Managing elections to withstand natural hazards in Peru

Elections and Natural Hazards Series

Executive summary

This study analyses Peru’s increasing vulnerability to extreme natural phenomena and its efforts in response, specifically regarding elections. Highlighted by the World Risk Report 2024, Peru ranks 11th globally in terms of disaster risk, with structural vulnerabilities exacerbated by climate change (Bündnis Entwicklung Hilft/IFHV 2024). Events such as El Niño, landslides and floods pose significant threats to the infrastructure necessary for conducting elections, potentially hindering access to polling places and affecting citizen participation. The research focused on actions taken by the National Office of Electoral Processes (ONPE) during the 2022 regional and municipal elections to mitigate the impact of natural hazards at all stages of the electoral process.

Employing a qualitative methodology, this study examines strategic decision-making, challenges faced and lessons learned in risk management. Activities included a review of documentation and semi-structured interviews with key personnel from the ONPE (see Annex A). Findings indicate that, although the ONPE did not implement a specific disaster management plan, it possesses specific pathways and tools to address emergencies; these include a risk matrix, training for electoral personnel and means of establishing accessible polling places nationwide.

The ONPE successfully organized the 2022 regional and municipal elections—all 84,323 polling stations were installed and operational and the potential risks were identified. Proactive planning involved assessing various risk situations. The ONPE implemented measures such as the Elige tu Local de Votación (Choose your Polling Station) platform, allowing voters to select polling places close to their residences for enhanced accessibility, especially in remote areas.

The study also identifies areas for improvement, including the need for a comprehensive contingency plan for future elections and the hiring of dedicated personnel for distribution and collection of electoral materials. The introduction of an early warning and response system known as Electoral Conflict Alert Map (MACE) will facilitate the reporting of incidents during elections. Ultimately, enhancing electoral management bodies’ (EMBs) organizational structures and establishing a dedicated security and defence office will reinforce the ONPE’s capacity to manage risks associated with natural hazards effectively, ensuring continued electoral integrity under challenging conditions.

Introduction

Peru faces an increasing risk from extreme natural phenomena, a situation exacerbated by the effects of climate change (Córdova Aguilar 2020). According to the World Risk Report 2024, Peru ranks 11th globally and 3rd in Latin America in terms of the risk of natural hazards (Bündnis Entwicklung Hilft/IFHV 2024). This risk arises not only from the likelihood of hazards occurring but also from conditions of structural vulnerability (IADB 2015). In this context, the World Risk Report classifies Peru as having ‘very high’ vulnerability and ‘very high’ lack of coping capacities—an indicator which encompasses social shocks, political stability, health services, infrastructure and material security, among others (Bündnis Entwicklung Hilft/IFHV 2024).

Events such as El Niño, landslides, floods and earthquakes have repeatedly disrupted the normalcy of the country by affecting infrastructure, paralysing communication routes and resulting in the suspension of essential services. The increasing vulnerability to natural hazards also has the potential to significantly impact the electoral process, as these can hinder access to polling places, delay the transport of electoral materials and compromise citizen participation (Asplund, Fischer and Birch 2022). Additionally, they can negatively affect the credibility of elections (Darnolf 2018).

Given that natural hazards are becoming increasingly unpredictable, response times are considerably shortened. It has been argued that electoral bodies must adopt a proactive approach and optimize use of limited resources by (a) coordinating with other state and local authorities through structures of advance disaster planning; and (b) reviewing and updating contingency plans on a regular basis (Darnolf 2018).

In this regard, early identification of at-risk electoral districts and the implementation of (inter-agency) preventive measures are crucial. This case study focuses on the actions taken by Peru’s National Office of Electoral Processes (ONPE) during the regional and municipal elections (ERM) of 2 October 2022, with the aim of evaluating EMBs’ capacity to mitigate natural hazard impacts at all stages of the electoral process.

The Peruvian case is particularly relevant due to the country’s institutional framework, which delegates electoral responsibilities to three autonomous and independent bodies: the ONPE, the National Jury of Elections (JNE) and the National Registry of Identification and Civil Status (RENIEC). Among these, the ONPE is specifically tasked with organizing and executing electoral processes and popular consultations (referendums), as established in article 5 of the Organic Electoral Law (Peru 1995). This mandate is further specified in the ONPE’s Organization and Functions Regulation (ROF), which outlines the responsibilities of its operational bodies (ONPE 2024). Given this institutional role, analysing the ONPE’s response during the 2022 elections offers valuable insight into how EMBs can adapt to environmental risks and ensure electoral integrity in hazard-prone regions.

1. Risk of natural hazards in Peru

Peru is located along the Pacific Ring of Fire, which exposes it to high seismic activity and a variety of natural hazards. In recent decades, the country has faced major weather/environmental events that have tested its response capacity and risk management systems. These include the Pisco earthquake in 2007, the Coastal El Niño in 2017, the sewage flooding in San Juan de Lurigancho in 2019 and, more recently, the effects of Cyclone Yaku in 2023.

Beyond these high-impact events, between 2003 and 2022 the country recorded over 99,683 emergencies. Recurrent hazards include heavy rains, urban and industrial fires, low temperatures, strong winds and floods, accounting for 84.4 per cent of all recorded incidents (INDECI 2023). However, the frequency of these hazards does not necessarily correlate with severity of impact. For instance, although heavy rains are the most frequent, low temperatures have caused the greatest harm to the population.

During the electoral year 2022 between January and October, the National Centre for Estimation, Prevention, and Disaster Risk Reduction (CENEPRED) issued 51 reports on risk scenarios due to rainfall, 49 related to low temperatures and 10 on forest fires. The rainfall and low temperature risk reports were based on meteorological alerts provided by the National Meteorology and Hydrology Service (SENAMHI). These reports, relayed by the National Institute of Civil Defence (INDECI), primarily focused on the Sierra (the Andes) and Selva (the jungle) regions of the country.

