sentenced Istanbul’s Mayor Ekrem İmamoğlu to two years and seven months in prison and banned him from political activity. Human Rights Watch called the verdict an “unjustified and politically calculated assault on Turkey’s political opposition.” Just as important is the new electoral law that was passed in 2022, which has been criticized for favouring AKP and its allies and for working against the opposition. The written opinion of the Council of Europe’s Venice Commission said the law could hinder inclusive democracy and the impartiality of elections, making it more difficult for smaller and newer parties to enter the parliament.