Navigating the European Union’s Digital Regulatory Framework: Part 1

A Compact Overview of Its Impact on Electoral Processes

Digitalization is reshaping electoral processes across the European Union and its neighbouring countries that aspire to join. While it offers powerful tools to enhance democratic participation, it also introduces new vulnerabilities—ranging from non-transparent political finance in online campaigning and disinformation to foreign interference and cybersecurity threats. These challenges demand robust digital governance and vigilant oversight to ensure that elections remain free, fair and transparent both within and beyond EU borders.

To this end, the EU’s comprehensive digital acquis serves as a cornerstone of democratic resilience. This body of legislation significantly influences the organization and conduct of elections, including in countries seeking EU membership. These countries, often facing resource constraints, must navigate the process of approximating the acquis while also addressing pressing challenges such as foreign interference and the effective oversight of online campaigning. In turn, the frontline experiences of enlargement countries can offer valuable lessons for the EU itself.

This research, titled Navigating the European Union’s Digital Regulatory Framework, is developed under the project Closing the Digital Gap on Elections in EU Accession, funded by Stiftung Mercator. It comprises two complementary parts that together aim to address a critical gap in the interaction between the EU and candidate and potential candidate countries.

Part 1, A Compact Overview of Its Impact on Electoral Processes, explores the EU’s digital rulebook—anchored in landmark regulations such as the Artificial Intelligence Act, the Digital Services Act, the European Media Freedom Act, the General Data Protection Regulation and the Regulation on the Transparency and Targeting of Political Advertising. It offers a concise analysis of one of the world’s most comprehensive efforts to align technological innovation with democratic values. Through practical examples, it illustrates how these regulations help safeguard against cyberthreats, privacy breaches, unethical use of artificial intelligence (AI) in electoral processes, and opaque political advertising.

Part 2, Perspectives on Electoral Processes in EU Candidate Countries, examines the progress of candidate countries in aligning with the EU acquis. It assesses their legislation, institutional frameworks, enforcement capacities and experiences in addressing digital threats to elections. This section focuses on four candidate countries—Albania, Moldova, North Macedonia and Ukraine. Insights drawn from in-house and field research provide valuable input for both national and EU-level discussions.

The findings and recommendations presented here offer concise yet comprehensive guidance for electoral management bodies, policymakers and civil society organizations in accession countries, as well as for EU institutions. They also lay the groundwork for the next phase of the project, which aims to foster closer ties and exchange of knowledge among these actors.

This work is especially timely. The four accession countries have set ambitious goals to complete EU membership reforms by 2030, while the EU is intensifying efforts to fully enforce digital regulations to protect democratic institutions and elections—notably through the European Democracy Shield Initiative. This study supports those developments and contributes to strengthening the relationship between the EU and its aspirant members.

This mapping study provides a comprehensive overview of the European Union’s digital regulatory framework and its growing influence on democratic processes and electoral integrity. Rooted in the EU’s foundational values (i.e. democracy, the rule of law and fundamental rights), the study examines how key legislative instruments have been designed to address the complex challenges posed by digital technologies and their interactions with electoral processes. The analysis demonstrates how these regulations—including the Artificial Intelligence Act (2024), the Digital Services Act (2022), the European Media Freedom Act (2024), the General Data Protection Regulation (2016) and the Regulation on the Transparency and Targeting of Political Advertising (2024)—are collectively shaping a legal environment that upholds transparency, accountability and fairness in an increasingly digitalized electoral landscape.

Furthermore, the study underscores the importance of safeguarding fundamental rights in the context of data use, online content and artificial intelligence. It illustrates how the misuse of personal and sensitive data, opaque algorithmic systems and manipulative online practices threaten the integrity of electoral processes. Through legal analysis and jurisprudence from EU courts, the study highlights how democratic principles are protected through data minimization, proportionality, consent and transparency standards. These principles are critical in managing the risks posed by artificial intelligence–driven microtargeting, political advertising and content amplification, particularly on very large online platforms.

Case studies of the 2022 Hungarian parliamentary election and the 2024 Romanian presidential campaign vividly demonstrate the consequences of regulatory and enforcement gaps. These real-world examples reveal how online manipulation, disinformation and the failure to protect sensitive data can distort electoral outcomes and erode public trust. The study calls attention to the urgent need for more robust institutional cooperation, clearer regulatory mandates and consistent enforcement at the levels of both the EU and its member states.

From the perspective of electoral management bodies (EMBs) across EU member states, this evolving regulatory landscape presents both opportunities and significant operational challenges. EMBs are increasingly being assigned additional responsibilities, though their legal mandates and institutional capacities often vary widely. It is noteworthy that the implementation of the EU’s digital regulatory framework remains novel and poses challenges even for the most advanced member states, many of which continue to navigate complex legal, technical and institutional ecosystems in adapting to the evolving digital landscape.

Despite such complexities, the EU’s digital rulebook represents one of the most ambitious efforts globally to align technology governance with democratic values. Going forward, effective implementation will depend on the ability of EU institutions and the authorities in member states, including EMBs, to coordinate more closely, share good practices, and reinforce digital literacy and resilience throughout the electoral cycle.

In conclusion, the study positions the EU’s digital acquis as not only a framework for market regulation but also a vital instrument for democratic resilience. It calls for coordinated governance and vigilant oversight to ensure that technological innovation serves, rather than undermines, the values of open, fair and transparent democratic systems. Initiatives such as the European Democracy Shield exemplify this forward-looking approach, aiming to strengthen societal and institutional defences against evolving digital threats to democracy.

1.1. Democracy, fundamental rights and rule of law as core European values of the EU digital acquis

Democracy, the rule of law and respect for fundamental rights are core principles embedded in the founding treaties of the European Union. The principles mentioned in article 2 of the Treaty on European Union (TEU) serve as the cornerstone of EU policy and regulation, including the EU digital acquis.

The importance of article 2 of the TEU lies in its declaration:

The Union is founded on the values of respect for human dignity, freedom, democracy, equality, the rule of law and respect for human rights, including the rights of persons belonging to minorities. These values are common to the Member States in a society in which pluralism, non-discrimination, tolerance, justice, solidarity and equality between women and men prevail.

At the same time, article 6(1) of the TEU makes explicit reference to the Charter of Fundamental Rights of the European Union (the Charter), recognizing its legal value to be the same as that of the Treaties. The Court of Justice of the European Union (CJEU) has affirmed the binding nature of the Charter insofar as EU law is applicable and has played a crucial role in interpreting its provisions (CJEU 2021).

In addition to the Charter, article 6(3) of the TEU further reinforces the protection of fundamental rights by establishing that the rights guaranteed by the European Convention on Human Rights (ECHR) form general principles of EU law. With regard to the ECHR as a living instrument, the European Court of Human Rights (ECtHR) has played a significant role in shaping the understanding of these rights, influencing both national and EU legal frameworks.

The CJEU also takes ECtHR jurisprudence into account when interpreting fundamental rights under EU law, ensuring coherence between EU law and the broader European human rights framework and legitimizing CJEU statements (Tinière 2023: 328).

The EU’s commitment to an inclusive, fair, safe and sustainable digital transformation is enshrined in the European Declaration on Digital Rights and Principles. A first of its kind, the Declaration builds upon the Charter, citing article 2 of the TEU in stipulating that EU values, as well as the rights and freedoms enshrined in the EU’s legal framework, must be respected online as they are in the real world.

