Women leading the struggle for democracy and a new social contract in Iran

Protests in Iran, sparked by the arrest and killing of Mahsa Amini at the hands of Iran’s “morality police,” resulting in a global wave of solidarity, have provoked an outpouring of deep-seated and far-reaching public grievances related to poor governance, economic decline, social disparities, endemic corruption and lack of transparency and accountability. With their lives at stake, citizens from every segment of society—including university students, children, and school pupils, and even workers from the vital oil sector—have poured into the streets. The broad-based support for protesters and the multiplicity of demands points to the public’s demand for the renegotiation of a social contract.

But what should Iran’s new social contract look like? At its core, a social contract is an agreement between the people and their sovereign on rights and obligations toward each other. In the immediate aftermath of the 1979 Islamic Revolution that overthrew a half-century of secular dictatorial rule, Iran’s incoming leaders established a post-revolutionary social contract promising freedom to all and social welfare for the underprivileged. The Revolution, however, brought a new dictatorship to power – a theocratic regime that still rules today and controls most aspects of society. The Iranian covenant is unraveling. The government has failed to deliver on its promise of a virtuous, prosperous, and free Islamic society; it has instead been marred by the state’s clerical despotism, economic mismanagement, corruption, and gender apartheid

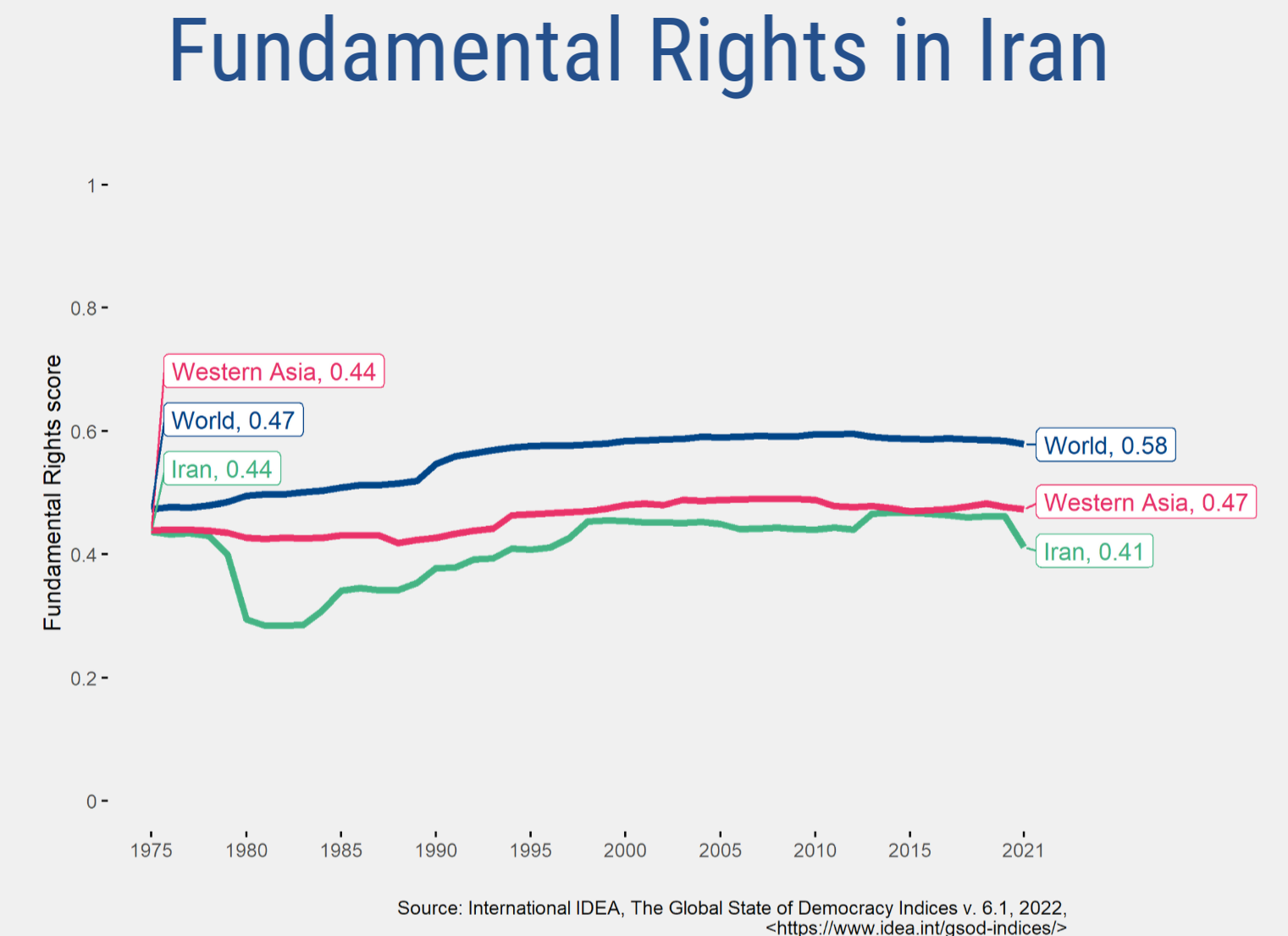

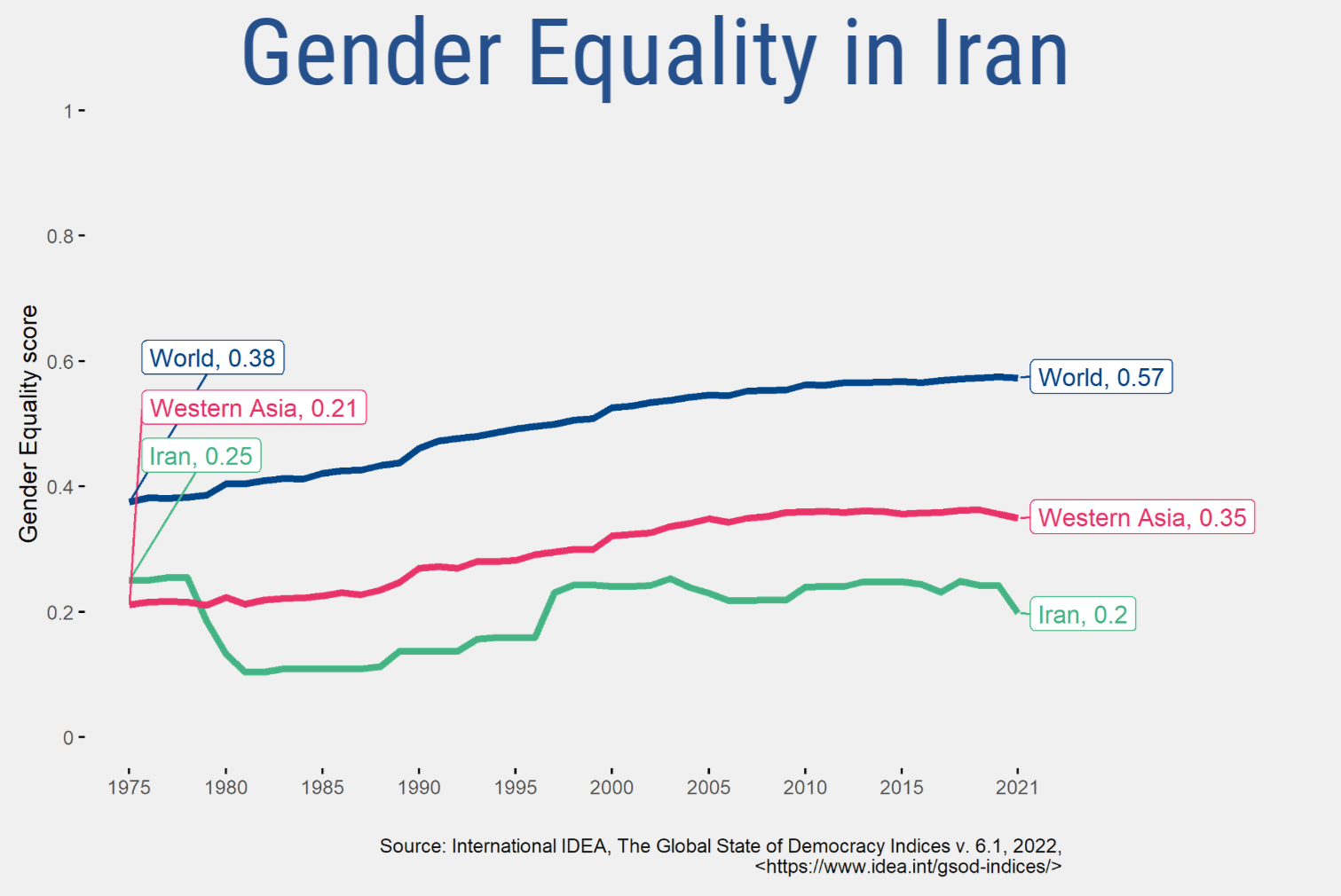

Women and men in Iran want to live more freely, and a government that is at peace with the world and prioritizes the welfare of its citizens. A new social contract should stipulate rights to gender equality, improved living conditions, and social liberty for Iranians. The Global State of Democracy Indices (GsoDI) show Iran's performance on Fundamental Rights is poor, well below global and regional averages, with a steep decline observed after the 1979 revolution. The sub-attribute of Gender Equality performs particularly poorly.

