Mapping of Election-Related FIMI Enablers and Incentives in the Republic of Moldova

This report was prepared by the Association for Participatory Democracy (ADEPT), with the support of the International Institute for Democracy and Electoral Assistance (International IDEA) and funding from Global Affairs Canada. We extend our sincere gratitude to the authors, Igor Boțan, Petru Culeac and Polina Panainte, for their dedicated efforts in drafting this report.

We would like to acknowledge the cooperation of the representatives of the Central Electoral Commission, the Security and Intelligence Service, the Office for the Prevention and Combating of Money Laundering, the Audiovisual Council, the Center for Strategic Communication and Countering Disinformation, the General Inspectorate of Police and the Administration of the President of the Republic of Moldova, whose input greatly informed the research.

Our appreciation also goes to the Independent Journalism Center, the Association for Independent Press, WatchDog.MD, Transparency International Moldova and Ziarul de Gardă, as well as to independent experts Vitalie Esanu and Victor Gotișan, for their valuable insights and contributions.

We are further grateful to Khushbu Agrawal, Sebastian Becker, Sumit Bisarya, Alberto Fernandez Gibaja, Yukihiko Hamada and Natalia Iuras for reviewing various drafts of this report. Special thanks are also due to Lisa Hagman, Jenefrieda Isberg and Anna Ievseieva for their editorial and administrative support.

This report presents an analysis of the enablers and incentives of foreign information manipulation and interference (FIMI) in Moldova’s electoral processes, using a 22-factor analytical framework, developed as part of the project ‘Combatting Election-related Foreign Information, Manipulation and Interference’ implemented by the International Institute for Democracy and Electoral Assistance (International IDEA) with support from Global Affairs Canada. The findings highlight a complex landscape marked by institutional efforts to strengthen democratic resilience as well as persistent vulnerabilities exploited by malign actors, particularly from the Russian Federation. Moldova benefits from a relatively solid legal framework in electoral legislation, audio-visual media regulation and political finance oversight, as well as strong formal commitments to safeguard electoral integrity. Media pluralism provides access to relatively diverse information. Yet these strengths are offset by low public trust in institutions, a fragile party system and widespread socio-economic vulnerabilities, all of which increase susceptibility to manipulation. The fragmented and multilingual media environment, combined with the absence of regulation of online platforms, allows malign actors to distort public discourse, particularly during elections. Domestic proxies, including politicians, media figures, clergy and businesspeople, aligned with foreign agendas continue to amplify FIMI operations, often exploiting geopolitical polarization rooted in debates over European integration, identity and historical grievances. Additional risks stem from illicit foreign financing, including cryptocurrency transfers and cash inflows, as well as opaque online political advertising, often linked to third-party actors. Authorities have strengthened coordination and response mechanisms, but enforcement remains uneven, and global platforms provide little cooperation.

To address these challenges, the report recommends strengthening institutional resilience, safeguarding electoral integrity (including campaign finance transparency) and building societal resistance to disinformation. At the institutional level, the Center for Strategic Communication and Countering Disinformation (CSCCD) should be empowered as a national task force, coordinating the Central Electoral Commission (CEC), the Security and Intelligence Service (SIS), the Audiovisual Council (CA) and law enforcement. The Audiovisual Council’s mandate should gradually extend to digital media, with safeguards for media freedom. Targeted amendments to the Electoral Code are needed to define FIMI as an electoral violation and to ensure that electoral laws in Gagauzia are aligned with national standards.

A second set of proposed measures addresses online campaigning. Moldova should establish mechanisms to monitor digital campaign spending, create a public registry of third-party actors and political ads, and enforce disclosure requirements for influencers and contractors. These efforts need to be matched by legal obligations for global platforms like Meta, Google, TikTok and Telegram to cooperate with Moldovan authorities, ideally linked to European Union regulatory frameworks such as the Digital Services Act. Formal cooperation agreements, rapid-response channels, and secure data-sharing systems are essential for detecting inauthentic behaviour and electoral manipulation. Finally, civic resilience must be reinforced. Media and digital literacy should be integrated into education and supported by non-partisan civic campaigns targeting vulnerable groups. Public-interest journalism and fact-checking require sustainable support, including transparent funding and an early-warning system for viral disinformation. Transparency requirements for foreign-funded organizations and a public list of actors engaged in disinformation would further limit domestic vulnerabilities. These measures should be consolidated into a national strategy on electoral information security and resilience, aligned with Moldova’s EU accession process and reviewed regularly with civil society involvement.

This report provides a structured analysis of how foreign information manipulation and interference (FIMI) takes root and operates within the Moldovan electoral environment. The primary goal of the report is to map the key enablers and incentives that allow such interference to persist, while consolidating operational and contextual knowledge on the subject. The findings are not intended as a theoretical exercise but rather as a basis for practical measures to strengthen the resilience of Moldovan democratic institutions. By drawing together evidence from desk research and in-depth interviews, the report seeks to inform both policymakers and practitioners, offering a clearer picture of the vulnerabilities that shape Moldova’s information space and electoral processes, and providing actionable recommendations on how they might be addressed.

Country context

The Republic of Moldova represents a particularly challenging environment for examining FIMI. As a small state on the frontier of Europe’s security landscape, it has long been exposed to various forms of external interference. The early 1990s brought the experience of a separatist conflict supported by Moscow, followed by years of economic embargoes and political destabilization campaigns. These forms of pressure were later joined by extensive information warfare, overt support for domestic political actors with pro-Russian agendas and vote-buying schemes. Such hybrid tactics intensified following the outbreak of Russia’s full-scale war in Ukraine, underlining the vulnerability of Moldova’s institutions and society to manipulation.

Moldova’s democratic system is underscored by multiple challenges. The electoral landscape combines elements of proportional representation in parliamentary and local council elections with majoritarian for presidential and mayoral elections. The political party system is also relatively weak, with parties competing in a highly fragmented political system where many lack stable structures or deep social roots. Closed party lists and weak internal democracy have often undermined accountability. Oversight institutions such as the Central Electoral Commission (CEC), the Audiovisual Council (CA), the Security and Intelligence Service (SIS), and the Center for Strategic Communication and Countering Disinformation (CSCCD) are the first lines of defence against outside interference and hybrid warfare, but their capacity and credibility are constantly contested by opposition actors. In general, public trust in state institutions is low, and many citizens see these institutions as politicized or ineffective. Widespread emigration and poverty have further eroded society’s resilience, creating a large population that is susceptible to both material incentives and manipulative narratives.

At the same time, Moldova’s information environment is quite pluralistic on the surface. Citizens can access a wide variety of sources in Romanian, Russian and other languages. Independent journalism exists and plays an important role but is also affected by a series of challenges such as poor financial sustainability. This pluralistic environment is fragmented across linguistic, cultural and geopolitical lines. As authorities have consolidated their efforts to curb disinformation and manipulation, online spaces, especially closed messaging platforms, have grown in importance as an ecosystem where divisive narratives flourish unchecked. Against this backdrop, Moldova’s geopolitical polarization, anchored in disputes over European integration, identity and historical memory, creates fertile ground for foreign interference, particularly during electoral periods. At the same time, this complex context makes Moldova a suitable case study for understanding how FIMI exploits structural vulnerabilities in young democracies.

Methodology

The definition of FIMI used in this report derives from the one proposed by the European External Action Service (EEAS), which describes FIMI as an intentional and coordinated manipulative activity by a foreign state or non-state actors (including their proxies inside and outside of their own territory) that threatens or has the potential to negatively impact values, procedures and political processes.

