Democracy in a time of crisis

Democracy in a time of crisis

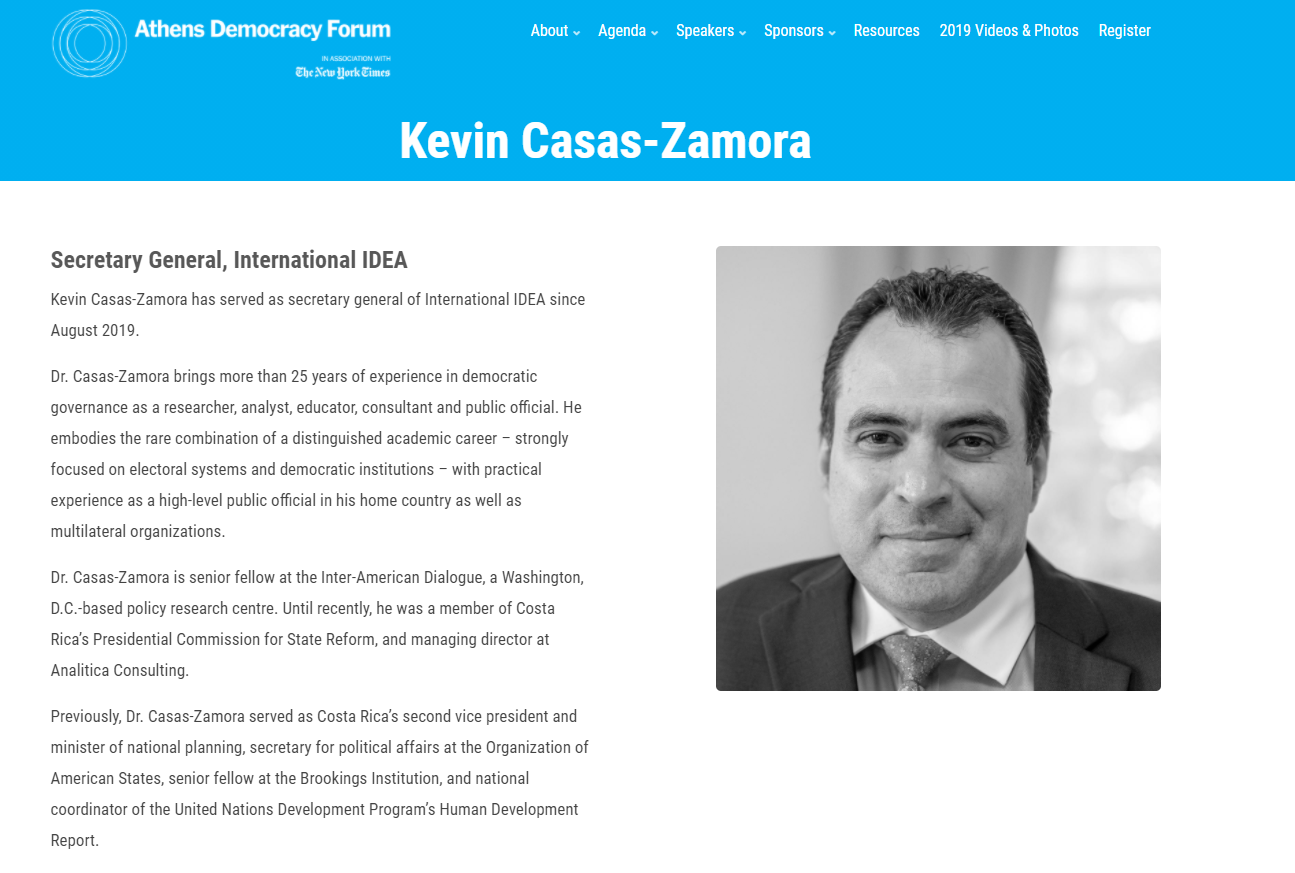

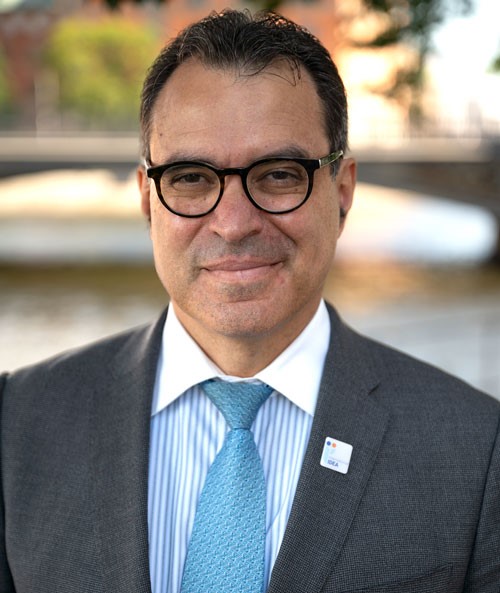

Dr Kevin Casas-Zamora

Secretary-General, International IDEA

Good morning.

