Financing Electoral Management Body and Electoral Activity Costs in Sri Lanka

Executive summary

This brief examines the financing of Sri Lanka’s Election Commission (EC) and the challenges surrounding the 2023 local elections, which became an unprecedented test of the Commission’s authority and financial independence. The EC, established constitutionally in 2001 and expanded in 2020, is mandated to conduct free and fair elections, maintain the electoral register, oversee political party recognition and regulate campaign finance. However, in 2023 the government withheld funds already approved for local polls, citing the economic crisis. Despite Supreme Court rulings ordering disbursement, the Treasury and other state institutions failed to cooperate, forcing indefinite postponement. Elections were only held in May 2025 after a change in political leadership.

The episode revealed that the EC’s greatest vulnerability lies not in insufficient resources, but in its dependence on the executive for disbursement and compliance. Sri Lanka’s experience underscores that safeguarding electoral integrity requires adequate funding as well as institutional independence and protection from political interference.

Introduction

This brief examines the funding processes for the electoral management body (EMB) and elections in Sri Lanka, with a particular focus on the 2023 local elections. These elections serve as a case study of an unprecedented situation in which efforts to hold the elections were obstructed, raising critical questions about the EMB’s authority and financial autonomy. To provide context, the brief begins with a concise historical overview of the political and economic developments leading up to the elections. It then outlines the EMB’s core responsibilities and explains how its operations are typically supported through state funding. The analysis then details the significant departure from standard practice in the 2023 local elections and explores what went wrong. The brief concludes with a summary of the key findings and their implications for electoral integrity and institutional independence in Sri Lanka.

1. Historical, political and economic context

Sri Lanka is sometimes referred to as Asia’s oldest democracy, since it has embraced universal adult suffrage since 1931 (Rajapaksha 2023). In elections to the Ceylon State Council conducted in 1931 and 1936, the franchise was granted to men and women over 21 years of age (ECSL n.d.c). Following independence of the dominion of Ceylon, the 1947 Constitution provided for a bicameral legislature, comprising a popularly elected House of Representatives and a Senate that was partly nominated and partly elected indirectly by the lower House. Executive power was vested in a cabinet led by the prime minister. The governor-general, as head of state, represented the British monarch (Britannica 2025).

A new constitution was proclaimed in 1972 and Ceylon became the Republic of Sri Lanka. The 1972 Constitution created a unicameral legislature and replaced the governor-general with a president as head of state. Effective executive power, however, remained with the prime minister and cabinet (Britannica 2025). This changed in 1978, when a new constitution established a semi-presidential republic with a directly elected president who enjoys considerable powers (Miwa 2013), both formal and informal. The electoral system for presidential elections allows voters to rank up to three candidates, and these preferences are counted if no candidate wins an outright majority of votes. Thus far, this count of preferences has happened only once in electoral history, in the October 2024 presidential election (EU EOM 2024).

The 1978 Constitution changed the electoral system from first-past-the-post to the open-list system of proportional representation (PR). However, the new PR system was used first only in the 1989 parliamentary elections, due to the extension of the term of the 1977 parliament following a controversial referendum in 1982 (Jayasinghe, Reid and Welikala 2022: 18). Currently, 196 legislators are elected from district lists in 22 multi-member constituencies. The remaining 29 seats are filled from party lists based on the total number of votes polled by each party nationwide. When voters cast a ballot for the list of their preferred political party or independents, they can indicate a preference for up to three candidates on that list. The candidates with the highest numbers of preferences win the mandates allocated to the list.1 The open-list PR system is also used for provincial council elections. Local authorities—municipal, urban and divisional councils—are elected using a mixed-member proportional system (ECSL n.d.a).

Sri Lanka’s population largely identifies as Sinhalese (75 per cent) but there are also sizable minorities of Sri Lankan Tamils (11.2 per cent), Indian Tamils (4.1 per cent), and Sri Lankan Moors (9.3 per cent). Buddhists are the largest religious group (70.1 per cent), followed by Hindus (12.6 per cent), Muslims (9.7 per cent), and Christians (7.6 per cent) (Lankastatistics.com 2023). The country’s history has been marked by an armed insurgency by the Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam (LTTE), a separatist group which sought to establish an independent state in the north and east of the country. After more than two decades of bloody conflict, which claimed tens of thousands of lives, the LTTE was defeated by the Sri Lankan army in 2009 (UN 2011). Issues related to reconciliation, decentralization and the degree of autonomy accorded to provinces with substantial minority populations continue to feature in the political discourse (DeVotta 2025).