The report is based on the methodology developed by International IDEA to support the mapping of the factors that shape information ecosystems and make them vulnerable to foreign information manipulation and interference. The goal is to empower civil society actors to conduct analysis, build relevant operational and contextual knowledge, and ultimately formulate policy and practical action points tackling multiple aspects of election-related FIMI. The methodology was developed as part of the project ‘Combatting Election-related Foreign Information, Manipulation and Interference’ implemented by International IDEA with support from Global Affairs Canada, which aims to support resilient and gender-sensitive democratic societies that can effectively counter election-related FIMI. The framework consists of 22 factors—including social, political, cultural, economic, technological and legal—grouped into two sets: enablers that make electoral FIMI possible and incentives that make it profitable for a range of actors to engage in FIMI actions. While the emphasis falls on FIMI related to elections, many of the structural enablers and incentives are embedded in Moldova’s broader political and media environment.

In the case of the Republic of Moldova, data about these enablers and incentives was collected using a twofold approach. First, the research team conducted extensive desk research, reviewing publicly available evidence on FIMI enablers and incentives in Moldova, including official documents and legislation, assessment reports produced by international institutions, investigative journalism and news articles. Second, the research team conducted 14 in-depth semi-structured interviews with key stakeholders and experts, primarily face-to-face. The interviewed stakeholders represent a range of sectors relevant for the research, including independent media experts, civil society organizations specialized in media and democracy promotion (such as the Independent Journalism Center and the Association of Independent Press), and senior officials from key state institutions such as the CEC, the SIS, the CSCCD, the CA, the Police General Inspectorate and the Office for Prevention and Combating of Money Laundering.

Given the complexity and specificity of the FIMI phenomenon, this report was subject to several methodological limitations. Although the analysis aimed, to the extent possible, to cover the 2014–2024 period, data availability varied significantly. The desk research was based on publicly accessible information, and the interviews with key stakeholders and experts were conducted to collect data not available in existing publications, but also to validate, contextualize and enrich the desk-research findings. Insights from interviewees are not directly attributed, and only that information that was not explicitly flagged as confidential or off the record was used substantively in the analysis. In some cases, sensitive or confidential information was shared with the researchers to inform and guide the analytical direction of the research and was not quoted or explicitly referenced in the text. Nevertheless, despite these acknowledged limitations, by triangulating between multiple sources and perspectives, the report offers one of the most comprehensive mappings of the factors that enable and incentivize FIMI in Moldova’s electoral processes to date. Still, the report does not claim to exhaust the subject of FIMI in Moldova but to provide a structured, evidence-based mapping that can serve as a basis for further research and policy design.

Report structure

The report is structured in two parts. The first part, dedicated to the analysis and mapping of the FIMI enabling factors, begins with Moldova’s political institutions and practices, then examines the broader social, political and cultural environment, followed by the media sector, digital platforms and the legal and regulatory framework. The second part of the report turns to the incentives for FIMI, including the dynamics of the attention economy, political advertising, foreign funding and the information manipulation industry. The report closes with a synthesis of conclusions and a set of policy recommendations aimed at strengthening Moldova’s resilience against electoral interference. Together, these sections offer a comprehensive picture of how FIMI operates in Moldova, and what can be done to counter it.

Preview of findings

The conclusions in the report point to a dual reality, that of a society caught between resilience and vulnerability, one where reforms and civic activism coexist with persistent structural weaknesses that foreign actors can readily exploit. This tension is particularly visible in electoral cycles, when manipulative narratives, illicit funds and polarizing discourses grow in intensity, testing the resilience of the Moldovan authorities. On the one hand, Moldova has strengthened its legal framework for elections, party financing and media oversight, while making progress towards alignment with European standards. Authorities have also taken steps to block overtly foreign-controlled media outlets, to refine the role of the CEC and to criminalize electoral corruption. These are complemented by the efforts of civil society organizations and independent journalists, who have built significant expertise in exposing disinformation and illicit financing. On the other hand, considerable vulnerabilities remain: public trust in democratic institutions is chronically low, parties are fragile, and citizens face daily socio-economic pressures that heighten their susceptibility to manipulation. Domestic proxies such as politicians, media figures, certain clergy representatives and business actors continue to be involved in amplifying foreign narratives. Online media spaces are fragmented and insufficiently regulated, making them a fertile ground for coordinated inauthentic behaviour and manipulative advertising. Illicit foreign financing, often carried out with the help of illicit cash or cryptocurrency channels, has repeatedly threatened to undermine the integrity of Moldovan elections. While authorities have responded with greater coordination, their efforts remain largely reactive, constrained by limited capacity and incomplete cooperation from global platforms.

Taken together, these findings highlight both the progress and the persistent challenges facing Moldova’s democratic system. The chapters that follow unpack these dynamics in greater detail, providing the factual basis for the conclusions and recommendations set out at the end of the report.

Enabler 1. Systemic lack of trust in democratic institutions

Democratic institutions in Moldova operate under sustained pressure, balancing public expectations, the process of European integration and rapid reforms while facing systemic vulnerabilities: low trust, fragile parties, weak administrative capacity and the emigration of educated citizens. Although the legal framework for transparency exists, implementation is inconsistent. Added to this are persistent threats of Russian interference through disinformation, illicit financing and hybrid tactics. As a result, despite progress towards European standards, Moldova continues to be ranked as a ‘flawed democracy’, reflecting unresolved issues of legitimacy, governance and external vulnerability.

The quality of Moldova’s institutions remains uneven, showing both reform momentum and structural weaknesses. EU candidate status (2022) and accession talks (2024) spurred development and scrutiny, yet democratic consolidation is hampered by politicized administration, a fragile party system, low public trust and human capital flight. These issues limit institutional independence, efficiency and transparency. A critical assessment of Moldova’s democratic institutions requires triangulating citizens’ perceptions, evaluations by independent bodies and EU progress reports, which together reveal a complex picture of cautious progress under pressure.

These vulnerabilities are explored through three main lenses: citizens’ perceptions according to opinion surveys; evaluations by national and international institutions; and assessments by EU institutions since obtaining EU candidate status in 2022 and the start of accession negotiations in 2024. Citizens’ perceptions are reflected periodically by the Barometer of Public Opinion. According to the October 2024 survey, only 42 per cent believe Moldova is governed by the people, while 49 per cent think the opposite. Trust in institutions is generally low: the Church is most trusted (64 per cent) and parties least (10 per cent) (Institutul de politici publice 2024). This climate provides fertile ground for FIMI techniques. From an external perspective, according to the Economist Intelligence Unit Democracy Index, Moldova is classified as a flawed democracy (Economist Intelligence Unit 2025), scoring 6.04 (out of 10) in 2024, and ranking 71st out of 167 countries, three places lower than in 2023. Complementing this picture, International IDEA’s Global State of Democracy data set places Moldova mid-range across its categories of democratic performance in 2024: 69th out of 173 on Representation, 52nd on Rights, 64th on Rule of Law and 85th on Participation (International IDEA n.d.). Despite a series of shortcomings, the European Commission considers Moldovan political institutions functional enough to recommend to the European Council, based on the Republic of Moldova 2023 Report (European Commission 2023), the start of accession negotiations with the EU.

The transparency of democratic processes in the Republic of Moldova has evolved, starting with the adoption of the Law on Access to Information in 2000 (Law No. 982 of 11 May 2000), followed by the adoption of the Law on Transparency in the Decision-Making Process (Law No. 239 of 13 November 2008). These laws established the cooperation framework between public authorities and civil society and defined the mandatory stages of the decision-making process. The portal Particip.gov.md contains all information on the draft laws consulted with the public and adopted.

