Online Voting

Current and Future Practices

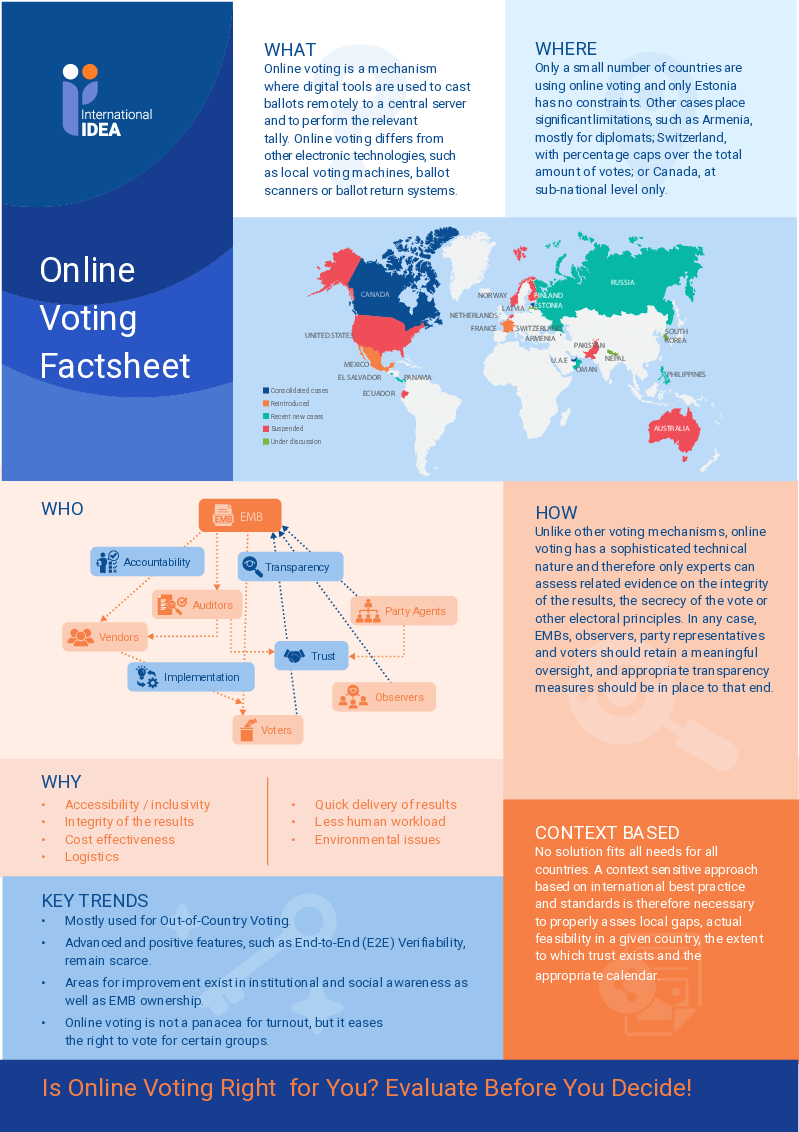

In recent decades, in parallel with the development of Internet services, online voting has gained prominence as an innovative channel that could address recurrent election gaps in terms of accuracy, accessibility or fraud, among other things. While its advantages seem very apparent, there are also risks, and the balance among early implementors was inconclusive. Successful cases from both democratic and less-democratic countries have been recorded together with important failures, for a wide range of reasons often unrelated to technical problems. Other factors have had an important role, such as the legal framework, the level of electoral management body (EMB) in-house expertise, time pressures and voter education.

In 2025, online voting can no longer be regarded as a new technical solution. There are already countries with a consolidated practice, others with recent implementations and the technology as such has also evolved, with important updates. There was a certain pause among pioneering countries, such as France and Switzerland, which put this technology on hold, but the situation changed once the Covid-19 pandemic was over. While certain past users resumed online voting operations, other new players, with an important role for Latin American countries, decided to test the technology to address out-of-country voters in particular. Finally, attention should be paid to developments in authoritarian regimes where online voting is gaining traction.

This review of different cases identifies some indicators that could serve as key areas for successful deployment. In general terms, attention should be paid to three layers of analysis—institutional, technological and civic.

Despite the technical nature of online voting initiatives, institutional factors must be considered at a very early stage, since they will condition the entire project and become triggers of failure or success. In this regard, online voting needs a context-based approach so that general patterns are duly tailored to local scenarios. Clear ideas on the electoral gaps to be resolved and feasibility studies to identify constraints will be crucial. Assessing the in-house expertise of the EMB, together with the legal framework and how crisis scenarios are handled, could provide an initial understanding of where the constraints might be in a given country, and the project could be adjusted accordingly.

Second, operational considerations will determine key aspects of development and implementation of online voting projects. Beyond the phases that exist in any computer-based initiative, such as the technical design, compliance or logistics and training issues, other aspects need attention since online voting will be used in parallel with other remote or in-person voting channels. Timing, for instance, is crucial as online voting is normally seen as an advance voting mechanism. Compatibility with other channels and the relevant regulations in terms of voter registration/authentication will be important to prevent double voting or similar fraud. Finally, the election cycle in general reflects the complex procedures in which online voting is supposed to be embedded, and provides guidance on reasonable timelines for its successful implementation.

Third, there are civic dimensions related to trust building and how to compensate for the limits on transparency that any online voting system involves for election stakeholders and laypeople in general. Individual and universal verifiability procedures have been developed to address such concerns, but complementary auditing and certification safeguards would also be required to cover all the necessary angles. How to design such controls in terms of their scope, auditors’ eligibility or, among other items, the extent to which findings and conclusions are disclosed could determine the impact on the confidence accorded to an online voting system.

Online voting brings a set of very clear advantages for electoral processes but at the same time raises important concerns, as it alters how key principles, such as the secrecy of the ballot or the integrity of results, are ensured, and how trust is built for all stakeholders and laypeople. There are no easy answers. Each country needs to assess whether the benefits will be important enough to accept the risks and, based on such conclusions, take all the measures necessary to implement a robust and trustworthy online voting system. Local expertise in the EMB and among stakeholders, coupled with sufficient time to unfold all the preparatory phases, will be crucial.

Online voting is not new. Various countries have been using it in recent decades, together with voting machines, to consolidate new mechanisms intended to improve elections in terms of accessibility, accuracy or efficiency, among other things. However, these initiatives have encountered multiple barriers and questions over the capability of online voting to ensure the integrity of elections. Such doubts have led some countries, such as France and Switzerland, to establish a moratorium or, like the Netherlands and Norway, simply dismiss use of the Internet to cast ballots. Meanwhile, public debates and related academic research have continued to try to shed light on the different aspects of online voting procedures.

Since the Covid-19 pandemic, new countries and old users have decided to reconsider, generally in a positive way, whether to use online voting, mainly for their diaspora. This report seeks to understand the prevalent patterns of this new interest. It gathers information from 22 countries, drawing conclusions that could be useful for practitioners and countries that have online voting in mind and addressing particular areas for improvement.

First, 22 brief country cases provide an overview of different approaches to the use of online voting. The study includes practices of less-democratic countries because it aims to capture all online voting experiences to date. Second, the advantages and disadvantages of this technology are discussed, together with a comparison with other special voting arrangements. The report then draws conclusions from the country cases, highlighting the main aspects to assess when implementing online voting.

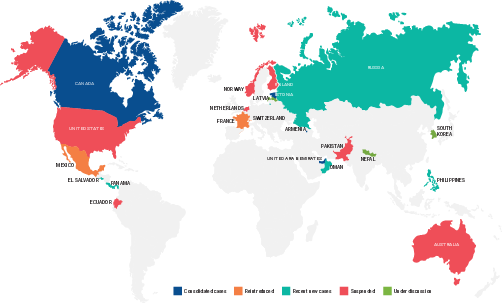

| Consolidated cases | Reintroduced | Recent new cases |

1. Armenia 2. Canada 3. Estonia 4. United Arab Emirates | 5. France 6. Mexico 7. Switzerland | 8. El Salvador 9. Oman 10. Panama 11. The Philippines 12. Russia |

| Suspended | Under discussion | |

13. Australia 14. Ecuador 15. Finland 16. The Netherlands 17. Norway 18. Pakistan 19. United States | 20. Latvia 21. Nepal 22. South Korea |

Information is provided below about how 22 countries have approached online voting. Together with some basic facts on each case, the text highlights specific features that could be useful for a compiled analysis of the main trends in the current implementation of online voting channels. The case studies are not intended to provide a full overview of each country, only initial information and the strategic data on general online voting trends. Nor is the text intended to list all online voting initiatives, only the most prominent ones (see online voting survey in 2011, EAC 2011).