In the week of the electoral process two reports were issued, both related to risk scenarios due to rainfall. Between 30 September and 2 October 2022, the SENAMHI forecasted moderate to heavy rainfall in the Sierra, including snow, hail, sleet and rain.1 In response, the CENEPRED identified 101 districts out of 1,874 at ‘very high’ risk of mass movements: in the departments of Áncash, Huancavelica, Huánuco, Pasco, Junín and Lima. Within these districts 2,430 educational institutions were exposed to risk. Additionally, 133 districts in the same departments were classified as having a ‘high’ risk, with 2,710 educational institutions identified as potentially vulnerable (CENEPRED 2022a).

In the Selva region, between 29 September and 1 October, the SENAMHI forecasted moderate to heavy rainfall, accompanied by lightning and gusts of wind.2 Regarding the risk of mass movements, the CENEPRED identified 15 districts in the departments of San Martín and Loreto with a ‘very high’ risk, affecting 111,358 people, 27,603 households, 83 health facilities and 582 educational institutions. Additionally, 58 districts at ‘high’ risk were identified in San Martín, Huánuco, Loreto and Ucayali, with 750,843 inhabitants, 192,339 households, 387 health facilities and 2,240 educational institutions between them (CENEPRED 2022b).

Since a significant portion of Peru’s polling places are educational institutions (Peru 2019: article 65), damage to them has implications for elections. For example, in the ERM 2022, monitoring conducted by the Office of the Ombudsman—on election day and the day prior—identified that 4.7 per cent (99) of the 2,078 supervised polling places were affected by at least one natural hazard (Defensoría del Pueblo 2022). The departments of Lima and Ayacucho accounted for 30 per cent of those damaged (19 and 11 polling places, respectively) (Defensoría del Pueblo 2022).

The day after polling (3 October), the ONPE conducted a virtual survey targeting two specific groups: District Coordinators (CDIST), responsible for the administration at the district level, and Rural Population Centre Coordinators (CCP), in charge of rural jurisdictions within districts.3 These groups were selected to ensure a more accurate representation of issues at the district level. A total of 2,384 surveys were sent to CDIST personnel, with 682 responses received (28 per cent), while 371 out of 1,349 CCP representatives responded (29 per cent).

The survey responses were used to identify and understand problems that affected election day operations. One of the key findings was the presence of weather-related issues: 12.9 per cent of respondents reported that rainfall or floods occurred and affected the staff’s duties during the electoral process. The most affected regions in terms of the proportion of impacted jurisdictions were Huánuco (12), Amazonas (8) and Ayacucho (11). Extreme weather events thus posed some logistical challenges to electoral processes in several parts of the country.

More generally, natural hazards can do so by complicating access to polling locations, delaying the transportation of electoral materials (such as ballots, ballot boxes and booths, voter registration/voter counting and other records), and negatively affecting the participation of both voters and electoral personnel. During the ERM 2022 no emergencies caused by natural hazards were recorded. Nevertheless, districts with very high or high risk of disasters during the week of the elections were systematically identified, as well as polling places that had sustained damage from rainfall, landslides and earthquakes. All polling stations were properly established (ONPE 2023) and citizens were able to exercise their right to vote. The measures adopted by the ONPE to ensure this successful outcome are detailed in a subsequent section (3. The 2022 Regional and Municipal Elections).

2. Impacts of natural hazards on previous elections

There are no available records that detail cases of natural hazards affecting the ONPE’s efforts to set up polling stations or open polling locations to the public. However, fieldwork identified two cases in different electoral processes where natural hazards prevented the installation of polling stations or prompted their relocation. It is important to note that the information collected comes from the statements of interviewed individuals and reflects their best recollection of the events.

The first case occurred during the 2010 second regional election in the district of Oronccoy, located in La Mar Province, Ayacucho Department. According to the information provided, this district is situated high in the Andes at 3,394 metres above sea level. Due to difficulty of access, the electoral materials were made ready early and transported by air with the support of a military helicopter.

On that occasion, the rains did not cease during the entire week before the election. ONPE personnel, along with the armed forces, safeguarded the electoral materials at the Pichari Military Base, located in La Convención Province, Cusco, a jurisdiction adjacent to the district of Oronccoy. It was expected that the helicopter would depart from the base once the rains stopped. Departure was attempted on the Wednesday and Thursday, but the weather prevented it. Although the helicopter managed to take off on three subsequent days, it could not land in Oronccoy because of the rain—the Armed Forces stated that they were unwilling to take this risk with the lives of their personnel or the ONPE and JNE personnel traveling with them. As a result, polling stations were not set up in the district of Oronccoy. It is estimated that the right to vote of approximately 600 people was affected, involving two polling stations.

The second case occurred during the 2016 general elections. In this case, the interviewee could not determine whether it occurred in Alto Amazonas Province or Maynas Province, both located in Loreto Department, in the Peruvian jungle.

Due to heavy rains many structures in the jungle are built on elevated platforms to allow water to pass underneath without damaging them. As mentioned, polling locations are mostly situated in educational institutions, many of which have the elevated structure described.

The day before polling, the Head of the Decentralized Office of Electoral Processes (ODPE—ONPE’s offices operating at the subnational level) responsible for the area noticed that one such school designated as a polling location was surrounded by rainwater. Although the structure itself was not affected due to its elevation, accessing it became dangerous for voters and staff. For this reason, it was decided to relocate the polling location to another nearby school. This involved moving both personnel and electoral materials hours before the election started.

According to the interviewee, this decision was made so quickly that the Electoral Organization and Regional Coordination Management was not promptly informed and it was later documented in a JNE oversight report. Nevertheless, this urgent action allowed voters to cast their votes and contributed to the success of election day in the locality.

The experiences mentioned illustrate that hazard situations impacting the electoral process are not always recorded, and much depends on the staff coordinating to resolve them in real time. Unfortunately, in some cases, resolution is not possible. However, considering that more than 80,000 polling stations are set up nationwide, the incidence of such situations is minimal, and the capacity of ONPE personnel to resolve difficulties has to date been generally sufficient.