The legitimacy of Moldova’s democratic institutions and elections remains a recurring debate, largely due to the politicization of regulatory bodies. The Constitutional Court, drawing on European Court of Human Rights jurisprudence, has stressed that while political institutions derive legitimacy from elections, regulatory institutions depend on neutrality and professionalism. Historically, elections have been contested over weak governance, legal shortcomings and foreign interference, at times leading to political conflict and unrest. Today, the greatest threats are external interference, illicit party financing, propaganda and manipulation. The opposition continues to question the neutrality of institutions such as the CEC, though the new Electoral Code addresses this by reforming CEC appointments in 2026, when seven members of the future CEC will be appointed for six-year terms by the following institutions: the Presidency, the Government, the Superior Council of the Magistracy, the Parliament (including one from the opposition) and civil society.

Conflicts and irregularities have long undermined Moldova’s electoral process, creating openings for foreign information manipulation. Such problems date back to the 2005 parliamentary elections, when authorities expelled hundreds of Russian ‘observers’ for interference (Newsru.com 2005). At various points, the legitimacy of institutions like Parliament and the Presidency was questioned after disputed elections, most notably the April 2009 parliamentary vote, when allegations of voter list fraud and abuses against the opposition triggered the ‘Twitter Revolution’ (Hale 2013), mass riots and the burning of state buildings, ultimately forcing early elections. High-profile cases continued in subsequent years, including the exclusion of the Patria Party from the 2014 elections (European Court of Human Rights 2020), the annulment of the 2018 Chisinau mayoral results (Chișinău Court (Centru) Decision No. 3-701/2018 of 19 June 2018) and repeated exclusions of Șor Party candidates for campaign finance violations (Republic of Moldova 2023). To address these issues, a new Electoral Code was adopted in 2022 based on recommendations from the Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe (OSCE) Office for Democratic Institutions and Human Rights, and the CEC continues refining the framework with input from parties, civil society and the Coalition for Free and Fair Elections.

Moldova’s electoral system combines proportional representation for parliamentary and municipal councils with majoritarian voting for presidential, mayoral and regional posts. A key vulnerability of the proportional system is the use of closed party lists, often criticized for favouritism and corruption. Authorities acknowledge flaws in the single national constituency model but retain it to facilitate voting abroad and the participation of residents from Transnistria. This is exploited by Russia, which has also shaped Gagauzia’s gubernatorial elections since 2010, with candidates seeking endorsements from Moscow or the Russian Orthodox Church, and the 2015 elections, sparking scandal over direct Russian participation (RBC.ru 2015). The most recent example came during the 2024 presidential elections and referendum, when some 150,000 bank accounts were opened for Moldovan citizens through Promsvyazbank, linked to Russia’s Defence Ministry, as documented by the Moldovan Intelligence and Security Service (SIS 2024).

Enabler 2. Inadequate political finance regulations

Moldovan authorities have strengthened political finance regulation over time, particularly after systemic abuses by oligarch-controlled parties that undermined fair competition and entrenched state capture. Yet FIMI actors have diversified tactics, channelling illicit funding through cash, banking and cryptocurrency. Authorities introduced measures to curb these practices, but persistent issues remain.

The regulatory framework governing political finance in Moldova has seen formal improvements, particularly through the new Electoral Code, which enhanced the oversight role of the CEC. Although 80 per cent of the 66 registered parties submitted financial reports on time, other issues such as low data quality and issues with transparency of wealth declarations remain. As a result, the CEC admitted only 35 parties to the 2025 parliamentary elections (alegeri.md n.d.). Among the parties that were not allowed to participate in the 2025 parliamentary elections are four entities from the Victoria Bloc (Popușoi 2025), created in Moscow in 2024 by the former Șor Party leader (whose party was declared unconstitutional in 2023 for illegal financing), and that risk dissolution under current law.

The Electoral Code defines campaigning as ‘actions to disseminate information aimed at determining voters to vote for one or another electoral competitor’ that can be carried out ‘through the media, by displaying electoral posters or through other forms of communication’, thus including in the online environment. However, the Code lacks specific rules for digital activities despite rising online campaigning in recent electoral cycles confirmed by monitoring reports. Promo-LEX (2025a) estimated that in the 2024 presidential elections, about one-third of campaign activity occurred online, with little transparency on funding sources. Monitoring is hampered by weak mechanisms: Google (including YouTube) provides no electoral spending reports, and Facebook’s ad library is opaque about the real financiers.

Recent elections revealed multiple methods of illegal financing: cash smuggling, bank transfers and cryptocurrency transactions. Authorities have made efforts to combat these forms of interference, but the response has been mainly reactive. Preventive regulations require a deeper understanding of interference mechanisms across banking, cryptocurrency and digital systems, while ensuring proportionality and the protection of citizens’ rights. This is particularly important especially given Moldova’s efforts to align with emerging EU standards in this area. After the 2024 presidential elections and referendum, the Parliament debated reports from law enforcement and oversight bodies involved in combating foreign influence, and identified several measures to reduce foreign interference, with particular attention given to combating electoral corruption through illegal financial flows from abroad. As a result, the Parliament adopted Law No. 100 of 13 June 2025, on Amending Certain Normative Acts (Combating Electoral Corruption and Related Aspects). The effectiveness of these measures will become clear only after full implementation.

The authorities’ ability to track and verify online spending for political purposes is relatively limited and relies on self-reported party data that can understate true costs. Unregistered, formally unaffiliated third parties (non-campaign spenders) may actively campaign for official competitors with undisclosed resources, making their financing nearly impossible to identify, thus allowing for unaccounted parallel campaign spending. The CEC estimated that actual online promotion costs through third parties were roughly triple the official reported amounts (Law No. 100 of 13 June 2025). To address this issue, in 2024 the CEC initiated a dialogue with Meta, Google and TikTok and although initial cooperation was limited, a June 2025 meeting (Radio Moldova 2025) with Google and Meta showed more willingness to collaborate on combating disinformation and illegal financing issues. Discussions focused on ensuring transparency in online advertising and disclosure of funding sources, though concrete implementation details remain undefined.

Enabler 3. Polarized and divided public discourse

Public discourse in Moldova has become increasingly polarized, shaped by historical, geopolitical and identity-based divides. Pro-Russian forces exploit themes such as fear of war, economic hardship and the energy crisis to revive nostalgia for Russian ties and undermine European integration. Russian officials and intelligence services periodically frame Moldova as the next Western ‘anti-Russia project’. While incidents of hate speech against LGBTQ+ groups have declined due to legal changes, public demonstrations still provoke opposition-led countermarches.

Polarization is currently fuelled above all by Russia’s aggression against Ukraine, which has revived older conflicts: Moldovan versus Romanian linguistic identity, the choice between European and Eurasian integration and symbolic commemorations (Europe Day versus Victory Day). These overlapping discourses deepen the cleavage between pro-EU forces condemning Russian aggression and those justifying or avoiding its condemnation.

Narratives that foster fear and uncertainty have the strongest polarizing effect. Pro-Russian actors claim that Moldova’s solidarity with the EU and Ukraine violates its neutrality and risks dragging the country into war. Opinion polls show that the share of citizens fearing war increased approximately 10-fold (Institutul de politici publice 2023), from 3 per cent to 36 per cent, after Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. These discourses are often amplified by Russian officials. Russian Foreign Minister Sergei Lavrov and others have repeatedly asserted (GagauzInfo.md 2022) that the West seeks to turn Moldova into ‘a second Ukraine’, a narrative echoed by Russian intelligence services, which spread propagandist articles online under titles such as ‘Lessons of Western “democracy” for Moldova’ (Sluzhba vneshnei razvedki Rossiyskoi Federatsii 2024). Such narratives are circulated widely in Moldovan media and digital spaces, reinforcing societal division.