1.1. Consolidated cases

Armenia

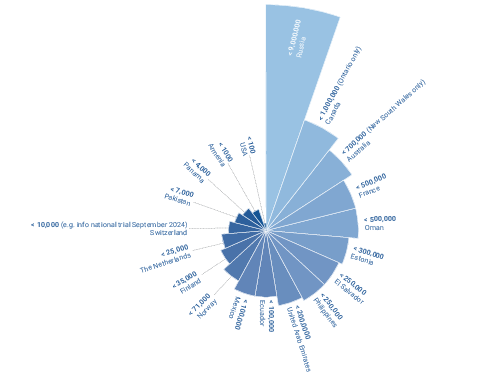

Armenia has one of the longest and least known histories of online voting, which was launched in 2012. Despite its large diaspora, its system allows only a limited pool of citizens abroad to cast ballots online. For instance, only 195 online votes were cast in 2012, 228 in 2013, 245 in 2015, 747 in 2017, 504 in 2018 and 500 in 2021 (Manougian 2020; CEC Armenia 2021). Diplomats, their families or military personnel abroad are eligible.

General out-of-country voting (OCV) was available for all expatriates between 1996 and 2005 (Manougian 2020). Voters could cast their ballot at pre-designated embassies. This system was discontinued in 2005 and OCV resumed in 2012 with an Internet voting platform, targeted at a small group of overseas voters. The system was developed in-house and, due to its limited scope, is seen as having almost no impact on election results. According to the national electoral management body (EMB), ISO certifications were in place at the beginning, but they were discontinued. Additionally, the EMB is supposed to share the source code to all stakeholders, such as political parties, should they wish to monitor the process.

Canada

Canada is another longstanding user of online voting, but the scope differs from that of Armenia. It is not used in the federal elections and provincial/territorial experience is limited, but growing. For example, it was used in the Northwest Territories for absentee voters in 2019 and 2023 and in Prince Edward Island for a non-binding plebiscite. However, Canada has a rich local tradition of municipalities, mainly in Ontario and Nova Scotia, relying on online voting systems (Elections Canada n.d.; Goodman et al. 2024). Online voting was available in Ontario in 2018 for 2.74 million (3.8 million in 2022; see Goodman et al. 2023: 89) voters, and estimates indicate that between 500,000 and 1 million voters cast their ballots online (Cardillo, Akinyokun and Essex 2019: 12). Similarly, more than 80 First Nations together with Metis and Inuit communities used online voting for various votes (First Nations Digital Democracy n.d.; Gabel and Goodman 2021: 9). Given the geographical constraints that exist in Canada, online voting is seen as the most appropriate solution (Goodman et al. 2025). Nova Scotia (Elections Nova Scotia 2024: 17) is planning to enable military personnel abroad to vote online for provincial elections in 2025.

The impact on turnout depends on whether other convenience voting systems are in place, since online voting ‘can increase turnout by 3.5 percentage points, with larger increases [of 7 percentage points] when vote by mail (VBM) is not yet required, and greater use when registration is not required’ (Goodman and Stokes 2018: 1155, 1157).

At the federal level, a commission was created in 2016 to study the possibility of using online voting in national elections. It recommended not to implement it at that time (ERRE 2016: 116). In 2020, a federal election committee assessed how to facilitate voting operations during the pandemic. However, it found that ‘implementing [Internet voting] would require significant planning and testing in order to ensure that the agency preserves certain aspects of the vote, including confidentiality, secrecy, reliability and integrity. Given the current operational and time constraints, this option cannot be explored properly at this time’ (Harris 2020). The distinction between municipal and federal approaches in Canada likely relies on different conclusions when risk assessments are conducted, which could provide guidance tor other countries.

Estonia

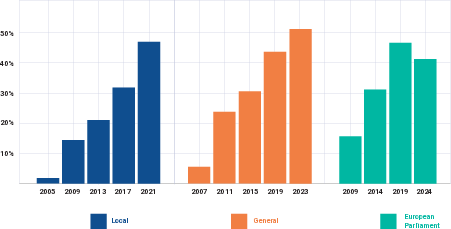

Estonia has been using online voting since 2005. It is the only country thus far where it is available with no limitations, that is, implemented nationwide and for any election (Valimised n.d.d). All other countries put some restrictions in place when using online voting, often limiting its scope to certain voters or specific types of elections.

Estonia considers online voting to be an additional aspect of its digital national strategy to enhance all kinds of electronic services as a way to keep public administration and the private sector up to date. Online voting is not therefore a specific project launched by the electoral authorities alone, but a component of a broader approach. In terms of voter registration and authentication, for instance, such a concerted vision is crucial since online voting uses the same well-established identification systems available for other services.

Online voting is implemented together with other voting arrangements, such as traditional in-person voting, leaving it up to voters to decide which is more convenient for them. Online voting is also seen as an advance system to be used ahead of election day.

Its continuous track record since 2005 makes Estonia a good case for testing certain assumptions, such as cost savings (Solvak 2021a) or impact on turnout (Solvak 2021b). Studies on the former, despite challenging methodological issues, reinforce the idea that online voting is cost-effective (Krimmer et al. 2018). On turnout, however, online voting does not seem to mobilize new voters, even among young voters who might be more interested in new technologies. Absenteeism seems likely to have deeper sociological roots but online voting has proved to be a trustworthy channel in that people who use it rarely go back to using ballot papers.

Finally, specific voting functionalities make the Estonia example very useful for other countries. There are options for revoting (Valimised n.d.e), either online or on paper, to address concerns related to the secrecy of the vote and verification procedures, both individual and universal, to ensure transparency and oversight. Both revoting and verification reflect a system intended to address online voting areas of concern using advanced technological adjustments.

United Arab Emirates

Regarding the Federal National Council, voting machines were used in 2006 (UAE 2024a). Online voting systems have been in place since 2011, but ballots were cast in supervised in-person environments only (Scytl 2011). This combination of remote channels in traditional polling stations made voter authentication straightforward. As an additional component of the digital project, voters had to authenticate themselves using biometric identification (ID) services (UAE 2024b; UAE ICP 2015).

Following various electoral cycles with this system, the procedure was upgraded to allow online voting from anywhere (Morgan 2023; The National 2023). Elections in 2023 were the first to use such extended functionalities. Interestingly, ‘the smart voting system—or remote voting system—allows voters to cast their ballots in the UAE and abroad through the dedicated election application, available from the Apple App Store and Google Play’ (UAE 2023). In terms of citizen engagement, there was a rapid increase in the voters’ list from 6,595 in 2006 to 224,228 in 2015, 337,738 in 2019 and 398,879 in 2023. General turnout was 27 per cent in 2011, 35.29 in 2015, 34.81 in 2019 and 43.99 in 2023, including 5,402 ballots from abroad (Al Amir 2023; UAE 2006, 2015, 2019).

1.2. Suspended or reintroduced

France

France has long experience of using voting machines (Anziani and Lefèvre 2014), both old mechanical and modern electronic ones. However, online voting is only used for overseas voters (France Diplomatie 2024a), and for parliamentary or consulaire elections. As a matter of principle, all voters for a particular constituency, including the ones for expatriates, must be allowed to use the same range of voting channels. Online voting is an advance channel used some days ahead of election day, together with other special arrangements such as proxy voting or postal procedures. Voter authentication is undertaken by two codes sent by email and SMS, once the ID number and email address of a registered citizen abroad has been provided. In the 2014 consulaire elections, 43.21 per cent of the vote was cast online (Dandoy and Kernalegenn 2021: 434). There were different patterns of voting depending on the country in which the voter was based; in large, developed countries and in Europe there was a higher online voting turnout, than ‘in districts with a small French community with geographical and historical proximity with France and characterized by high party competition’, where ballot boxes were more used (Dandoy and Kernalegenn 2021: 434).

After a moratorium to re-evaluate the system in 2017, due to the high risk of cyberattacks (Le Monde 2017; JORF 2017), online voting resumed for consular elections in 2021 (France Diplomatie 2021) and was fully implemented for the 2022 parliamentary election (France Consul@ire 2022), which had to be partially repeated due to issues related to online voting (Constitutional Council decisions 2022-5813/5814 AN, 2022-5773 AN and 2022-5760 AN). The Ministry of Foreign Affairs leads the project together with other agencies, such as the data protection and digital environment (CNIL) or cybersecurity (ANSII) agencies (France Diplomatie 2024b). Certain verifiability features were in place allowing invited third parties for a recalculation of the results. Individual checks were also available based on receipts acknowledging that the relevant ballot had been stored into the ballot box (Cortier et al. 2023).

