Designing for Resilience

Building Institutions to Safeguard Information Ecosystems

Democratic societies around the world are contending with unprecedented pressures on their information ecosystems. Foreign and domestic actors are exploiting increasingly sophisticated tactics, techniques and procedures to manipulate public debate, undermine trust, and weaken the key processes and institutions upon which democracy is built. While elections are critical moments for both democracy and its adversaries, informational threats to democracy are not confined to electoral contexts: they permeate societies continuously, eroding cohesion and resilience. Safeguarding democracy and its institutions from foreign interference is thus not just about reacting to crises; it demands a proactive and ongoing effort to enhance institutional foresight and coordination.

This publication approaches that challenge through the perspective of institutional design, suggesting how thoughtful design can help build durable institutions capable of protecting information integrity. Institutions mandated to understand and safeguard national information ecosystems are well placed to act as focal points for democratic resilience in the informational sphere—integrating diverse efforts, bridging silos, and ensuring that responses are coherent, transparent and rooted in democratic values. Such institutions can also serve as connectors across borders, advancing cooperation among like-minded democracies to advance a healthier global information environment for a more democratic world.

The lessons presented in this publication emerge from a comparative and non-prescriptive analysis of different national approaches, recognizing the need to learn from global practice and unify international processes. Even if no single model ought to be replicated wholesale worldwide, the report reveals common principles that can and should guide institutional development. These include independence, pluralism, transparency and inclusivity.

By embedding these principles into institutional design from the outset, democracies can strengthen both the legitimacy and the effectiveness of their responses to informational threats. In doing so, democracies will not only enhance their national security but will simultaneously help to cultivate public trust, protect human rights and ensure that citizens remain able to make informed choices about their future without interference from foreign actors.

This discussion paper will serve as a valuable resource for policymakers, practitioners and civil society stakeholders in the global struggle to protect democracy from foreign interference. By learning from each other’s experiences, aligning around shared democratic principles and investing in institutional resilience from design to delivery, democracies can safeguard the information ecosystems on which they, and we, depend.

Dr Kevin Casas-Zamora

Secretary-General, International IDEA

Information threats to democratic societies and processes, particularly before and during elections, have become a growing concern for policymakers and citizens worldwide. Malign influence campaigns by state and non-state actors, which span cyber, economic, political and information activities, are becoming increasingly sophisticated. By targeting individual and collective decision making and undermining the integrity of national information ecosystems, these campaigns have contributed to erosion of trust and political polarization. Democratic governments around the world have responded by setting up institutions and policies, while civil society organizations have implemented programmes to detect, prevent and mitigate these attacks on democracy. Media, experts and awareness campaigns have also contributed to the fight by raising public awareness of these threats and the need to enhance systemic resilience, particularly in the context of decision making. It should be noted that national responses vary widely, reflecting different contexts, legal traditions, political priorities and levels of institutional capacity.

Nevertheless, despite numerous and varied mitigating efforts to date, democratic governments and societies continue to struggle to mount effective responses to these campaigns and operations. Divided by operational silos, varying degrees of understanding or capacity, financial pressures and lack of political will, among other factors, many domestic and international stakeholders are growing impatient and frustrated about the absence of robust progress. Shifting political priorities in some Western countries have only exacerbated the situation, with funding and policy support for government- and civil society-led initiatives to promote resilience and capacity building being significantly scaled back. Alongside numerous challenges, however, this new operational environment presents an opportunity to reassess the approaches that have been implemented so far and consider alternative paths.

This discussion paper argues that democratic societies and governments must take a more coordinated, more systemic, better organized approach to dealing with information threats. These continuously evolving threats affect democracies beyond electoral cycles or key national events. They pose interrelated social, political, economic and security challenges that cannot be addressed by a single agency or government, even if said agency or government enjoys significant collaboration with civil society and other stakeholders. The scale and compounding impact of information attacks will slowly degrade the integrity of national information ecosystems, undermining the cornerstone of democratic processes—individual decision making. As such, the approach to addressing existing information threats and developing greater resilience to as yet unknown or emerging ones must be equally systemic. Democracies must build on lessons learned from past experiences and existing institutional examples in countries that have advanced further on this path, adopting a more mature, whole-of-society approach.

Enhancing domestic resilience and improving responses will require dedicated mechanisms to integrate and champion disparate activities at the strategic, operational and political levels. A national institution dedicated to improving collective understanding of information ecosystem challenges, forging systemic relations and providing recommendations could feasibly act as a focal point. Constituted as part of a coherent national framework to safeguard the integrity of the relevant information ecosystem, including its security, such an institution could bridge gaps across operational mandates. As a public and trusted organization acting at arm’s length from the executive branch, it would also be ideally positioned to mobilize whole-of-society efforts to safeguard shared democratic values and objectives. As well as shaping this approach domestically, this institution could also advance international coordination with other like-minded countries, especially across societies that implement similar processes. Given that they are facing similar challenges and threats, democracies need to build a new coalition—one that facilitates the evolution of a whole-of-democracy approach to information threats, both existing and emerging.

This discussion paper offers a mapping of key elements which decision and policymakers, as well as prospective domestic stakeholders, may need to navigate when considering how to improve current approaches. Building on open-source materials, previous experience and interviews with public officials, it highlights relevant practices, challenges and potential unintended consequences. As institution building is a highly context-specific process, it is difficult to provide detailed, practical recommendations that could be implemented across the board. Subsequent analyses and discussions could pick up this thread. Instead, the following points summarize key observations stemming from the analysis:

- Information threats and risks will continue to evolve alongside technological developments and as part of the adversarial toolbox in the information age.

- Each society possesses a unique socio-political context that informs its approach to information threats. Despite common values, it is difficult to replicate a good practice from one democracy to another, unless it is technical or procedural in nature.

- A national approach to countering information threats must be based on an improved understanding of the national information ecosystem, which goes beyond traditional and social media. This can be achieved through regular analysis of the factors and trends that shape the ecosystem.

- To increase their resilience, democracies need to build on current threat-based approaches, developing a proactive and holistic vision of what a healthy national information ecosystem looks like. This vision could then become the basis of a national framework, inform the development of relevant plans and guide stakeholder engagement strategies.

- A whole-of-society approach to countering information threats and building resilience is impossible without involving trusted civil society partners in the planning and delivery of critical functions.

- A dedicated national public institution is required to act as a focal point for coordination, research, and capacity and awareness building, as well as to facilitate collaborative solutions that strengthen resilience in a transparent and accountable manner.

- By following a similar core institutional blueprint, democracies could improve interoperability, coordinate more effectively and enhance the effect of actions taken, both at home and abroad.

