Amazonian Climate Deliberation

Insights from Three Citizen Assemblies on Climate Finance Held Ahead of COP30

While the need for effective climate action continues to rise, governance responses remain insufficient to meet the Paris Agreement goals. Climate assemblies, where citizens learn about and deliberate on policy recommendations, have the potential to address governance challenges by strengthening the legitimacy and raising the ambition of climate action while grounding it in the experience of those affected by climate impacts.

Ahead of the United Nations Climate Change Conference (COP30) that will take place in Belém, Brazil, in November 2025, this case study report contributes to ongoing efforts to pilot citizen deliberation and explore options for its integration into climate decision-making processes across the globe. It shares insights, challenges and possible impacts from three climate assemblies held in the Amazon region of Pará, in Brazil, by the non-profit organization Delibera Brasil.

The climate assemblies in Bujaru, Barcarena and Magalhães Barata engaged citizens in discussions on local climate priorities and access to climate finance, of which the latter remains a central challenge for Amazonian stakeholders working on local climate adaptation. The report argues for the potential of citizen deliberation to improve the access to, accountability in and legitimacy of climate finance if climate assemblies are organized in supportive contexts that ensure political support and financing for citizens’ recommendations that emerge out of them.

Drawing on the experiences of the three climate assemblies, the report offers insights into their design, implementation and policy outcomes:

- The climate assemblies provided inclusive spaces for citizens and diverse stakeholders to connect and produce shared agendas and local initiatives, creating legitimacy and fostering political and policy impacts that go beyond the recommendations produced.

- Deliberating on existing institutional governance arrangements and identifying gaps produced actionable recommendations to improve local governance frameworks.

- The climate assemblies in Pará managed to leverage political commitment and ensure systemic support—for instance, through the integration and participation of duty-bearers at the Magalhães Barata assembly, which strengthened the deliberation process and increased the likelihood of follow-through on the assembly’s recommendations.

- Engaging Indigenous and traditional communities through active and purposeful inclusion in the preparations for and implementation of the assemblies grounded the deliberation in the local context and added relevance and legitimacy to the process and its outcomes.

- Planning and designing the climate assemblies together with municipal and state government officials facilitated a shared understanding of climate challenges between citizens who experience these challenges and those tasked with the mandate to address them.

The citizen deliberation on Amazonian climate finance generated seven recommendations for climate finance ecosystems at local, national and global levels outlined in the final report chapter. These ranged from topics of climate finance participation, decision making, and strategic dialogue to management practices and sustainability of climate funds programmes and public policies.

Sophie Jahns and Elin Westerling

The natural world we all depend on is under severe pressure—pressure our governance systems are failing to deal with. At the moment of writing, seven of the nine planetary boundaries1 have been breached, putting the stability and resilience of our societies at critical risk (Planetary Boundaries Science 2025). Across the globe, people are increasingly concerned about the unfolding climate crisis. Yet, for many reasons, these concerns are not translating into effective climate action. To achieve the net-zero transition and meet the Paris Agreement goals, we need to significantly increase climate ambition. One important element necessary to reach a political consensus around climate policies is democratic governance innovations which better connect citizens with decision makers. Citizen deliberation, through forums such as climate assemblies, is a leading example of such democratic innovation (Lindvall 2021; Curato et al. 2024).

A climate assembly is a group of citizens selected through a representative sortition process, or lottery, who come together to learn, deliberate and agree on policy recommendations related to climate change. These three core phases—learning, deliberation and decision making—were a part of all three citizen assemblies described in this report.

Climate assemblies have the potential to strengthen the legitimacy and ambition of climate action, and hearing ideas and experiences from people directly affected by the climate crisis can improve the quality, accountability and sustainability of climate policies. At the same time, climate assemblies can improve democratic resilience by empowering citizens, reducing polarization, decentring elite control, and building the deliberative and participatory capacities of communities (Curato et al. 2024).

Key to successful climate deliberation is adapting practices to local contexts. In 2024, International IDEA and Agence Francaise de Développement published the report Deliberative Democracy and Climate Change: Exploring the Potential of Climate Assemblies in the Global South, which connected climate deliberation practices with participatory traditions in the Global South. The report made it clear that climate deliberation is a dynamic practice, capable of solving problems and advancing decision making on difficult political issues in many different contexts. It showed how the most successful deliberative processes are those which manage to take into consideration local customs, the socio-political environment and pre-existing participation constraints. Two of the central messages of the report were that there is a need for more South–South and South–North dialogues around climate deliberation and that there is value in building stronger international networks of practitioners and policymakers.

This case study report takes a step in that direction. It describes three climate assemblies piloted in the Amazon region of Pará, in Brazil, by Delibera Brasil. By telling the story of these assemblies, the report aims to contribute to efforts to pilot citizen deliberation and to understand how to integrate it into existing decision-making processes. The goal is to strengthen transparent, participative, accountable, and inclusive climate and environmental decision making while reflecting on how climate deliberation can contribute to longer-term institutional development and democracy building.

Brazil is a particularly interesting and relevant country for climate deliberation. As one of the world’s largest and most diverse democracies, and with a strong tradition of participatory governance, it has proven to be a fertile ground for democratic innovations. At the same time, Brazilian politics has in recent years been associated with growing polarization, corruption and inequality (International IDEA n.d.). Brazil is home to some 60 per cent of the Amazon rainforest, which makes it a key country in the global fight against climate change. The integrity of the Amazon biome is vital for the Earth’s stability, and continued deforestation could push the rainforest past a tipping point, with severe consequences far beyond the region (Planetary Boundaries Science 2025).

The Amazon rainforest is home to some 30 million people, among them many Indigenous, quilombola (descendants of formerly enslaved peoples) and other traditional communities. This diversity makes for a complex social, ecological and political situation, with opposing interests between extractivist economic development and the protection of Indigenous land rights, between deforestation and the safeguarding of natural resources, and between threats to traditional ways of life and strong social movements to protect local livelihoods. In this context, it is crucial to foster a sustainable economy that benefits both local communities and the natural environment. Inclusive citizen deliberation has the potential to help solve difficult challenges and find acceptable trade-offs, develop joint solutions and establish priorities, and collectively mobilize funding for climate adaptation (see Chapter 1: Citizen participation and deliberation for inclusive climate finance).

The three climate assemblies took place in Pará, the second-largest state in Brazil and the most populous state in the Amazon. The three municipalities selected to host the assemblies differ in terms of their geography, economy and cultural diversity, while they face similar challenges from extractivism and deforestation. The assemblies took place in 2024 and 2025, a period with strong momentum for climate change issues, with Brazil preparing to host the United Nations Climate Change Conference (COP30) in Belém, Pará, in November 2025. The first climate assembly was held in Bujaru (see Chapter 2: Case study: The Bujaru climate assembly) and focused on how to achieve a sustainable local bioeconomy. Among many important findings, it identified access to climate finance as one of the biggest challenges to local climate action and proposed it as a priority topic for citizen deliberation. Consequently, two more climate assemblies were organized, in Barcarena (see Chapter 3: Case study: The Barcarena climate assembly) and Magalhães Barata (see Chapter 4: Case study: The Magalhães Barata climate assembly). At the latter two assemblies, citizens were invited to deliberate and prioritize among local climate finance needs and discuss how to access climate finance for their communities.

All three climate assemblies offer important lessons, both through the citizens’ recommendations developed and delivered to local policymakers and for making the local decision-making process more inclusive and participatory. They also offer important insights beyond their local contexts by showcasing how to organize and leverage citizen deliberation on climate finance matters.