The second round of the parliamentary elections in 2024 registered 459,539 online votes (416,601 in the first round), which represents 77.65 per cent of the ballots cast from the relevant constituencies (72.58 per cent in the first round) and 29.37 per cent of the turnout (26.53 per cent in the first round) (MEAE 2024a, 2024b).

Mexico

As a federal state, Mexico has launched different subnational initiatives using voting machines. Coahuila in 2005 (Arredondo Sibaja 2012: 245) was the first to implement one with binding effects. In 2012, online voting was used for overseas voters from the capital city and Chiapas state (IEPCC 2012: 91–98). Further cases were implemented in Baja California Sur (Radar Politico 2015) and again in Chiapas in 2015 (IEPCC 2016: 99–104). The latter experienced serious problems linked to voter registration issues (Muñoz Pedraza 2016; De Llano Neira 2015; Mandujano 2016).

Following a reorganization of Mexico’s network of election authorities, with greater powers allocated to the federal entity, online voting was reconsidered as a way to reduce costs and facilitate voting for citizens abroad. The first official implementation at the federal level took place in 2022 for a recall procedure (INE 2022). Some state entities had already used online voting in 2021 (INE 2021). While postal voting was already available from abroad, in 2024 voting machines were distributed to certain embassies for the presidential race (INE 2024b, 2024c; Castillo 2024).

In 2024, 122,497 citizens cast their ballots over the Internet, representing 66.45 per cent of all ballots cast from abroad (INE 2024e: 41, n.d.a). While this is still a small fraction of the huge Mexican diaspora, it is larger than previous exercises (98,470 votes from abroad for the presidential race in 2018, 40,714 in 2012 and 32,621 in 2006) (INE n.d.b). The general voters’ list in Mexico in 2024 comprised 98,329,591 people (INE 2024d).

Civil society organizations have attempted to use the detailed legislation related to access to public information (R3D 2023a) to obtain information on audit conclusions. The courts have established criteria on how to weigh contradictory interests in relation to transparency and the security of the electoral process. (See, for instance, Recurso de Amparo 245/2022, 10th Administrative Tribunal/1st Circuit/México City, INAI 2023a, 2023b, 2023c.)

Switzerland

In June 2023, Switzerland resumed online voting pilots in three cantons (Federal Chancellery of Switzerland n.d.a). After long experience that began in another three cantons (Geneva, Neuchatel and Zurich) using different technologies in each, and then spread to other territories, online voting was put on hold in 2019. A public intrusion test identified ‘flaws in the individually verifiable system’ in one of the online voting solutions put in place (Federal Chancellery of Switzerland n.d.b).

Online voting complements other special voting arrangements, such as broadly accepted and much-used postal voting. Moreover, online voting, while having legal binding effects, is capped to limit its effects and keep the project as a pilot. Online voting is therefore accepted provided that it does not go beyond a certain percentage of voters (see Ordonnance sur les droits polítiques, 1978, article 27f). While the system is addressed to all voters, any constraints do not apply to overseas ones or citizens with disabilities, as these are the target-groups that have the most immediate benefit from online voting. While online voting would not have any disruptive effects for citizens living in Switzerland (Germann and Serdült 2017), there is one study demonstrating a 5 per cent decrease of turnout among citizens living abroad, in the event that online voting is suspended (Germann 2021).

According to an Office for Democratic Institutions and Human Rights report on 2023 elections (OSCE/ODIHR 2024), areas for improvement include the composition of the electoral board, and its independence when sharing cryptographic keys, and the recruitment process for external experts to review the system. These are intended to replace the previous formal certification system that in 2019 failed to reveal weaknesses and implement another procedure with which an open multi-stakeholder consultation is launched for ‘increasing transparency and trust’ together with ‘effective control and oversight’ (Federal Chancellery of Switzerland n.d.a).

1.3. Recent new cases

El Salvador

Following elections where OCV took place by post (TSESV 2019), in 2024 citizens abroad were allowed to vote electronically (TSESV 2023), either in-person or remotely (TSESV 2024a), for the presidential election. Remote voting was available some weeks in advance (TSESV 2024b) of election day. Turnout in 2024 (i.e. 242,110 online ballots and 89,646 ballots cast with voting machines) was much higher than in 2019 (3,808 ballots received from abroad) (OAS 2019: 12; Crespín 2024).

International observers were informed that some files were illegible and temporarily prevented clarification of the total number of votes cast. The report also mentions that the supplier admitted that there had been a software failure (OAS 2024: 17; Diario El Mundo 2024). In general terms, limited EMB ownership and engagement regarding how to implement online voting was noted by observers (OAS 2024: 16–17). Concerns were raised about effective oversight by political parties as the nature of online voting makes such tasks more difficult.

International observers recommended, among other things, enhancing the role of party agents for effective monitoring, increased EMB capacity and in-house expertise or strengthening audit and more timely supervision of online voting devices and components, including an external computer forensic audit.

According to local interlocutors, there is room for improvement in terms of EMB communications protocols to be fully prepared for information technology (IT)-based crisis scenarios. Further knowledge of the intricacies of online voting and speedier consultations among concerned EMB units would also be useful.

Oman

In 2011, Oman launched a project to improve the electoral process for the Majlis Al-Shura, which is the main representative assembly in the country. In particular, biometric features for voter authentication together with counting machines were implemented (Valeri 2012; Khaleej Times 2015; Sakhar al Amry 2016). In 2015 (Oman Daily Observer 2015; Al Ghadani 2015; Times of Oman 2015), electronic voting was first used within controlled environments for expats and polling staff. In 2019, voting machines were available for a wider public (Ministry of Interior, Oman (MOI) 2019) and expats could already vote remotely using a dedicated application (Al-Bulushi n.d.; Muscat Daily 2019). Finally, the 2023 elections became fully digitalized, without polling stations (Times of Oman 2023), and the application-based online system, with certain features improved, the only voting channel (Ministry of Interior, Oman (MOI) 2023a). Turnout wise (Ministry of Interior, Oman (MOI) 2023b), ‘753,260 of a total of 1,–6,556 (49.67%) Omanis aged 21 and over registered to vote for this election, 362,611 women (48.14%) and 390,649 men (51.86%). A total of 496,279 Omanis (65.88% of those registered to vote) cast their ballots, 237,432 women (65,48%) and 258,847 men (66.26%)’ (Guirado Alonso 2024). These figures increased if compared with previous elections and they included ‘13,843 Omanis living abroad’ (Msuya 2023). Voter authentication is conducted through biometric tools that combine facial recognition with smartphones capable of reading the digital ID card (Tech5 2023).

Panama

Online voting in Panama began just for overseas voters in 2014 (OAS 2014: 3). OCV had been launched for previous elections (TE 2007; OAS 2009: 20–21), with limited voting channels, such as postal voting, which according to local interlocutors proved to be expensive and only a limited success in terms of turnout. Cost evaluations and turnout expectations led to online voting being seen as a promising solution. For the 2024 elections (TE 2024d, 2024e, 2024f), the online channel was implemented as an advance voting option for expatriates and other target groups, with improvements aimed at making the process easier for voters (for instance, PIN codes were no longer sent by SMS). While in 2019 (Emb. Rusia 2019) turnout figures among already registered online voters had been quite low (1,374) (TE 2019b; Paz 2019), these improved a little in 2024 (3,596) (TE 2024c: 27) thanks to the innovations put in place.

Unexpected problems occurred when, after online voting had been launched, a mismatch between the layout of the paper and electronic ballots was discovered (TE 2024a). After a temporary suspension of the procedure, online voting resumed (TE 2024a, 2024b), although a parallel initiative using voting machines in Panama was annulled (TE 2024g).

The Philippines

Voting machines were already in place domestically. Initiatives to implement online voting mainly targeted overseas voters, the enfranchisement of whom could not be fully achieved with the methods in place in the 2019 elections, such as in-person and postal voting (Comelec 2020). Seafarers, for instance, were one of the most important groups to address (MARINA 2023).

The legislative framework was amended in 2013. According to the new law, a commission will be able to ‘explore other more efficient, reliable and secure modes or systems, ensuring the secrecy and sanctity of the entire process, whether paper-based, electronic-based or Internet-based technology’ (Republic Act 10590, 27 May 2013, section 28).