Gender and LGBTQ+ rights remain another sensitive issue. Although overshadowed by the regional security crisis, the theme is maintained by parties promoting ‘sovereignty’ and ‘traditional values’, as opposition to ‘propaganda’ in schools or public life. Polls over the past decade (Institutul de politici publice 2014) show a persistently negative societal attitude towards LGBTQ+ people, though tolerance is higher in urban areas. According to Rainbow Europe, Moldova ranks 37th out of 49 countries for LGBTQ+ rights. International (OSCE/ODIHR 2024) and national (Promo-LEX 2025b) monitoring missions for the 2024 presidential elections noted dozens of hate messages targeting this group, though experts observed a decline due to amendments to the Contravention Code (articles 52 and 70) and Criminal Code (article 346) in 2022, which established or reinforced sanctions against hate speech, incitement to discrimination, and calls to hatred or violence on grounds of prejudice, with article 52 of the Contravention Code specifically targeting such practices in the electoral context.

Enabler 4. Exclusionary and antagonistic political discourse

Exclusionary rhetoric in Moldova mainly exploits identity issues such as the Moldovan–Romanian language debate, minority status or the country’s geopolitical orientation. While chauvinism and racism are rare, populism is growing, mixing nationalism, conspiracy theories and foreign-funded voter manipulation. Civil society, regulators and international partners have provided effective counterweights against hate speech.

Identity issues are topical in the Republic of Moldova. According to the 2024 census (Biroul Național de Statistică al Republicii Moldova 2024), Russian-speaking ethnic groups constitute approximately 15 per cent of the country’s population, and most of them do not know the official language—Romanian. The majority Moldovan–Romanian ethnic group is bilingual (they speak Romanian and Russian), while minority ethnic groups are predominantly monolingual. For a significant part of the ethnic minorities, for ethno-political and geopolitical reasons, the name of the official language—Moldovan versus Romanian—matters more than knowing it for use in public and professional communication. In practice, although the Romanian language has been a mandatory subject in schools in the Republic of Moldova since 1991, the Equality Council reports that most of the complaints it receives refer to common cases of discrimination based on language which is used by political forces in their electoral competition. In recent years, especially against the background of the war in Ukraine, approximately one third of the respondents would vote in favour of a possible referendum for the unification of the Republic of Moldova with Romania, according to opinion polls (Petruţi 2025). This fact is exploited as a scare tactic by FIMI actors regarding the possible loss of the sovereignty and independence of the Republic of Moldova.

Enabler 5. Presence of domestic proxies

Moldovan democracy has long faced Russian hybrid threats, with domestic proxies central to amplifying FIMI operations. Their activities range from spreading pro-Russian narratives and organizing destabilizing actions to running voter corruption networks. Authorities and journalists have exposed some of these proxies however, a weak justice system performance has led to few prosecutions and allowed high-profile figures to escape justice.

According to the EEAS (2023), ‘FIMI proxies’ are individuals or entities acting on behalf of a foreign actor to manipulate information or interfere in political and societal processes. These actors may include politicians, parties, media outlets, journalists, influencers, civil society groups, academia and businesses. In Moldova, two main clusters of Russian proxies can be identified: Russian or foreign nationals (mainly from countries in the Commonwealth of Independent States [CIS]) with a formal legitimate presence in the country, and domestic actors with pro-Russian ideological or financial ties.

Among the Russian entities suspected of engaging in various types of FIMI activities are the Russian embassy in Moldova (NewsMaker 2023a), its diplomats and employees (Deutsche Welle 2023), Russian political advisors (RISE Moldova 2020) and the Russian Center for Science and Culture (IPN.md 2023) in Chișinău, as well as Russian government-organized non-governmental organizations active in the region (e.g. Evrazia) (Veridica 2024). This cluster includes also nationals of other countries (e.g. Serbia, CIS countries) suspected by Moldovan authorities of being involved in preparing or conducting destabilizing activities in Moldova (Euronews Romania 2024). The second cluster consists of Moldovan entities openly promoting or amplifying Russian narratives, supported directly or indirectly through illicit Russian funding (RISE Moldova 2022). It includes pro-Russian politicians (ESP.md 2024) and parties (PRO TV Moldova 2024), local branches of Russian media (SIS 2023c), journalists (Centrului de Investigaţii Jurnalistice 2023), influencers (TV8.md 2024b), clergy (Jurnal.md 2024) and businesspeople (IPN.md 2024). Also, part of this cluster includes coordinated informal networks operating without an official legal or political personality, such as Ilan Shor’s voter corruption scheme (Ziarul de Gardă 2024b), which mobilized citizens through bribery, multi-level-marketing recruitment and communication via Telegram groups and chatbots.

The breadth of these clusters highlights the scale of Russian FIMI in Moldova. Activities of Russian entities, local media and political actors are ongoing, while others, such as journalists, influencers and businesspeople, are mobilized closer to elections. Media investigations into Ilan Shor’s vote-buying network suggest that money is an important incentive used to mobilize participants, though interviewed interlocutors noted that non-material factors, such as a sense of belonging, might represent an important driver among the network members.

Discussions carried out with key stakeholders indicate that authorities are aware of the activities of proxy FIMI actors, with multiple institutions closely cooperating and exchanging information to prevent or reduce the potential damage caused by proxy actors’ activities. Furthermore, investigative journalists periodically publish materials helping uncover proxy actors’ illegal activities.

Despite these efforts, authorities often respond slowly, and prosecutions remain inconsistent. Although multiple cases of political corruption, electoral bribery and illegal party funding have been uncovered and fines levied, two members of parliament (Alexandr Nesterovschi and Irina Lozovan) escaped before sentencing, and few FIMI-linked actors have been prosecuted. This in turn leaves an impression of impunity, detrimental to any authorities’ efforts to discourage the Moldovan population from joining illegal FIMI-related activities.

Enabler 6. Audience susceptibility to manipulation

Although it was not possible to identify publicly available research data on the susceptibility of Moldovan audiences to information manipulation and disinformation, there is a general perception that Moldovan society is highly vulnerable to FIMI due to several ingrained factors such as the multilingual character of the majority of Moldovans, the availability of diverse content from Russian sources, low media literacy, poor economic status and the high level of distrust in the authorities. FIMI actors often target vulnerable groups from Russian-speaking ethnic minorities and citizens who express nostalgia for the Soviet Union. Civil society organizations (CSOs) have taken an active role in countering disinformation, but these efforts are not sufficient, and long-term solutions require a nationwide effort to improve media literacy. The Moldovan state has responded by, among other things, strengthening the legal framework, including the laws on the audio-visual media and political finances, as well as by establishing the CSCCD.

According to sociological research, over 80 per cent of respondents in the Republic of Moldova say they use the Internet daily, but the Independent Journalism Center notes that currently there is no tool to assess the degree of information and media literacy among citizens at the national level (MediaCritica 2025).

Young and middle-aged generations acquire digital skills naturally through formal education or out of necessity at their workplace. To strengthen the media and digital literacy of older generations, the development and broadcasting of educational TV programmes could be considered. These should be presented in an accessible, engaging, even humorous style in order to capture audiences’ interest without causing fatigue, and there are examples in this regard (TV8.md 2023).

Enabler 7. Lack of media pluralism and independence

Moldova’s media landscape is diverse, with numerous TV stations, online outlets and social media creators. This pluralism, supported by a stronger legal framework, enables the expression of varied viewpoints, including those of the opposition. At the same time, authorities’ efforts to strengthen media independence, counter disinformation and enhance security have reduced Russian propaganda but also prompted accusations of overreach and have pushed banned outlets onto online alternative platforms. Persistent challenges include weak financial sustainability, donor dependence, a limited advertising market, content overlap and unfair competition. Additional concerns involve opaque online ownership, political bias and censorship in regional public broadcasting.

