Enablers and Incentives of Election-Related Foreign Information Manipulation and Interference in North Macedonia

North Macedonia is a notable case study for better understanding how vulnerabilities within a country’s democratic, media and social systems can be exploited by foreign information manipulation and interference (FIMI) actors both domestic and foreign. Despite its formal commitment to democratic reforms and regular elections, the country’s institutions remain fragile and often subject to political pressure. Unclear financing and inconsistent regulatory enforcement are exacerbated by deep political polarization and mistrust, ethnic divisions and fragmented public discourse. The latter challenges manifest—and are amplified by—exclusionary narratives, often with the involvement of FIMI actors’ domestic proxies.

The country’s political institutions, while formally grounded in separation of powers and periodic competitive elections, remain vulnerable to systemic corruption, partisan media coverage and ineffective enforcement of campaign finance rules. Ethnic power-sharing arrangements, though stabilizing, have institutionalized clientelism and weakened accountability. These vulnerabilities are compounded by ongoing challenges such as politicized judicial systems and recurring governmental crises. It is worth noting that North Macedonia has taken positive steps in electoral reform, civil society mobilization and European Union-aligned policy commitments. However, while the EU integration process and a vibrant civil society offer some measure of protection, foreign actors continue to exploit ethnic tensions and scepticism towards Euro–Atlantic integration through coordinated disinformation campaigns.

Regulation of North Macedonia’s political finance system, governed by laws on party financing and electoral conduct, suffers significant shortcomings in both scope and implementation. Particularly in the context of online campaigning and use of influencers in political communications, this has left the system open to abuse and interference. The lack of stringent disclosure requirements for digital campaign funding makes it difficult to trace financial flows or detect foreign-sponsored influence operations.

FIMI campaigns weaponize North Macedonia’s social, political and cultural divisions, with gender and minority rights increasingly targeted as subjects of disinformation. Narratives hostile to human rights—often coordinated with religious institutions and amplified by foreign-aligned media—seek to erode democratic participation, delegitimize public institutions and polarize society. Public discourse is already highly polarized, with debates over national identity, ethnic relations and EU integration routinely framed in exclusionary and antagonistic terms.

The news media ecosystem, while outwardly pluralistic, is fundamentally imbalanced. Ownership is highly concentrated, journalistic standards are low, and many outlets are economically dependent on political actors. The dominance of a few media narratives, combined with weak regulatory enforcement and limited journalistic resources, has led to the prevalence of ‘copy-paste journalism’. Sensationalism and engagement have tended to win over integrity, creating fertile ground for the rapid spread of disinformation. As a result, public confidence and trust in mainstream news sources has declined, with many citizens turning to personal contacts or non-traditional information sources.

Foreign-aligned narratives—particularly those aligned with Chinese, Russian and Serbian interests—are pervasive, and target linguistic, cultural and political fault lines. These coordinated campaigns often interact with local economic incentives, as unregulated content farms and so-called ‘phantom media’ outlets monetize polarizing content. By quickly adapting to regulatory and technological shifts, the North Macedonian FIMI industry has played a role in disinformation globally—most notably during the 2016 United States election.

Lacking effective moderation, digital and social media platforms have become primary vectors for the spread of divisive disinformation content. High Internet penetration rates, unmatched by digital literacy, leave large segments of the population susceptible to manipulation. The regulatory and legal framework remains fragmented and underdeveloped, with ineffective oversight and unclear applicability of international norms. At least five parliamentary committees have a mandate to address FIMI issues but only the Defence and Security Committee has so far begun to engage.

Civil society organizations play a crucial role in countering FIMI and have made some progress in raising awareness and advocating for transparency, media literacy and institutional reforms. However, in the absence of a coordinated national response and sustained political will, their efforts remain insufficient and fragmentary. As North Macedonia pursues Euro–Atlantic integration, the stakes are high: the country’s ability to build resilience against information manipulation will not only shape its democratic future but also serve as a critical example for the wider region.

Box 0.1. Country context

North Macedonia is a small, multi-ethnic country in the Balkans which gained its independence in 1991 (then named Former Yugoslav Republic of Macedonia). In the 2021 census, the population was around 1.84 million. For the last combined parliamentary and presidential elections in 2024, there were 1,815,350 registered voters (International Foundation for Electoral Systems 2024). The official language is Macedonian, with Albanian being widely spoken and officially recognized in many municipalities; other minority languages so recognized include Romani, Serbian and Turkish. North Macedonia has a multiparty political system, with numerous political parties represented in its unicameral parliament, the Sobranie, which currently has 120 seats. Parliamentary elections use a proportional representation system with closed party lists and are held every four years—the next general election is scheduled for 2028. Local elections are due to take place in October 2025.

It is safe to say that over the past decade, North Macedonia has demonstrated how domestic vulnerabilities can be exploited through foreign information manipulation and interference (FIMI). Since becoming an independent state in 1991, when the country ceased to be part of the Socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia, it has faced multiple challenges related to political polarization, ethnic divisions and trust in public institutions. This has created fertile ground for influence operations that target the country’s democratic processes and social cohesion.

This report examines the information environment in North Macedonia as it prepares for local elections in October 2025, with a focus on FIMI. Drawing on the country’s recent history of disinformation and institutional fragility, the analysis explores how digital platforms, weak media regulation and partisan dynamics create democratic vulnerabilities.

Specifically, the report concentrates on the mechanisms through which disinformation spreads, the structural and political enablers and incentives of these dynamics, and the consequences for democratic resilience. In doing so, it assesses the role of civil society, regulatory institutions and political actors in either enabling or mitigating the impact of FIMI. Special attention is given to the intersection of ethnic tensions, digital campaigning and economic incentives shaping the media landscape.

North Macedonia’s experiences of FIMI do not occur in a vacuum. As a small, multi-ethnic state navigating Euro–Atlantic integration, its struggles with disinformation reflect broader regional and global trends. It is crucially important to understand these dynamics and to identify potential ways to mitigate the malign effects, not just because of the upcoming elections, but also for informing long-term strategies to counter FIMI in fragile democracies.

Methodology

This report is grounded in the global methodology Analysing Enablers and Incentives of Election-Related Foreign Information Manipulation and Interference, developed by International IDEA (Giulio Sicurella and Morača 2025), adapted to the specific political, social and media landscape of North Macedonia.

The structure of the report follows a thematic approach. It first explores the enablers of FIMI—loosely defined as the social, political, institutional and technological conditions that allow FIMI to take root and spread. These include systemic vulnerabilities such as weak democratic institutions, divisive political discourse, media partisanship and gaps in regulatory frameworks.

Next, the report examines the incentives for FIMI, understood as the reasons FIMI actors find it profitable or strategically beneficial to interfere in election-related information environments. These range from financial and political gains in the attention economy to access to foreign-sourced resources and influence networks.

Finally, the report offers a forward-looking section with concrete recommendations for action. These are intended for various stakeholders—including civil society, media actors, regulatory bodies and international partners—with the aim of supporting the development of resilient, context-sensitive responses to FIMI threats.

The report was developed using a combination of primary and secondary sources including original research and analyses from the Metamorphosis Foundation, reports and data from various news organizations, and secondary sources from the European Commission and other relevant institutions. The analysis, conducted in April–May 2025, reviewed the state of election-related FIMI in North Macedonia over the previous five years.

1.1. Institutional vulnerabilities

North Macedonia is a parliamentary democracy with a multiparty system, formally grounded in the separation of powers and periodic competitive elections. Its democratic institutions remain less than resilient, shaped by enduring political polarization, ethnic divisions and systemic corruption.

According to a recent European Commission country report, while elections are generally well organized, serious concerns persist including credible allegations of political pressure, deficiencies in campaign finance transparency, and misuse of public resources which undermine trust in the democratic process (European Commission 2024).

Institutionally, the country has taken important steps to safeguard its electoral integrity. The State Election Commission (SEC) and the State Commission for the Prevention of Corruption (SCPC) serve as key oversight bodies. The last Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe’s Office for Democratic Institutions and Human Rights (OSCE/ODIHR) mission report, published on 1 August 2025, states that the Electoral Code has often been amended, usually close to elections, with the last major revision in April 2024. No further reforms have followed, despite earlier attempts at inclusiveness. In June 2025, the ruling Internal Macedonian Revolutionary Organization – Democratic Party for Macedonian National Unity (VMRO-DPMNE) proposed amendments after the Constitutional Court struck down provisions on signature thresholds for independent candidates. The drafted changes also covered issues such as Municipal Election Commissions’ budgeting and financial autonomy and was expected to pass before the elections. However, the proposed changes did not pass the vote in parliament. As a result, the SEC decided to allow independent candidates to participate in local elections with only two signatures.

