Political Finance in the Digital Age

Towards Evidence-Based Reforms

Digital campaigning is on the rise across the world, and political parties and candidates spend more of their financial resources online. Other aspects of political finance—such as fundraising and reporting of parties’ and candidates’ finances—have also moved to the digital realm. While this trend creates new opportunities for reaching voters and for political participation, regulators are confronted with new challenges in their approach to this phenomenon. Existing regulatory frameworks are often insufficient to cope with the digitalization of campaign finance and need to be adapted. Yet many questions remain on how the rules should be changed and which regulatory approach should be followed.

This report offers an overview of the recent developments regarding digital campaign finance. Building on insights and findings from in-depth case studies—on Albania, Belgium, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Brazil, Chile, the European Union, India, Kosovo, Mexico, Montenegro, Nigeria and the United States—it discusses the main challenges faced. While these countries might differ in their specific political and electoral contexts, they experience very similar regulatory difficulties. Studying these cases enables the identification of best practices and possible lessons that can be drawn for political finance oversight bodies, civil society organizations, political party officials and legislators worldwide.

After an introductory section, the first part of this report discusses the current landscape of online campaign finance and identifies the main regulatory choices that exist: from a total ban on online campaigns, to incorporating the digital aspects into the rules on traditional campaigning, to the development of specific rules for online advertising. Regulators can opt for self-regulation or binding rules and can concentrate their regulatory efforts on political actors or online platforms. In the second part of the report, the most important issues in the regulatory framework governing online campaign finance are discussed. These include the full extent of the definition of digital campaigning, the differences in regulating online and physical campaigns, and the difficulties regarding official campaign periods and the concept of electoral silence.

The third and fourth parts of this report focus on the oversight of online campaign finance, with particular attention given to the role of monitoring agencies, civil society organizations, the media and online platforms. The fifth part goes into the main regulatory challenges, such as online third-party campaigning and in-kind contributions, cross-border campaigning and foreign interference, microcredits and cryptocurrencies, and the use of influencers and digital marketing firms.

The report concludes with a number of recommendations:

- The transparency of digital campaign finance should be increased, at the level of the online platforms as well as the oversight bodies, political parties and candidates. The further development of online advertisement repositories and transparency notices linked to online advertisements can improve the monitoring of digital campaign finance. Similarly, a wider definition of digital campaigning and a higher degree of granularity in financial reporting can improve oversight.

- Third-party campaigning should be included in the regulatory framework, by incorporating this into existing rules on campaign finance or by developing a specific new set of rules. Compulsory registration, the use of a dedicated bank account and financial reporting are only some of the provisions that can be considered.

- Better oversight of external media companies can strengthen overall campaign monitoring—for example, by setting up a public register of suppliers of external communication and public relations (PR) services for both online and offline political campaigns.

- Rules should also clarify the differences between ‘organic’ digital content and funded online political campaigns, and ideally create a level playing field between the digital and physical elements of electoral campaigns. The limits and possibilities of organic digital campaigning are an important point of attention in this respect.

- The capacity of oversight bodies should be strengthened to foster the specific expertise needed to monitor digital aspects of electoral campaigns. One important capacity-building strategy is the development of specific programmes to improve specialized knowledge and expertise in the control bodies, such as database management, data compilation and analysis, social media communication analysis, cybersecurity and information security, and financial transaction technology.

- It is also important to strengthen the capacity of civil society organizations, which fulfil a key role regarding oversight of digital campaign finance. The introduction of user-friendly and accessible tools for monitoring can also be helpful, as well as capacity-building programmes regarding tracking and monitoring online campaign finance, and the analysis of financial disclosure reports.

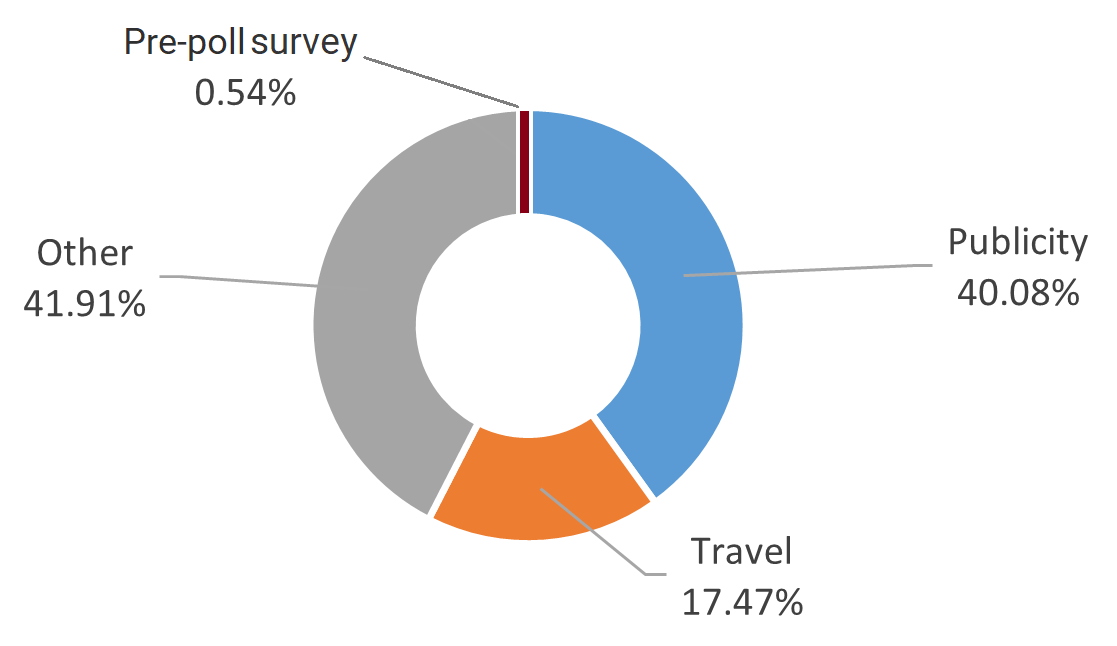

Politics is increasingly a digital affair: many aspects of political organization and electoral campaigning are shifting online. This is an inevitable part of the ongoing digitalization of society as a whole. In all countries in the world, Internet use is consistently on the rise. In 2024, global Internet penetration was at around 66 per cent, meaning that two-thirds of the world’s population have access to the Internet. In Western countries, Internet use stands at greater than 90 per cent (Kemp 2024). It is therefore not surprising that there is remarkable growth in the use of digital tools and social media platforms for political and electoral campaigning. Many have even argued that we have entered a new era—or ‘fourth phase’—of data-driven political campaigning, fuelled by the collection and analysis of large amounts of individual-level data with the purpose of microtargeting groups of voters (Gibson 2020; Kefford et al. 2023; Magin et al. 2017). Almost all 13 case studies analysed in this report show an increase in the financial resources that are spent on the digital aspects of campaigning, especially on social media platforms. The most striking example might be the USA, where it is estimated that more than USD 2 billion was spent on online advertising in the run-up to the 2020 elections (Venslauskas 2024). In Brazil, social media expenditure during election campaigns increased from approximately EUR 19 million in 2018 to EUR 69 million in 2022, largely at the expense of more traditional forms of campaigning (such as television and radio advertisements and sound trucks and cars) (Grassi 2024).

In some countries, more traditional forms of campaigning are still dominant, but most experts expect the digitalization of politics to spread everywhere. For example, in Belgium, investments in more traditional campaign tools are still in the majority, but the use of online advertising is on the rise. There are also substantial differences across parties in the country, with the far-right party and some liberal and socialist parties spending a higher proportion of their campaign budgets on online advertisements. Expenditure on digital campaigns from individual candidates, on the other hand, remains relatively limited (Vanden Eynde 2023).