References Introduction

Curato, N., Smith, G., Willis, R. and Rosén, D., Deliberative Democracy and Climate Change: Exploring the Potential of Climate Assemblies in the Global South (Stockholm: International IDEA and Agence Francaise de Développement, 2024), <https://doi.org/10.31752/idea.2024.34>

International IDEA, Democracy Tracker: Brazil, [n.d.], <https://www.idea.int/democracytracker/country/brazil>, accessed 20 October 2025

Lindvall, D., Democracy and the Challenge of Climate Change, International IDEA Discussion Paper 3/2021 (Stockholm: International IDEA, 2021), <https://doi.org/10.31752/idea.2021.88>

Planetary Boundaries Science, Planetary Health Check 2025: A Scientific Assessment of the State of the Planet (Potsdam, Germany: Potsdam Institute for Climate Impact Research, 2025), <https://www.planetaryhealthcheck.org/#reports-section>, accessed 20 October 2025

Anoukh de Soysa

1.1. Climate finance and the integrity imperative

Climate finance broadly refers to local, national or transnational funding that supports climate change mitigation and adaptation efforts (UNFCCC n.d.). As the world prepares for the United Nations Climate Change Conference (COP30) in Belém, Brazil, discussions around the mobilization and governance of climate finance have become prominent. While rapidly increasing the volume of funding remains essential to tackling the climate crisis, the way this funding is governed, including how decisions are made and by whom, is equally central to the success and legitimacy of climate initiatives (Shutt 2022; Foti and Socci 2023; de Soysa 2025).

The landscape of climate finance today forms a diverse and multilayered ecosystem that encompasses global climate funds, multilateral development banks, bilateral arrangements, domestic mechanisms and the private sector. As the climate crisis deepens, and the demand for climate finance escalates, strong integrity measures2 to safeguard such finance from misallocation and misuse become imperative (UNDP 2024). The principles of transparency, public participation and accountability can no longer be mere aspirations. These governance and integrity guardrails must be the cornerstones of climate finance, paving the way for a just transition to a more sustainable global economy.

This chapter explores the role of participation and deliberative mechanisms in advancing this integrity imperative. First, it examines how public participation can enhance the transparency, oversight and legitimacy of climate finance by linking individuals, communities and civil society to key decision-making and monitoring processes. It then discusses the promise and pitfalls of climate assemblies, situating these innovative, deliberative tools within the landscape and context of climate finance.

1.2. Public participation in climate finance

Public participation involves the direct engagement of individuals, communities and civil society in public policy (de Soysa 2022b). In climate governance, this participation typically entails public engagement and deliberation in the design, allocation, implementation, monitoring and evaluation of climate finance and investments. Public participation can also take many different forms. While elections represent the most common and fundamental form, democracy beyond the ballot box can range from ad hoc public hearings and consultations to more systematic or institutional processes (de Soysa 2022b).

Climate assembly in Bujaru, March 2024

The growing appeal of public participation in climate finance rests on evidence of its transformative potential. According to surveys by Bernauer and Gampfer (2013), for instance, the popular legitimacy of, and thereby public trust in, global climate and environmental governance and policy significantly increases when civil society is included in the process. This finding was confirmed in a study by Cabannes (2021) which found that meaningful public participation in the allocation and use of climate funds and resources can not only strengthen public support but may also contribute to more efficient and responsive use of these funds. Similarly, the Open Government Partnership’s guide on climate and environment notes that opportunities for participation help better direct funds towards public priorities, adding that, through inclusive climate finance, governments can support greater climate resilience among those who are most vulnerable to climate change (Foti and Socci 2023).

Despite its many benefits, public participation does not arise or occur in a vacuum (Wampler and Touchton 2017). Meaningful participation requires enabling structures, processes and conditions that facilitate accessible and inclusive spaces (de Soysa 2022b). These conditions include transparency and access to information, appropriate legal mandates, facilitative operational frameworks, the functioning of an organized civil society within a supportive civic space and, crucially, the political capacity and willingness to engage with the public (de Soysa 2022c).

In the absence of these enabling conditions, participatory initiatives are less likely to succeed. Often, and especially in the context of climate governance, participation is encumbered by complex power asymmetries and incentives (de Soysa and Halloran 2025). These asymmetries, in turn, compromise the ability of communities and civil society to influence decisions and thus limit inclusive access to climate finance and resources (Pant 2024). In such circumstances, even if funding does reach local communities, it remains challenging to ensure that it benefits the most vulnerable or historically excluded groups (Shutt 2022). This is where public oversight and accountability can step in.

1.3. From public participation to public oversight

Democratic accountability entails citizens’ ability to articulate demands to influence decision making (Bjuremalm, Gibaja and Molleda 2014). It is an all-encompassing notion that includes different forms of social accountability or public oversight, political and institutional checks and balances, investigative journalism, legislative initiatives and even public debate. Within this broader accountability umbrella, public oversight, bolstered by transparency and participation, forms the bedrock of a successful climate finance framework. Premised around the idea of demanding answers and enforcing action, public oversight of climate finance can take many forms, ranging from a variety of social accountability tools, such as participatory budgeting, citizen report cards and social audits, used at different stages of the climate finance cycle, to more deliberative processes and mechanisms such as climate assemblies.

Where transparency and participation alone fall short of enabling inclusive and impactful climate finance, public oversight approaches can play a pivotal, complementary role. In fact, combining oversight with transparency and participation has been found to strengthen the integrity of climate spending, reduce leakages in climate funds (Patel et al. 2022), limit the loss of climate finance to corruption (Fritz and Anderson 2023), prevent financing processes from being captured by private and vested interests, improve economic returns on climate investments (NDC Partnership 2021), and generally enhance the effectiveness and efficiency of climate efforts (IPCC 2023; de Soysa and Halloran 2025; Glencorse and Jarvis 2025).

Essentially, a comprehensive governance and integrity ecosystem can help elevate flexible notions of accountability from procedural, bureaucratic reporting to deliberative oversight, where civil society, as well as affected individuals and communities can shape and influence how climate finance is mobilized and used. In Nepal, for example, a national civil society organization built on the existing participatory mechanism of public hearings at the local government level to establish multistakeholder action groups to serve as watchdogs and demand accountability on climate finance (Shutt 2022; Foti and Socci 2023).

As climate finance expands in scale and complexity, integrity frameworks and solutions must evolve from technical safeguards into inclusive, deliberative processes that deepen democratic legitimacy. The following sections explore the extent to which climate assemblies can offer a viable solution.

1.4. The promise and pitfalls of climate assemblies

Climate assemblies are deliberative forums that convene randomly selected, yet demographically representative, individuals to ‘learn, deliberate, and agree on recommendations on aspects of the climate and ecological crisis’ (Curato et al. 2024: 26). Reflective of a ‘deliberative wave’ (OECD 2020), the proliferation of these assemblies, particularly in Europe, has sparked significant interest in their potential to democratize complex governance processes, strengthen legitimacy and raise climate ambition (Meija 2023; Bouyé and Excell 2024; Curato et al. 2024).

In the lead-up to COP30, this deliberative wave has taken on larger proportions. Building on similar experiences at COP26 (Global Assembly 2022), the Coalition for a Global Citizens’ Assembly is currently uniting governments, organizations, individuals and communities through a series of climate assemblies around the world (Global Citizens’ Assembly 2025). This global mutirão (collective effort), backed by the Brazilian COP presidency, aims to influence climate negotiations and hold leaders accountable for climate commitments, actions and results (Wilson and Levaï 2025).

The mutirão presents a timely opportunity to reframe and reinvigorate global climate governance by placing people at the centre of climate deliberations. As noted later in this report, however, climate assemblies grapple with challenges that limit their ability to turn local ideas into global reforms. Central to these challenges are questions of political support, conflicts, power asymmetries and the availability of resources (i.e. climate finance), which undermine the inclusivity of assemblies; give the experts facilitating them disproportionate decision-making power; and generally diminish the authority, legitimacy and capacity of assemblies to drive impactful change (Bouyé and Excell 2024; Rosignoli 2025).