The above overview provides a clear picture of how fundamental rights, democracy and the rule of law are not only foundational principles of the EU but also legally binding obligations for both EU institutions and member states. By embedding these principles into the EU’s legal framework, including the digital acquis, the EU is ensuring that digital policies—such as those governing data protection (the General Data Protection Regulation, GDPR), platform regulation (the Digital Services Act, DSA), AI governance (Artificial Intelligence Act, AI Act), media freedom (European Media Freedom Act, EMFA), and political advertising transparency (Regulation on the Transparency and Targeting of Political Advertising, TTPA), among others—are aligned with fundamental rights.

Furthermore, the explicit reference in article 51(1) of the Charter reinforces member states’ obligation to respect these rights when implementing EU law, ensuring consistency in upholding democratic values and the rule of law across the Union.

This legal framework provides the foundation for safeguarding electoral integrity, protecting privacy and ensuring transparency in the digital space.

1.2. Protecting electoral integrity in EU jurisprudence: The role of the ECtHR and the CJEU in shaping elections

The EU’s digital policy is profoundly shaped by the foundational principles laid out in the TEU and the broader EU legal framework. This framework includes core documents such as the EU Charter of Fundamental Rights and the ECHR, as well as pivotal jurisprudence from the CJEU and the ECtHR. These principles underscore the EU’s commitment to upholding democratic values, including the integrity of elections, which is a cornerstone of any functioning democracy.

The right to free elections is enshrined in article 3 of Protocol No. 1 to the ECHR. This principle, as interpreted by the ECtHR, emphasizes transparency, accessibility and the protection of voters’ rights against external manipulation.

The ECtHR has progressively interpreted this article to address challenges posed by modern technological advancements, particularly in the realm of digital platforms. This evolution in jurisprudence underscores the importance of transparency, accessibility and the protection of voters’ rights against external manipulation in the digital age.

In Davydov and Others v Russia,1 the ECtHR emphasized the state’s positive obligation to ensure the integrity of the electoral process, including the careful regulation of the process in which the results of voting are ascertained, processed and recorded.

Additionally, the ECtHR offers a comprehensive guide highlighting the evolving nature of electoral rights, noting the necessity for member states to adapt their legal frameworks to address new challenges, including those arising from digital technologies. The guide underscores that the right to free elections encompasses not only the act of voting but also the broader context in which elections occur, including the information environment shaped by digital platforms (European Court of Human Rights 2024).

The CJEU has played a fundamental role in shaping EU policies around electoral integrity, especially regarding data protection and privacy. In Schwarz v Stadt Bochum,2 the Court emphasized the necessity of stringent data protection measures in electoral contexts, ensuring that voter data is handled responsibly. Further jurisprudence, such as in Digital Rights Ireland Ltd v Ireland,3 addressed the delicate balance between security concerns (data retention) and fundamental rights, influencing policies such as the GDPR.

The Planet49 GmbH case4 and Google v CNIL5 underscore the importance of explicit consent for data processing under the GDPR. While the Planet49 case emphasizes the need for active, informed consent (such as avoiding pre-checked boxes), the Google case highlights the territorial scope of privacy protections, specifically the right to be forgotten. These rulings, although not directly related to political microtargeting, illustrate the broader need for transparency in data collection practices and the protection of voters’ privacy in digital contexts, which is crucial for political campaigns that engage in microtargeting.

Lastly, the EU digital acquis is firmly rooted in the Union’s core values of democracy, the rule of law and fundamental rights, ensuring that digital transformation supports and does not undermine electoral integrity. Grounded in the TEU, the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union (TFEU) and the Charter, and shaped by CJEU and ECtHR jurisprudence, EU digital regulations such as the AI Act, the DSA, the GDPR, the EMFA and the TTPA collectively safeguard transparency, data protection, media freedom and fair political participation. This integrated legal framework ensures that the same rights and protections apply online as offline, preserving democratic processes in the digital age.

2.1. The right to privacy and personal data protection in electoral processes

Election authorities are increasingly gathering, analysing and using personal data to improve the efficiency of the electoral cycle. Electoral actors can use such data to identify voters, for voter registration and to deploy electoral campaigns, among other things. However, this reliance on personal data has created ongoing tension between data protection principles and electoral requirements. For example, while voter lists need to be transparent and accessible for scrutiny by electoral stakeholders, this need for openness can conflict with the obligation to safeguard individuals’ personal information.

Electoral authorities should acknowledge this tension and develop mechanisms that comply with both data protection principles and electoral requirements. In this vein, International IDEA has developed guidelines on the use of biometric technologies during elections (Wolf et al. 2017) and a database of the use of information and communication technologies (ICTs) in elections (International IDEA n.d.). These products should be used with the utmost caution and with an understanding of the serious challenges that reliance on digital technologies to improve the efficiency of electoral processes pose to the right to privacy and protection of personal data.

Accordingly, to protect the right to privacy and personal data, the EU enacted the GDPR (European Union 2016). This piece of legislation seeks to protect fundamental rights recognized by the Charter, such as respect for private and family life (article 7) and the protection of personal data (article 8). The same protections can be found in article 16(1) of the TFEU. The main goal of the GDPR is to establish data protection principles and rules that must be followed by state authorities and private actors. Consequently, EU member states should update their existing national data protection laws based on the GDPR in order to harmonize their legal frameworks and ensure the free flow of personal data among different countries (FRA and CoE 2018: 29).

To implement democratic elections, electoral authorities must comply with the right to privacy and data protection in electoral contexts (Gross 2010: 5–6). These rights are part of a broader system of European values. Accordingly, these rights may be limited if it is necessary to achieve an objective of general interest. Limitations on data protection and the right to privacy should be evaluated case by case under specific circumstances. Based on article 52(1) of the Charter and article 23(1) of the GDPR, for instance, the implementation of free and fair elections might limit the exercise of the right to the protection of personal data through a proportionality test, which should:

- be carried out in accordance with the law;

- respect the essence of the fundamental right to data protection;

- be subject to the principles of proportionality, necessity and legitimate aim; and

- pursue an objective of general interest recognized by the EU (FRA and CoE 2018: 36).

Box 2.1. Overview of the GDPR: Key elements for elections

The GDPR upholds democracy and the rule of law by preventing the misuse of personal data, promoting transparency and ensuring accountability in electoral processes (European Commission n.d.b). These elements are particularly relevant in the context of digital political campaigns, where personal data is increasingly used for microtargeting voters, often leading to concerns over manipulation and privacy violations.

The GDPR establishes clear legal safeguards against the unlawful collection and processing of voter data, reinforcing citizens’ rights and electoral integrity. In an era where data-driven political campaigns and microtargeting have become prevalent, the GDPR serves as a crucial mechanism for ensuring that digital election strategies respect democratic principles and fundamental rights (Monteleone 2019).

By embedding strong data protection principles into the EU’s legal framework, the GDPR ensures that political actors, online platforms and electoral authorities operate in a transparent, fair and accountable manner. This legal safeguard protects electoral integrity, prevents undue influence in democratic decision making and reinforces the rule of law across the EU.

2.1.1. The application of GDPR principles in relation to elections

The use of technologies in the context of democratic elections relies on collecting, storing and analysing personal data. Voter registration, biometric identification technologies and electronic voting are examples of how the use of technologies is closely linked to the processing of personal data during elections. According to article 5 of the GDPR, electoral actors’ use of these technologies must comply with the following principles: (a) lawfulness, fairness and transparency; (b) purpose limitation; (c) data minimization; (d) data accuracy storage limitation; and (e) integrity and confidentiality.