Moldova’s media pluralism is reflected in 41 active TV stations (Durnea 2025), 61 radio stations (Consiliul Audiovizualului al Republicii Moldova 2025), over 400 rebroadcast foreign TV channels (Consiliul Audiovizualului al Republicii Moldova 2024b), 70 newspapers (Media Guard Association n.d.a) and numerous online outlets. The public broadcaster Moldova 1 is the second-most-watched station and generally balanced, while the regional GRT TV in Gagauzia suffers from political control and censorship (IJC 2024) and was sanctioned in 2024 for false and toxic narratives (Ziarul de Gardă 2024a). Most rebroadcast foreign channels originate from Russia (188), followed by Romania (87), Ukraine (31) and the United Kingdom (30). Estimating the scale of online media is challenging, since Moldova does not currently have a register of online media. Over 100 online news outlets operate, with about 12 leading in audience reach (Gemius Audience (e-Public) n.d.). Content creators (including influencers, journalists and politicians) are active on YouTube, TikTok, Instagram and Telegram. As of January 2024, Moldova had 1.58 million active social media user identities (DataReportal 2024). Estimates in 2024 put Facebook users at 1.30 million and Instagram users at 1.03 million, with surveys showing that 28 per cent of Moldovans get news from TikTok (DataReportal 2024; Media Guard Association n.d.b). These platforms play a central role in the information space due to their reach and audience reliance.

In theory, this diverse landscape enables the expression of multiple viewpoints, including pro-European, pro-Russian, independent and investigative voices. The existing legal framework formally guarantees freedom of expression and access to information, and several independent platforms, particularly in the online space, have built reputations for high-quality, balanced journalism and critical analysis. However, this pluralism is challenged by several structural and political constraints. Outlets increasingly cluster along the East–West geopolitical divide that also shapes society at large. There is a high content overlap across the media, with many outlets rebroadcasting information, as limited finances discourage original production (Durnea 2025). A certain decrease in the plurality of opinions represented in the mainstream traditional media was caused by recent government efforts to combat disinformation, particularly Russian-sponsored narratives. Although justified in the name of national security (Dodon 2024), this has also drawn accusations of overreach and censorship from the opposition (Radio Chișinău 2022) and civil society (IJC 2023) alike. Nevertheless, banned media outlets (SIS 2022;

Freedom House (2024) rates Moldova’s media independence at 3 out of 7, a score unchanged for five years. This reflects persistent structural problems alongside gradual reforms. Notable improvements include a new advertising law, formalized must-carry obligations and the creation of the CSCCD. Despite these advances, Moldova’s media continues to face high risks of ownership and audience concentration (Media Guard Association n.d.c). Major outlets remain in the hands of influential business figures with broader commercial interests. Regulatory reforms reduced the role of politically exposed owners in TV and radio, bringing some diversity, but concentration persists. Online media ownership is even less transparent, and past efforts to improve disclosure have failed. In this context, one of the sector’s most pressing issues remains financial independence. Media outlets are trying to expand advertising and exploring subscriptions or crowdfunding, but such methods cover only 5 to 10 per cent of operating costs (Durnea 2025). This leaves most media financially fragile and heavily dependent on external funding, undermining long-term sustainability.

Enabler 8. Poor journalism and low journalistic standards

Moldovan journalism has improved in recent years but still struggles with several issues. Formal education remains misaligned with market needs, producing skill gaps and staff shortages. Combined with financial constraints, this pushes outlets to rely on rebroadcasting foreign content at the expense of original production, a practice that can influence public opinion and pose security risks. Mainstream journalists are generally well equipped to detect information manipulation; however, the shift of harmful content to online media and unregulated messaging apps threatens to undermine fact-checking effectiveness.

The quality of journalism in Moldova remains constrained by weaknesses in education, newsroom capacity and media integrity. The 2024 State of the Press Index scored the quality of journalism at 33.66 out of 60, highlighting persistent problems such as relatively weak pluralism and uneven content quality (Durnea 2025). Although the media landscape appears diverse, most outlets are generalist, with little local or thematic coverage. Journalism education, particularly at the State University of Moldova, is poorly aligned with market needs: curricula lack practical anchorage, staff are under-qualified or disconnected from newsroom realities, and low wages discourage experienced journalists from taking up teaching roles. As a result, newsrooms face shortages of skilled reporters, editors and technical staff. Alternative programmes, such as the School of Journalism of Moldova and continuous training offered by CSOs and donors, provide a more focused education avenue to consolidate journalists’ professional capacities, though not all newsrooms are able to participate because of staff constraints.

Moldova’s media environment also struggles with content quality and integrity. Many media outlets lack the resources or interest in producing local content, relying instead on rebroadcasting foreign entertainment, especially Russian-produced movies and shows, which dominate screens and subtly reinforce pro-Russian sentiment, posing security risks. The 2024 Press Situation Index also highlights poor-quality journalism, including partisan content and deliberate misinformation. While mainstream outlets generally adhere to ethical norms and mechanisms like the Code of Ethics for Journalists (Consiliul de Presă din Republica Moldova 2024), enforcement remains weak. The Press Council promotes self-regulation but requires reform to more effectively address serious ethical violations.

Discussions with key stakeholders point to the fact that Moldovan journalists are generally well informed and trained regarding the skills necessary for detecting, checking and responding to false information and manipulative narratives. Still, these capacities may prove increasingly insufficient in the context of the evolving nature of information manipulation, with a lot of harmful content spreading rapidly and with little visibility in the unregulated online space, especially in closed messaging apps and private social media networks. This shift severely limits the reach and impact of conventional fact-checking and debunking efforts, as these often fail to reach the same audiences that consume the original manipulative content.

Enabler 9. Decline in trust in mainstream news sources

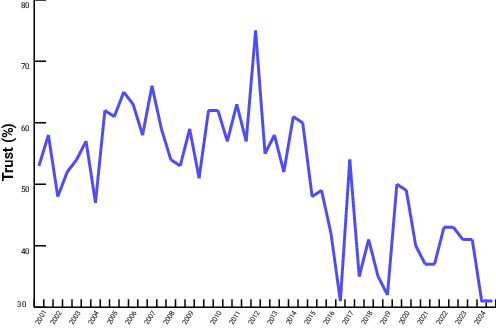

Public trust in Moldovan media remains low and continues to decline. The 2024 Public Opinion Barometer shows that 39.9 per cent of respondents have little trust and 23.6 per cent have none, while only about 31 per cent express some trust in traditional media and 29 per cent in digital outlets (Institutul de politici publice 2024). As seen in Figure 3.1, although trust levels have fluctuated over the past decade, the overall trend is downward. Still, compared with other institutions, media remains among the top five most trusted, following the Church (64 per cent), local public administration (55 per cent) and the President (36 per cent).

Traditional media, especially television, remains the main source of information for most Moldovans, though in the capital it is increasingly replaced by online outlets and social media. The Public Opinion Barometer shows that 37 per cent of Moldovans rely on television, 21 per cent on social networks, 16 per cent on online news sites and 9 per cent on family. Trust rankings differ, however, with television leading with 25.8 per cent, followed by family (13.1 per cent), online news sites (12 per cent) and social media (10.2 per cent). Bloggers, vloggers and influencers are cited as important or trusted by only about 2 per cent of respondents (Institutul de politici publice 2024).

A 2024 survey by the International Republican Institute shows Moldovans rely mainly on television (71 per cent), social media (61 per cent), Internet news sites (60 per cent), relatives and friends (30 per cent), and radio (24 per cent) for political news (IRI 2024). In Chisinau the ranking shifts, with Internet news sites leading (77 per cent), followed by social media (69 per cent), television (64 per cent), relatives and friends (26 per cent), and radio (13 per cent). The same poll highlights the most used platforms: Facebook, YouTube, TikTok, Instagram, Viber, Telegram, Messenger, WhatsApp, Odnoklassniki, VKontakte and X (previously Twitter).