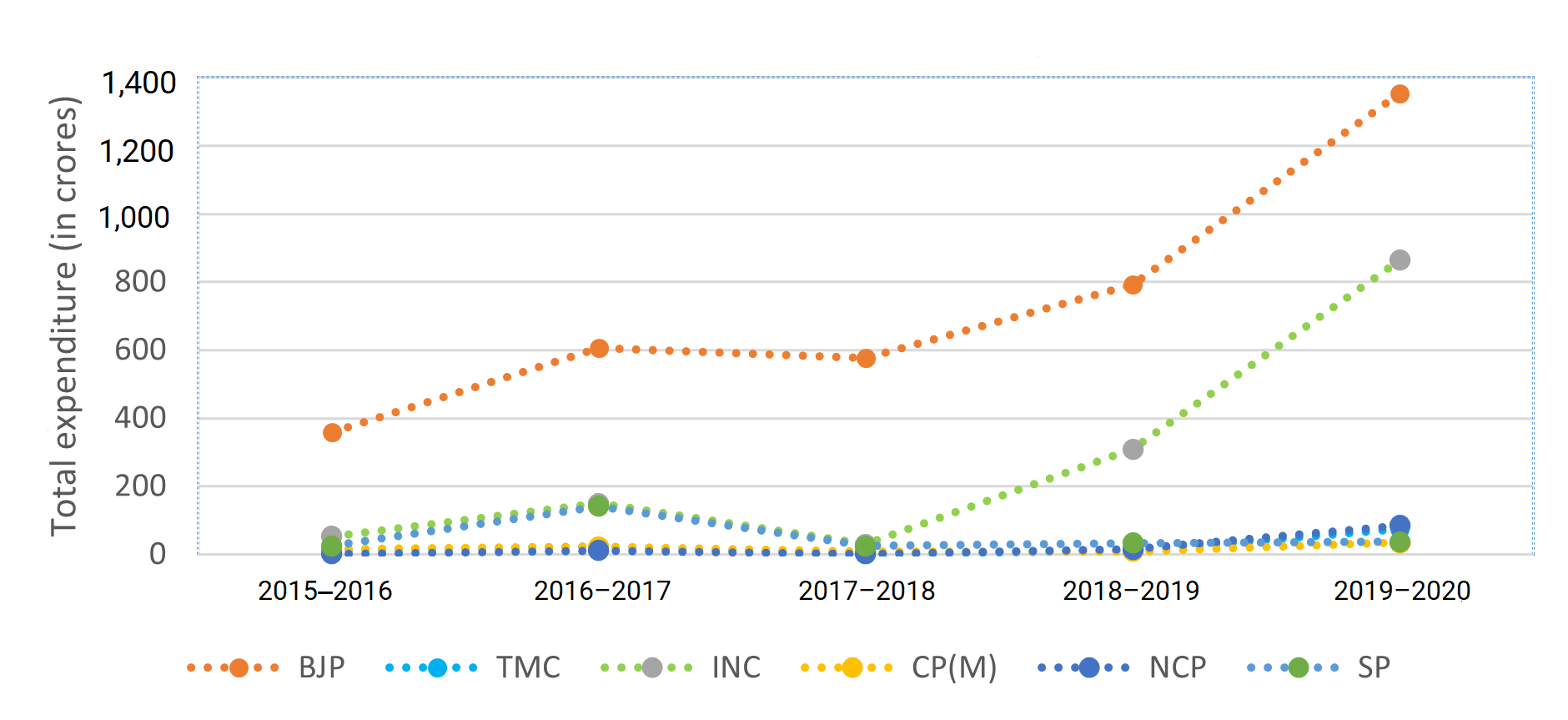

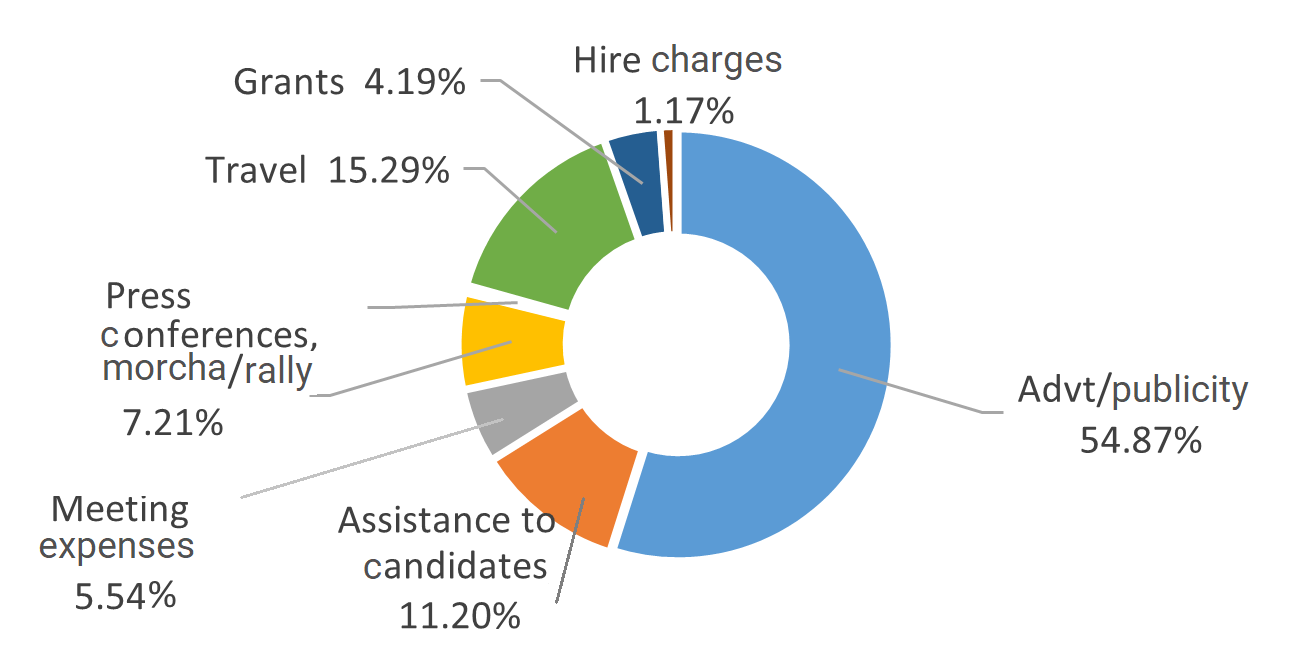

India has been characterized by increased use of social media platforms for political advertising. The general elections of 2014 were the first time that big data analytics were used in political campaigns for the profiling and targeting of voters (Rao 2019; Sahoo 2024; Sen, Naumann and Murali 2019). The 2019 elections saw an estimated total campaign expenditure of USD 8.7 billion by all parties and candidates, and an estimated USD 8.3 million on online advertising on Google and Meta platforms. This relatively modest share, however, does not include the expenses of content development, or salaries or fees for social media staff or fees of the professional agencies. Since 2019, there has been a growing shift in the parties’ strategies towards using digital campaigning, which seems at least partly driven by the massive growth in Internet and social media users. More than half the country’s population now has access to a smartphone and social media channels (Sahoo 2024).

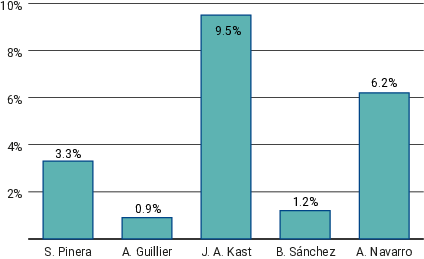

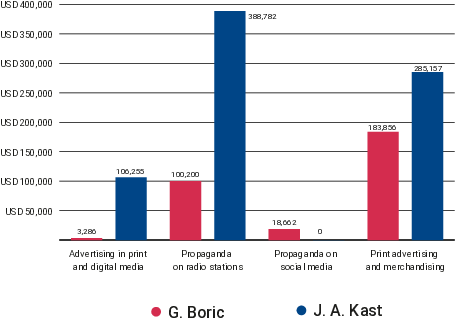

In some countries, the global pandemic of 2020–2022 has generated a profound transformation in political campaign strategies, since in-person and print media campaigns were substantially hampered (International IDEA 2020). Chile experienced five electoral campaigns in the period from 2020 to 2023, and social distancing measures were in force during much of this period, limiting the possibilities of physical campaigning. As a result, digital advertising—through social media platforms, automated calls, mass text messages and the use of artificial intelligence—replaced traditional forms of campaigning, such as rallies or billboards (Jaraquemada 2024; Olave 2021). In Montenegro, the 2020 parliamentary elections amid the Covid-19 crisis were marked by a tenfold increase in advertising costs on social media by political parties, compared with the previous elections, although these expenses are overall lower than for traditional media (Kovačević forthcoming 2025).

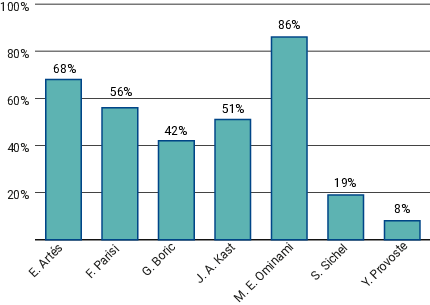

In most countries, Meta platforms seem to attract the bulk of campaign expenditure, although other online platforms are becoming increasingly popular. During the general elections in Chile in 2021, Meta platforms were used by all candidates for political advertising (Jaraquemada 2024). In Nigeria, Facebook/Meta is one of the most popular social media platforms and the preferred platform for accessing news online. It is therefore not surprising that most national politicians have a strong presence on the platform; as early as 2010, President Goodluck Jonathan of the Peoples Democratic Party announced his campaign to run for president on Facebook (Adetula 2024). In Brazil, Meta platforms (Facebook and Instagram) were the most popular for political campaigning, accounting for more than 80 per cent of social media expenditure by political actors in the 2018 general election and 2020 municipal elections. In the 2022 general election, this share dropped to approximately 60 per cent, with Google obtaining a higher share of political expenditure. Other social media platforms like TikTok and Kwai were not widely used (Grassi 2024).

Nevertheless, there are often specific features of a country that provide a unique context for its online campaigning. For example, in India, there has been a rapid expansion of social media applications in different regional languages, which are used by the political parties to specifically target certain subgroups in society (Sahoo 2024).

A further consideration is the extent to which digital campaigning differs in any fundamental way from more traditional campaign tools. On the one hand, both revolve around the same thing: communication from parties and candidates to voters in an attempt to secure their support. And in this respect, the pertinent question is how political actors differ in their use of resources to finance their campaign activities, and how this affects political competition more generally. Do digital technologies make campaigning cheaper and more efficient, benefiting smaller and less established parties and creating a level playing field, or can wealthier parties take advantage of their additional financial resources in the digital realm as well, thereby compounding pre-existing inequities (Gibson and McAllister 2015)?

On the other hand, there are important differences between digital and traditional campaigning. In some cases, a much larger audience can be reached through automation technologies. Compare online advertisements, automated calls and mass text messages with door-to-door canvassing and physical election posters. These new forms of campaigning often require fewer human resources and so create an advantage for parties and candidates that can rely on substantial financial resources but have fewer volunteers and/or members.

At the same time, in terms of reach, online advertisements are comparable with more traditional political commercials on radio and television. But the speed with which certain political messages are circulated online is often quicker, and this raises specific concerns with regard to the spread of political disinformation and fake news. In addition, it might become increasingly difficult for citizens to recognize something online as a political advertisement, since important information about the sponsor is usually missing. Similarly, the digitalization of political campaigning increases the possibilities for cross-border campaigns and thus also the risk of foreign interference, since it is less linked to the physical location of the person or organization running the advertisement.

The most important difference might be the wide range of possibilities for personalizing advertisements that social media platforms in particular offer. Targeted political advertising—especially microtargeting—relies on the collection and analysis of sensitive personal data to identify the interests and preferences of a specific audience, so as to be able to adjust the campaign message accordingly, with the aim of maximizing the influence on recipients’ voting behaviour (Bashyakarla et al. 2019). Such a level of personalization is not possible with more traditional forms of campaigning, like commercial billboards or television advertisements. In addition, political actors might engage in not only what Roemmele and Gibson (2020) describe as ‘scientific’ campaigns—aimed at informing and mobilizing voters—but also ‘subversive’ campaigns, with the objective of demobilizing voters and/or providing misinformation. The latter form of advertising creates fundamental democratic challenges. These problematic aspects of online campaigns might affect electoral integrity and have long-term implications after the elections (Agrawal, Hamada and Fernández Gibaja 2021).

In addition to the expenditure side of electoral campaigns, digital technologies are increasingly utilized by political parties and candidates for fundraising activities. On the plus side, these technologies offer new ways of campaign fundraising, such as microcredits or crowdfunding; however, they also bring new regulatory and oversight challenges. First, Internet platforms facilitate cross-border fundraising, which increases the risk of foreign funding and—consequently—the potential for foreign interference. Second, the use of digital technologies sometimes makes it more difficult to track financial transactions, especially when large-scale fundraising techniques, such as crowdfunding, are used. A particular problem in this respect is the emergence of cryptocurrencies—Bitcoin is probably the most well known. Such decentralized currencies bypass the traditional banking system, which creates important limitations for financial oversight (Venslauskas 2024).