Heading into the 2025 elections, the Philippines foresaw a binding trial involving expatriates living in certain countries (Comelec 2024c). In 2021, different phases, such as ‘preparation and presentation’ (Comelec 2021d) or the Internet voting tests had been already completed (Comelec 2021a, 2021b, 2021c). As of September 2024, the countries from where online voting will be available were determined (Comelec 2024d), the relevant regulations adopted (Comelec 2024e), a specific ID authentication had been launched (Comelec 2024a), training sessions had been carried out (Comelec 2024b) and, among other aspects, a tender process had been conducted (Bordey 2024; Panti 2024). Citizen observers appeared supportive of the initiative. Different tests were foreseen encompassing lab controls, limited field evaluations and mock exercises. Finally, online voting was implemented for overseas voters in the 2025 elections, with approximately 232,000 ballots cast (Abad 2025).

In terms of transparency, the system is to be audited by international experts and the local IT community would have access to the source code. An ad hoc committee of official state agencies will evaluate all reports and make relevant recommendations to the election authority and the national parliament.

Russia

Following experience with voting machines (Russian Federation 2006), tests of online voting began in Moscow in 2019 (Epifanova 2021; Melkonyants 2019) and progressively expanded in scope (during the pandemic, see Krivonosova 2020: 7, 12–13) until the elections in 2024 (Andreichuk 2024; Golos 2024), when nearly one-third of regions (Russian Government 2024) used such procedures. During this period of expansion, at least two systems (RBC 2021) ran in parallel, one for Moscow and the other one for eligible regions.

Given that Russian online voting is not available for overseas citizens, the rationale cannot be increased accessibility aimed at enfranchising expatriates, as is the case in other countries. Instead, online voting could have other aims (Romanov and Kabanov 2020: 237; Carmichael and Romanov 2022: 135). In authoritarian regimes, online voting may become instrumental in electoral fraud (Pertsev 2024). Online voting is available to all those who have completed a registration process (Tass 2023), where personal data is checked. Notable turnout figures of more than 8 million ballots (Shvetsova 2024; Tass 2024a, 2024b) were reported among voters registered for online voting. In terms of transparency (Andreichuk 2024) and reliability, procedures evolved from online voting’s first implementations. Discussions with IT experts were held to identify gaps (Криптонит 2023), but in some cases the parties involved did not complete their observation tasks, having reportedly not been given enough information about the system (Rozhkova 2022).

1.4. Suspended

Australia

Beyond a limited trial in 2007 for military personnel abroad and other projects based on local machines to enhance accessibility (Parliament of Australia 2016: 10–12; Commonwealh of Australia 2009; Electoral Council of Australia & New Zealand 2013), New South Wales (NSW) started using online voting in Australia in 2011 and ended implementation in 2021 (NSW Electoral Commission 2025a), when ‘671,594 votes were cast, compared with 234,401 at the 2019 NSW State election’ (NSW Electoral Commission 2022a: 51). Western Australia examined online voting in 2017 (WAEC 2016: 7) and the ACT (Australian Capital Territory) in 2020 (ACT Electoral Commission 2021).

In NSW, as required by law, online voting was offered as an additional channel and targeted a variety of groups. While originally targeted at blind people or persons with restricted vision, the range of profiles later covered voters not able to attend polling stations on election day or those living either abroad or in remote places.

Feasibility reports (NSW Electoral Commission 2010) were produced before launching the initiative. While private sector companies were hired to support and audit the process, according to EMB staff the election commission retained key IT functions to ensure ownership and oversight of the procedure.

Online voting was discontinued due to the time constraints involved in having to update the system (NSW Electoral Commission 2022b). Various technical problems regarding the capacity to issue the relevant voter credentials had also been identified during the 2021 elections, which led to certain elections being declared void (NSW Electoral Commission 2021, 2022a: 51–53). In 2015, independent scholars were already challenging the system, reporting certain vulnerabilities (NSW Electoral Commission 2015). Significantly, telephone assisted voting was still available for the 2025 local elections (NSW Electoral Commission 2025b).

Ecuador

Ecuador has been piloting different electronic voting systems since 2004 (CNE 2014: 4–7), but none has been implemented nationwide. According with the legal provisions (Dis. Transitoria Novena/Código de la Democracia), a new Internet voting project was launched in 2021 for general elections and a presidential runoff, for use in consulates. Postal voting together with voting machines abroad were also piloted on that occasion. Compared to districts using ballot box voting, ‘overall turnout increased respectively by 13.09% and 12.12% in the district using Internet voting’ (Dandoy and Umpierrez de Reguero 2021). Reports by international organizations noted that EMB ownership could be improved with better information received from suppliers as well as greater EMB involvement in designing security features and testing (OAS 2023a: 87). A ‘significant gap’ was also identified between people on the electoral roll (567) and those with registered emails enabling them to vote (360) (OAS 2023a: 30).

Two elections took place in 2023: planned municipal elections together with a constitutional referendum and fresh general elections organized at very short notice. While the former used online voting that encompassed a wider range of 52 constituencies abroad (CNE 2022), the latter experienced full deployment for all 101 overseas constituencies (CNE 2023b). Despite improvements made by the supplier, problems were noted on election day and contradictory information was provided (OAS 2023b). Tallying procedures were problematic: public sessions were suspended and clear information was still lacking 48 hours after polls closed (OAS 2023b: 12). The results from the voting abroad were eventually annulled (OAS 2023c). Significantly, the EMB had outsourced the project to different entities so that elections in 2023 (CGE Ecuador 2024a, 2024b) were not handled by the company that had been involved since 2021 (Celi 2023; ESPE Innovativa 2023).

Online voting took place together with the regular voting in Ecuador, that is, no advance voting was foreseen. According to local interlocutors, the election authorities had no specific legal authorization beforehand to tailor such features.

Finland

In 2008, Finland (Vaalit Val n.d.) decided to test online voting in supervised environments with binding effects in three municipalities: Kauniainen (6,391 voters), Karkkila (7,112 voters) and Vihti (20,559 voters) (Whitmore 2008: 6). The project was not further developed afterwards.

Pitfalls discovered during the tally led the courts to annul the results and repeat the elections (Aaltonen 2016). The figures did not match since the number of ballots registered by voting machines (i.e. 12,234; see Whitmore 2008: 57) was lower than the voters registered in the relevant polling books, or the people who had attended the polling station to cast a ballot. The gap encompassed 232 cases (Vähä-Sipilä 2019: 6). One explanation was that the voting interface and the need to confirm the ballot on a different screen after selecting the relevant options meant that some voters would have thought that they had voted when they had just selected options. If they did not complete the entire procedure, the voting machine did not record them as voters and the figures became mismatched (Whitmore 2008: 25).

Consideration should also be given to another aspect of the Finnish online voting experience related to the audits conducted of the IT platform. While an audit was completed by local stakeholders, others refused to do so in the light of the constraints incorporated into a proposed non-disclosure agreement (Tarvainen 2008).

The Netherlands

The Netherlands (Loeber 2008; Jacobs and Pieters 2009) was one of a small number of front runners in the implementation of electronic voting, using on-site machines in the 1960s and online voting in 2004 (Loeber 2008: 23). In 2004, most of the approximately 25,000 overseas voters chose online voting instead of telephone voting. In 2006, 19,815 online ballots were cast (Loeber 2008: 27; OSCE/ODIHR 2007: 14). Notwithstanding certain incidents, these technologies were widely accepted and presented as totally reliable devices only capable of undertaking election-related tasks.

Against this relaxed backdrop, in 2006 unexpected criticisms calling into question the reliability of voting machines were raised by a local non-governmental organization. Tests proved that they could be used for purposes other than electoral activities, and that voters’ decisions could be tracked and thus the secrecy of the vote breached (Votingcomputerleak 2006; Goldsmith and Ruthrauff 2013: 268).

These findings prompted an in-depth review of the electoral process by public committees and a decision was taken to discontinue the use of voting machines, which had been targeted by the tests, but also of online voting, which was examined in 2008 within the context of waterboard elections showing, among other aspects, a weak encryption system (Loeber 2014).

Norway

Norway has a limited but interesting record when it comes to implementation of online voting (Government of Norway 2019). The government first took an interest in the topic after countries such as Estonia and Switzerland had already implemented schemes and criticisms had already surfaced related to transparency and accountability. The ruling of the German Federal Constitutional Court (see below) referred to voting machines, but the grounds were applicable to any form of electronic voting. These technologies could easily become a black box procedure not capable of providing meaningful verifiability for all voters. The Norwegian project built on such previous cases and intended to provide advanced features capable of overcoming problems. End-to-end (E2E) verifiability is an example of these new measures (Gebhardt Stenerud and Bull 2012; Barrat et al. 2012).