While facilitation strategies and techniques can help orient deliberations more equitably (Curato et al. 2024; Rosignoli 2025), realizing the promise of climate assemblies requires more systemic support. Linking the governance prerogative and participatory potential of assemblies to the broader ecosystem of climate finance, connecting deliberated solutions with resources, offers a compelling way forward.

1.5. Climate assemblies and climate finance: By the people, for the planet

The effectiveness of climate finance in addressing the climate crisis hinges on the guardrails of a transparent, inclusive, participatory and accountable governance framework. Climate assemblies, when endowed with legitimacy, authority and resources, stand to offer these safeguards and, in doing so, help ensure that climate investments reach those who need them most. All too often, however, climate assemblies and other deliberative forums navigate entrenched power dynamics, resource limitations and political inertia that restrict their legitimacy and impact.

Beyond procedural and technical solutions, overcoming these challenges requires climate assemblies to tap into a repertoire of tested strategies to engage duty-bearers3 and foster institutional support. These strategies include working with supportive champions within public service, leveraging political entry points such as elections, forming organizational coalitions to advocate for reform and escalating intractable issues to global or multilateral platforms (de Soysa 2022a). Building on this strategic premise, the infrastructure and ecosystem of climate finance offer critical levers for climate assemblies to address power asymmetries, access essential resources and catalyse political appetite for reform.

The first lever is the use of global climate funds and financial flows to support the implementation of ideas and recommendations emerging from climate assemblies. This connection can help channel resources into locally endorsed climate projects and strengthen public trust in the potential impact of deliberative governance. As key sources of global climate finance recognize the value and returns on investment from locally based and locally led solutions (Green Climate Fund 2023; Adaptation Fund 2024), the case for channelling financial support to inclusive, local climate assemblies grows clearer. The Green Climate Fund, for example, is currently holding consultations to embed deliberative and participatory approaches in both its policy and project-level decisions through the development of a locally led climate action framework and guidelines (Calin and Holganza 2025).

In many countries and contexts, however, local access to multilateral climate finance is compounded by a lack of capacity to meet the prerequisite appraisal criteria to manage international funds (Fouad et al. 2021). Across the board, multilateral funds call for robust governance safeguards and stringent public financial management standards that a significant proportion of governments and organizations would be stretched too far to meet (Browne 2022). At the same time, these requirements incentivize entities to establish or strengthen transparency, participation and accountability frameworks, building support and momentum for institutionalizing deliberative mechanisms such as climate assemblies. Improving financial management, governance and integrity in this manner can lead to greater investor confidence, unlocking a raft of funding opportunities, even beyond multilateral funds.

The second lever, closely linked to the first, involves harnessing climate investments to strengthen the governance structures and systems that support climate assemblies. When a climate fund or other source of climate finance makes an investment to implement an assembly’s recommendations, the associated accountability and oversight mechanisms naturally extend to the deliberative process and its outcomes. This means that the strong checks and balances inherent in financial investments can be extended to the deliberation process, helping to ensure that assemblies remain accountable, not only in delivering a transparent and inclusive deliberation process but also for following through on the recommendations and promises they elicit. In connecting assemblies to financial oversight processes, climate financing can also help address power asymmetries inherent in localized, siloed assemblies.

This second lever creates an accountability loop, where climate finance can turn transparent, inclusive and accountable deliberation into transparent, inclusive and accountable actions. If deliberative mechanisms such as climate assemblies are then institutionalized across the life cycle of financed climate projects (i.e. informing their design, implementation and evaluation), the independent oversight and commitment to governance they offer can help minimize risks of loss or misuse of climate finance.

The success of climate finance remains contingent on how well it is governed. Beyond simple metrics of financial integrity, the principles of transparency, public participation and accountability form the basis of an ecosystem that centres procedural justice and democratic legitimacy. At their best, climate assemblies exemplify the promise of this governance framework by providing structured, inclusive and deliberative spaces where the voices of those most affected can shape decisions. As the world advances towards a just transition, climate action can no longer be judged by efficiency alone. Empowered with accountability, legitimacy and adequate resources, climate assemblies hold the potential to ensure that climate finance is governed by the people, for the planet.

References Chapter 1

Adaptation Fund, ‘Additional Delivery Modalities for Expanding Support to Locally Led Adaptation’, AFB/PPRC.33/39, 30 March 2024, <https://www.adaptation-fund.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/AFB.PPRC_.33_39.pdf>, accessed 31 October 2025

Bernauer, T. and Gampfer, R., ‘Effects of civil society involvement on popular legitimacy of global environmental governance’, Global Environmental Change, 23/2 (2013), pp. 439–49, <https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2013.01.001>

Bjuremalm, H., Gibaja, A. F. and Molleda, J. V., Democratic Accountability in Service Delivery: A Practical Guide to Identify Improvements through Assessment (Stockholm: International IDEA, 2014), <https://www.idea.int/publications/catalogue/democratic-accountability-service-delivery-practical-guide-identify>, accessed 31 October 2025

Bouyé, M. and Excell, C., Citizens’ Assemblies and the Climate Emergency: Lessons for Design to Enhance Climate Action (Washington, DC: World Resources Institute, 2024), <doi.org/10.46830/wrirpt.20.00118>

Browne, K., ‘The Paris Agreement depends on improving accountability in climate finance’, Stockholm Environment Institute, 13 January 2022, <https://www.sei.org/perspectives/accountability-climate-finance/>, accessed 17 October 2025

Cabannes, Y., ‘Contributions of participatory budgeting to climate change adaptation and mitigation: Current local practices across the world and lessons from the field’, Environment & Urbanization, 33/2 (2021), pp. 356–75, <https://doi.org/10.1177/09562478211021710>

Calin, R. and Holganza, A., ‘Locally Led Climate Action: Framework and Guidelines’, Green Climate Fund, Presentation at an engagement with accredited observers, 18 September 2025, <https://www.greenclimate.fund/sites/default/files/event/gcf-llca-guidelines-slide-deck-18-sep.pdf>, accessed 30 October 2025

Curato, N., Smith, G., Willis, R. and Rosén, D., Deliberative Democracy and Climate Change: Exploring the Potential of Climate Assemblies in the Global South (Stockholm: International IDEA and Agence Francaise de Développement, 2024), <https://doi.org/10.31752/idea.2024.34>

de Soysa, A., ‘Engaging Reluctant Duty-Bearers’, Transparency International, 31 January 2022a, <https://knowledgehub.transparency.org/product/engaging-reluctant-duty-bearers-considerations-and-strategies-for-civil-society-organisations>, accessed 1 October 2025

—, ‘Participatory Budgeting: Public Participation in Budget Processes’, Transparency International, 29 March 2022b, <https://knowledgehub.transparency.org/product/participatory-budgeting-a-primer-on-public-participation-in-budget-processes>, accessed 1 October 2025

—, ‘Assessing Public Participation in Budget Processes: Assessment Toolkit & Indicators’, Transparency International, 23 December 2022c, <https://knowledgehub.transparency.org/product/assessing-public-participation-in-budget-processes-assessment-toolkit-indicators>, accessed 31 October 2025

—, ‘Strengthening public oversight in climate initiatives’, Transparency International, 24 July 2025, <https://www.transparency.org/en/blog/strengthening-public-oversight-in-climate-initiatives>, accessed 1 October 2025

de Soysa, A. and Halloran, B., ‘Climate accountability: Beyond transparency and public participation’, Transparency International, 9 October 2025, <https://www.transparency.org/en/blog/going-beyond-transparency-and-public-participation-in-climate-initiatives>, accessed 1 October 2025