Digital campaigning thus creates new challenges for regulators all over the world. One view of money in politics is that it is always looking for ways to break through the regulatory framework containing it, and the online environment can be considered one of the largest weaknesses in the overall system, with the potential to circumvent certain restrictions and limitations (Issacharoff and Karlan 1999; Power 2024). According to International IDEA’s Political Finance Database, less than 10 per cent of countries worldwide have specific provisions concerning online expenditure (International IDEA n.d.). Regulators need to be able to strike a balance between ensuring fair political competition and electoral integrity on the one hand, and respecting fundamental rights like freedom of expression on the other.

The objective of this report is to examine the main trends in online campaigning, how countries have, and have not, adapted to this new reality, which regulatory changes can be considered best practices and how the rules can be improved further to tackle the most important risks of digital campaign finance. This is done through the analysis of a number of instrumental case studies (on Albania, Belgium, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Brazil, Chile, the EU, India, Kosovo, Mexico, Montenegro, Nigeria and the USA), expert interviews and additional desk research.

The selection of case study countries was guided by several key factors. While regional balance was considered to allow for diverse perspectives and experiences, the selection prioritized countries where there have been notable progress or ongoing discussions on political finance reforms that address digital aspects, ensuring that the report captures emerging trends and regulatory efforts—the rationale why many of the countries are from Europe, a region which has made significant strides in this area. Lastly, the relative influence of each country within its region was considered, focusing on nations whose experiences and policies could serve as models or have a broader impact on regional discourse.

The case studies were developed between October 2021 and August 2024. While every effort has been made to include relevant regulatory updates across the 13 countries, the rapidly evolving nature of this field means that some recent developments may not be fully captured.

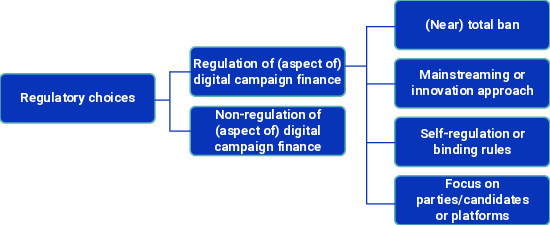

The rise of digital campaigning has created new questions and challenges for regulators, and authorities all over the world have taken different approaches, in particular on social media platforms (Figure 1.1). The first core question is whether or not a particular aspect of digital campaign finance needs to be—or can be—regulated. It is indeed perfectly possible to leave digital campaigning unregulated. This can be a deliberate choice based on certain normative considerations—such as is the case, to some extent, in the United Kingdom or USA—or because no consensus can be found among a majority of the political forces, sometimes because the use (and advantages) of digital campaigning differ substantially across the parties and/or candidates.

1.1. Banning digital campaigning

When regulators do opt to regulate digital campaigning, the most far-reaching option is to consider a ban. In some countries, social media campaigning has indeed been prohibited in its totality for political actors. This is often a country’s initial response to the emergence of this new communication instrument. For example, when the electoral management body in Chile drafted its first electoral guide on donations and expenses in the lead up to 2016 municipal elections, it included the provision that digital campaigning was forbidden (Jaraquemada 2024). In 2007, Belgian authorities added online advertisements to the list of prohibited campaign instruments during the official campaign period. The rationale behind the decision was that there were too many unknowns about the use and possible impact of this specific campaign tool (Vanden Eynde 2023). In Brazil, paid political promotions on social networks and search engines were banned in 2009 (Grassi 2024).

Yet, in all these cases, the initial ban was revoked at a later stage. The Chilean electoral management body had to quickly retract the ban on digital campaigning following criticism from the public and politicians (Jaraquemada 2024; Zamora 2020). In Belgium, the restriction on online advertisements was removed again in 2013, because regulators felt that this sharp distinction between offline and online advertisements could no longer be justified in the increasingly technological context of society (Vanden Eynde 2023). In Brazil, paid promotions for electoral campaigns on Internet sites and social media were also allowed again in 2017 (Grassi 2024). These practices show how a total ban, or near total ban, is difficult to maintain in practice. Denying political parties or candidates digital options in their campaigns is untenable, especially given the increasing global trend for political campaigns to move online.

1.2. Mainstreaming or innovation: Adapt existing laws or introduce new legislation?

A total ban on online campaigns is becoming increasingly scarce. Most countries are regulating—or considering regulating—the digital aspects of political campaigns. In this respect, regulators have held different perspectives on how digital campaign expenditure should be approached. Some took a ‘mainstreaming’ approach, in which online campaigning is considered a part of established political communication, albeit a new part. In terms of regulation, this means that the rules on online campaigning are incorporated into the mainstream: either the existing laws on political campaign finance have to be revised to include the digital aspects, or they are interpreted in new, innovative ways to enable them to encompass online campaigning as well. In either case, the existing, traditional legislation on campaign finance remains the regulatory core. A second ‘innovative’ approach considers online campaigning as a profoundly new and different form of political communication, which requires a fundamental reformulation of existing laws or else the creation of new rules that specifically target the digital aspects of political campaigns (Nieto-Vazquez 2023; Dommett 2020).

Examples of the mainstreaming approach include Chile, where the Constitution was amended in 2021 with a new provision on communication on social media platforms, designed to clarify the difference between freedom of expression and electoral propaganda. The new provision stated that, although political expressions made on personal or group profiles on social media did not constitute electoral propaganda and were protected by the right to freedom of expression, commissioning digital advertising services would be considered propaganda and would be subject to the rules on campaign finance (Jaraquemada 2024). Similarly, in Kosovo the mandate of the Independent Media Commission, as the oversight body for regulating traditional media during election campaigns, was extended to online campaigns. However, there is a gap in the regulatory framework with regard to digital campaigning, meaning that the commission’s ability to monitor and control online content is jeopardized (Cakolli forthcoming 2025).

In some cases, the existing regulatory framework is not well suited to dealing with online advertising. For example, in Montenegro, the media are defined in the Media Law as subjects engaged in creating and circulating media content that is aimed at an unspecified audience, and exercising editorial oversight or supervision of that content. This definition does not, therefore, cover social media—because of the lack of editorial supervision. Consequently, all rules that regulate the media landscape are not applicable to social media, and the media oversight body has no authority to monitor online platforms. In fact, there is currently no oversight body in Montenegro that monitors social media (Kovačević forthcoming 2025).

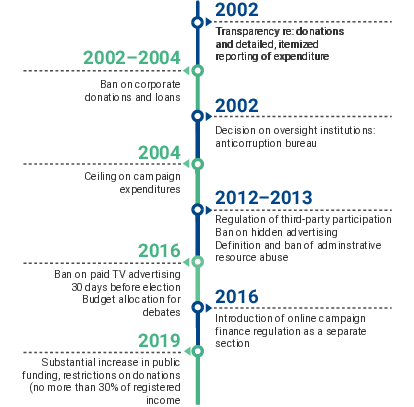

Latvia has taken a combined approach ensuring that the existing regulatory provisions for traditional campaigning apply also to online activities (mainstreaming), and creating new, specific rules for online campaign finance (innovation) (Cigane 2022).

The mainstreaming approach in Latvia shows that, if a legal framework addresses campaign finance in general in a comprehensive and robust way, it can also tackle the challenges linked to the digital aspects of campaigning more easily. This was nicely illustrated by Cigane (2022) in her discussion on how the existing campaign finance rules in Latvia could easily be mainstreamed to include online activities. For example, the general ban on corporate donations could also be extended to online publicity campaigns by companies on behalf of parties or candidates, since this constitutes an in-kind donation. Similarly, since parties must account for and report all campaign expenditure by their candidates, they are incentivized to keep the online campaigns of their candidates in check, as they are counted as part of the total campaign expenses from the party and risk exceeding the legal spending cap. A final example is the regulation of third-party campaigning: the rules in Latvia impose strict limitations on electoral campaigns by third parties, which makes undefined third-party activity online de facto impossible and linked to strict spending limits. (For a comprehensive overview, see Cigane 2022.) Consequently, the emergence of digital campaigning can also be considered a ‘stress test’ of the robustness of the existing regulatory framework on campaign finance.

With regard to the innovative aspect of their approach, Latvia also developed specific regulations related to online campaign activities in 2016. These rules stipulate that: (a) direct contact is required between a political party (or candidate) and a provider of advertising services (which prohibits any intermediation by a PR agency, for example); (b) all companies that offer advertising services, including online advertisement must provide a price overview to the oversight body before the electoral period; (c) companies that do not provide a price overview should be banned from publishing political advertisements during the electoral period; and (d) the sponsor of an online advertisement, must be clearly indicated (Cigane 2022). These measures were mainly aimed at increasing the transparency and accountability of online campaigning.

1.3. Self-regulation or binding rules?

In addition to the mainstreaming and innovative approaches, regulators also hold different perspectives on what the most suitable regulatory strategy would be. While some countries revise or develop binding rules on online campaign finance, others focus primarily on self-regulation—for example, by developing a code of conduct on digital campaigning—or even co-regulation, in which public and private bodies jointly create rules around a common goal (Heinmaa 2023).

In India, for example, there is no specific legislation on social media expenditure by parties and candidates, but the Election Commission of India—in collaboration with online platforms—developed a series of guidelines and a voluntary Code of Conduct to regulate online advertising. Among other things, they focus on the pre-certification of political advertisements, the disclosure of the candidates’ social media accounts when they file their nominations, and the disclosure of social media spending by candidates and parties. Although there have been some positive results arising from the presence of the code, there remain many difficulties in place with regard to effective oversight and enforcing compliance, particularly because of the non-binding nature of the guidelines (Sahoo 2024).

In the run-up to the elections of 2021, the Netherlands also introduced a specific Code of Conduct on online advertisements, to increase transparency, limit profiling and the use of intermediaries, and curb the spread of misinformation and hate speech. Of the 13 main parties and the major online platforms, 11 signed the code and generated relatively positive results (International IDEA 2021).

In Montenegro, parties were requested to sign a Code for Fair and Democratic Campaigns in the run-up to the 2023 parliamentary elections, building on similar initiatives in the past. The signatories committed to provide true and objective information, conduct factchecking and counter illegal influences and combat disinformation. Although the code showed potential, there were several breaches by political parties without severe implications (Kovačević forthcoming 2025).