For the past three years, the country has been recovering from its worst ever economic crisis, which triggered political turmoil and brought about momentous changes in the political landscape. In March 2022, Sri Lanka’s economy collapsed, making even basic commodities unaffordable for many families. Sky-high prices hit the poor but shortages of cooking gas, key food items and petrol, as well as daily power outages, also affected the middle class (Keenan 2022). Long in the making, the crisis was precipitated by the fallout from the Covid-19 pandemic and the fiscally irresponsible economic policies of President Gotabaya Rajapaksa (Keenan 2022).

Popular anger with the entire ruling elite gave rise to a protest movement, which became known as janatha aragalaya (‘people’s struggle’ in Sinhala), or simply aragalaya. From spontaneous small-scale gatherings, the decentralized movement grew into a nationwide force increasingly determined to bring about ‘system change’, defying the government’s attempts to repress it.2 Following the beating of protesters in May 2022 by pro-government thugs, aragalaya activists attacked the homes of some 100 ruling party politicians across the country, burning many to the ground (ICG 2024). In July 2022, the protesters’ massive push to unseat President Rajapaksa was successful when he resigned and fled the country. Prime Minister Ranil Wickremesinghe became acting president and embarked on a programme of economic stabilization (ICG 2024).

Following the ousting of President Rajapaksa, the aragalaya subsided but did not disappear. After all, the wholesale change of the political system had not been achieved. President Wickremesinghe hailed from one of the two main political parties which had rotated in power since independence (Peiris 2022), and constituted part of the ruling elite that aragalaya blamed for steering Sri Lanka into the abyss. Wickremesinghe initiated a major economic reform programme (ICG 2024) but also clamped down on protests with excessive use of force, arrests and public demonization of the protesters as ‘terrorists’ and ‘fascists’ (Amnesty International 2022). He avoided any major political reform and resisted calls for accountability for the disgraced politicians (ICG 2024). It soon transpired that he was also not keen on holding elections.

2. EMB responsibilities

The Constitution currently provides for a five-member Election Commission appointed by the president of the republic on the recommendation of the Constitutional Council (article 103.1). The latter body was included in the Constitution to temper presidential appointment powers, although critics maintain that the Council’s composition is too dependent on the parliamentary majority to be conducive to that role (UN HRC 2023).3 The Election Commission of Sri Lanka (ECSL) is an expansion from the initial constitutional design, which provided for a single commissioner of elections, whose department had organized elections in Sri Lanka since independence (ECSL n.d.b). The Commission was constitutionally introduced in 2001, but a sole commissioner of elections continued to organize elections until 2015, when the first Commission was appointed. The ECSL had three members until 2020, when its membership was increased to five (ECSL n.d.d).

Commissioners, including the chair, are appointed for five-year terms. They must have distinguished themselves in any profession or in the field of administration or education. One member must be a retired official from the Department of Elections or Election Commission, above a certain rank.4 Commission members appoint a commissioner-general, who acts as the chief executive officer for the ECSL’s nearly 700 civil servants. In addition to the secretariat in the capital, the Commission has permanent offices in each of the country’s 25 administrative districts (ECSL n.d.b; Ministry of Finance 2024).

The Commission is mandated to conduct free and fair elections and referendums (Constitution article 103.2). Its related responsibilities include enumeration of voters and preparation of the electoral register; filling of vacancies in membership of parliament, provincial councils and local authorities; and recognition of political parties. The latest mandates of the ECSL, acquired in 2023 under the Regulation of Expenditure Act (REA), task it with establishing campaign spending limits for each election, receiving candidates’ reports of campaign donations and expenses, and making these reports available for public inspection (REA sections 3, 6, 7). The Commission also carries out activities to enhance electoral participation by various groups, which involves voter education as well as accommodation of voters with disabilities. These activities are often carried out in cooperation with civil society organizations (ECSL 2023).

3. The public finances management framework and the Election Commission budget

The ECSL and elections are funded from the national budget, in which the ECSL is given a separate expenditure head under ‘special spending units’, alongside the president, parliament, the office of the prime minister, judges of superior courts and other national state bodies (Ministry of Finance 2024). All government activity is predetermined and set out in plans and programmes. Annual expenditure estimates detail the government’s financial commitment for the next year’s programme of activities (ADB 2018). The Ministry of Finance is responsible for preparing the national budget and having it approved by parliament. The annual budget cycle begins in July, with a call for a submission of estimates from the spending agencies. In August, the Cabinet approves the government’s overall revenue and expenditure position and the Ministry of Finance begins discussions with the spending agencies. In October, the Cabinet approves a second memorandum on the budget, and the appropriation bill is published in the gazette and presented to the parliament for the first reading. The Appropriation Act is normally passed by parliament in December (ADB 2018).