The OSCE report notes that while the legal framework is generally sufficient for democratic elections, gaps and ambiguities affect process clarity. Key ODIHR recommendations remain unimplemented, particularly on preventing misuse of state resources and voter pressure, ensuring greater campaign finance transparency, and strengthening media regulation and oversight. These deficiencies erode confidence in governance and leave room for both domestic and foreign actors to exploit public disillusionment.

Ethnic power-sharing between Macedonian and Albanian political blocs adds another layer of complexity. While this arrangement has helped maintain stability, it has also institutionalized clientelism and weakened accountability. International IDEA’s Global State of Democracy Indices characterize North Macedonia as a mid-range-performing democracy, with both advancements and setbacks in recent years. Persistent issues include gender-based violence and anti-LGBTQ+ discrimination; corruption; weak access to justice; and systemic governance failures—exemplified by the March 2025 Kočani nightclub fire tragedy when 62 people died (International IDEA n.d.).

These ongoing challenges are partially offset by mitigating factors: North Macedonia’s European Union integration process, a vibrant civil society and international support for democratic reforms. The 2014–2016 wiretapping scandal (Berendt 2015) and resulting EU-brokered Przino Agreement1 demonstrate the depth of institutional vulnerabilities—but also the potential for reform when pressures align.

FIMI threats compound structural issues. Actors like Russia and others exploit ethnic tensions and domestic scepticism towards Euro–Atlantic integration, often deploying coordinated disinformation campaigns. These operations typically leverage local proxies and digital platforms to spread divisive narratives questioning the legitimacy of democratic institutions (Simonovska 2024).

Low digital literacy, under-regulated online political advertising and a fragmented regulatory environment exacerbate North Macedonia’s susceptibility. Additional risk factors include diaspora voting loopholes, weak oversight of third-party campaigners and uneven enforcement of online content rules—all fertile ground for future manipulation.

1.2. Inadequate political finance regulations

North Macedonia’s political finance system is governed by the Law on the Financing of Political Parties (Macedonia, Republic of 2006) and the Electoral Code (Macedonia, Republic of 2024). These laws define the permissible sources of campaign funding, expenditure limits and disclosure obligations. However, the framework suffers significant shortcomings in both scope and implementation, particularly in the context of digital campaigning.

The European Commission’s 2024 country report underscores that while legal provisions are in place, they are not enforced consistently, which undermines transparency and accountability in political financing. The legislation lacks clarity around online campaign spending, data-driven political ads and the use of influencers in political communications (European Commission 2024).

As political campaigns increasingly shift to digital platforms, these regulatory blind spots become more problematic. There are currently no clear rules on how parties should declare expenditure on online advertising or social media promotions. This has led to the proliferation of politically affiliated online media outlets that operate with minimal oversight. Metamorphosis Foundation has observed serious lapses in transparency and oversight of political advertisements online during election periods (Metamorphosis Foundation 2025a, 2025b).

The loopholes in the political finance framework not only impair domestic transparency but also leave the system open to foreign interference. The lack of stringent disclosure requirements for digital campaign funding makes it difficult to trace financial flows or detect foreign-sponsored influence operations. According to a survey by the International Republican Institute, the public is increasingly concerned about the misuse of political party financing and foreign influence in the country’s politics (International Republican Institute 2022).

Although the Open Government Partnership’s 2024–2026 Action Plan includes commitments to improve transparency, such as the digitalization of political finance reporting and new public consultation tools (OGP 2024), the practical implementation of these commitments remains in the early stages. The SEC and SCPC currently lack the digital infrastructure and trained personnel needed to monitor the evolving campaign finance landscape effectively. Comprehensive reform is urgently needed to align political finance oversight with the realities of digital campaigning. This includes developing clear legal standards for online spending, strengthening oversight bodies, and improving public access to financial records.

In North Macedonia, gender is increasingly weaponized in FIMI campaigns. In the last few years, disinformation targeting women, gender equality and LGBTQ+ rights has escalated in both frequency and sophistication, particularly around moments of political or social reform. Radical narratives that initially emerged at the extremes have now become embedded in broader geopolitical, religious and ideological conflict. These are amplified by both domestic actors and foreign-aligned media ecosystems.

A pivotal moment in this trend was the coordinated opposition to the draft Law on Gender Equality and the Law on Registration Records in 2023. Although still in public consultation, the laws sparked mass mobilization by religious communities associated with the Macedonian Orthodox Church, among others. Under the populist slogan ‘We have a duty to protect our children’, the campaign framed the legal recognition of gender identity as a direct threat to family values and children’s safety (360stepeni.mk 2023b). This language mirrors anti-gender movements seen across Europe, where gender rights are portrayed as part of a foreign, morally corrupt agenda.

These narratives did not emerge spontaneously or in isolation from other contested issues. A comprehensive review of over 80 cases of gender-related disinformation (Kovachevska and Janjić 2025)—documented by the Reporting Diversity Network using North Macedonia’s sole fact-checking platform, Truthmeter—reveals consistent and concerning patterns. Between 2021 and 2024, disinformation evolved from health-related fearmongering during the Covid-19 pandemic—particularly targeting pregnant women—to campaigns against women in politics (Jovanovska and Milenkovska 2024). In 2023 and 2024, the volume of gender disinformation doubled (Kovachevska and Janjić 2025), with a marked increase in narratives undermining female leaders, misgendering women, and linking gender equality to foreign influence or ‘Western decadence’.

A core tactic of gendered FIMI in North Macedonia is the deliberate coordination and integration of gender-based attacks with political and geopolitical messaging. Female politicians, particularly those aligned with Euro–Atlantic integration, are frequently targeted and portrayed as ‘Western puppets’ lacking autonomy. Former Minister of Defence Slavjanka Petrovska, for example, has been depicted as corrupt and blindly following Western agendas. In some such narratives, she has been accused of endangering national sovereignty by ‘sending Macedonian soldiers to their deaths’ for foreign interests (cf. Truthmeter 2022).

Furthermore, gendered FIMI employs visual manipulation and identity-based targeting. Images of women are frequently altered or taken out of context to provoke moral panic or ridicule. A common tactic involves falsely labelling women as transgender to stir outrage, as seen in the cases of public figures like Kamala Harris or Michelle Obama (narratives that are also common in Russian-backed propaganda outlets). The language in these campaigns is telling. Terms like ‘gender ideology’, ‘satanist’ and ‘Nazi’ are frequently used to describe women leaders, activists and LGBTQ+ supporters (see e.g. Prezemi Odgovornost 2023). These rhetorical strategies serve to demonize gender equality as unnatural, anti-national and foreign. Men who support gender rights are similarly delegitimized, depicted as mentally ill or effeminate, thereby reinforcing toxic masculinity and limiting space for male allies.

Importantly, these FIMI tactics are not just about spreading lies; they are about reshaping public values and political culture. By systematically attacking gender equality, they seek to erode democratic participation, delegitimize public institutions and polarize society. Women are disincentivized from entering public life, non-governmental organizations working on gender are vilified, and public trust in reformist or pro-European policy efforts is undermined.

In this context, gendered disinformation is not a side issue but a central pillar of broader FIMI strategies. It intersects with authoritarian ideology, foreign influence, religious conservatism and anti-democratic sentiment. Tackling FIMI in North Macedonia—and across the region—requires a nuanced understanding of how gender is embedded in information warfare. Without this lens, efforts to counter disinformation will fail to address one of its most insidious and socially damaging dimensions.

2.1. Public discourse: Division and polarization

Public discourse in North Macedonia is highly polarized across several dimensions, a situation rooted in the country’s complex historical context, including the inter-ethnic conflict (Marusic 2021) and ongoing struggles over national identity (Benazzo, Carlone and Napolitano 2019). These divisions are further reinforced by the political structure, which is often organized along ethnic lines, and by party alignments and associated campaigning tactics. The most prominent dividing factors are nationality and political affiliation, which are often co-constructive and mutually reinforcing. As a result, constructive dialogue and consensus-building are difficult. This polarization of political debate affects not only political institutions but also everyday social interactions, media narratives and public attitudes to the democratic process.