In recent decades, national information ecosystems have become highly contested arenas of competition between state and non-state actors, for attention, political power or profit. These actors target democratic institutions and processes, political leaders, facts and marginalized groups, deploying various forms of information manipulation tactics. While the visibility of these harmful activities rises during election cycles, ample evidence points to continuous and often coordinated campaigns, spanning borders and involving a multitude of foreign and domestic stakeholders. By rapidly deploying emerging technologies, including generative AI tools, malign actors have increased the speed and reach with which they create and disseminate false or misleading content, as well as making it more convincing (Chenrose and Rizzuto 2025). The observed proliferation of manipulated or false information during emergencies, such as the Covid-19 pandemic, and electoral cycles has contributed to an erosion of trust in governance systems, fomented discord and divisions, and undermined public health initiatives (Heinmaa 2023; FIMI–ISAC 2024). Due to severe repercussions for domestic stability and governance, the threat of coordinated information campaigns to individual and institutional decision making emerged as a top political and security concern across many democracies. The increasing awareness of these threats has highlighted that cultural, linguistic, socio-political, geopolitical and economic factors not only shape how manipulated information impacts individuals and groups but also inform the political and organizational dimensions of responses.

These developments have galvanized many countries to adopt protective measures, including limiting harmful content, imposing sanctions on malicious actors, regulating social media platforms and improving domestic resilience (Asplund and Casentini 2024; Keller, Freihse and Berger 2024; Zimonjic 2025). Civil society organizations have also been endeavouring to promote awareness, highlight factual information and target perpetrators at their source. Still, despite these and many other efforts, neither the scale nor the level of threat has abated. Mounting evidence from different experiences has led to campaigns to improve awareness, while also exposing numerous gaps at all levels of governing institutions and society. Increasingly, democratic information ecosystems are being recognized as complex, open systems, which need to be managed more holistically. Management approaches must bridge functional silos, improving government coordination, information sharing and strategic communication. At the same time, they also need to integrate all willing national stakeholders, in a whole-of-society manner, to effectively improve resilience.1 This, understandably, poses numerous challenges for existing processes and complex institutional relationships of political compromise and accommodation which have been developed over decades, if not centuries. As of yet, no ‘off-the-shelf’ model, which can be readily tailored and implemented, has emerged.

This does not mean that democracies are failing. The need to maintain open and vibrant societies, based on consensus and preservation of individual rights and freedoms, poses unique challenges. These challenges span conceptual, strategic and operational layers, as well as foundational issues of governance, power and identity, among many others. The approaches adopted to date in different countries have varied considerably in terms of their mandates, degrees of engagement with domestic stakeholders and prioritization of steps. Some countries emphasized transparency and building public engagement from the bottom up, while others relied more on national security-led and intelligence-led countermeasures with limited public visibility. Understanding these diverse approaches to combating information manipulation is critical for policymakers as they seek to build their respective national frameworks and manage stakeholder expectations.

This discussion paper is based, in part, on an examination of institutional choices made by France, Moldova, Spain and Sweden since 2018 through publicly available information, documents and interviews with relevant officials. In each case, the path adopted by the respective national mechanisms reflects a unique set of challenges, conditions and options pertaining to their contexts. Because of their relevance to this discussion, we have included these case studies (see the boxes in Chapter 3) to briefly illustrate distinct approaches implemented so far. These are intended as examples only. The continued evolution of these respective processes, each with distinct dynamics, challenges, lessons and solutions, makes it difficult to speak of readily transferable good practices, beyond very technical issues. These experiences, however, allow practitioners to make numerous observations, some of which are synthesized as a possible path forward in this paper. Subject to unique national contexts, the institutional design perspective discussed here offers democracies an opportunity to navigate their way through known political and organizational tensions—for example, between domestic and foreign mandates, between safeguarding electoral integrity and ensuring freedom of expression, and between open democratic debate and the need for security-driven interventions. By focusing on resilience, transparent processes and engagement with key stakeholder communities, a more mature approach to dealing with information threats could emerge.

As such, this discussion paper will be of interest to a broad range of actors—including policymakers, institutional leaders, researchers and civil society practitioners across government, corporate, academic and civic sectors—who have invested significant efforts and resources to address information threats. National information ecosystems are inherently systemic, and so all solutions must be contemplated by all relevant stakeholders from a whole-of-society perspective. This requires the establishment of a proactive vision for what a healthy information ecosystem should look like, meaningful enough to serve as a goalpost for individual decision making and the sustainable evolution of a society. This could then be supported by a national framework, consultations and legislative and operational actions. It is hoped that this paper will help shape a more collaborative stance among diverse stakeholders, both domestically and internationally.

At the same time, we believe it is important to set expectations for what this paper is not. Given the topic’s complexity and the different starting positions held by democracies, the path towards a possible shared future will not be the same for every country. This is why in this paper we avoid taking a prescriptive approach. Instead, each section in Chapter 3 introduces questions that will prompt exploration of specific measures that may or may not align with a democracy’s normative and socio-political contexts. As they are facing similar threats and challenges, democracies may pursue national institution-building processes, while also exchanging information and coordinating between themselves. The box outlining a theory of change for democracies provides further clarity on how domestic and international coordination efforts could align, amplifying each other’s effects. Democracies have the choice to pursue national processes that contribute to a common greater good. This discussion paper aims to offer general contours of how this can be accomplished.

The highly interconnected global information environment links individuals and societies across borders. It offers new knowledge and opportunities but also generates new risks and threats. In recent decades, increasing attention has been given to the role of information, its creation, its dissemination and especially its impact on decision making in the political, economic and social spheres. The ability of individuals to make informed, independent decisions about their futures has been traditionally regarded as a cornerstone of democracy.

Human rights are predicated on the existence of conditions that enable them. These include access to accurate information, free media, transparent sources, digital literacy and the ability to make independent choices, including through elected representatives. How these conditions evolve in each national context depends on its rules, norms and institutions, but also on citizens’ awareness and understanding of their shared reality. This shared perception of reality is what ultimately shapes individual choices, and by extent public policies, regulations, norms and expectations. These and many other factors impact the prosperity, stability and, if necessary, survival of a society. Constructed through an intricate, now technology-enabled network of information-driven processes and relationships across families, communities and organizations, this reality manifests itself as a national information ecosystem—a highly dynamic and adaptive domain.

In democracies, information ecosystems are largely shared and open spaces that constantly evolve subject to input (e.g. social media posts, marketing, news, political ads, rumours and falsehoods) by various actors, including foreign adversaries, alongside enabling conditions that influence their behaviour and dynamics (e.g. regulations, infrastructure, ownership, norms). While information ecosystems have existed as networks of information exchange since the dawn of human existence, their complexity and the speed with which they are evolving have dramatically increased since the adoption of the Internet. The rapidly changing conditions and uneven exposure to information across decision-making layers are exerting significant stress on individuals and organizations trying to make sense of their realities. Structuring and managing information flows for socially meaningful purposes, all while striving for broad democratic consensus, is also becoming increasingly difficult. When degrading quality of information or inability to achieve desired outputs begin to wear down this complex ecosystem, the ability of a society to guarantee its continuity greatly diminishes (OECD 2024a).

