Assessing a Decade of Action

SDG 5 and SDG 16 in Focus

This paper examines a decade of global progress on Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) 5 (Gender Equality) and 16 (Peace, Justice and Strong Institutions) since the adoption of the 2030 Agenda in 2015, using data from International IDEA’s Global State of Democracy Indices. Despite some gains—such as a modest 2 per cent increase in global Gender Equality scores and higher women’s parliamentary representation— SDG 16 is largely backsliding.

All four core democratic pillars under SDG 16—Representation, Rights, Rule of Law and Participation—have declined globally since 2015, with the largest percentage declines in Representation and Participation and the greatest number of countries experiencing significant declines in Representation and Rule of Law. Five of the six SDG 16 targets assessed show declines, with the steepest percentage drops in effective, accountable institutions (SDG 16.6), representative decision making (SDG 16.7) and access to information and fundamental freedoms (SDG 16.10), and the largest number of countries declining on SDG 16.3 in rule of law. Only SDG 16.5, on reducing corruption, shows slight improvement.

The analysis underscores how democratic backsliding and shrinking civic space often lead to setbacks in gender equality—evident in declining women’s participation in civil society, freedom of expression and access to justice. Yet, progress stories from countries like Costa Rica, Egypt and Moldova show that legal reforms, gender quotas and political will can still drive change.

The paper emphasizes the need for urgent, renewed global commitment to prioritize democratic resilience and gender equality in development efforts—by protecting civic space, investing in women’s rights and democratic institutions, and fostering inclusive, cross-sector collaboration to uphold the 2030 Agenda’s promise.

Ten years into the implementation of the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development, progress on Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) 5 (Gender Equality) and 16 (Peace, Justice and Strong Institutions) is faltering. These two goals are not only essential in their own right; they are also foundational enablers for the entire 2030 Agenda. Advancing gender equality and building effective, accountable institutions are prerequisites for achieving inclusive, peaceful and sustainable development across all sectors. Conversely, stagnation or regression in these areas risks undermining progress across the full spectrum of global goals.

This paper draws on data from International IDEA’s Global State of Democracy Indices to assess progress and setbacks on key indicators related to SDG 5 and SDG 16 over the past decade. The findings reveal a troubling picture: backsliding is evident across 5 of the 6 SDG 16 targets measured by the International IDEA and across all four dimensions of democracy—Representation, Rights, Rule of Law and Participation (see Box I.1). In many regions, progress has stalled or reversed, often driven by democratic erosion and rising authoritarianism. Only 3 of the 29 indicators produced by International IDEA—Gender Equality, Absence of Corruption and Basic Welfare—have shown modest global progress since 2015, but even these gains have been slow and insufficient. Notably, Gender Equality (SDG 5) has declined in Asia and the Pacific, North America and Southern Africa, highlighting a pattern of backsliding in many regions of the world.

This backsliding is occurring at a moment of acute vulnerability for both democracy and sustainable development. Cuts to foreign assistance, particularly in the areas of democracy, governance and rights, are likely to exacerbate these current setbacks—disproportionately affecting the very actors and institutions that work to uphold the principles enshrined in SDGs 5 and 16 (Global Democracy Coalition 2025). Without targeted support and renewed political will, the international community risks falling even further behind on the 2030 Agenda.

This paper argues that restoring momentum on SDGs 5 and 16 must be a top priority for governments, donors and multilateral institutions. Progress in these areas is not optional; it is a prerequisite for achieving the 2030 Agenda as a whole. The next few years will be critical in determining if the promise of the 2030 Agenda can be realized at all.

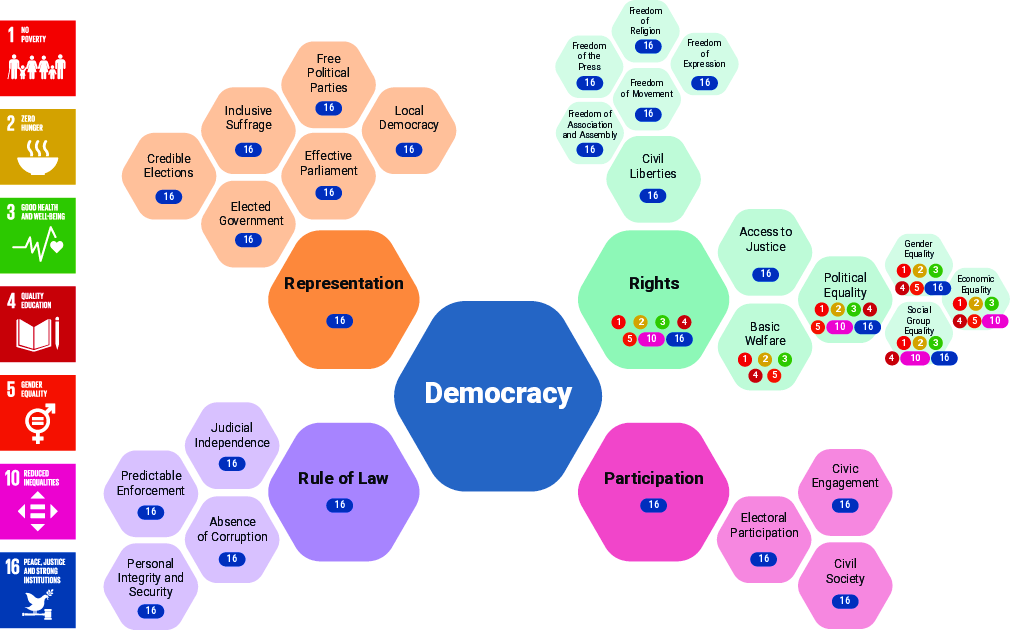

Box I.1. Global State of Democracy Indices and SDGs 5 and 16

International IDEA’s Global State of Democracy (GSoD) Indices assess democratic performance across four core dimensions—Representation, Rights, Rule of Law and Participation—based on 29 indices aggregated from 154 source indicators. The GSoD Indices cover 174 countries from 1975 through 2024 and score each dimension from 0 to 1, with three tiers of democratic performance, depending on the score—low (0.0–0.4), mid-range (0.4–0.7) or high (0.7–1.0). For the period included in this analysis (2015–2024), data sets are available for 173 countries.

