Harnessing Artificial Intelligence to Enhance Political Finance Oversight

This report explores how artificial intelligence (AI) can be—and in some instances is being—employed by electoral management bodies (EMBs) to regulate and analyse political finance. EMBs are one of the core means by which to ensure electoral integrity, but across the world they also face significant constraints based on resource and capacity. AI offers a promising, but underutilized, solution to this. The automation of routine/manual tasks can free up much needed time, as well as allowing for faster and deeper analysis of donations and spending data—so improving EMBs’ monitoring and compliance functions.

The motivation for this report is to:

- increase understanding of how AI can be used by EMBs to regulate political financing;

- map the ways in which AI is currently being used by EMBs to regulate political financing;

- identify needs and opportunities of EMBs to embed AI in their political finance oversight work; and

- promote best practice in the use of AI by EMBs.

The aim is to identify opportunities for the application of AI tools in electoral processes, with particular reference to those EMBs that have some kind of oversight/purview over the political finance regime. Beyond this primary focus, a wider interest is developing a community of practice for applying AI to electoral processes and devising standards of best practices in support, such that any tools adopted uphold rather than undermine democratic systems. This is done by drawing together experiences of using machine learning and automation to better understand how it can be harnessed to deliver effective and trusted elections.

The findings in the report draw on two UK Research and Innovation (UKRI) funded projects via the Trustworthy Autonomous Systems Hub and Responsible AI UK. These projects have included experimenting with (and creating) AI tools to be applied to the UK Electoral Commission’s political finance online database, and an extensive engagement with EMBs and civil society organizations (CSOs) working in this space—through working groups and workshops over the past three years. Additionally, nine in-depth interviews were conducted with representatives from EMBs (in Australia, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Colombia, Finland, Lithuania, Mexico, Panama, the United Kingdom and Uruguay). The interviews helped in mapping current AI usage, identifying opportunities for automation and promoting best practices. Through this process, three case studies were identified and have been included in the report which illustrate the potential of AI adoption, alongside cases of actual use:

- The United Kingdom: exploring how optical character recognition (OCR) and natural language processing (NLP) can be used to automate invoice processing and flag non-compliance,

- Lithuania: implementing algorithmic tools to streamline financial reporting and detect duplications,

- Mexico: using AI tools for near real-time expense tracking, auditing of suppliers and internal data visualization for policy analysis.

Moving beyond these examples, the report highlights the ways in which AI can improve transparency, consolidate disparate data sets which hold information on political financing, and ultimately support CSO efforts to monitor political donations and spending. The report also reflects on the barriers to AI adoption which remain. These are chiefly in three areas: (a) resourcing; (b) digital literacy; and (c) trust.

The report concludes by reflecting on the principles that EMBs should embed when pursuing greater use of AI. It recommends that EMBs ensure any tools used are appropriate based on socio-political context; that the principle of the ‘human in the loop’ is maintained; and that adoption is communicated clearly (in language the public understands) and is articulated as standard practice across multiple sectors. It is argued that these principles provide a basis for consensus-building and further refinement among EMBs, politicians, civil society, academia and industry practitioners.

AI should never replace democratic oversight; it should rather enhance that oversight. If employed in this way, the proper employment of AI tools can have genuine value, which is something often overlooked in popular discourse. By improving various efficiencies within EMBs, AI has the potential to help build trust, fairness and accountability in societies across the democratic (and democratizing) world.

Politics is in flux. In many places—including some of the most well-established liberal democracies—the future of the democratic project itself is no longer a given. This has led many to consider the ways in which democracy might simply end (e.g. Levitsky and Ziblatt 2019; Mounk 2022; Russell, Renwick and James 2022). The argument commonly made is that democracies die in four stages—the fourth of which, ‘harm to the electoral system’, is the focus of this report:

- A breakdown in norms of political behaviour and standards.

- Disempowerment of the legislature, courts and/or regulators.

- A reduction of civil liberties and press freedoms.

- Harm to the integrity of the electoral system.

One way to secure electoral integrity is through effective oversight—regulated, in varying ways and to varying degrees, by EMBs. In both established and transitional democracies, these EMBs aim to deliver trusted elections such that citizens perceive them as being run fairly. A core means by which EMBs do this is through managing political finance.

Money is best described as the ‘fuel of party politics’ (Casal Bértoa et al. 2014: 356). Political finance is thus essential for the smooth running of a democracy, but it is also dangerous. It must be tightly regulated in order to prevent it from overwhelming the system and causing untold damage to wider perceptions of electoral integrity. Generally, different countries approach regulation through some combination of the following:

- Limiting donations and/or spending.

- Introducing transparency requirements around the reporting of donations and/or spending.

- Subsidizing political parties/candidates via either direct or indirect funding from the state.

- Sanctioning non-compliance.

Transparency in relation to political finance is one of the most important requisites to expose undue influence and conflicts of interest that could distort democratic processes (Falguera , Jones and Ohman 2014; Hamada and Agrawal 2025). It is often held to be the key to ensuring elections are free and fair, and seen to be so.

According to International IDEA’s Political Finance Database, in most countries across the world political parties (79 per cent) and candidates (67 per cent) are required to report on campaign finances, and in 64 per cent of countries this information is to be made public. Such requirements allow the general public and the EMBs to monitor fiscal information and assess whether rules are being broken—especially around limits to donations/spending and the receipt/use of state funds. In short, transparency promotes accountability and compliance by providing a disincentive for politicians to break the rules. Further, transparency is said to give citizens a better understanding of the political system and, in performing this educative function, to increase public confidence in democracy itself (International IDEA n.d.).

Integrity and anti-corruption

In its ideal form, transparency and accountability in a political finance system adheres to a simple formula posited by Robert Klitgaard (1988) for the prevention of corruption:

C = M + D – A

Corruption = Monopoly + Discretion – Accountability

This formula suggests that corruption tends to occur where somebody (or something) has monopoly power, discretion over how to use that power, and a lack of accountability if/when they misuse that power. Accountability in this framework, especially when applied to political finance, operates via transparency. It serves as a bulwark against the misuse of campaign funds, and is an invaluable tool for regulators, investigative journalists and citizens alike.