Foti, J. and Socci, C., ‘Climate and environment’, in The Open Gov Guide 2024 (Open Government Partnership, 2023), <https://www.opengovpartnership.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/11/Open-Gov-Guide-2024-Full-Report.pdf>, accessed 31 October 2025

Fouad, M., Novta, N., Preston, G., Schneider, T. and Weerathunga, S., Unlocking Access to Climate Finance for Pacific Island Countries, Departmental Papers 2021/020 (Washington, DC: International Monetary Fund, September 2021), <https://doi.org/10.5089/9781513594224.087>

Fritz, A. and Anderson, J., ‘Seven ways to address corruption risks in climate change’, World Bank Blogs, 6 October 2023, <https://blogs.worldbank.org/en/governance/seven-ways-address-corruption-risks-climate-change>, accessed 9 October 2025

Glencorse, B. and Jarvis, M., ‘The Role of Civil Society Oversight and Social Accountability in Climate Finance and Action’, World Bank, April 2025, <https://www.worldbank.org/content/dam/documents/sanctions/other-documents/2025/apr/Glencorse.BJarvis.M.ClimateFinanceandSocialAccountability.pdf>, accessed 31 October 2025

Global Assembly, Report of the 2021 Global Assembly on the Climate and Ecological Crisis: Giving Everyone a Seat at the Global Governance Table (Global Assembly, 2022), <https://globalassembly.org/resources/downloads/GlobalAssembly2021-FullReport.pdf>, accessed 18 October 2025

Global Citizens’ Assembly, ‘COP30: Bringing citizens to the heart of climate negotiations’, 2025, <https://globalassemblies.org/cop30>, accessed 18 October 2025

Green Climate Fund, ‘Strategic Plan for the Green Climate Fund 2024–2027’, 13 July 2023, <https://www.greenclimate.fund/sites/default/files/document/strategic-plan-gcf-2024-2027.pdf>, accessed 31 October 2025

Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), Climate Change 2022: Impacts, Adaptation, and Vulnerability (Cambridge and New York: Cambridge University Press, 2023), <https://dx.doi.org/10.1017/9781009325844>

London School of Economics (LSE), ‘Integrity in Climate Finance & Action: Knowledge Report’, 2nd Symposium on Supranational Responses to Corruption, 2025, <https://www.lse.ac.uk/granthaminstitute/wp-content/uploads/2025/05/Integrity-in-Climate-Finance-and-Action-Knowledge-Report.pdf>, accessed 31 October 2025

Meija, M., ‘2023 trends in deliberative democracy: OECD Database update’, Participo, 7 December 2023, <https://medium.com/participo/2023-trends-in-deliberative-democracy-oecd-database-update-c8802935f116>, accessed 18 October 2025

NDC Partnership, ‘Principles and Recommendations on Access to Climate Finance’, UK Government, November 2021, <https://ndcpartnership.org/sites/default/files/2023-12/principles-and-recommendations-access-climate-finance.pdf>, accessed 18 October 2025

Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), Innovative Citizen Participation and New Democratic Institutions: Catching the Deliberative Wave (Paris: OECD Publishing, 2020), <https://www.oecd.org/gov/innovative-citizen-participation-and-new-democratic-institutions-339306da-en.htm>, accessed 19 October 2020

Pant, S., ‘Collective CSO action critical for climate justice’, Accountability Lab, 5 March 2024, <https://accountabilitylab.org/27550-2/>, accessed 31 October 2025

Patel, S., McCullough, D., Steele, P., Hossain, T., Damanik, I., Kartika, W., Guevarrato, G. C. and Sapkota, K., Public Participation in Climate Budgeting: Learning from Experiences in Bangladesh, Indonesia, and Nepal (London: International Institute for Environment and Development, 2022), <https://www.iied.org/21031iied>, accessed 31 October 2025

Rosignoli, F., ‘How to find consensus among citizens in the climate debate’, Eurac Research, 21 August 2025, <https://www.eurac.edu/en/blogs/connecting-the-dots/how-to-find-consensus-among-citizens-in-the-climate-debate>, accessed 11 October 2025

Shutt, C., ‘Climate Finance Accountability Synthesis Report’, International Budget Partnership, January 2022, <https://internationalbudget.org/wp-content/uploads/CFA-Synthesis-Report-16-05.pdf>, accessed 12 October 2025

United Nations Development Programme (UNDP), ‘Enhancing Transparency and Accountability of Domestic Climate Public Finance’, Climate Finance Network, Policy Brief, 2024, <https://www.undp.org/sites/g/files/zskgke326/files/2024-06/domestic_climate_public_finance_brief.pdf>, accessed 31 October 2025

United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC), ‘Introduction to climate finance’, [n.d.], <https://unfccc.int/topics/introduction-to-climate-finance>, accessed 7 October 2025

Wampler, B. and Touchton, M., ‘Participatory Budgeting: Adoption and Transformation’, Institute of Development Studies, Research Briefing, November 2017, <https://opendocs.ids.ac.uk/articles/report/Participatory_budgeting_adoption_and_transformation/26439868?file=48185764>, accessed 1 October 2025

Wilson, R. and Levaï, D., ‘How a new global citizens’ assembly can revive climate action’, European Democracy Hub, 12 February 2025, <https://europeandemocracyhub.epd.eu/how-a-new-global-citizens-assembly-can-revive-climate-action>, accessed 12 October 2025

Marcella Nery

2.1. Formulating the climate assembly remit for the people and context of Bujaru

In 2023, Delibera Brasil invited Amazonian municipalities4 to express their interest in holding a climate assembly to draw up recommendations for local climate adaptation and mitigation. After two rounds of assessment, Bujaru was selected from among the 16 municipalities that registered (from 6 of the 9 Brazilian states that form the region known as Amazônia Legal). Representatives of civil society organizations, leaders of social movements, researchers and specialists selected Bujaru because the challenges it is facing are similar to those affecting most Amazonian areas. The remit of the assembly—participating in the bioeconomy and maintaining biodiversity and quality of life—was formulated by the municipal secretary of agriculture in collaboration with civil society organizations, state bodies and experts. As such, the climate assembly addressed topics that are central to the residents of Bujaru.

The municipality, located in the state of Pará in the north of Brazil, is home to a wide diversity of traditional Indigenous, quilombola (Afro-Brazilian) and ribeirinho (riverside) communities, whose knowledge and ways of life help preserve biodiversity. ‘We are the sons and daughters of this land we call Bujaru’, said a member of the assembly in his opening speech, demonstrating that the rainforest and those who live in it are a focal point of the participants’ social identity.

Bujaru, March 2024

Another challenge for Bujaru lies in the local bioeconomy. ‘We are producers, açai producers’, said an assembly member, ‘the third largest in Brazil, but we could produce and sell better; we are in the hands of the middlemen.’ This statement describes a vicious circle: local producers lack the machinery and technical skills to process the açai, which makes them dependent on intermediaries who take a substantial portion of the profits. This decentralized trade also occurs outside of official revenue collection mechanisms, which prevents the wealth created from returning to the municipality in the form of taxes. Bujaru, while rich in biodiversity, is one of the 10 Brazilian municipalities most dependent on federal funds, highlighting the importance of a resilient bioeconomy for Bujaru.

The climate assembly took place within the framework of the

The governance of

2.2. Co-creating and implementing the climate assembly methodology

The assembly followed the traditional deliberative mini-public design, with phases focusing on recruitment, random selection, deliberation, and the drafting and adoption of recommendations. In 2024, the Delibera Brasil team sent out 200 invitation letters to randomly selected households and handed out invitations to 250 people at different places in the municipality. Forty-one per cent of the people invited registered for the random selection stage—a high acceptance rate for a citizens’ assembly, considering that 90 per cent of cases in the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development data set (up to 2025) report acceptance rates below 11 per cent (Spada and Peixoto 2025). Then, a stratified sample from the registrations based on age, gender, level of education, professional situation, geographical location, perception of climate change and membership of a traditional community was extracted.