The Election Commission annual performance report (previously, administration reports of the Commissioner of Elections) reveals how financial transparency has evolved over time.5 Reports from the 1980s provide details of activities and statistical information but make no mention of anything related to the funding of the Department of Elections. The first such mention is made in the 1993 report, which contains a new section on ‘Assets’ and discusses the cost of construction of the new secretariat building (about LKR 46 million over four years) and the acquisition of new vehicles, without specifying their cost (Commissioner of Elections 1993: section 12). Subsequent reports, however, contain little or no financial information until 2001, when the report mentions the costs incurred in connection with a referendum initiated by the president but subsequently rescinded (nearly LKR 98 million was spent on polling cards, ballots and other preparations), as well as completion of a new building for the Colombo district elections office at a cost of LKR 49 million (Commissioner of Elections 2001: sections 8 and 15).

The 2002 report breaks new ground by including a section on ‘Details of accounts’, which provides a considerable amount of financial information. This alteration does not appear to be driven by any change in the reporting requirements and is more likely to have been a result of the commissioner’s own initiative. The new section reveals, among other details, that in 2002 the Department of Elections employed 525 staff at a cost of LKR 50 million, that the total expenditure on local authority elections that year was LKR 542.6 million and that, other than elections, registration of voters constituted the major part of the department’s recurrent expenditure (Commissioner of Elections 2002: section 13). It is likely that these financial details were provided at least in part due to unmet funding needs; the report emphasizes that essential repairs to official buildings had to be delayed and the pace of computerization of electoral registers was slow (Commissioner of Elections 2002: section 13).

The same level of detail was not replicated in the 2003 report but it also included a section on details of accounts (Commissioner of Elections 2003: section 13). Subsequent reports, however, only mention funding-related issues sporadically, such as the destruction of election offices by a tsunami (Commissioner of Elections 2004: section 13) and United States Agency for International Development assistance with computerization (Commissioner of Elections 2006: section 3). However, from 2008 onwards the reports again regularly include financial information in considerable detail, albeit only in a narrative form.

Since 2019, the Election Commission’s performance reports have included comprehensive auditing and financial information in the text and numerous tables. Some of this reporting is evidently the result of new legislative requirements, as the report cites the National Audit Act, 2018. Table 1 shows the ECSL’s capital and recurrent expenditure since 2008. It reveals, perhaps unsurprisingly, that the cost of elections is rising over time, linked to inflation and increases in related service costs. Interestingly, the ECSL’s capital expenditure varies considerably, reflecting variations in infrastructure investment needs from one year to the next, as well as the ECSL’s negotiating success with the government of the day. For example, the considerable fall in capital expenditure in 2022 came in the context of an overall reduction in public spending (ECSL 2022: 58).

To assist interpretation of the data in Table 1, it should be borne in mind that if elections are held early or late in the year, some of the related expenditure would be undertaken, respectively, in the preceding or the following year. When it comes to tackling emergency situations, such as natural disasters or pandemics, related expenses will be reflected insofar as they are administered by the ECSL, but other agencies may also be involved and contribute through their budgets (DMC n.d.). Such efforts are funded from special budget allocations for emergencies (Ministry of Finance 2024).

| Year | Elections held | Recurrent expenditure, LKR million | Capital expenditure, LKR million |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2008 | 3 provincial councils 1 Local authority | 728 | 24.5 |

