Financing Electoral Management Body and Electoral Activity Costs in Czechia

Executive summary

Czechia is a multiparty parliamentary democracy, with a prime minister as head of the government and a president as head of state. The president, the parliament, and local and municipal councils are directly elected by the people. The electoral management body (EMB) follows a governmental model, with the permanent state-level Election Commission presided over by the minister of the interior. The elections are funded from the state budget and the work of the EMB is considered a civil service function. The part of the state budget entitled General Treasury Management provides the resources for organizing elections, which is done in a decentralized manner.

This brief analyses the costs of electoral administration and activities in Czechia. It assesses the legal and regulatory framework for electoral funding, concluding that the legislation and operational arrangements are adequate for ensuring that sufficient funds are allocated to elections and for protecting the stability and neutrality of the EMB. Using data from a short survey distributed to randomly selected municipalities, this brief also investigates the practical implementation of this framework, identifying small challenges and highlighting possible improvements in the future.

1. Historical, political and economic context

Czechia is a multiparty parliamentary democracy with a prime minister as head of the government and a president as head of state. The parliament comprises two chambers: the 200-member Chamber of Deputies (lower chamber) and the 81-member Senate (upper chamber). Members of the Chamber of Deputies are elected for a four-year term using a proportional representation system, with a 5 per cent threshold. The electoral constituencies for the Chamber of Deputies’ elections correspond to the national administrative regions (Kraje). There are 14 constituencies (Czech Republic 1995). The members of the Senate are elected for a six-year term in a two-round system in single-member constituencies, with one-third of all senators elected every two years. In cases where the mandate of any senator ends—for example, as a result of death or resignation—supplementary elections are called in the relevant constituency within 90 days. The year before a senatorial election is due is, however, an exception, and no supplementary elections take place (Czech Republic 1995). Since 2013, the president has also been elected directly, in a two-round system, although the powers of the office remain the same (according to amendments to the Czech Constitution in 2013; see Czech Republic 1992). The Czechs elect the president for a five-year term.

Some characteristics of the Czech parliamentary system are weak parliamentarianism and unstable governments. Since the dissolution of Czechoslovakia in 1993, there have been 16 governments, of which 3 were administrative (non-elected). The fall of a government, however, does not necessarily trigger new elections, and hence does not contribute to increased electoral costs. It may, however, cause lower government efficiency. In addition, taking a long time to form a government (e.g. 2018), frequent votes of no-confidence and weak coalitions all have a negative impact on voters’ trust in the democratic system (Cabada 2017; Freedom House 2019). These long-term challenges and the introduction of the direct election of the president triggered a discussion about the potential move to semi-presidentialism in Czechia (Hloušek 2014).

The Czech Government is decentralized, with 14 self-governing administrative units at regional level, and 6,254 municipalities. The capital Prague has a special status, being considered both a region and a municipality, although it is represented by a single set of elected representatives. Every four years (not concurrently), elections take place for the regional councils (45 to 65 representatives each) and municipal councils (5 to 55 representatives each). Prague may have up to 70 representatives. The most recent municipal elections took place in 2022, while regional elections were held in 2024 (Czech Statistical Office 2024). Under Czechia’s open-list proportional representation electoral system, the law provides for the replacement of a representative that has been terminated outside the regular electoral period, without the need to conduct new elections. This provision only applies, however, if the council’s decision-making capacity remains within the law. The minister of the interior must call new elections in those municipalities or regions where the number of elected representatives falls below the minimum required by law during an electoral term or where the elected municipal council collapses due to political ‘no-confidence’ in the executive (Czech Republic 2001, 2000). Supplementary municipal elections are frequent in Czechia, indicating some government instability at the local level. The legislation, which is generally very comprehensive, provides, in this specific case, a space for politicking, including group resignations from elected positions in a municipal council to effect a change in the distribution of power. Resignation is the main reason for the termination of a mandate and leads to a proliferation of local elections and hence increased electoral costs. Between 2014 and 2018, for example, there were 144 supplementary municipal elections (Senate 2024). In 2023 and 2024 respectively, the minister of the interior called 30 and 21 new municipal elections (Ministry of the Interior 2025). Several senators submitted a draft law in 2024 to amend the Law on Elections to Municipal Councils (Czech Republic 2001), in an attempt to address this specific issue. The draft law proposes that only those representatives whose mandates have been terminated should need new elections rather than the entire municipal council. If adopted, this draft law could also remove the motivation for group resignations (Senate 2024).