These principles govern the processing of personal data. Any restrictions on or exemptions to these principles should be provided by law, pursue a legitimate aim and be necessary and proportionate in a democratic society (article

Hence, in the context of free and fair elections, the lawfulness of the processing of personal data by electoral actors should be based on one of three grounds: (a) a legal obligation; (b) the consent of the data subject; or (c) the necessity of performing a task in the public interest or in pursuit of a legitimate interest.

For instance, to make a reliable voter list in a specific electoral district, an electoral management body (EMB) must process voters’ personal data in order to implement the voter registration and authentication system. This processing of personal data could be permitted based either on freely, informed and unambiguous consent (article

2.1.2. The problem of consent

There are limitations to the processing of personal data under the GDPR. In the context of online political advertising, several actors have denounced the illusion of freely, informed and unambiguous consent needed under the GDPR. For instance, the new European regulation, the TTPA, cautions against ‘dark patterns’ that ‘materially distort or impair, either on purpose or in effect, the autonomous and informed decision-making of ... individuals’ (recital No. 75 TTPA). The European Data Protection Supervisor (EDPS) underscores the risks of leading users ‘into making unintended, unwilling and potentially harmful decisions regarding the processing of their personal data’ (European Data Protection Supervisor 2022: 2). In short, consent is being used to circumvent the GDPR and obtain huge amounts of personal data in the context of online political advertisements without meaningful knowledge on the part of the user.

When it comes to special categories of personal data such as political beliefs, ethnicity or sexual orientation, the processing of personal data is prohibited in principle (article 9 GDPR) unless explicit consent is given for data processing—or other legal grounds mentioned in article 9(2) of the GDPR apply. The TTPA applies the same criteria: the use of special categories of personal data is prohibited in the context of online political advertising, including in the context of using targeting and ad-delivery techniques employed by online publishers, unless the data subject’s consent is collected explicitly and separately for the purposes of political advertising (article 18 TTPA).

Reliance on consent to prevent the processing of sensitive data and the lack of mechanisms to prevent exploitation by private actors have had an enormous impact on online political advertising. The use of personal data in the context of online political advertising has transformed how voters are targeted and engaged. Thanks to behavioural targeting techniques, online political campaigns are using artificial intelligence (AI) systems to microtarget citizens on social media platforms with tailored political messages (Juneja 2024). Microtargeting entails the following:

- collecting data and dividing voters into segments based on characteristics such as personality traits, interests, background or previous voting behaviour;

- designing personalized political content for each segment; and

- using communications channels to reach the targeted voter segment with these tailor-made messages (International IDEA 2018).

These techniques can benefit both political parties and EMBs by expanding access to information for people who are not normally engaged in electoral processes. However, the same tools may also be used to manipulate citizens and undermine the public sphere by hindering public deliberation, accelerating political polarization and facilitating the spread of disinformation (Gorton 2016). The use of targeting techniques based on personal and sensitive data often takes place without users’ consent or clear understanding (Bashyakarla et al. 2019).

As mentioned earlier, given how platforms and the online advertising industry are using deception (such as so-called dark patterns) to obtain ‘consent’, these risks of manipulation, polarization and the spread of disinformation may affect the integrity of elections. At the same time, deceptive consent practices create vulnerabilities that malicious actors can exploit to disseminate disinformation and manipulative content.

2.1.3. Microtargeting and delivery techniques to reach voters: AI and automated decision making under the GDPR

The GDPR recognizes that automated decision-making processes—such as AI systems for profiling or online advertising delivery techniques—may have serious consequences. Thus, article 22 of the GDPR states that individuals have the right to not be subject to a decision based solely on automated processing (without human involvement in the decision process). However, the GDPR (article 22[1]) establishes that AI models can be trained on personal data if there is a specific lawful ground, such as consent, a contract or a legitimate interest. Furthermore, the GDPR also stipulates that citizens should be informed of the intention to train an AI model and be given the right to object or withdraw consent. Finally, individuals can appeal to the data controller for meaningful information about the logic behind the processing or to have an automated decision reviewed by a human.

Despite these rules, civil society organizations and scholars have highlighted the limitations of applying the GDPR to AI systems and the implications doing so has for individual rights. For instance, even though online platforms ensure that a certain category of personal data will not be collected, other data is collected and combined, revealing sensitive information about individuals, such as their political opinions, that social media companies, data brokers or third parties can infer. Additionally, given the very nature of deep machine-learning AI tools, data subjects (citizens) cannot possibly receive a meaningful explanation of how their personal data is processed, since these AI systems are inherently opaque and lack interpretability (Juneja 2024: 12; European Partnership for Democracy 2022: 5 ). Moreover, the fragmented and delayed application of the GDPR (Massé 2023: 3–4) makes it even more difficult to comply with GDPR principles such as data minimization and purpose limitation in the field of online campaigns.

2.1.4. Microtargeting and amplification techniques under the GDPR

As mentioned earlier, microtargeting techniques in online political campaigns target users based on an analysis of their personal and sensitive data to create highly tailored profiles based on their online behaviour (International IDEA 2018). Although microtargeting techniques may provide benefits for citizens by amplifying information around electoral processes, these techniques also pose several risks to rights and freedoms, such as manipulation or foreign interference (European Parliamentary Research Service 2019: 22). Microtargeting and amplification techniques not only reinforce polarization through the business models of big tech companies; they are also built upon an opaque structure that prevents authorities from monitoring compliance with data protection rules and from determining how money flows between publishers, social media companies, political parties and other actors (Heinmaa 2023: 15).

These business models rely heavily on engagement-driven algorithms, which tend to prioritize emotionally charged or divisive content—often referred to as ‘rage bait’—to maximize user attention and advertising revenue. This dynamic incentivizes the spread of polarizing narratives, deepening social divisions. The lack of transparency surrounding how content is promoted, who funds it and which users are targeted makes it nearly impossible to understand what information has been seen, by whom, under what conditions and as a result of what algorithmic decisions—undermining accountability and democratic oversight. One of the greatest challenges for electoral authorities is determining how to oversee online electoral campaigns when they are highly personalized and take place within an opaque system.

2.1.5. Limiting the use of special categories of personal data in electoral contexts

We have seen that there are both limitations and challenges in the application of the GDPR in the context of electoral processes.

In response to the significant challenges posed by the use of personal data in online political advertising—such as the lack of transparency, profiling based on sensitive information and potential manipulation of voter behaviour—the European Data Protection Supervisor has called for a prohibition on the collection and processing of special categories of personal data, including information about individuals’ health, sexual orientation and political affiliation (European Data Protection Supervisor 2022). This guidance reflects concerns that the GDPR alone may not adequately prevent the exploitation of sensitive data in political campaigning. Notably, this position aligns with the proposed provisions in article 18 of the TTPA, which seeks to impose stricter limits on the use of such data for targeting purposes in political contexts.

There is no justification in a democratic society for collecting and processing sensitive data for online political campaigns. The potential risks of microtargeting techniques, the underenforcement of the GDPR by electoral and data protection authorities, and the challenges surrounding consent under the GDPR are all arguments against allowing any exceptions for the use of special categories of personal data for the purposes of online political advertising.