Today’s unrest is also rooted in a legitimacy crisis facing Iran’s leadership. Electoral turnout has traditionally been very high, suggesting faith and support in Iran’s government. But the GsoDI show a steep decline in Electoral Participation in the last two years, suggesting widespread public disillusionment which has been attributed to the country’s economic situation and is a threat to the legitimacy of theocratic rule.

Economic despair has also eroded the social contract. the World Bank estimates that 40 per cent of the country lives below the poverty line as a result of severe economic decline. Years of sanctions have excluded Iran from the global financial system, leaving the country unable to gain from oil wealth. The economy has further deteriorated due to corruption and mismanagement of state resources by the government. Legitimacy challenges have been posed by high inflation, depreciated currency, soaring prices and high unemployment, deepening disillusionment over the regime’s failure to improve the economic and living situations in the country.

The current uprisings reveal broad frustration over unmet social and economic needs. Iranians have lost faith in the government’s ability to deliver reforms, and they have shifted their aspirations of reform to goals of revolution. While it is too early to predict, failing to address the protestors’ demands will encourage further dissent that could trigger the eventual downfall of Iran’s clerical regime. With international support for protestors putting further pressure on the Iranian government, coupled with the 82-year-old supreme leader’s ailing health, prospects for democracy in Iran could look cautiously optimistic over the long term. It remains to be seen whether the protest movement will be strong enough this time to destabilize the regime and represent the disruptive and revolutionary route required for successful democratization in Iran without resorting to violence and in a pacifist climate favoring peacebuilding and multi-stakeholders consultation and negotiation.