The GSoD Indices help monitor progress on 7 SDGs (Figure I.1)—SDG 1 (No Poverty), SDG 2 (Zero Hunger), SDG 3 (Good Health and Well-Being), SDG 4 (Quality Education), SDG 5 (Gender Equality), SDG 10 (Reduced Inequalities) and SDG 16 (Peace, Justice and Strong Institutions)—and 6 of the 12 targets of SDG 16 (16.1, 16.3, 16.5, 16.6, 16.7 and 16.10). The GSoD Indices complement official United Nations statistics with democracy-specific data, offering additional insights into institutional and rights-based dimensions of sustainable development.

SDG 5 (Gender Equality)

Gender equality, a core pillar of democracy, is measured under the Political Equality subcomponent of the Rights dimension. The GSoD Gender Equality score draws on nine indicators from five leading global sources—including the Varieties of Democracy Institute (V-Dem Institute), the Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation, the World Bank, the International Labour Organization and the World Economic Forum’s Global Gender Gap Report—capturing both expert-coded and observational data on women’s political participation and representation in legislatures and in civil society, power distributed by gender and women’s political empowerment and exclusion, labour force participation, access to managerial positions, educational attainment and control over financial accounts.

SDG 16 (Peace, Justice and Strong Institutions)

The GSoD Indices provide data for 6 of the 12 SDG 16 targets, across all four GSoD dimensions:

- Rights—civil liberties, including freedoms of expression, assembly, religion and movement;

- Representation—credible elections, inclusive suffrage, political pluralism, elected institutions and local democracy;

- Rule of Law—judicial independence, absence of corruption, legal predictability and public integrity; and

- Participation—strength of civil society and civic engagement.

Data for the SDG 5 and SDG 16 indicators in this paper is not based on member state reporting, but on a mix of expert-coded data (e.g. V-Dem data sets) and institutional assessments (e.g. by Freedom House or the World Bank). This multidimensional approach offers a globally comparable picture of democracy’s contribution to sustainable development, highlighting its role as an enabler of inclusive, peaceful and resilient societies.

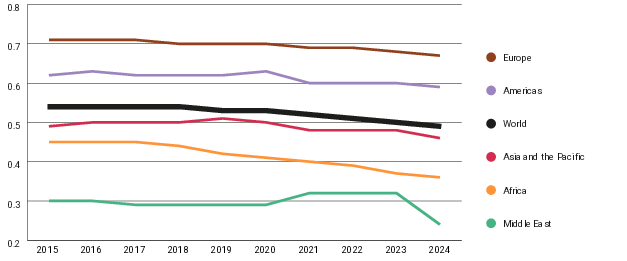

1.1. SDG 16

All four key GSoD categories—Representation, Rights, Rule of Law and Participation—for SDG 16 have declined globally since 2015 (Tables 1.1 and 1.2). This downward trend spans all regions except Asia and the Pacific, where Rule of Law has stagnated rather than declined. The sharpest drops are in Representation, especially in Credible Elections, Elected Government and Effective Parliament. Global declines have also been observed in Electoral Participation and Freedom of Expression.

| GSoD indicator | % change globally | Number of countries declining | Number of countries advancing |

|---|---|---|---|

| Representation | –7.39 | 33 | 9 |

| Rights | –3.44 | 13 | 6 |

| Rule of Law | –3.16 | 39 | 17 |

| Participation | –4.19 | 10 | 3 |

The GSoD Indices and their conceptual framework (International IDEA 2023) provide data on 6 of the 12 targets of SDG 16 (16.1, 16.3, 16.5, 16.6, 16.7 and 16.10) (Table 1.2). The data shows declines across five targets. The largest declines observed since 2015 are for SDG 16.6, on effective, accountable and transparent institutions, SDG 16.7 on representative decision making, and for SDG 16.10, on ensuring access to information and protecting fundamental freedoms (Table 1.2). The only target analysed by International IDEA that experienced some improvement is SDG 16.5 on reducing corruption. However, of the 31 countries that improved, over a third still face high levels of corruption—dropping from very high to high—and none achieved low levels.

| SDG 16 target | Theme of target | Related GSoD category | Related GSoD factors and subfactors | % change since 2015 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SDG 16.1 | Reducing violence | Rule of Law | Personal Integrity and Security | –2.24 |

| SDG 16.3 | Promotion of the rule of law and access to justice | Rights; Rule of Law | Access to Justice; Judicial Independence; Predictable Enforcement | –3.07 |

| SDG 16.5 | Reducing corruption | Rule of Law | Absence of Corruption | +1.53 |

| SDG 16.6 | Effective institutions | Representation; Rule of Law; Participation | Free Political Parties; Elected Government; Effective Parliament; Local Democracy; Judicial Independence; Predictable Enforcement; Civil Society; Civic Engagement | –4.97 |

| SDG 16.7 | Representative decision making | Representation; Rights; Rule of Law; Participation | Credible Elections; Inclusive Suffrage; Free Political Parties; Elected Government; Effective Parliament; Local Democracy; Access to Justice; Political Equality; Judicial Independence; Civil Society; Civic Engagement; Electoral Participation; Social Group Equality; Gender Equality | –4.47 |

| SDG 16.10 | Access to information and fundamental freedoms | Rights; Rule of Law | Civil Liberties; Predictable Enforcement; Personal Integrity and Security; Freedom of Expression; Freedom of Association and Assembly; Freedom of Religion; Freedom of Movement; Freedom of the Press | –4.32 |