One of the most divisive issues in recent years has been the country’s name change, which has sharply split the ethnic Macedonian population. The debate framed individuals as either ‘traitors’ for supporting the Prespa Agreement (Final Agreement 2018) or ‘patriots’ for opposing it, creating a deep societal rift. Even after the issue was formally resolved, the polarization persisted through labels like ‘Severdzan’ (a derogatory term derived from ‘North Macedonia’) used to stigmatize those who accepted the new name. At the same time, the Albanian population in North Macedonia has often been portrayed in nationalist narratives as indifferent to the name issue, with the claim that ‘it’s not their country’ and that their primary interest lies in EU integration.

This tactic of framing complex political compromises as betrayals has continued with the debate around the French proposal for opening EU accession negotiations. The proposal (EU 2022), which includes a requirement to amend the Constitution to recognize Bulgarians as a minority, has reignited nationalist tensions. Much like the name change controversy, political actors and media outlets have portrayed supporters of the constitutional change as traitors who are willing to ‘sell out’ national interests, while opponents are celebrated as defenders of national dignity. In parallel, an increasingly vocal anti-EU narrative has emerged, fuelled by perceptions that the European Union is placing unfair or humiliating demands on North Macedonia.

Another persistent source of polarization is the debate around ethnic relations in public institutions, particularly the functioning of the ‘balancer’ mechanism, which was introduced to ensure fair representation of ethnic communities in state administration. Recent changes and proposals to adjust this system have reignited tensions, raising questions about the rights of the Albanian minority and whether they are being expanded at the expense of the ethnic Macedonian majority.

Gender identity and LGBTQ+ rights have long been polarizing issues in North Macedonia, but tensions escalated significantly with the drafting of the Law on Gender Equality (European Commission for Democracy through Law 2021) and the Law on Civil Registration (Group of MPs 2023). Although both laws remained in draft form (Radio Free Europe in Macedonia 2023), the ministry responsible called for broad public consultations to foster inclusive dialogue and gather input before finalizing the legislation. However, rather than encouraging constructive debate, the process became a flashpoint for intensified culture wars. Religious institutions, particularly the Orthodox Church, shifted their messaging away from discussions on gender equality and began promoting populist anti-LGBTQ+ narratives (Telma.mk 2023; Libertas.mk 2023). These communications not only targeted the content of the proposed laws but also vilified civil society organizations (CSOs) working on gender and LGBTQ+ rights, accusing them of undermining ‘traditional values’ and the social fabric.

2.2. Political discourse: Exclusion and antagonism

In North Macedonia, political polarization is not only deeply entrenched along ethnic lines but also increasingly shaped by ideological divides, particularly between liberal and conservative forces. Within the ethnic Macedonian political spectrum, the Social Democratic Union of Macedonia (see SDSM n.d.) is widely viewed as a liberal, pro-European party that supports reform, inclusion and EU integration. Currently in opposition, the SDSM promotes policies that align with EU democratic standards, including minority rights and gender equality. In contrast, the ruling VMRO-DPMNE party presents itself as a conservative force defending national interests and traditional values (VMRO-DPMNE n.d.; Kanal 5 2022). It often positions itself as a guardian of Macedonian dignity, expressing scepticism towards perceived external pressures from Brussels and advocating for the preservation of national identity and sovereignty.

This ideological rift intensifies when set against the backdrop of EU integration. Supporters of EU accession are portrayed by their opponents as overly willing to compromise on national issues, such as accepting broader rights for Albanians, LGBTQ+ protections and constitutional amendments to satisfy Brussels (Vecer.mk 2025). Conservative forces frame themselves, on the other hand, as defenders of national honour who resist what they characterize as EU blackmail and foreign imposition.

Within the ethnic Albanian political landscape, the divide takes a different form but feeds into the same broader polarization. For example, the VLEN coalition, a relatively new reform-oriented political alliance representing the Albanian minority, emphasizes democratization, anti-corruption and cross-ethnic cooperation (VLEN n.d.). VLEN is seen as more open to working with Macedonian parties and engaging in institutional reform, aligning themselves with pro-European values. In contrast, the Democratic Union for Integration (DUI), the long-dominant Albanian party in opposition, often frames its political role as the primary defender of Albanian interests against Macedonian nationalism (see press24.mk 2025). Critics accuse the DUI of perpetuating ethnic clientelism and prioritizing ethnic representation over systemic reform.

These exclusionary and polarized narratives may be domestically generated but are also actively exploited by pro-Russian actors and disinformation proxies. In fact, many of the populist messages—framing EU integration as betrayal, portraying minority rights as a threat to national identity, and attacking gender and LGBTQ+ rights—are perfectly aligned with Kremlin talking points and require no significant adaptation.

2.3. Domestic proxies

Domestic proxies of foreign influence operate fluidly across sectors, from politics and civil society to business. While some of these actors have clear links to foreign donors or ideological allies, others function more ambiguously, acting as amplifiers of anti-Western or anti-democratic narratives without any direct, proven connection to foreign governments.

There are several prominent CSOs that act as domestic proxy groups contributing to polarized discourse in North Macedonia; all promote anti-gender rhetoric under the guise of defending children’s rights (Gagovski 2024) and traditionalist values. While presenting itself as apolitical and concerned with the well-being of minors, the Coalition for Protection of Children has been a vocal opponent of comprehensive sex education and has strongly resisted legislative efforts to advance gender equality and LGBTQ+ rights. It has been especially influential in shaping public opinion and pressuring government institutions to water down or delay progressive policies—most notably the draft Law on Gender Equality. The Coalition is ideologically aligned with the Rodina party (see Rodina Makedonija n.d.), a political entity that has been publicly identified as a pro-Russian party and is known for spreading Kremlin-aligned narratives (Petrovski, Ismaili and Kovachevska 2024).

Levica (see Levica n.d.) is a far-left, Eurosceptic party known for its alignment with Russia and China and promotion of a multipolar world. It regularly criticizes EU and NATO policies, frames Western influence as imperialist, and opposes key reforms tied to minority rights and EU integration. The party has also engaged in meetings with Russian officials, reinforcing its anti-Western credentials.

Patriotic Society is a nationalist group in North Macedonia that claims to promote patriotism but regularly spreads ethnic hatred (Meta.mk 2024), especially towards Albanians, and uses anti-LGBTQ+ and misogynistic rhetoric. Through social media and podcasts, Patriotic Society glorifies a narrow definition of Macedonian identity while labelling others as traitors, often advocating violence and exclusion.

2.4. Audience susceptibility

Many reports on public opinion in North Macedonia show a high susceptibility to Eurosceptic disinformation, especially among audiences with low media literacy. Combined with media and political messaging that exploits existing biases, this makes North Macedonia particularly vulnerable to polarization and foreign influence.

Recent surveys show a growing Euroscepticism among major political parties in North Macedonia. Notably, 61 per cent of VMRO-DPMNE voters and 62 per cent of Levica supporters believe that EU membership is not beneficial for the country (360stepeni.mk 2023a), reflecting a broader trend of disillusionment with the EU found also on the country’s conservative right and radical left.

According to recent data, 82 per cent of ethnic Macedonians as compared with 11.3 per cent of ethnic Albanians oppose the constitutional amendments required to start EU accession talks—specifically, the inclusion of Bulgarians in the Constitution (Lider.mk 2025). This disparity is often used to reinforce the divisive narrative that Albanians are indifferent to Macedonian national interests and identity.

A general distrust of state institutions and of the media has created fertile ground for disinformation to thrive. Citizens increasingly believe that all political actors, regardless of party or ideology, spread disinformation to some degree. In research by Metamorphosis Foundation (Mitrevski 2024), when asked which actors are responsible, around 48 per cent of respondents named the diplomatic services of Russia, the EU and the United States. This suggests that narratives portraying Western actors as no better than Russia have succeeded in blurring the lines between democratic and authoritarian influences. At the same time, citizens show a high level of susceptibility to conspiracy theories: 62 per cent believe that ‘globalists or elitists control events in the world’, 66 per cent think Covid-19 was intentionally created and 28 per cent believe there is no need for vaccines ‘since vaccine-preventable diseases can be overcome by immunity alone’. These beliefs are in large part a direct result of low media literacy, widespread disinformation and a generalized lack of trust in institutions, leaving the public vulnerable to manipulation and polarizing narratives.

North Macedonia’s media ecosystem is outwardly pluralistic but lacking in balance and independence. Although there is a mix of public service broadcasters, private media and online portals, this generally fails to translate into true choice and competition of viewpoints due to concentrated ownership, political influence and outlets’ financial vulnerability.