Given the historical exclusion of traditional communities from state and corporate climate decision-making processes, the organizing team made a deliberate effort to ensure their meaningful representation in both assembly preparations and deliberation. Through a six-week preparation process, with additional institutional funding, the team visited 11 communities with the support of a local mobilizer to explain the concept of the climate assembly and the random selection process. These steps enabled the communities to shape the recruitment process by including quotas in the stratified random selection process. This arrangement ensured that the Indigenous, quilombola and ribeirinho communities were represented and participated as members of the climate assembly and its consultative group, as well as speakers, facilitation assistants and food suppliers.

The assembly took place over five weekends, with approximately 86 per cent of the group participating in at least four sessions. Each session focused on different topics: (a) exploring principles of deliberation and establishing connections among members; (b) discussing issues with state administrators responsible for bioeconomy planning and agricultural policies; (c) engaging with representatives of civil society and agro-ecological cooperatives, as well as planning a public event to connect the climate assembly recommendations with municipal council candidates; (d) assessing the responsibilities of different actors within the bioeconomy system and the regional funding opportunities; and (e) deliberating and agreeing on the final recommendations.

Bujaru, March 2024

2.3. Policy impact of the climate assembly recommendations

The climate assembly put forward 12 core recommendations (Delibera Brasil 2025), which included promoting the sustainable growth of family farming, creating a municipal cooperative for fruit and food processing, and reducing the use of pesticides associated with the palm oil industry. The Municipal Agriculture Secretariat, as the assembly’s proponent, incorporated some of these proposals into its bioeconomy plan, which provided a route for implementation. However, the municipal elections that took place at this critical moment altered the political backing of the plan and de-prioritized the legislative process for its approval. This course of events illustrates how the policy impact of climate assemblies can be weakened by changes in the political context.

Further implementation of the recommendations has been constrained by limited municipal financial resources rather than a lack of political will. The recommendations themselves represented shared citizen ambitions that transcended immediate budgetary constraints, articulating a broader vision for the municipality’s future. To mobilize the necessary funds, the municipality would need to establish tax collection mechanisms aligned with bioeconomy principles or secure external funding from federal, state or international sources. Delibera Brasil, public authorities and civil society representatives anticipated this funding challenge from the outset.

Bujaru’s selection to host the climate assembly was viewed positively by state officials. They recognized that citizen deliberation could generate clearer priorities to support funding applications, with the municipality already eligible for various opportunities. Importantly, while the state bioeconomy plan operated at a broad state level without regional differentiation, several assembly recommendations offered potential to help operationalize and ground the plan locally. Officials saw this as authentic civic participation that could enhance both funding strategies and policy implementation. While the sessions were taking place, France also announced a financial partnership with Brazilian public banks to raise EUR 1 billion (approximately USD 1.16 billion) to invest in the bioeconomy of the Amazonian region (Almeida 2024). This announcement sparked further expectations within the local community, with the mayor of Bujaru saying, ‘I would have no objections to implementing the assembly’s recommendations if some of that money gets here one day.’

However, even though the state of Pará is in an excellent position to access and redistribute climate funds to its municipalities, the volume of, and speed at which, these funds are raised is limited, and the resources remain concentrated in the ‘arc of deforestation’, the critical area for expanding the agricultural border. In municipalities like Bujaru, which are located outside of this priority area, the mechanisms available have proven to be insufficient. Payment programmes for environmental services—economic instruments to remunerate people and communities for conserving and recovering natural resources such as rainforests, water and biodiversity—which were also discussed in the assembly, were limited and seen to restrict the autonomy of fruit producers. This stance prioritizes the fight against active deforestation, leaving communities that already practise sustainable production with little or no access to payment programmes.

2.4. Lessons learned for using deliberative democracy to influence climate policy

The climate assembly design and implementation process offered several lessons. It also provided insights into the condition of the sustainable bioeconomy sector and the challenges to accessing climate finance in Bujaru.

Learning from the deliberation process

Technical experts and public servants are essential to sustaining the process. In terms of political support for the deliberation process, the climate assembly managed to generate commitment by bringing in both technical experts and public servants from municipal and state government to promote a shared agenda. This governance structure is unprecedented in a context of political party dissent and polarization. Cooperation was rooted in a shared belief in the strategic objectives of the state’s bioeconomy plan and its local implementation in Bujaru. The lesson shows that, when elected officials do not give political support to the process, the engagement of technicians and public servants can create governance agreements that sustain the assembly recommendations, which is an effective strategy to attract interest from reluctant elected officials (de Soysa 2022).

Engaging with traditional communities strengthens the legitimacy of the deliberation process. In the deliberation process, participants from traditional communities who brought diverse discursive elements, such as sounds, poetry and storytelling, were welcomed into the deliberative contributions. This connected the process with local knowledge and forms of expression, adding local understandings to strengthen the legitimacy of the assembly’s work.

Citizens can reach consensus on recommendations through deliberation. There was little dissent in the deliberation on the recommendations, even though members held differing political views. Members from different ends of the political spectrum—all agricultural producers—understood that the climate crisis affects their production equally. The connection between the remit and participants’ personal experiences made it easier to reach a consensus on the recommendations.

Being included in the assembly encouraged members to engage in local politics. The assembly encouraged different forms of political involvement at the municipal level. Some assembly members engaged with climate issues in the local elections, informed by the process in the assembly. One participant from a traditional community even expressed interest in running for office, showing that deliberative experience can encourage civic participation.

Planning the assembly allows facilitators to learn critical lessons about the potential and limits of the deliberation. As the facilitator of the assembly, Delibera Brasil learned critical lessons from the process of organizing the climate assembly through identification of the relevant stakeholders in the climate ecosystem, the capacities of the programmes and priorities. The Bujaru experience revealed how climate assemblies operate within boundaries set by larger-scale decisions: while communities and local governments can meaningfully deliberate, their capacity to act on those decisions is constrained by funding mechanisms, eligibility criteria, and priorities established through national and international climate governance processes in which they have little participation.

Lessons learned on implementing the policy recommendations

Following the recommendations, climate assembly members continued to create local initiatives, such as efforts for Bujaru to resist palm oil production and join the state-level bioeconomy plans. Some assembly members created a social media profile called Bujaru Verde, which aims to promote the municipality and strengthen family farming, tourism and forest conservation, in line with the recommendations formulated by citizens. This action shows how climate assemblies contribute to creating a sense of community ownership for citizens, which promotes innovative community-led initiatives, even without sufficient climate finance. Such dedicated initiatives foster continuing citizen engagement in local climate governance processes well beyond the climate assembly and reinforce the return in value of investing in climate assemblies and their deliberated recommendations.

Climate assemblies can draw on local knowledge to strengthen and unify the actors seeking climate finance. In terms of creating policy impact, actors, including Delibera Brasil, the Municipal Agriculture Secretariat, city council members, community cooperatives and the Pará state deputy secretariat for bioeconomy, continue seeking funding opportunities to implement the recommendations one year after the conclusion of the assembly. The existing climate finance mechanisms at the municipality are insufficient for the assembly recommendations to expand sustainable production. Paradoxically, this limitation made the actors involved more unified, cementing the narrative that Bujaru is a productive agricultural area that is ready to move forward with more ambitious economic actions. This belief is rooted in the experience and work of its communities and in its self-management skills.

Drawing on their experiences with local organizations and grassroots activism, assembly members recognized the challenges and complexities associated with payment for environmental services and government programmes, leading them to direct many recommendations towards civil society organizations. In Bujaru, this approach placed greater trust in, and reliance on, existing local organizations and activist networks, demonstrating how citizens’ assemblies can effectively decentralize power and mobilize diverse actors beyond government structures—an outcome particularly valuable in climate governance contexts, where implementation often requires broad societal engagement.