In recent years, the quality of these inputs and conditions, as well as trust between critical nodes of social networks, have increasingly come under attack from foreign and domestic actors. Hybrid operations by foreign state actors,2 disinformation campaigns by extremist or radical groups, assaults on the integrity of critical information infrastructure and online fraud, among other activities, all threaten national interests and social stability (VIGINUM 2025; Sicurella and Morača 2025). These operations occur across different layers—cognitive, psychological, technological, physical—while affecting our individual and collective realities and decision-making processes in different ways. Crossing national boundaries, the snowballing scale and scope of these activities undermine public trust in institutions, procedures and overall governance systems. Citizens in many democracies are already facing tough socio-economic choices, and so the injection of inauthentic or false content, for example, may further erode their ability to make independent yet informed decisions. Furthermore, these activities often aim to weaken social cohesion and capacity to pursue effective policies. Since the 2016 United States presidential election, a significant amount of evidence has accumulated which suggests that foreign actors and their proxies interfere in elections and other events by exploiting states’ systemic and institutional vulnerabilities (EEAS 2025; McPherson 2025). For example, Russian information operations extend beyond the borders of a particular country and occur on a continuous basis, especially in countries Russia deems of strategic importance (Châtelet and Lesplingart 2025). Other state actors, such as China and Iran, have also ramped up their respective disinformation and influence campaigns in recent years (Charon and Jeangène Vilmer 2021; ODNI, FBI and CISA 2024). Malign actors, ranging from states to extremist social movements to corporations, use multiple digital technologies and techniques to influence election outcomes, advance social agendas or manipulate citizens’ perceptions of domestic and foreign policy issues (Wanless and Berk 2019; Bicu n.d.).

Despite increasing awareness of these threats across democratic societies, different individuals may perceive them in different ways. Many factors—such as cultural and political norms, social structure and cohesiveness, education levels, and conditions such as geography, military strength and socio-economic development—influence how societies interpret these threats and their possible impact. The varying weight of these factors in each specific context, in turn, directly affects how citizens, civil society organizations and decision makers frame the national discourse and conceive possible responses. Furthermore, even in jurisdictions which have an elevated societal awareness of information threats, the responses to date have varied in scope and focus. Invariably, decisions regarding possible courses of action are influenced by the lens through which decision makers examine public issues and weigh risks. For example, national responses to foreign interference may vary in relation to its impacts (e.g. economic coercion, corruption, erosion of truth and facts, or espionage), the actors involved (e.g. foreign countries, proxies, criminal networks), the content (e.g. inauthentic messages, disinformation) and associated behaviours.

Consequently, and in the absence of binding international laws or universally accepted norms that outline responsible behaviour in the information environment (beyond cyberspace), different countries conceptualize and respond to these threats differently. This results in mandates and mechanisms that usually focus on a narrowly defined set of malign actors, factors or conditions behind a threat. In many democracies, this process includes monitoring of open sources, information sharing and coordination among security and intelligence agencies, with varying degrees of engagement with civil society, experts and media. As both information threats and national ecosystems constantly evolve, adding new mechanisms compounds coordination pressures and demands new resources.

This in turn poses two significant, and interrelated, dilemmas in democracies. First, the securitization of issues pertaining to the national information ecosystem—which is warranted, especially in cases involving foreign actors—increases the security apparatus while limiting collaborative engagement with non-government sectors. This, in turn, thwarts a whole-of-society response and societal resilience, both of which are predicated on citizens’ engagement. This is especially evident in polarized societies which have lower levels of trust in governing institutions and media. A possible slide towards authoritarian measures in certain circumstances presents a real danger to democratic values. Second, viewing information ecosystem challenges mostly through a threat-focused lens constrains the range of possible non-security solutions to systemic vulnerabilities and risks affecting the whole of society. Strengthening multicultural ties among citizens, improving youth employment opportunities and envisioning national projects that also contribute to building tolerance, mutual understanding and cooperative spirit among the population are more likely to result in stronger resilience to foreign interference. In addition to these domestic challenges, and despite current international coordination efforts, democracies largely differ in the degree to which they acknowledge existing barriers and gaps. This, in turn, affects prioritization of resources and the ability of countries to mount ‘whole-of-democracy’ responses to different forms of information manipulation and interference (e.g. the countries of the Global South have experienced challenges with supporting Ukraine’s resistance to the Russian invasion).

To confront these interrelated social, political, economic and security challenges, democratic societies need to develop a more mature approach to information threats and risks. This has already been acknowledged in several recent calls for action by international organizations and democratic governments (OECD 2022; Government of Canada, Government of the USA and Government of the United Kingdom 2024). Built on systemic recognition of what constitutes a national information ecosystem, the approach must be founded on a proactive vision that captivates attention and mobilizes engagement across stakeholder communities—for example, by developing and implementing the concept of digital citizenship (Council of Europe n.d.; OECD n.d.b; United States Department of State n.d.). To ensure that citizens can pursue their objectives in a safe and secure democratic environment, there is also a need for relevant institutional infrastructure which is capable of addressing specific incidents and fostering the conditions that support a healthier domestic information ecosystem.

Institutions are designed to play a critical role in democracies on different levels. Strategically, they ensure the predictable functioning of the political system by empowering and constraining government, upholding citizen rights and promoting a healthy democratic culture. Operationally, they achieve these objectives through different means, including by managing and channelling relevant information through established protocols and procedures to ensure the system’s continuity. Socially and politically, institutions are needed to facilitate collective decisions, enforce rules and inform expected behavioural norms. For example, most democratic states have electoral commissions and supporting state agencies that oversee voting processes and enforce legal regulations surrounding campaign tactics, campaign funding and fair access to broadcast media. Other state institutions protect civic and political rights that are necessary for political participation, such as freedom of expression and association.

In the face of numerous systemic challenges in the information domain, different democracies have mounted a range of responses in recent years, reflecting varied contexts, legal traditions, political priorities and levels of institutional capacity. Some countries have established dedicated agencies to counter disinformation and foreign malign influence, while others have integrated these responsibilities into existing electoral commissions, foreign ministries or national security apparatus. Many countries have established mechanisms to explore or advance cross-institutional responses in various forms. Further regulatory, media and civil society initiatives have also contributed to raising societal awareness about threats and their possible impact on societies (Sessa et al. 2024).3

Still, despite these numerous and diverse efforts, democracies continue to struggle with political and security risks stemming from coordinated campaigns by harmful actors. Awareness has not spread consistently across different stakeholder groups, while content regulation and calls to uphold ‘truth’ have backfired due to allegations of government surveillance or encroachment on basic freedoms. The long-term impact on societies of other efforts, such as fact-checking, pre-bunking or countering malign campaigns by improving strategic communications, also remains unclear beyond limited-scope experiments and cases. The multitude, diversity and range of attempted efforts to date, when assessed in relation to the systemic nature of information threats, prompted some experts to dub them ‘whack-a-mole’ strategies (Bradshaw 2020; Johnson 2024). This is not to say that these efforts were for naught. Democracies have achieved significant strides in terms of understanding information threats and recognizing the need to address them as a top priority. Moving forwards, it is important that they conduct a frank review of lessons learned and translate the resulting knowledge from these experiences into a new, more mature approach to safeguarding national information ecosystems and addressing emerging threats. To get where they need to go, democracies need a new system that organizes and channels disparate efforts with greater coherence.