The large declines in Representation follow a pattern of democratic decline observed globally over the past decade (International IDEA 2024). The decline in Representation can be explained by a number of factors. For example, the past decade has seen a surge in coups, with 27 successful coups between 2015 and 2024—a 42 per cent increase compared with the previous decade (Peyton et al. 2025). There has also been a decline in the quality of elections. International IDEA data shows an increase in the number of disputed elections since 2020, resulting in a range of responses, from boycotts to legal challenges, election-related protests or the losing candidate’s refusal to recognize the election results. One in five elections since 2020 have been disputed in some way (International IDEA 2024). Electoral contestation was prevalent during the 2024 super cycle, with 40 per cent of countries holding elections that year experiencing some form of dispute—highlighting growing tensions around electoral integrity worldwide (International IDEA n.d.d).

Twenty-six per cent of the elections held in 2024 were followed by protests, with 18 per cent of them experiencing violence resulting in civilian deaths. Additionally, 15 per cent saw the losing party reject the election results, while 12 per cent saw opposition boycotts (International IDEA n.d.d).

Regional trends

Despite the Middle East experiencing the lowest scores in electoral quality among the regions, the largest declines since 2015 have been observed in Africa, related in large part to the region’s autocratization (Figure 1.1). Two thirds of the coups in the world since 2015 have taken place in African countries. The military is in power in eight countries in the region (Childs Daly 2024). Fifty per cent of the countries across the region are not free or have no or low levels of electoral integrity (Freedom House n.d.; International IDEA n.d.d).

Another key sign of electoral decline is decreasing voter turnout, the indicator with the third-sharpest decline since 2015 (Figure 1.2). The steepest drops have also taken place in Africa, where conflict and militarization have surged over the past decade. Election-related unrest and violence have contributed to dampen voter turnout (van Baalen 2023).

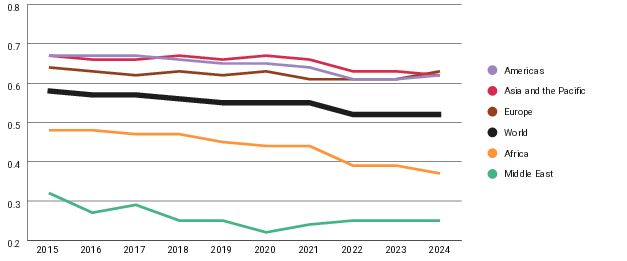

1.2. SDG 5

Despite concerning declines across most indicators, 3 of the 29 GSoD Indices—Basic Welfare (Social Rights), Absence of Corruption (SDG 16.5) and Gender Equality (SDG 5)—have seen some improvements since 2015 (Table 1.3).

| GSoD indicator | % increase | Number of countries statistically declining | Number of countries statistically advancing |

|---|---|---|---|

| Basic Welfare | 2.83 | 1* | 6 |

| Gender Equality1 | 2.27 | 2** | 10 |

| Absence of Corruption | 1.53 | 19 | 28 |

However, progress on SDG 5 still falls short: global Gender Equality scores have risen by just a little over 2 per cent—only half the pace of the previous decade. Some progress has been seen in Europe (+4.13 per cent), the Middle East (+3.8 per cent), Latin America and the Caribbean (+4.35 per cent) and Africa (+0.91 per cent). Asia has driven the global decline, however, with a regional drop of 0.6 per cent, led by a steep 6.22 per cent fall in South Asia and further declines in Central Asia

| Region and subregion | % change |

|---|---|

| Asia and the Pacific | –0.60 |

| South Asia | –6.22 |

| Central Asia | –2.37 |

| East Asia | –0.72 |

| Africa | +0.91 |

| Southern Africa | –2.57 |

| Europe | +4.13 |

| Latin America and the Caribbean | +4.35 |

| North America | –5.31 |

The political and public life dimensions of the GSoD Indices’ Gender Equality score include measures of women’s parliamentary representation and their participation in civil society. While not captured by the GSoD subfactor on Gender Equality, access to justice and freedom of discussion also affect women differently than men (UN General Assembly 2021). Generally, the democratic backsliding reflected in the deterioration of SDG 16 indicators described in the prior section tends to disproportionately affect women, who, due to pre-existing structural vulnerabilities, often experience heightened levels of political exclusion and targeted repression compared to men. The following sections provide an analysis of how key political dimensions of gender equality have evolved since 2015.

Women in parliament

Women’s parliamentary representation is the only indicator that has seen gains across all regions since 2015, with the exception of the Middle East, where it has decreased by almost 5 per cent (Table 1.5). Despite these gains, only slightly over a quarter of the world’s legislators are women, which is far from parity (IPU n.d.a). At the current rate, it is estimated that it will take another 40 years to achieve parity (Silva-Leander 2025). Asia and the Pacific saw the largest gains in women’s parliamentary representation since 2015, though the region still ranks second-lowest globally (IPU 2015). The Americas lead globally, with women holding 35.4 per cent of parliamentary seats (IPU n.d.a).