These innovations related to the quality and processes of citizen deliberation alone did not suffice to change the underlying structural conditions of the local economy. Despite sustained actions, the institutions supporting the climate assembly could not access the resources necessary for the implementation of its recommendations, highlighting the fact that climate assemblies need to operate in conducive environments for deliberating and implementing recommendations while navigating complex political dynamics to be successful. While securing implementation funding is ideal, the Bujaru case reveals an important dynamic in Amazonian territories: many communities lack financial resources but possess valuable knowledge of local needs and priorities. In these contexts, climate assemblies can serve an important function even without guaranteed implementation funding: they establish legitimate, community-defined development pathways that funding mechanisms can then adapt to support, shifting the traditional logic, where available resources shape local priorities. Instead, assemblies like Bujaru’s create a deliberative foundation that demonstrates what communities and local governments prioritize, encouraging funders to align their investments with local realities rather than imposing external priorities.

References Chapter 2

Almeida, D., ‘Brazil, France launch program to raise €1 bi for bioeconomy in 4 years’, Empresa Brasil de Comunicação, 27 March 2024, <https://agenciabrasil.ebc.com.br/en/internacional/noticia/2024-03/brazil-france-launch-program-raise-eu1-bi-bioeconomy-4-years>, accessed 1 November 2025

de Soysa, A., ‘Engaging Reluctant Duty-Bearers’, Transparency International, 31 January 2022, <https://knowledgehub.transparency.org/product/engaging-reluctant-duty-bearers-considerations-and-strategies-for-civil-society-organisations>, accessed 1 October 2025

Delibera Brasil, ‘Carta de Recomendações: Assembleia Cidadã de Bujaru BioEconomia Sustentável: caminhos e escolhas para gerar trabalho, renda e qualidade de vida em Bujaru’ [Letter of Recommendations: Bujaru Citizens’ Assembly Sustainable BioEconomy: Paths and choices for generating jobs, income and quality of life in Bujaru], 12 February 2025, <https://deliberabrasil.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/02/Carta-de-Recomendacoes-BUJARU.pdf>, accessed 1 November 2025

Spada, P. and Peixoto, T., ‘The limits of representativeness in citizens’ assemblies: A critical analysis of democratic minipublics’, Journal of Sortition, 1/1 (2025), pp. 137–159, 2025, <https://doi.org/10.53765/3050-0672.1.1.137>

Marcella Nery

3.1. Formulating the climate assembly remit for the people and context of Barcarena

The municipality of Barcarena is a mix of intertwining industrial and urban areas, home to large mining companies and the village of Vila dos Cabanos, originally designed for company employees and later occupied by other residents. The transformation of the landscape began in the 1970s and 1980s, driven by federal development policies that attracted large mining and metallurgical projects to the region. This urban-industrial area was shaped by the economic and political relations between companies, the municipal and state governments, and local communities.

Barcarena, September 2025

The combination of transnational companies and traditional populations altered the landscape immensely, displacing communities and reconfiguring local ways of life. This transformation is reflected in the social-spatial structure of a municipality with a population of almost 130,000 people, where rural and island areas form the surroundings of the industrial hub—areas where traditional activities such as fishing, family farming and the extraction of natural resources are carried out.

In 2021, Barcarena had the fifth-largest gross domestic product (GDP) in the state of Pará, at BRL 9.2 billion (USD 1.7 billion), after Parauapebas, Canaã dos Carajás and Marabá—municipalities with strong links to iron and copper mining—and Belém, whose growth is supported by the services sector. Like these municipalities, Barcarena has a concentrated economy, with the manufacturing industry accounting for almost 70 per cent of its total value. Per capita GDP stands at BRL 71,474 (USD 13,258), more than double the state average (Instituto Brasileiro de Geografia e Estatística n.d.). However, this indicator does not fully reflect local inequalities or the socio-environmental challenges posed by industrial activity. The taxes collected from these companies are the main source of municipal income, evidencing the local economy’s strong dependence on the industrial and extractive sectors.

In 2009, a waste dam overflowed and contaminated the Murucupi River, which bisects the municipality, marking a turning point in the recent history of Barcarena and triggering a series of territorial disputes and legal proceedings. The local communities, supported by the Federal Public Prosecutor’s Office (Ministério Público Federal) and the State Public Prosecutor’s Office of Pará (Ministério Público do Estado do Pará), called for reparations, accountability and a guarantee of their rights. More recently, the Cainquiama (Association of Caboclos, Indigenous and Quilombolas of the Amazon) has been representing approximately 11,000 people affected by pollution from mining activities in the region, filing a class-action lawsuit in the Netherlands against the Norwegian company Norsk Hydro in 2021. Earlier community mobilization efforts included the ADEBAR (Association of Displaced by CODEBAR), formed in 1987, which organized displaced residents and filed actions seeking compensation.

In response, companies in Barcarena and municipal authorities sought to establish new channels of dialogue and cooperation, with the aim of restoring trust and fostering local development. Against this backdrop, in 2019 a sustainable initiative called the Sustainable Barcarena Initiative (Iniciativa Barcarena Sustentável, or IBS) was launched by the company Hydro in response to the claims filed after the environmental disaster. The IBS is financed by the Hydro Sustainability Fund, established in 2019 by Norsk Hydro and its local subsidiaries—the Alunorte alumina refinery and the Albras aluminium plant, both located in Barcarena—to support sustainable development projects in the region (Hydro n.d.).

With a commitment to invest up to BRL 100 million (USD 18.5 million) over 10 years, the Fund aims to support initiatives focused on generating income and employment and on promoting the value of cultural heritage and environmental conservation, based on guidelines drafted in dialogue with civil society through the IBS. Today, the Initiative is a space for proposing and legitimizing decisions on the use of resources, strengthening the participation of local actors in setting investment priorities.

Despite institutional progress and cooperation initiatives, the development of Barcarena is still conditioned by global commodities cycles and the decisions taken by large corporations. This dynamic poses challenges for productive diversification and increasing local autonomy. To build a sustainable territorial development trajectory, local capacities must be strengthened, inequalities must be reduced, and resilience strategies must be developed to withstand economic and climate change.

Building on the partnership with the Pará State Secretariat for the Environment and Sustainability (SEMAS) established during the Bujaru assembly, Delibera Brasil worked with SEMAS to expand the climate assembly initiative to additional municipalities. SEMAS suggested Barcarena, recognizing that Amazonian municipalities experiencing advanced mining and industrialization processes represent a critical yet underrepresented profile in climate discussions and climate finance dialogues. To tackle this situation, Delibera Brasil approached the Barcarena municipal government to organize the assembly, thus presenting a strategic partnership–driven approach. The Barcarena climate assembly’s remit centred on the following questions: Which climate needs does Barcarena have and require funding for? How and under what conditions can the municipality access climate finance?

3.2. Implementing the climate assembly methodology

Participant recruitment in Barcarena employed a multipronged strategy designed to reach diverse population segments across the municipality’s geography. The Delibera Brasil team trained and supervised four local recruiters who implemented complementary approaches. Through a civic lottery, 50 census tracts were selected, and 525 invitation letters were delivered to randomly selected households within these areas. The team also established recruitment stations at high-traffic flow points throughout the municipality, while the IBS supported spontaneous online registration through its communication channels. Additionally, recruiters conducted targeted outreach in public locations to reach underrepresented profiles, particularly island inhabitants and members of rural communities who were less likely to receive letters or access online registration. The recruitment process yielded 195 registrations for the sortition, corresponding to an acceptance rate of 37 per cent of those who had received invitation letters, along with 43 spontaneous online registrations. The stratification process considered multiple dimensions to ensure representativeness, including gender, education level, age, occupation, race and ethnicity, geographic location, and connection to the IBS network.