3. The 2022 Regional and Municipal Elections

3.1. Context and regulatory framework

It is important to first clarify the broader context and the regulatory framework that shaped this electoral process. First, according to the Law of Regional Elections (Law No. 27683, article 2) and the Law of Municipal Elections (Law No. 26864, article 1) these contests are held every four years in a single process. In regional elections, citizens elect regional authorities, including the governor, deputy governor and regional councillors. The relevant constituencies correspond to the 24 departments and the Constitutional Province of Callao. In municipal elections, citizens elect mayors and councillors, who serve on municipal councils. For the election of provincial municipal councils, each province in the country constitutes a single electoral constituency; for the election of district municipal councils, each district within a province forms its own electoral constituency.

For 2022, the electoral process was called for 2 October. During this electoral process, at the regional level, 25 governors, 25 deputy governors and 342 regional councillors were elected. At the provincial level, 196 provincial mayors and 1,714 provincial councillors were elected. Finally, at the district level, 1,694 district mayors and 9,036 district councillors were elected (ONPE 2022b).

Nationwide, just over 24.75 million voters (24,760,062) were registered on the electoral roll. To ensure a smooth and accessible voting process, 11,298 polling places were established, at which 84,323 polling stations were set up. Of this total, 3,890 polling stations, corresponding to 1,341 polling places, were located in centros poblados—small villages with low populations located in rural areas, far from the provincial capitals. (Access to these villages is often difficult and requires, in many cases, days of travel.) This way of structuring the elections aimed to facilitate voters in casting their ballots on election day (ONPE 2023).

Citizens’ obligations on election day

Voting is mandatory for all eligible citizens aged between 18 and 70 years, after which voting becomes optional, as established in article 9 of the Organic Elections Law (Peru 2019). Those who do not fulfil their voting obligation are subject to fines. In the ERM of 2022, these ranged from PEN 23 to 92 soles, approximately USD 7 to 24 (Redacción EC 2022). If the fine is not paid, individuals will face various restrictions, such as the inability to register any acts related to their civil status (like marriage, divorce or widowhood); to participate in judicial or administrative processes, execute notarial acts or sign contracts, to be appointed as public officials; to enrol in social programmes; and/or to obtain a driver’s licence (JNE 2022).

However, citizens may submit a request for exemption in case they are unable to attend to vote or fulfil their duty as a polling station member (JNE 2021: article 11). Various legitimate reasons for absences from the electoral process are recognized, including natural or human-made hazards. However, for the exemption or justification to be valid, it is necessary to present a copy of the document or equivalent supporting document, signed by a competent public official ‘that credibly certifies the natural/human disaster that prevented the fulfillment of the civic duty’ (JNE 2021).

The Organic Law of Elections requires polling station staff to remain in the electoral venue from 06:00 until the conclusion of the vote counting on election day (Peru 2019: article 249). According to article 55, the composition of each polling station includes three principal members, who assume specific roles, and three alternate members, who are available to replace any principal member in the event that they are unable to fulfil their duties. Members are selected by lot from a list of 25 voters assigned to each polling station. The process is conducted by the ONPE in coordination with the Civil Registry.

Article 58 of the same legislation establishes that the role of polling station members is compulsory, and those who do not fulfil this duty are also subject to a fine. In the most recent ERM, this fine amounted to approximately PEN 200, close to USD 65. The consequences for failing to pay are the same as per breaches of compulsory voting. However, polling station members can also submit requests for justification for absence, under similar grounds established for those unable to vote.

