Q&A: Ahmed Abdirahman on the political participation of ethnic minority Swedes

Disclaimer: Opinions expressed in this commentary are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the institutional position of International IDEA, its Board of Advisers or its Council of Member States. This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

In this blog, we use the term ‘ethnic minority Swedes’ to refer to individuals with an immigrant background – defined here as those born abroad or born in Sweden with at least one foreign-born parent. This terminology reflects International IDEA’s choice of wording and differs from the language typically used by Järvaveckan Foundation, even though the underlying definition is the same.

Political participation is a cornerstone of democracy, yet engagement levels can vary across different communities. In Sweden, the district of Järva in the outskirts of Stockholm – home to a large proportion of ethnic minority Swedes1 – illustrates both the promise and the challenges of inclusive civic engagement. To explore these dynamics, we spoke with Ahmed Abdirahman, founder and CEO of Järvaveckan Foundation, who runs one of Sweden’s largest democratic forums dedicated to bridging the gap between citizens and policy- and decision-makers.

Järvaveckan Foundation is a non-partisan, non-political foundation that serves as a convening platform for dialogue across social, economic, and political divides. Through initiatives like the annual Järvaveckan event and Järvaveckan Research, Ahmed and the foundation have helped amplify underrepresented voices and strengthen engagement between communities and institutions. His work offers important lessons on how to strengthen democratic participation among underrepresented groups and ensure that all voices are heard in shaping Sweden’s democratic future.

What trends do you observe in political participation among ethnic minority Swedes?

In recent years, we’ve begun to understand political participation among ethnic minority Swedes with more nuance. For the first time, we (Järvaveckan Research) disaggregated voter data by country of birth and ethnic background, focusing on six of the largest non-European origin groups in Sweden: Somali, Eritrean, Ethiopian, Syrian, Iraqi, and Iranian.

Out of Sweden’s total population of 10.6 million, around 2.2 million are foreign-born. However, this is far from a uniform group. Just over half – 56.6 percent – were born outside of Europe, and among them, the vast majority have roots in either Asia (68.4 percent) or Africa (20.2 percent). Within the Asian group, Syria, Iraq, and Iran account for 53.4 percent, while in the African group, Somalia, Eritrea, and Ethiopia make up 59.5 percent. Together, these six countries represent nearly half of all foreign-born individuals from outside Europe (48.6 percent) and 27.5 percent of the total foreign-born population in Sweden.2