Low trust in Moldovan media may be explained by a combination of structural weaknesses, quality issues and audience exposure to manipulative content. Media outlets compete to deliver news rapidly, reflecting global trends where speed often outweighs depth. This is not problematic if backed by strong quality control and ethics, and many traditional outlets now apply such safeguards, supported by legal reforms and oversight from the CA and the Press Council. These bodies, through warnings, public statements or fines, help ensure a certain degree of professional accountability. Still, given the absence of meaningful regulation of online platforms, some online media outlets resort to misleading headlines, manipulation or exaggerated framing techniques that stretch the truth without formally breaking the law.

Furthermore, audiences increasingly rely on informal channels as filters for information, with family being among the most trusted channels of information along with TV, followed by online outlets and social media. While family and social networks may not be ‘alternative’ in a strict sense, they function as primary filters through which individuals increasingly access and disseminate information. Closed messaging apps such as Telegram and Viber are gaining prominence as spaces for sharing news in groups or personal networks. These platforms are often used to amplify FIMI-aligned narratives spread by local proxies, fuelling panic and tension. Their opaque and unmonitored nature, combined with low media literacy in rural areas, makes them influential yet difficult to regulate. Interviewed experts note that much of today’s disinformation circulates specifically through these channels.

Enabler 10. Influence of foreign-aligned media

Most of the Moldovan population is multilingual and can consume Russian language media content, making it vulnerable to Russian Federation FIMI, as already seen in recent elections. After authorities banned several foreign-aligned media outlets, the FIMI ecosystem adapted, shifting information manipulation efforts to social media platforms and messaging apps like Telegram.

The foreign-aligned media outlets that have the possibility to exert an influence on the Moldovan population can be grouped into two categories: (a) foreign-owned media outlets (Sputnik, RIA Novosti, KP, Tass, AIF, Pravda, etc.) that generate and promote Kremlin official narratives; and (b) domestic media outlets affiliated with the Kremlin that rebroadcast its narratives or produce their own content resonating with and amplifying general pro-Russian messages. One can estimate the breadth and scale of such media outlets based on an analysis of the decisions of the Moldovan Security and Information Service which banned more than 70 online media outlets and 12 TV stations that ‘distort the content of information disseminated in the public space, or originate from public authorities of a state engaged in military conflict and recognized as an aggressor state’ (decisions taken in February 2022 (SIS 2022), January 2023 (SIS 2023a), March 2023 (SIS 2023b), October 2023 (SIS 2023c) and over the course of 2024 (NewsMaker 2023b)). The bans were imposed by the Moldovan authorities in the context of the state of emergency declared at the start of the war in Ukraine and increasing levels of propaganda and disinformation. Most of these media outlets occupied a marginal position according to opinion polls and online audience measurements (Gemius Audience (e-Public) n.d.). It is important to mention that, after being banned, many of these news websites ceased to exist or migrated to alternative domains such as

Enabler 11. Fragmented digital information environments

Moldova’s digital information space is fragmented on both the supply and demand sides, shaped by technological change and geopolitical, linguistic and ideological divides. These fractures reduce shared discourse and amplify echo chambers. These dynamics pose serious risks to social cohesion and yet remain insufficiently studied.

The fragmentation of the digital environment reflects both the proliferation of media outlets and platforms and the splitting of audiences across different dimensions (Nielsen 2025). It manifests as platform fragmentation (diverse and non-overlapping channels), content fragmentation (different forms and themes of information) and narrative fragmentation (conflicting worldviews).

In Moldova, fragmentation is shaped by geopolitical and linguistic divides, as well as platform preferences and communication practices. Digital technologies facilitate personalized access to information, but also create segmented audiences lacking shared facts, which increases polarization and weakens democratic discourse. A key axis of content fragmentation is the East–West divide, separating political allegiances and linguistic communities. Most high-audience mainstream media reflect a pro-European line, leaving Russian-speaking or Russia-leaning audiences underserved. Exceptions like NewsMaker.md and Nokta.md provide balanced Russian-language content, but many citizens instead rely on informal ecosystems where alternative narratives circulate unchecked.

Platform fragmentation reinforces these divisions. Different groups use a mix of conventional platforms such as Facebook or YouTube, alongside encrypted messaging apps like Telegram and WhatsApp. This shift towards messaging platforms has decentralized the dissemination of political information and created new dynamics of peer-to-peer influence and group-based mobilization. Messaging platforms are of key importance for this analysis, since they facilitate private or semi-private information flows that escape traditional media scrutiny. These closed networks, ranging from family chats and neighbourhood groups to ideologically homogeneous communities, act as echo chambers in which users are both consumers and distributors of content, often coming from unverifiable or foreign sources, that confirms, supports or reinforces existing narratives within their networks. This fosters divergent understandings of national identity, foreign policy or even basic facts within insulated subcommunities.

According to interviewed stakeholders and monitoring by WatchDog.md and the Institute for Strategic Initiatives, these platforms often serve as alternative media environments promoting narratives hostile to the West, NATO and the EU while amplifying Russian geopolitical messaging. Communication is emotive, identity-driven and algorithmically reinforced, fostering cohesion within groups but detachment from public discourse. This deepens narrative fragmentation, visible especially in electoral years, when foreign and domestic actors mobilize segmented audiences through targeted content. Lacking a shared informational foundation, citizens struggle to engage in constructive dialogue, evaluate electoral messages fairly and resist disinformation and FIMI.

Enabler 12. Exploitability of digital and social media technologies

Moldova’s online environment remains highly vulnerable to FIMI threats due to the lack of regulation of online media, coupled with widespread access to the Internet and the popularity of major social media platforms. Malicious actors use various tactics such as coordinated inauthentic behaviour, manipulative advertising, algorithmic gaming and the weaponization of Telegram for spreading disinformation and activists’ mobilization and coordination. Moldova’s lack of capacities to hold global platforms accountable amplifies these risks, with authorities often relying on informal advocacy to trigger a reaction from tech companies.

Moldova’s information environment is exposed to a broad spectrum of threats. The high levels of Internet penetration, widespread access to smartphones and the popularity of global social media platforms have created a dynamic digital ecosystem. At the same time, this exposes Moldova to the same risks seen in other democracies. These include coordinated disinformation campaigns, artificial amplification through bots (Adiaconitei 2025) and fake accounts (Ziarul de Gardă 2025a) and exploitation of algorithm-driven visibility for polarizing content.

Large platforms such as Facebook, YouTube, TikTok and especially Telegram dominate Moldova’s digital space. Malicious actors often exploit their systemic weaknesses, opaque moderation and inconsistent enforcement. Moldova’s geopolitical position adds to the complexity of the issue: while aspiring to EU standards, it remains outside of EU jurisdiction. Interviewees from civil society and regulatory institutions suggest that Moldova is often treated as a low-priority market by the large platforms, with limited local moderation capacity and minimal investment in safety mechanisms tailored to its political and linguistic context. EU-supported mechanisms, such as temporary escalation channels with Meta, Google and TikTok ahead of elections, help but remain reactive (European Commission 2024). Moldova’s limited technical and legal capacity hampers accountability, forcing authorities to rely on creative approaches to push platforms to act. According to interviewed stakeholders, authorities have resorted to various workarounds such as informal advocacy and lobbying as well as publicity in order to indirectly pressure the large content platforms into taking action with regard to certain online FIMI manifestations.

The messaging platform Telegram holds a particularly influential role as a convenient tool for FIMI actors targeting Moldovan audiences due to its hybrid model, which combines private messaging, public channels and minimal content moderation. It serves as a hub for FIMI activity by disseminating narratives later picked up by mainstream platforms, coordinating campaigns without visibility from regulators or researchers and spreading leaks or compromising materials during politically sensitive moments.