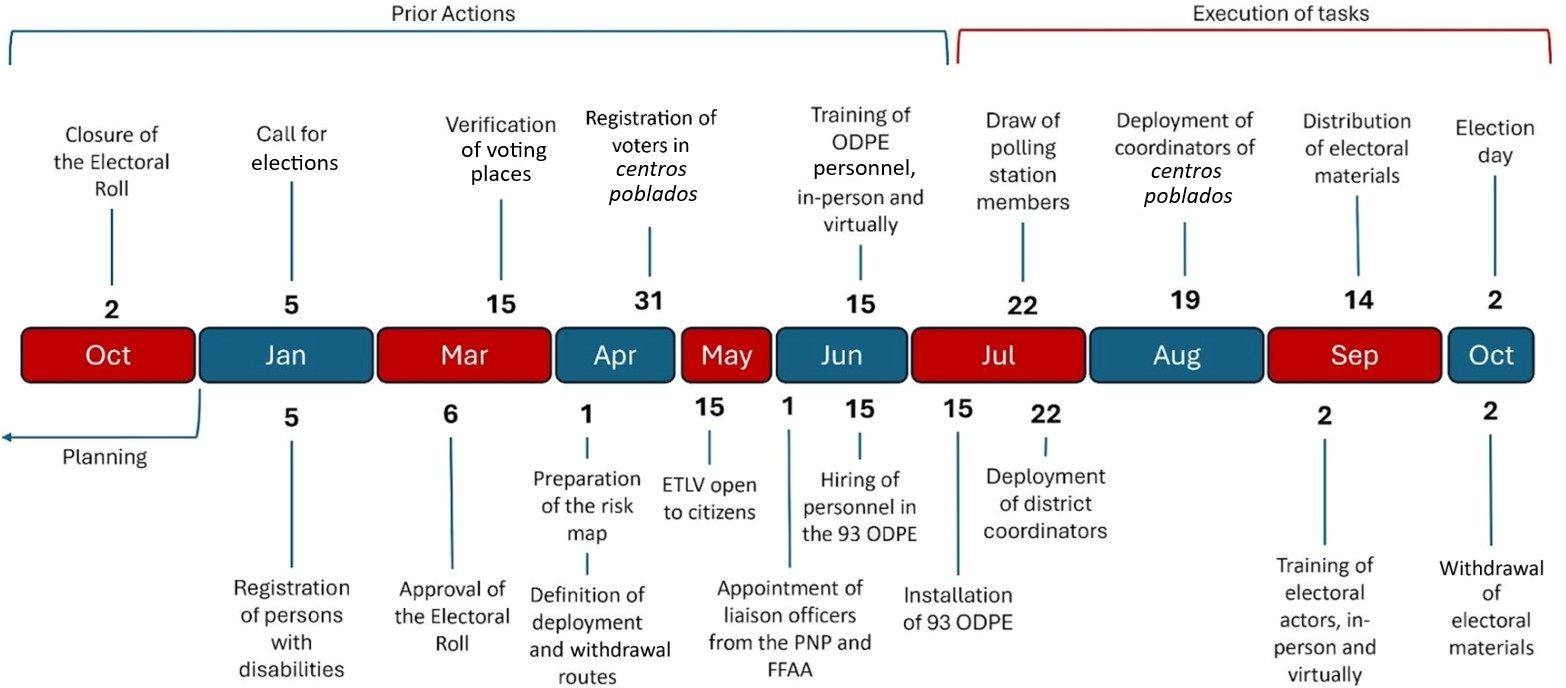

3.2. Actions taken on natural hazard risks: Pre-election

The electoral timeline approved by the JNE (2021) for the ERM 2022 begins with the closure of the electoral roll on 2 October 2021; the ONPE organizes and executes electoral activities approximately one year prior to election day. To achieve this, the ONPE carries out preliminary actions related to planning, generating guidelines, and projecting and obtaining resources, among other necessary steps. Following this, it executes the planned actions, such as training personnel and electoral actors, transporting electoral materials to the Decentralized Electoral Process Offices and polling locations, defining the composition of polling stations and selecting polling station members, among others. Some of these tasks are identified as more likely to be affected by potential natural hazards. Based on the information gathered from the interviews, the rest of this section detail the prevention and mitigation approaches taken to uphold citizens’ right to vote.

The ONPE’s General Secretariat, responsible for the security and national defence of electoral processes, prepares a risk matrix that is shared with all ONPE management units. The disaster risk matrix includes potential natural risks and how to address them, with information based on data collected by the ONPE in past elections as well as inputs from the INDECI and the CENEPRED. This information is an input for the ONPE’s sub-units to define their planning and budgeting, and to develop service level agreements whether internal or with contractors. Thus, the Deputy Office of Planning gathers the information shared by the General Secretariat and takes it into consideration when consolidating the tasks of the ONPE’s various functional units. According to the Security and National Defence specialist interviewed, the disaster risk matrix works mainly as a preventive tool, since in the event of a natural hazard, the response will come not only from the ONPE but also from the Armed Forces (FFAA), the National Police of Peru (PNP) and others (Iglesias Arévalo 2025).

Months before election day, the ONPE provides voters across the country with the opportunity to choose their preferred polling place—within their electoral district—through the platform Elige tu Local de Votación (Choose your Polling Station, ETLV). For example, for the ERM 2022 on 2 October, it was available from 15 May to 3 June. For this reason, the ONPE determines which locations will serve as polling places far in advance. This task falls to the Deputy Office of Electoral Organization and Execution, which verifies their suitability and readiness to receive voters on election day (Orna Robladillo 2025). Being mostly educational institutions, it is expected that polling station structures meet the building code established by the relevant government agency and overseen by the INDECI—and are therefore capable of operating in the event of a natural hazard. However, if sites are identified that do not meet the necessary minimum conditions, they are replaced with alternatives.

Voters’ ability to choose their polling places adds value in preventing disruptions due to natural hazards. In Peru, rainy seasons can cause landslides, blocked roads and swollen rivers; the risk of disenfranchisement due to mobility problems is reduced by having shorter distances to travel. Furthermore, the ONPE increased its polling places by 126 per cent in response to the Covid-19 pandemic (ONPE 2022a: 28) and has since maintained this change, providing voters with more options to ensure they can vote close to their homes. Similarly, the ONPE has increased polling locations in centros poblados (rural settlements) by 82 per cent (from 740 in the ERM 2018 to 1,350 in the ERM 2022) (Uipan Chávez 2022).

The tasks outlined in the ONPE’s Operational Plan are carried out by two types of personnel: permanent staff and temporary staff; the latter are contracted solely for the electoral process and include more than 60,000 individuals, whose work begins and ends according to the tasks assigned to them (Cueva Hidalgo 2025). In this regard, ONPE personnel are trained before carrying out their functions by the Deputy Office of Training and Electoral Development. Among the approximately 50 types of positions that exist during an electoral process, many are crucial—such as those related to the deployment and withdrawal of electoral materials, training polling station members,4 transmitting information from the polling places,5 transporting the electoral records to the result processing centres, assisting in district offices and operating polling places.

Above all, tasks that involve moving between districts require knowledge about how to travel and what precautions to take—whether that is transporting electoral materials or supporting remote rural districts. For this reason, the General Secretariat, in coordination with the Deputy Office of Training and Electoral Development, trains the staff in disaster risk management. The former prepares a document titled ‘Guidelines for Security and Disaster Risk Management’, which provides the ONPE’s decentralized offices with a step-by-step understanding of what they need to do at each electoral stage to prevent any impact from natural hazards or other risks (Iglesias Arévalo 2025). Additionally, both the Deputy Office of Electoral Organization and Execution and the Deputy Office of Electoral Production determine transportation routes for their personnel; these include a main route and at least one alternate route in case any difficulties arise, whether due to weather conditions, social conflict or other issues. In its contracts with transport service providers, the latter department also requires adherence to these established routes, with any changes needing the ONPE’s prior approval (Phang Sánchez 2025).

3.3. Hazard risk management: During the election

To reinforce security against natural hazards, all mobile units transporting electoral materials are accompanied by ONPE personnel, equipped with GPS trackers and provided with an escort from either the PNP or the FFAA. Both institutions are trained to respond to risk situations and are responsible for ensuring safe, timely delivery of personnel and materials.

Regarding how the PNP and FFAA coordinate with the ONPE, the General Secretariat requests a liaison officer from the Joint Command of the FFAA and from the PNP, with both officers typically being of high rank, usually a general. These officers are responsible for ensuring the deployment of escort units that accompany the electoral materials, as well as the assignment of personnel present at the polling places, and managing any emergency actions that may be required (Iglesias Arévalo 2025)—for example, the use of helicopters in the event of flooding or fires (Orna Robladillo 2025). To fulfil these functions, the ONPE’s General Secretariat prepares training materials for the FFAA and the PNP, as well as providing training both in person and online.