Box 1.1. End-to-end verifiability

E2E verifiability constitutes a major innovation for online voting systems as it seeks to address some of its structural weaknesses. It provides evidence that ballots have been cast as intended, recorded as cast and finally, as a universal option, tallied as recorded. The first two steps, which are known as individual verifiability, facilitate voter involvement as voters are supposed to check whether the evidence matches their political choice. In Norway, return codes are put in place to that end (Barrat et al. 2012). These indicate the content of the ballot and are sent to a voter’s second device (i.e. mobile phone). Tallied as recorded, on the other hand is based on software-independent mathematical proofs that any expert can undertake on their own. E2E verifiability addresses certain traditional concerns related to online voting and targets the integrity of the results, but not aspects such as the secrecy and anonymity of the ballot which are also crucial to the integrity of elections.

Pioneered in Norway, other countries later adopted this new generation of online voting platforms. As often happens with other election mechanisms, expectations and settings were adjusted to each context. In Switzerland, for instance, full verifiability was used as an indicator (Federal Chancellery of Switzerland 2023) that allowed cantons that met such a standard to go beyond the percentage ceilings established for online voting. As a result of a reformulation of the entire system, new regulations were approved and caps now apply regardless of whether E2E verifiability is in place: ‘limiting the proportion of the electorate to the previous lowest category underscores that this is a trial phase of electronic voting’ (see Federal Chancellery of Switzerland n.d.c, article 27f). Ceilings do not apply to citizens abroad and people with disabilities. On another note, the concept of full verifiability also encompasses the ability of a non-voter to check that no ballot has been cast on their behalf (Ordonnance sur le vote électronique, 1978, article 5.2b).

In Estonia, the online voting system was upgraded to allow verifiability functions, but concrete features differ. Estonian return codes, for instance, are based on a QR system and a specific verification app is needed. Moreover, the information about the voter’s choice can be retrieved up to three times during 15 minutes after the ballot was cast, and is visible for a maximum of 30 seconds (Valimised n.d.a).

It is worth noting that E2E verifiability is a sophisticated technique and proper implementation requires:

- the involvement of a heterogeneous pool of IT experts to conduct mathematical proofs on the integrity of the results;

- trust assumptions connected to the extent to which voters verify their ballots and the percentage of electors who do so; and

- awareness that voting receipts, even with alphanumerical codes, do not necessarily mean that E2E verifiable systems are in place. Other requirements might be needed, such as a second electronic device to check the voter’s choice, that is, not just a generic confirmation that the process was well performed.

Norway started with a limited binding test in certain municipalities in 2011 and the pilot continued in 2013 with similar scope. After this second step, however, the project was discontinued, due to political disagreements about the desirability of online voting (Government of Norway 2014). Online voting remained limited to local consultations (e.g. Innlandet in 2022 and Finnmark in 2018; see Smartmatic 2022a, 2022b). For the 2011 pilots, there were ‘no indications that the trend in turnout in the trial municipalities deviates from the country as a whole’. This applied to both aggregate figures and turnout rates per group of voters (Government of Norway 2012). In 2013, there were no indications of turnout changes either, although over 30 per cent of voters chose the online voting channel in comparison with 26 per cent two years before (Government of Norway 2013b: 135). Significantly, ‘voter turnout among citizens living abroad … is nine percentage points higher than for citizens living abroad registered in municipalities that were not taking part in the trial’ (Government of Norway 2013b: 137).

Pakistan

Pakistan used Internet voting as pilot test for bye-elections in 2018 (ECP Pakistan n.d.) and, after issuing the relevant report, the project was not further developed. This pilot was a key milestone in a larger project to enfranchise the diaspora, which is very important in Pakistan. After a less than successful attempt at telephone voting in 2015 (Binte Haq, McDermott and Taha 2019), the Supreme Court instructed the Election Commission in 2018 to set up an Internet voting system for the elections to be held a few months later (Lahore High Court 2018). The decision was taken on the basis that overseas voting is an actual right that should not to be undermined by technical constraints but ‘must necessarily be given due effect’.

Following the Supreme Court ruling, a task force (ECP Pakistan 2018) was formed to prepare the project. Out of 631,909 eligible voters, 7,364 (1.2 per cent) were successfully re-registered for the online voting pilot and 6,146 (83.5 per cent of the registered voters) did cast their votes (ECP Pakistan n.d.: 10–11). In the aftermath of the 2018 elections, different reports (ECP Pakistan n.d.; Indra 2021), both external and internal, assessed the outcome and whether the system should remain in place. In general terms, the conclusions determined that online voting for future pilot tests needed improvements to meet international standards. Therefore, different update phases were needed before future implementation (ECP Pakistan 2022: 101). Internet voting has not been used again since.

USA

Absentee voting has always been a topic of interest in the USA and the role of military personnel abroad is particularly important in this regard (see the Uniformed and Overseas Citizens Absentee Voting Act 1986 and the Military and Overseas Voter Empowerment Act 2009). For these reasons, various initiatives were launched in the early 2000s to assess the feasibility of online voting mechanisms. Such projects ran in parallel with binding schemes for primary elections, for example, in Arizona (EAC 2011: 15–16).

In December 1999, a White House Memorandum asked the National Science Foundation to conduct a feasibility study on online voting (IPI 2001: 42; see also California Internet Voting Task Force 2000). The Federal Voting Assistance Program (FVAP) was also asked to investigate the topic. A limited Internet voting project was undertaken for the 2000 federal elections in which 84 binding ballots were cast over the Internet, although, due to its pilot format, there was no tabulation process. The ballots were electronically randomized and later transcribed by local officials on to standard absentee paper ballots (FVAP 2001). Later projects were cancelled (FVAP 2015: 13) before implementation, such as the Secure Electronic Registration and Voting Experiment (SERVE) for the 2004 elections (FVAP 2015: 13–15; EAC 2011: 29–32) or a proposal by the District of Columbia in 2010, which was based on a PDF return ballot scheme (EAC 2011: 19–20).

In 2008, the Okaloosa (Florida) online voting project (EAC 2011: 23–27; Alvarez and Hall 2013) was implemented, as a small-scale initiative focused on military personnel abroad. This was based on kiosks set up in controlled environments. Traditional voter authentication procedures were implemented and there was a paper trail issued for each of the 93 ballots cast. In the 2010 elections in West Virginia (Tennant 2010; EAC 2011: 32–34), overseas voters belonging to eight counties cast ballots over the Internet with neither kiosks nor a paper trail. A 2019 report by the Senate Select Committee on Russian interference in the 2016 elections concluded that ‘States should resist pushes for online voting [since no such system] has yet established itself as secure’ (US Senate 2019: 59–60). Besides those examples compiled by the Election Assistance Commission in 2011, voters cannot vote online in federal races (US GSA n.d.).

Electronic return ballots are available in some states, allowing certain groups of voters to download the ballot, fill it out and even send it back via app or web portal. The ballot is then printed out and tabulated with all the other ones. In 2024 West Virginia elections, for instance, return overseas ‘ballots are verified and tabulated by the local elections office’ (State of West Virginia n.d., 2020).

According to the National Conference of States Legislatures, electronic return ballots cannot provide full anonymity since ‘election officials can identify the person who returned a ballot electronically’ (NCSL 2024, with a table of details from all states; see also Verified Voting n.d.; CISA 2024). While there are different types of return ballot systems and some of them use apps and cryptographic protections for voter privacy (GBA 2022: 16, 18, B1; Voatz 2020), electronic return ballots use to require the voter to waive the secrecy of the vote, including when the ballot is returned online, as was the case for West Virginia (State of West Virginia 2020: min. 03.14; 2024: 58) in 2020 and 2024. In 2018, there had been a blockchain-based system in place (Moore and Sawhney 2019; State of West Virginia 2018; Voatz n.d.a, n.d.b, n.d.c).

In 2023, the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency funded a research project and the early-stage solution proposed by VotingWorks was based on a ‘deployable terminal that would allow military voters to transmit a signed, encrypted digital ballot to their home precinct on election day using their common access card’. In parallel, the relevant printed ballot would be sent back to the USA for audit purposes (Adida et al. 2025; Clark 2024; Appel and Stark 2024).

1.5. Under discussion

Latvia

Latvia has been discussing online voting options since at least 2012 when the government submitted a proposal (Valsts kancelej 2013; Latvia 2012: section 76.6). However, a 2014 citizen petition was dismissed by the national assembly in accordance with government recommendations (Beitane 2016: 10). While neighbouring Estonia regularly appears as a benchmark, there is no consensus in Latvia. Discussions continue when new elections approach (LSM+ 2018, 2019; Kincis 2023), but no decision has been taken to implement electronic voting, mainly based on the idea that the technology is not yet secure enough for the delivery of official elections. Meanwhile, overseas voters are given the option to vote by mail and special arrangements exist for military personnel abroad (Centrālā vēlēšanu komisija 2023).