In Bosnia and Herzegovina, the Press and Online Media Council developed a Press and Online Media Code to improve overall transparency and limit the spread of disinformation and hate speech, but it has generated mixed results (Micanovic forthcoming 2025). Overall, the use of self-regulation is increasingly considered insufficient to fully tackle all the challenges related to online political advertising. But it can be an important first step, especially in countries without a strong tradition of regulating political parties and campaign finance. An example of such a case is the Netherlands, where political advertising has largely been left unregulated and policymakers have traditionally counted on the parties themselves to uphold a culture of electoral integrity. This lack of an extensive regulatory framework made it more difficult to regulate online political advertising. Pending the introduction of new, binding rules, the Dutch Code of Conduct on the Transparency of Online Political Advertisements was negotiated between political parties and online platforms by International IDEA in 2021 as an interim measure (Heinmaa 2023; International IDEA and Dutch Ministry of the Interior and Kingdom Relations 2021).

1.4. Focal point of rules: Parties or platforms?

Similarly, countries can differ concerning which entities are the main focal points of their regulatory efforts. In line with existing frameworks, the rules on digital campaigning can either focus on regulating political actors, or opt to target the digital platforms that enable and host these new forms of political communication—just as traditional media may have been the object of regulation regarding political campaigning. The EU, for example, has developed far-reaching rules on the obligations of online platforms with regard to political advertisements, while its regulatory framework for political parties is more limited.

Yet, despite these different possibilities, many countries have not yet adapted the regulatory framework to incorporate the digitalization of campaign finance. One example is Nigeria, where the existing rules do not include any specific provisions on the role of digitalization and its impact on political and campaign finance. Social media remains to a large extent an unregulated space and has even been labelled a ‘free for all zone’ (Adetula 2024). While there is a specific provision in the Nigerian Constitution banning third parties from campaigning on behalf of a political party or candidate, this is not enforced in practice, including on social media: anyone can fund online advertisements with impunity. There are provisions against fake news and misinformation, but neither of these are enforced (Adetula 2024).

In some countries, the regulatory framework for campaign finance and online advertising can be rather complex, with different applicable legal acts, and responsibilities allocated across a wide variety of actors. For example, in Montenegro, regulation of the media sector alone (without campaign finance) comprises the Media Law, the Electronic Media Law, the Digital Broadcasting Law and the Law on Public Broadcasting Services of Montenegro, which adds to a certain level of regulatory complexity (Kovačević forthcoming 2025). These cases are a good illustration of how many countries still struggle to find a proper regulatory response to the ongoing digitalization of political campaigns.

The most important reason to regulate political campaigns is to create a level playing field among political parties and candidates, in order to ensure not only free but also fair elections (Agrawal, Hamada and Fernández Gibaja 2021). The regulation of digital campaigns with stable and effective rules is a difficult task for many reasons, including the high volume and pace of online communication, the tension with freedom of expression, and the need to enforce transparency and meaningful reporting from online platforms as well as political parties, candidates and third parties. A number of these regulatory aspects are the subject of intense discussion in many countries.

2.1. The definition of digital campaigning

The debate about the regulation of digital campaign finance immediately opens up the discussion on the breadth of the rules required: how should an online advertisement or digital campaign be defined, and which aspects of digital campaigning are—or should be—included in the regulatory framework? Online campaigning can take many forms and is constantly evolving, meaning that definitions are often quickly outdated and fail to capture new developments in the digital sphere.

The first important point to consider is the exact definition of an online political advertisement. Regulating political campaigns must be weighed against the importance of freedom of expression and not all online advertisements of a political nature fall within the scope of regulatory regimes. Civil society organizations (CSOs), such as Greenpeace or the World Wildlife Fund, might also launch advertisements online that are political in nature but these should not necessarily be covered by the regulatory framework for parties or candidates. At the same time, a definition that is too narrow risks creating loopholes that can be exploited by political actors to circumvent the rules.

Some regulators focus on a specific definition for online advertisements, while others include the digital aspects of advertising within a broader definition of all political or electoral communication. An example of the former is Mexico, where specially paid digital advertisements are defined as ‘insertions, e-banners, tweets, published messages, social media accounts, websites and other similar paid items whose purpose is to promote a campaign, a political party or a candidate’ (Nieto-Vazquez 2023: 4). This is quite a broad, encompassing definition, but does not include, for example, paid advertisements in favour of or against a specific policy issue (although this could be interpreted as a ‘campaign’). In the USA, the definition of a political advertisement is the subject of much discussion, since it includes advertisements ‘placed’ for a fee but not ‘promoted’ for a fee, which might mean that many advertisements fall outside of the scope of the rules (Venslauskas 2024: 9).

Other countries apply a definition that captures all electoral communication. In Chile, for example, electoral propaganda is defined as ‘any event or public demonstration and radio advertising, written, in images, in audiovisual media, through social networks, when there is a contract and a respective payment, or other analogous means, provided that it promotes one or more persons or political parties constituted or in formation, for electoral purposes’ (Chile 2016: article 30). This is again a rather broad definition, and means that any paid services on social media to promote a candidate or political party are considered political propaganda, and thus fall under the corresponding rules and transparency requirements. Similarly, a person, organization or company that is hired to develop or implement an online advertising strategy, or cases of telephone and email campaigning, also fall within the definition (Jaraquemada 2024).

However, even such broad definitions demonstrate definitional challenges: the Chilean law distinguishes between promotional activities and those messages ‘disseminating ideas or information on political acts’, which is considered a form of freedom of expression (Chile 2016). The instruction guides of the oversight body indeed also state that only ‘promotional advertisements’ that involve the commission of paid advertising services are considered electoral propaganda, and not the non-paid communication from the personal profiles of candidates and parties (SERVEL 2017, 2021). There nevertheless remains a legal grey area, and it is up to the oversight body to determine the difference and interpret the messages on a case-by-case basis. For example, when a social media influencer uses their personal account to promote a candidate or a party without specifically purchasing an advertisement, this can be considered either as a form of freedom of expression, or as ideas or information on political acts, or as an in-kind donation of services (comparable to the free performance of an artist during an electoral rally) (Jaraquemada 2024).

It is important to note that laws are not always limited to regulating paid political communication, and that the rules can be applicable only to political parties (or electoral coalitions) and candidates, or have a much wider scope. This is often related to the breadth of the definition of freedom of speech. In Mexico, for example, online political messages are divided into two categories: those messages without any other interest other than sharing views, and those published with the specific purpose of obtaining votes. In order to assess whether political communication falls within the scope of the rules, the regulatory authorities have adopted a set of criteria, such as the cost of the production involved, the timing of the message and the taxpayer status of the source of the message (Nieto-Vazquez 2023). Conversely, in Brazil, ‘organic’ electoral advertising—the publication of content without paid promotion—on social media is also regulated in the rules on electoral finance (Grassi 2024).

This touches upon the second important element to consider when defining digital campaigning: what should be included in the broader phenomenon of online campaign expenditure, and—consequently—become the object of certain obligations and restrictions. Rules on political campaigning differ substantially in terms of their range of regulated activities. India has a rather broad definition of social media expenditure that parties and candidates need to report. It includes payments for advertisements made to online platforms, operational expenses related to the development of campaign content or the maintenance of social media accounts, and salaries/wages paid to employees or professionals who undertake the tasks of maintaining these accounts (Sahoo 2024).

A non-exhaustive list of aspects of digital campaigning can include:

- the development and publication of websites and (micro)blogs (including domain specification);

- the creation of online content (copywriting, audiovisual material);

- political advertisements on websites and social media platforms;

- background research (surveys, big data analysis and so on) for profiling in preparation of (targeted) online campaigning;

- salaries (or fees) for data specialists or legal experts (to verify compliance with existing rules on the collection and use of data and other aspects of digital campaigning);

- salaries (or fees) for communication and social media staff, or influencers;

- fees for volunteers to disseminate and amplify political messages; and

- large-scale communication campaigns through email or instant messaging.

2.2. Different or similar rules for digital and physical campaigns

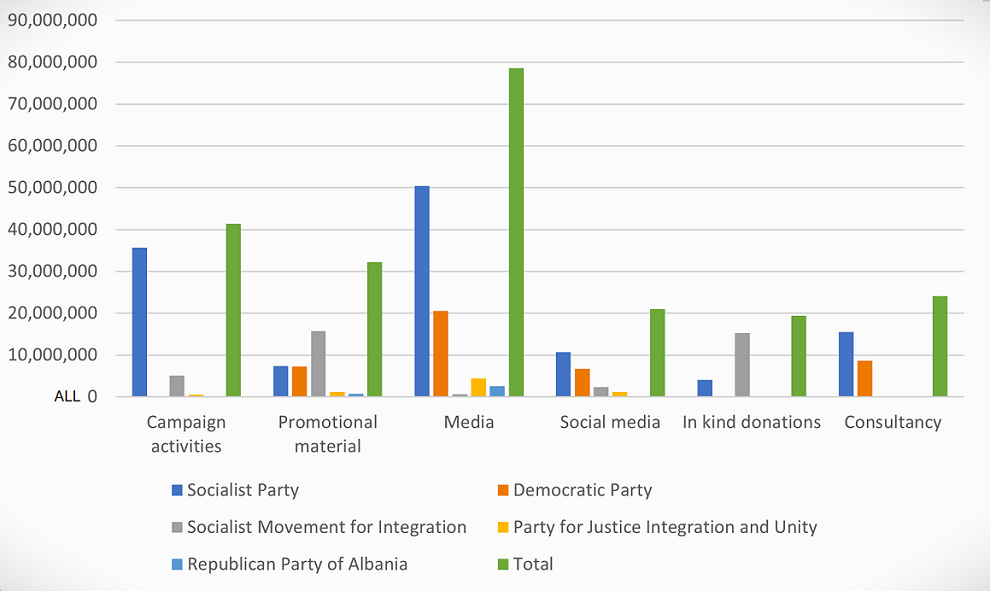

An important consideration is to what extent digital and physical campaigns have to be subject to the same—or at least similar—restrictions. This is linked to broader discussions about whether the digital aspects of political campaigns are best mainstreamed into the existing regulatory framework or a separate body of rules needs to be developed, and whether digital advertisements or campaigns should be included within a broader definition of political communication or not. Yet, in many countries, there are specific debates about the limitations that should be imposed on online campaigning, and whether these should be different from those on more traditional forms of campaigning. In Albania, clear limits on campaign expenditure in traditional media advertising exist, but these limits do not apply to social media advertising (Power 2024).