However, transparency does not always achieve this lofty goal, and recent work has pointed to a ‘transparency paradox’ whereby political finance reforms that introduce more transparency might lead to fewer instances of corruption, but at the same time increase citizen perceptions of it (Fisher 2015; Power 2020). This is alongside recent work in Argentina which suggests that transparency can increase trust in government, but only when brought to citizens in a way which is ‘more than providing information on a website’ (Alessandro et al. 2021: 9).

While concerns about the use of AI have been well covered in the popular media, and specifically about how it might subvert elections, the focus here is on harnessing that same power to reinforce the electoral and regulatory architecture in place. EMBs across the world are resource- and time-poor. There is strong evidence, from both comparative and single-country case work, that the capacity of an EMB (in terms of resource and staffing) has a positive effect on perceptions of electoral integrity (Clark 2017; Garnett 2019; Langford, Schiel and Wilson 2021). One of the primary benefits of AI is that it allows an organization to automate routine tasks that, when conducted manually, take up much of its capacity. AI can, in short, make data available a lot more quickly and provide more granular insight into that data.

This reflects a wider truth that we are often lost in a vast sea of data—and it can be hard for everyone involved to analyse, or even make sense of, the data provided by political parties and candidates. What follows is an attempt to better understand how AI tools can be used in such a way that they enhance the electoral oversight capacity of EMBs, and by association improve perceptions of electoral integrity.

Methodology

This report is the product of two UKRI-funded projects via the Engineering and Physical Sciences Research Council. The first, from the Trustworthy Autonomous Systems Hub, was aimed at using data provided to the UK Electoral Commission to develop specific automated tools in the UK context which sort and analyse data on political spending (Power and Dommett 2025). The second from Responsible AI UK was given to form an international partnership to better understand how AI tools are (and, more often than not, are not) being adopted in EMBs around the world.

As a part of this project, the authors partnered with International IDEA to produce this report, which stems from multiple meetings with stakeholders over the past three years, as well as nine detailed semi-structured interviews with representatives from EMBs from: Australia, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Colombia, Finland, Lithuania, Mexico, Panama, the United Kingdom and Uruguay. Given that some of our work stems from attendance at stakeholder meetings and discussions/attendance/ presentations at workshops—where other representatives from EMBs expressed opinions about AI adoption without explicit consent but may have indirectly formed a part of our thinking in this space—the authors have taken the decision to not directly quote any of the semi-structured interviews. Instead, the findings are presented as a series of discussion points, with three in-depth case studies with organizations that were engaged with to a greater degree. This, therefore, represents both how AI is being implemented in certain instances, and how it is envisaged to be used in the future.

The various models of electoral management in different countries are well covered in International IDEA’s handbook on Electoral Management Design, defined therein as organizations that are in charge of ‘managing some or all the elements that are essential for the conduct of elections’ (Catt et al. 2014: 5). The model followed, and the EMB’s structure, are two elements which are important for whether and how it has capacity to introduce AI tools into its work.

Each EMB will manage elections somewhat differently, and their roles/core elements (at the country or federal level) are usually given in primary legislation. Generally accepted functions include:

- Determining who is eligible to vote.

- Receiving (and checking/validating) nomination papers for parties and/or candidates wishing to participate in an election.

- Administering the election (inclusive of counting/tabulating votes).

EMBs are often tasked with a number of further roles:

- voter registration;

- voter education;

- districting (determining constituency boundaries);

- media monitoring;

- oversight/sanctioning of electoral code violations; and/or

- managing political finance information.

This report is geared towards those EMBs which have some regulatory competence over the political finance regime and how this can be enhanced through AI. As such, the discussion falls within the second list of ‘non-core’ EMBs functions, specifically, those related to managing political finance information. Clearly, however, this may also engage issues of the electoral code and overseeing compliance with it. If these functions are held by a different regulator (or other institution) or are managed by a parliamentary committee, the findings below may still be of interest.

For this report—as in other International IDEA publications (e.g. Juneja 2024)—the definition of AI systems used is the one given by the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development:

An AI system is a machine-based system that, for explicit or implicit objectives, infers, from the input it receives, how to generate outputs such as predictions, content, recommendations, or decisions that can influence physical or virtual environments. Different AI systems vary in their levels of autonomy and adaptiveness after deployment.

(OECD 2024: 4)

There are many complex methods, tools and terminologies that one encounters when engaging with AI. The simplest way to think about AI, though, is as an automated system that can conduct relatively mundane tasks at great speed. AI tools often rely on methods like NLP and machine learning, which in turn can be supervised or unsupervised. The most common AI tool—used by most of the population in most countries—is predictive text messaging services. These are, effectively, supervised machine learning tools which predict what word the user is likely to use next—based on general inferences, but also past behaviour of the user. In short, if we understand predictive text messaging, we can understand the parameters of how AI might be used for more effective electoral oversight. Other common applications of AI include chatbots or virtual assistants, search engine summaries and facial recognition software.

There is very little existing research which assesses how AI can benefit EMBs’ financial oversight capabilities, and this report, the first which takes a comprehensive view, aims to fill this gap. Academics who have mapped the extent to which AI has been—or is being—used by EMBs have suggested that ‘the electoral process—the time, place and manner of elections within democratic nations—is one of the few sectors in which there has been limited penetration of AI’ (Padmanabhan, Simoes and MacCarthaigh 2023). That said, International IDEA has covered in detail how else AI can be and is being used during in the electoral cycle (Juneja 2024). Potential AI use cases during the pre-electoral period include voter list management and polling booth location determination. During the electoral period itself, AI could be used in campaign and media monitoring and voter authentication. And in the post electoral period, AI has potential uses in analysing and reporting electoral results and in political finance consolidation.

For this report, while the most immediate opportunities have to do with analysing spending returns in the post-election period, it is foreseeable AI will be applied to political finance regulation at other points in the electoral cycle as well. For example, given that it already happens in other contexts, AI offers the genuine potential for near real-time analysis of election spending (and election spending violations) during the electoral phase. Likewise, AI might be used in the pre-electoral period, particularly in those countries which have detailed requirements concerning the release of donor information over a certain threshold. For example, AI could consolidate donor information given in slightly different formats.