Since the establishment of local self-government in 2000, the regions and municipalities have also faced challenges with the efficient use of resources (Železník and Rosičková 2013). In August 2024, the State Administration Journal (Kameníčková 2024) reported that the under-utilization of the budgets allocated to municipalities and regions has increased annually.

Czechia is a member of the European Union. The election to the European Parliament takes place every five years. Starting in 2025, Czech citizens will finally be able to cast a postal vote from abroad in European, presidential and parliamentary elections (Czech Republic 1995: para. 57a; Czech Republic 2024).

Overall, Czechia is considered a high-income country (World Bank 2024). Over the past 25 years, it has experienced several structural changes and challenges. The first significant development came with the entry of Czechia into the EU, which boosted its economic growth. The global economic crisis in 2008, the stagnation of the industrial sector in 2016, and the Covid-19 pandemic from 2020 onwards, however, slowed overall growth and were followed by additional ‘shocks’, such as the energy crises and the Russian invasion of Ukraine.

2. Electoral management body responsibilities

Czechia is a member of the Council of Europe and the United Nations, and has ratified major international and regional instruments pertaining to democratic elections (International Justice Resource Center 2020). The legal framework for elections in Czechia primarily comprises the 1992 Constitution (last amended in 2013; Czech Republic 1992), the 1993 Charter of Fundamental Rights and Freedoms (amended in 1998; Czech Republic 1993), and laws governing each election, including the Law on election of the President (Czech Republic 2012), Law on Elections to the Parliament, Law on Elections to the European Parliament (Czech Republic 2003), Law on Elections to Regional Councils, and Law on Elections to Municipal Councils (as amended) (Czech Republic 1995, 2000, 2001). The Ministry of the Interior issues supplementary regulations and directives to complement the legal framework (Ministry of the Interior 2025).

The EMB in Czechia follows a governmental model (International IDEA n.d.). The elections are administered in a decentralized manner by multiple bodies at the national, regional and local levels. The electoral bodies include the national Election Commission, Ministry of the Interior, Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Czech Statistical Office, regional and municipal offices, and mayors. There are nearly 15,000 local-level electoral commissions. Consular and diplomatic offices abroad are responsible for out-of-country voting, where applicable, according to the Law on Election Administration (Czech Republic 2024).

The Election Commission is a permanent body, presided over by the minister of the interior, and comprises 10 members from different ministries and state agencies. Members and deputies, except the president, are nominated by the government. The Election Commission is responsible for the organization and technical preparation of all elections and referendums, including the publication of the results (Law on Election Administration; Czech Republic 2024). The Ministry of the Interior is responsible for certain aspects of the technical preparation of elections, including the procurement of ballot papers. The Ministry of Foreign Affairs is responsible for holding elections abroad. The Czech Statistical Office ensures the processing of the election results before passing them to the Electoral Commission, while regional offices and municipalities organize elections in their respective areas. Regional offices are also responsible for candidate registration in their respective constituencies, and municipalities are charged with voter education (Law on Election Administration; Czech Republic 2024).

There are no significant challenges surrounding the electoral administration in Czechia. The Election Commission does not have political party representation as it is under the authority of the minister of the interior. Transparency and accountability are sought through political party ‘oversight’ within the membership of the local-level electoral commissions. Each political party that has registered a candidate list can nominate, at the latest 36 days before the election, one representative and one deputy to the local-level electoral commission. The members can be delegated to each local-level electoral commission within the electoral constituency where it submitted the candidacy (Law on Elections to the Parliament; Czech Republic 1995).