In Belgium, there has been an extensive debate on the regulatory limitations of social media campaigns. Since 1989, political campaigns have been closely regulated: there is a strict spending cap, and advertisements on both radio and television are banned, as well as the use of commercial billboards or commercial phone campaigns. In 2007, it was decided to ban online advertisements as well during the official campaign period (which at the time started three months before the election date), but not audiovisual content on the websites of parties and candidates (even when developed by an external media company). In practice, this meant that the digital toolbox for parties and candidates was limited to their own websites and emailing. In 2013, however, the ban on the use of online advertisements was removed (Vanden Eynde 2023).

However, there are ongoing discussions about curtailing digital campaigning again. In 2020, a new proposal was submitted to ban all commercial advertisements. The proponents argued that there is no valid justification to allow online advertisements, while political commercials in cinemas, on commercial billboards, and on television and radio are prohibited during the official electoral period. Another proposal aims to limit the share of campaign expenditure used for online targeted messages to 50 per cent of the total campaign budget of a party or candidate. The proposal is motivated by the need to protect personal data (since such targeted campaigns rely heavily on the collection of citizens’ personal data) and to limit the spread of fake news and disinformation (Vanden Eynde 2023).

Another example is the USA, where substantial differences existed concerning the transparency of online advertisements compared with traditional television and radio advertising. The latter has in recent decades been bound by strict and detailed rules, which stipulate that, among other things, clearly written, visible and understandable disclaimers are linked to each advertisement to disclose who paid for it and whether it was authorized by the candidate. Such disclaimers were historically absent from the regulatory framework for digital campaigning: it was not until 2022 that the Federal Election Commission introduced a similar rule on disclosure requirements for online advertisements (Venslauskas 2024). These examples show that a differentiated approach—in which online and physical or more traditional advertisements are regulated differently—potentially creates a tension for regulators, or can at least be the subject of intense debate.

2.3. Official campaign period and online advertisements

In several countries, a specific electoral campaign period is defined, during which time certain campaign activities are either permitted or, alternatively, subject to restrictions and limitations. Digital campaigning offers new challenges concerning the demarcation and enforcement of such a specific electoral campaign period, even if this is included in broader definitions of political communication and/or campaign expenditure.

A good example is Montenegro, which applies the concept of an ‘electoral silence’: a period of 24 hours before election day during which electoral propaganda via rallies and traditional media is prohibited. However, this provision is not applicable to campaign activities on social media (Kovačević forthcoming 2025). This is also the case in India, where the silence period is not applicable to online advertisements. During the 2022 elections in Brazil, there was a prohibited period for campaigning, but a difference was made between physical and online campaigning. Paid promotions—including on the Internet—were banned for two days before election day, and the promotion of printed materials was prohibited for one day before the election. Yet, what was not clear was to what extent organic campaigning—including non-paid advertising—on social media platforms was permitted during these silence periods (Grassi 2024).

Often parties and candidates try to work around the limitations of having a specific electoral period, and online campaigning can provide possibilities for doing this. In Nigeria, there are quite extensive rules on campaign expenditure (such as for advertisements, campaign materials and campaign rallies), but these rules are not in force outside the fixed electoral periods. There are clear indications that political advertisements on social media were widely used before the start of the official campaign period in the run-up to the 2023 presidential elections, as a way of circumventing the expenditure ceilings (Adetula 2024; Alayande 2022). Kosovo is also characterized by similar evidence of frontloading online campaign expenses so as to stay below the expenditure threshold linked to the official electoral period (Cakolli forthcoming 2025). In Bosnia and Herzegovina, the ban on paid advertising before the official electoral period is frequently circumvented by parties and candidates, especially through social media campaigning (Micanovic forthcoming 2025).

Another question is about the extent to which the costs of developing advertising content should be included in the total campaign cost if the advertisements were created before but published during the regulated electoral period. This is, of course, particularly important where electoral spending caps are in place.

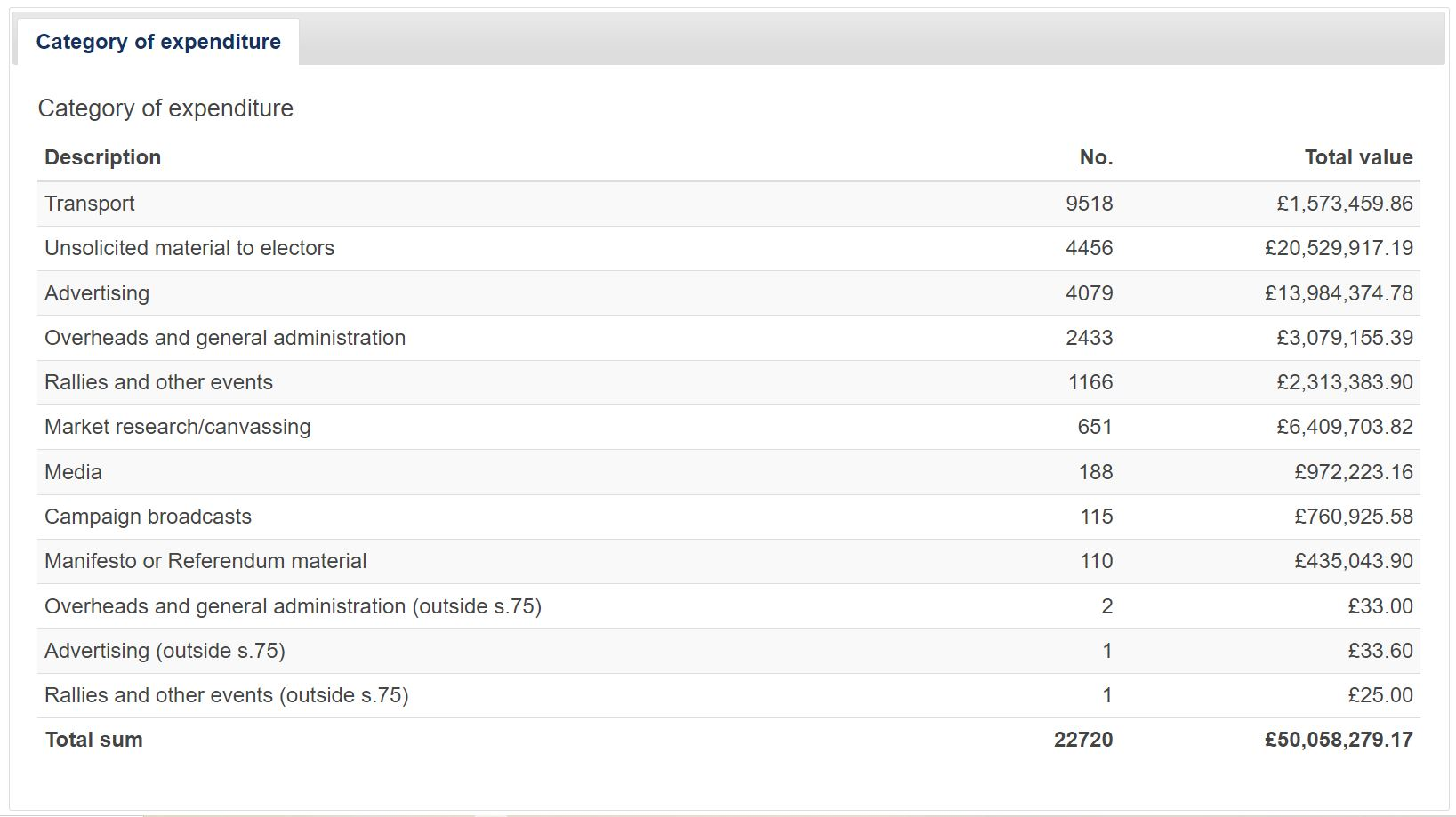

Belgium also has an official campaign period—four months before the elections—with a clear expenditure ceiling: political parties may not spend more than EUR 1 million on their electoral campaigns (and different expenditure caps apply to individual candidates depending on their position on the electoral list). However, the main effect of this regulation has been an enormous increase in expenses on political advertisements before the official campaign period (Maddens et al. 2024). By way of a response, new proposals are being discussed in Belgium to introduce an annual spending cap of EUR 1 million per political party on all political dissemination and advertisements (both offline and online). According to the proponents, this would limit the enormous amounts of public money that go to social media platforms—Belgian parties are predominantly financed through state subsidies—and would create a more level playing field between parties with and without substantial financial resources (Vanden Eynde 2023).

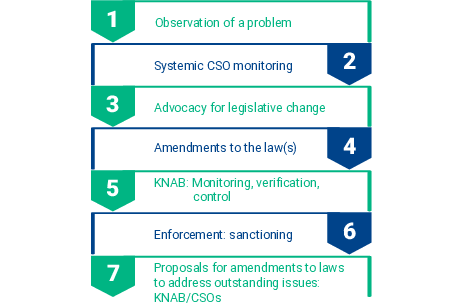

Monitoring campaign finance has always been a challenging task, and the expansion of digital campaign tools has only complicated it. In terms of the definition of oversight, it is useful to differentiate between primary and secondary oversight. Primary oversight entails the monitoring activities of the bodies that are assigned a specific formal role in the regulatory framework, such as audit companies or election monitoring bodies. Secondary oversight is related to the activities of CSOs, activists, journalists or academics, which follow and scrutinize the campaign activities of political actors.

3.1. Role of oversight agencies

Oversight agencies are heavily dependent on the responsibilities and boundaries that are set by the general regulatory framework on campaign finance. In most European countries, no authorities have a clear formal oversight mandate for online political advertising (Heinmaa 2023). Regulators have different options on how to deal with the digitalization of campaign finance. Either they take a more conservative position and act as ‘constructionists’ that work from what is written and (only) do what is explicitly stipulated in the rules, or they take a more ‘activist’ position and treat the existing electoral and campaign finance rules as a living document that can be interpreted and adjusted to changing political circumstances (Power 2024). Even if a clear regulatory framework is not present, this does not always prevent an oversight body from acting. For example, in Brazil the main oversight entity—the Superior Electoral Court—regulates elections and electoral expenses mostly through resolutions, in the absence of any specific legislative acts (Grassi 2024). When regulatory frameworks are adapted to incorporate digital campaigning, new powers are often entrusted to existing oversight entities. For example, in Mexico the Constitution was amended in 2007, which ushered in a new era of political communication, giving the electoral authorities the power to investigate and sanction organizations and individuals both inside and outside politics (Nieto-Vazquez 2023).

One important question is whether oversight agencies should be given the power to proactively monitor political messages before they are published. For example, in Mexico, the constitutional reform of 2007 granted the National Electoral Institute the authority to review and approve campaign messages before they are broadcast, on both traditional and online media: parties and candidates must submit a proposal for any paid audiovisual advertisement (Nieto-Vazquez 2023).