The Media Ownership Monitor (BIRN 2023) reports that a small group of companies control a significant share of both the market and audience reach, often through opaque ownership structures and cross-media holdings. The lack of transparency around ownership further erodes media independence, allowing political and corporate elites to shape editorial policies behind the scenes. Specifically, private media frequently depend on public advertising funds, which are disproportionately allocated to outlets with favourable coverage of ruling parties. This financial leverage compromises editorial independence and fosters self-censorship. The International Press Institute warns that this practice creates a climate where investigative journalism is discouraged and politically sensitive stories are often avoided (Association of Journalists of Macedonia 2023).

Macedonian Radio Television (MRT), the country’s public broadcaster, is formally tasked with providing impartial content under the Law on Audio and Audiovisual Media Services 2017 (amended in 2024). In practice, however, the MRT’s reliance on state financing leaves it vulnerable to political interference, particularly in pre-election periods. Analysis by the Goethe-Institut (Tahiri 2021) confirms that the MRT struggles with both financial autonomy and political pressure, limiting its role as an impartial public service broadcaster.

Although Internet penetration in North Macedonia is relatively high (Kemp 2024), reaching over 92 per cent of the population, this has not ensured equal access to reliable information. In accessing and selecting content, rural communities and ethnic minorities often face language gaps, a scarcity of local media outlets and lower levels of digital literacy. These structural inequalities contribute to an uneven information landscape that leaves certain groups more vulnerable to FIMI and media biases more broadly.

State funding plays an increasingly prominent role in North Macedonia’s media sector, raising concerns about media independence and potential clientelism. Funding mechanisms are often opaque and limited, leaving independent outlets dependent on donors. While direct subsidies (mostly for print) are modest and declining, indirect state financing through paid political advertising and state-sponsored ‘public interest’ campaigns now form a substantial revenue stream. In 2024 alone, political advertising during elections exceeded EUR 10 million, with online portals receiving over EUR 800,000 for the parliamentary polls (Jordanovska 2024). The combined total for political advertising on online portals for both the presidential and parliamentary elections that year is estimated at EUR 2 million. This system disproportionately benefits large parties and politically aligned media and lacks proper oversight (see Metamorphosis Foundation 2025a).

The pattern of a few dominant media narratives, combined with weak regulatory enforcement and limited journalistic resources, has led to the prevalence of what is referred to as ‘copy-paste journalism’. In this model, content is frequently republished from other outlets without proper verification or context, further weakening public confidence in media reliability compared to the years following independence.

As media polarization intensifies, and financial and political pressures mount, the space for independent, investigative and high-quality journalism—a cornerstone of democratic resilience—continues to shrink. This creates an environment for disinformation to flourish, further compounded by poor regulation, lack of transparency and weak accountability mechanisms. Online disinformation and ethical violations are rampant. The media’s self-regulatory bodies like the Council of Media Ethics are accordingly overwhelmed and struggle to address the volume of complaints, especially online. Although media literacy efforts have grown, particularly through a curriculum introduced in 2021 and civil society initiatives, these were mostly donor-funded and may not continue without renewed support. Examples of these initiatives include the Metamorphosis Foundation’s initiative for a whole-of-society approach in countering disinformation and the United States Agency for International Development funded YouThink project.

3.1. Influence of foreign-aligned media

While North Macedonia’s media system is not characterized by extensive foreign ownership, the influence of foreign-aligned narratives—particularly from Russia and China—is pervasive and growing (Balkan Insight 2024, n.d.). These influences are exerted through content-sharing, syndication, republishing foreign state media content and the use of domestic proxies.

Chinese state media such as Xinhua News Agency and China Global Television Network (CGTN) maintain correspondents in Skopje and collaborate with local outlets to publish content emphasizing China’s global leadership and economic generosity. These narratives often portray China as a development partner while minimizing discourse on issues such as debt dependency, lack of transparency in Chinese infrastructure projects, or potential governance concerns tied to Chinese investment (Blazevski 2023).

Russian influence is more overt and politically charged. Content from Sputnik, RT and other Kremlin-backed sources is frequently republished by Macedonian websites with little to no editorial filtering. These narratives promote scepticism towards the EU and NATO, question the legitimacy of democratic institutions, and often emphasize historical grievances and cultural alignment with Russia (Simonovska 2024). Strategic messaging focuses on portraying the West as decadent or hegemonic, and on delegitimizing reforms linked to Euro–Atlantic integration.

The spread of such narratives is facilitated by Macedonian media outlets that willingly enter syndication or content re-use arrangements, as well as by ideologically sympathetic actors within the country. In some cases, these relationships are supported by financial or material incentives. A notable tactic for enhancing credibility and reach is the use of local language, branding and media personalities to give foreign-origin content a domestic appearance. The EU Institute for Security Studies notes that the use of local voices and domestic-facing platforms is a hallmark of contemporary influence operations. Foreign actors invest in local legitimacy, using familiar formats and culturally resonant messages to mask the external origin of the narratives (Zorić 2025). This tactic significantly complicates the ability of media consumers to discern credible information from manipulative content.

Election periods are particularly vulnerable to foreign information manipulation. Investigative reports and academic studies have documented coordinated attempts to influence voter behaviour and public sentiment during election campaigns, often through social media and websites that appear to be locally run but push content aligned with foreign strategic interests (Palloshi Disha et al. 2025).

These influence campaigns are not limited to news portals. They extend to cultural, educational and economic spheres, including Confucius Institutes, cultural events and scholarships that serve to normalize state-sponsored foreign narratives. The long-term strategic goal is to create favourable perceptions of the sponsoring states while undermining North Macedonia’s democratic norms and institutions.

3.2. Journalistic standards

North Macedonia’s information ecosystem suffers not only from foreign influence and structural vulnerabilities but also from endemic weaknesses in journalistic quality. These include economic pressures on media workers, political interference and limited institutional safeguards for professional standards. According to the Vibrant Information Barometer (VIBE) (IREX 2022), North Macedonia’s media environment is classified as ‘Not Vibrant’, reflecting the sector’s lack of editorial independence, reporting accuracy and public accountability. Under such conditions, disinformation and propaganda flourish, leaving citizens without access to credible, comprehensive or diverse sources of information.

One of the root causes of declining journalistic quality is economic precarity. Journalists in North Macedonia frequently earn less than the national average wage, with entry-level salaries hovering around EUR 250 to EUR 450 per month. Many work under casualized contracts, lack social protections and therefore face livelihood insecurity, especially those working in smaller or independent outlets. This makes them highly vulnerable to pressures including bribery, editorial coercion or self-censorship.

Efforts to improve journalistic capacity do exist. Organizations such as the Metamorphosis Foundation have launched fact-checking portals and digital literacy programmes to counter disinformation. In parallel, international organizations like the International Center for Journalists have supported local journalists with training in data journalism, verification techniques and pre-bunking strategies (Dibbert and Orr 2024).

Despite these interventions, the working conditions of journalists remain precarious. Many operate in a climate of fear. Harassment, threats and intimidation are routine, especially for those covering politically sensitive or socially divisive topics. Female journalists face additional risks: targeted online abuse, sexist defamation and doxxing. Several cases have involved physical threats or surveillance; the response from public authorities is often insufficient or dismissive.

This deteriorating professional environment weakens the media’s role as a democratic pillar and watchdog. Without comprehensive labour protections, robust ethical enforcement and sustained support for investigative reporting, North Macedonia’s journalistic standards will remain vulnerable to both internal decay and external exploitation.

3.3. Declining trust in mainstream news

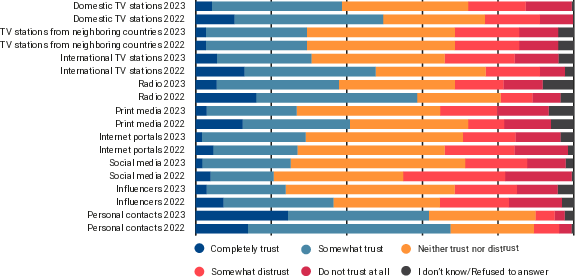

Trust in the media is steadily declining. The abovementioned survey by Metamorphosis Foundation (see Figure 3.1) shows that more than 64 per cent of the population is informed on a day-to-day basis by talking to their personal contacts. This is the only information source showing a rise in ‘complete trust’ during the period (with a slight decline in complete or ‘somewhat’ trusting attitudes combined). Public trust in traditional media (TV stations, radio and print media) is higher than that placed in digital media. Specifically, 39 per cent of citizens completely or somewhat trust domestic TV stations, 30 per cent trust TV stations from neighbouring countries, 21 per cent trust international TV stations, 38 per cent trust radio stations, and 27 per cent trust print media.