In sum, the use of microtargeting techniques during elections has also revealed the limitations of enforcing GDPR rules in relation to online political advertising. Limiting the flow of personal data between private and public actors helps prevent infringements of fundamental rights that could undermine electoral processes. Ensuring the effective implementation of the GDPR in electoral contexts is one of the most important challenges for electoral authorities and policymakers.

Box 2.2. Hungary’s 2022 parliamentary election

A remarkable example of how the GDPR has functioned in the context of elections is the well-documented case of the 2022 parliamentary election in Hungary. A weak data protection framework, combined with a lack of enforcement by data protection authorities, contributed to abuses by authorities, political parties and private actors, enabling the deployment of illegal and deceptive online political campaigns. The OSCE ODIHR report (2022) highlighted practices of unlawful collection and misuse of personal data online. Such failures undermine the EU’s values and principles concerning elections, the rule of law and democracy.

Human Rights Watch (HRW) documented the use of sensitive personal data by the political party Fidesz and the Hungarian Government to conduct targeted political campaigns during the election. According to HRW (2022), ‘Evidence indicates that the government of Hungary has collaborated with the ruling party in the way it has used personal data in political campaigns.’

The lack of institutional independence in Hungary—particularly within the electoral authorities and data protection bodies—entailed privacy concerns (HRW 2022). The Civil Liberties Union for Europe (2022) expressed a similar concern: ‘where independent institutions are captured by the governing party, an EU-level enforcement mechanism is of key importance. It is unlikely that national watchdogs would enforce the regulation in a neutral, unbiased manner.’

Furthermore, the role of social media in the 2022 election revealed the limitations of GDPR enforcement and the challenges electoral authorities face when monitoring online political campaigns. The Civil Liberties Union for Europe (2022: 17–18) reported that social media platforms played a crucial role in developing personalized online campaigns that violated GDPR principles and rules. Publishers were able to target individuals based on sensitive characteristics—such as gender, sexual orientation or political affiliation—using tools like customer lists, custom audiences and lookalike audiences. However, there was no clear evidence that these campaigns obtained meaningful, free and informed consent from the individuals whose data was used. HRW (2022) made similar remarks, stating that the opaque nature of online platforms allowed political parties to target political advertising with little transparency.

HRW (2024) also reported that the government’s control over the media had severely affected journalistic independence and freedom of speech, directly impacting the electoral process. This systematic undermining of media freedom is a direct threat to fundamental rights, particularly those relating to freedom of expression and access to diverse viewpoints in electoral contexts.

The EU’s response to Hungary’s restrictions on media freedom included invoking mechanisms such as article 7 of the TEU to address systemic breaches of EU values, such as the rule of law, judicial independence and media pluralism.

Hungary’s case underscores the intersection of digital policy and electoral integrity, where control over the media—both traditional and online—poses significant risks to fair elections.

The lessons from Hungary’s 2022 election reinforce the critical need for a strong and independent regulatory framework to enforce data protection rules in electoral contexts. Such a framework should include the following measures:

- strict enforcement of GDPR principles and rules regarding the processing and transfer of personal data among public authorities;

- enhanced enforcement of GDPR provisions related to the use of sensitive personal data in online political campaigns; and

- stronger interagency collaboration between data protection authorities and electoral authorities to demand greater transparency and accountability from online platforms, which play a significant role in modern electoral campaigns.

2.1.6. Electoral authorities as controllers: Data protection impact assessments

In the context of elections, political parties, electoral authorities, individual candidates, civil society organizations (observers) and publishers, among others, may fall under the scope of the GDPR, meaning that public authorities have a legal obligation to process personal data and that other actors—such as political parties—must obtain consent or be able to demonstrate a legitimate interest (European Commission 2018: 5).

Whether based on a legal obligation, consent or public interest, electoral authorities and other actors must ensure that the use, collection and processing of personal data comply with the GDPR. As the CJEU has stated, actors involved in the collection and processing of personal data qualify as ‘controllers’ and therefore have obligations under data protection law.6 If a legal entity processes personal data only on behalf of and as instructed by the controller, it also falls under the GDPR. For instance, if an EMB asks a private company to prepare a biometric voter registration list, the processing of this biometric data by the electoral authority and the company must comply with the GDPR.

Compliance with GDPR standards touches upon the principles mentioned above—data minimization and purpose limitation, accountability, transparency, security and confidentiality, among others. These requirements mean that electoral authorities must put in place appropriate measures to mitigate data protection risks and implement privacy-by-design tools in the context of elections.

For instance, the GDPR states that, where processing is likely to result in a high risk to the rights and freedoms of individuals, controllers must carry out a prior assessment of the impact of the envisaged processing operation on the protection of personal data. Article 35 of the GDPR refers to this as a ‘data protection impact assessment’. These assessments should examine the specific impact of the intended processing on a data subject’s rights and determine whether the processing operation fulfils the proportionality test and complies with the above-mentioned principles.

Taking the same example of implementing a biometric voter registration list, a data protection impact assessment should comply with the above-mentioned principles and ask questions such as the following: Is this necessary for the performance of an election-related task (principle of necessity)? Is biometric data being processed fairly (principle of fairness)? Are data subjects informed about how their data is being used (principle of transparency)? Is the purpose of processing biometric data sufficiently specific and clear (principle of purpose limitation)? Is the processing of biometric data necessary, and could it not be reasonably fulfilled by other means (principle of storage and data minimization)? (For further details, see 3.3: Data processing by electoral management bodies.)

2.2. Cybersecurity in elections

Electoral authorities, in cooperation with other relevant institutions, are responsible for managing and mitigating risks—including cyberthreats—involved in organizing elections. In a democratic society, cybersecurity involves protecting the integrity of elections and ‘ensuring the transparent operation of a governance or election system’ (European Union Agency for Cybersecurity 2019: 4). Cyberthreats, such as attacks against the confidentiality, integrity and availability of election-related data or technologies during elections, could undermine electoral integrity (van der Staak and Wolf 2019).

Similarly, while often associated with disinformation, foreign information manipulation and interference (FIMI) also encompasses cybersecurity threats and cyberattacks targeting critical electoral infrastructure. Tactics, techniques and procedures used to exploit vulnerabilities highlight the need for a comprehensive approach to safeguarding election integrity. Hybrid threats such as FIMI, disinformation on social media, AI and deepfakes might also affect the integrity of electoral processes.

In the EU context, cybersecurity relates to protecting the integrity, availability and confidentiality of electoral processes based on an all-hazards, comprehensive and integrated approach. Although the organization of elections falls strictly within the competence of member states, the EU has developed several initiatives to address cyberthreats. Given the widespread use of digital technologies to support electoral processes, the promotion of cybersecurity across the EU plays an important role in safeguarding elections.

The NIS Cooperation Group, a collective effort of EU member states, the European Commission and the European Union Agency for Cybersecurity (ENISA), highlights the need for vigilance around elections because election technologies could be affected by ‘cyberattacks, system failures, human errors, natural disasters and similar contingencies such as power cuts and network outages’ (NIS Cooperation Group 2024: 4–5). This all-hazards approach has been outlined in a compendium on election cybersecurity written by the NIS Cooperation Group, which maps the main cyberthreats across the entire electoral cycle, including those targeting external actors such as political parties and politicians.