Women’s participation in civil society

While women’s participation in parliaments has increased globally since 2015, women are facing increasing restrictions on their involvement in civil society. These restrictions often occur in contexts of shrinking of civic space, in which women activists and their organizations tend to be particularly targeted (CIVICUS 2024). The sharpest decline has occurred in Asia and the Pacific

| Region | 2015 | 2024 | % change |

|---|---|---|---|

| World | 1.37 | 1.34 | –2.19 |

| Americas | 1.60 | 1.63 | +1.88 |

| Europe | 2.07 | 2.01 | –2.90 |

| Africa | 1.19 | 1.20 | +0.84 |

| Asia and the Pacific | 1.10 | 0.99 | –10.00 |

| Middle East | 0.55 | 0.55 | 0.00 |

In Asia, the sharp decline in women’s civil society participation has largely been driven by a growing authoritarian pushback against feminist activism and shrinking civic space.

In Afghanistan, for example, women’s organizations have been banned since the Taliban’s return to power in 2021, and women are prohibited from public assembly and participation in non-governmental organizations (NGOs) (AP News 2024). In Myanmar, since the 2021 military coup, women’s rights activists and organizations have faced arrests, surveillance and forced shutdowns (Human Rights Watch 2022).

In Europe, despite generally high levels of Gender Equality, declines in this indicator are largely attributed to democratic backsliding and a societal backlash against gender-focused civil society efforts.

In Hungary and Poland, governments took explicit measures prior to 2024 to defund or discredit women’s rights organizations, especially those advocating for reproductive rights and gender equality. Rising anti-gender movements across Europe have pushed for laws and narratives that delegitimize feminist civil society organizations and restrict their public funding and engagement (Council of Europe 2025).

Women’s freedom of discussion

Women’s freedom of discussion has decreased by 25 per cent since 2015 across all regions except the Middle East, where levels were lowl to start with (Table 1.7). This global decline has been driven by a combination of rising authoritarianism, online and offline gender-based harassment, shrinking civic space and increased censorship targeting feminist voices, especially in contexts where women’s rights are framed as politically threatening or culturally subversive.

| Region | 2015 scores | 2024 scores | % change |

|---|---|---|---|

| World | 0.95 | 0.71 | –25.26 |

| Americas | 0.53 | 0.15 | –71.70 |

| Europe | 2.12 | 1.74 | –17.92 |

| Africa | 0.57 | 0.50 | –12.28 |

| Asia and the Pacific | 0.57 | 0.30 | –47.37 |

| Middle East | –0.43 | –0.47 | +9.30 |

Gender-based violence

As global conflicts rise, women are hit hardest: conflict-related sexual violence has surged by 50 per cent since 2022, with women and girls accounting for 95 per cent of victims (UN Women 2025a).

Violence affects women across all contexts. International IDEA’s report on the 2024 super-cycle year of elections identifies violence against women in elections as a particularly significant and widespread challenge, with gender-based violence occurring in 28 out of 54 elections in 2024 (Asplund et al. 2025). The report identifies violence in response to a backlash against women’s growing presence in political life.

Despite the concerning trends, UN Women (2025a) reports that, since 2019, 90 per cent of countries have reported introducing or strengthening laws on violence against women and girls, while 79 per cent have established, updated or expanded national action plans to end violence. While some countries are devising new means to stop technology-facilitated violence—75 countries now have protections against sexual harassment online—more such measures are needed (UN Women 2025a).

Women’s access to justice

Women’s access to justice has declined across all regions, with the largest decline in the Americas (Table 1.8), where impunity and institutional bias collectively explain why women’s access to justice has declined across the region. In countries like Mexico, it is estimated that around 10 women and girls are killed every day by intimate partners or other family members, and only 2 per cent of cases end in a criminal sentence (Minard and Carmo 2024). Studies have shown that domestic violence cases are significantly more likely to result in convictions when overseen by female judges, highlighting how gender bias within the judiciary can be a major barrier to justice for women (Laneuville and Possebom 2024).

| Region | 2015 scores | 2024 scores | % change |

|---|---|---|---|

| World | 0.88 | 0.77 | –12.50 |

| Americas | 0.71 | 0.49 | –30.99 |

| Europe | 2.17 | 1.97 | –9.22 |

| Africa | 0.41 | 0.40 | –2.44 |

| Asia and the Pacific | 0.68 | 0.58 | –14.71 |

| Middle East | 0.29 | 0.23 | –20.69 |

2.1. Advances

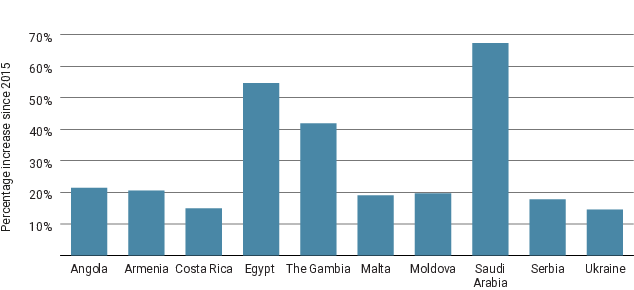

According to International IDEA’s GSoD Indices, despite several countries and regions improving their Gender Equality scores, only 10 countries have experienced statistically significant positive gains since 2015—Angola, Armenia, Costa Rica, Egypt, The Gambia, Malta, Moldova, Saudi Arabia, Serbia and Ukraine (Figure 2.1 and Table 2.1).