Nepal

In July 2023, a draft bill was introduced by the Election Commission of Nepal to enhance OCV and, among other provisions, consider online voting (The Rising Nepal 2024; Thapa 2024), provided the electoral authorities could be convinced that crucial aspects related to the integrity of elections could be protected: ‘… if the Election Commission is convinced of the security of the votes cast or to be cast through the information technology (online) system, there will be no obstacle …’ (section 204(5)) (NepalPage 2023). There have been no further developments since a new prime minister took office in July 2024.

South Korea

South Korea started using online voting in 2013, but with limited scope that targeted non-official elections (NEC 2013), such as internal decision-making procedures conducted by political parties. Despite this consolidated experience of so-called K-Voting (NEC n.d.), for the time being there are no plans to pilot online voting for official elections. The online voting system remains in place for public entities; it has been technically upgraded and blockchain tools are being considered (NEC 2017; MSIT 2020).

Online voting has obvious advantages compared to other special voting arrangements, but there are also concerns and trade-offs. Accessibility and inclusiveness are clearly enhanced, in particular for the diaspora since the network of polling stations abroad, both at consulates or in rented premises, is never granular enough to reach all eligible voters. Persons with reduced mobility also clearly benefit from the same advantages. Turnout can be expected to increase through such accessible voting mechanisms targeted at the often de facto disenfranchised. Online voting does also have a certain impact on voters’ habits (Solvak and Vassil 2018), but it does not seem to be a turning point to change persistent absenteeism.

The rapid transmission of results and the flexibility to use the tool for different types of citizen consultations, including referendums and other participatory processes, should be noted as other positive factors.

In terms of advantages, online voting also bypasses traditional logistical barriers linked to in-person procedures. Polling stations are no longer necessary and the same applies to voting materials, which are often delivered at very short notice, or cumbersome cascade training to raise awareness among polling staff. Deadlines are shorter and procedures easier for voters and EMBs, at least in certain respects.

Among this non-exhaustive list of positive factors might also be cost effectiveness, although no clear conclusions can be drawn in this regard since online voting entails certain budget lines that are not necessary for other voting channels (Krimmer et al. 2018) Last but not least, online voting might be just one component of a broader national strategy where cyber tools are seen as enhancing social progress and innovation. At some point therefore online voting cannot be detached from a more global trend for digitalization to become ever-present.

As noted above, compromises have to be made. Online voting usually means remote voting in the sense that ballots are cast from uncontrolled environments, which raises important concerns in terms of the secrecy and integrity of the ballot. While mitigation measures can be applied, online voting cannot be expected to replicate guarantees that only make sense in a controlled environment. Instead, online voting needs to find appropriate justifications elsewhere, for instance by comparing itself with other remote voting systems that are already accepted, such as postal voting. Revoting, for instance, as in Estonia, aims to address concerns related to secrecy and the freedom of the voter.

Voter registration and authentication also need to be duly tailored when online voting is in place. How ID credentials are managed and how eligibility is verified become much more complex and demanding when there are no controlled environments and almost no transactions can be performed in person.

Finally, transparency together with proper public accountability are issues that all online voting systems need to address. Online voting is a black box in that no easy-to-understand evidence is provided to test the performance of the system. Moreover, the principles of secrecy and anonymity, which are essential to electoral processes, make meaningful oversight much more difficult. While technically feasible, online voting systems must not reveal the content of ballots to track them back to individual voters. It is worth considering therefore the extent to which such constraints on transparency compensate for the gains obtained with online voting.

Box 2.1. Constitutionality of electronic voting

According to the Federal Constitutional Court of Germany (BVerfGe 2009), the public nature of elections means that voters and political parties should be granted meaningful oversight over the system. Given its highly sophisticated nature, online voting struggles to meet such a condition. Germany was using voting machines rather than online voting but the project was discontinued following this ruling. Voting machines in Germany did not include a paper trail at the time.

Policymakers should be aware of these constraints and, in addition to applying all compensatory measures, undertake the relevant risk assessments to ascertain whether online voting, having considered the advantages and disadvantages, achieves the relevant national interest in the sense of improving citizen engagement through appropriate electoral processes.

Along these lines, it is advisable not to consider online voting a stand-alone mechanism. There are various special voting arrangements (Barrat et al. 2023) and online voting should be analysed together with other channels that might have similar goals, such as postal, proxy or telephone voting. These are not incompatible and sometimes all are offered to citizens in an attempt to maximize accessibility. A broader scope can allow all stakeholders to consider the advantages and constraints of each.

Postal voting, for instance, offers flexible arrangements as it allows voters to cast the ballot remotely, but there are differences compared to online voting. First, documentation requirements in terms of how to distribute and return ballot papers and other sensitive materials are much more complex and expensive for postal voting, and often entail lengthy delays and lost votes due to late arrivals. Moreover, postal voting can require the voter to attend certain postal stations, which reduces its advantages as a flexible voting channel.

Proxy voting is an easy way to enfranchise people who would not otherwise be able to vote in person. It is a well-established voting method in certain countries, such as France. For the second round of the parliamentary elections in 2024, more than 1 million (Dermakarian 2024) voters asked for proxy votes. Compared to postal voting, documentation requirements are much lower. However, a major caveat may prevent proxy voting from becoming widely used since its implementation compromises direct and personal voting, which is the very basis of the entire electoral system. Proxy voting is therefore intended to be just an exceptional and complementary system.

Finally, telephone voting, which can be based on a mere phone call, is a sort of online voting but even more flexible since no computer device is needed. However, safeguards in this case might be less strict since cryptographic protections, which are crucial to online voting to guarantee the integrity of the results, might not be that easy to implement.

| Advantages | Challenges |

|---|---|

Accessibility/inclusivity Integrity of the results Cost effectiveness Rapid delivery of results Lower workload Environmental issues Logistics | Transparency EMB ownership IT obsolescence Legal guarantees Anonymity of the ballot Secrecy/freedom of the voter Verifiability |

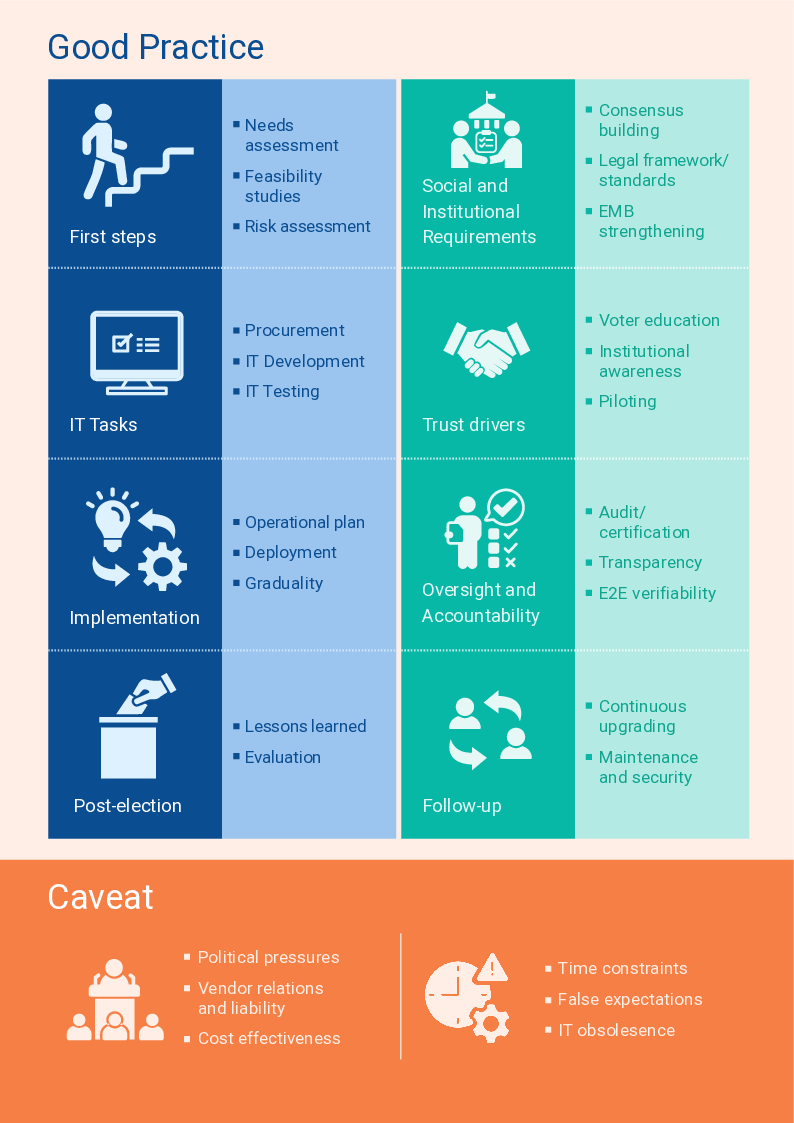

Having reviewed recent examples of online voting and considered its main advantages and risks, we can now highlight various parameters as important factors for the proper implementation of such a mechanism. These indicators can be used as lessons learned for countries aiming to implement similar online voting mechanisms in the short to medium term.