This chapter is separated into two parts, the first outlines three case studies of countries that are at different stages of embedding AI into their oversight practices. The second section outlines wider roles that AI can play as a part of the general practice of EMBs regardless of regulatory purview.

Case studies

Beginning to experiment: The case of the UK

The UK Electoral Commission remains at a relatively early stage of its engagement with AI, in which many of the proposed solutions remain at the development or testing stage as opposed to implementation. Moreover, much of this testing is being conducted outside the EMB itself by the authors of this report (and wider collaborators).

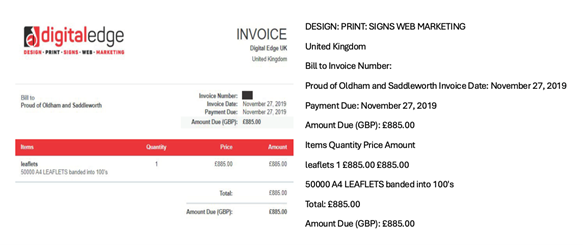

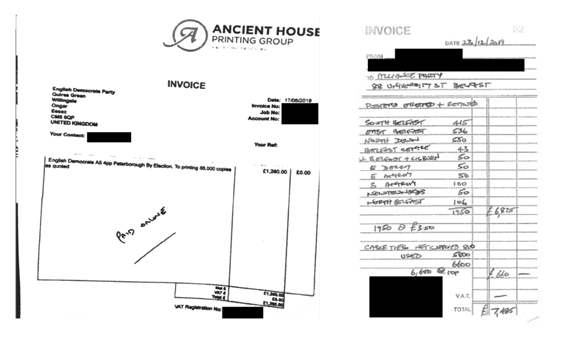

The UK political finance regime is based around two broad principles: limiting election spending, and increased transparency (see Power 2025a). While there is no limit to the amount a ‘permissible’ donor can give to UK political parties and/or candidates, there are limits to how much they can spend at elections and high-level itemization of election spending is required (see Power 2024). This means that after an election, spending is reported on the Commission’s political finance online database under nine categories (e.g. ‘media’, ‘overheads and general administration’, ‘rallies and other events’) alongside other details such as the name of the supplier. Additionally, all spending incurred over GBP 200 (USD 260) is also required to have an invoice or receipt attached with further information about the service being used.

There are a number of options for automation. Currently, Commission staff often have to rely on manual sorting of the data they receive from political parties/candidates, as there is no legal requirement for the latter to use an online submission system. This means that it can take up to a full year between an election occurring and full spending returns being released (see Power 2025b). Tools such as OCR and NLP could be used to effectively auto-scan and auto-sort the data based on training sets of common suppliers and common wording that feature in the invoices. Commission members could then monitor a certain number of returns to check the accuracy of the tool, as well as manually sorting those that are more difficult to machine read. This would also serve the purpose of spotlighting best practice in the reporting of said data and form the basis of templates for invoices that are easily machine-readable (see Figures 3.1 and 3.2).

OCR and NLP utilized alongside supervised machine learning can also serve as a ‘red flag’ system for non-compliance with disclosure requirements or other electoral laws. It might be the case that some information is incomplete which makes it hard or impossible for a machine to read. If the machine is struggling to read said information, it might be that it is either (a) not there; or (b) in the wrong format. A simple red flag system could operate to highlight potential issues of non-compliance for the EMB to investigate further.

If legislation were to require parties and candidates to use an online platform to submit spending returns, AI offers even further potential. Firstly, invoices could be instantly machine read and rejected if the necessary information is not computable, with a note requesting the information be resubmitted in a machine-readable format. If this is not possible, the user could be taken to a secondary platform in which the necessary information is submitted, alongside the invoice/receipt. This would create a significantly enhanced system allowing for near real-time reporting of electoral spending activity.

Employing AI tools: Lithuania

The Lithuanian Central Election Commission (CEC) represents a case of an EMB that has already adopted a range of algorithm-based tools for different purposes. They are particularly designed around the supply-side of the process and in making it easier and quicker for political parties to report on their financial activity. The principles behind Lithuania’s regulatory approach are based around transparency, whereby donations are disclosed at a very low level and are limited as a percentage of monthly earnings. A formula is also in place based on annual monthly earnings at the district level and extrapolated to form the spending limits for candidates. All donations must be disclosed to the CEC but they are only published if they are over EUR 50 in the case of a donation; or over EUR 360 if they are membership fees paid to a political party.

All of this financial activity is reported through the Political Parties and Political Campaign Financing Control Subsystem (VRK IS). To aid political parties/candidates on the back-end (i.e. in meeting their reporting obligations) the CEC has developed a range of algorithm-based tools for different purposes, from simple to more advanced. For example, for expenditure registration they have an algorithm which acts to auto-fill necessary information based on previously submitted banking and contact details. Given that membership fees are also tightly regulated based on average earnings, they also have a system which detects and reports duplications.

One concern among many in EMBs is that they do not wish to create unnecessary administrative burdens for electoral stakeholders. Improving these back-end systems in the way Lithuania has could point towards a carrot-and-stick approach that others might take. Put differently, more expectations could be placed on parties and candidates to report information in a standardized, digitized format—but in ways that are also user-friendly thanks to the use of algorithm-based tools.

The Lithuanian CEC is also pursuing other potential efficiencies. One such is the development of an AI-based tool for handling political campaign-related contracts/invoices of election spending. Currently, for example, contracts are reviewed manually to ensure bank and contact details are not included before they are made public via the VRK IS. The challenge here, as for many EMBs that were consulted for this report, is that contracts are not provided in a standardized format which makes it harder to apply OCR and more likely that privileged data could be inadvertently made public due to a machine-based error. If this information was required to be standardized, a model could be designed—relatively easily, especially if based around machine-readable best practice—which could auto-redact sensitive information.

Mexico: A case of well-embedded AI practice

Mexico is at the forefront of adopting AI tools into election oversight. The following is not an exhaustive summary of the Mexican EMB’s AI practices, but rather an outline of some of the tools adopted. This is partly out of necessity due to the wide scope of the oversight activities that fall under the purview of the National Electoral Institute (INE).