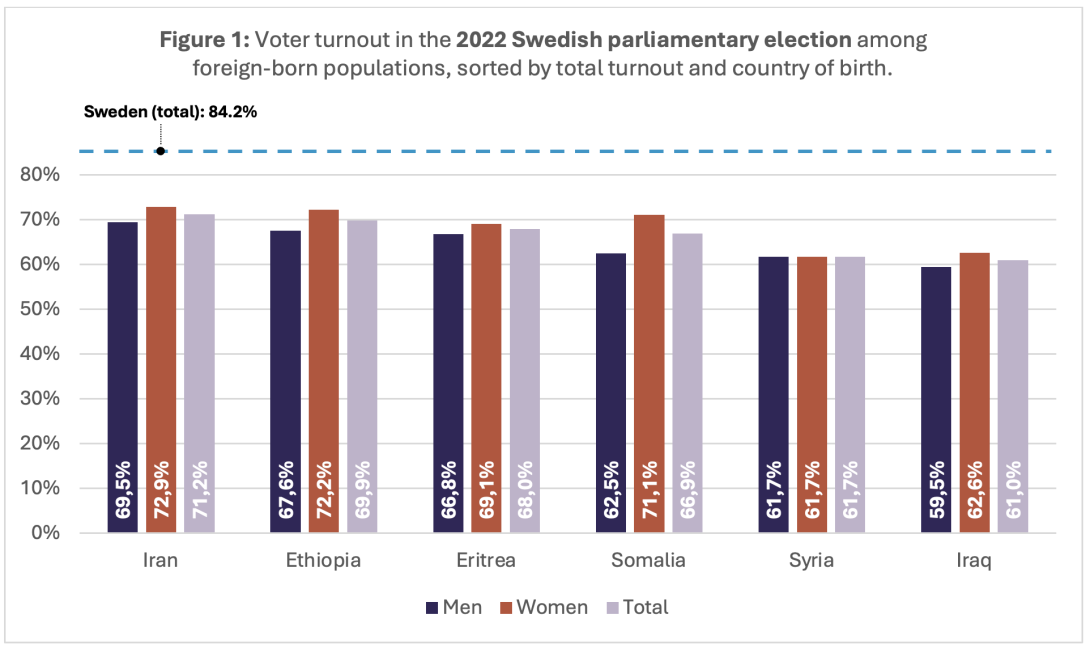

Our guiding principle is simple: what we can measure, we can improve. The data shows a consistent trend: voter turnout among Swedish citizens born outside the country – and their Swedish-born children – is lower than the national average (see Figure 1). However, the story doesn’t end there. When national turnout rises, so does turnout in these communities. When it dips, it falls with it. This shows that broader political engagement affects everyone.

We also found that women vote at a higher rate than men – a pattern consistent globally. Still, even among high-performing groups [among the ethnic minorities of Sweden], turnout rarely reaches the national average. This gap poses a concern in a democracy that prides itself on equality and participation.

Our research also challenges assumptions that Swedes with immigrant background uniformly support left-leaning policies. On questions of law and order, for instance, many communities tend to favor stricter penal codes. They express frustration over rising crime and what they see as lenient sentencing. These views are not ideological outliers, but responses rooted in lived experience.

What are the biggest barriers to higher engagement, and how can they be addressed?

One major barrier is not being seen as part of the electorate. Political parties often overlook these communities, failing to engage with them meaningfully. When people don’t feel heard or included, participation suffers. While discrimination exists in many arenas, including the labor market, voting is the one area where every individual’s voice carries equal weight. That is something worth protecting – and encouraging.

For several, there’s also a lack of democratic experience. Some newcomers to Sweden come from countries where voting either hasn’t existed for decades or where elections lack credibility. This can shape one’s perception of whether voting makes a difference.