| 2009 | 5 provincial councils 2 local authorities | 1,513 | 25 |

| 2010 | Presidential Parliamentary | 3,995 | 44.3 |

| 2011 | Local authorities | 2,161 | 54.4 |

| 2012 | 3 provincial councils | 912 | 23.8 |

| 2013 | 3 provincial councils | 1,315 | 40.6 |

| 2014 | 3 provincial councils | 2,095 | 79.1 |

| 2015 | Presidential Parliamentary | 5,803 | 46.1 |

| 2016 | — | 578 | 55.3 |

| 2017 | — | 789 | 105.8 |

| 2018 | Local authorities | 4,053 | 52.6 |

| 2019 | Presidential 1 local authority | 3,989 | 124.3 |

| 2020 | Parliamentary | 7,301 | 71.2 |

| 2021 | — | 788 | 82 |

| 2022 | — | 852 | 23.2 |

| 2023 | Local authorities (postponed) | 1,632 | 45.9 |

| 2024* | Presidential Parliamentary | 11,050* | 143* |

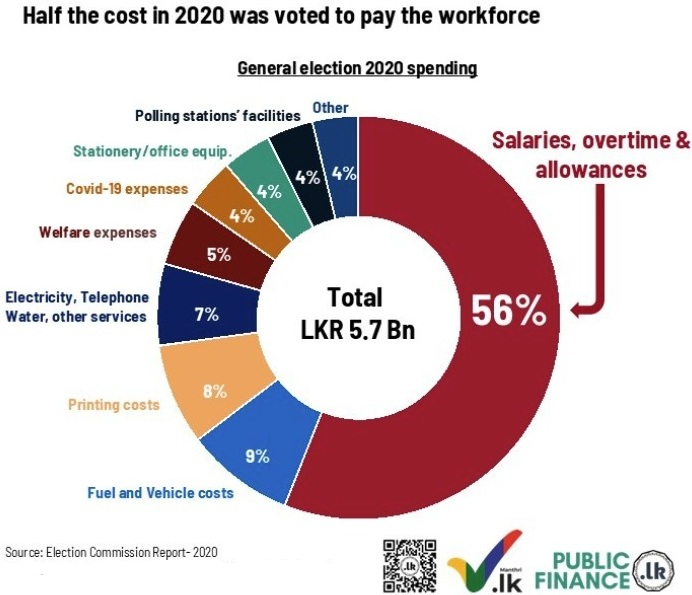

Figure 1 illustrates how an election budget is spent, using the example of the 2020 parliamentary elections. It shows that human resources constitute the bulk of election costs, with salaries, overtime and allowances to election personnel accounting for more than half the election budget. In addition to the ECSL’s permanent staff, this includes polling station and counting centre officials who are recruited from among civil servants but paid by the ECSL. Vehicles, printing, electricity and communications are also major expenses. Importantly, the annual revision of the voter register is not reflected in Figure 1 but is included in the total recurrent expenditure for 2020 in Table 1.

4. How the 2023 local elections floundered

The primary source of information on the holding of local authority elections in 2023 is the Supreme Court of Sri Lanka, which delivered its judgment on the resulting applications in August 2024 (Supreme Court 2024). This judgment resolved four separate petitions lodged by politicians and civil society activists, which were consolidated into one proceeding as their subject matter was the same—the failure to hold local elections. The context described below frequently draws on the facts established by the Supreme Court.

Local authority elections had been held in February 2018 in all but one locality in Sri Lanka (Elpitiya, where due to their prior annulment, the elections were held in October 2019). Accordingly, the four-year terms of elected local authorities expired in March 2022. As permitted by law, in January 2022 the Minister of Public Administration, Provincial Councils and Local Government extended the terms of local authorities that were due to expire by one year, until March 2023. Around EUR 10 billion had been allocated to the Election Commission in the 2023 budget estimates (Supreme Court 2024: 29).

In order to hold the elections within six months of the expiration of the elected members’ terms of office, as required by the legislation, the ECSL issued a call for nominations in December 2022 and appointed returning officers and assistant returning officers to conduct the elections. On 4 January 2023, the ECSL announced that nominations for candidates for the local authority elections would be accepted between 18 and 21 January, and that electoral deposits would be accepted until noon on 20 January (Supreme Court 2024: 28–30). The ECSL also proceeded with arrangements for postal voting.

Indications of government interference with the elections began to emerge in the public domain in early January. According to newspaper reports, President Wickremesinghe summoned the ECSL to a meeting (Economynext 2023a; Supreme Court 2024: 31) where the President is said to have made clear his view, voiced also by other members of the ruling party, that the time was not right for local elections, due to the country’s economic crisis (Economynext 2023b).

On 10 January, the Secretary to the Ministry of Public Administration issued a circular addressed to all the district secretaries who had been appointed to serve as returning officers for the 2023 local elections. In this circular, the Secretary stated that the Cabinet of Ministers had directed him to notify the district secretaries not to accept deposits from candidates for the local authority elections until further notice. The ECSL swiftly reacted with its own circular, issued on the same day, reiterating that receiving deposits and nominations was the duty of all returning officers. The ECSL also summoned the Secretary to question him about the circular. The Secretary promptly withdrew the circular and apologized to the Election Commission, according to an EC press release (Supreme Court 2024: 30).

On 11 January, the ECSL told the press that it was united in wanting to see the elections delivered (Economynext 2023a). Responding to media reports that some of its members had resigned, the ECSL issued a press release on 26 January rejecting such assertions as false (Supreme Court 2024: 31). On 30 January the ECSL had to deny another claim, made by the Director General of Government Information, that the ECSL had not sent a required notice to the government printer. The ECSL emphasized that it had taken all the necessary steps according to the law for the conduct of the elections (Supreme Court 2024: 32).

On 2 February, the Secretary to the Ministry of Finance issued a budget circular addressed to all government ministries and departments, informing them of a Cabinet decision taken on 30 January to only release funds relating to maintaining essential services. On 6 February, President Wickremesinghe, in his capacity as the Minister of Finance, Economic Stabilization and National Policies, submitted for the government’s approval a Cabinet Memorandum on ‘Maintaining Essential Public Services in the Most Difficult Financial Circumstances’. This document proposed to order the Treasury to provide resources only for the essential public expenditure listed in the Memorandum until the condition of government revenues had improved. Local authority elections were not listed among the 22 items in this Memorandum. The Cabinet approved the Memorandum on 7 February (Supreme Court 2024: 32–33).