The ONPE’s training personnel work in urban, rural and remote districts, which means continual travel, including centros poblados. In this regard, they are in constant motion to contact polling station members, disseminate information to voters, visit district offices and transport training materials (manuals, information booklets, ballots, electoral records and support sheets for training purposes). As such, these staff have a schedule of visits, established routes and financial resources in case of incidents. Trainers are deployed days before the sessions for polling station members, to ensure that no climatic or social difficulties affect their function (Cueva Hidalgo 2025). Additionally, there is the ONPEduca platform, through which electoral actors can receive training virtually. This software tool was designed to expand the reach of training nationwide and ensure that any voter, polling station member or political organization representative who cannot attend training in person due to transportation difficulties can do so virtually (Cueva Hidalgo 2025).

During election day, 2 October 2022, no emergencies caused by natural hazards were recorded. However, it could easily have been otherwise and the heads of the ODPE, as well as the ONPE personnel present at the polling places, were equipped with the necessary tools and timely training to respond. They are required to complete the electoral operations report, which is designed to allow the actors involved in the electoral process to report on situations that hinder the proper execution of electoral operations. This report can include incidents related to natural hazards. The PNP and the FFAA at the polling places were likewise ready to respond to any requests from the ONPE, providing a continuous security presence that extended until the withdrawal of materials in the days after polling. It is worth noting that the presence of the justice ministry (Public Ministry of Peru) and the JNE at polling places also helped to ensure the proper conduct of election day.

Figure 1 shows the milestones mentioned and may help to illustrate the ONPE’s entry points for hazard risk reduction and other risk management.

3.4. Identified difficulties

Despite all the strengths outlined, there are a number of obstacles to the ONPE having a comprehensive prevention or contingency plan for disasters. One of the main barriers is related to budget availability. Effective risk and disaster management requires specific resources; however, the justification process, before the Ministry of Economy and Finance (MEF), presents a challenge. In the Peruvian context, public entities are required to justify both the use and non-use of allocated resources. This means requesting funding for activities that may not be utilized—which is integral to contingencies—proves difficult to justify (Uipan Chávez 2025). Although the MEF has a contingency fund for emergency situations, the ONPE does not have the ability to access this fund directly nor to guarantee a budget sourced from it.

Another significant challenge is the guidance received from other entities such as the INDECI and the CENEPRED. While the ONPE previously worked on a Disaster Risk Prevention and Reduction Plan, the INDECI recommended that it not be maintained and that the ONPE should instead focus solely on the Operational Continuity Plan (Iglesias Arévalo 2025). This recommendation is based on the understanding that preventing natural hazards and risks is not a function that rests with ONPE personnel, but rather with the INDECI (Iglesias Arévalo 2025), supported by the FFAA and the PNP. Since the ONPE already coordinates directly with these entities, the INDECI suggested that the aforementioned plan should not be developed.

Another difficulty noted from fieldwork (Orna Robladillo 2025) concerns polling places. In some districts, there is only one educational institution, which is prioritized as the polling location. Although, in cases where the site does not meet the appropriate conditions, the municipality or another public infrastructure could be chosen, the options in less populated districts, especially rural ones, are limited. Therefore, the infrastructure in the best condition is selected, but it is not necessarily suitable to meet the requirements for being a polling place. This limits the choice of polling locations by citizens through the ETLV platform and also represents a latent risk in the event that a significant disaster occurs during the electoral day and the location sustains considerable damage.

Finally, the Deputy Office of Electoral Production emphasized that when deploying electoral materials to areas where access may be hindered, such as in cases of rising river levels, support from the FFAA is required to utilize helicopters. Although there were no issues in 2022, the FFAA have other priority functions requiring the use of their aerial vehicles (such as delivering supplies, transporting citizens in border areas and maintaining order in conflict zones), which means they may not always have helicopters available on time to support the ONPE, or the weather may not be favourable for take-off or landing (Orna Robladillo 2025). In such cases, the risk of being unable to install polling stations in remote areas, such as centros poblados, is a persistent concern.

3.5. Improvement proposals

Despite the aforementioned difficulties, it is essential for the ONPE to continue strengthening its preventive and response capacity in the face of disasters. The following are some proposals that the ONPE plans to implement in the upcoming elections (ERM and general elections due in 2026), and others considered important to consider for future cycles. Although these proposals are not specifically designed to address disasters, they could be effectively utilized in managing natural hazards/other risks.

The first improvement is related to the development of a contingency plan for risks (Uipan Chávez 2025) that may materialize into threats or crises. While it will not focus solely on natural hazards, it will include them among the topics addressed. This contingency plan would be designed by the Planning and Budget Department, using consolidated information from all the tasks of the ONPE’s functional units. The goal is for it to serve as an operational tool at each step of the electoral process.

The second innovation is the Electoral Conflict Alert Map (MACE), a system for early warning and response (SART) designed to identify and address threats during electoral processes in a timely way. Its fundamental objective is the detection, notification and efficient dissemination of electoral incidents at the national level, allowing for an agile, precise and coordinated response among the various actors involved in electoral management and oversight (Adrianzén 2024). Additionally, it offers the option to register information through SMS messages in areas where Internet connectivity is unstable or non-existent. This feature is particularly useful in cases of natural hazards that hinder communication via Internet signals.

The MACE platform is structured into two sections. The first corresponds to the electoral conflict report, designed to report any incidents related to conflict situations during the electoral process. Although it does not include a specific category for natural hazards within the predefined categories, there is the option to incorporate these events into existing categories, such as road blockages, or destruction or loss of electoral materials (Cueva Hidalgo 2025). Second, it is possible to record incidents in the electoral day module.

Regarding the functions of National Security and Defence, two improvement options were proposed by the specialist in this area. The first is to have a multi-year National Security and Defence Plan that transcends electoral processes and is updated over time. The second proposal is to establish a new functional area for the ONPE with an allocated budget, namely a National Security and Defence Office.6 This office could continue to depend on the General Secretariat, but it would be important to establish the usual clarity of relationships through the Organization and Functions Regulation (ROF).

Regarding electoral materials distribution and collection, the ONPE’s Electoral Management Department will assume nationwide responsibility starting with the 2026 general elections and then the ERM (Phang Sánchez 2025). To this end, ‘material distribution assistants’ will be hired, who will dedicate their work specifically to accompanying the materials and ensuring that they are complete and properly documented. (Currently, those responsible for fulfilling this task are staff who perform other functions, and the accompaniment of the materials is an ancillary task.)