This chapter first addresses general factors such the context in which online voting is to be implemented, how to evaluate the risks involved and how to determine the feasibility of the project. These are preparatory phases that all online voting initiatives should conduct, although unfortunately this is not always the case.

Institutional factors come next, such as EMBs retaining ownership of the technology to be used in terms of knowledge and supervision procedures or the legal framework for providing a sound regulatory basis compliant with international standards. Crisis scenarios should also be foreseen as moments where institutions need to be equipped with all the necessary protocols to address urgent and challenging scenarios.

Operational aspects focus on areas where method of implementation becomes crucial, such as the extent to which online voting is compatible with other special voting arrangements or how to set up a voter registration/authentication system capable of verifying eligibility while at the same time paving the way for a smooth or not too cumbersome voting process. In addition, consideration is given to the calendar to be used for online voting and in particular the time span during which the voting period is open, or the election cycle as a temporal framework through which online voting initiatives are implemented.

Next, trust building is crucial since online voting’s ‘original sin’ is its limited transparency for election stakeholders and laypeople in general. Therefore, compensatory measures, such as individual and universal verifiability procedures, are necessary to keep stakeholders fully engaged. Audits and certification controls are also normally used to this end. The final section elaborates on how disruptive technologies, such as blockchain or quantum cryptography, could impact future online voting implementation and whether current cases already reflect such trends.

Having established a roadmap of strategic factors to be considered when using online voting, each factor is elaborated on below, while concrete examples are provided from the country cases.

3.1. Context matters

No single online voting solution will fit all the needs of all countries. Online voting is not a standard and uniform mechanism. While the core functions related to casting a ballot by digital means might resemble each other, there are also a number of important aspects that must be tailored to the specific context in which they are to be applied.

Estonia, for instance, accepts revoting and Switzerland establishes percentage ceilings on the total number of online voters. Ecuador aligns its online and in-person voting time periods but El Salvador offers advance voting through its digital channel. The United Arab Emirates provides polling kiosks where online voting is available, but in Mexico such controlled environments are just for voting machines. Finally, individual and universal verifiability, both of which are crucial components of more developed online voting, are implemented differently or not established at all, depending on the country and its context. There are many more aspects to consider when completing a detailed picture of online voting technologies, but the above distinctions are important enough to make clear that the common category of online voting encompasses important nuances, and such flexibility is directly connected to how each country proceeds.

A contextual approach is particularly important when it comes to trust building, since every country considering online voting tools has different sociopolitical traditions, and a variety of expectations and strategies in terms of public decision making and stakeholder involvement. The tool must therefore be adjusted to contextual needs, not the other way around. Both EMBs and vendors should be aware that local awareness and introspection are needed to agree on electoral priorities and needs, and to establish a roadmap on how to achieve these. Mere templates or experiences should not be recycled from one country to another. While lessons learned from other experiences are useful, local ownership is also needed and mimicking strategies is likely to fail.

In this regard, a proper risk assessment together with a feasibility study should be considered. Both documents need to be context based as conditions can vary a great deal.

Box 3.1. Online voting as part of a national digital strategy: The case of Estonia

The Estonian case is often used as a benchmark to be transferred to other countries, but such assessments tend to forget the contextual factors that surround online voting implementation.

The main features that should be highlighted for the Estonian context consist at least of the size of the country and its known familiarity with cyber issues. Estonia has a population of around 1.4 million, which makes projects on special voting arrangements much easier to implement compared to in larger countries. Moreover, it is not only a matter of size in logistics terms. Regardless of discussions and even controversies, stakeholder involvement and building trust are easier in Estonia and more complicated in other countries. The independence process in the early 1990s might have also played a role in advocacy for technologically advanced voting systems.

In any case, a second and perhaps more important factor is that Estonia has a long and solid tradition when it comes to the development of cyber tools, dating back to the Soviet era (Velmet 2025; IOC 2023) and consolidated afterwards as a way to distinguish the country on independence

Finally, Estonian Internet voting is well known thanks to its very particular function that allows citizens to revote several times. It cannot be properly explained without taking context into consideration, as well as how the secrecy of the ballot is perceived in Estonia, a country where postal voting is not permitted (Madise and Vinkel 2011: section 3.1).

3.2. Risk evaluations and feasibility studies

Estonia is the only country where online voting is available nationwide for any election, together with other voting methods. In all other cases, including Canada and Armenia, online voting is used with important caveats. Canada does not use online voting for federal races. The Armenian system is only available to some hundreds of voters, mainly diplomats, their family members and military personnel abroad, which is a tiny fraction of its diaspora. Other countries, such as France and in Latin America, limit online voting to OCV or place certain conditions on its implementation (see 1.2: Suspended or reintroduced, Switzerland).

There are different rationales for these strategies, often based on previous risk assessments and the need to limit the potentially harmful effects of online voting. This is pretty clear, for instance, in Armenia, where the hundreds of eligible voters will likely not be able to modify the final outcome. The ceilings established in Switzerland that limit online voting to a percentage of voters have the aim of combining innovative voting methods with retaining some control over their ultimate effects. As the Swiss authorities note, referring to Internet voting, they apply the principle of ‘security before speed’ (Federal Chancellery of Switzerland n.d.a).

The sophistication of the system and the range of safeguards in place are linked to relevant risk assessments. A low-key online voting system could be functional in a limited environment mostly for certain civil servants, as is the case in Armenia, but global implementation might require additional resources, supplementary layers of security and even an entirely different decision-making process.

The above examples illustrate the importance of a sound risk assessment from the very beginning. At the same time, however, this evaluation cannot be limited to technical variables. It should also be a social/cultural process through which citizens understand what online voting can provide and assess whether it meets the public interest, and at what cost. Some countries may conclude that the risks are too high even having considered the benefits of online voting. South Korea, for instance, which uses online voting for internal decision making for political parties, has decided not to implement it for official elections. Pakistan has taken a similar approach.

In this regard, risk assessments should be treated as social trust builders. While IT devices used to be launched accompanied by rigorous risk assessments of all kinds of technical pitfalls, online voting risk evaluations need to go much further to consider, among other aspects, whether the relevant society is aware of and ready to accept the risks that online voting, or any special voting arrangements, entail. A positive outcome from such additional perspectives would pave the way for stable implementation. Policymakers will know where to focus, which caveats to consider and in general terms how to align IT requirements to social expectations and positive outcomes.

Feasibility studies would complement this risk-based approach with a supplementary range of variables to be assessed. Here, the integrity of the election is no longer at stake, as it was with the risk evaluation, but attention should be paid to different indicators, such as cost, human resources, legal framework and operational components.

Despite the obvious advantages offered by a process launched with a risk assessment and a complementary feasibility study, reality indicates that these often either do not happen or are conducted in such a way that precludes any lessons learned or sound conclusions to be drawn from the exercise. Reasons for such de facto deviations worth keeping in mind or avoiding are, among others, low institutional awareness of what online voting entails, as well as time pressures and deficient power sharing arrangements.

Online voting might appear to be an urgent remedy for electoral needs, such as fresh elections. Risks assessments might therefore be considered unnecessary, given other pressing requirements. Similarly, when public entities such as EMBs, government departments and data protection agencies, and perhaps private sector stakeholders, are deciding whether to implement online voting, unbalanced information and power sharing may lead to erroneous decisions, because the entity that was aware of the importance of risk assessments was not in the position to properly weigh such a proposal with the others. Latvia is an example of the contrary, where online voting has been discussed for over a decade but social and institutional factors have not led to its implementation. In Lithuania, a 2024 feasibility study recommended cautious and gradual implementation (Civitta 2024).

Box 3.2. How to assess Internet voting pilots: The case of Pakistan

The role of the diaspora in Pakistan is very important and there have long been discussions on how to enhance OCV. Beyond operational issues, which are crucial to ensure successful implementation of such voting channels, voters abroad should have not only the right, but also the opportunity to vote and, given these legal grounds, a solution has to be put in place whatever the barriers might be. In 2018, the Supreme Court followed this approach and, based on the constitutional framework establishing voters’ rights, instructed the Election Commission to implement a binding mechanism for overseas voters. Internet voting was adopted and developed in a very short timeframe with technical assistance from the National Database & Registration Authority (ECP Pakistan n.d.).