The Election Commission found its efforts to organize the 2023 local elections stonewalled by the government and the agencies whose cooperation is indispensable. The government printer did not provide the postal voting cards on the due dates, forcing the ECSL to announce the postponement of postal voting on 14 February. The printer further claimed that it could not complete the printing of postal ballot papers because sufficient security was not being provided by the police. In the meantime, the Secretary to the Ministry of Finance communicated to the ECSL that any further release of funds for the conduct of local elections would need the approval of the Minister of Finance, that is, President Wickremesinghe (Supreme Court 2024: 34–35).

On 24 February, the ECSL announced the postponement of the local elections scheduled for 9 March, with a new date to be announced later, and asked the speaker of parliament to intervene in order to obtain finances from the Treasury. On 3 March 2023 the Supreme Court granted interim orders ‘restraining and/or preventing the Minister of Finance and the Secretary of the said Ministry from withholding the funds allocated by the Budget for the year 2023 for the purpose of conducting Local Government Elections’ (Supreme Court 2024: 35–36).

These Supreme Court orders, however, did not have the desired effect. The ECSL Chair sent a letter to the Secretary of the Ministry of Finance on 7 March, stating that that the Commission had decided to advise returning officers to fix the date of 25 April 2023 for conducing the local polls and requesting the release of funds to the police, the government printer and postal departments. The Secretary of the Ministry of Finance replied that, as per the Cabinet decision, the ECSL’s request would be referred to the Minister of Finance for his approval and steps would be taken to release the funds once approval had been granted. Such approval never materialized (Supreme Court 2024: 35–36). On 11 April the ECSL postponed the 2023 elections again, this time indefinitely (Adaderana.lk 2023).

In August 2024, the Supreme Court’s judgment ordered the Election Commission ‘to schedule the Local Government Elections 2023 at the earliest possible with due regard to their duty to hold other elections as required by law’. Local elections were eventually conducted on 6 May 2025, after parliament adopted a special act cancelling the electoral steps undertaken in 2023. They were preceded by the presidential election in September 2024, in which the incumbent President Wickremesinghe was soundly defeated, and snap parliamentary polls in November 2024 that handed President Anura Kumara Dissanayake’s National People’s Power a supermajority in parliament (DeVotta 2025).

5. Challenges, risks and solutions

The failure to conduct local elections in 2023 prompted questions about the financial independence of the Election Commission. The withholding of funds allocated in the budget for elections by the executive was unprecedented. What could be done to overcome such a scenario in the future? As a part of public administration, the ECSL relies on the good faith of the legislature and the executive to fulfil its mandate. A funding mechanism that secures the ECSL’s budget in isolation from these branches of government is hardly feasible and might also be undesirable from an accountability perspective. Judging from the Commission’s own reports prior to and after the 2023 local elections controversy, elections in Sri Lanka have been funded adequately. In informal conversations with the author, long-term officers of the ECSL and civil society commentators could not recall any other occasion when the ECSL had been starved of funds.

The Supreme Court rejected the government’s justification for the withholding of funds for the 2023 local polls, linked to the economic crisis. The Court pointed out that the Treasury had been involved in 2023 budget preparation and should have exercised vigilance if spending the funds allocated would have caused immense hardship to the economy (Supreme Court 2024: 49). While acknowledging that the country was experiencing an economic crisis, the Court nonetheless found that the Cabinet’s selection of funding priorities to exclude elections, just a few weeks after the budget and passage of the Appropriation Act, was potentially ‘arbitrary and for some other purpose’ (Supreme Court 2024: 57). Commenting on the government’s argument that the Cabinet’s spending priorities were directed at protecting people’s dignity by addressing essential needs, the Court poignantly remarked that:

Slave, or a vassal or a serf in a feudal system, might have had his basic essential needs fulfilled, in contrast the dignity of people in a democratic society, with its pros and cons, highly rests on their ability to partake in governance whether it is central, provincial or local, through voting in an election.