However, recruitment faced challenges that required adaptive strategies. For example, more women than men registered across all areas, a pattern particularly pronounced in industrial zones, where men often worked rotating shifts in the aluminium and other mining facilities, limiting their ability to participate. Certain sectors, especially the industrial area, exhibited lower overall response rates despite multiple contact attempts. To address these imbalances, Delibera Brasil adapted their approach in the final days of recruitment. When households declined to participate, recruiters were instructed to approach neighbouring houses, using surplus invitation letters, effectively expanding the reach beyond the initially selected addresses. The team also conducted targeted street-based recruitment focused specifically on male residents, using spare letters to register more men and improve the gender balance of the final participant pool.

Barcarena, September 2025

The climate assembly took place over four weekends, with each session focusing on different aspects: (a) exploring the deliberative process and citizens’ aspirations regarding the future of the Amazon region and Barcarena, with the chief of staff of the Vice Mayor of Barcarena in attendance; (b) engaging with representatives from the municipal secretaries’ offices who presented projects from the Pluriannual Plan (PPA), the municipality’s mandatory four-year strategic planning and budgeting document that outlines all public investments and programmes (discussions focused on PPA initiatives related to climate finance, environmental management and sustainable development, providing citizens with context about existing institutional priorities in these areas); (c) discussing with the IBS and community leaders their experiences of financing mechanisms and raising funds and drawing up recommendations in subgroups; and (d) deliberating on final recommendations and identifying two central questions as an outcome of the discussions—the assembly’s position on international financing sources and the viability of setting up a municipal climate fund.

3.3. Pathways for implementing the climate assembly recommendations

The participants sorted their 10 recommendations into 3 complementary sections. The first section contained large infrastructure projects, such as drainage and coastal protection, which require specific planning and resources. The second encompassed sustainable agriculture and bioeconomic initiatives, aimed at decentralizing production, preserving the environment and generating income. The third focused on governance, proposing a climate finance committee and a municipal fund on climate change and sustainable development. The climate finance committee would include representatives from municipal government, city council, civil society organizations, industry, traditional and quilombola communities, universities and climate assembly delegates. The committee would assess the fund’s viability, identify funding opportunities and develop a climate finance plan for 2026–2029.

The municipal fund would be financed through environmental fines, compensation for greenhouse gas–emitting activities, contributions from other environmental funds, and national and international donations and loans. This governance structure would ensure that citizens and civil society can actively participate in allocating and monitoring climate finance. These recommendations reflect the participants’ emphasis on long-term solutions that build upon existing community experiences, demonstrating how local, municipal and regional actions can be integrated into a comprehensive climate agenda. A formal letter containing these recommendations will be delivered to city hall representatives in November 2025, one week before the COP30 summit in Belém.

Barcarena, September 2025

The climate assembly brought together municipal secretaries who had previously worked in isolation on climate finance issues. During the preliminary planning stages, the Delibera Brasil team coordinated discussions with municipal authorities that highlighted the need for a unified approach. Delibera Brasil facilitated the formation of a cross-departmental task force among the secretaries to engage with the assembly process. Working collaboratively, they collectively analysed municipal PPA actions, developing a comprehensive understanding of the municipality’s climate challenges. This exercise revealed structural gaps, particularly the absence of a dedicated body for integrated climate management and fragmented initiatives that lacked a coherent strategic territorial vision for climate change.

In a parallel effort, Delibera Brasil encouraged the IBS network to convene and articulate their vision to the climate assembly. This request prompted IBS members to identify common ground and showcase community-based initiatives that reflected their collective aspirations for the municipality’s future. By bringing both government secretaries and civil society networks into structured dialogue, Delibera Brasil created a deliberative space where these parallel mobilization efforts could converge. By the end of the process, the secretary for agriculture expressed interest in leading an integrated effort to raise climate funds, signalling a shift towards sustained interdepartmental collaboration. This dual coordination—mobilizing both government and civil society to prepare for the assembly—ensured that the climate assembly recommendations reflected both institutional capacity and community priorities, creating a robust foundation for climate action in Barcarena.

3.4. Lessons learned

Climate financing requires imagination. The climate assembly process highlighted a challenge affecting both civil society and government, particularly the need for a long-term strategic vision for climate finance. During the deliberations, participants observed that existing funding patterns had shaped expectations about what climate finance could achieve in Barcarena. The IBS network, for instance, had primarily supported communities to access small grants from the Hydro Fund, which, while valuable, created a pattern of thinking focused on short project cycles and modest budgets.

The assembly’s structured dialogue revealed how this limitation reflected similar constraints in the public sector, where municipal climate planning operated within four-year electoral cycles with secretaries working separately. When participants examined the municipal PPA alongside community initiatives, they noted that neither small-scale community projects nor fragmented municipal programmes addressed the long-term climate action Barcarena needed. This observation led participants to recommend the creation of a climate finance committee and a strategic plan extending beyond electoral cycles. By bringing diverse actors together to review both community and institutional approaches, the deliberative process encouraged participants to reconsider assumptions about the scale of and timeframe for possible climate action in Barcarena, pointing towards more ambitious, integrated and sustained climate financing strategies.

Non-financial conditions can be used as a viability criterion to unlock climate finance. The assembly drew attention to the potential use of non-financial conditions as a criterion for unlocking climate finance proposals. This insight emerged during discussions about water access projects, when participants recognized that different types of initiatives required various financing strategies and accountability mechanisms. As such, the assembly examined complementary water proposals—a municipal project for deep wells and irrigation and a community-based rainwater harvesting initiative for potable water. While these initiatives would pursue different funding sources and follow different timelines, the essential nature of water access—particularly for vulnerable communities in island areas—led participants to propose non-financial conditions for monitoring and governance by the beneficiary communities themselves as a guarantee that investments would be permanently maintained.

Participants suggested community-based accountability mechanisms such as rotational management systems, where residents take turns overseeing infrastructure maintenance. This approach addresses a fundamental challenge: local communities frequently lack the formal institutional capacity to meet traditional finance providers’ requirements. By recognizing consolidated local governance arrangements—such as community participation, established public oversight structures and co-accountability in resource management—financing bodies could broaden their assessment criteria beyond conventional financial guarantees. The assembly extended this logic to other projects, recommending that sanitation and waste management initiatives include non-financial conditions supporting existing recycling cooperatives, and that proposals for locality-specific projects demonstrate prior community dialogue and documented consensus as a precondition for pursuing financing. These non-financial conditions serve dual purposes: they provide funders with assurance of long-term project viability while respecting community autonomy and building local ownership.

Combining the efforts of the state and civil society can create more strategic approaches to climate finance. The assembly revealed contrasting views among participants regarding the capacities of the state and civil society to execute climate projects. Civil society initiatives are recognized for their precision and local knowledge, while state-led projects often face bureaucratic delays and slower responsiveness to local needs. The sessions demonstrated that these actors currently often compete for the same limited funding sources rather than collaborating. Participants concluded that this competitive dynamic undermines the climate agenda’s potential and proposed that a more strategic approach could leverage the distinct capacities of each actor. Using water projects as an example, participants identified complementary proposals requiring different financing strategies: the municipal government’s deep wells and irrigation project would pursue medium-term concessional loans, primarily from Banco da Amazônia, while the community-based rainwater harvesting system would seek short-term grants or private social investment from regional companies. This approach combines civil society’s capacity for community engagement with the institutional continuity and formal legitimacy of public authorities, converting operational differences into coordinated advantages that broaden the effectiveness of climate action.