| Country | 2015 scores | 2024 scores | % change |

|---|---|---|---|

| Angola | 0.48 | 0.59 | +21.46 |

| Armenia | 0.51 | 0.62 | +20.56 |

| Costa Rica | 0.75 | 0.86 | +14.95 |

| Egypt | 0.29 | 0.45 | +54.65 |

| The Gambia | 0.41 | 0.58 | +41.86 |

| Malta | 0.65 | 0.78 | +19.06 |

| Moldova | 0.68 | 0.82 | +19.67 |

| Saudi Arabia | 0.16 | 0.26 | +67.40 |

| Serbia | 0.61 | 0.71 | +17.81 |

| Ukraine | 0.66 | 0.76 | +14.51 |

Several factors have contributed to the increase in Gender Equality scores in these countries, including the implementation of gender quotas, or the introduction of constitutional reforms and the adoption of new laws. In Costa Rica, for example, women’s representation in parliament increased from 33 per cent in 2015 to 49 per cent in 2025 (International IDEA n.d.a). In 2020 Costa Rica became the first country in Central America and the 28th UN member state to legalize same-sex marriage (Haynes 2020), opening the door for greater equality in the region.

In Egypt, advancements in gender equality have been driven by constitutional and legal reforms aimed at combating violence and discrimination against women (International IDEA n.d.c). Increased political representation through the implementation of quotas has also played a role in advancing Egypt’s score in Gender Equality (UN Women Egypt n.d.), with women’s representation in parliament increasing from 15 per cent in 2016 to nearly 28 per cent in 2024 (IPU n.d.b). Despite these advances, however, women’s influence remains limited, with many facing marginalization in party structures and lacking access to leadership roles (Yefet and Friedberg 2024).

Gender quotas were also established in Moldova in 2016, mandating that at least 40 per cent of candidates on party lists and in decision-making positions must be women (UN Women Europe and Central Asia 2016). By 2024, the number of women in Moldova’s Parliament had reached 41 per cent from 22 per cent in 2015 (World Bank n.d.). Moreover, Moldova ratified the Istanbul Convention in 2021, which came into force in May 2022, strengthening protections against gender-based violence (Council of Europe 2022). Despite these advances, women in Moldova face significant challenges in both education and the labour market due to persistent patriarchal norms, which limit women’s educational and career choices and contribute to wage disparities, occupational segregation and unequal family responsibilities (UN Women Europe and Central Asia n.d.a).

Serbia ranks 44th in Gender Equality in International IDEA’s GSoD Indices, with a score of 0.71 in 2024, moving to high-range levels from 2015 (Table 2.1). In 2021 Serbia enacted a modernized gender equality law and strategy, creating a comprehensive normative framework for gender action plans, gender risk assessments and the full integration of gender issues in public policies (UN Women Europe and Central Asia n.d.b). However, the Constitutional Court suspended the law in 2024 after initiating proceedings to evaluate its constitutionality, putting at risk hard-won progress (Mordt and Rikanovic 2025).

The Gambia established a Ministry of Gender, Children and Social Welfare in 2019, taking a further step towards enhancing coordination and supporting national initiatives on gender equality and women’s empowerment. The ministry developed a revised Gender Policy for 2025–2034 to strengthen capacity building and resource allocation for achieving gender equality in the country (Republic of The Gambia 2024). The Gambia also enacted the Women’s Amendment Act (2015), banning female genital mutilation (FGM) and safeguarding the rights of women and girls from this physically, psychologically and socially harmful practice. However, the recent attempt by parliament to overturn the FGM ban has shown how fragile the protection of gender rights still is in the country (Christensen 2024), highlighting the crucial role of civil society actors in holding leaders accountable and underscoring the importance of providing more meaningful space for women in politics. Currently, only 8.6 per cent of members of parliament in The Gambia are women (IPU n.d.b).

Despite the ongoing war, Ukraine maintained momentum in improving its Gender Equality score, achieving a 14.5 per cent increase from 2015 (Table 2.1). However, the war has also severely impacted women, who now face increased gender-based violence—up 36 per cent since 2022—alongside higher unemployment, reduced decision-making power and a worsening mental health crisis (UN Women 2025b). According to UN Women, only 48 per cent of displaced women are employed, compared with 71 per cent of men, and the gender pay gap stands at 41 per cent.

While legislative and institutional reforms have contributed to measurable progress in countries that had seen advances in their gender equality metrics since 2015, structural challenges—including weak enforcement, persistent gender norms, political tokenism and crisis-related setbacks—continue to hinder meaningful and sustained equality in some contexts.

2.2. Declines

Since 2015 only two countries—Afghanistan and Madagascar—have shown statistically significant declines in their Gender Equality scores, according to International IDEA’s GSoD Indices (Table 2.2).

| Country | 2015 scores | 2024 scores | % change |

|---|---|---|---|

| Afghanistan | 0.27 | 0.07 | –73.5% |

| Madagascar | 0.60 | 0.48 | –21.0% |

Afghanistan recorded the steepest decline

Madagascar’s Gender Equality score has decreased by 21 per cent since 2015 (Table 2.2). The deterioration is linked to a number of factors. Deep-rooted gender norms, violence and early marriage limit girls’ education and women’s economic opportunities, reinforcing disparities in pay, employment and agency for women in Madagascar (World Bank 2023). Women are paid 37 per cent less than men and are 20 per cent more likely to be unemployed, which reinforces the Malagasy social norm whereby men have a greater right to employment than women—an assertion believed by 66 per cent of the respondents in an Afrobarometer study (Tianjoky 2024). This discrepancy in women’s role in society is also seen in politics, with women’s parliamentary representation declining from 20 per cent in 2015 to only 14 per cent in 2025, dropping to 147th ranking in the world (out of 181 countries) (IPU n.d.b). Explanatory factors may include the lack of gender quotas in the Malagasy mixed electoral system and the increasing registration fees for electoral candidates since 2015, which poses an additional obstacle for women participating in elections (Gender Links 2020).