In Mexico, parties have to report election expenses in near real-time (every 72 hours), so the INE has developed models which have helped them to oversee compliance with this requirement. This includes a payroll tool, which helps them to identify all the transactions that are being carried out, which then auto-matches against party returns. The payroll tool thus allows for real-time analysis of reporting. Previously, this work was conducted manually by the staff and it was impossible to assess compliance as elections were happening.

A second system helps the INE to integrate all tax receipts that were issued by suppliers at elections and ensures that data/spending has been reported correctly. This tool, called Maria, cross-references the receipts against a national roll of service providers at elections and helps the INE to audit election spending returns. It works having been trained on data from prior elections stored on Excel files and has effectively created a databank of election-related suppliers.

Any country which has some form of election spending reporting requirement could do this and begin creating a bank of commonly used election suppliers and the services they provide (e.g. Meta = social media advertising). This would lead to quicker post-election analysis, aiding compliance work.

Thirdly, the INE has designed models for use within the organization which help staff to analyse the data that they receive. This includes programmes that create visualizations of data, and bots which they can use to interrogate and understand the input information. These programmes give the INE staff more time to analyse the data that they are receiving, as opposed to processing said data prior to the analysis.

Summary

The three cases reveal a spectrum of AI integration, each shaped by distinct regulatory contexts as well as varying levels of institutional capacity. The UK’s context demonstrates exploration, whereby methods such as OCR and NLP are being tested and refined with an eye to improving and streamlining post-election financial reporting, though actual implementation remains limited and largely external to the EMB. Lithuania has slightly more advanced systems in place which have embedded algorithmic tools to streamline financial reporting and reduce administrative burdens for political actors, while also exploring AI’s potential for contract redaction and compliance monitoring. Mexico is more of a leader in this space, with well-established systems that enable close to real-time oversight, auditing and sophisticated internal data analysis. Based on this, there are clear takeaways for those EMBs interested in adopting AI to a greater degree:

- Adoption should be scaled. Even modest experimentation, as seen in the UK, can and should lay the groundwork for more advanced use of AI technologies.

- Standardization is key. Requiring data in machine-readable formats makes it easier to unlock the potential of AI.

- AI should reduce administrative burdens and increase compliance. Well-designed AI tools can enhance transparency without adding to the administrative load on political parties and candidates - and can even lighten it. This is a win/win for the regulators, the regulated and wider publics.

- Real-time oversight is achievable. Early evidence from Mexico suggests that AI can move us closer to the goal of real-time monitoring of political finance.

From this, four recommendations are put forward:

- Invest in infrastructure. Begin with digitization and move towards a system of standardized accounting and reporting.

- Pilot AI use in low(er) risk areas. Using supervised machine learning for the auto-sorting of input data and red-flagging of non-compliance may build institutional confidence.

- Engage regulated communities. By co-designing tools which make it easier for political parties/candidates to comply, greater buy-in and user-friendliness is assured.

- Legislation matters. To aid real-time analysis, consider placing standardized accounting and online submission of financial data on a mandatory (statutory) footing.

Wider roles for AI in electoral management

International IDEA has conducted many studies on digital reporting and disclosure of political finance (see for example Jones 2017; Wolfs 2022; 2024; 2025). In particular, eight guiding principles on the public disclosure of financial data have been put forward (see Table 3.1). There are a number of examples of best practices (Wolfs 2022) in each of the eight areas highlighted in Table 3.1, which EMBs looking to overhaul their transparency efforts might use as inspiration. In all of these areas, AI tools will be of use.

| Overarching principles | Guiding principles | Best practice examples |

|---|---|---|

| Quality of information provided | 1. User-friendliness 2. Accessibility 3. Granularity (= depth) and comprehensiveness (= width) 4. Verifiability 5. Timeliness | 1. USA 2. UK, Norway, Finland 3. Lithuania, Norway (depth), Czechia (width) 4. Bulgaria 5. Mexico, USA |

| Quality of analytical practices | 6. Searchability 7. Comparability 8. Availability in bulk | 6. Lithuania, UK 7. Norway, Finland 8. Czechia |

For example, machine reading and NLP create opportunities for EMBs to gain a more granular and comprehensive insight into spending returns. Current legislation, more often than not, only specifies the minimum legal requirements for returns. However, more than minimum information is often provided, making manual assessment of returns costly and time consuming.

The UK is a good example of this. One of the authors of this report conducted a project, supported by International IDEA, wherein all invoices provided at the 2019 general election were manually coded to gain a better understanding (beyond the nine broad categories given in law) of what services were purchased at UK elections (see Dommett et al. 2022, 2025). This took two years for a research team of four to conduct. However, the insights gleaned from this analysis were then used to create training data and an AI tool which, when applied to the 2024 data, analysed the returns in under a week. Following this example, EMBs—absent of being empowered with new legislation—might use AI tools to conduct their own analysis and gain a better understanding how parties and candidates spend money at elections.

However, EMBs are often slightly constrained to the analysis of the data which is provided to them under law. CSOs, on the other hand, can benefit from (and use) the full range of publicly accessible data sources that exist, unencumbered by more stringent regulatory remits. There are numerous examples of ways in which CSOs (such as Who Targets Me and Open Secrets, see Box 3.1) use these publicly available data. This is often by using AI tools to scrape a variety of data sets in specific jurisdictions or comparatively. Often, data relevant to political spending and influence is held by different regulatory organizations, with different rules about what they can and cannot share. This can lead to situations where multiple data sets important for the regulatory community are not linked up and cannot speak to each other in meaningful ways. This can often be for perfectly legitimate reasons such as being compliant with national (and supra-national) data protection law.

Box 3.1. Civil society organizations mobilizing AI

Open Secrets: Making sense of messy data

Open Secrets is a non-profit organization based in the USA that aims to provide comprehensive and reliable data on money in politics (including lobbying) at both the federal and state levels. The main challenge it faces is that data inputs are incredibly messy. The same donor can often appear under different spellings, and companies can report names differently across multiple filings. The raw data, then, is often difficult to make sense of.

Open Secrets has spent over two decades building various tools which conduct automated ‘entity matching’. This automatically compares records, standardizes names and spotlights likely matches. It operates based on confidence intervals. When confidence is high, entities will be matched automatically, but in all other instances cases will be flagged for human review. It is a combination of automation with a human in the loop that maximizes efficiency while maintaining accuracy in more difficult cases.