In the aftermath, and due to problems encountered during implementation, a new process was launched so that the 2018 pilots could be properly evaluated and, depending on the outcome, Internet voting be used in subsequent bye-elections. In this regard, election authorities undertook an assessment that included external audits, country visits, such as to Brazil in 2024 (Aziz 2024), and internal feasibility studies with a comparative perspective, legal premises, and operational and financial conditions. The entire process was intended to build on previous experience and decide what should come next. Internet voting was not used again.

3.3. EMB ownership

EMB ownership and whether the project is outsourced to private sector providers or other external stakeholders are often mentioned as major factors in the success or failure of online voting. The case studies confirm such assumptions. There are examples of unbalanced relationships leading to unexpected operational problems for which the EMB has no solutions. Good practices suggest a balanced combination of EMB oversight mechanisms and relevant involvement by suppliers.

Recent examples of online voting highlight different aspects of EMB ownership in particular. First and foremost, all stakeholders should have an initial understanding of the project’s complexity and the intricacies connected with implementation of online voting. However, sometimes even basic awareness is lacking among the main decision makers. There are misleading comparisons with other IT services, such as online banking, or flawed notions of online voting. In addition, some interlocutors highlighted the fact that, even when stakeholders are aware that more knowledge is needed, reliable sources of such data may not be easy to access, partially due to the range of languages available or the geographically unbalanced network of experts in this field. There is therefore room for improvement at this initial stage to make all stakeholders aware of online voting requirements and all the necessary information easy to access and process.

Once the decision is taken, EMBs should adjust their internal procedures to undertake a new and disruptive endeavour. Among the different pieces of EMB machinery to be reshaped, the IT unit and how to conduct training deserve special attention. Legal advisors would also need to update their portfolios.

In the IT unit, neither permanent staff nor advisors may be empowered to lead such a process. The unit could even be chronically understaffed. An easy and bad solution might be to hire experts who will create a parallel structure disconnected from the main department in charge of information systems, instead of reinforcing this taskforce. Decision makers might prefer to entirely outsource the project, giving the responsibility for all aspects to private sector companies, sometimes including those not directly related to IT issues.

In El Salvador, as noted by international observers in 2024 (OAS 2024: 16–17), EMB ownership struggled against the ‘preponderant role’ of the relevant supplier responsible for online and on-site electronic voting for overseas citizens. In one concrete example, certain premises serving as polling stations abroad caused problems when the rented timeframe did not match with voting hours. The electoral authorities stated that this was outside of their control since turnkey agreements were in place (TSESV 2024c: see in particular minute 08:10).

Whenever outsourcing is in place, EMBs should carefully consider the terms of reference so that the electoral authorities can retain meaningful oversight over the different phases of the project. To this end, in-house expertise as well as an efficient distribution of tasks should be available at the EMB level. Robust staffing and consistent training are also crucial. If not, the scope of the outsourcing procedure, non-disclosure agreements, reporting duties on the suppliers’ side, acceptance procedures or quality standards may not reflect what is necessary for the implementation of online voting. The EMB would no longer be leading the project, which is the best recipe for failure sooner rather than later.

Box 3.3. Online voting in federal countries

Canada, Mexico, Russia and Switzerland are federal countries that use online voting, which creates an institutional complexity that the different EMBs must deal with. There may be different online voting systems (e.g. Russia), with various suppliers (e.g. Canada), targeting a plurality of public entities, at the federal, state or even municipal level (e.g. Switzerland).

While in-house knowledge is required in all circumstances, coordination is crucial in these highly complex cases. Among other aspects, the legal framework, wherever appropriate, should make local initiatives possible while remaining compliant with general constitutional principles in terms of civil rights and election integrity. In this regard, a proper chain of accountability and oversight is necessary with principles and mechanisms carefully broken down from the federal layer to lower ones. Areas such as training, voter identification/authentication and online voting certification may require sophisticated cooperation mechanisms too.

While the challenges might be similar, solutions can vary from one federal country to another. While in certain countries federal agents might not be directly involved in how subnational bodies conduct online voting exercises, in Mexico, following a reform that reduced the role of state EMBs (TEPJF n.d.), the federal EMB now leads such initiatives to enhance voting from abroad, either for federal or for state-level elections. Finally, the Swiss system is based on active engagement with the Federal Chancellery, which develops the ground rules and main principles laid down in federal law. Cantons should follow these criteria for conducting elections and votes at the federal/national level.

Canada, Russia and Switzerland operate different systems and the overall legal and operational frameworks should be flexible enough to incorporate different solutions under a common umbrella governed by consistent principles. Intertwining systems and administrations is a challenge that all federal states face when implementing public services and online voting is no exception.

3.4. Legal frameworks

Election law has traditionally been highly detailed so that governments had less room for manoeuvre in such a sensitive field, but this is less the case when it comes to how online voting is regulated. Various factors tend to lead to brief provisions at the highest legal level, either constitutional or parliamentary, and widespread referrals to governmental instructions. Among other reasons, it would not be appropriate to place detailed technical provisions that might quickly become outdated in a parliamentary law. Pilot projects or a careful approach to introducing online voting might also lead to short, and necessarily incomplete, legal provisions, albeit with important consequences in terms of institutional checks and balances.

Different concrete cases can be used to illustrate these assumptions. Among other general referrals to governmental regulations, attention should be paid to the ones that combine delegations of power and constraints at a legal level that intend to reduce the margin of governments and election authorities at least a little. Legislators want to establish certain caveats. In Nepal, for instance, a draft bill on OCV gave permission to use online voting provided the election authorities were convinced that certain principles would be well protected (NepalPage 2023). For another example, see Ecuador and references to the state-of-the-art technology below. One might wonder about the actual effect of such legal provisions and when or how the authorities could provide evidence that they are convinced. Such strategies seem to be attempts to justify what might be unavoidable when regulating online voting—the broad empowerment of administrative entities instead of the active involvement of parliamentary assemblies.

In any case, a balance must be sought on the place of legislation and relevant safeguards. Short provisions or even blanket power delegation, as noted above, might be an effective and easy shortcut for policymakers, but they leave behind a normative vacuum and are likely to lead to different guarantees than those inherent in a legislative process.

On the other hand, delegation of powers, if not well done, might not achieve the intended goal. This was the case in Ecuador where, according to interlocutors, the timeframe for online voting was necessarily aligned to the one for regular voting due to the lack alternative legal provisions. The law allowed online voting and it even prioritized its use for citizens living abroad (Código de la Democracia and Dis. Transitoria Novena, article 113). It enabled election authorities to ‘introducir modificaciones a su normativa de acuerdo al desarrollo de la tecnología’ [include changes for their regulations to be aligned with the development of technology] (article 113; emphasis added), but no further details were provided. While the election authorities understood that technical arrangements would be covered by such provisions, they also interpreted that aspects such as the voting period should be established by law and, if not the case, general provisions for regular voting still applied. Therefore, and contrary to good practice, online voting was not conceived as advance voting.

Again, a balance should be sought between the flexible provisions required by an evolving technology, as noted in the above quote, and certain basic features where online voting might depart from what is used for regular voting. Due to their crucial role, as in the case of the voting period, this cannot be established by mere regulations. Prudent sentences instructing the election authorities to double check the reliability of online voting (e.g. ‘garantizando las seguridades y facilidades suficientes’ [ensuring enough security safeguards and functionalities]) cannot substitute for earlier decisions taken by parliamentary assemblies. Therefore, legislators should be fully aware of all the intricacies and requirements of online voting and, from such a starting point, decide what should go where in either legal provisions or regulations. In Estonia, for the sake of clarity and legal certainty, the election law was amended in 2024 with the explicit intention of including details at the parliamentary level that had previously been addressed only by administrative regulations (OSCE/ODIHR 2025; Tõnisson 2023).

In Ecuador, a temporary legislative provision asked for enough advance voting time in case of postal means (‘con suficiente anticipación’ [early enough]/Dis. Transitoria Novena/Código de la Democracia), but significantly it did not proceed in the same way for online voting, even though both channels were included in the same legal provision. In this regard, mention should be made of El Salvador where the law explicitly establishes a 30-day voting period (Asamblea Nacional 2022: article 16). Beyond the appropriateness of such a lengthy process, which is discussed below, the fact that the law already addresses these aspects should be deemed a positive indicator.