Explainer: Populism - Left and Right, Progressive and Regressive

Disclaimer: Opinions expressed in this commentary are those of the author and do not necessarily represent the institutional position of International IDEA, its Board of Advisers or its Council of Member States.

For many observers of politics in Europe and the Americas in 2022, the combination of words that forms “right-wing populist” trips easily off the tongue. Right-wing populist politicians, such as Jair Bolsonaro, Narendra Modi, Viktor Orbán, or Donald Trump, are frequently named as such in the press. But populism is an approach to politics—not a singular and comprehensive theory of governance. It is, in fact, a tactic that has long been used around the world, at least since the nineteenth century, to gain and maintain power.

What is populism?

It is difficult to definitively characterize populism, but one helpful definition describes it as “reflecting a deep suspicion of the prevailing establishment, which is believed to conspire against the people instead of working in their interests.” Populists believe that the people, however defined, are the “true repositories of the soul of the nation.” Donald Trump’s frequent references to his supporters as “real” Americans are a classic populist rhetorical move.

The concept of populism has a distinctly pejorative connotation. It is a label that politicians apply to their opponents, but rarely claim for themselves (as Mudde and Kaltwasser aver). The fundamental claim of populism is that there is a singular “people” who are in opposition to “the elite.” The populist claims to be the representative of “the people.” In this way, a populist movement would describe itself as authentically democratic—in contrast with the “politics as usual” that only supports the interest of “the elite.”

Populists can be from the right or left of the political divide; left-wing populists (also known as social populists) combine left-wing politics with populist themes and rhetoric while right-wing populists (also known as national populists) do the same on the right side of the political spectrum. Writing about Western Europe in 2018, Chantal Mouffe argued that the “central axis of political conflict will be between right-wing populism and left-wing populism.” Populism does not always have to be extreme, but it is almost never centrist. For example, populist appeals have been commonly found in Canadian politics, coming from the left-wing New Democratic Party and from the right-wing Conservative Party (and its predecessor in the form of the Reform Party), but not from the centrist Liberal Party.

While both left-wing and right-wing populists object to the perceived control of liberal democracies by elites, those on the left also have problems with large corporations and their allies while those on the right focus on external threats. Left-wing populists perceive the enemy of the people to be socio-economic structures rather than particular groups of people. Right-wing populists define the enemy of the people to be “other” people, such as immigrants, refugees, etc. They tend to be skeptical of the facts presented by the establishment press, may be suspicious of intellectuals and want to be from “somewhere” as opposed to “anywhere.” That is, they want to be rooted in a specific community and place, as opposed to being comfortable nearly anywhere.

The recently completed second-round presidential election in Brazil is a case in point: both candidates can reasonably be characterized as populists, one from the left and one from the right.