3. The public financial management framework

Elections are funded from the state budget. The law divides the state budget into sections entitled ‘chapters’, according to certain thematic areas and the competencies of specific state administration offices. The Chamber of Deputies of the Parliament adopts the main budget chapters, upon the proposal from the government, as a special law. The thematic areas that are more general in nature and do not belong under the specific responsibility of any particular state office, as well as areas where the budget cannot be fully determined at the time the state budget is being approved, are part of Chapter 398—Všeobecná pokladní správa (General Treasury Management). The Ministry of Finance directly administers the General Treasury Management chapter, which also includes electoral funding (Ministry of Finance 2024).

The state budget is approved in four phases. During Phase I (January to September every year), the Ministry of Finance analyses the economic prognosis for the upcoming year and compiles the budget for each chapter, with contributions from the responsible state administration office. The Ministry of the Interior submits the prognosis for elections. The prognosis for elections is prepared in three-year cycles (medium-term cycle of the state budget) and confirmed annually. The Ministry of Finance subsequently presents the draft state budget to the government, which submits the draft state budget to the Chamber of Deputies no later than the end of September. In Phase II, which takes place between October and December, the Chamber of Deputies discuss the draft law on the state budget in three readings. Upon approval, the president signs the law on the state budget (Czech Fiscal Council n.d.; Šrámková and Verešová 2024).

Phase III focuses on the realization and quarterly evaluation of the state budget (January to December of the budget year). In Phase IV (January to September the following year), the Ministry of Finance and responsible state administration offices submit the final accounts for government approval and publication on the Ministry of Finance website. The Chamber of Deputies and the Supreme Audit Office issue an opinion on the general government finances. The Czech Fiscal Council issues an annual Report on Compliance with the Rules of Budgetary Responsibility (Czech Fiscal Council n.d.). As such, electoral expenses follow the same rules of accountability and financial diligence as other public processes.

4. Funding for elections

How are the elections funded? The work of the EMB is a civil service function fully funded by the state budget. The General Treasury Management chapter of the state budget provides the resources necessary for organizing elections, which the Ministry of Finance gives to the municipalities in the form of a grant. These grants are distributed in a decentralized manner through the regional state administration offices. The size of a grant is determined by the Ministry of the Interior, based on the expenditure from previous elections. The current size of the grant per electoral voting district is calculated at CZK 32,000 (approx. EUR 1,270) for one-round elections, and CZK 48,000 (approx. EUR 1,900) for two-round elections. The size of a voting district should ideally be about 1,000 voters, but in more remote areas it can be smaller—to ensure access to the polling station—although must be a minimum of 10 voters. The size of a voting district is not, however, considered when allocating the grant (Šrámková and Verešová 2024).

The compensation of the local-level electoral commission members presents the main challenge for the accurate allocation of the budget. Each local-level electoral commission must have at least four members where there are up to 400 registered voters, and five members for over 400 voters (Law on Election Administration; Czech Republic 2024). Each political party running in the constituency can nominate one member and one deputy to each local-level electoral commission. For the presidential election, every party represented in parliament can also nominate a member and substitute to each local-level electoral commission. The Ministry of the Interior submits the updated budget to the Ministry of Finance four months before elections, without knowing the final numbers of local-level electoral commission members. The number of local-level electoral commission members can be 4 or over 30, depending on the number of political candidates running. The size of a grant is, therefore, determined by the Ministry of the Interior based on an ideal scenario, not considering either the size of the voting districts or the number of actual local-level electoral commission members.