In social systems, information attacks seek to exploit psychological and cognitive vulnerabilities in how people receive, interpret and act on information (Giannopoulos, Smith and Theocharidou 2021; NATO 2025). By targeting individual decisions and behaviours, these attacks aim to undermine the social relationships that underpin collective socio-political and economic stability, especially during crises and conflicts. This is why societal resilience to information threats is so paramount. At a societal level, resilience requires cohesion among its members, reflected in a sense of community, identity, belonging and trust that drives cooperative and constructive action, especially during times of stress.

Bearing this perspective in mind, dedicated mechanisms to integrate and champion disparate activities at the strategic, operational and political levels are required to advance towards resilient democratic societies. One possible next step could be to create a national institution dedicated to improving collective understanding and awareness of information ecosystem challenges, forging systemic relations across stakeholder communities and providing policy and practical recommendations. Constituted as part of a coherent national framework to safeguard the integrity of the information ecosystem, including its security, this public institution would bridge gaps across operational mandates and mobilize whole-of-society efforts to support shared democratic values and objectives.4

Above all other learning or coordination functions, this institution’s key role would be to identify and encourage processes that lead citizens and organizations to develop identities and behaviours that support a shared public good—a healthy national information ecosystem. By aggregating evidence through research and assessments and engaging wider expert communities in a transparent and collaborative manner, such a national institution, under the right framing and conditions, could emerge as a trusted, accountable authority acting on behalf of and for the public benefit of informed citizens. In pursuing this path towards institutionalizing and codifying relevant processes and behaviours, democracies would simultaneously be able to establish safeguards against partisan ideological interference and raise procedural barriers against authoritarianism.

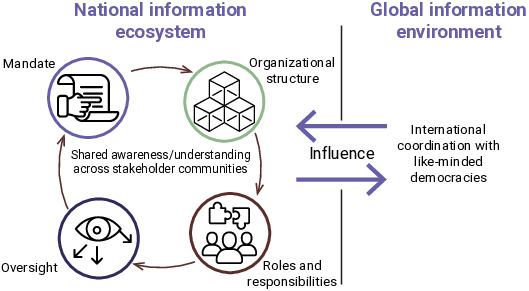

This chapter outlines key elements that policymakers should consider when designing institutional responses to information threats, drawing on both practical experiences and insights from interviews with public officials who have led relevant efforts in their respective jurisdictions. It also includes four boxes featuring cases from Sweden, Spain, France and Moldova, whose governments pioneered institution-building processes in recent years. Given that these initiatives continue to evolve, subject to constraints and opportunities, the inclusion of these cases should not necessarily be interpreted as endorsements, but rather as examples only. Institution building is a highly context-dependent and politically sensitive process, and so it is difficult to extrapolate whether something that works ‘here’ will apply ‘there’. This is why basing national approaches on individual best practices trialled and adopted elsewhere, beyond very technical or procedural matters, may yield an unsatisfactory or different outcome. Instead, the general provisions discussed here offer an opportunity for democracies to envision a common path first. Then, the vision and blueprint discussed here could be complemented by a customized application of methods and processes tried elsewhere, if required. Apart from facilitating a more coherent evolution of respective national approaches across mandates, having a common blueprint should enable democracies to conduct more open discussions about key challenges, questions and dilemmas which need to be addressed. While they may hold diverse views on threats or ecosystem conditions, they are more likely to advance towards greater coordination and collaboration if they share a similar, interoperable vision. This can guide the continuing alignment of processes over time, as capacities and capabilities improve (see Figure 3.1).

3.1. Shared awareness and understanding

Before discussing key elements of institutional design, it is crucial to address a fundamental issue that underpins both societal resilience to threats and a whole-of-society approach to responses. In all emerging approaches examined for this paper, the presence of ‘shared awareness’ was highlighted as a key foundational element, and its absence as the most significant obstacle. Notwithstanding mandates or structures implemented to date, all jurisdictions encountered similar operational, organizational and strategic challenges that can be attributed to different degrees of awareness and understanding of threats, terminologies, policies or available options. A coherent national framework and approach will struggle to emerge if organizations across government, civil society, academic and industry communities continue to operate at varying wavelengths.

Currently, increasing awareness in relation to information threats is understood primarily as an improved level of public mindfulness regarding mis- and disinformation campaigns or cyber phishing and possible protective behaviours. Delivered through strategic communications campaigns (mostly top-down), digital literacy efforts or media coverage, these activities aim to bring citizens’ passive attention to harmful phenomena and possible countermeasures.

The likelihood of changing individual cognitive and behavioural patterns through these efforts depends primarily on how much citizens are exposed to such information, followed by individual receptivity. While the impact of these methods can be debated, it must be acknowledged that, despite many efforts, perceptions of information threats inside and across democratic societies vary considerably. This, of course, applies to all stakeholder communities, including government agencies, where narrowly defined mandates shape how decision makers understand their operational environment and available options. In highly polarized and fragmented information ecosystems, with low levels of trust in governing mechanisms, these perception gaps about threat actors, their impact and possible responses cause significant policy and political challenges.

Moving beyond this threat-based approach, democracies need to cultivate broader concepts of what it means to proactively build and protect their respective information ecosystems, such as national information integrity. Such concepts must be sufficiently broad to act as an overarching strategic policy umbrella for many mandates and carry a multigenerational appeal around which different socio-political and cultural narratives can emerge. By transcending narrow policy mandates or political agendas, such concepts are more likely to mobilize a whole-of-society approach and advance societal resilience in the long run (Council of Europe Committee on Political Affairs and Democracy 2025).

Adopting such concepts would also enable democracies to advance towards two equally critical objectives: first, to establish long-term, strategic national development goalposts against which everyone can measure their progress; and second, to guide more immediate policy planning and operational response implementation, bridging gaps between current and future realities. As a first step in this direction, societies need to develop a shared positive vision of what a robust information ecosystem, built on democratic values and principles, might look like. Aside from outlining general aspirational objectives, this process would provide stakeholders with more operational direction regarding which social, economic, cultural and security conditions, among others, must be pursued through policy development and targeted funding. If conducted in a transparent and sincere fashion, national public consultations on these issues could promote a shared understanding of possible futures, encompassing issues of identity, prosperity, security, rule of law, justice and freedom, among others. Furthermore, this process could feasibly transform into an inspiring and mobilizing activity that reinforces a sense of belonging and community building.