4. Conclusions

Peru is a country highly vulnerable to natural hazards. Earthquakes, landslides, torrential rains and other events can compromise access to polling places and the safety of electoral personnel and citizens, jeopardizing the proper conduct of the electoral process. Given this scenario, it is important to consider that in Peru, voting and serving as a polling station member are mandatory, with economic penalties for noncompliance. While this regulation aims to ensure citizen participation, its application in emergency contexts could pose additional complications for voters and EMBs.

The ONPE, as the entity responsible for electoral organization, is tasked with integrating risk management measures into its processes. This research focused on actions taken for the ERM 2022. Although the institution did not implement a specific plan on disaster management, ONPE does have strategic actions and tools to address various types of emergencies, which could include those caused by natural phenomena.

The ONPE successfully organized the ERM 2022. The 84,323 polling stations were installed, and citizens came out to vote without encountering difficulties caused by natural hazards or other issues. This was achieved because the ONPE planned its tasks months in advance, taking into consideration possible risk situations, including natural hazards, social conflict, budget execution and other factors that could affect the electoral timeline. Furthermore, it sought to facilitate the voting process for citizens, given the mandatory nature of voting, through the ETLV platform, and increased the number of polling places in centros poblados by 82 per cent, bringing voting locations closer to individuals living in more remote areas.

Although the ONPE does not have a specific plan for prevention and response to natural hazards, its Electoral Operational Plan (ONPE 2022c) includes tasks that ensure compliance with the milestones of the electoral timeline by staff and contracted services. Among the activities are the development of a disaster risk matrix shared with all management units of the ONPE; training for both permanent and temporary staff in disaster risk management; verification of the infrastructure and access of polling places; the ability to offer voters a platform to choose a polling location close to their homes; mapping of primary and alternate routes for electoral materials and ONPE personnel; coordination with the FFAA and the PNP; and the option to train polling station members, voters and representatives virtually, thereby reducing transport-related risks.

However, ONPE officials recognize that there are opportunities for improvement, both in planning and in the organizational structure of the institution itself. Thus, there are proposals to develop a contingency plan for the 2026 elections, and personnel will be hired who will primarily focus on the secure distribution and collection of election materials. Additionally, a system for early warning and response (SART) called MACE will be implemented, enabling field personnel to register incidents that occur during the election—online or via SMS. Furthermore, it is considered that having a security and defence office with an assigned budget would help enhance actions related to risk prevention, risk management tools and training on issues related to natural hazards and other sources of risk.

Abbreviations

CENEPRED Centro Nacional de Estimación, Prevención y Reducción del Riesgo de Desastes (National Centre for Estimation, Prevention, and Disaster Risk Reduction) EMB Electoral management body ERM Elecciones Regionales Municipales (regional and municipal elections) ETLV Elige tu Local de Votación (Choose your Polling Station) FFAA Fuerzas Armadas (Armed Forces) INDECI Instituto Nacional de Defensa Civil (National Institute of Civil Defence) JNE Jurado Nacional de Elecciones (National Jury of Elections) MACE Mapa de Alertas de Conflictos Electorales (Electoral Conflict Alert Map) ODPE Oficina Descentralizada de Procesos Electorales (Decentralized Electoral Processes Offices) ONPE Oficina Nacional de Procesos Electorales (National Office of Electoral Processes) PNP Policía Nacional del Perú (National Police of Peru) ROF Reglamento de Organización y Funciones (Organization and Functions Regulation) SENAMHI Servicio Nacional de Meteorología e Hidrología del Perú (National Meteorology and Hydrology Service)

References

Adrianzén, W., 'Avance del Cuaderno Electoral n.° 8. Elecciones, nulidad y conflicto en el Perú' [Preview of Electoral Notebook No. 8. Elections, nullity and conflict in Peru], Oficina Nacional de Procesos Electorales, May 2024, <https://repositorio.onpe.gob.pe/bitstream/20.500.14130/1229/1/Avance%20del%20Cuaderno%20Electoral%20N%c2%b0%208%20-%20Elecciones%2c%20nulidad%20y%20conflicto%20en%20el%20Per%c3%ba.pdf>, accessed 24 June 2025

Asplund, E., Fischer, J. and Birch, S., ‘Wildfires, hurricanes, floods and earthquakes: How elections are impacted by natural hazards’, 1 September 2022, <https://www.idea.int/news/wildfires-hurricanes-floods-and-earthquakes-how-elections-are-impacted-natural-hazards>, accessed 24 June 2025

Bündnis Entwicklung Hilft and Ruhr University Bochum (Institute for International Law of Peace and Armed Conflict, IFHV), World Risk Report 2024 (Berlin: Bündnis Entwicklung Hilft/IFHV, 2024), <https://weltrisikobericht.de/worldriskreport/>, accessed 24 June 2025

Centro Nacional de Estimación, Prevención y Reducción del Riesgo de Desastres (CENEPRED), ‘Escenario de riesgo por lluvias 2022. Pronóstico de precipitaciones en la Sierra del 30 de septiembre al 02 de octubre de 2022’ [Risk Scenario for Rains 2022. Precipitation Forecast for the Highlands from 30 September to 2 October 2022], 2022a, <https://sigrid.cenepred.gob.pe/sigridv3/storage/biblioteca//14599_escenario-de-riesgo-por-lluvias-2022-aviso-meteorologico-de-pronostico-de-precipitaciones-en-la-sierra-del-30-de-septiembre-al-02-de-octubre-de-2022.pdf>, accessed 24 June 2025

—, ‘Escenario de riesgo por lluvias 2022. Pronóstico de lluvia en la Selva del 29 de septiembre al 01 de octubre de 2022’ [Risk Scenario for Rains 2022. Rain Forecast for the Jungle from 29 September to 1 October 2022], 2022b, <https://sigrid.cenepred.gob.pe/sigridv3/storage/biblioteca//14598_escenario-de-riesgo-por-lluvias-2022-aviso-meteorologico-de-pronostico-de-lluvia-en-la-selva-del-29-de-septiembre-al-01-de-octubre-de-2022.pdf>, accessed 24 June 2025