(Supreme Court 2024: 58)

The failure of the 2023 local elections highlights issues with the rule of law and with the ability of the ECSL to enforce its powers, rather than with the financing of elections. The Supreme Court’s judgment reveals a clear display of non-compliance with the Election Commission’s lawful requests. The Court found that that President Wickremesinghe’s actions amounted to an infringement of the fundamental rights guaranteed under the Constitution ‘due to arbitrary and unlawful conduct … which resulted in the non-holding of the Local Government Elections 2023’ (Supreme Court 2024: 73). The President appeared to be bent on preventing the local elections from going ahead despite political protests (Francis 2023) and civil society appeals (ANFREL 2023). His insistence that the public purse could not afford elections was widely seen as an attempt to avoid a trouncing of the ruling elite at the polls (Uyangoda 2023), something he was able to delay but ultimately not to avert as the 2024 presidential and parliamentary elections demonstrated (DeVotta 2025). The local elections eventually held in May 2025 did not face any financial or organizational obstacles and citizen observers praised the ECSL for its efforts to ensure fairness and integrity (PAFFREL 2025).

Mitigation of the risks to the future funding of elections thus turns to the questions of whether any additional safeguards should be introduced into the process and what these might be. Importantly for this discussion, the Supreme Court also laid the blame for the failed elections with the ECSL. The Court pointed out that ‘other than requests made, I cannot find any directions given by the Election Commission either to any department or [to] the Secretary of the Treasury’. This led it to conclude that ‘the Commission failed in issuing necessary directions to the relevant authorities when necessary’ (Supreme Court 2024: 53). The Court’s analysis does not mention that the ECSL came under considerable pressure over its decision to press ahead with the local elections. Several members of the ECSL received death threats (CMEV 2023) directed at them and their families, and some members had requested, and were provided with, police protection. One commissioner resigned (Dissanayake 2023; Factseeker.lk 2023). This may well be part of an explanation as to why the Commission did not ‘exercise its strength and powers fully to make the election process a success’ (Supreme Court 2024: 54).

Two areas could therefore be identified to strengthen the ECSL in situations where it is not given the required cooperation by other authorities of the state. First, the appointment process of the commissioners could be reviewed to include more safeguards of their independence, for example, by allowing nominations from associations and bodies known for their independent stance. Second, the powers of the ECSL to enforce compliance with its directives could be enhanced. In this regard, the experiences of countries in Central and Latin America that have endowed their EMBs with judicial powers, such as Costa Rica and Uruguay, deserve careful examination.

6. Conclusions

Sri Lanka’s EMB has a track record of holding competitive and well-organized elections going back several decades. These elections have been adequately funded and the EMB has followed the same budget process as other public institutions. The annual revision of voter registers, recognition of political parties and voter education are just some of the activities undertaken by the Election Commission in addition to organizing polls.

The ECSL’s annual budget is divided into recurring costs, which fund elections and other activities, and capital costs, which cover maintenance of the Commission’s infrastructure throughout the country. Human resource costs constitute more than half of all election expenses. Annual reports reveal that election costs have risen in the past decade.

The withholding of funds allocated in the 2023 budget for local elections prompted discussion of whether the Commission’s financial independence should be better secured. While there is scope to explore additional safeguards in the budget disbursement process, the ECSL’s ability to fully exercise its powers could also be strengthened through the appointment of independently minded commissioners and by endowing the Commission with greater legal authority to enforce compliance with its directives.

References

Adaderana.lk, ‘Local govt election postponed for second time’, 11 April 2023, <http://www.adaderana.lk/news.php?nid=89713>, accessed 12 February 2025

Amnesty International, ‘Sri Lanka: Authorities’ crackdown on protest rights must end’, 8 September 2022, <https://www.amnesty.org/en/latest/news/2022/09/sri-lanka-authorities-crackdown-on-protest-rights-must-end/>, accessed 12 February 2025

Asian Development Bank (ADB), Public Financial Management Systems—Sri Lanka: Key Elements from a Financial Management Perspective (Manila, Philippines: ADB, 2018), <https://www.adb.org/publications/public-financial-management-systems-sri-lanka>, accessed 12 February 2025

Asian Network for Free and Fair Elections (ANFREL), ‘Sri Lanka CSOs seek support of diplomatic missions to call for local government elections’, 7 April 2023, <https://anfrel.org/sri-lanka-csos-seek-support-of-diplomatic-missions-to-call-for-local-government-elections/>, accessed 12 February 2025

Britannica, ‘The Republic of Sri Lanka’, Updated August 2025, <https://www.britannica.com/place/Sri-Lanka/The-Republic-of-Sri-Lanka>, accessed 22 August 2025

Centre for Monitoring Election Violence (CMEV), ‘Statement on death threats received to two members of the Election Commission’, 19 January 2023, <https://cmev.org/2023/01/19/statement-on-death-threats-received-to-two-members-of-the-election-commission/>, accessed 12 February 2025

Commissioner of Elections, Administration Report for the year 1993, <https://elections.gov.lk/en/download/admin_reports_E.html>, accessed 12 February 2025

—, Administration Report for the year 2001, <https://elections.gov.lk/en/download/admin_reports_E.html>, accessed 12 February 2025