Questions pertaining to the systemic role of a healthy information ecosystem in all these issues, options to achieve it, and gaps and threats should underlie this discussion. The outcomes of this process could be used by all national stakeholders to advance multiple practical objectives, from ingraining accepted behavioural norms to defining parameters for politically acceptable policies and regulatory mechanisms—and much more. A shared normative and value base is indispensable in any society wishing to pursue relevant social, political, economic or defence objectives in a stable and coherent manner.5

Indeed, in certain contexts, it might not be possible to pursue this path due to high levels of societal polarization, low trust in media and government or other conditions, such as open conflicts. In these instances, leaders may feel pressured and so opt for expediency, addressing information threats through mechanisms like legislative acts, executive orders or strategic communication. Nevertheless, taking this course of action in a democracy is fraught with significant perils in the long run. At a minimum, it must be accompanied by clear and transparent communication regarding objectives and timelines. It is useful to remember that attacks on information integrity often target the same media, non-governmental organizations (NGOs) and processes that form the backbone of democratic resilience and rule of law. As they directly feel the adverse effects of influence campaigns, these organizations may not only possess heightened awareness of threats but also become the strongest partners in defending against them.

In any scenario, a mature approach that recognizes the holistic impact of information ecosystems on the whole of society must also seek to develop practical initiatives that enhance both resilience and policy development. In many ways, the national information ecosystem should be perceived as new critical infrastructure on which the sustainable development of modern societies is predicated. Building societal resilience to withstand and quickly rebound from information shocks is, of course, more than just bricks and mortar. It is a complex socio-political process that starts with all stakeholders acquiring shared knowledge about how the laws, regulations and interventions they pursue will impact the national information ecosystem over time. In essence, no system can persist or rebound without knowing its critical characteristics. And this knowledge can only emerge through an organized and coordinated effort to assess socio-political, economic and other relevant factors that impact how national information ecosystems evolve over time (Wanless, Lai and Hicks 2025). Fostering this evidence-based common understanding across as wide a community of decision makers as possible could contribute to dismantling the current barriers facing policymakers and responders. More importantly, perhaps, this analysis, backed up by systematic evidence, could also inform the evolution of individual and national identities, as well as encouraging citizens to engage in shaping and defending their societies, in line with democratic principles. Active participation by civil society members in representative deliberative processes will likely enhance checks and balances, increase accountability and transparency, and trust in democratic processes and institutions. All these effects will bolster societal resilience (OECD 2020).

Questions to consider regarding shared awareness and understanding:

- Who are the key national actors and stakeholders (e.g. specific groups, departments, associations, media entities, industry players) on information ecosystem issues, and what roles do they play?

- How can the institution promote shared language and conceptual clarity across divergent stakeholder perceptions in a way that helps each of them to identify their role and responsibilities as part of a national effort?

- What mechanisms and approaches could foster a shared situational awareness of trends in the national information ecosystem, including threats, risks and vulnerabilities? What role should the institution play in scenario planning or early warning systems?

- What kinds of data, evidence, intelligence or expertise should be prioritized to support shared awareness?

Box 3.1. Swedish Psychological Defence Agency

The Swedish Psychological Defence Agency (Myndigheten för psykologiskt försvar, SPDA) safeguards Sweden’s open and democratic society and the free formation of opinion by identifying, analysing and countering foreign malign influence, disinformation and other misleading information directed at Sweden or at Swedish interests (SPDA n.d.).

Established in January 2022 as a government agency under the Ministry of Defence, the main mission of the SPDA is to lead the coordination and development of Sweden’s psychological defence, in collaboration with public authorities and other societal stakeholders. Recognizing the importance of a whole-of-society approach to resilience and defence, the SPDA supports government agencies, municipalities, regions, business sector stakeholders and organizations to strengthen the capacity of Sweden’s population to resist and respond to information threats. This approach has been built in partnership with several agencies, drawing on the multigenerational legacy of fostering psychological defence during the Cold War.

The SPDA works to raise societal awareness, establish a common operational language and embed shared practices through research reports, handbooks, training courses, cooperation with civil society, educational films and media literacy. These efforts are aimed at motivating all relevant stakeholders to raise Swedish society’s preparedness ahead of any threats or crises. The SPDA also cooperates with international partners to share information about threats and evaluate outcomes and best practices (Tofvesson and Kozłowski 2024).

3.2. Mandate

Defining the scope and authority of an institution aiming both to safeguard the national information ecosystem and advance its evolution in line with democratic values represents a critical political decision point. Which authority grants the mandate and for what purpose? What priorities and responsibilities will it cover? Would new legislation be required? How does it ensure the mandate stays relevant in the face of changing realities?

Due to varying cultural, social and political contexts, the responses to these and related questions will be answered differently across democracies. As of now, despite several examples that offer meaningful lessons, no comprehensive model exists that could be readily copied elsewhere. At the same time, there are common principles, such as a will to protect democratic rights and freedoms, strong public oversight, transparency and accountability, independence from the executive branch and a whole-of-society approach, which offer strong foundations for enhancing citizens’ trust in democratic governance and fostering international collaboration and coordination.

In most existing cases, national institutions or initiatives have emerged because of the decisions of the country’s central government. In recognition of emerging and rapidly evolving information threats, these governments have moved to establish capabilities to monitor and coordinate relevant activities in a whole-of-government fashion. Highly operational in nature, these initiatives focus primarily on identifying specific threats, while also enhancing coordination with other relevant stakeholders to reduce or mitigate their impact.

Based on the interviews conducted for this paper and drawing from prior experience in this field, two key challenges appear to be facing most democratic governments at this juncture. First, government agencies do not naturally share information and analysis in a truly integrated way. Issue-based legislation and separation of authorities alongside varying degrees of awareness often present barriers to whole-of-government action. Divided by siloed mandates, the best practice currently is to coordinate through interdepartmental task forces built around single issues. Nevertheless, due to varying policy and operational needs, the resulting recommendations and response options are often based on the lowest common denominator, unless a strong political directive exists. This narrow functional approach often struggles to provide answers in a complex and rapidly changing environment. Second, is the challenge of converting the outcomes of political and government decisions into processes that motivate and mobilize citizens towards shared objectives, such as constructing and securing resilient information ecosystems.

It is time to envision a different approach which integrates key responsibilities to support broader societal resilience, while facilitating a more flexible whole-of-society approach. Without duplicating operational response functions that are already performed by government agencies, a national institution legislated by parliament could serve as a crucial pillar of a critical (democratic) infrastructure (see 3.3: Roles and responsibilities), connecting diverse threads across the nation. Its mandate and key functions could include directing knowledge and evidence development to improve understanding of the national information ecosystem conditions (including threats and risks); developing a whole-of-society approach through consultations and development of norms; delivering standardized capacity building; identifying and pre-empting emerging problems by marshalling resources and expertise; and working across government, industry and non-government communities to enhance the integrity and resilience of the information ecosystem through regulation and comprehensive policy recommendations. As such, this institution would act as the ‘glue’ connecting the horizontal and vertical axes of policymaking and practice.

Three popular conceptual frameworks that are often deployed in democracies to address emerging threats in the information environment are presented below. This brief analysis may be relevant to readers as they contemplate various national approaches, including mandates.