While national TV channels and print newspapers remain active, their influence is waning, particularly among younger audiences who increasingly turn to social media platforms such as Facebook, YouTube and TikTok for news consumption. This shift is most pronounced during election cycles and periods of political unrest, when social platforms become primary sources of information. Lacking in editorial oversight, these digital environments enable the unchecked spread of conspiracy theories, clickbait and politically motivated disinformation.

Faced with their declining reach, many traditional media outlets have adopted a ‘breaking news’ model to compete with the speed of digital content. In doing so, they frequently sacrifice depth and context, favouring sensationalism over accuracy and engaging in ‘copy-paste’ reporting as described above.

A growing segment of the population is turning to non-traditional sources for information: blogs, independent portals, influencers and opinion-based YouTube channels. These platforms often provide alternative perspectives but are rarely subject to professional journalistic standards. Without editorial accountability or fact-checking, these sources can amplify divisive or false narratives.

The erosion of trust in media has been deliberately exploited by politically affiliated actors who push anti-media rhetoric and discredit established journalism as corrupt, biased or elitist. Such narratives are often amplified by foreign-aligned networks that frame Western media institutions as complicit in foreign policy agendas and/or otherwise manipulative. The VIBE 2024 assessment highlights how this dynamic has significantly increased public scepticism and disengagement from traditional media institutions (IREX 2024).

The regulatory framework for online political communication remains underdeveloped. North Macedonia lacks clear rules for digital political advertising, campaign transparency or platform accountability. As a result, political content can circulate widely without disclosure of funding, sponsorship or origin—making it difficult for citizens to assess the authenticity and motivation of the messages they encounter.

CSOs have called for urgent reforms that will improve transparency, advocating for greater media literacy efforts and stronger partnerships between regulators, tech platforms and watchdog organizations. A key concern is ensuring that the media fulfils its democratic role as a source of accurate information and public accountability. However, these measures have yet to be implemented at scale, leaving a critical gap in North Macedonia’s democratic resilience.

Rebuilding trust in media will require a multifaceted approach: enhancing media literacy in schools, enforcing ethical standards across all media platforms, investing in investigative journalism and ensuring political neutrality in the distribution of public funds. Until then, the public’s reliance on fragmented, often unreliable sources of information will continue to undermine the foundations of an informed, democratic society.

4.1. Fragmented information environments

The country’s digital information environment is shaped by both longstanding societal divisions and the disruptive influence of digital media. Multiple studies and monitoring reports confirm that the country’s online sphere is deeply segmented along ethnic, political and ideological lines, with these divisions mirrored and amplified in digital and social media spaces (Micevski and Trpevska 2023; Palloshi Disha, Halili and Rustemi 2023). This fragmentation is not only an inevitable product of the country’s multi-ethnic composition but also results from the proliferation of digital media outlets and online platforms’ expansion, which have outpaced policy responses and self-regulatory efforts.

Empirical research (Feta, Armakolas and Krstinovska 2023; Ilazi et al. 2022) has documented the formation of echo chambers on Facebook, Telegram and other platforms, whereby users cluster around shared political or ethnic identities and are exposed primarily to content that reinforces their pre-existing beliefs. During election cycles, these echo chambers become especially salient as political actors and malign influencers exploit confirmation bias to mobilize via divisive or extremist narratives (Gudachi 2024). The 2024 elections, for example, saw a surge in negative online discourses (Trojachanec and Rizaov 2024). That is, smear campaigns and targeted misinformation—with digital platforms serving as primary vectors—undermined trust in institutions and deepened inter-ethnic divisions. Research by the Institute for Communication Studies underscores how historic grievances, ethnic identity and conspiracy theories have been deployed to foster exclusionary politics and delegitimize opponents (Trajkoska et al. 2024).

Recent analyses (Ross Arguedas et al. 2022) highlight that social media algorithms, designed to maximize user engagement, systematically curate content that aligns with users’ existing preferences, thereby narrowing exposure to diverse viewpoints and reinforcing confirmation bias. This process not only homogenizes online discourse within groups but also accelerates the spread of misinformation, making users more susceptible to manipulation and less likely to encounter corrective information or alternative perspectives. The result is an entrenched digital polarization that stifles critical debate and impedes democratic deliberation.

4.2. Exploitability of digital and social media technologies

The most used, and most targeted, digital technologies involve multiple vulnerability factors. Facebook, Telegram, YouTube and alternative platforms such as Parler produce algorithmic amplification, have low barriers to account creation and are moderated only weakly. During the 2024 election cycle, political actors and malign influencers leveraged these factors with tactics including coordinated use of fake and anonymous accounts, amplification of unverified claims and strategic deployment of emotionally charged content to maximize engagement and virality.

Evidence from the Balkan Investigative Reporting Network (BIRN) and the Institute for Strategic Dialogue Germany reports demonstrates that targeted disinformation campaigns systematically exploited the affordances of social media for microtargeting and echo chamber formation (Nikolic 2020). Facebook and Telegram groups were used to mobilize supporters and spread anti-Western, pro-Kremlin and anti-minority narratives, with more than 60 per cent of monitored messages expressing anti-Western sentiment and 24 per cent pro-Kremlin positions. Political parties and actors routinely framed opponents as existential threats to national or ethnic identity, using historic grievances and exclusionary rhetoric to drive polarization. The use of rhetorical questions, fake accounts and monolingual content streams further entrenched filter bubbles and limited cross-community engagement.

While there has been growing concern about the potential for AI-generated content and deepfakes, the latest research finds that, as of 2024, the impact in North Macedonia remained limited. Most AI-manipulated content in circulation has focused on foreign public figures and has not yet been weaponized at scale in the domestic context, largely due to linguistic and technical barriers. The only uses of deepfake technology have been found in scammer ads, impersonating well-know TV anchors and public doctors.

4.3. Gaps in moderation policies

Efforts to mitigate these digital platform vulnerabilities have largely been led by civil society. Initiatives such as Metamorphosis Foundation’s fact-checking service, public awareness campaigns and youth engagement events (‘Cyber Shakes’) have sought to build resilience and promote media literacy. National strategies and codes of conduct have been discussed, but implementation remains partial and fragmented, with no comprehensive regulatory framework or coordinated institutional response thus far. As a result, while some progress has been made in public engagement and awareness, the overall effectiveness of these countermeasures remains limited.

Worse, the relaxation of Meta/Facebook content moderation policies will have an outsized impact (Trojachanec 2025)—and not only on Facebook’s already inconsistent moderation practices (as the most used social media platform). The BIRN report (Gudachi 2024) highlights how negative online discourses, personal attacks and intimidation tactics were rampant during the 2024 elections, with politicians framing opponents as existential threats to national or ethnic identity, thereby consolidating their base and delegitimizing rivals. Parties also manipulate platform features by microtargeting audiences, maintaining monolingual communication silos, and using rhetorical questions to subtly implant suspicion without direct evidence.

Amendments to the Law on Media (2013) aim to bring online outlets under regulatory oversight, with a new register for online media and enhanced transparency requirements. CSOs working on fact-checking have partnered with other organizations in the EU and beyond to report hate speech and disinformation, and so maintained better communication with platforms, especially Facebook. While these measures have shown some positive impact, the overall effectiveness remains partial, hindered by fragmented implementation, limited reach and the continuing adaptability of malign actors.

5.1. Ineffective regulatory authorities

The current government of North Macedonia, led by the conservative VMRO-DPMNE party under Prime Minister Hristijan Mickoski, has not publicly addressed the issue of FIMI. While the Metamorphosis Foundation and other CSOs have raised the alarm about the government’s handling of FIMI-related challenges (Trojachanec and Rizaov 2024), state institutions have remained largely inactive in this field.

In 2019, the previous government proposed a concrete plan to address disinformation, but since then, there has been little progress. The National Assembly has not tackled the FIMI issue in any of its committees (Trojachanec and Rizaov 2024), despite at least five committees having the mandate to do so. Only the Committee on Defence and Security has shown interest in engaging with the issue.

Moreover, concerns have been raised about the government’s approach to access to public information (Emehet 2024). Restrictions on freedom of information requests and limitations on data access from the Central Registry have sparked fears of a decline in transparency and accountability. Journalists have reported delays and denials in obtaining public information, which may hinder efforts to effectively combat FIMI.