Setbacks in gender equality, driven by political, legal and structural challenges, affect many countries and regions around the world. The cases of Afghanistan and Madagascar underscore how political instability, authoritarianism, shrinking civic space and a lack of legal safeguards and investment in women can significantly reverse gains in gender equality.

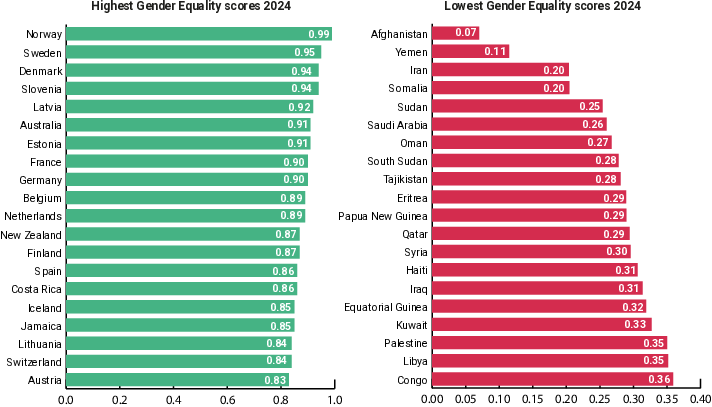

According to an analysis of 173 countries by International IDEA, 26 countries scored in the low range for Gender Equality in 2024, including Afghanistan (0.07), Iran (0.20), Qatar (0.29), Haiti (0.30), Chad (0.36), the Solomon Islands (0.36) and Türkiye (0.38). A total of 103 countries had mid-range scores, including Brazil (0.65), South Africa (0.62), Japan (0.61), Liberia (0.57), Indonesia (0.55), Guatemala (0.57) and Timor-Leste (0.52). The remaining 44 countries fell in the high range, including Israel (0.71), Uruguay (0.74), Taiwan (0.75), Canada (0.76), Barbados (0.82) and Finland (0.87).

Countries in the top 20 scores for Gender Equality are primarily found in Europe, Asia and the Pacific, and Latin America and the Caribbean, while those in the bottom 20 include countries from Asia and the Pacific, Western Asia, Africa, and Latin America and the Caribbean (Figure 3.1).

A decade into the 2030 Agenda, and 30 years after the Beijing Declaration, the findings of this analysis paint a sobering picture of global progress on SDGs 5 and 16, goals that lie at the heart of inclusive, peaceful and resilient societies. Data from International IDEA’s Global State of Democracy Indices shows that democratic backsliding and the erosion of rights and institutions are undermining not only the integrity of governance systems but also the advancement of gender equality. While there are some areas of modest progress, such as improvements in women’s parliamentary representation and anti-corruption measures, these are overshadowed by widespread and multidimensional setbacks. Scores have declined across all core democratic indicators under SDG 16, especially in Representation, Participation and Rule of Law, with troubling regional trends driven by conflict, autocratization and shrinking civic space.

Equally concerning is the uneven and fragile progress on SDG 5. Although 10 countries have seen some statistically significant improvement in Gender Equality since 2015, the pace has slowed significantly, and in some regions—especially Asia and the Pacific, Southern Africa and North America—Gender Equality scores have regressed. Conflict-affected countries like Afghanistan, Palestine and Syria have witnessed large percentage declines, while even mid- and high-income countries like Hungary and the Philippines show signs of gender regression tied to democratic backsliding and legal setbacks. Gains made through reforms—such as gender quotas or legal protections—often remain superficial or vulnerable to reversal when institutions are weak or political will is lacking.

The interdependence of gender equality and democratic governance is clear. Where democracy erodes, women’s rights are often among the first casualties. Violence against women in politics, restrictions on civil society and shrinking freedoms of expression not only harm individual women but also corrode the foundations of equitable and representative systems. At the same time, progress on SDGs 5 and 16 remains indispensable for realizing the entire 2030 Agenda. Without gender-equal institutions and inclusive democratic participation, broader development gains risk faltering further.

Recent foreign-aid cuts risk exacerbating democratic backsliding and gender inequality by weakening the institutions and civil society actors crucial to upholding SDGs 5 and 16. To reverse these trends, a renewed global commitment and targeted investment are essential. Donors, governments and multilateral institutions must place democratic resilience and gender equality at the centre of development strategies. This means protecting civic space, strengthening institutions, investing in women’s organizations and democratic actors, and ensuring that laws and policies translate into transformative change. The next five years will be decisive: without bold and sustained action, the promise of the 2030 Agenda risks slipping permanently out of reach.

This paper was conceptualized and written by Annika Silva-Leander and Amanda Sourek. We would like to sincerely thank Emily Bloom and Irene Postigo Sanchez at International IDEA for their work in collecting the Global State of Democracy data that made this analysis possible. The peer reviewers of this paper also deserve recognition for their invaluable input, including Alexander Hudson (International IDEA) and Alexandra Wilde (United Nations Development Programme).

We would also like to thank Lisa Hagman for her editorial guidance and support in the design of this paper.