3.2.1. National security

In the context of foreign interference operations, many democracies share similar concerns about undue influence by radicalized or extremist groups, state-sponsored attempts to sway politicians, cyberattacks on critical infrastructure or election security being compromised. By legitimately framing these malign activities as national security threats, political authorities and governments traditionally pursue two interrelated courses of action. First, they attempt to raise public awareness of emerging threats and galvanize public opinion in support of government policies and actions. These actions often centre on monitoring and surveillance activities, intelligence sharing and law enforcement efforts, which are in turn supported through relevant legal and regulatory measures. Strategic communications also constitute an important part of these efforts. Second, governments move to either establish new or reorganize existing mechanisms dedicated to addressing threats—these efforts are often siloed given the associated technical, policy and operational needs pertaining to the scale and scope of the perceived problem.

This functional, threat-based approach allows governments to pursue traditional methods of protecting national security. Existing regulatory frameworks, mandates and processes are applied to new security concerns, while capability and other gaps are augmented, as required. Nevertheless, as demonstrated by emerging evidence, this approach is facing significant challenges in the following areas:

- Conceptual. Addressing one or more information-based challenges in isolation clashes with the systemic nature of a modern information environment.

- Strategic. A reactive, threat-based approach impedes the development of a holistic, proactive and mobilizing vision that is capable of shaping the national information ecosystem in line with democratic values and principles.

- Operational. While improving some functions, the approach may also increase institutional barriers (e.g. judicial review) and transactional costs (e.g. coordination), affecting the impact and efficiency of the administration.

- Societal. It might be difficult to galvanize public support and participation due to existing societal polarization and low trust levels in existing governing institutions and media.

3.2.2. Total defence

Predominantly adopted across the Nordic countries of Europe, but also in Singapore and Switzerland, this concept integrates whole-of-society and whole-of-government approaches to national security and defence against threats (Nicholson et al. 2021; Berndtsson 2024; Palmertz et al. 2024). Emphasizing domestic preparedness and resilience to military and non-military challenges, the concept takes a systemic perspective on organizing a country’s resources and capabilities. Focus is placed on fostering a population’s will to resist and fight back, if required, which translates into forging a sense of shared reality and purpose among all stakeholders, including individuals, companies and all levels of government. While threats and risks can manifest themselves in many unpredictable ways (e.g. natural disasters, pandemics or hybrid attacks), the ability of a society to ensure continuity of services and survival is predicated on the psychological readiness of its citizens.

By taking a more systemic and strategic outlook, this concept paves the way for developing relevant narratives, processes, capabilities and regulations, while at the same time engaging and motivating the whole of society. In doing so, the total defence concept aims to bridge gaps between organizational, institutional and motivational needs while also offering an opportunity to establish generational and nation- and identity-building objectives. It must be noted, however, that many jurisdictions pursuing this path already possess a higher degree of societal cohesiveness either due to their historically developed sense of shared identity or ability to instrumentalize existing geopolitical or security conditions, alongside cultural and social norms to support this. It will be more challenging to implement this concept in multicultural democratic societies where citizens possess varying perceptions of information threats or divergent visions of social and political priorities more broadly.

3.2.3. Information integrity

A more recent holistic concept that focuses on establishing and promoting healthy information ecosystems through coordinated actions has emerged out of the United Nations. Recognizing the negative impact of manipulated or low-quality information on individual choices, freedoms, privacy and safety, the UN proposed an outline of a future global vision and recommendations for various national stakeholders (United Nations n.d.; Bentzen 2024); The concept was further developed through several government- and international organization-led initiatives that have encouraged stakeholders to commit to good practices with regard to digital policies, platform governance, domestic resilience and countering disinformation (Government of Canada 2024; OECD 2024b).

Building national information ecosystems that are based on accurate, consistent, reliable and secure information to enable both individual and organizational decision making represents a visionary idea in the Information Age. As a shared goalpost, this concept could be operationalized to provide individuals, organizations and decision makers with meaningful guidelines to measure their individual and institutional performances. Notably, the UN Development Programme has developed several manuals and frameworks that are designed to defend the integrity of information during electoral cycles and beyond (UNDP Policy Centre for Governance n.d.). The concept could also be feasibly integrated with existing public security and national emergency management frameworks (linking to the total defence approach) (Adam et al. 2023). Since the global information environment is shared by all, this concept has the greatest potential of tying domestic development and national security issues to a more universal agenda of ‘global public good’, based on strong commitments to human rights, democratic values and principles. This potential could be transformed into tangible national frameworks through awareness building and development of practical recommendations, based on information ecosystem analysis and stakeholder consultations.

Box 3.2. Spain’s national effort to counter disinformation

Recognizing the threat to national security and society, in 2019 Spain established a national structure under the presidency to develop and coordinate national efforts (Government of Spain 2020). Led by the Department of National Security (Departamento de Seguridad Nacional, DSN), and operating as the Standing Committee against Disinformation, this mechanism integrates efforts from different government agencies to identify disinformation campaigns, inform the public, support government decision making on relevant issues and coordinate national responses. This approach promotes the exchange of information between agencies with responsibility for detection, analysis, communication and diplomacy, as well as allowing representatives to foster working-level collaboration, including during events with elevated risks of foreign interference, such as elections.

These domestic efforts are evolving in alignment with relevant European Union initiatives, strategically and operationally. For example, the government recently adopted a decision to develop a comprehensive national strategy to combat disinformation, including measures such as receiving public proposals on how to combat disinformation (Government of Spain 2022). Building on EU guidelines and, specifically, on the 2020 European Democracy Action Plan, the decision outlines key roles and expectations for a robust national strategy that is based on contextual analysis and evidence and also aims to ‘[reach] the broadest possible consensus among the actors involved’.

Recognizing that engaging with civil society, media and other stakeholders is key to domestic resilience, the DSN has been pursuing various private–public partnerships through consultations, supporting research and more (Government of Spain 2025a). Among other outcomes, this has led to the establishment of a public Forum against Disinformation Campaigns in the Field of National Security (Foro contra las campañas de desinformación en el ámbito de la Seguridad Nacional) as a consultative body to advance a whole-of-society approach, relevant working groups and publications. Launched in 2022, this forum has brought together more than 100 experts from academia, think tanks, journalism, digital companies and NGOs. Every year the DSN publishes a report on the initiatives developed under the forum.

[The forum as a] space for collaboration between public institutions and civil society, the private sector and academia has cemented its position as a trustworthy tool that contributes to generation and sharing of knowledge on the risk disinformation poses to our democracy and the rule of law, as well as encouraging debate on the available mechanisms to address those threats. It brings together representatives from the main sectors in society involved in detecting, understanding and mitigating threats.

—Loreto Gutiérrez Hurtado, Director of the DNS and Chair of the Forum against Disinformation Campaigns in the Field of National Security (Government of Spain 2025b: Introduction).

Questions to consider regarding mandate:

- What specific gaps in current institutional approaches could this institution address, especially regarding coordination and information sharing between government and non-government stakeholders?