Who Targets Me: Understanding how people see adverts online

Who Targets Me is a non-profit organization based in Ireland dedicated to monitoring online political advertising. They conduct a range of activities aimed at researchers, journalists, policymakers and other interested individuals. One main element of their work is a browser extension which volunteers install and ‘see’ the adverts that the user is exposed to on Facebook/Meta, Instagram, YouTube and X. The user can then see this information too, and it is used by Who Targets Me to conduct further research into online political advertising. A second workstream is a ‘Trends’ function, which tracks online ad spending, content and its targeting across (at time of publication) 53 countries.

Who Targets Me is also experimenting with using AI to tag adverts and advertisers by goal, with AI-produced summaries/analysis of ad content, inclusive of details about overall cost/spend. Much of the work, like that of Open Secrets, involves some automated classification, but with significant human oversight to ensure accuracy.

In these cases, AI can be used to consolidate much of this information in one place. For example, lobbying registers could be linked to other databases which collate politicians’ business interests, alongside political finance databases. This will help, in at least some ways, to gain a better understanding of elite networks and, for regulators, make it easier to spot problematic practices.

However, the experience of Open Secrets and Who Targets Me points to both the promise and limitations of using AI to better understand political finance data. AI offers users the ability to handle vast amounts of often discrete information which has, until now, been hard to analyse. AI tools in this area are very effective at highlighting patterns, flagging anomalies and bringing information together. However, both cases highlight the importance of maintaining a human in the loop, especially for interpreting borderline cases.

The many barriers to the use of AI by EMBs may be summarized under three main areas—resourcing, digital literacy skills and trust (internal and external).

Resourcing

One of the common challenges that EMBs face, as outlined in the introduction, is that they are resource- and time-poor. One of the benefits of AI is that it can provide staff within EMBs with more time to conduct other elements of their oversight practice. However, AI does not necessarily solve the problem of money and, at least in the short term, carries its own costs.

In particular, it is expensive to digitize an EMB. This involves a fundamental rethink of institutional architecture, and an embrace of digitization and the requisite tools. AI is also not a one-off expense, but an investment of time and resources. These tools are adaptive, which means that they need near-constant upkeep. Adopting AI also means hiring staff with the requisite skills, and a public sector organization will almost always lag behind the private sector in the pay it can offer.

Any adoption of new digital infrastructures opens up new potential for malign actors to conduct attacks. This is why some of the EMBs that were consulted discussed their conservatism (in the more general sense) regarding deeper engagement with digital and e-voting, for example. In terms of political financing, the more an EMB keeps data and databases on the cloud (publicly accessible or otherwise), the more that EMB leaves itself vulnerable to different kinds of cyber interference. Threat prevention, again, will likely involve significant and continued financial outlay.

Digital literacy

The problem of needing to employ new staff—with a new (and expensive) skill set—relates to a wider problem of digital literacy. Many AI-enabled practices within an EMB will require an understanding of how AI tools work, how to fix problems when they occur and how to understand complex inputs and outputs. There are likely few people working at EMBs with this kind of background and this kind of training.

One solution is to hire discrete AI divisions within an EMB, but this requires a huge financial investment. Another is to train existing staff, but this is both time consuming and expensive. A third option would be to work with outside organizations to either outsource the AI work entirely, or develop an exchange/secondment programme. This brings its own problems of what data can and cannot be shared with third parties—as well as wider questions of security and accountability. Relevant private companies may be global or foreign rather than national organizations and they may not share the same democratic instincts and motivations as the EMB, voters and other electoral stakeholders.

Trust

This relates to a third key issue: trust in AI systems themselves. Trust largely manifests in two ways, internally and externally. This means that EMBs will have to ask two basic questions when adopting AI tools:

- How can this earn and enhance trust among the general public?

- How can this earn and enhance trust among the staff and regulated community (electoral contestants, contractors)?

External trust

A recent Eurobarometer survey suggests that public confidence in AI is relatively high. Fifty-six per cent say that most recent technologies (which includes AI) have a positive impact on society, though a not insignificant amount (33 per cent) have a negative view about their impact (Eurobarometer 2025). Similarly, a UK government backed study reporting in 2024 suggested that the public believes ‘data use is beneficial to society’ but while ‘public attitudes regarding the value and transparency of data use are becoming more positive, concerns around accountability persist’ (Department for Science, Innovation and Technology 2024). In particular, the report highlights that the British public’s negative or fearful conceptions and associations regarding AI reflect concerns about its proliferation. Given this, one should be cautious about the extent to which decisions made by EMBs are outsourced to AI and AI alone.

It is simplistic to think of AI as either trusted or mistrusted by the public. AI is, rather, both trusted and mistrusted at the same time, dependent on the task and context. So, the question is not whether to use AI tools, but how best to communicate that AI tools are being used. If it is specifically pitched as being used in ways that are common in most workplaces (e.g. the completion of mundane tasks, and to improve efficiency), any public outcry is likely to be mediated. This is especially if analogies can be drawn with ways in which AI is currently in use, and accepted, across most of society. Returning to the Eurobarometer AI survey, and this time focusing on AI in the workplace, 66 per cent of respondents from across the EU positively perceive the impact of the use of AI on their job. On digging a little deeper into the data, it can also be seen that 73 per cent agree that AI increases the pace at which tasks can be completed and 66 per cent deem AI to be necessary to do jobs perceived as boring or repetitive.

Internal trust

The general public, of course, are not the only stakeholder for whom trust in AI tools is important. Those using the tools in day-to-day electoral work also need to buy-in to the benefit that they provide. In the interviews conducted for this report, there was a general acceptance that AI tools had a role to play in the future functioning of an EMB. At the same time, different questions of trust emerged. On the one hand, some reported that colleagues had a lack of trust in many of the proposed technological solutions, with some concerned that AI’s proliferation would cause them to lose their jobs. On the other, some reported colleagues placing excessive, uncritical trust in the outputs gathered using AI tools and not performing the requisite checks to assess accuracy. Both issues relate to technical dependency and institutional memory. Notwithstanding that some long-standing and long-held skills within an EMB may become obsolete, it is important that certain skills and knowledge are not lost, especially in case of some kind of cyber event which would require systems to move offline for a significant amount of time.