—, Administration Report for the year 2002, <https://elections.gov.lk/en/download/admin_reports_E.html>, accessed 12 February 2025

—, Administration Report for the year 2003, <https://elections.gov.lk/en/download/admin_reports_E.html>, accessed 12 February 2025

—, Administration Report for the year 2004, <https://elections.gov.lk/en/download/admin_reports_E.html>, accessed 12 February 2025

—, Administration Report for the year 2006, <https://elections.gov.lk/en/download/admin_reports_E.html>, accessed 12 February 2025

DeVotta, N., ‘Sri Lanka’s peaceful revolution’, Journal of Democracy, 36/1 (January 2025), pp. 79–92, <https://doi.org/10.1353/jod.2025.a947885>

Disaster Management Centre (DMC), ‘Right to Vote Amidst Disasters: Guidelines and Operational Plan’, [n.d.], <https://www.dmc.gov.lk/images/pdfs/2024%20GENERAL%20ELECTION%20EMERGENCIES%20-%20Operational%20Guidelines%20-%20FINAL%20-%208.11.24%20newww%20%206666%20(1)_compressed-compressed.pdf>, accessed 12 February 2025

Dissanayake M., ‘EC member PSM Charles resigns’, Ceylon Today, 26 January 2023, <https://ceylontoday.lk/2023/01/26/ec-member-p-s-m-charles-resigns/>, accessed 12 February 2025

Economynext, ‘Sri Lanka Election Commission undivided on local govt polls: Commission chair’, 11 January 2023a, <https://economynext.com/sri-lanka-election-commission-undivided-on-local-govt-polls-commission-chair-108958/>, accessed 12 February 2025

—, ‘Sri Lanka local govt polls: President’s party adamant time is not right for elections’, 23 January 2023b, <https://economynext.com/sri-lanka-local-govt-polls-presidents-party-adamant-time-is-not-right-for-elections-109961/>, accessed 12 February 2025

Election Commission of Sri Lanka (ECSL), ‘Local Authorities Election System’, [n.d.a], <https://elections.gov.lk/en/elections/elections_local_authorities_election_system_E.html>, accessed 12 February 2025

—, ‘Organogram’, [n.d.b], <https://elections.gov.lk/en/aboutus/aboutus_ORGANOGRAM_E.html>, accessed 12 February 2025

—, ‘Our history’, [n.d.c], <https://elections.gov.lk/en/aboutus/aboutus_history_E.html>, accessed 12 February 2025

—, ‘Election Commission’, [n.d.d], <https://elections.gov.lk/en/aboutus/aboutus_election_commission_E.html>, accessed 12 February 2025

—, Performance Report for the year 2022, <https://elections.gov.lk/en/download/admin_reports_E.html>, accessed 12 February 2025

—, Performance Report for the year 2023, <https://elections.gov.lk/en/download/admin_reports_E.html>, accessed 12 February 2025

European Union Election Observation Mission (EU EOM), ‘Sri Lanka 2024, Presidential Elections’, 21 September 2024, Final Report, <https://www.eods.eu/library/EU%20EOM%20LKA%202024%20FR%20(1).pdf>, accessed 12 February 2025

Factseeker.lk, ‘When did PSM Charles resign?’, 16 October 2023, <https://factseeker.lk/blog/news/when-did-psm-charles-resign/>, accessed 12 February 2025

Fernando, B., ‘Sri Lanka: The changing meanings of system change’, Asian Human Rights Commission, 10 May 2022, <http://www.humanrights.asia/news/ahrc-news/AHRC-ART-012-2022/>, accessed 12 February 2025

Francis, K., ‘Sri Lanka police fire tear gas at election protest: 15 hurt’, AP, 26 February 2023, <https://apnews.com/article/politics-sri-lanka-colombo-cb7ad21a28ad9fac237144cb9e90ca4d>, accessed 12 February 2025

International Crisis Group (ICG), ‘Sri Lanka’s bailout blues: Elections in the aftermath of economic collapse’, Report No. 341m, 17 September 2024, <https://www.crisisgroup.org/asia/south-asia/sri-lanka/341-sri-lankas-bailout-blues-elections-aftermath-economic-collapse>, accessed 12 February 2025

Jayasinghe, P., Reid, P. and Welikala, A., ‘Parliament: Law, history and practice’, Centre for Policy Alternatives, 17 January 2022, <https://www.cpalanka.org/parliament-law-history-and-practice/>, accessed 12 February 2025

Keenan, A., ‘Sri Lanka’s economic meltdown triggers popular uprising and political turmoil’, International Crisis Group, 18 April 2022, <https://www.crisisgroup.org/asia/south-asia/sri-lanka/sri-lankas-economic-meltdown-triggers-popular-uprising-and-political-turmoil>, accessed 12 February 2025