- How would the institution ensure legitimacy and trust among diverse stakeholder groups (especially in contested domains)?

- What principles would guide its engagement with stakeholders, considering the existing tensions between transparency, security and pluralism, as well as its recommendations regarding politically contested areas?

- How should the institution balance responsiveness to emerging threats with the need for sustainable, long-term societal development?

- What boundaries must be respected to avoid duplication or jurisdictional conflict?

3.3. Roles and responsibilities

This section briefly outlines and discusses the key functions a national institution tasked with organizing and coordinating stakeholders’ activities could perform. It is based on analyses of lessons learned from different democratic countries already engaged in whole-of-society and whole-of-government approaches. While it should not act as the only port of call, structuring these core responsibilities under one national institution may also increase opportunities for international coordination.

- Focal point. The institution could marshal resources and organize a whole-of-government and whole-of-society approach to raising resilience and ensuring the integrity of the national information ecosystem, in line with democratic values and principles. Subject to mandate, structure and position in the national governance system, the institution’s responsibilities may span leading, developing, facilitating and, where necessary, coordinating activities. One example of such coordination could be around national election cycles. If positioned as a bridge between government and non-government interests and siloed mandates, the public institution could act as a trusted coordinator that identifies gaps and initiates interagency or multistakeholder collaboration, which could also lead to international cooperation.6 As a national champion of the information ecosystem, this organization’s role would be limited to identifying systemic gaps, developing concepts and recommendations, capacity building and streamlining flows of information, leaving the formulation and delivery of operational responses to relevant agencies (e.g. ministry of foreign affairs, defence or interior).

- Stakeholder engagement. Due to numerous socio-political risks and sensitivities, as well as evolving hybrid threats, it would be critical for the institution to engage with relevant domestic stakeholders and foreign partners through collaborative partnerships. Domestically, this could take the form of a national advisory council affiliated with the new institution, comprising experts from government, civil society and academic communities. They would convene to assess vulnerabilities in the domestic ecosystem and develop non-binding, public recommendations for addressing them.7 Some of the responsibilities mentioned below could also be operationalized through long-term funded programmes involving civil society and academic partners (e.g. capacity building, monitoring or research). Internationally, this could involve close partnerships with similar national institutions to advance a coherent, whole-of-democracy approach to the global information environment, in line with democratic values and principles.

- Information ecosystem monitoring and analysis. As an independent national organization, it would be imperative for this institution to develop and support assessments and analyses that generate transparent evidence. Identifying factors and conditions that influence changes in the national information ecosystem, including threats and trends, would help all stakeholders rally against harmful activities. These assessments could happen at two levels. First, strategic assessments could focus on longitudinal analyses of socio-political, legal, economic, cultural, regulatory, security and other factors and trends that affect the entire ecosystem. Going beyond social and traditional media analyses, these studies would generate evidence in support of systemic regulatory, legal and policy decision making, as well as infrastructure development and resourcing to close gaps. Second, more operational assessments could focus on evolving information threats, in partnership with trusted civil society partners and government agencies. Currently, most of this monitoring takes place through established government mechanisms; some of this may continue, due to national security or reputation management imperatives. Nevertheless, improving collaboration and information sharing across expert stakeholder communities would elevate transparency and trust in threat reports, thereby enhancing public awareness and resilience during electoral cycles and beyond.8 By fostering information-sharing protocols between domestic intelligence agencies, electoral commissions, media and independent civil society organizations, the institution would support the development of a more comprehensive threat assessment picture and improve trust in democratic processes and governance overall.

- Knowledge and capacity building. By developing partnerships with academic, think tank, media and civil society organizations, the institution could act as a national clearing house for knowledge and awareness generation, improving societal understanding of critical factors influencing the information ecosystem, its trends and gaps, as well as possible solutions. By supporting these partnerships through dedicated, long-term funding for policy-oriented research, development of technical tools and learning modules, the institution could foster alignment and consistent delivery of skills, capacities and knowledge across the society and government. Building on this knowledge, the institution could then coordinate standardized development and delivery of curricula and training to different stakeholder communities, in partnership with civil society actors.

- Communication. As an independent public entity that fosters critical relationships, as described above, this institution would be well positioned to actively shape public dialogue on the challenges, gaps and futures of the modern information society. This depends, of course, on whether the right political conditions are present and it manages to acquire widespread trust from members of society. If so, it could mitigate the challenges facing government strategic communication efforts, especially in a risk-averse public service. In a very dynamic and events-rich information space, every information void becomes an opportunity for disinformation or manipulation. Reports and recommendations resulting from the institution’s various activities, produced in a transparent and accessible manner, using evidence and facts, could foster new norms, inform policy and forge partnerships.

Box 3.3. France’s VIGINUM

Founded in 2021 by a presidential (executive) decree to protect democracy and electoral debate, VIGINUM (Service de vigilance et protection contre les ingérences numériques étrangères) is an operational and technical service whose mission is to detect and characterize foreign digital interference targeting France’s national interests. Working only in open-source intelligence, VIGINUM analyses information manipulation sets; identifies and follows tactics, techniques and procedures deployed by foreign actors; and raises awareness about the threat among young people, the general public, the media and government agencies (VIGINUM n.d.; see also Government of France 2021).

Its position within the Secretariat-General for Defence and National Security (Secrétariat général de la défense et de la sécurité nationale) under the French prime minister, allows the service to coordinate the respective efforts of the Ministries for Europe and Foreign Affairs, Armed Forces and the Interior. Operating exclusively as an investigative service, it does not correct inaccurate information. The service follows strict rules regarding open-source data collection and retention to ensure compliance with privacy and ethics laws and avoid perceived surveillance of citizens. Since 2024, the service has collaborated with France’s Digital Communication Regulatory Authority (Autorité de régulation de la communication audiovisuelle et numérique, Arcom) by providing technical support for the implementation of the EU Digital Services Act.

VIGINUM’s proactive monitoring focuses on behavioural indicators related to adversarial networks and infrastructure, which improves its ability to identify emerging threats and provide early warnings to the wider system. Improving capacity and awareness across relevant stakeholder communities and enhancing technical interoperability with international partners to foster coordinated responses are key focus areas.

There is a need to facilitate the emergence of a cohesive European and international culture in the fight against information manipulation. It should be focused on three objectives—standardizing detection practices, strengthening detection capacities in targeted countries and fostering interoperability between states and with all the community involved in the fight against information manipulation. Finally, there should be better coordination of the public and private sectors and civil society to guarantee the coherence of our response and strengthen society’s resilience.

—Marc-Antoine Brillant, Head of Department, VIGINUM

Questions to consider regarding roles and responsibilities:

- What core functions should the institution perform to serve as a national point of authority on information ecosystem issues, including resilience?

- What role could the institution play in effectively representing and mediating between emerging domestic priorities and approaches (outside of official policy) and international partners in government and non-government sectors, especially in emerging areas of shared concern?

- What role should the institution play in conducting or commissioning recurrent analyses of the national information ecosystem?