In summary, neither the current government nor the Sobranie (Parliament of North Macedonia) have demonstrated significant initiative in addressing FIMI. Civil society organizations have repeatedly criticized this lack of political will and concrete action, highlighting how insufficient legislative proposals and weak oversight mechanisms hinder effective responses.

North Macedonia’s battle against disinformation and FIMI cannot be won by any single actor alone. As a country that used to be considered a pillar of stability in the Western Balkans, the level of its resilience or vulnerabilities has implications beyond its borders. The complexity of the challenge demands a whole-of-society approach and substantial regional engagement—a sustained, coordinated effort involving government institutions, media, civil society, private sector actors (including tech platforms and advertisers), academia and citizens. Only through shared responsibility and collective action can a resilient and trustworthy information ecosystem be built.

The stakes are high: disinformation and FIMI undermine democratic processes, erode public trust, amplify social divisions and weaken North Macedonia’s Euro–Atlantic integration aspirations. Without decisive action, the information manipulation industry will continue to adapt rapidly, outpacing regulation and exploiting systemic weaknesses. The resulting environment of mistrust and polarization threatens to destabilize society and compromise the integrity of key institutions.

Crucially, this is not merely a national issue. Given the transnational nature of digital media, disinformation flows across borders and exploits international networks. Aligning North Macedonia’s legal and policy framework with international standards such as the EU Digital Services Act (DSA) 2022 and European Media Freedom Act 2024 is essential to ensure coherent, interoperable and effective responses. Such alignment will strengthen domestic safeguards while contributing to broader regional resilience and cooperation.

Addressing disinformation and FIMI also offers an opportunity to strengthen democratic governance in North Macedonia more broadly. By promoting transparency, accountability and media literacy, the country can rebuild citizens’ trust in public institutions and empower communities to engage critically with information. Investing in independent journalism, fact-checking and civil society capacity is foundational to this endeavour.

Ultimately, building resilience against disinformation requires viewing the information ecosystem as a shared public good. It demands long-term commitment to legal reform, institutional capacity building and fostering a culture of digital responsibility and critical engagement across society.

Recommendations

1. Develop and implement a national strategy on disinformation

Establish an inclusive national coordination mechanism bringing together government bodies, media associations, civil society organizations, academic experts, tech companies and citizen representatives. This forum should foster ongoing dialogue, joint planning and shared accountability to ensure adaptive responses to evolving disinformation tactics. The strategy must align with international legal frameworks such as the DSA, Council of Europe standards, and other human rights and digital governance norms guaranteeing compliance and interoperability, and reinforcing democratic values both domestically and across borders.

2. Reform political advertising and media funding

Enforce stringent transparency requirements for political advertising, including mandatory disclosure of funding sources, ownership and editorial teams. Regulate and monitor political ad spending to prevent the proliferation of ‘phantom media’—politically affiliated outlets created purposely to acquire election funding and avoid legal spending limits. Engage private sector stakeholders, digital marketing agencies and platforms to commit to ethical advertising practices. Adopt regulatory practices aligned with the DSA’s provisions on online political ads, including transparency reports and mechanisms to prevent manipulative microtargeting, while safeguarding privacy and freedom of expression under domestic and international law.

3. Disrupt the disinformation economy through cross-sector collaboration

Support fair wages and improved working conditions for media professionals to reduce the economic incentives that drive talent towards disinformation-for-profit networks. Encourage collaboration among investigative journalists, fact-checkers and civil society watchdogs to expose disinformation campaigns and raise awareness of them. Work with digital platforms to increase algorithmic transparency and reduce the amplification of harmful, engagement-driven content. Platforms operating in North Macedonia should be held accountable to comply with DSA requirements on content moderation, risk assessment and user redress mechanisms to mitigate systemic disinformation risks.

4. Rebuild public trust through institutional transparency and media literacy

Promote greater openness and responsiveness of public institutions to rebuild citizen trust in democratic processes. Implement nationwide media literacy programmes across schools, universities and communities to equip citizens with the critical thinking skills necessary for recognizing and resisting disinformation. Empower CSOs to lead grassroots initiatives fostering dialogue, resilience and digital literacy. These efforts should embed international human rights principles, including protections for freedom of expression and privacy, ensuring balanced and inclusive public awareness.

5. Strengthen legal and regulatory frameworks with cross-sector engagement

Update and harmonize laws regulating digital content, political advertising, microtargeting and online hate speech to make them effective, enforceable and consistent with democratic norms. Empower regulatory bodies with adequate resources, independence and authority to monitor and respond to disinformation threats across all media formats. Facilitate ongoing cooperation among government, civil society, academia and platform providers to monitor compliance and swiftly address emerging challenges. Ensure that domestic legislation is fully aligned with the EU DSA and other relevant international legal standards, fostering cross-border cooperation and enabling robust enforcement mechanisms.

- The 2015 Przino Agreement, brokered by the EU, was reached after a political crisis triggered by a wiretapping scandal; it required the inclusion of the opposition in government, the resignation of Prime Minister Gruevski, the appointment of a special prosecutor, and the holding of early elections to restore stability and accountability (see Marusic 2019).

Abbreviations

| BIRN | Balkan Investigative Reporting Network |

|---|---|

| CSO | Civil society organization |

| DSA | Digital Services Act 2022 of the European Union |

| DUI | Democratic Union for Integration |

| FIMI | Foreign information manipulation and interference |

| LGBTQ+ | Lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender and queer |

| MRT | Macedonian Radio Television |

| ODIHR | Office for Democratic Institutions and Human Rights |

| OSCE | Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe |

| SCPC | State Commission for the Prevention of Corruption |

| SDSM | Social Democratic Union of Macedonia |

| SEC | State Election Commission |

| VIBE | Vibrant Information Barometer |

We would like to express our sincere gratitude to the team at Metamorphosis Foundation for their valuable contributions towards the drafting of this report. Special thanks to authors Matej Trojachanec, journalist and researcher; Despina Kovachevska, media monitoring specialist; and Goran Rizaov, journalist and manager, Information and Media Integrity programme.

We are also grateful to the project team at International IDEA: Khushbu Agrawal, Sebastian Becker, Alberto Fernandez Gibaja, Yukihiko Hamada and Blerta Hoxha for their leadership and guidance throughout the research process. Sincere appreciation to Katarzyna Gardapkhadze for her thoughtful review and critical reflections on the draft; to Lisa Hagman who oversaw the production of the report; and to Andrew Robertson, Jenefrieda Isberg and Jonida Shehu for their support in editorial and administrative tasks.

Special thanks are due to the participants of the validation meeting held in Skopje in June 2025 whose engagement, local perspectives and constructive input helped ground the findings in the realities of the North Macedonian information environment.

This report has been made possible through the support of Global Affairs Canada.

360stepeni.mk, ‘За 61% од гласачите на ВМРО-ДПМНЕ и за 62% од поддржувачите на Левица членство во ЕУ не е добра работа’ [For 61% of VMRO-DPMNE voters and 62% of Levica supporters, EU membership is not a good thing], February 2023a, <https://360stepeni.mk/za-61-od-glasachite-na-vmro-dpmne-i-za-62-od-poddrzhuvachite-na-levitsa-chlenstvo-vo-eu-ne-e-dobra-rabota>, accessed 4 August 2025

—, ‘МПЦ ОА повикува на протест на 29 јуни во Скопје против предлог-законите за матична евиденција и родова еднаквост’ [MOC OA calls for protest on June 29 in Skopje against draft laws on civil registration and gender equality], July 2023b, <https://360stepeni.mk/mpts-oa-povikuva-na-protest-na-29-juni-vo-skopje-protiv-predlog-zakonite-za-matichna-evidentsija-i-rodova-ednakvost>, accessed 4 August 2025

Association of Journalists of Macedonia, ‘Media Freedom in North Macedonia: Fragile Progress: Fact-Finding Press Freedom Mission Report’, Skopje, 5–7 June 2023, <https://ipi.media/wp-content/uploads/2023/10/EN-Fact-Finding-PFM-Report-251023-web-1.pdf>, accessed 5 August 2025

Balkan Insight, ‘China in the Balkans’, [n.d.], <https://balkaninsight.com/mk/china-in-the-balkans>, accessed 4 August 2025