Lankastatistics.com, ‘Composition of population of Sri Lanka’, 2023, <https://lankastatistics.com/economic/composition-of-population.html>, accessed 12 February 2025

Ministry of Finance, Planning and Economic Development of Sri Lanka, Approved Budget Estimates 2024, <https://www.treasury.gov.lk/web/2024-approved-detailed-budget-estimates>, accessed 12 February 2025

Miwa, H., ‘Strong president and vulnerable political system in Sri Lanka’, in Kasuya Y. (ed.), Presidents, Assemblies and Policy-making in Asia (Palgrave Macmillan, 2013), <https://doi.org/10.1057/9781137315083_7>

Peiris, P., Catch-All Parties and Party-Voter Nexus in Sri Lanka (Palgrave Macmillan: Singapore, 2022), <https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-16-4153-4>

People’s Action for Free and Fair Elections (PAFFREL), Election Day Communique, Local Authorities Election, 6 May 2025, <https://paffrel.com/images/2025/PDFS/EDC.pdf>, accessed 12 February 2025

Rajapaksha, N., ‘The cost of politics in Sri Lanka’, Westminster Foundation for Democracy, November 2023, <https://costofpolitics.net/wp-content/uploads/2024/08/Sri-Lanka-cost-of-politics-WFD.pdf>, accessed 12 February 2025

Supreme Court of the Democratic Socialist Republic of Sri Lanka, Applications 69/2023, 79/2023, 90/2023, 139/2023, Judgement 22 August 2024, <https://supremecourt.lk/?melsta_doc_download=1&doc_id=b9510cff-692d-4f7c-8983-654ff3c6fe40&filename=sc_fr_69_23.pdf>, accessed 12 February 2025

United Nations, Report of the Secretary-General’s Panel of Experts on Accountability in Sri Lanka, 31 March 2011, <https://reliefweb.int/sites/reliefweb.int/files/resources/POE_Report_Full.pdf>, accessed 12 February 2025

United Nations, Human Rights Committee (HRC), ‘CCPR/C/LKA/CO/6: Concluding observations on the sixth periodic report of Sri Lanka’, 26 April 2023, <https://www.ohchr.org/en/documents/concluding-observations/ccprclkaco6-concluding-observations-sixth-periodic-report-sri>, accessed 12 February 2025

Uyangoda, J., ‘Sri Lanka’s local elections are a major threat to the ruling class’, Himal South Asian, 13 February 2023, <https://www.himalmag.com/comment/srilanka-local-elections-aragalaya-tax-policy-economic-crisis-ranil-wickremesinghe-rajapaksas>, accessed 12 February 2025

Abbreviations

ECSL Election Commission of Sri Lanka EMB Electoral management body LTTE Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam PR Proportional representation REA Regulation of Expenditure Act, 2023

Acknowledgements

The author would like to express his gratitude to the Election Commission of Sri Lanka, to Gayanthi Ranatunga; Leena Rikkilä-Tamang, Director of International IDEA’s Asia-Pacific Programme, for their insightful comments on the draft; Therese Pearce Laanela, Head of Electoral Processes of International IDEA; and to Oliver Joseph from International IDEA’s Electoral Processes Programme for his guidance in developing this brief, as well as Lisa Hagman and Tahseen Zayouna from International IDEA’s Publications team for providing advice on the design and layout and managing the publication process.

About the Author

Vasil Vashchanka holds a Master of Laws degree from Central European University (Budapest) and is currently an external researcher at the Research Centre for State and Law of Radboud University (Nijmegen), focusing on political rights and political finance. Vasil worked on the rule of law and democratization at the Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe’s Office for Democratic Institutions and Human Rights in Warsaw between 2002 and 2012. He was an officer with International IDEA’s Electoral Processes team (Stockholm) between 2012 and 2014. Vasil regularly serves as a consultant for international organizations on legal and electoral issues. He has participated in numerous international election observation missions, authored expert reviews of legislation and published academically.

© 2025 International Institute for Democracy and Electoral Assistance

International IDEA publications are independent of specific national or political interests. Views expressed in this publication do not necessarily represent the views of International IDEA, its Board or its Council members.

With the exception of any third-party images and photos, the electronic version of this publication is available under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 (CC BY-NC-SA 4.0) licence. You are free to copy, distribute and transmit the publication as well as to remix and adapt it, provided it is only for non-commercial purposes, that you appropriately attribute the publication, and that you distribute it under an identical licence. For more information visit the Creative Commons website: <http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/4.0>.

Design and layout: International IDEA

DOI: <https://doi.org/10.31752/idea.2025.55>

ISBN: 978-91-7671-996-1 (PDF)

ISBN: 978-91-7671-997-8 (HTML)