- What conditions and expectations could be imposed on participating stakeholders to promote shared outcomes, implement adopted recommendations or resolve disputes?

3.4. Organizational structure

Traditionally, organizational structure is understood through the policies, roles and responsibilities, governance models, and intra- and interorganizational relationships that define an institution’s function. To some extent, this discussion paper has already touched on a few of these aspects. Since different national contexts, policy aspirations and practical constraints will impact how these would be structured in each case, we take a more systemic, whole-of-society view on this issue.

Developing new governing mechanisms that connect various actors, processes and resources in support of relevant information flows and decision making requires a strong political will and commitment. In essence, by calling for a threat-agnostic, whole ecosystem perspective to building resilience and countering systemic information threats, political leaders can foster the creation of networks with shared awareness and process-driven collaboration, ultimately advancing numerous national goals.

One of the key challenges on this path is developing processes and relationships that can be stable and flexible at the same time. On the one hand, flexibility is important for governance systems to deal with unpredictable, non-linear forms of socio-political and geopolitical change. On the other hand, this institution would be required to navigate existing initiatives and advance new methods, all while ensuring that they take root sufficiently to produce the desired effects. To achieve this, its work must be based on high professionalism in policy and technical matters, transparent organizational behaviour, respect for fundamental rights and ethical standards and recognized leadership, among other characteristics. Similarly, due to many sensitivities (e.g. national security and defence) and potential for national impact, the institution must combine access to executive and legislative branches with the ability to engage across other stakeholder communities. These and related principles, alongside an honest broker reputation, would be fundamental for fostering interorganizational and intersectoral trust and buy-in. In turn, these would provide a solid foundation for establishing shared norms and practices.

In practice, the organizational structure would depend on its mandate and the roles it has been asked to perform, triggering an analysis of what skills, levels of seniority and prior experience would be required among its staff. As part of a mission-oriented organization, all functional teams would need to possess a high degree of shared horizontal awareness, while also focusing on delivering specific results. This would require a robust internal communications and project management platform. If pursuing a whole-of-society engagement becomes one of the institutional objectives, adopting a distributed network approach to organize the delivery of its functions could, in principle, keep the core structure leaner and more transparent. As discussed earlier, this approach should facilitate greater trust and buy-in across all stakeholder communities.

As a first step, a detailed mapping and analysis of existing national efforts (and their results), needs, opportunities and gaps would identify relevant stakeholders with proven records and facilitate the development of work plans. From here, it would be straightforward to devise appropriate methods for engaging partners in implementing activities, whether by funding open-source monitoring or facilitating working groups. Of course, given the many challenges involved, setting up and running this organization and its networks would not be easy. Flexibility and experimentation would remain key characteristics—and perhaps requirements—for both its staff and processes. The development of these deliberative, whole-of-society processes, just like the institution itself, would involve continuous effort to boost collective understanding of how resilient domestic ecosystems evolve in line with democratic values and aspirations.

Questions to consider regarding organizational structure:

- What structural model best supports agility, inclusivity and credibility (e.g. permanent secretariat, rotating panels, thematic working groups)?

- How would the leadership be appointed and the public funding secured in a way that guarantees independence from the executive branch or political influence?

- What internal capabilities (e.g. analytical, legal, technical) would be essential for fulfilling its mandate?

- How should the decision-making and recommendation processes be organized and documented to ensure transparency, accountability and efficiency?

Box 3.4. Moldova’s Centre for Strategic Communications and Countering Disinformation

Facing the continuous onslaught of Russian hybrid operations, including information attacks (EUvsDisinfo 2025), Moldova inaugurated its Centre for Strategic Communications and Countering Disinformation in 2023. Established by a parliamentary decree, one of the centre’s key tasks is to consolidate and improve coordination across government agencies responsible for specific aspects of the fight against information manipulation and foreign interference (e.g. the Audiovisual Council, the Security and Information Service, the Coordinating Council on Ensuring Information Security and the National Cybersecurity Agency).

One of its first outputs was the ‘Concept of Strategic Communication and Countering Disinformation, Information Manipulation, and Foreign Interference for the Years 2024–2028’. By aligning with objectives in the National Security Strategy, the concept identified various forms of information manipulation and interference as threats and risks to national interests, acknowledged governance vulnerabilities and proposed specific actions to ensure national security and resilience, in line with democratic principles (Parliament of the Republic of Moldova 2023). Since its establishment, the centre has continued to test and implement different practices, working in tandem with government agencies, civil society and industry.

Recognizing numerous systemic vulnerabilities, the centre’s approach focuses on raising human resilience by improving societal consensus regarding how information threats impact lives, values and national security. A proactive and preventative approach to resilience also requires regular threat and vulnerability assessments, analysis of popular attitudes and related gaps and elevated trust in democratic institutions, values and practices. At the same time, political leaders and decision makers must acknowledge that building a whole-of-society approach to resilience is a long-term process. In addition to government communications, these actors must engage with critical voices in authentic debates beyond electoral cycles to bridge perception gaps and build trust.

Political levels in democratic societies must recognize that information threats must be addressed as part of a national security approach. This opens paths to developing and organizing proactive efforts between all national stakeholders, and in collaboration with international partners, in pursuit of shared national interests.

—Ana Revenco, Director, Centre for Strategic Communication and Countering Disinformation, Republic of Moldova

3.5. Oversight

Due to various socio-political, security and effectiveness concerns and expectations, a national institution working on information-related issues would require strong public oversight. Ensuring that this institution operates in a transparent and accountable manner would also diminish possible risks associated with perception of government control, threats to fundamental human rights or political bias. In this regard, a multistakeholder governance board comprised of representatives from civil society, academic, industry and government sectors could govern this institution’s activities, advise management and present detailed annual reports. While details would vary depending on context, board members could be selected based on their professional acumen and public service record, with their tenure staggered to ensure continuity and rejuvenation. The nomination and selection processes should be organized and run in a completely transparent manner and on record.

The annual reports from the governance board could be presented in a legislative body for public scrutiny. To ensure this institution operates under the strict rule of law, these reports should cover the nature and scope of conducted activities, relevant statistics, information about staff appointments and other miscellaneous matters, such as complaints and remedy mechanisms. Aside from building societal trust for its activities and purpose, such levels of transparency and accountability would also proactively mitigate possible negative perceptions. Regular engagement with and participation of traditional and new media in its activities could serve, when the context allows, as additional opportunities to inform the public of the institution’s activities.

On the more administrative side, the internal operations of the institution could be governed by existing policies and acts, as applied to other similar government organizations.

Questions to consider regarding oversight:

- What mechanisms would ensure this institution operates in a transparent and publicly accountable manner to guarantee its legitimacy?

- Who should be responsible for evaluating the institution’s performance and impact?

- How would the oversight be structured to avoid politicization or capture by narrow interests?

- What role should parliament, independent bodies or civil society play in oversight?

- How would feedback loops be built into the institution’s operations for continuous improvement?

3.6. International coordination