—, ‘BIRN doc lifts lid on Russian disinformation in Balkans’, 10 May 2024, <https://balkaninsight.com/2024/05/10/birn-doc-lifts-lid-on-russian-disinformation-in-balkans>, accessed 4 August 2025

Balkan Investigative Reporting Network (BIRN), Media Ownership Monitor, ‘North Macedonia 2023’, 12 November 2023, <https://north-macedonia.mom-gmr.org/en>, accessed 5 August 2025

Benazzo, S., Carlone, M. and Napolitano, M., ‘North Macedonia might have a name but does it have a national identity?’, Euronews, 27 January 2019 <https://www.euronews.com/2019/01/27/north-macedonia-might-be-born-but-does-it-have-a-national-identity>, accessed 5 August 2025

Berendt, J., ‘Macedonia government is blamed for wiretapping scandal’, New York Times, 22 June 2015, <https://www.nytimes.com/2015/06/22/world/europe/macedonia-government-is-blamed-for-wiretapping-scandal.html>, accessed 4 August 2025

Blazevski, B., ‘Behind the scenes: Chinese influence in North Macedonia’, Meta.mk, 8 March 2023, <https://meta.mk/en/behind-the-scenes-chinese-influence-in-north-macedonia>, accessed 5 August 2025

Dibbert, T. and Orr, B., ‘Metamorphosis Foundation is navigating North Macedonia’s complicated disinformation landscape’, International Journalists’ Network, 2 April 2024, <https://ijnet.org/en/story/metamorphosis-foundation-navigating-north-macedonia%E2%80%99s-complicated-disinformation-landscape>, accessed 5 August 2025

Emehet, E., ‘North Macedonia’s new government faces criticism over access to information’, EU Balkan News, 25 October 2024, <https://balkaneu.com/north-macedonias-new-government-faces-criticism-over-access-to-information>, accessed 5 August 2025

European Commission, ‘North Macedonia 2024 Report’, SWD(2024) 693 final, 30 October 2024, <

European Commission for Democracy Through Law (Venice Commission), North Macedonia Draft Law on Gender Equality, Opinion No. 1037/2021, 28 May 2021, <https://www.venice.coe.int/webforms/documents/?pdf=CDL-REF(2021)044-e>, accessed 28 August 2025

European Parliament and the Council of the European Union, European Media Freedom Act, 20 March 2024, <https://data.consilium.europa.eu/doc/document/PE-4-2024-INIT/en/pdf>, accessed 28 August 2025

European Union, ‘Ministerial Meeting of the Intergovernmental Conference Completing the Opening of the Negotiations on the Accession of North Macedonia to the European Union, General EU Position’, June 2022, <https://vlada.mk/sites/default/files/dokumenti/draft_general_eu_position.pdf>, accessed 5 August 2025

Feta, B., Armakolas, I. and Krstinovska, A., ‘Understanding the Relationship between Tradicalisation and the Media in North Macedonia’, Policy Paper 141/2023, Hellenic Foundation for European & Foreign Policy (ELIAMEP), July 2023, <https://www.eliamep.gr/wp-content/uploads/2023/07/Policy-Paper-141-PAVE-ELIAMEP-second-paper_FINAL.pdf>, accessed 5 August 2025

‘Final Agreement for the Settlement of the Differences as Described in the United Nation’s Security Council Resolutions 817 (1993) and 845 (1993), the Termination of the Interim Accord 1995, and the Establishment of a Strategic Partnership Between the Parties’, signed 17 June 2018, <https://www.mfa.gr/images/docs/eidikathemata/agreement.pdf>, accessed 5 August 2025

Gagovski, B., ‘When medical students apologize – the impact of the anti-gender movement in the public sphere’, Meta.mk, 23 April 2024, <https://meta.mk/en/when-medical-students-apologize-the-impact-of-the-anti-gender-movement-in-the-public-sphere>, accessed 5 August 2025

Giulio Sicurella, F. and Morača, T., Analysing Enablers and Incentives of Election-Related Foreign Information Manipulation and Interference: A Global Methodology (Stockholm: International IDEA, 2025), <https://doi.org/10.31752/idea.2025.48>

Group of MPs, ПРЕДЛОГ НА ЗАКОН ЗА ДОПОЛНУВАЊЕ НА ЗАКОНОТ ЗА МАТИЧНАТА ЕВИДЕНЦИЈА [Proposal of a Law to Supplement the Law on Civil Registry 2023], Parliament of the Republic of North Macedonia, June 2023, <https://www.sobranie.mk/detali-na-materijal.nspx?param=7ec7622f-eec3-4be5-8f22-4c41cb49a63c>, accessed 28 August 2025

Gudachi, V., Online Narratives and Discrimination: Stakes for Minorities in North Macedonian Elections (Belgrade: BIRN, 2024), <https://balkaninsight.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/06/Online-narratives-and-discrimination.pdf>, accessed 4 August 2025

Ilazi, R., Orana, A., Avdimetaj, T., Feta, B., Krstinovska, A., Christidis, Y. and Armakolas, I., Online and Offline (De)radicalisation in the Balkans, Working Paper 5 (PAVE Project Publications, 2022), <https://www.eliamep.gr/wp-content/uploads/2022/05/PAVE-D5.1-Online-and-Offline-Deradicalisation-in-the-Balkans.pdf>, accessed 4 August 2025

International Foundation for Electoral Systems, ‘Election FAQs: North Macedonia. Parliamentary Election May 8, 2024’, 30 April 2024, <https://www.ifes.org/sites/default/files/2024-05/North%20Macedonia%20FAQ%20May%20Parliamentary%20Elections_2024_FINAL%20VERSION.pdf>, accessed 27 August 2025

International IDEA, Global State of Democracy Index, Democracy Tracker – ‘North Macedonia’, [n.d.], <https://www.idea.int/democracytracker/country/north-macedonia>, accessed 5 August 2025

International Republican Institute (IRI), ‘Public Opinion Poll: Residents of North Macedonia’, 7 March 2022, <https://www.iri.org/resources/public-opinion-poll-residents-of-north-macedonia>, accessed 5 August 2025

IREX, Vibrant Information Barometer 2022 – ‘North Macedonia’, 2022, <https://www.irex.org/files/VIBE_2022_North_Macedonia.pdf>, accessed 5 August 2025

—, Vibrant Information Barometer 2024 – ‘North Macedonia’, 2024, <https://www.irex.org/sites/default/files/VIBE_2024_NorthMacedonia.pdf>, accessed 17 September 2025

Jordanovska, M., ‘За порталите 811 илјади евра од колачот за парламентарните избори’ [For the portals 811,000 euros from the parliamentary election cake], 4 October 2024, <https://meta.mk/za-portalite-811-iljadi-evra-od-kolachot-za-parlamentarnite-izbori>, accessed 5 August 2025

Jovanovska, B. and Milenkovska, S., Women Politicians and Media Bias (Skopje: Institute of Communication Studies (IKS), 2024), <https://iks.edu.mk/en/research-analysis/women-politicians-and-media-bias>, accessed 5 August 2025

Kanal 5 National TV, ‘ВМРО-ДПМНЕ: Претседателот Мицкоски ги брани позициите на Македонија, VMRO-DPMNE’ [President Mickoski defends Macedonia’s positions], 5 June 2022, <https://kanal5.com.mk/vmro-dpmne-pretsedatelot-mickoski-gi-brani-poziciite-na-makedonija/a533093>, accessed 5 August 2025

Kemp, S., ‘Digital 2024: North Macedonia’, Datareportal, 23 February 2024, <https://datareportal.com/reports/digital-2024-north-macedonia>, accessed 4 August 2025

Kovachevska, D. and Janjić, S., Mapping Gendered Disinformation in the Western Balkans – North Macedonia (Belgrade: Reporting Diversity Network/Media Diversity Institute Western Balkans, 2025), <https://smartbalkansproject.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/05/Mapping-gendered-disinformation-in-the-Western-Balkans-1.pdf>, accessed 5 August 2025

Levica, ‘Политичка платформа’ [Political Platform], [n.d.], <https://levica.mk/za-nas/platforma>, accessed 5 August 2025

Libertas.mk, ‘МПЦ ОА повикува на протест на 29 јуни во Скопје против предлог-законите за матична евиденција и родова еднаквост’ [MOC OA calls for protest on June 29 in Skopje against draft laws on civil registration and gender equality], 20 June 2023, <https://libertas.mk/mpc-oa-povikuva-na-protest-na-29-uni-vo-skop-e-protiv-predlog-zakonite-za-matichna-evidenci-a-i-rodova-ednakvost>, accessed 4 August 2025