Abbasi, F., ‘For Afghan women, singing is resistance’, Kabul Now, 28 August 2024, <https://kabulnow.com/2024/08/for-afghan-women-singing-is-resistance>, accessed 24 June 2025

AP News, ‘The Taliban say they will close all NGOs employing Afghan women’, 30 December 2024, <https://apnews.com/article/afghanistan-taliban-ngo-women-closure-1fde989369785f8df0e83c81d48626f1>, accessed 25 June 2025

Asplund, E., Bicu, I., Campion, S., Garnett, H. A., Harty, M., James, T. S., Olafsdottir, G., Pearce Laanela, T., Thalin, J. and Vashchanka, V., Review of the 2024 Super-Cycle Year of Elections: Trends, Challenges and Opportunities (Stockholm: International IDEA, 2025), <https://doi.org/10.31752/idea.2025.22>

Barr, H., ‘The Taliban and the global backlash against women’s rights’, Georgetown Journal of International Affairs, 6 February 2024, <https://gjia.georgetown.edu/2024/02/06/the-taliban-and-the-global-backlash-against-womens-rights>, accessed 24 June 2025

Childs Daly, S. F., ‘Military rule is on the rise in Africa – nothing good came from it in the past’, The Conversation, 20 November 2024, <https://theconversation.com/military-rule-is-on-the-rise-in-africa-nothing-good-came-from-it-in-the-past-242219>, accessed 25 June 2025

Christensen, S., ‘Gambia parliament rejects bill to end ban on female genital mutilation’, Reuters, 15 July 2024, <https://www.reuters.com/world/africa/gambia-parliament-rejects-bill-unban-female-genital-mutilation-speaker-says-2024-07-15>, accessed 24 June 2025

CIVICUS, ‘Who bears the brunt’, in ‘People Power Under Attack 2024’, CIVICUS Monitor, December 2024, <https://monitor.civicus.org/globalfindings_2024/whobearsthebrunt>, accessed 3 July 2025

Council of Europe, ‘The Republic of Moldova ratifies the Istanbul Convention’, 31 January 2022, <https://www.coe.int/en/web/istanbul-convention/-/the-republic-of-moldova-ratifies-the-istanbul-convention>, accessed 25 June 2025

—, ‘New report indicates “shrinking space” for women’s rights defenders’, 13 May 2025, <https://www.coe.int/en/web/portal/-/new-report-indicates-shrinking-space-for-women-s-rights-defenders-1>, accessed 25 June 2025

Freedom House, ‘Freedom in the World’, [n.d.], <https://freedomhouse.org/report/freedom-world#Data>, accessed 25 June 2025

Gambia, Republic of The, Ministry of Gender, Children and Social Welfare, ‘National Gender Policy 2025-2034’, 7 June 2024, <https://policies.gov.gm/f/4abc2f7e-13ad-11f0-b086-029254d29bb1>, accessed 24 June 2025

Gender Links, ‘50/50 Policy Brief: Madagascar – Challenges To Achieving Gender Parity in Political Representation’, November 2020, <https://genderlinks.org.za/wp-content/uploads/2020/11/50-50-PB-MADA-NOV2020rev3.pdf>, accessed 2 July 2025

Global Democracy Coalition, ‘Survey on Impact of US Foreign Assistance Cuts on DRG Programming’, 1 July 2025, <https://globaldemocracycoalition.org/survey-on-impact-of-us-foreign-assistance-cuts-on-drg-programming>, accessed 24 June 2025

Haynes, S., ‘Costa Rica becomes first Central American country to legalize same-sex marriage’, Time, 26 May 2020, <https://time.com/5842537/costa-rica-legalizes-same-sex-marriage/>, accessed 24 June 2025

Human Rights Watch, ‘Myanmar: Year of brutality in coup’s wake’, 28 January 2022, <https://www.hrw.org/news/2022/01/28/myanmar-year-brutality-coups-wake>, accessed 25 June 2025

International IDEA, Gender Quotas Database, ‘Costa Rica’, [n.d.a], <https://www.idea.int/data-tools/data/gender-quotas-database/country?country=54>, accessed on 24 June 2025

—, Global State of Democracy Indices, [n.d.b], <https://www.idea.int/democracytracker/gsod-indices>, accessed 24 June 2025

—, Inclusion Portal, National Frameworks, ‘Egypt’, [n.d.c], <https://www.idea.int/inclusion-portal/portal/national_frameworks/EG>, accessed 24 June 2025

—, The 2024 Global Elections Super-Cycle, [n.d.d], <https://www.idea.int/initiatives/the-2024-global-elections-supercycle>, accessed 25 June 2025

—, The Sustainable Development Goals and the GSOD Indices, Revised Edition, GSoD In Focus No. 15 (Stockholm: International IDEA, 2023), <https://doi.org/10.31752/idea.2023.103>

—, The Global State of Democracy 2024: Strengthening the Legitimacy of Elections in a Time of Radical Uncertainty (Stockholm: International IDEA, 2024), <https://www.idea.int/gsod/2024>, accessed 25 June 2025

Inter-Parliamentary Union (IPU), IPU Parline, ‘Global and regional averages of women in national parliaments’, [n.d.a], <https://data.ipu.org/women-averages/?date_month=4&date_year=2025>, accessed 24 June 2024

—, IPU Parline, ‘Monthly ranking of women in national parliaments’, [n.d.b], <https://data.ipu.org/women-ranking/>, accessed 24 June 2025