The proper monitoring and oversight of online campaign finance requires specialist knowledge and expertise, such as database management, data compilation and analysis, social media communication analysis, cybersecurity and data security, and financial transaction technology. This often means that the oversight agencies need to develop or hire new expertise to complement their existing capabilities. The Irish Election Commission can—in addition to its own investigation of online advertisements—also engage external assistance and expertise (Heinmaa 2023). Similarly, in several countries, oversight agencies employ observers in the run-up to an election to help in the monitoring of compliance with campaign finance rules. However, while observers are well established for physical campaign activities in some countries, there are fewer observers in place for digital aspects of campaigning. Properly monitoring online campaigns also requires specific skills, which can mean additional training is needed. For example, in Nigeria the Independent National Electoral Commission deployed observers in the run-up to the 2023 general elections. While they were relatively effective at tracking expenditure on large billboards, posters and advertisements in traditional media, they were less successful in monitoring the online advertisements of parties and candidates (Adetula 2024).

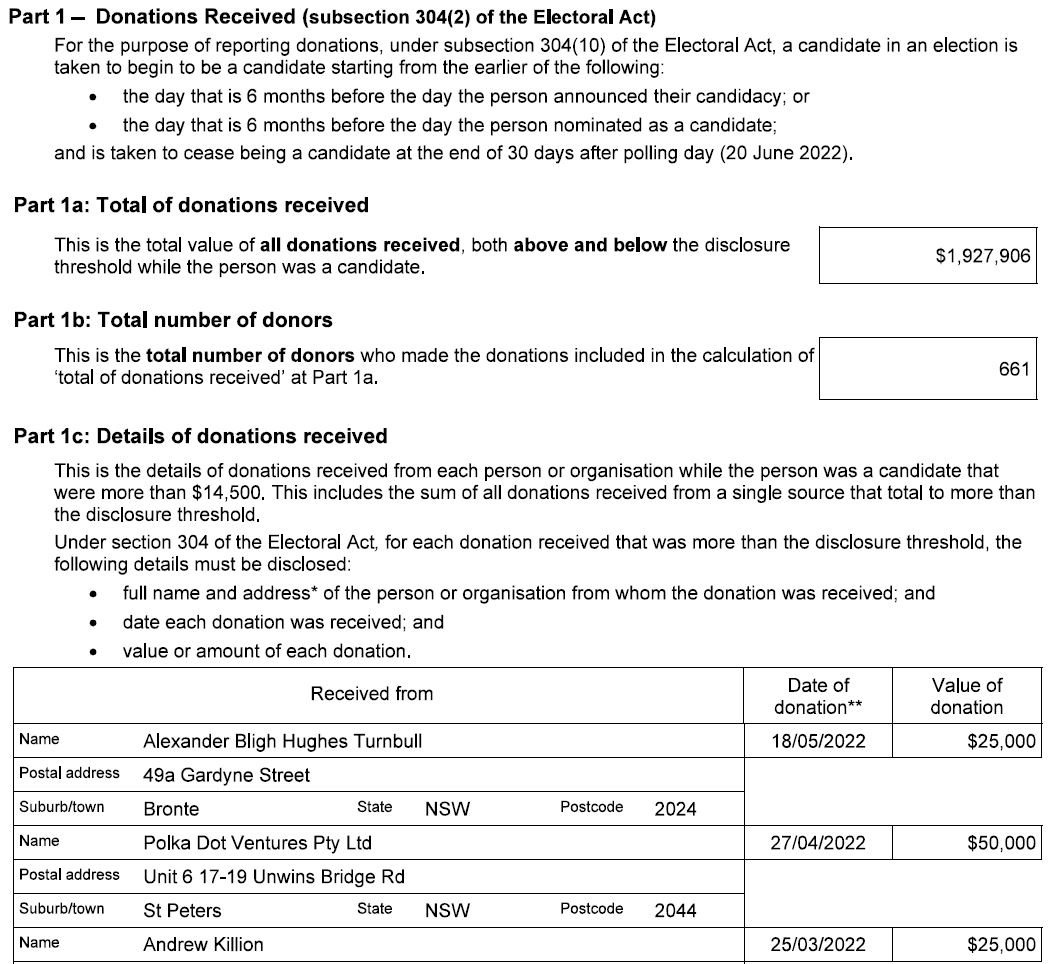

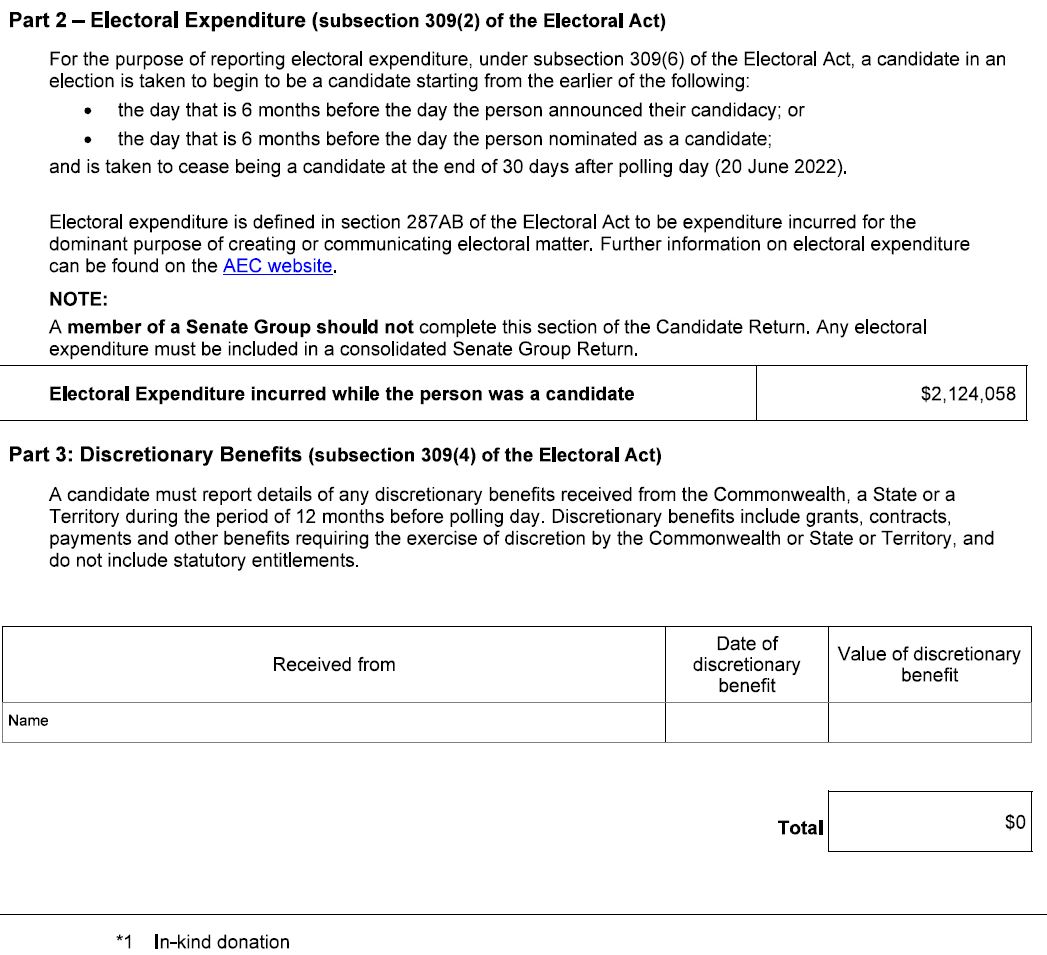

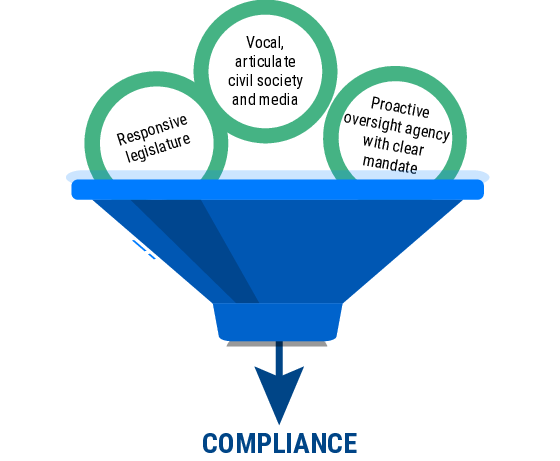

3.2. Prerequisites for successful oversight

A first important condition for successful oversight is the availability and quality of information on the actual digital expenditure incurred by political parties and candidates, in particular the level of detail (or granularity) of that information. In this respect, the difference between the information available for primary scrutiny and that for secondary scrutiny is pertinent. While CSOs or journalists depend on data that is made publicly available (from the parties and candidates themselves as well as the official bodies or even online platforms), official oversight entities generally have more possibilities for accessing information. Yet, the level of detail and the timing of the information on expenditure often depends on the provisions included in the regulatory framework.

A couple of examples can illustrate this point. During the 2022 elections in Bosnia and Herzegovina, the oversight body obliged parties and candidates for the first time to include in their campaign expenditure reports a separate line covering online spending. This increased transparency, although to a limited degree, but the lack of detail means it is impossible to determine exactly how, and on what platforms, the money was spent (Micanovic forthcoming 2025). In the USA, there are no regulations that require sponsors of online advertisements to disclose their expenses and their donors (Venslauskas 2024), which makes comprehensive secondary oversight difficult, if not impossible. In many countries, the categorization used in the financial reports is too vague to allow for a detailed assessment of online communication expenditure (even for the official oversight bodies). In Nigeria, there is only limited itemized detail in the financial reports of the parties and candidates, which hampers proper oversight (Adetula 2024). Similarly, the absence of a dedicated category for online campaign expenditure on the financial reporting forms in Kosovo substantially hampers proper oversight. It can lead parties to categorize these expenses under different headings and therefore makes it difficult to compare and, more importantly, to enforce the legal threshold of EUR 5,000. ‘In addition, since all expenditure and donations need to be done from a dedicated party bank account, candidates are consequently not allowed to receive donations directly, or make personal campaign expenses. However, the lack of financial reporting from these actors makes proper oversight over these actors more difficult’ (Cakolli forthcoming 2025). In Montenegro, parties and candidates are required to provide comprehensive reports on their campaign expenses to the oversight body, but it is very difficult to know the exact cost of digital campaigns. The reports indicate the overall campaign costs, but many parties enlist media companies to conduct online campaigns on their behalf, and the exact expenses of these advertisements are not indicated (Kovačević forthcoming 2025).