Córdova Aguilar, H., ‘Vulnerabilidad y Gestión Del Riesgo de Desastres Frente al Cambio Climático En Piura, Perú’ [Vulnerability and Disaster Risk Management in the Face of Climate Change in Piura, Peru], Semestre Económico, 23/54 (2020), pp. 85–112, <https://doi.org/10.22395/seec.v23n54a5>

Cueva Hidalgo, C., Deputy Training and Electoral Development Manager, Electoral Organization and Regional Coordination Department, ONPE, authors’ interview, Lima, March 2025

Darnolf, S., ‘Safeguarding our elections: Enhanced electoral integrity planning’, Review of International Affairs, 38/1 (2018), pp. 39–51, <https://doi.org/10.1353/sais.2018.0004>

Defensoría del Pueblo, Supervisión defensorial: Elecciones Regionales y Municipales 2022 [Ombudsman Supervision: 2022 Regional and Municipal Elections] (Lima: Defensoría del Pueblo, 2022), <https://cdn.www.gob.pe/uploads/document/file/3873555/Reporte%20de%20Supervisión%20Electoral%20-%20ERM%202022-1%20Y.pdf.pdf?v=1669325955>, accessed 24 June 2025

Iglesias Arévalo, W., Specialist in Security and Defence, ONPE General Secretariat, authors’ interview, Lima, March 2025

Instituto Nacional de Defensa Civil (INDECI), Compendio Estadístico 2023 [Statistical Compendium 2023] (Lima: INDECI, 2023), <https://sinia.minam.gob.pe/sites/default/files/archivos/public/docs/4965310-compendio-final-af-2023-indeci.pdf>, accessed 24 June 2025

Inter American Development Bank (IADB), Indicadores de Riesgo de Desastre y de Gestión de Riesgos: Programa Para América Latina y El Caribe: Perú [Disaster Risk and Risk Management Indicators: Programme for Latin America and the Caribbean: Peru], (Washington, DC: IADB, 2015), <https://doi.org/10.18235/0009616>

Jurado Nacional de Elecciones (JNE), Resolution No 0987-2021-JNE, 3 December 2021, <https://portal.jne.gob.pe/portal_documentos/files/3827aca8-32be-4b84-ba54-a0cf61ff7ddf.pdf>, accessed 24 June 2025

—, ‘Consultar si tienes multas electorales’ [Check if you have electoral fines], 24 November 2022, <https://www.gob.pe/382-multas-electorales>, accessed 24 June 2025

Mahoney, J. and Goertz, G., ‘A tale of two cultures: Contrasting quantitative and qualitative research‘, Political Analysis, 14/3 (2006), pp. 227–49, <https://doi.org/10.1093/pan/mpj017>

Oficina Nacional de Procesos Electorales (ONPE), Memoria Institucional 2021 [Institutional Report] (Lima: ONPE, 2022a) <https://repositorio.onpe.gob.pe/handle/20.500.14130/1034>, accessed 9 September 2025

—, Resolución Jefatural [Headquarters Resolution] N.° RJ-2035-2022-JN, 24 May 2022b, <https://www.gob.pe/institucion/onpe/normas-legales/3021166-rj-2035-2022-jn>, accessed 24 June 2025

—, Resolución Jefatural [Headquarters Resolution] N° 003550-2022-JN/ONPE, 28 September 2022c, <https://cdn.www.gob.pe/uploads/document/file/3711817/RJ-3550-2022-JN.pdf.pdf>, accessed 234 June 2025

—, Informe de Evaluación Del Plan Operativo Electoral de Elecciones 2022 [Evaluation Report of the Electoral Operational Plan for the 2022 Elections] (Lima: ONPE, 2023), <https://www.onpe.gob.pe/modTransparencia/downloads/2022/EVA-POE-2022.pdf> accessed 24 June 2025

—, Resolución Jefatural [Headquarters Resolution] N.° RJ-125-2024-JN, 27 June 2024, <https://www.gob.pe/institucion/onpe/normas-legales/5703137-rj-125-2024-jn>, accessed 24 June 2025

Orna Robladillo, H., Deputy Manager of Electoral Organization and Execution, Electoral Organization and Regional Coordination Department, ONPE, authors’ interview, Lima, March 2025

Peru, Republic of, Organic Law of the National Office of Electoral Processes, Law No. 26487, 21 June 1995, <https://www.jne.gob.pe/oc/2025/Compendio-de-Legislacion-Electoral/13-Ley-Org%C3%A1nica-de-la-Oficina-Nacional-de-Procesos-Electorales-Ley-N26487.pdf>, accessed 24 June 2025

—, Organic Law of Elections, Law No. 26859, 12 December 2019, <https://www.gob.pe/institucion/congreso-de-la-republica/normas-legales/368389-26859>, accessed 24 June 2025

Phang Sánchez, J., Deputy Manager of Electoral Production, Electoral Management Department, ONPE, authors’ interview, Lima, March 2025

Redacción EC, ‘Multa Por No Votar: ¿cuánto Es y En Qué Casos Aplica?’, El Comercio, 29 September 2022, <https://elcomercio.pe/respuestas/multa-por-no-votar-cuanto-es-y-en-que-casos-aplica-elecciones-2022-tdex-revtli-noticia/>, accessed 25 May 2025

Uipan Chávez, M., Deputy Planning Manager, Planning and Budget Department, ONPE, email communication with the authors, September 2022

—, authors’ interview, Lima, March 2025

Annex A. Methodology

This study employs a qualitative analysis and adopts the ‘causes-of-effects’ approach (Mahoney and Goertz 2006). This is because it seeks to explain the outcomes in a specific case. The objective is to explore in depth the management of the risk of natural hazards during the ERM of 2022. The selection of this methodological approach responds to the need for a comprehensive analysis of the specific actions that influenced risk management in the electoral process.

For data collection, various qualitative techniques were employed. First, a detailed document review was conducted, which included the gathering and analysis of technical reports and relevant legislation primarily produced by electoral bodies. Additionally, in-depth semi-structured interviews were conducted with key actors from the National Office of Electoral Processes (ONPE).