Given that human factors may impact cybersecurity during elections, EU initiatives have called for cooperation and knowledge sharing on online disinformation and hybrid threats such as FIMI. For instance, the European Cooperation Network on Elections has called for an exchange of information and good practices among member state networks to assess risks and identify cyberthreats and other incidents that could affect the integrity of elections (European Cooperation Network on Elections n.d.: 2). Similarly, the European Commission (2023: paragraph 20) has called for ensuring closer ‘cooperation between public and private entities involved in the cybersecurity of elections’ and for raising awareness of cyber hygiene among political parties, candidates, election officials and other entities related to elections.

Platforms for cooperation are particularly important due to the limited competences that the EU has on electoral issues, as these remain primarily with the member states. This division of responsibilities is grounded in articles 4 and 5 of the TEU, which provide that competences not conferred on the Union remain with the member states. As a result, electoral matters fall largely within the national domain, limiting the EU’s ability to legislate directly. Within the scope permitted by the Treaties, however, the EU plays a complementary role—facilitating coordination, supporting voluntary cooperation and encouraging the exchange of good practices through platforms that promote mutual learning and policy dialogue.

Examples of interagency cooperation include collaboration between the European Cooperation Network on Elections and the NIS Cooperation Group. Other initiatives to strengthen the resilience of electoral processes against cyberthreats include EU-CyCLONe (European Cyber Crisis Liaison Organisation Network), a cooperation network for the national authorities of member states responsible for cyber crisis management. Additional expertise across the EU could also help to tackle cyberthreats during elections through bodies such as the European Data Protection Board (EDPB), the European Union Agency for Cybersecurity, the Emergency Response Coordination Centre, Europol and networks of audiovisual regulators, among others (European Cooperation Network on Elections n.d.).

2.3. Platform regulation in Europe: An overview

Box 2.3. What is the DSA, and what are its main goals?

The DSA is an EU regulation adopted in 2022 that sets the legal standards for online content within the EU. The DSA plays a critical role in protecting democracy and electoral integrity by regulating the liability and responsibilities of online platforms and digital services. Through a set of fundamental principles and rules, it regulates the publication and distribution of online content by intermediary services such as online platforms (e.g. Facebook, Instagram or YouTube). It seeks to ensure that digital platforms operate transparently and responsibly while aligning with the fundamental rights outlined in the EU Treaties and the Charter.

The European Parliament highlighted the importance of upholding the values enshrined in article 2 of the TEU and emphasizes that fundamental rights—such as the protection of privacy and personal data, the principle of non-discrimination, and freedom of expression and information—must be ingrained at the core of a successful and durable EU policy on digital services (European Parliament 2020).

The DSA is primarily based on article 114 of the TFEU, which empowers the EU to adopt measures for the approximation of national laws that directly affect the establishment and functioning of the internal market. This legal basis enables the DSA to harmonize divergent national rules governing intermediary services—particularly in areas such as content moderation, online disinformation and illegal content—thereby ensuring the free movement of digital services across member states and preserving the integrity of the internal market.

Information integrity during elections is crucial for electoral processes, particularly in how (electoral) information flows in online contexts. In the EU, various legislative measures address this issue, notably the DSA (European Union 2022).

The DSA is a comprehensive legal framework designed to enhance transparency and digital safety by addressing the liability and accountability of various digital service providers, especially for digital platforms with more than 45 million users, including both search engines and social media platforms such as Facebook, Instagram and YouTube. On the one hand, the DSA aims to ensure fairness, trust and safety in the digital environment through a horizontal regulation that coexists with other specific legislation. On the other hand, the DSA stipulates obligations for digital service providers in order to prevent the dissemination of illegal or harmful content in online spaces, thus protecting the fundamental rights of citizens, the rule of law and democratic values.

Regulating content through the moderation decisions of private platforms falls within the field of fundamental rights and democratic issues. The power of digital service providers (private actors) to decide what content should remain online touches on constitutional matters concerning the regulation of freedom of expression and political speech. Under the DSA, ‘responsible and diligent behaviour by providers of intermediary services [is] essential for a safe, predictable and trustworthy online environment and for allowing Union citizens and other persons to exercise their fundamental rights, in particular the freedom of expression and of information’ (recital 3 of the DSA). Thus, the EU faces a complex challenge when it comes to regulating online platforms in order to protect, promote and reinforce the fundamental rights enshrined in the Charter as well as European values.

Although the DSA is the most important European legislation for addressing online harms, other EU laws also regulate information flow during elections. Rather than examining each piece of legislation individually, this section focuses on the principles and general rules governing content moderation in online spaces in order to safeguard fundamental rights and protect electoral integrity.

2.3.1. Challenges with online content moderation: The DSA and EU principles

The DSA follows three overarching principles developed during the 2000s by the Electronic Commerce Directive and the jurisprudence of the CJEU (Madiega 2022: 2):

- Country-of-origin principle (recital 38 of the DSA). Online service providers must comply with the law of the member states in which they are legally established.

- Limited liability regime (article 9 of the DSA). Online intermediaries are exempt from liability for the content they convey and host (users’ content) unless they have ‘actual knowledge’ (article 6 of the DSA) of illegal content or activity occurring on their platforms.

- Prohibition of general monitoring (article 8 of the DSA). Member states should refrain from imposing on online intermediaries a general obligation to monitor the information available through those online intermediaries.

These principles ensure that platforms are generally not liable for illegal activity or illegal content posted by users (limited liability principle). Additionally, they uphold users’ freedom of expression in online contexts, preventing private online platforms from monitoring and controlling content creation.

To give effect to these principles, the DSA takes a procedural approach. Rather than aiming to censor or determine which specific illegal content should remain online, it establishes specific procedures for identifying illegal or harmful content. This approach has been described as the ‘proceduralisation of intermediary responsibility’ (Busch and Mak 2021). Consequently, in line with the country-of-origin principle, member states have the freedom to define and regulate illegal content without hindering the implementation of the DSA’s core principles and rules. For example, electoral laws regulating online political campaigns can be aligned with the DSA framework and its approach to content moderation in the digital sphere.

The DSA adopts a layered approach, where obligations vary based on the type, impact and size of online intermediary services, which are categorized into three groups:

- Mere conduits. These are services that transmit information in a communication network (e.g. Internet access providers, DNS authorities, messaging apps).

- Catching services. These are services that provide automatic, intermediate and temporary storage of third-party information, such as content delivery networks.

- Hosting services. These are services that store information at the request of third parties—for example, search engines, social networks, content-sharing services, trading platforms, discussion forums, cloud services and app stores. This category includes both online platforms and very large online platforms.

In order to understand the interplay between the safety of online speech and electoral integrity, this report focuses mostly on very large online platforms (VLOPs) and very large online search engines (VLOSEs)—online intermediaries hosting services with more than 45 million monthly active recipients (users). These online services pose special risks when it comes to the dissemination of disinformation and illegal content. Examples of such services include online intermediaries such as Google (VLOSE), LinkedIn (VLOP), Facebook (VLOP), Instagram (VLOP), etc.

One of the DSA’s main goals is to address the dissemination of illegal content online and the societal risks posed by disinformation. To this end, intermediary services must include in their terms and conditions information about any restrictions they might impose in relation to the use of their services (article 14.1 DSA), such as content moderation policies, procedures, measures and automated tools (algorithms) used to implement and monitor their terms and conditions. For instance, Facebook’s terms and conditions prohibit the posting of nudity, and any nude content is filtered or removed by its algorithmic tools, as permitted by the DSA.

Any restrictions should pay due regard to the rights and legitimate interests of all parties involved, including the fundamental rights of the users, such as the freedom of expression, media freedom and pluralism, and other fundamental rights enshrined in the Charter.