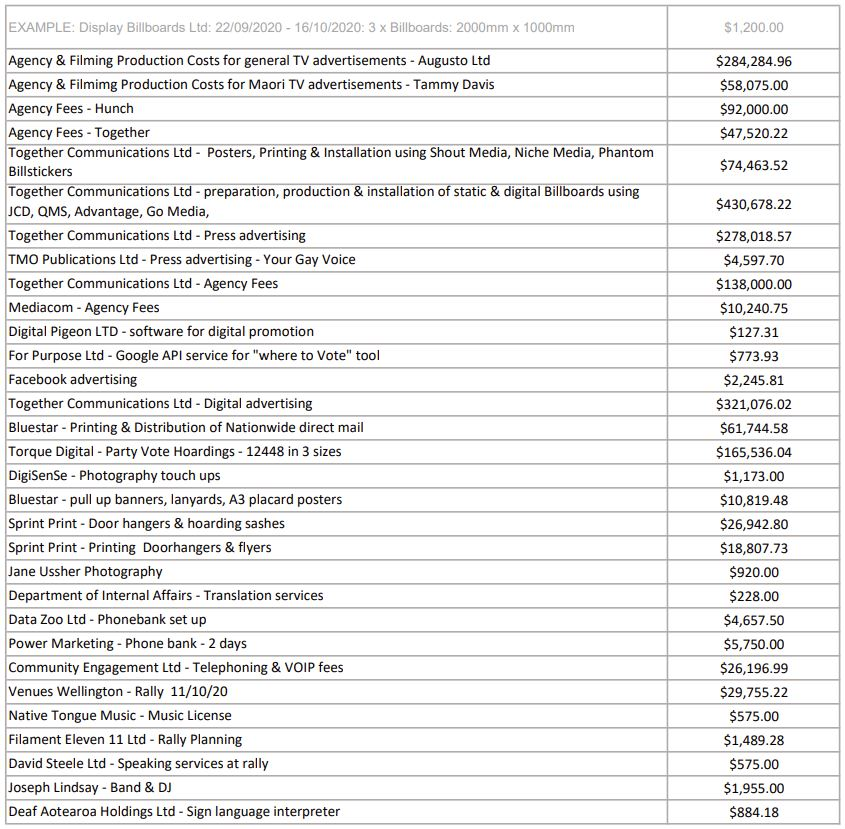

The Indian oversight body also adapted the template for the financial accounts in 2022 to include a new column specifically dedicated to expenditure on digital campaigning (Sahoo 2024). Similarly, in Chile the electoral management body—the Electoral Service—has developed a specific form for the reporting of all expenses specifically related to digital campaigns. This includes, among other things, information on the platform that is used, the contract period and the amounts involved. However, not all political parties and candidates used the form to report their digital expenses, and their financial reports lacked details on the specifics of their digital campaign expenditure (Jaraquemada 2024). In an attempt to tackle this issue, new rules now oblige online platforms to publish the fees they charge for all advertisements (including political advertisements), and to report on the advertisements that are sponsored by political parties and candidates. These new provisions are also enforced, as the 2023 sanction of Google by the Electoral Service for non-compliance can testify.1 Another example is Latvia, where the mainstreaming approach has resulted in all aspects of online campaigning being included in the itemized and detailed political finance reports (Cigane 2022).

As important as the level of detail, in facilitating the task of oversight, is the ability to check the information provided by the parties and candidates against the original documents and other data. In Mexico, parties and candidates must keep all contracts and invoices for advertisements published on the Internet (Nieto-Vazquez 2023). In India, the oversight body expects all candidates and political parties to keep information on all aspects of online campaign spending, such as direct expenditure on the publication of social media advertisements, payments to Internet companies and websites, operational expenditure on creative content development, and salaries paid to professionals/staff (Sahoo 2024). In this respect, the use of an electoral reporting system facilitates the monitoring process (Wolfs 2024). In Brazil, parties and candidates must use the electronic reporting system to notify the oversight body of the amounts spent on digital campaigning, including a description of the expenses, information on the service provider and a copy of the invoice or receipt (Grassi 2024).

Especially when monitoring online campaigns, the ability to compare the information provided by the parties and candidates with data originating from the social media platforms themselves is incredibly useful. In Montenegro, there were many cases of contestants initiating social media campaigns before they had established a dedicated campaign bank account, which complicated proper oversight of campaign expenditure. In addition, there is only limited access to data from the online platforms, which makes it difficult to compare this with the financial reports of the parties and candidates to assess their accuracy (Kovačević forthcoming 2025). Yet when data is provided by the platforms, but it is not comprehensive, this creates new oversight challenges. For example, the digital spending data of the Chilean parties and candidates did not match the data published by Meta—the most widely used platform, Facebook—which might indicate that parties and candidates also reported expenditure on other social media platforms (for which no data sources were available) (Jaraquemada 2024), or could mean they made errors in their reports, whether accidental or intentional.

A second important condition for successful oversight is that the monitoring bodies are given the instruments to duly fulfil their task. Indeed, a comprehensive regulatory framework is not sufficient to ensure fair political competition. This also requires a strong oversight entity that has the competences, resources and willingness to enforce compliance with the rules.

There are many examples of politicians that have breached the rules but did not encounter any repercussions. In the run-up to the 2022 elections in Brazil, a non-governmental organization concluded that 171 of the 375 social media accounts (almost half at 46 per cent) did not respect the prohibited period for paid electoral campaigning, and 306 of the 375 accounts (82 per cent) did not comply with the ban on organic campaigning in the last days before the elections (Grassi 2024). Similarly, 20 per cent of the first-round candidates did not declare their expenses, mainly because the current rules relieve non-elected candidates from reporting obligations (Grassi 2024).

This has also been the case in Chile, where rules on the permitted periods for electoral campaigning were not respected on social media in the context of the 2021 elections. The oversight body experienced substantial challenges to enforcing compliance (Jaraquemada 2024). Similarly, while the Nigerian Constitution bans anyone other than political parties and candidates from political campaigning (on behalf of parties and/or candidates), this is not enforced, especially on social media. In practice, anyone can place paid advertisement on social media in support of or opposing a political party or candidate. When funded by third parties, this expenditure often remains undisclosed (Adetula 2024). In addition, Nigerian parties and candidates often neglect to provide detailed information on campaign expenditure (although this is legally required), but there has never been a sanction for political finance infringements in the country. For example, after the 2023 general elections, no financial report on the campaign expenses of political parties had been submitted to the oversight body within the required timeframe, and when they were later submitted, important information (especially on the expenditure of individual candidates) was missing (Adetula 2024).

3.3. Role of civil society and the media

Civil society has always had an important function in monitoring elections, as CSOs conduct the core of the secondary oversight that complements the work of the official bodies. The shift of campaign activities to the digital realm has only increased the importance of their role. During the 2022 elections in Brazil, the Getulio Vargas Foundation think tank monitored the activities of political social media accounts and found several breaches of the campaign finance rules (Grassi 2024).

In countries where there is already limited involvement in monitoring campaign finance by CSOs, extending their work to the digital aspects of political campaigns can be even more challenging. In Nigeria, the engagement of CSOs in monitoring party and campaign finance is rather marginal and uncoordinated, mainly because of limited resources and organizational capacity, and because of limited collaboration from the political actors themselves (who refuse to share financial information) (Adetula 2024). Albania has a vibrant civil society that is active in the field of monitoring campaign expenditure, but most of these organizations are donor-funded, which makes them fragile and vulnerable to declining funding from international donors, making their work unsustainable and subject to funding availability (Power 2024).

Even in countries with strong oversight bodies, CSOs fulfil an important function. The Corruption Prevention and Combating Bureau in Latvia, for example, is one of the strongest oversight entities in Europe (and the world), but still relies on citizens to supply the majority of the evidence it evaluates on possible campaign finance violations, including in the online space. This high degree of involvement from civil society can be explained by the serious level of attention paid to campaign finance in the media and society in general, and by the user-friendly reporting procedures. The latter were developed as a direct response to possible foreign election interference online in the run-up to the 2018 elections, following a call for action from civil society (Cigane 2022). This decentralized approach, counting on the collaboration of citizens and CSOs, can be particularly useful in an online environment that is characterized by the microtargeting of small groups in digital political advertisements that might escape the attention of the official entities. For this reason, the Election Commission of India made specific investments to strengthen the involvement of CSOs and even ordinary citizens in its monitoring process. It developed an application—the ‘cVIGIL app’—which allows citizens to report potential instances of misuse of campaign finance. Despite the potential of such an application, the limited user-friendliness and minimal response from the oversight body limit its effectiveness (Sahoo 2024).

Online platforms play a central role in digital campaigning, and their actions can hamper or strengthen oversight, especially in countries where dedicated legislation is lacking. The various online platforms have had different approaches towards political advertising. Several—such as LinkedIn, Telegram and TikTok—prohibit all forms of political advertising: sharing political beliefs and expressions is only allowed as organic content. Following several controversies regarding political campaigning, X—previously Twitter—banned political advertisements, but announced it would lift the ban again in the run-up to the 2024 US elections (Venslauskas 2024).

Other platforms have taken a more pragmatic approach, especially because political advertisements constitute an important source of revenue. Obtaining cooperation from social media platforms can be challenging, especially in smaller countries, and sometimes requires substantial political pressure. For example, Latvia undertook several public diplomacy activities—including the country’s president making a visit to the headquarters of Facebook in California—in an attempt to gain the collaboration of the platform in the run-up to its elections in 2018. Yet, this did mean that the country was able to obtain all the requested information regarding campaign spending on the Facebook platform, and a comparison between the data from the platform and the financial reports from the political parties showed a high level of similarity. In addition, from 2019 onwards, the platform only allowed political advertisements from users residing in the country where the elections were held (in an attempt to curb possible foreign interference) (Cigane 2022). An additional regulatory challenge is that these platforms might offer services in a country without being legally established there, which may result in legal challenges and disputes regarding whether a country’s electoral body has any jurisdiction or control over them.

The first important consideration is the level of transparency that online platforms can provide on the sponsors of political advertisements. Several platforms have started proactively providing more transparency on political advertising, often through a voluntary code of ethics. In the run-up to the 2019 European elections, the main online platforms developed a Code of Practice in collaboration with the European Commission to provide more transparency on political advertising and to tackle disinformation. However, the results were, for the most part, disappointing (Wolfs 2024).