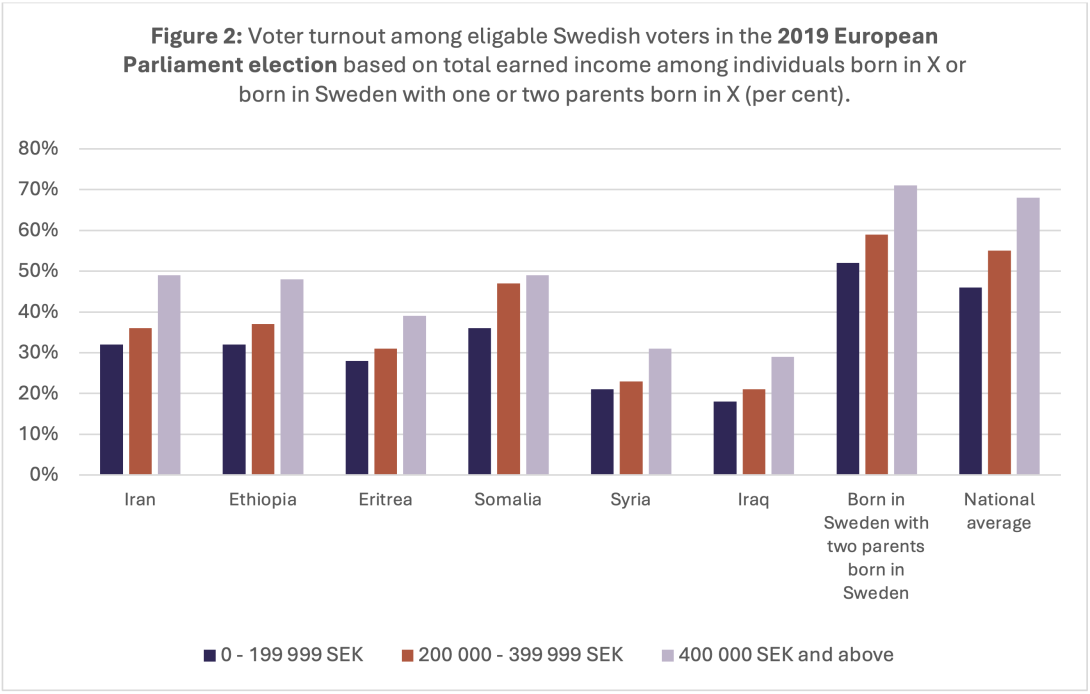

Socioeconomic factors play a huge role as well. Voter turnout increases with education and income3. In the 2019 EU elections, only 47 per cent of Swedes earning under SEK 200,000 voted, compared to 68 per cent of those earning over SEK 400,000 (see Figure 2). These figures are echoed across all groups, regardless of origin.

One challenge is that people with a foreign background – whether born in Sweden or elsewhere – are often the subject of political and public debates framed narrowly around migration, integration, or criminality. Increasingly, topics like the labor market, gender equality, and values are being folded into this discourse. As a result, this group is often in the eye of the political storm, which can breed disengagement or mistrust.

While language is sometimes cited as a barrier, we believe the deeper issue is how politics is communicated. If debates are overly technical or disconnected from daily realities, many voters tune out – not because they don’t understand Swedish, but because they don’t feel addressed. And while language barriers are often cited, our understanding is that many ethnic minority Swedes understand Swedish well. The perception that they do not is largely anecdotal and unsupported by rigorous data.4

Lastly, it is however worth noting that some parties are beginning to engage with ethnic minority Swedes more intentionally. While they have long targeted traditional demographic groups such as the elderly or rural voters, they are now beginning to view ethnic minority Swedes – and particularly those born outside of Europe – as a distinct and diverse voter group worthy of tailored outreach.

Do you see differences in political participation between first- and second-generation immigrants?

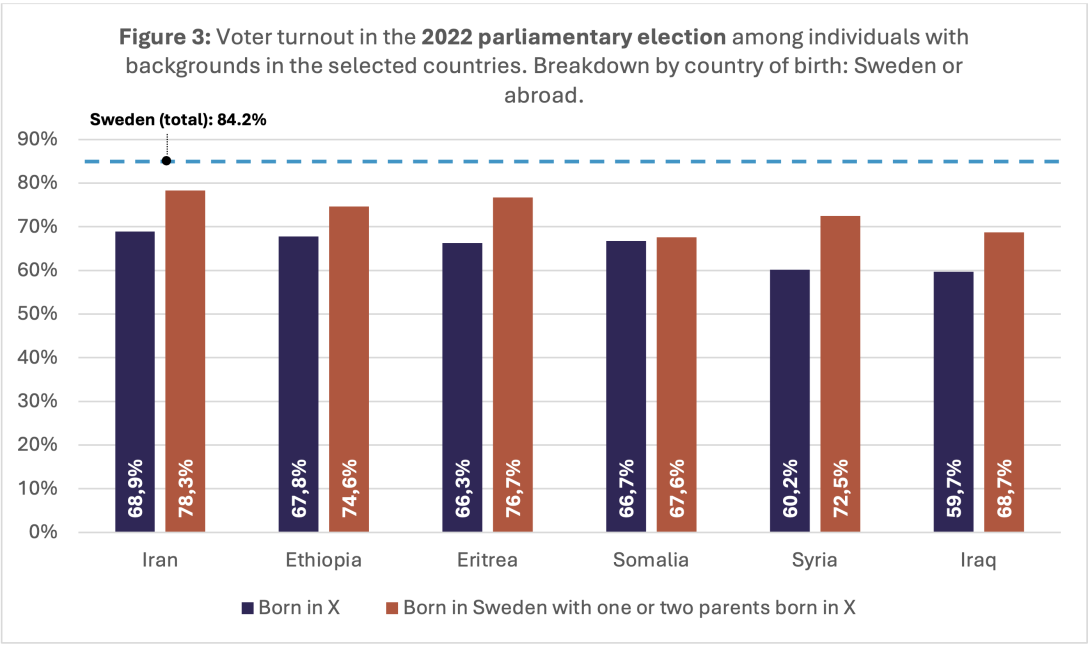

Yes, generally speaking, those born in Sweden to immigrant parents tend to vote more than those who immigrated themselves. This makes sense – they grew up here, went to Swedish schools, and are more likely to feel a sense of belonging (see Figure 3).