Emerging technologies further amplify the risks. AI-generated content, deepfakes and synthetic media have already targeted President Maia Sandu and CEC chair Angelica Caraman (TV8.md 2024a). Alongside these, cyberattacks such as DDoS attacks, account hijackings (Dermenji 2025) and defacements (Ziarul de Gardă 2025b) have increasingly disrupted electoral processes by undermining media and institutions. Furthermore, impersonation and ‘doppelganger’ operations that imitate politicians, ministries or international organizations spread disinformation and erode public trust, compounding Moldova’s vulnerability.

Enabler 13. Inconsistent and lax moderation policies

While user statistics are available for platforms like Facebook, Instagram and, to a lesser extent, TikTok, there is a notable absence of reliable, publicly available data on the number and demographics of Telegram users in Moldova. This creates a significant blind spot, especially given Telegram’s role as both a messaging app and a content dissemination platform.

Stakeholder interviews suggest that after the suspension or revocation of broadcasting licences for several TV stations and the banning of online outlets associated with pro-Russian narratives (in 2021, 2022 and 2023) an important share of Moldovan audiences migrated to alternative digital channels, including social media platforms and encrypted apps like Telegram. Although there is periodic reporting either by journalists or directly from the platforms (e.g. Meta) regarding the closure of multiple fake accounts (Radio Europa Liberă Moldova 2024) that have been identified to be part of various coordinated disinformation campaigns, platforms apply moderation inconsistently, and in Moldova enforcement mechanisms are limited. At the same time, Telegram goes largely unmoderated. Thus, Russian-language content, still widely consumed by Moldovans, escapes scrutiny, regardless of its origin or intent. It is important to note that exposure to potentially manipulative content on these platforms is not necessarily limited to self-identified pro-Russian audiences. Given the widespread bilingualism in Moldova, Russian-language content, including narratives pushed by Russian state-affiliated actors or their proxies, can reach a broader and more diverse audience. As a result, harmful or misleading content can spread more diffusely, influencing not only politically aligned groups but also the undecided or disengaged segments of the population.

Enabler 14. Ineffective regulatory authorities

Moldova’s audio-visual media is regulated by the CA, which cooperates with the CEC during elections to ensure fair coverage. However, its mandate excludes online content, a growing vulnerability in the information space. Authorities have resorted to ad hoc measures, pushing parts of FIMI activity onto unregulated online platforms and attracting criticism from civil society for exceeding constitutional limits. Recent legislative proposals seek to extend the CA’s role online, but doubts remain about its capacity to manage this without infringing on media freedom and citizens’ rights.

The CA is Moldova’s main media regulator, mandated to oversee audio-visual services, ensure compliance with media laws, guarantee pluralism and transparency of ownership and monitor electoral coverage in cooperation with the CEC. During elections, the CA monitors adherence to editorial policy, issues weekly and final reports, and applies sanctions for violations. Penalties range from warnings and fines of USD 250–5,000 for various violations, including hate speech and the violation of fundamental rights or freedoms. Repeated violations, after progressive measures have been exhausted, may lead to the suspension or revocation of the broadcasting licences of media service providers. CA reports show growing monitoring capacity, though its lack of authority over online media remains a key vulnerability (Consiliul Audiovizualului al Republicii Moldova 2024c).

Beyond the CA, other state bodies have intervened in the information space, especially during crises. The Emergency Situations Commission (ESC), created after Russia’s invasion of Ukraine in 2022, suspended the licences of 12 TV stations linked to oligarchs, including Ilan Shor, citing the need to protect national security and counter disinformation (Diez.md 2022). Civil society groups argue the measure had unintended effects, pushing Russian-speaking audiences towards harder-to-regulate online platforms.

The Council for Strategic Investments, established in 2021 (Law No. 174 of 11 November 2021) to oversee projects of national security importance, has also acted in the media sector. In 2024, it requested data on the effective beneficiaries of investments in eight media outlets. Unsatisfied with the responses, it suspended the licences of three stations over non-transparent ownership (Realitatea.md 2024).

The CA’s role is less contested, as it operates under a solid legal framework regulating TV and radio, as well as clear provisions in Chapter XII of the new Electoral Code on electoral media coverage. Additionally, article 28 of the Code also outlines cooperation between the CEC and other institutions in managing elections. However, regulating the more digital online media requires new experience and safeguards to ensure citizen rights, making it essential to extend this cooperation framework to the online space. Confidence in the CA’s capacity has led legislators to expand its mandate. On 29 May 2025, a bill was introduced to amend the Audiovisual Media Services Code (Republic of Moldova 2025), empowering the CA to apply audio-visual legislation to online platforms and to lead activities in media literacy, research and audience studies. Although some provisions are vague, supporters argue the CA already has experience engaging with major social media companies and will be able to monitor and verify online content, combat disinformation, and act with greater flexibility and authority.

Authorities have recently shown more caution in tightening regulations against disinformation, partly due to criticism of the ESC, though it acted in accordance with the law (Law No. 212, 24 June 2004). Under the state of emergency declared on 24 February 2022 as per Parliament Decision No. 41 of 24 February 2022 (Republic of Moldova 2022), the ESC suspended the licences of 12 TV stations: six in December 2022 (Pervyi Kanal v Moldove, RTR Moldova, Accent TV, NTV Moldova, TV6, Orhei TV) and six more in October 2023 (Orizont TV, ITV, Prime TV, Publika TV, Kanal 2, Kanal 3) (Durnea 2022; Coptu 2023). Reasons cited included ownership links to sanctioned individuals prosecuted for major crimes, including bank fraud, and repeated CA findings of misinformation, especially about Ukraine. Independent media organizations argued the evidence was insufficient to justify such restrictive measures, invoking a Constitutional Court decision (Republic of Moldova 2020) on emergency powers during the pandemic. The Court had stressed that emergency measures must remain necessary, proportional and under effective parliamentary control. On this basis, CSOs concluded that the ESC exceeded its mandate.

Enabler 15. Gaps in media and Internet regulations

Despite many improvements, national legislation still lags behind EU standards, particularly as audiences shift online and social networks expand. New provisions are required regarding media services, including traditional audio-visual and online outlets, stronger transparency rules on ownership and financing, extended source-protection guarantees and clear regulation of online influencers. Currently, authorities are working towards improving the governance of the online space, with several amendments being submitted to the Venice Commission (VC) for feedback.

At the 2024 Mass-Media Forum, journalists, CSOs and officials agreed that Moldova’s media legislation must be aligned with EU standards and revised to reflect the shift to online platforms (Media Azi 2024b). Priorities include adopting a new law on media services covering traditional, audio-visual and online outlets; ensuring transparency of ownership, financial activity and financial support; strengthening protections for information sources; and regulating online influencers.

Between December 2024 and May 2025, experts and the parliamentary committee drafted several laws, three of which, partly addressing the online environment, were sent to the VC for review (Council of Europe 2025). The authors of the drafts considered it ineffective to regulate digital platforms through a separate regulatory act, preferring to integrate the regulations into the Audiovisual Media Services Code to ensure legal coherence and uniform application of the rules. They insisted on ensuring transparency mechanisms and not on tightening sanctions to guarantee freedom of expression. A certain degree of consensus was also reached that more in-depth regulations for the online domain will become applicable after the standards in this regard are developed at the EU level.

These ongoing debates about reforming the media and Internet regulatory frameworks stem from the vulnerabilities of Moldova’s media and electoral context which became particularly visible during the 2023 and 2024 election campaigns. Legal and regulatory loopholes enabled foreign influence, and while extraordinary measures such as ESC interventions helped contain the immediate effects, they also harmed the government’s image. Currently, the draft laws submitted to the VC place greater emphasis on strengthening transparency of ownership and financing of online media providers, alongside fostering dialogue with major online platforms to counter disinformation and illegal funding.