—, ‘Women in National Parliaments’, 1 September 2015, <http://archive.ipu.org/wmn-e/arc/world010915.htm>, accessed 24 June 2025

Laneuville, H. and Possebom, V., ‘Fight like a woman: Domestic violence and female judges in Brazil’, arXiv, 12 May 2024, <https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2405.07240>

Minard, N. and Carmo, A., ‘Mexico: Boom in organised crime making femicide invisible, local activist says’, United Nations News, 5 December 2024, <https://news.un.org/en/story/2024/12/1157811>, accessed 24 June 2025

Mordt, M. and Rikanovic, M., ‘The road ahead for gender equality for ALL women and girls’, United Nations Serbia, 8 March 2025, <https://serbia.un.org/en/292009-road-ahead-gender-equality-all-women-and-girls>, accessed 24 June 2025

Peyton, B., Bajjalieh, J., Martin, M., Alahi, S., Fadell, N. and Jeralds, M., Cline Center Coup d’État Project Dataset, Version 8, University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign, 30 January 2025, <https://doi.org/10.13012/B2IDB-9651987_V8>

Silva-Leander, A., Beijing+30: Taking Stock of Progress on Gender Equality Using the Global State of Democracy Indices, Technical Paper (Stockholm: International IDEA, 2025), <https://doi.org/10.31752/idea.2025.12>

Tianjoky, A. A., ‘Malagasy praise government efforts to promote gender equality but want to see more’, Afrobarometer, Dispatch No. 795, 16 April 2024, <https://www.afrobarometer.org/publication/ad795-malagasy-praise-government-efforts-to-promote-gender-equality-but-want-to-see-more>, accessed 24 June 2025

United Nations Development Programme (UNDP), ‘2023 Gender Social Norms Index: Breaking Down Gender Biases. Shifting Social Norms Towards Gender Equality’, 12 June 2023, <https://hdr.undp.org/content/2023-gender-social-norms-index-gsni#/indicies/GSNI>, accessed 24 June 2025

United Nations General Assembly, ‘Promotion and protection of the right to freedom of opinion and expression’, Resolution A/76/258, 30 July 2021, <https://documents.un.org/doc/undoc/gen/n21/212/16/pdf/n2121216.pdf>, accessed 3 July 2025

United States Institute of Peace (USIP), Tracking the Taliban’s (Mis)Treatment of Women, [n.d.], <https://www.usip.org/tracking-talibans-Mistreatment-women>, accessed 24 June 2025

UN Women, Women’s Rights in Review 30 Years after Beijing (New York: UN Women, 2025a), <https://www.unwomen.org/sites/default/files/2025-03/womens-rights-in-review-30-years-after-beijing-en.pdf>, accessed 24 June 2025

—, ‘Three years of full-scale war in Ukraine roll back decades of progress for women’s rights, safety and economic opportunities’, 19 February 2025b, <https://www.unwomen.org/en/news-stories/press-release/2025/02/three-years-of-full-scale-war-in-ukraine-roll-back-decades-of-progress-for-womens-rights-safety-and-economic-opportunities>, accessed 24 June 2025

UN Women Egypt, Leadership and Political Participation, [n.d.], <https://egypt.unwomen.org/en/what-we-do/leadership-and-political-participation-4>, accessed 24 June 2025

UN Women Europe and Central Asia, Moldova, [n.d.a], <https://eca.unwomen.org/en/where-we-are/moldova>, accessed 25 June 2025

—, Serbia, [n.d.b], <https://eca.unwomen.org/en/where-we-are/serbia_europe>, accessed 24 June 2025

—, ‘Moldova takes historic step to promote gender equality in politics’, 20 June 2016, <https://eca.unwomen.org/en/news/stories/2016/06/moldova-takes-historic-step-to-promote-gender-equality-in-politics>, accessed 25 June 2025

van Baalen, S., ‘Polls of fear? Electoral violence, incumbent strength, and voter turnout in Côte d’Ivoire’, Journal of Peace Research, 61/4 (2023), pp. 595–611, <https://doi.org/10.1177/00223433221147938>

World Bank, Gender Data Portal, Moldova, [n.d.], <https://genderdata.worldbank.org/en/economies/moldova>, accessed 25 June 2025

—, Unlocking the Potential of Women and Adolescent Girls: Challenges and Opportunities for Greater Empowerment of Women and Adolescent Girls in Madagascar (Washington, DC: World Bank Group, 2023), <https://openknowledge.worldbank.org/handle/10986/40427>, accessed 24 June 2025

Yefet, B. and Friedberg, C., ‘Media representation of members of parliament in Egypt: A reality of gender imbalance’, Digest of Middle East Studies, 33/4 (2024), pp. 361–84, <https://doi.org/10.1111/dome.12336>

© 2025 International Institute for Democracy and Electoral Assistance

International IDEA publications are independent of specific national or political interests. Views expressed in this publication do not necessarily represent the views of International IDEA, its Board or its Council members.

With the exception of any third-party images and photos, the electronic version of this publication is available under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 (CC BY-NC-SA 4.0) licence. You are free to copy, distribute and transmit the publication as well as to remix and adapt it, provided it is only for non-commercial purposes, that you appropriately attribute the publication, and that you distribute it under an identical licence. For more information visit the Creative Commons website: <http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/4.0>.

Cover illustration: AI generated with Adobe Firefly

Copyeditor: Curtis Budden

Design and layout: International IDEA

DOI: <https://doi.org/10.31752/idea.2025.42>

ISBN: 978-91-7671-973-2 (PDF)

ISBN: 978-91-7671-974-9 (HTML)