There was also variance on which areas of electoral management were considered to be appropriate for adoption of AI. While there was common agreement that AI would be an effective means to analyse political finance data, scan invoices and create semi-automated systems within areas of compliance work, differences were apparent too. For example, some of the EMBs were in favour of creating an EMB chatbot with which regulated stakeholders (and citizens) could interrogate surrounding aspects of electoral law (and compliance) as being of great benefit. Others, however, considered this to be an area that had been already discussed, but not pursued, primarily due to fears of malfunction (incorrect, hallucinated or nonsensical responses) inflicting reputational damage on the EMB’s brand or contravening electoral regulations. Elements of machine error were seen to be acceptable, particularly where human oversight would serve as a mediator. However, in the chatbot example—which would represent an entirely digitized tool—some respondents expressed deep concerns.

This reflects the wider issue that AI tools are not 100 per cent accurate and are unlikely to ever be so (though of course humans are also not infallible). Those working within EMBs should operate on this understanding and be sure that it underpins a ‘human in the loop’ philosophy of AI adoption. Those working at EMBs, if they adopt AI models, will also have to become comfortable with the fact that many AI tools—and especially those that use ‘deep learning’ models—are uninterpretable. In other words, it is not possible to know why the tool has given a particular output. Therefore, EMBs may need to consider the extent to which uninterpretable models are used, especially when it may be important to communicate both to the general public and to political parties and candidates why certain decisions have been made.

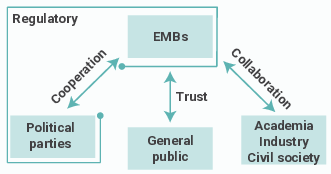

As with most elements of electoral regulation (and political finance regimes) there is no perfect system, or perfect use of AI. Effective uses will necessarily be underpinned by a clear understanding of the nexus of interconnected stakeholders central to the adoption of AI in electoral regulation. The effective and trusted implementation of AI is not a task for EMBs alone. It involves a complex interplay between regulators, the regulated community, the general public and external partners, as illustrated in Figure 5.1. Understanding these relationships is key to building a robust framework for AI in electoral oversight.

The nexus is constituted by four key groups. First, EMBs are at the core, as they are crucially involved in the planning, establishment and operation of AI-driven initiatives for more effective electoral management—each within a specific national regulatory context. Secondly, there are political parties. While parties are subject to regulations enforced by EMBs and the courts, they can also play a crucial role in the effective implementation of AI-based tools in electoral management. When an EMB implements a new AI-based tool to enhance efficiency, its efficacy is dependent on its use by political parties. As noted in the case of Lithuania, algorithm-based tools can significantly ease the reporting burden on parties, but such a ‘carrot’ approach works only if parties engage with the system in good faith and use the tools as intended.

Furthermore, the general public is a crucial component of this nexus, as their trust is essential for the legitimacy of AI-driven initiatives. This links back to the core issue of external trust: how the public perceives an EMB's use of AI has profound implications for their confidence in the democratic system itself. Therefore, communication about the process of developing and operating these initiatives needs to be handled with great care to pre-empt concerns and build public confidence. Finally, academia, industry and CSOs are further key stakeholders within the nexus. As previously noted, EMBs lack the capacity to innovate with AI technologies on their own. The expertise, skills and resources possessed by academic institutions, the technology industry and CSOs are indispensable. These groups could form a crucial support network, enabling EMBs to develop and operate complex AI-based tools for electoral oversight.

Understanding this nexus provides the foundation for establishing principles to guide the development of a system of best practice in electoral regulation. In place of clear templates of best practice, below a set of standards are outlined which might guide the adoption of AI in this space.

The human in the loop

Trust in democracy and democratic outputs is hard won but easily lost, and when lost is incredibly challenging to restore. Therefore, at every stage, the uses of AI should be guided by intention to maintain trust and support the work of democratic oversight bodies/EMBs. To this end, human oversight is essential when employing AI tools such that AI enhances and does not replace our systems of electoral oversight. We should therefore think about ways in which AI can help to process vast swathes of data, and its power to conduct (often) rudimentary analytical tasks. AI systems should not, however, be the sole arbiter of decisions about malpractice; instead they should raise red flags for further (human) investigation.

Indeed, we should be guided by machine learning methods for the adoption of AI tools. Unsupervised machine learning is where training data remains unlabelled, and a model finds patterns in specific subsets of data. But supervised machine learning involves a certain amount of human oversight, whereby training data sets are annotated and labelled with the aim that a model better matches certain inputs with specific outputs. We should follow, where possible, a philosophy of supervised machine learning/AI adoption—especially when creating public-facing tools or making decisions that relate to potential instances of non-compliance with electoral law.

Always be driven by context

This report outlines a number of examples of how AI either is or might be used in specific regulatory settings. These can, and should, serve as useful guides and templates. However, when adopting AI important discussions need to be had about regulatory context (so that AI solutions are useful for specific contexts) and about wider societal norms (so AI tools are more likely to be trusted by the public and users alike). These discussions are likely to be already ongoing in most cases and contexts, but should form a continuous part of the process of AI adoption.

At the very minimum, EMBs should establish AI working groups which meet regularly to experiment with different ways in which AI might be employed and review the effectiveness (or otherwise) of different tools. This can often be done with off-the-shelf packages like ChatGPT, Gemini and Co-pilot and can involve everything from experimentation with summarizing documents/meeting transcripts to the analysis of data inputs. An initial guiding question for these groups should be, ‘What do we spend a lot of our time doing, which would be better spent elsewhere?’

Collaboration will be key

The report outlines the three main barriers to the successful adoption of AI tools—resourcing, digital literacy skills and trust. It also covers ways in which issues of trust can be mitigated. To manage issues related to skills and resourcing, deeper collaborations will be necessary. This includes but is not limited to those working in: government, electoral management, civil society, industry and academia. In particular, EMBs should focus on deepening collaborations with industry and academia to achieve their goals.