There is, however, some flexibility in the implementation of the grants within the regulatory framework. The municipalities with more than one voting district can use the grant flexibly within different voting districts (such as spending more on some voting districts than others). The expenditure must, however, remain within the rules set out in the 2013 Ministry of Finance Directive on the procedure for municipalities and regions in financing elections (hereafter the ‘Ministry of Finance Directive’; Ministry of Finance 2013). The Ministry of Finance Directive describes, in detail, what expenditure is allowed and provides specific limits for spending on certain items. To avoid the municipality exceeding its allocated budget while remaining within the Ministry of Finance Directive, each municipality pre-funds its expenditure from its own budget and is compensated after the elections by the regional state administration office or directly by the Ministry of Finance. The municipality submits the expenditure report first to the regional office. The regional office may reallocate resources saved by some municipalities to those with higher expenditures immediately after the election. Otherwise, the Ministry of Finance compensates additional expenses directly to the municipalities no later than May of the following year (Šrámková and Verešová 2024).

5. Implementation of the election funding

How is the electoral funding spent in practice? To assess the framework for election funding in Czechia, it is necessary to review the practical implementation of the Ministry of Finance Directive. For that reason, 270 municipalities were randomly selected from around the country, and contacted with a survey, which 48 municipalities then completed. The sample surveyed comprised: 21 municipalities with 1 electoral voting district (44 per cent); 13 municipalities with 2 to 5 voting districts (27 per cent); 5 municipalities with 5 to 10 voting districts (10 per cent); 3 municipalities with 11 to 20 voting districts (6 per cent); and 6 municipalities with more than 20 voting districts (13 per cent). The survey questions asked about the most recent elections to the European Parliament (2024) and the overall implementation of the Ministry of Finance Directive. While the survey is not a full statistical sample, it provides good insight into the implementation of electoral funding in Czechia (for the full survey questions, see Annex A).

In terms of the resources given to the municipalities to organize the elections, most municipalities that responded to the survey ended their post-election accounts either with zero (13 per cent) or with a positive balance that they returned to the Ministry of Finance after the elections (75 per cent). However, 12 per cent of municipalities surveyed ended with a negative balance and had to be reimbursed post-election. All the municipalities that spent more money on the elections than they were allocated had fewer than 10 voting districts, while the municipalities with the highest positive balance after the elections were those with a higher number of voting districts. This most likely reflects the possibility of using the budget flexibly within the municipality. The larger the municipality, the more easily it can compensate for the differences between smaller and larger electoral voting districts. Most municipalities that responded to the survey (81 per cent) thought the amount provided for elections was sufficient. One of the reasons given by the municipalities that considered the budget insufficient was that it was difficult to purchase adequate electoral materials due to the limitation specified in the Ministry of Finance Directive. This restricted municipalities from spending all the resources they needed.

The Ministry of Finance Directive regulates in detail the materials that municipalities can purchase from the election grant. It often states the maximum price for procurement of specific goods (see Table 1).

| Item | Limitation (if any) | Maximum price (if regulated); amount includes VAT |

|---|---|---|

| Basic office items, calculators and USB sticks | Calculators and USB sticks can only be bought once every five years; maximum one per voting district | Maximum price for USB sticks and calculators up to CZK 200 (approx. EUR 8) |

| Postal fees | — | — |

| Installation and running of the ICT equipment (rent of the ICT equipment is possible if the municipality does not have its own) | Purchase of the ICT equipment is not allowed | The regular price (not specified) |

| Travel expenses for the local-level electoral commission members | Travel must be approved by the mayor or a municipality head; transport from residence to the meetings/offices of the local-level electoral commissions is not covered | — |

| Rent of offices necessary for local-level electoral commission work, including for the training of local-level electoral commission members (if municipality cannot offer own space); the audiovisual equipment can also be rented | — | The regular price (not specified) |

| Polling booths (or other equipment to ensure secrecy of the vote) | Can be purchased only once every five years | Maximum price per booth up to CZK 1,000 (approx. EUR 40) |