But this isn’t always the case. In some communities, like among Swedish-Somalis, we found very little difference in turnout between generations during the 2022 elections. In fact, some second-generation individuals feel more disconnected than their parents, caught between identities and not fully accepted in either space. This highlights a deeper issue: we risk losing a generation of voters if we don’t create pathways for genuine inclusion and engagement. And without disaggregated data, we wouldn’t even know where these gaps exist.

It’s also crucial to remember that identities and preferences evolve. There is a tendency to view ethnic minority Swedes as static, or to essentialize them based on culture or origin. This is particularly true for individuals born outside of Europe. But just like everyone else, their views shift with time, context, and life experience.

What factors influence these generational shifts in civic engagement?

A major factor is how long someone has lived in Sweden. Many people who immigrated here in the 90s or early 2000s have now spent most of their lives here, yet they’re still often perceived as outsiders. That sense of exclusion doesn’t disappear just because someone speaks fluent Swedish or holds citizenship.

Family dynamics also matter. In many households, you have three generations with different views on society, identity, and politics. Yet these differences are rarely acknowledged by political leaders or journalists. We see them clearly in our surveys and believe they must be part of the public conversation.

Another important element is representation. When young people don’t see people like themselves in positions of influence, it affects their sense of political efficacy. This is why visibility and role models are so important.

What strategies have proven most effective in fostering greater political participation?

At Järvaveckan, we meet people where they are. We create multiple entry points for engagement – through music, food, and culture – and then weave in dialogue around democracy and politics. Many young people come for the artists but leave having spoken to a politician, a police officer, or a private sector representative.

We’ve also translated political speeches into other languages when needed, although many people understand Swedish far better than is often assumed. What matters more is making content accessible, not just linguistically but contextually.

We regularly survey communities across Sweden to find out what issues matter most to them – be it jobs, housing, or security. These insights help us bridge the gap between political parties and underrepresented voters. People want to be heard on a range of issues, not just on topics like migration or integration. They care about taxes, the environment, gender equality, entrepreneurship, and more. This has helped challenge the notion that ethnic minority Swedes are a monolithic group.

What role do community initiatives like Järvaveckan Foundation play in shaping inclusive democracy?

Our strength as a society lies in our ability to cooperate across differences. But that requires physical spaces where people can meet, interact, and build trust. Järvaveckan creates that space. In 2024 alone, we welcomed over 60,000 visitors and 300 participating organizations from civil society, government, and the private sector.

In a highly segregated and increasingly atomized society – where many Swedish households5 are single-person homes – this kind of face-to-face interaction is vital. It allows people to see each other as individuals, not just statistics or stereotypes. That human connection, more than anything, can transform apathy into engagement.

Ultimately, we believe democracy is not just about voting. It’s about belonging. And belonging begins with being seen, heard, and valued.

The next edition of Järvaveckan will take place between 11 and 14 June 2025 in Stockholm, Sweden.

[1] Järvaveckan Foundation defines this as people with ties to another country – either through being born abroad or having one or both parents born abroad. This differs slightly from the official Swedish definition of foreign background, which includes only those born abroad or born in Sweden with both parents born abroad.

[2] These figures do not include children born in Sweden to one or two parents from these countries.

[3] A total of 80,903 individuals were living with low economic standards in Sweden in 2021. Of these, just over 60 per cent had a foreign background, while the remaining 40 per cent were born in Sweden with both parents also born in Sweden. Low economic standard is defined as individuals living in a household with a disposable income per consumption unit that is less than 20 per cent of the median for the entire population. Disposable income refers to the sum of all household income. The median in 2021 was SEK 271,400 per household, year, and consumption unit (20 per cent = SEK 54,280) (Järvaveckan Research & PwC Sweden, 2023).

[4] The collection and use of equality data based on racial or ethnic origin is limited in the Swedish context (The Local 2024)

[5] According to Statistics Sweden's population data from 2024, 41.7 per cent of all households in Sweden consist of a single person – one of the highest figures across Europe.