While there may be some squeamishness around mixing institutions designed to protect democracy with private (global) companies which may not always share the same democratic ideals, it should be understood as an uncomfortable necessity. These organizations will always be able to fiscally outmanoeuvre public sector bodies which means that recruitment and retention of staff with requisite data skills will be a challenge. Therefore, EMBs might explore deeper collaboration with certain industry partners where those willing (such as Microsoft) share examples of best practice, but perhaps even in the development of projects which embed AI practice within the EMB itself.

Likewise, there is much expertise in the field of academia which has been hitherto underutilized. In many countries, the incentive structures built around academia have changed such that an engagement with real-world policy impact is encouraged (as opposed to being held as something to be somewhat wary of). There are, therefore, many academics who are able to share expertise, initial models and tools, and specific approaches. Efforts should be redoubled to identify existing expertise in the field and pursue the potential for active collaboration through academic fellowships and other means.

Finally, it should be noted that many CSOs across the world have utilized AI tools to gain a better understanding of the nature of political financing and money in politics more broadly, in specific cases and contexts. These tools are often run on a relative shoestring, through increasingly inventive means. Where this is not already happening, CSOs should be invited to share expertise and be involved in establishing AI models and tools.

The challenges that AI presents to the future of democracy and to societies in general have been the focus of much analysis in recent years. And yet, one space in which AI and its potential benefits are underdeveloped is in protecting democracy. In a rapidly changing and volatile political world, this is an oversight. While conversations have begun, and progress has been made in 2024–2025, these efforts remain in their infancy. As a further impetus for EMBs worldwide to engage and adopt AI tools as a part of their regulatory practices, below are summary recommendations aimed at managing the barriers to AI adoption outlined above.

- Human in the loop. AI tools should support, not replace, human oversight. Use supervised learning models and ensure manual review of flagged anomalies. Avoid over-reliance on fully automated (unsupervised) autonomous systems.

- Contextualize AI adoption. Tailor AI tools to the specific legal, institutional and cultural context each EMB works in. Establish internal working groups to explore potential applications. Frame AI usage in terms the public understand, are familiar with and support (e.g. in terms of improving efficiency and automation of manual tasks).

- Embrace collaboration. Partner with academia, CSOs and industry to access expertise, share resources and co-create tools. Consider fellowships and secondments to this end. All partnerships with private companies should be fully transparent and protect EMB independence as a standard.

- Spotlight strengths. Currently AI holds much potential to enhance the granularity, timeliness and accessibility of political finance information.

- Support regulated communities (electoral contestants and contractors). AI tools can, and should, ease the reporting burden on political parties and candidates. To achieve this, encourage standardized accounting and digital submission portals.

- Financial sustainability. AI adoption requires ongoing investment in digital infrastructure and skills. Budget accordingly and seek external support where appropriate.

AI continues to evolve at a rapid pace, and its implications for political finance oversight and elections will undoubtedly extend far beyond what this report can capture today. Importantly, the impact of AI is not confined to longer established democracies; it also poses significant opportunities and challenges for lower-capacity institutions and transitional democracies across the Global South. Advancing research, promoting knowledge exchange, and strengthening technical cooperation between experts and international organizations in this field should therefore be treated as a high priority in the years ahead.

Alessandro, M., Lagomarsino, B. C., Scartascini, C., Streb, J. and Torrealday, J., ‘Transparency and trust in government: Evidence from a survey experiment’, World Development, 138 (2021), pp. 1–18, <https://doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2020.105223>

Casal Bértoa, F., Molenaar, F., Piccio, D. R. and Rashkova, E. R., ‘The world upside down: Delegitimising political finance regulation’, International Political Science Review, 35/3 (2014), pp. 355–75, <https://doi.org/10.1177/0192512114523302>

Catt, H., Ellis, A., Maley, M., Wall, A. and Wolf, P., Electoral Management Design, Revised Edition (Stockholm: International IDEA, 2014), <https://www.idea.int/publications/catalogue/electoral-management-design-revised-edition>, accessed 10 December 2025

Clark, A., ‘Identifying the determinants of electoral integrity and administration in advanced democracies: The case of Britain’, European Political Science Review, 9/3 (2017), pp. 471–92, <https://doi.org/10.1017/S1755773916000060>

Department for Science, Innovation and Technology, ‘Public Attitudes to Data and AI: Tracker Survey (Wave 4) Report’, UK Government, 16 December 2024, <https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/public-attitudes-to-data-and-ai-tracker-survey-wave-4/public-attitudes-to-data-and-ai-tracker-survey-wave-4-report>, accessed 3 November 2025

Dommett, K., Power, S., Macintyre, A. and Barclay, A., Regulating the Business of Election Campaigns: Financial Transparency in the Influence Ecosystem in the United Kingdom (Stockholm: International IDEA, 2022), <https://doi.org/10.31752/idea.2022.28>

Dommett, K., Power, S., Barclay, A. and Macintyre, A., ‘Understanding the modern election campaign: Analysing campaign eras through financial transparency disclosures at the 2019 UK general election’, Government and Opposition, 60/1 (2025), pp. 141–67, <https://doi.org/10.1017/gov.2024.3>

Eurobarometer, Artificial Intelligence and the Future of Work (Brussels: European Commission, 2025), <https://europa.eu/eurobarometer/surveys/detail/3222>, accessed 3 November 2025

Falguera, E., Jones, S. and Ohman, M., Funding of Political Parties and Election Campaigns: A Handbook on Political Finance (Stockholm: International IDEA, 2014), <https://www.idea.int/publications/catalogue/funding-political-parties-and-election-campaigns-handbook-political-finance>, accessed 3 November 2025

Fisher, J., ‘Britain’s stop-go approach to party finance reform’, in R. Boatright (ed.), The Deregulatory Moment? A Comparative Perspective on Changing Campaign Finance Laws (Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 2015)

Garnett, H. A., ‘Evaluating electoral management body capacity’, International Political Science Review, 40/3 (2019), pp. 335–53, <https://doi.org/10.1177/0192512119832924>

Hamada, Y. and Agrawal, K., Combatting Corruption in Political Finance: Global Trends, Challenges and Solutions (Stockholm: International IDEA, 2025), <https://doi.org/10.31752/idea.2025.8>