| Distribution of ballot papers to the voters and compensation for compiling envelopes with the ballots | — | Maximum CZK 8.18 (approx. EUR 0.32) + CZK 1 (approx. EUR 0.04) per voter without taxes |

| Refreshment for the local-level electoral commission members | Except for alcoholic beverages | CZK 118 per person (approx. EUR 4.7) |

| Special compensation for the local-level electoral commission members | — | — |

| Communication line for each polling station | Procurement of phones and sim cards cannot be covered | — |

| Hand sanitizers, face masks, gloves and other protective equipment | Only if the use of protective equipment is established by the special health regulations | — |

According to the municipalities surveyed, the Ministry of Finance Directive prices are more or less realistic; however, 48 per cent of respondents stated that one or two items are undercosted and cannot be purchased for the price indicated. The main issue was with the price of purchasing polling booths, which reportedly could not be secured for the price in the directive. The municipalities surveyed also raised the food allowance and compensation for the local-level electoral commission members, which they believed should be higher.

The local-level electoral commission members receive the following compensation:

President: CZK 2,200 (approx. EUR 87)

Registrar: CZK 2,100 (approx. EUR 83)

Member: CZK 1,800 (approx. EUR 71)

In cases where multiple elections take place simultaneously, the compensation increases by CZK 400 (approx. EUR 16). Where there is a runoff, the electoral commission president and registrar receive an additional CZK 1,000 (approx. EUR 40) and the members CZK 700 (approx. EUR 28) each. Members of local-level electoral commissions who are employed are entitled to time or salary compensation (Ministry of the Interior 2025). The argument for increasing the compensation is that it would improve people’s motivation to serve in the local-level electoral commissions. However, in contrast, working for the local-level electoral commission is often considered a civic duty and a contribution to democracy (Šrámková and Verešová 2024).

The municipalities should receive their election budget 20 days before the elections; however, some indicated that they have only received it two weeks or even a day before the elections. While, so far, the municipalities have had sufficient resources to pre-finance elections, ideally, such late payments should not take place. Furthermore, as there is generally no issue with the availability of a budget for the elections, the pre-financing should be limited. The municipalities that exceed the budget can receive their compensation as late as the following year after elections in May. This delayed compensation happens in cases where the regional state offices do not sort the accounts and refer them directly to the Ministry of Finance (Šrámková and Verešová 2024).

The local-level electoral commissions that responded to the survey indicated that they have positive cooperation with the other state institutions involved in elections (Ministry of Finance, Ministry of the Interior, regional state administration offices) and were happy with the information they received in relation to electoral funding. The survey seems to confirm that there is an adequate legal and regulatory framework for electoral financing in Czechia, with only minor recommendations for improvements needed.

6. Electoral costs

How much do elections in Czechia cost? To assess electoral costs, the study analysed the data provided by the Ministry of Finance (Krupka 2025) and established the trend for the last 10 years. Furthermore, using the example of the 2023 presidential election, this brief provides an overview of the breakdown of electoral costs by recipient entity (relevant state institution) involved in the electoral preparation and by the main items of expenditure.