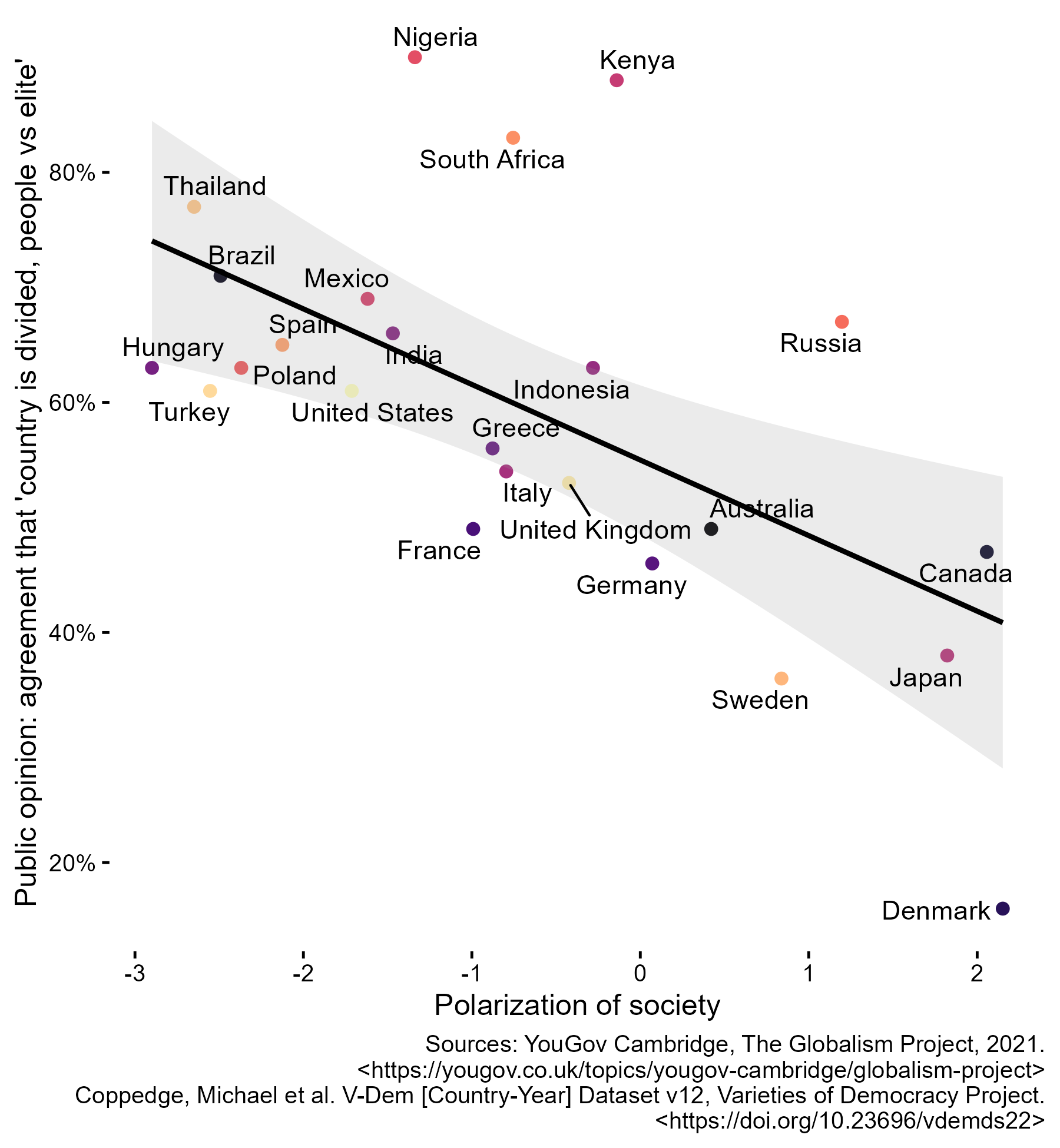

Though it may appear to be a recent trend, populism has been around for a long time. One study shows that it can be serial in nature. It is also closely related to societal polarization. As the graph below illustrates, public opinion regarding the division of society between “ordinary people and the corrupt elites who exploit them” is highly correlated with social polarization (negative scores here indicate a more polarized society).

Why is populism a threat to democracy?

Right-wing populism’s incompatibility with democracy is clear when one carefully considers who “the people” often are in the populist imagination. They are not all the people. They are the minimum winning coalition of the people, and usually a part of the people that are defined in terms of their ascriptive characteristics (e.g., white). Such an exclusionary view of “the people” cannot be reconciled with democracy’s requirement of political equality.

The picture for left-wing populism looks rather different, lacking this prima facie contradiction with democracy. As an example, the Workers’ Party (PT) in Brazil has built a notably diverse coalition of support, still making the claim that the party represents the interests of “the people” against the elite. However, the claim that a party or politician speaks for the authentic and singular people can become difficult to square with democracy, as the descent of Venezuela into authoritarianism under the left-wing populist Hugo Chavez illustrates.

As an ideal, democracy includes all the people, considered as equals, finding a collective path toward the best possible policies to address the challenges that they face.