Furthermore, the DSA mandates that all providers of hosting services and online platforms, regardless of their size, must implement notice-and-action mechanisms (article 16 DSA) that allow users to report specific pieces of information that may be considered illegal content. In other words, users must have the right to notify an online platform (e.g. Facebook) in a simple and user-friendly manner about illegal content (e.g. non-consensual sharing of intimate or manipulated material). These mechanisms must comply with the requirement to provide a statement of reasoning (article 17 DSA) and with other specific rules to protect the rights and legitimate interests of all affected parties, particularly their fundamental rights guaranteed in the Charter.

2.3.2. Content moderation addressing online gender-based violence

The same DSA principles and rules apply to the EU Directive on Combating Violence against Women and Domestic Violence (European Union 2024c), particularly regarding orders and other measures requiring the removal of or disabling of access to material that may depict online gender-based violence. The removal or restriction of access to such material, when it constitutes a criminal offence, should be carried out in a transparent manner and with adequate safeguards. The relevant criminal offences include the following:

- non-consensual sharing of intimate or manipulated material (article 5), which includes deepfakes that alter audiovisual material to make it appear as if a person is engaged in sexually explicit activities without that person’s consent;

- cyber harassment (article 7), which involves engaging in publicly accessible threatening or insulting conduct that causes serious psychological harm to a person, or making a person’s personal data publicly accessible without that person’s consent; and

- cyber incitement to violence or hatred (article 8), such as inciting violence or hatred against a group of persons or a member of such a group, defined by reference to gender, by publicly disseminating such content by means of ICTs.

In the context of electoral processes, these offences are regarded as aggravating circumstances wherever an offence is committed by abusing a recognized position of trust, authority or influence (article 11[m] of the Directive) or if an offence is committed against a person because that person is a public representative (for instance, women politicians).

In the context of this Directive, the ‘competent authorities’ who are empowered to order the removal or disabling of harmful material are those designated under national law as competent to carry out the duties provided for in this Directive (recital 14). Accordingly, only national electoral law can confer on electoral authorities the power to order the removal or disabling of access to the above-mentioned harmful material in the context of electoral processes.

2.3.3. The role of media in electoral democratic processes: Moderating online media content

An exception to the general rules on content moderation in the EU concerns how online media content is moderated by VLOPs under the EMFA (European Union 2024b). The EMFA is a vertical regulation that should be applied directly to member states alongside the DSA. According to article 18(4), a VLOP may not suspend or restrict the visibility of content from a self-declared media service provider (such as The Guardian, The New York Times or France 24) except by following a special procedure outlined in the regulation. This rule acknowledges the importance of press freedom, media plurality and journalism as essential democratic institutions that guarantee citizens access to reliable news.

These fundamental rights apply even more in electoral contexts. For this reason, the EU legislator believes that self-declared media service providers should not be unilaterally silenced by VLOPs based exclusively on their terms and conditions or other specific legal grounds (Nenadić and Brodgi 2023).

Before a VLOP restricts or suspends content that might contain disinformation under its terms and conditions, it must provide a statement explaining the decision and give the media service provider 24 hours to respond. During this period, the VLOP may neither remove nor restrict the content.

It is important to highlight that this provision does not apply to illegal content pursuant to EU law such as hate speech or non-consensual intimate or manipulated material. Thus, specific illegal content posted by media service providers is subject to DSA rules and the terms and conditions of online platforms. VLOPs should follow article 9 of the DSA and remove illegal content based on orders issued by the relevant judicial or administrative authorities, put in place notice-and-action mechanisms, inform competent national enforcement or judicial authorities if they become aware of a criminal offence on their platforms, and suspend users who misuse their services by providing manifestly illegal content (article 23 and recital 62 of the DSA). Finally, VLOPs should also follow the risk assessment and mitigation risk obligations to protect against illegal content (Nenadić and Brodgi 2023).

Box 2.4. The EMFA in brief: Ensuring a free and fair media landscape in the EU

The EMFA reinforces the protection of media pluralism, editorial independence and the safety of journalists. Anchored in the principles of democracy, the rule of law and fundamental rights, the EMFA builds upon article 11 of the Charter, which guarantees freedom of expression and information, as well as article 2 of the TEU, which enshrines democracy as a core EU value.

The EMFA complements existing EU legislation, such as the DSA and GDPR, by addressing challenges posed by increasing digitalization, political interference and economic pressures on media independence. By setting clear safeguards against the misuse of surveillance tools, undue state influence and opaque ownership structures, the EMFA ensures that journalism remains free from interference and that citizens have access to reliable, diverse and independent information.

By preventing political and economic pressures on media outlets, strengthening safeguards against spyware abuses, and enhancing transparency in media ownership and funding, the EMFA upholds press freedom as an essential pillar of democracy. In conjunction with the DSA and the GDPR, the EMFA contributes to a resilient and fair digital information ecosystem, ensuring that fundamental rights remain protected in an increasingly digitalized media landscape.

2.3.4. Due diligence obligations under the DSA: Risk assessment and mitigation measures

As mentioned earlier, the DSA establishes a layered set of obligations based on the type, impact and size of online intermediaries. VLOPs and VLOSEs represent the largest category of online intermediaries and are therefore subject to special obligations. These corporations and their obligations fall under the competence of the European Commission.

One of the most important obligations for VLOPs and VLOSEs is to diligently identify, analyse and assess any systemic risks arising from the design or functioning of their services, including algorithmic systems, as specified in article 34 of the DSA. In other words, platforms must conduct their own assessments of systemic risks, which include the following:

- the dissemination of illegal content through their services;

- any actual or foreseeable negative effects for the exercise of fundamental rights, including freedom of expression, media pluralism, and the right to vote and to stand as a candidate at elections;

- any actual or foreseeable negative effect on civic discourse and electoral processes; and

- any actual or foreseeable negative effects in relation to gender-based violence.

The identification of these systemic risks will entail putting in place reasonable, proportionate and effective mitigation measures, set out in reports that identify and assess the most prominent and recurring risks. In addition, these reports should include best practices for VLOPs and VLOSEs to mitigate these systemic risks. The reports must be broken down by member state and, upon request, submitted to the relevant digital services coordinator as well as the European Commission (article 34[3] DSA).

Some of the actual and foreseeable risks include a lack of diversity and meaningful sources in online contexts, manipulation through micro- and nanotargeting techniques, misidentification of political advertising, radicalization and polarization of online spaces, disinformation, the spread of hate speech, and censorship by politicians or political candidates, among other things (Reich and Calabrese 2025).

Box 2.5. The DSA as a safeguard for electoral integrity: The case of Romania

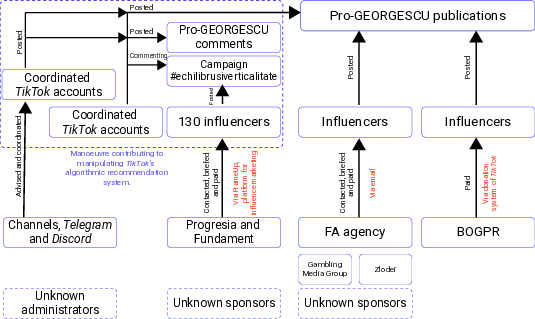

On 24 November 2024 the far-right extremist candidate Călin Georgescu received the most votes in the first round of the Romanian presidential election. Despite running with no campaign budget, he secured almost 23 per cent of the vote (around 2 million votes) by campaigning almost exclusively online, mainly on TikTok.