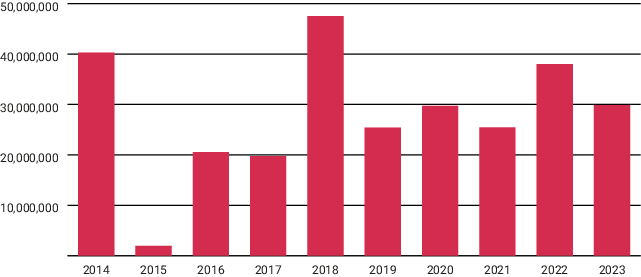

During the last 10 years, the Czechs voted in an average of 1.7 elections per year, excluding supplementary elections for local administrations. The average cost per year amounted to some EUR 27,852,279. With approximately 8.3 million registered voters, this amounts to EUR 3.34 per registered voter per year. The number is indicative and consists solely of the costs allocated to specific elections, not the regular state administration functions involved in electoral organization. Compared with reported figures for electoral costs globally—ranging from as low as USD 3 per voter to over USD 200 (Neufeld 2017)—the figure for Czechia could be considered reasonable. The data on electoral costs in the Euro-American space is not generally available, and the various countries would be difficult to compare due to different systems of addressing and accounting for electoral costs, varied contexts and a lack of a unified methodology to establish electoral costs. For that reason, the section below merely provides an overview of the electoral costs in Czechia and demonstrates the latest trends.

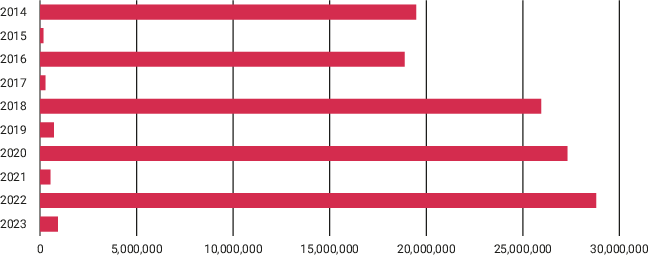

Figure 1 shows annual electoral costs over the past 10 years. The highest costs were registered in 2014, 2018 and 2022—years when municipal elections took place, which is most likely because of the correlation between the higher number of candidates and electoral costs. The municipal elections are also more complicated when it comes to establishing electoral results. The years 2014 and 2018 also each had three regular elections in a single year (see Table 2, which shows the types of elections held between 2014 and 2023).

| Presidential | Deputies | Senate | Regions | Municipality | European Parliament | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2023 | X | |||||

| 2022 | X | X | ||||

| 2021 | X | |||||

| 2020 | X | X | ||||

| 2019 | X | X | ||||

| 2018 | X | X | X | |||

| 2017 | X | X | ||||

| 2016 | X | X | ||||

| 2015 | ||||||

| 2014 | X | X | X |

Overall, the final budget allocated for an election through the budgetary process is always higher than the actual expenditure. This indicates that there are sufficient available resources for the EMB to conduct elections, and sufficient resources to compensate municipalities, in cases where there has been over-expenditure, in May of the following year. The availability of resources is important for the EMB to fulfil its legal functions efficiently (OSCE/ODIHR 2023a: 40).

| Final budget allocated (EUR) | Expenditure (EUR) | Budget utilization (percentage) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2023 | 32,640,134 | 29,863,246 | 91.49 |

| 2022 | 44,780,090 | 38,019,456 | 84.90 |

| 2021 | 29,654,279 | 25,479,161 | 85.92 |

| 2020 | 32,609,081 | 29,705,068 | 91.09 |

| 2019 | 27,951,378 | 25,407,950 | 90.90 |

| 2018 | 50,260,294 | 47,518,242 | 94.54 |

| 2017 | 27,848,283 | 19,736,181 | 70.87 |

| 2016 | 23,817,391 | 20,545,180 | 86.26 |

| 2014 | 47,730,066 | 40,285,980 | 84.40 |

While the total electoral expenses do not show a clear annual increase due to various combinations of elections held every year, the cost of elections is undoubtedly getting higher. For a better idea of the trends in electoral costs, it is necessary to compare individual elections in Czechia. This study compares the last three presidential elections, as well as the costs of the parliamentary and local elections over the last 10 years.

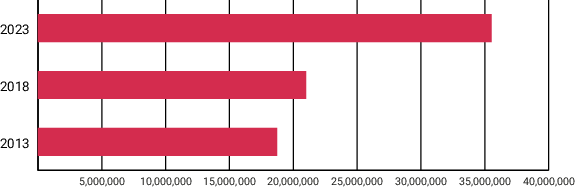

For the presidential election, the costs increased by 90 per cent between 2013 and 2023 (see Figure 2, which shows costs for the 2013, 2018 and 2023 presidential elections).