I would like to thank the Athens Democracy Forum and the New York Times for the kind invitation to be here. For International IDEA is a joy and an honor.

I have little time and hence will just make three points related, in different ways, to the resilience of democracies in times of crisis.

My first point is about the need to make democracies more resistant to calamities, such as the current one. For that to happen, we must make democracies better at managing uncertainty. One of the concerns that many of us have in the current context is that the use of emergency powers, which have been invoked all over the place, becomes par for the course in democratic systems. But here I would like to introduce a nuance – the real risk is that emergency measures become par for the course, not simply because authoritarian leaders demand them, but because fearful citizens tolerate them. In times of enormous uncertainty, the longing for the “paternal” embrace of authoritarian leaders can be a powerful impulse. It is not coincidental that the global advance of democracy in the past half a century coincided with the ability of societies to reduce dramatically some of the most acute sources of human anxiety – violence, poverty, and disease. The odds for the survival of democracy are much better when it proves able to lower social uncertainty to manageable levels. That’s why robust welfare states, solid rule of law, and sustained fiscal prudence are so critical – they reduce uncertainty.

My second point is about a political lesson that has clearly emerged from this predicament. The response to the pandemic is not a contest between democracies and authoritarian systems. The relevant question is a different one, and it goes back to the insight once expressed by the late Samuel Huntington – in this situation, the type of government a country has matters less than the degree of government it possesses, i.e. the capacity of its institutions to act effectively. There are authoritarian systems with high state capacity (China, Singapore), and with pitifully low capacity (Venezuela), just as there are democracies with high state capacity (South Korea, Germany) and those with low levels of it (most of Latin America). That’s the political cleavage that counts. A crucial implication flows– rather than choosing the suffocating embrace of authoritarianism, we should prioritize the measures that equip political systems and institutions to be more effective at providing public goods and services, managing uncertainty, and dealing with crises. This means paying attention to institutional designs that facilitate decision making, policy implementation, and inter-agency coordination; paying attention to the capacity of states to extract revenues and preserve fiscal health; paying attention to the quality of public management; and paying attention to the ability of institutions to elicit trust from citizens. It is not about giving up on fundamental freedoms, but about endowing democracies with the capacity to deliver.

My third point is about the social contract. This pandemic has been unforgiving in revealing the deep fault lines that are pulling societies apart. If they are to stave off the dangers of populism and authoritarianism, many democracies will have to return to the drawing board and renegotiate the social contract, the distribution of burdens between social groups, and the relationship between societies, states and markets. In Latin America, which exhibits the world’s worst income inequality levels, there is increasing talk of imposing wealth taxes, to ensure that paying for the coronavirus impacts does not fall mostly on the poor. Everywhere there is greater recognition of the dire price that societies pay for underproviding public goods, particularly healthcare.

One could only hope that the sheer magnitude of this crisis will result in many new constitutional settlements, new fiscal pacts, and new social covenants of the kind that frequently emerges in post-conflict and post-authoritarian contexts. If that happens, this crisis could pave the way for more inclusive societies, fairer economic structures, and more democratic political systems. It is not an unfounded hope. History has shown that progress often follows breaking points. This is what happened during the democratic transition in Spain, where the 1977 Moncloa Pacts forged a lasting political covenant. This is also what happened in Western Europe, where a new social democratic consensus, robust welfare states and a consolidating union emerged from the ashes of the Second World War.

The alternative to this kind of dialogue is violence, political instability, and authoritarianism. In other words, darkness. And this is exactly what happened in many countries during and after the Great Depression.

Thus, both outcomes have historical precedents, and almost certainly we’ll see them emerge in the next few years. It is incumbent on all of us that work to advance democracy to do everything within our reach –from speaking up to facilitating knowledge—to help countries go down the route of dialogue towards a better social, economic and political equilibrium.

There are not many silver linings in this catastrophe. This opportunity for democratic renewal is one. We should grab it with both hands.

Thank you.