Other presidential candidates subsequently filed judicial complaints. In addition, several reports from Romania’s intelligence agencies documented the use of voter manipulation techniques via social media platforms, cyberattacks, Russian electoral interference and illegal online practices. On 6 December 2024, taking these elements into consideration, the Constitutional Court of Romania decided to annul the elections ex officio.

Multiple irregularities exposed by several authorities revealed manipulation of the vote and violations of the principles of transparency and of the free and fair conduct of elections, including the non-transparent use of digital technologies and AI in the campaign, as well as the financing of the campaign from undeclared sources, both in violation of electoral legislation and undermining the principle of equal opportunity among electoral competitors (Venice Commission 2025). Ultimately, these breaches ‘distorted the free and fair nature of the vote, compromised electoral transparency, and disregarded legal provisions on campaign financing’ (Barata and Lazăr 2025).

Regarding the alleged manipulation of voting through social media, the European Digital Media Observatory reported that the number of followers on Georgescu’s account tripled between 10 and 24 November 2024 (Botan 2024). An astroturfing campaign, coordinated through thousands of TikTok accounts and a network of paid influencers, exploited TikTok’s recommender systems to artificially boost the visibility of Georgescu’s messages. Nevertheless, the presidential candidate declared no expenses at all (Cornea 2025). As a result of this online strategy, hashtags related to Georgescu’s campaign reached ninth place in TikTok’s global ranking (VIGINUM 2025: 7).

All these mechanisms to artificially increase the visibility of TikTok accounts are prohibited under the platform’s terms and conditions. However, the campaign’s use of bots and influencers to exploit the algorithms is not illegal under either the DSA or the TTPA (for an overview of the manoeuvres taken by the candidate, see Figure 2.1).

The European Commission opened a formal proceeding against TikTok under the DSA, requesting information regarding the actions the platform had taken to reduce potential algorithmic bias during the electoral process. In other words, TikTok was asked to provide details on the measures it took regarding the ‘management of risks to elections or civic discourse’ linked to its recommender systems, notably the risks ‘linked to the coordinated inauthentic manipulation or automated exploitation of the service’, as well as its policies on political advertisements and paid political content (European Commission 2024e).

This case shows that it is difficult to foresee the type and impact of measures that the European Commission may take against platforms, particularly since it is the companies themselves that decide how to address systemic risks on their platforms in electoral processes. Even though the Commission has issued guidelines on safeguarding online electoral integrity, these measures are not legally binding. Consequently, their implementation differs from one company to another. Moreover, civil society organizations have pointed out that ‘the guidelines do not contain benchmarks by which the success or failure of the suggested measures can be evaluated’ (Alvarado Rincón 2025). Other experts have highlighted that the case has shown that ‘certain forms of (allegedly paid) political messaging became almost impossible to tackle when included as short mentions in long influencer videos mainly focusing on make-up trends’ (Barata and Lazăr 2025).

This case illustrates how easily deceptive actors can exploit VLOPs’ algorithmic recommender systems to manipulate electoral processes. It also underscores the responsibility of online social media platforms to ensure a safe online environment in the context of elections. Furthermore, it highlights the need for the European Commission to work hand in hand with EMBs and other national actors to monitor such developments in order to prevent breaches of European values, including the conduct of free, fair and transparent elections.

2.4. Online political advertising: Towards harmonized European regulation

The DSA treats online political advertising as a form of online advertising and content. This means that online political advertising must comply with both the general rules governing online advertising and the DSA’s content moderation rules (e.g. terms and conditions, notice-and-action mechanisms, trusted flaggers, systemic risk assessments, etc.).

Article 3(r) of the DSA defines advertising as:

information designed to promote the message of a legal or natural person, irrespective of whether to achieve commercial or non-commercial purposes and presented by an online platform on its online interface against remuneration specifically for promoting that information.

The two key elements of this definition are as follows:

- It explicitly includes ‘non-commercial purposes’ (e.g. political content).

- It requires that content be promoted ‘against remuneration’.

Hence, organic political content (unpaid content and information flows driven by algorithmic recommender systems) does not fall within the scope of online advertising under the DSA.

Conversely, organic political content could fall under the new European regulation, the TTPA (European Union 2024a). The TTPA’s definition of political advertising includes content that is ‘normally provided for remuneration’ (article 3[2]). In other words, unpaid political speech could still fall under this regulation, raising concerns about potential restrictions on freedom of expression and political speech in online spaces (ARTICLE 19 2023; Heinmaa 2023).

This regulatory overlap may affect the enforcement of the DSA, given the contradictions between the two legal frameworks. It could also create coordination problems among electoral authorities, digital services coordinators and other regulatory bodies (such as media authorities), all of which may have an interest in enforcing the EU’s online political advertising regulations (Heinmaa 2023).

As mentioned earlier (see 2.1.5. section), the DSA requires that online advertising provided by VLOPs and VLOSEs must not be displayed based on profiling that uses special categories of personal data (such as political opinion, sexual orientation or ethnic origin). This rule impacts the targeting and ad-delivery techniques that publishers use to identify the most precise audiences for online political advertising. However, the rule has not had the intended impact. Due to the mechanisms used by big tech companies to monitor, extract and collect behavioural data, targeted advertising that does not rely on profiling or does not use special categories of data in the context of profiling may still be allowed (Duivenvoorde and Goanta 2023: 9–10).

Targeting and ad-delivery techniques involve the collection of personal data, including observed and inferred data (but not sensitive data), which may nonetheless reveal sensitive aspects concerning citizens (Becker Castellaro and Penfrat 2022). Moreover, under both the DSA and the TTPA, as well as the Code of Conduct on Disinformation, the explicit consent of a data subject to process their personal data specifically for the purpose of political advertising creates an exception to this prohibition (European Commission 2025c).

Several civil society organizations, along with the European Data Protection Board, the Committee on the Internal Market and Consumer Protection of the European Parliament (2023) and Juneja (2024), have recommended a total ban on microtargeting techniques that use special categories of sensitive data for political purposes. This recommendation aims to mitigate the risks of polarization, the creation of echo chambers and the spread of disinformation associated with targeting and ad-delivery techniques (Becker Castellaro and Penfrat 2022).

However, this prohibition has not been incorporated into either the DSA or the TTPA.

Box 2.6. Regulation on the transparency and targeting of political advertising: Ensuring fair and transparent digital political campaigning in the EU

Grounded in article 7 (respect for private and family life), article 8 (protection of personal data) and article 11 (freedom of expression and information) of the Charter, as well as article 2 of the TEU, which enshrines democracy as a core EU value, the TTPA aims to prevent manipulation, ensure transparency and safeguard electoral integrity in the digital age (European Commission n.d.a).

In line with article 16 of the TFEU, which guarantees the protection of personal data, and article 8 of the Charter, which enshrines data protection as a fundamental right, the TTPA complements the GDPR by limiting the unlawful use of personal data in political advertising. It establishes safeguards against the exploitation of sensitive data, the misuse of AI-driven microtargeting techniques and opaque algorithmic amplification of political messages.

Furthermore, the TTPA complements the DSA by imposing stricter accountability measures on online platforms and ad providers, ensuring that political ads are clearly labelled, traceable and accessible for public scrutiny. This regulatory approach prevents undue influence in democratic processes, strengthens electoral integrity and enhances transparency in digital political campaigning.