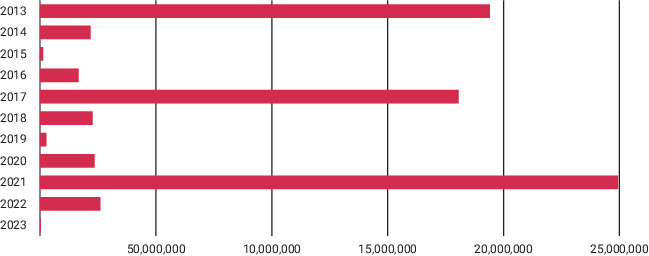

The elections for the Chamber of Deputies took place in 2013, 2017 and 2021, while the elections for one-third of the Senate took place in 2014, 2016, 2018, 2020 and 2022. An approximate comparison between the Chamber of Deputies and the Senate can therefore only be made between the Chamber of Deputies elections for 2013 and 2021—which show a 28 per cent increase—and the Senate elections for 2014 and 2022—which show a 19 per cent increase (separate supplementary Senate elections are not considered).

Lastly, the municipal elections (2014, 2018 and 2022) and elections of regional representatives (2016 and 2018) show a 48 per cent increase between 2014 and 2022. The costs, however, also include supplementary polls, so the calculation is approximate.

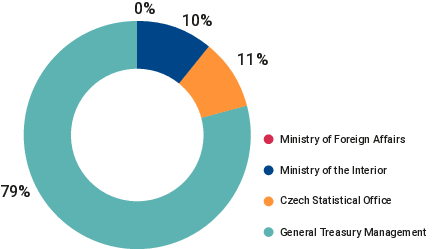

The budget for elections is distributed among the key institutions according to their legal responsibilities in the electoral process (see 2: Electoral management body responsibilities). To analyse the cost breakdown per institution, this study looked at the 2023 presidential election, including out-of-country voting. The election budget may cover any overtime undertaken by public servants involved in elections. The General Treasury Management chapter of the state budget represents the budget distributed to the regional offices and municipalities for conducting elections in their areas, and forms the biggest part of the electoral budget (79 per cent), followed by: the budget for the activities of the Ministry of the Interior, including ballot printing (11 per cent); the budget for the Czech Statistical Office, responsible for processing electoral results (10 per cent); and the budget for the Ministry of Foreign Affairs for organizing elections abroad (0.3 per cent).

| Ministry of Foreign Affairs | 80,603 |

| Czech Statistical Office | 2,853,648 |

| Ministry of the Interior | 3,417,301 |

| General Treasury Management | 23,511,694 |

| Total | 29,863,246 |

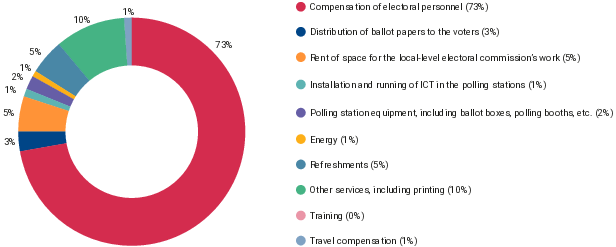

Lastly, this brief looked at the breakdown of the main electoral costs per item, again analysing the 2023 presidential election. The analysis shows that the key expenditure for the election included:

- compensation for the local-level electoral commission members and overall costs of electoral personnel;

- various services, including printing of ballot papers, financial and legal services, and maintenance costs;

- rent of space for the local-level electoral commission’s work;

- refreshments for the election workers;

- distribution of ballot papers to the voters—postal services;

- polling station equipment, including ballot boxes, polling booths etc.; and

- installation and running of the information and communication technology (ICT) in the polling stations.