International IDEA, Political Finance Database, [n.d.], <https://www.idea.int/data-tools/data/political-finance-database>, accessed 3 November 2025

Jones, S., Digital Solutions for Political Finance Reporting and Disclosure: A Practical Guide (Stockholm: International IDEA, 2017), <https://www.idea.int/publications/catalogue/digital-solutions-political-finance-reporting-and-disclosure-practical-guide>, accessed 3 November 2025

Juneja, P., Artificial Intelligence for Electoral Management (Stockholm: International IDEA, 2024), <https://doi.org/10.31752/idea.2024.31>

Klitgaard, R., Controlling Corruption (Los Angeles: University of California Press, 1988)

Langford, M., Schiel, R. and Wilson, B. M., ‘The rise of electoral management bodies: Diffusion and effects’, Asian Journal of Comparative Law, 16/S1 (2021), pp. 60–84, <https://doi.org/10.1017/asjcl.2021.29>

Levitsky, S. and Ziblatt, D., How Democracies Die: What History Reveals About Our Future (London: Penguin, 2019)

Mounk, Y., The Great Experiment: Why Diverse Democracies Fall Apart and How They Can Endure (London: Penguin, 2022)

Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), ‘Explanatory Memorandum on the Updated OECD Definition of an AI System’, OECD Artificial Intelligence Papers No. 8, March 2024, <https://www.oecd.org/content/dam/oecd/en/publications/reports/2024/03/explanatory-memorandum-on-the-updated-oecd-definition-of-an-ai-system_3c815e51/623da898-en.pdf>, accessed 3 November 2025

Padmanabhan, D., Simoes, S. and MacCarthaigh, M., ‘AI and core electoral processes: Mapping the horizons’, AI Magazine, 44/3 (2023), pp. 218–39, <https://doi.org/10.1002/aaai.12105>

Power, S., ‘The transparency paradox: Why transparency alone will not improve campaign regulations’, Political Quarterly, 91/4 (2020), pp. 731–38, <https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-923X.12886>

—, Keeping Up with Political Finance in the Digital Age in Albania: Prospects for Greater Regulation and Transparency (Stockholm: International IDEA, 2024), <https://doi.org/10.31752/idea.2024.11>

—, ‘If not now, when? The case for urgent reform of the UK’s political finance laws’, Political Insight, 16/1 (2025a), pp. 36–39, <https://doi.org/10.1177/20419058251332345>

—, ‘Party spending in the 2024 UK general election’, 7 August 2025b, <https://commonslibrary.parliament.uk/party-spending-in-the-2024-general-election>, accessed 3 November 2025

Power, S. and Dommett, K., ‘Why Labour’s elections bill misses the point’, Political Insight, 16/3 (2025), pp. 28–30, <https://doi.org/10.1177/20419058251376782>

Russell, M., Renwick, A. and James, L., ‘What is democratic backsliding, and is the UK at risk?’, UCL Constitution Unit Briefing, July 2022, <https://www.ucl.ac.uk/social-historical-sciences/sites/social_historical_sciences/files/backsliding_-_final_1.pdf>, accessed 3 November 2025

Wolfs, W., Models of Digital Reporting and Disclosure of Political Finance: Latest Trends and Best Practices to Support Albania (Stockholm: International IDEA, 2022), <https://doi.org/10.31752/idea.2022.40>

—, Political Finance in the Digital Age: A Case Study of the European Union (Stockholm: International IDEA, 2024), <https://doi.org/10.31752/idea.2024.26>

—, Political Finance in the Digital Age: Towards Evidence-Based Reforms (Stockholm: International IDEA, 2025), <https://doi.org/10.31752/idea.2025.28>

Sam Power, PhD, is a lecturer in Politics at the University of Bristol and a leading expert in political financing, electoral regulation and corruption. His work on the use of AI in elections and political finance has been funded by UK Research and Innovation’s Trustworthy Autonomous Systems Hub and Responsible AI UK. He is an experienced public speaker, media commentator and consultant and is currently a parliamentary academic fellow at the UK House of Commons.

Gilsun Jeong, PhD, is a political scientist and leading expert in EU politics and computation text analysis, currently based at the University of Nottingham. He served as a research associate in AI and politics on the Responsible AI UK project Harnessing AI to Enhance Electoral Oversight.

Abbreviations

| AI | Artificial intelligence |

|---|---|

| CEC | Central Election Commission, Lithuania |

| CSO | Civil society organization |

| EMB | Electoral management body |

| INE | National Electoral Institute, Mexico |

| NLP | Natural language processing |

| OCR | Optical character recognition |

| UKRI | UK Research and Innovation |

| VRK IS | Political Parties and Political Campaign Financing Control Subsystem, Lithuania |

This research project was carried out on behalf of, and in collaboration with, a wider research team—without whom it would not have been possible: Professor Katharine Dommett, Dr Safia Kanwal, Dr Judita Preiss and Professor Adam Sheingate.

We are also grateful to those who attended the workshops in Washington, DC (2024) and at Johns Hopkins University (2025); and to Khushbu Agrawal, Alberto Fernandez Gibaja, Katarzyna Gardapkhadze and Yukihiko Hamada for their careful review and thoughtful comments on the various drafts of this report. Thanks also to Lisa Hagman for leading the publication process.

This work was supported by the Engineering and Physical Sciences Research Council [grant number EP/Y009800/1] through funding from Responsible AI UK.

© 2026 International Institute for Democracy and Electoral Assistance

International IDEA publications are independent of specific national or political interests. Views expressed in this publication do not necessarily represent the views of International IDEA, its Board or its Council members.

With the exception of any third-party images and photos, the electronic version of this publication is available under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 (CC BY-NC-SA 4.0) licence. You are free to copy, distribute and transmit the publication as well as to remix and adapt it, provided it is only for non-commercial purposes, that you appropriately attribute the publication, and that you distribute it under an identical licence. For more information visit the Creative Commons website: <http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/4.0>.

Design and layout: International IDEA

Cover illustration: AI large language models by Wes Cockx & Google DeepMind, <betterimagesofai.org>, CCL BY 4.0

DOI: <https://doi.org/10.31752/59539>

ISBN: 978-91-8137-095-9 (HTML)

ISBN: 978-91-8137-094-2 (PDF)