Enabler 16. Unclear applicability of international norms

Public discussions on the need to develop a national and international legal framework to combat foreign interference took place on various TV channels, especially after the presidential elections in November 2024 in Romania. The interest in such debates is understandable, since (a) approximately one third of Moldovan citizens also hold Romanian citizenship; (b) Romania became the first country in Europe to annul election results due to alleged foreign interference; and (c) the Republic of Moldova itself was subjected to foreign interference in the recent presidential elections and on the eve of parliamentary election campaigns. The interest in debating the topic arose against the background of debates in the European Parliament on the impact the information platforms had on the election results in Romania (Grădinaru 2024) and also based on a report by Romanian non-governmental organizations (NGOs) (Expert Forum 2024). The most frequent issues discussed were the need to communicate with major digital platforms about moderation algorithms and regulations, and countering disinformation through monitoring, especially in electoral campaigns.

Incentive 1. Engagement-driven media business model

Moldovan media operate in a narrow advertising market that drives intense competition for attention, especially in the online space. This environment often favours cheaper, fast, short-form and sometimes slightly sensational content, though long-form journalism and investigative reporting are still present. Even if some engagement-driven practices can inadvertently aid disinformation, they are not widespread, partly thanks to the influence of international donor funding that has helped consolidate editorial independence over the years and increase the quality of Moldovan journalism. Many mainstream outlets also apply strict advertising policies to prevent manipulation and reject clickbait or opaque advertisements and dubious sponsors. Still, there have been instances when FIMI actors have exploited fringe platforms outside the formal media economy, such as pirated streaming sites, or by tapping into sites with high traffic and weak oversight to conduct disinformation campaigns.

Moldovan media operate under structural constraints, most notably a small advertising market and a limited audience. This fosters intense competition for public attention, especially among online outlets, encouraging a focus on speed and visibility. Common practices include publishing very short news and breaking news pieces with little depth, as well as using mildly sensationalist headlines to boost engagement. Such competition can lead to inadvertent complicity in manipulation. Long-form journalism exists but is under-represented. Although major outlets do produce investigative reports and in-depth analyses, experts note a scarcity, especially in specialized areas like economic reporting. Simpler formats remain more attractive and cheaper to produce. Journalists often justify these tendencies as pragmatic responses to commercial pressures, aimed at securing advertising and staying relevant in a crowded information space.

Interviewed stakeholders note that engagement-driven practices (such as sensationalism and click bait) remain the exception rather than the rule. Despite economic difficulties, they are not a defining feature of Moldovan media, nor do they create systematic vulnerabilities easily exploitable by FIMI actors. One explanation is the role of international donors: many mainstream outlets depend on Western grants and media development programmes which promote editorial independence, transparency and public-interest reporting. This support counterbalances commercial pressures, discourages clickbait and reduces the risk of covert advertisements. In this sense, donor dependence, often referred to as a sign of poor financial sustainability, may also be seen as a stabilizing element that sustains minimal quality and integrity standards across the media sector.

According to representatives of mainstream online media, some of these outlets have dedicated policies controlling the advertising they accept, which helps prevent the spread of harmful or manipulative content from unidentified sources. By contrast, less accountable platforms outside the formal media economy often lack such standards and are more attractive for FIMI actors. A notable example is the use of pirated movie streaming websites, reportedly of Russian origin, for disinformation in 2024. These sites carried video ads fabricating claims about EU-supported military training camps for Moldovan youth and a ‘patriotic tax’ on remittances (Vocea Basarabiei 2024). Both narratives played on fears of war, militarization and diaspora support, aiming to further erode trust in state institutions. The use of high-traffic entertainment platforms illustrates a deliberate strategy to exploit engagement-driven spaces beyond editorial oversight.

Incentive 2. The online political advertising market

Online political advertising has become a central feature of electoral campaigns in Moldova, mirroring global trends, with the 2024 presidential elections and constitutional referendum marking the most digital campaigns to date. In spite of that, Moldova’s regulatory framework lacks specific provisions for online political advertising and does not assign clear monitoring responsibilities. This leaves Moldova’s online ecosystem highly susceptible to foreign information manipulation and interference during elections.

Spending on online political advertising is rising globally (Heinmaa et al. 2023), and Moldova follows this trend. As Internet use for news and entertainment grows, online promotion has become central to electoral campaigns (Andronic 2024). A Promo-LEX monitoring report (2025b) shows that the 2024 presidential elections and constitutional referendum were the most digital electoral exercises to date, with about 35 per cent of observed campaign activities conducted online via Facebook, Google ads and promoted videos. Electoral competitors’ reported spending reached around MDL 5 million (USD 290,000), led by the Party of Action and Solidarity and Maia Sandu (36 per cent), followed by Renato Usatîi (11 per cent) and Alexandr Stoianoglo (8 per cent).

Alongside legitimate advertising, the 2024 electoral cycle exposed misconduct by Moldovan political actors and the strategic use of online advertising by FIMI-linked networks. Promo-LEX estimated that over MDL 400,000 (USD 23,000) in online ad spending went undeclared (Promo-LEX 2025a), while candidates such as Tudor Ulianovschi, Natalia Morari and Irina Vlah promoted ads before official registration, bypassing legal timelines. Beyond these violations, third-party actors exploited anonymous pages and fake accounts, obscuring attribution and financing. Monitoring by CSOs and journalists identified fugitive oligarchs Ilan Shor and Veaceslav Platon as key figures behind extensive disinformation operations (TVR Moldova 2025).

At present the Moldovan institutional and legal framework does not adequately address these issues (Realitatea.md 2025). Current electoral legislation lacks clear, enforceable rules for online political advertising, nor does it assign direct monitoring responsibilities to any single regulatory body. While the CEC and CA exercise general oversight, their capacity to track and sanction online activity is limited, especially with regard to opaque or foreign-based platforms. Global platforms are also inconsistent in their enforcement (Bouchaud, Faddoul and Çetin 2024): Meta’s ad library offers partial transparency, but often fails to identify the true funders, while Google and TikTok offer little to no public visibility into political ad spending in Moldova. Findings from International IDEA’s monitoring also highlight Moldova-specific blind spots: Google provided only minimal data on ad buyers, limiting accountability, while both candidates and third-party actors continued running ads during silence days, exploiting legal loopholes and platform inaction (International IDEA 2024).

This mix of weak legislation, limited platform accountability and low entry costs leaves Moldova’s online advertising environment especially vulnerable to FIMI during elections.

Incentive 3. Weaponization of foreign media funding

While overt foreign weaponization of media funding in Moldova has declined, structural vulnerabilities discussed earlier continue to expose the media sector to risks of influence and manipulation. Historical tactics have included covert payments, disguised ownership and content syndication to promote foreign agendas, particularly by Russian-linked entities. New challenges have also emerged in the online sphere, where unauthorized content reproduction and the shift of audiences to platforms like Telegram and TikTok further erode revenue potential. With FIMI threats intensifying ahead of elections, Moldova’s media sector faces the critical task of achieving financial sustainability without compromising editorial independence, requiring regulatory improvements, market development and public trust building through credible, audience-centred journalism.

Blatant weaponization of media funding in Moldova is limited today, but several forms have been observed over past decades: direct funding or covert payments to buy editorial influence, manipulative content syndication and obscure ownership structures using offshore companies to mask foreign control. These practices exploit chronic vulnerabilities such as weak financial sustainability, opaque ownership and limited regulatory oversight. Recent developments have improved regulation and transparency, and the ban on Russian broadcasters has reduced overt manipulation in the audio-visual media realm. Yet Moldovan media still face fragile finances, heavy dependence on foreign donors and an underdeveloped advertising market, compounded by broader economic difficulties (Durnea 2025). This context leaves the sector exposed to FIMI.