Communities face a structural dependency on private social investment. Private social investment is the main source of community climate finance in Barcarena.5 Environmental compensation funds for industrial damages and taxes from industrial activity are sent to the state government rather than being directed towards reparations in the territories where the damage occurred, creating a structural disconnect where municipalities bear the environmental and social impacts while receiving limited direct benefits. Community-led climate actions—such as restoring degraded areas, protecting water sources and strengthening local food systems—generate meaningful socio-environmental benefits for those directly affected. However, compensation mechanisms channel resources away from impacted communities, with the Hydro Fund emerging as one of the few accessible funding sources for local climate projects. This creates a paradox: communities must rely on extractive industries’ social investment to implement climate projects, effectively depending on the very actors whose operations threaten their territories and environmental security. While alternative climate finance sources exist—including international climate funds, multilateral development banks, blended finance mechanisms and environmental services programmes—these resources remain inaccessible to local communities and municipal governments due to complex application processes, technical requirements and institutional frameworks designed for global entities.

References Chapter 3

Hydro, ‘Sustainable Barcarena Initiative and community investments’, [n.d.], <https://www.hydro.com/en/global/media/on-the-agenda/the-alunorte-situation/our-commitments/sustainable-barcarena-initiative-and-community-investments/>, accessed 1 November 2025

Instituto Brasileiro de Geografia e Estatística, Cidades e Estados [Cities and States], [n.d.], <https://www.ibge.gov.br/cidades-e-estados/pa/barcarena.html>, accessed 1 November 2025

Marcella Nery

4.1. Formulating the climate assembly remit for Magalhães Barata and its citizens

‘If you look at the map, our municipality is criss-crossed by bodies of water. Everywhere you look in Magalhães Barata, there is a spring.’ This observation, made by a participant during a session of the climate assembly in Magalhães Barata, highlights the importance of water in the municipality’s physical and symbolic landscape. Known as the ‘City of Streams’, Magalhães Barata is home to 158 perennial springs and the Marapanim River, which flows through the whole municipal area. Known as a nursery for Amazonian species, the river plays an essential role for both environmental conservation and local food and economic security. The presence of river and many other water sources in such a small area makes the municipality a strategic spot for discussions on climate governance and the preservation of aquatic and Amazonian ecosystems.

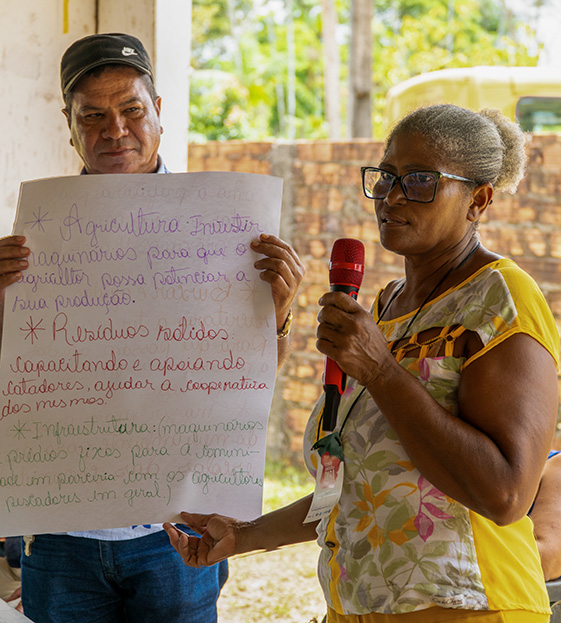

Magalhães Barata, September 2025

Like other municipalities in the coastal part of north-east Pará, Magalhães Barata has undergone many far-reaching changes, which have turned it into the river–floodplain–rainforest landscape it is today. The current administrative district, which has a population of nearly 8,000 people, was formed following the unification of centuries-old villages. The municipality comprises 17 ecological villages, 6 of which are located within the boundaries of the Cuinarana Marine Extractive Reserve.6 This territorial configuration means that a significant portion of the population lives under a specific conservation and resource management framework that shapes both their livelihoods and their relationship with the environment.

The Cuinarana Marine Extractive Reserve was inaugurated by federal decree in 2014 to preserve the biodiversity of mangroves, sandbanks, dunes, floodplains, flooded fields, rivers, estuaries and river islands, as well as to protect traditional ways of life. Since they live on an extractive reserve, community members hold the right to sustainably harvest natural resources—primarily through fishing and selective extraction—while maintaining collective land use under federal protection. In return, residents must follow sustainable management practices, participate in collective governance through community associations and refrain from activities that degrade the ecosystem, such as industrial fishing or deforestation. This framework creates a protected area that combines conservation with the continuation of traditional livelihoods. The main socio-economic activity is traditional fishing, which guarantees income and food security for most of the population. Fishing, knowledge of which has been passed down orally from generation to generation, is both an economic activity and a building block of the community’s collective identity.

The municipality is also host to Coastal 500, a global network of local leaders from developing countries committed to sustainable governance for traditional fishing and the prosperity of coastal communities. The growing pressure on water and fishing resources motivated Magalhães Barata to apply for the Delibera Brasil Call for Proposals in 2023 to convene a climate assembly, at the initiative of the municipal secretary for the environment.

The Delibera Brasil team convened a diverse group of local actors to determine the climate assembly’s remit, including the Magalhães Barata Producers’ Association, the Rural Workers’ Union, the Municipal Council for Environmental Defence, the president and members of the Cuinarana Marine Extractive Reserve, social workers and community health agents. Through this collaborative process, the assembly’s remit was formulated to address the municipality’s most pressing challenges, centring on the following question: How can climate finance help Magalhães Barata generate income for the local population, protect its waterways, develop sustainable tourism and address the impacts of climate change? This focus highlights the importance of prioritizing small towns with extractive reserves and strategic water basins in discussions on climate finance in the Amazonian region.

4.2. Implementing the climate assembly methodology

The assembly took place over two weekends in September 2025 and was attended by 30 randomly selected participants representing a diversity of ages, gender, educational level, community ties and territorial locations. The sessions took place two months before the COP30 summit, to be hosted in Belém, 160 kilometres away, which connected the local deliberations with the global climate agenda.

Recruitment was organized by the Delibera Brasil team, which trained six local recruiters to conduct door-to-door outreach over 10 days. This method was necessary because the local villages use a variety of address systems: most lack street names or house numbers, making it impossible to send invitation letters to registered addresses, as was done in Bujaru. The recruitment methodology was designed to ensure that at least 5 per cent of Magalhães Barata’s population would be invited to register for the random selection.

Magalhães Barata, September 2025

To achieve geographic representativeness, recruiters were distributed across the municipality’s distinct territorial zones: extractive reserves (wetlands with mangrove trees and saltwater) and dry areas (freshwater rivers, streams and agricultural zones). Recruiters walked through the villages following a protocol: they would knock on the first house, and if the household accepted the invitation, they would skip four houses and knock on the fifth. If the first house declined, the recruiter would proceed sequentially to the next house without skipping until an invitation was accepted, and would then resume the pattern of skipping the next four houses. This approach supported randomization while adapting to the village infrastructure, ensuring that recruitment remained representative despite the absence of formal addresses. Of the 379 people invited to participate in the random selection, 357 agreed to take part, resulting in a response rate of 94 per cent.

Although archaeological evidence and oral history suggest links between existing communities and Indigenous and quilombola populations in the past, Magalhães Barata does not have any formally recognized Indigenous or quilombola communities. This lack of recognition reflects a broader challenge across Amazonian territories, where stigma associated with certain community identities can prevent groups from seeking formal recognition, even when they would be eligible to do so under national frameworks for traditional communities. However, the six villages within the boundaries of the extractive reserve are home to populations recognized as traditional fishing communities, whose rights and livelihoods are protected under the extractive reserve framework. No special treatment was given to these six communities during recruitment, as the number of refusals was low, and the door-to-door process across all villages already ensured proportional numerical representation of their inhabitants in the final sample.