The selection of interviewees was based on their experience and responsibility in the electoral field, as well as their connection to the ONPE’s key areas of work in the planning and development of electoral processes. In particular, we are interested in the role of five organic units. The interviews focused on gathering detailed information regarding strategic decision making, the challenges faced and the lessons learned.

The following is the list of interviewees:

Henry Orna Robladillo, Deputy Manager of Electoral Organization and Execution of the Electoral Organization and Regional Coordination Department.

According to article 106 of the ROF, this deputy office sub-management is responsible for providing assistance and monitoring the progress of operational and administrative activities in the ODPE during the electoral process, based on the Electoral Operational Plan. This is the area of the ONPE responsible for ensuring the proper development of the electoral day. To this end, it directly coordinates with the ODPE the necessary actions, monitors the budget execution of each, and determines when resource transfers should occur. Similarly, it prepares the profiles of personnel to be hired at the national level and plans the actions that need to be taken regarding organization and execution necessary for the electoral day in an integrated manner throughout the country.

To fulfil these functions, interviewee Henry Orna mentions that the deputy office sub-management is structured into three internal areas (Orna Robladillo 2025). The first is the planning and budget area, whose main responsibility is the planning of activities and general strategies, as well as the allocation of the necessary economic resources for their proper development (Orna Robladillo 2025). The second area is in charge of monitoring the activities carried out by the ODPE during the electoral process. This monitoring occurs at two levels: first, through a compliance and reporting follow-up that supervises adherence to the Electoral Operational Plan; and second, through continuous monitoring by a team tasked with coordinating daily with the ODPE to ensure that all actions are carried out as planned (Orna Robladillo 2025). Finally, there is the logistics team, which provides support for the procurement process of goods and services for the ODPE (Orna Robladillo 2025).

Carla Cueva Hidalgo, Deputy Manager of Training and Electoral Development of the Electoral Organization and Regional Coordination Department.

This unit is responsible for overseeing all activities related to electoral training, aimed at the various actors involved in the electoral processes.

In the context of the electoral process, interviewee Carla Cueva Hidalgo indicates that the deputy office sub-management assumes the responsibility of coordinating training at two levels (Cueva Hidalgo 2025). First, training is provided to the personnel contracted to perform various roles within the electoral process, such as polling station coordinators and polling place coordinators, among others (Cueva Hidalgo 2025). Second, the training is directed towards electoral actors, including polling station members, voters and armed forces, among others (Cueva 2025).

Juan Phang Sánchez, Deputy Manager of Electoral Production of the Electoral Management Department.

According to Article 72 of the ROF, this office sub-management is responsible for coordinating, executing and verifying activities related to the design, printing, storage, assembly, dispatch and distribution (deployment and withdrawal) of electoral materials, ensuring their availability for election day. It is important to specify that, for this study, when electoral materials are mentioned, it refers to ballots, voter registration records (which includes the installation records of the polling station, the polling records of voters and the vote counting records), ballot boxes, voting booths and voter lists.

Milagros Uipan Chávez, Deputy Manager of Planning of the Planning and Budget Department.

According to article 45 of the ROF, this unit is responsible for coordinating and executing the phases of the institutional planning process, including the operational activities of the Decentralized Electoral Processes Offices and the Regional Coordination Offices. This deputy office holds meetings with the different areas of the ONPE to review the planning proposed by each, ensure that the planned activities align with the electoral timeline, and consolidate them to guarantee that no tasks overlap or negatively impact the development of the electoral processes.

Walter Iglesias Arévalo, Specialist in Security and Defence of the General Secretariat.

Currently, the General Secretariat is responsible for proposing, coordinating and developing actions related to security during electoral processes, as well as carrying out the functions of national defence in accordance with the relevant regulations. To this end, it coordinates with the FFAA, the PNP, the INDECI and the CENEPRED, among other entities. Similarly, it provides guidelines and generates tools for both internal and external stakeholders of the ONPE to prevent and respond to risks or disasters within the framework of electoral processes.

About the authors

Rafael Arias Valverde is a researcher at the Institute of Social Analytics and Strategic Intelligence—Pulso PUCP. He has directed quantitative and qualitative research related to elections, citizen security and gender. He has served as deputy manager of documentation and electoral research at the National Office of Electoral Processes of Peru and coordinated its magazine, Revista Elecciones. He contributed to the case study with the conceptualization, methodological design, conducting interviews, writing its draft and the review and editing of the final document.

Wendy Adrianzén Rossi is a political scientist from the Pontificia Universidad Católica del Perú (PUCP), with expertise in both quantitative and qualitative research methods. Her academic interests include electoral issues, emerging technologies, and innovation and digital transformation in the public sector. She contributed to the project by assisting with the development of the study's structure, conducting the literature review, analyzing interviews, and drafting the document.

Contributors

Erik Asplund, Senior Advisor, Electoral Processes Programme, International IDEA.

Sarah Birch, Professor of Political Science and Director of Research (Department of Political Economy), King’s College London.

Ferran Martinez i Coma, PhD, Professor, School of Government and International Relations at Griffith University, Queensland.

© 2025 International Institute for Democracy and Electoral Assistance

International IDEA publications are independent of specific national or political interests. Views expressed in this publication do not necessarily represent the views of International IDEA, its Board or its Council members.

With the exception of any third-party images and photos, the electronic version of this publication is available under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 (CC BY-NC-SA 4.0) licence. You are free to copy, distribute and transmit the publication as well as to remix and adapt it, provided it is only for non-commercial purposes, that you appropriately attribute the publication, and that you distribute it under an identical licence. For more information visit the Creative Commons website: <http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/4.0>.

This case study is part of a project on natural hazards and elections, edited by Erik Asplund (International IDEA), Sarah Birch (King's College London) and Ferran Martinez i Coma (Griffith University).

Design and layout: International IDEADOI: <https://doi.org/10.31752/idea.2025.56>

ISBN: 978-91-7671-993-0 (PDF)

ISBN: 978-91-7671-994-7 (HTML)