Also in 2019, the major social media platforms that were active in India—Twitter, Facebook, Google, ShareChat, TikTok and WhatsApp—drafted a similar code in collaboration with the Internet and Mobile Association of India. The Voluntary Code of Ethics contained four key commitments: (a) implement education and awareness campaigns, and establish a fast-track grievance redress channel to take action on objectionable posts; (b) take action within three hours of reported violations of the mandatory 48-hour period of no-campaigning and advertising silence before voting; (c) the pre-certification of all political advertisements published on their platforms by the government’s media certification and monitoring committees; and (d) report paid political advertisements and label them accordingly (Mehta 2019; Sahoo 2024). However, the code only seems to have had a limited effect, as there have been widespread instances of violations of the code and only limited follow-up by the oversight bodies. For example, in the context of the 2019 elections, 510 code violations were reported but only 75 were analysed by the Election Commission and no penalties were imposed (Sahoo 2024).

An important challenge in this respect is that the platforms do not always apply the same definition of political advertising, or they use one that deviates from the formal legal definition. This has important implications for the number and type of advertisements that are included in the repositories of the platforms, and thus also the possibilities for oversight entities and other actors to monitor social media expenditure.

The definition of political advertising used by Meta is anything that: (a) is made by, on behalf of or about a candidate for public office, a political figure, a political party or a political action committee or advocates for the outcome of an election to public office; or (b) is about any election, referendum or ballot initiative, including ‘get out the vote’ or election information campaigns; or (c) is about any social issue in any place where the advertisement is being run (Jaraquemada 2024). This last condition in particular substantially widens the scope of the definition and is broader than the legal definitions used in most countries. The broad definition Meta uses also makes it a lot more difficult to differentiate between ‘political’ and ‘electoral’ expenditure. This is complicated further by the fact that it is difficult to delineate specific time periods in the Meta advertising archive for collecting historical expenditure data. In Canada, the electoral rules differentiate between two types of advertisements that online platforms must include in their online registries: ‘partisan ads’ focused on promoting or opposing a party or candidate; and ‘electoral ads’ that take a specific position on any issues during a federal electoral campaign (Power 2024).

Google has a different policy for political advertising depending on the region. In some regions, advertisements may only be published if the advertiser is verified by the platform. In regions or countries where electoral advertising requires verification, the advertisement must contain information on the sponsor: an advertiser identification label ‘is generated from the data provided during the verification process and is automatically included in most ad formats’ (Jaraquemada 2024

Without detailed information from the platforms themselves, it is often difficult—and in many cases even impossible—to track the donors of online advertisements, which further complicates verification procedures. This can then have an impact on assessing whether parties and candidates have complied with any spending limits that might apply. Data from online advertisement repositories can indeed provide an important source of comparison with the information provided by the parties and candidates themselves in their financial reports and may lead to further investigation in the case of substantial inconsistencies. This is why several countries have taken binding regulatory action to impose transparency requirements. For example, in Brazil all online electoral advertisements must be identifiable by the candidate’s corporate taxpayer number as well as information on the party or electoral coalition. In the USA, transparency disclaimers on the sponsor were absent from online advertisements for a long time, while being mandatory for advertisements on traditional media. The Federal Election Commission introduced new rules, taking effect in 2023, requiring each online communication to have a disclaimer which ‘must be presented in a clear and conspicuous manner to give the reader, observer, or listener adequate notice of the identity of the person that paid for the communication’ (Federal Election Commission n.d.). More transparency measures have been proposed—such as a ban on advertisements funded by foreign nationals and the mandatory creation of databases of online advertisements—but these have not (yet) been approved by the US Congress (Venslauskas 2024).

Yet, even when online platforms provide transparency on advertising costs, the information is often incomplete or inaccurate. The repository for Meta includes banded estimates of expenditure only, and because of the nature of online advertising, including its virality, the use of influencers and the relation between organic and paid content, the costs of different advertisements can vary substantially, with prices rising and falling (Dommett and Power 2019; Nadler, Crain and Donovan 2018; Power 2024).

The EU has also introduced far-reaching legislation on transparency. It stipulates that advertisements on online platforms should be clearly labelled as such to allow users to differentiate them from other content. In addition, an advertisement must identify both the natural or legal person that paid for it and the natural or legal person on whose behalf it is presented. Applied to political advertising, this means that both the sponsor of a political advertisement and the party or candidate that it is promoting must be made clear. Consequently, these provisions also entail de facto transparency in online campaigning by third parties (Wolfs 2024). From 2025 onwards, every political advertisement should be linked to a ‘transparency notice’, which has to include: the identity and contact details of the sponsor; the period of publication; the amounts spent and the source of funds; and the election or referendum to which the advertisement is related. In addition, for online advertisements, it must be made clear whether an advertisement is specifically targeted, and if so what criteria have been used for that targeting, and whether and to what extent amplification techniques were used to boost the advertisement’s reach. Platforms will not be allowed to publish the advertisement if it does not include this information (Wolfs 2024).

The EU approach seems to be heavily inspired by Ireland’s Electoral Reform Act of 2022, which also obliges the use of a digital imprint for online political advertising. The text ‘political advert’ should be clearly displayed, and a transparency notice should be accessible, which should include details on the buyer of the advertisements, and on the use of microtargeting, the total amount paid for the advertisement, the estimated size of the audience, the number of views and a link to the online advertisement repository of the platform. In addition, the act also obliges platforms to verify the identity of the sponsors of online political advertisements (Power 2024).

Discussion on the role of online platforms often goes further than providing mere transparency; some regulators also expect a level of intervention by the platforms, especially in the context of reducing possible fake news. However, the debate on countering fake news and disinformation touches upon the important principle of freedom of speech. Removing content—in this case, political content—from a social media platform must always be weighed against the freedom of expression of citizens. That is the reason why in many countries only a judicial authority can impose the removal of online content. But the slow pace of a judicial process often contrasts with the volatility and speed of circulation of possible fake news on online platforms. Regulators are trying to adapt to this new environment. For example, in Brazil, the rules were changed in 2022 to grant judicial authorities more possibilities in tackling disinformation. Previously, a separate lawsuit had to be filed for each link that was suspected of containing fake news, even if different links had the same exact content. The new rules allowed judicial authorities to target any existing or future online links that contained the same content (Grassi 2024).

The digitalization of political campaigning has created new challenges for regulators, and further complicated existing challenges.

5.1. Third-party campaigning and in-kind contributions

Third-party campaigning has long been a sensitive issue for regulators, but the new forms of digital communication have only amplified the challenge. The term ‘third party’ refers to stakeholders, other than the political parties and candidates themselves, who engage in electoral campaigning. Some of the most well-known third parties are the political action committees (PACs and Super PACs) in the USA—organizations that pool donations and contributions with the aim of funding campaigns for or against certain candidates or policy issues.

Third parties can be influential actors in an electoral competition. The USA is a typical example here, but research on the 2019 elections in India also indicates that most expenditure on digital platforms was not made by the political parties and candidates but by their sympathizers or affiliated groups. Since political advertisements by parties and candidates need to be pre-certified, third-party campaigning can be used to circumvent this requirement. In addition, the parties and candidates often also escape liability for the content of these third-party posts because of weak regulatory provisions (Mehta 2019; Sahoo 2024). In Brazil, companies are no longer allowed to contribute to political campaigns, so instead they hire people to campaign on behalf of the parties or candidates or pay for online campaigns on Meta platforms or TikTok. For example, there was evidence that entrepreneurs had spent millions in mass messaging services in favour of Bolsonaro during the 2018 presidential campaign (Campos Mello 2018). This constituted an illegal strategy, since Brazilian law prohibits companies from donating to political campaigns (Grassi 2024), but the direct nature of such campaigning could have been designed to circumvent the restrictions on third-party campaigning.

Third-party involvement also appears to be on the rise in Kosovo, where for example one-third of campaign advertisements on Facebook and Instagram during the 2021 local elections were attributed to third parties. Interestingly, these accounts were mainly focused on negative campaigning and attacking certain candidates instead of placing advertisements in support of a specific party or candidate(s) (Cakolli forthcoming 2025). In India, the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) deployed more than 1.2 million ‘volunteers’ (actually paid by the party) on social media, which in some cases operated as ‘troll armies’ to dominate the narrative online and push the party’s political platform (Sahoo 2024; Sen, Naumann and Murali 2019). In general, third parties are often found to be spending much more than official political parties and candidates on online advertising globally. Their substantial role in elections thus highlights the importance of regulating third-party activities.

In some countries, an important difference is made between paid and unpaid advertisements from third parties. If they launch paid advertisements, this is often included within the scope of rules on campaign expenditure. In Belgium and Mexico, for example, any campaign expenses from third parties are added to the total expenditure of the political parties or candidates being promoted. Of course, such a measure only has an impact when expenditure limits are in place. In 2018, the Canada Elections Act was revised with the specific aim of establishing a spending ceiling for third parties, banning the use of foreign funding by third parties and increasing the transparency of their participation in the elections (Agrawal, Hamada and Fernández Gibaja 2021).

The Chilean definition of electoral propaganda is sufficiently broad to also include third-party campaigning. It is defined as ‘any public event or demonstration, or radio, written, visual, audiovisual or other similar media advertising, if it promotes one or more persons or political parties, for electoral purposes’ (Chile 2016), which means that regardless of who pays for online political advertising, it falls within the rules when a candidate or party is promoted in the context of elections. Moreover, even if a person offers their services for free—for example, for the development or implementation of an online advertising strategy—these must be declared and valued as campaign contributions in line with the respective rules (Jaraquemada 2024). However, advertising and propaganda is increasingly being seen from campaigning movements, grassroots or social organizations that campaign specifically in favour of, or against, issues that are closely related to the political platforms of parties or candidates. While this could fall within the general right of freedom of expression, research by investigative journalists has shown how, in some cases, these organizations were used to issue electoral propaganda. Yet such campaigns have largely escaped monitoring by the oversight body (Jaraquemada 2024).

In Nigeria, third-party campaigning is banned altogether, since the Constitution limits political campaigning to the parties and candidates themselves. However, especially online, many individuals and organizations launch political advertisements in support of a party or candidate, but this remains unchallenged by the regulatory authorities. In addition, the costs for these online advertisements by third parties remain predominantly undisclosed (Adetula 2024), posing additional challenges for the transparency of campaign finance.

5.2. Instant messaging applications