Lider.mk, ‘(АНКЕТА) Против уставни измени за внесување на Бугарите во Уставот се 82% од Македонците и 11,3% од Албанците’ [(POLL) 82% of Macedonians and 11.3% of Albanians are against constitutional amendments to include Bulgarians in the Constitution], 6 April 2025, <https://lider.mk/anketa-protiv-ustavni-izmeni-za-vnesuvane-na-bugarite-vo-ustavot-se-82-od-makedontsite-i-11-3-od-albantsite>, accessed 5 August 2025

Macedonia, Republic of, Law on Financing Political Parties, 8 March 2006, Official Gazette of the Republic of Macedonia Nos 36/2006, 76/2004; 86/2008, 161/2008, 96/2009, 148/2011 and 2012), <https://legislationline.org/sites/default/files/documents/ef/2012-11-%2024%20Law%20Financing%20Political%20Parties_en.pdf>, accessed 28 August 2025

—, Law on Civil Registry, The Official Gazette of the Republic of Macedonia Nos 8/95, 38/02, 66/07, 67/09, 13/13, 43/14, 148/15, 27/16 and 64/18 and The Official Gazette of the Republic of North Macedonia No. 14/20, 10 April 2024, <https://www.refworld.org/legal/legislation/natlegbod/1995/en/124335?prevDestination=search&prevPath=/search?keywords=Cyprus%3A+Civil+Registry+Law+%282002%29&sort=score&order=desc&result=result-124335-en>, accessed 28 August 2025

Marusic, S. J., ‘North Macedonia parties close to deal on technical govt’, Balkan Insight, 28 December 2019, <https://balkaninsight.com/2019/12/28/north-macedonia-parties-close-to-deal-on-technical-govt>, accessed 5 August 2025

—, ‘20 Years On, Armed Conflict’s Legacy Endures in North Macedonia’, Balkan Insight, 22 January 2021, <https://balkaninsight.com/2021/01/22/20-years-on-armed-conflicts-legacy-endures-in-north-macedonia>, accessed 12 August 2025

Meta.mk, ‘Music and hatred: How a song caused ethnic tensions at a student party in Skopje’, 15 August 2024, <https://meta.mk/en/music-and-hatred-how-a-song-caused-ethnic-tensions-at-a-student-party-in-skopje>, accessed 5 August 2025

Metamorphosis Foundation, ‘State Funding in North Macedonia: Making the System Fairer, Stronger, and More Transparent’, 2025a, <https://metamorphosis.org.mk/en/izdanija_arhiva/state-funding-in-north-macedonia-making-the-system-fairer-stronger-and-more-transparent>, accessed 5 August 2025

—, ‘Clicks, money and influence: Online media’s roles and responsibilities in elections’, 7 March 2025b, <https://metamorphosis.org.mk/en/aktivnosti_arhiva/clicks-money-and-influence-online-medias-roles-and-responsibilities-in-elections>, accessed 5 August 2025

Micevski, I. and Trpevska, S., ‘Monitoring Media Pluralism in the Digital Era: Application of the Media Pluralism Monitor in the European Union, Albania, Montenegro, Republic of North Macedonia, Serbia & Turkey in the Year 2022’, Country Report: The Republic of North Macedonia, Centre for Media Pluralism and Media Freedom, June 2023, <https://cadmus.eui.eu/server/api/core/bitstreams/c2b70be0-33ec-59a7-98aa-dbe7f39ad7af/content>, accessed 4 August 2025

Mitrevski, G., The Effect of Disinformation and Foreign Influences on the Democratic Processes in North Macedonia in 2023 (Skopje: Metamorphosis Foundation, 2024), <https://metamorphosis.org.mk/en/izdanija_arhiva/the-effect-of-disinformation-and-foreign-influences-on-the-democratic-processes-in-north-macedonia-in-2023>, accessed 5 August 2025

Nikolic, I., ‘North Macedonia: Facebook pages target users with “identical content”’, Balkan Insight, 25 June 2020, <https://balkaninsight.com/2020/06/25/north-macedonia-facebook-pages-target-users-with-identical-content>, accessed 4 August 2025

Open Government Partnership (OGP), ‘North Macedonia Action Plan 2024–2026’, Ministry of Information Society and Administration, February 2024, <https://www.opengovpartnership.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/03/North-Macedonia_Action-Plan_2024-2026_EN.pdf>, accessed 14 August 2025

Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe, Office for Democratic Institutions and Human Rights (OSCE/ODIHR), ‘Republic of North Macedonia, Local Elections, October 2025, ODIHR Needs Assessment Mission Report 24–27 June 2025’, 1 August 2025, <https://www.osce.org/files/f/documents/4/e/595912.pdf>, accessed 28 August 2025

Palloshi Disha, E., Halili, A. and Rustemi, A., ‘Vulnerability to disinformation in relation to political affiliation in North Macedonia’, Media and Communications, 11/2 (2023), pp. 42–52, <https://doi.org/10.17645/mac.v11i2.6381>

Palloshi Disha, E., Sorrells, J., Kreci, V. and Ismaili, V., ‘The prevalence and impact of political disinformation during elections in North Macedonia’, Media Literacy and Academic Research, 8/1 (2025), pp. 208–27, <https://www.mlar.sk/wp-content/uploads/2025/06/11_Edlira-Palloshi-Disha.pdf>, accessed 4 August 2025

Petrovski, I., Ismaili, M., and Kovachevska D., ‘From Levica through Rodina to GROM and MAAK: Who are Moscow’s megaphones in the country’, Truthmeter, 8 April 2024, <https://truthmeter.mk/from-levica-through-rodina-to-grom-and-maak-who-are-moscows-megaphones-in-the-country>, accessed 11 August 2025

press24.mk, ‘ДУИ: Сите се против Албанците – и СДСМ се албанофоби’ [DUI: Everyone is against Albanians – and SDSM are Albanophobes], 10 January 2025, <https://press24.mk/dui-site-se-protiv-albancite-i-sdsm-se-albanofobi>, accessed 11 August 2025

Prezemi Odgovornost, ‘КОГА ЧОВЕК ЌЕ ЈА ЗГРЕШИ ПРОФЕСИЈАТА ЛГБТИ’ [When a person makes a wrong profession LGBTI+... – take responsibility], Facebook, 25 June 2023, <https://www.facebook.com/prezemiodgovornost/posts/pfbid06tYkufMzDxckB1n1GZpXaXLtauWqBfvNCJJcdNNa53RcZAc64sKCs5WetdGQmTaal>, accessed 11 August 2025

Radio Free Europe in Macedonian (RFI), ‘Црквата протестира, власта вели само се дебатира – Што е спорно во законите за „род?’ [The church protests, the government says it’s just a debate—What’s disputable in the ‘gender’ laws?], 27 June 2023, <https://www.slobodnaevropa.mk/a/crkvata-protestira-vlasta-veli-samo-se-debatira-shto-e-sporno-vo-zakonite-za-rod-/32478030.html>, accessed 11 August 2025

Rodina Makedonija, website [n.d.], <https://rodina.org.mk>, accessed 11 August 2025

Ross Arguedas, A., Robertson, C. T., Fletcher, R. and Kelis Nielsen, R., Echo Chambers, Filter Bubbles, and Polarisation: A Literature Review (Oxford: Reuters Institute/The Royal Society, 2022), <https://reutersinstitute.politics.ox.ac.uk/echo-chambers-filter-bubbles-and-polarisation-literature-review>, accessed 11 August 2025

SDSM (Social Democratic Union of Macedonia), ‘History of the Party’ [Macedonian], [n.d.], <https://sdsm.org.mk/sdsm/istorija>, accessed 11 August 2025

Simonovska, M., ‘Russian Disinformation Raising Foggy Anti-Western Sentiment in North Macedonia’, Antidisinfo.net, 11 April 2024, <https://antidisinfo.net/russian-disinformation-raising-foggy-anti-western-sentiment-in-north-macedonia>, accessed 4 August 2025

State Election Commission of the Republic of North Macedonia, ИЗБОРЕН ЗАКОНИК [Electoral Code], April 2024, <https://www.sec.mk/regulativa>, accessed 28 August 2025

Tahiri, S., ‘Public broadcasting service at the service of the citizens of Northern Macedonia’, Goethe Institut, 2021, <https://www.goethe.de/ins/bg/en/kul/sup/med-inc/mi-nm/22511670.html>, accessed 5 August 2025