By combating disinformation, preventing data-driven voter manipulation and ensuring fairness in digital political discourse, the TTPA helps safeguard democratic principles and fundamental rights in the digital era (Rabitsch and Calabrese 2024: 7).

2.4.1. Transparency on political advertising

Transparency and reliable data on online political advertising are crucial for evaluating the accountability of online platforms in their fight against disinformation. Some transparency requirements are already included in the DSA and the Code of Conduct on Disinformation, including user-facing transparency commitments, ad repositories, engagement with civil society organizations, and monitoring and research based on online platform data (European Commission 2025c).

Various regulations in the European legal framework, including the Code of Conduct on Disinformation, serve as legal sources of measures and obligations for ensuring transparency in online political advertising. The objective of all these legislative instruments is to enable citizens to easily recognize political advertising.

Among these legal sources, the TTPA is the most important regulation for understanding the transparency measures that online platforms must implement regarding online political advertising. Under article 8 of the TTPA, the identification of a political advertisement should include the following elements: (a) the content of the message; (b) the sponsor of the message; (c) the language used to convey the message; (d) the context in which the message is conveyed, including the period of dissemination; (e) the means by which the message is prepared, placed, promoted, published, delivered or disseminated; (f) the target audience; and (g) the objective of the message.

Based on article 7 of the TTPA, sponsors (e.g. politicians or political parties) must declare whether an advertisement constitutes a political ad, and service providers (e.g. a VLOP or VLOSEs) must request the necessary information to comply with the regulation once such a declaration is made by the sponsor. In other words, the obligation to declare an advertisement as political rests with the sponsors. Civil society organizations have warned, however, that transparency obligations could be circumvented by both sponsors and online platforms if they simply fail to indicate ‘that the ads that they are running are political’ (Calabrese 2024a: 3).

In addition, the TTPA establishes a European repository for online political advertisements that should be put in place by the European Commission. This public repository is intended to publish all online political advertisements deployed in the European Union. The information should be available in a machine-readable format and publicly accessible via a single portal. The repository should include transparency notices for political advertising, including the following information (article 12[1)] TTPA):

(a) the identity of the sponsor and, where applicable, of the entity ultimately controlling the sponsor, including their name, email address, and, where made public, their postal address, and, when the sponsor is not a natural person, the address where it has its place of establishment;

(b) the information required under point (a) on the natural or legal person that provides remuneration in exchange for the political advertisement if this person is different from the sponsor or the entity ultimately controlling the sponsor;

(c) the period during which the political advertisement is intended to be published, delivered or disseminated;

(d) the aggregated amounts and the aggregated value of other benefits received by the providers of political advertising services, including those received by the publisher in part or full exchange for the political advertising services, and, where relevant, of the political advertising campaign;

(e) information on public or private origin of the amounts and other benefits referred to in point (d) as well as whether they originate from inside or outside the Union;

(f) the methodology used for the calculation of the amounts and value referred to in point (d);

(g) where applicable, an indication of elections or referendums and legislative or regulatory processes with which the political advertisement is linked;

(h) where the political advertisement is linked to specific elections or referendums, links to official information about the modalities for participation in the election or referendum concerned;

(i) where applicable, links to the European repository for online political advertisements referred to in Article 13;

(j) information on the mechanisms referred to in Article 15(1);

(k) where applicable, whether a previous publication of the political advertisement or of an earlier version of it has been suspended or discontinued due to an infringement of this Regulation;

(l) where applicable, a statement to the effect that the political advertisement has been subject to targeting techniques or ad-delivery techniques on the basis of the use of personal data, including information specified in Article 19(1), points (c) and (e);

(m) where applicable and technically feasible, the reach of the political advertisement in terms of the number of views and of engagements with the political advertisement.

The TTPA establishes specific functions for electoral authorities to ensure compliance. According to article 16, electoral authorities (‘national competent authorities’) may request that providers of political advertising services (such as VLOPs and VLOSEs) transmit any required information mentioned above. The deadline for complying with these rules range from 2 to 12 days, depending on the size of the company involved. In the last month preceding an election or a referendum, providers of political advertising services must provide the requested information within 48 hours.

In addition, each provider of political advertising services, including VLOPs and VLOSEs, must designate a contact point for communication with the competent national authorities. The above-mentioned data could also be shared with vetted researchers, civil society organizations, political actors, national or international observers and journalists.

2.4.2. Data access for researchers: DSA and TTPA examples

The DSA covers third-party scrutiny and research (data access). According to the European Commission (2024c), ‘Stable and reliable data access for third-party scrutiny is of utmost importance during electoral periods to ensure transparency, advance insights and contribute to the further development of risk mitigation measures around elections.’ In addition to their legal obligations under article 40 of the DSA, the Commission recommends that VLOPs and VLOSEs provide free access to data to study risks related to electoral processes, including scrutinizing AI models, visual dashboards and other additional data points.

Data access is essential for establishing checks and balances on how online platforms comply with the DSA and the TTPA and, ultimately, in combating illegal content and disinformation. Such access permits vetted researchers to assess systemic risks to electoral processes and civic discourse (such as FIMI, disinformation and the spread of hate speech, among other things) and to develop evidence-based online policies to mitigate those risks (see 3.4.1: The role of EMBs in risk assessment and mitigation under the DSA: Due diligence obligations of VLOPs and VLOSEs in electoral processes).

Furthermore, member states must designate a national competent authority responsible for keeping publicly available and machine-readable online registers of all legal representatives registered on their territory under the TTPA. Each national competent authority is required to ensure that such information is easily accessible and that it is complete and regularly updated (article 22 TTPA). The TTPA establishes a closed list of powers, granting national competent authorities the power to do the following:

(a) request access to data, documents or any necessary information, in particular from the sponsor or the providers of political advertising services concerned, which the competent authorities are to use only for the purpose of monitoring and assessing compliance with this Regulation, in accordance with relevant legislation on the protection of personal data and the protection of confidential information;

(b) issue warnings addressed to the providers of political advertising services regarding their non-compliance with the obligations under this Regulation;

(c) order the cessation of infringements and require sponsors or providers of political advertising services to take the steps necessary to comply with this Regulation;

(d) impose or request the imposition by a judicial authority of fines or financial penalties or other financial measures as appropriate;

(e) where appropriate, impose a periodic penalty payment, or request a judicial authority in their Member State to do so;

(f) where appropriate, impose remedies that are proportionate to the infringement and necessary to bring it effectively to an end or request a judicial authority in their Member State to do so;

(g) publish a statement which identifies the legal and natural person(s) responsible for the infringement of an obligation laid down in this Regulation and the nature of that infringement;

(h) carry out, or request a judicial authority to order or authorise, inspections of any premises that providers of political advertising services use for purposes related to their trade, business, craft or profession, or request other public authorities to do so, in order to examine, seize, take or obtain copies or extracts of information in any form, irrespective of the storage medium.

The TTPA also emphasizes the importance of holding a ‘regular exchange of information’ among the national contacts designated by member states, along with sharing best practices and promoting cooperation between national authorities and the European Commission in all aspects of its implementation. This cooperation should include collaboration with the European Cooperation Network on Elections, the European Regulators Group for Audiovisual Media Services, and other relevant networks or bodies. Additionally, national authorities may also cooperate with other national stakeholders to support implementation and compliance with the TTPA.