7. Conclusions

This study analysed the costs of electoral administration and activities in Czechia, focusing on expenditure by the EMB. The costs of election administration in Czechia can be considered reasonable, on the lower side of the global range for electoral costs. At the same time, the electoral administration in Czechia is perceived as professional and impartial (OSCE/ODIHR 2023b). The inclusion of elections as a function of the state administration undoubtedly decreases the costs of the electoral process. The budgetary process and resource allocation allow for the financial autonomy of election administration, which plays an important role in safeguarding its independence and capacity to fulfil its function efficiently. The EMB and responsible institutions are allocated sufficient funds (the budget allotted is always higher than actual expenditure). This is achieved by the election budget being consolidated within the national budget. Procedures are also in place for election administration to be given additional funding through the General Treasury Management, in case of unforeseen circumstances. In certain cases, however, the municipalities have to pre-finance elections. While pre-financing has been available and has not, so far, jeopardized the conduct of elections, its use should be limited to ensure that municipalities have adequate resources for their other functions. Consideration should be given to options for the immediate compensation of municipalities incurring additional electoral expenses.

The legislation for and the practicalities of implementation of the electoral process provide an adequate framework to ensure the allocation of sufficient funds for elections, which also allows for stable funding—something that is vital to protect electoral management from undue political influence. In line with the UN Convention against Corruption (UNODC 2004), electoral funding is bound by the same rules of accountability and controls as other items in the national budget, ensuring the effective use of resources according to law. Electoral funding is also transparent.

The current Ministry of Finance Directive is valid until 31 December 2025 and will be replaced by a new legal regulation (Šrámková and Verešová 2024). This provides an opportunity to address minor challenges, such as insufficient budgets to procure specific items included in the Ministry of Finance Directive. Comprehensive market research and a survey of the municipalities would contribute to informed analysis and adequate funding. The compensation for the local-level electoral commission members could also be reviewed, taking into account the practical experience of the municipalities.

The years 2025 and 2026 will bring several changes that will likely increase the electoral budget in Czechia. The digitalization of state administration means that citizens are allowed to prove their identity with an electronic identity card

Abbreviations

e-ID Electronic identity card EMB Electoral management body ICT Information and communication technology

Acknowledgements

The author would like to express her gratitude to the Czech Ministry of the Interior, Election Department, and the Czech Ministry of Finance, Public Relations Unit, for providing timely and comprehensive information. It provided great insights into electoral funding in Czechia. The author would also like to thank Oliver Joseph from International IDEA’s Electoral Processes Programme for his guidance in developing this brief, and Lisa Hagman from International IDEA’s Publications team for providing advice on the design and layout as well as managing the publication process.

Cabada, L., ‘Nestabilita českých vlád po roce 2000 – příčiny a důsledky’ [Instability of Czech governments after 2000 – reasons and consequences], in L. Tungul (ed.), Pravicová řešení politických výzev pro rok 2018 [Right-wing solutions to political challenges for the year 2018] (Prague: TOPAZ, 2017)

Czech Fiscal Council, Vše o veřejných financích [Everything about public finances], [n.d.], <https://www.rozpoctovarada.cz/o-verejnych-financich/vse-o-verejnych-financich>, accessed 29 November 2024

Czech Republic, Constitution of the Czech Republic (1992, last amended 2013)

—, Charter of Fundamental Rights and Freedoms (1993; last amended 1998), <https://www.usoud.cz/fileadmin/user_upload/ustavni_soud_www/Pravni_uprava/AJ/Listina_English_version.pdf>, accessed 3 March 2025

—, Law No. 247/1995 Sb. on Elections to the Parliament of the Czech Republic (1995, as amended)

—, Law No. 130/2000 Sb. on Elections to Regional Councils (2000, as amended)

—, Law No. 491/2001 Sb. on Elections to Municipal Councils (2001, as amended)

—, Law No. 62/2003 Sb. on Elections to the European Parliament (2003)

—, Law No. 71/2012 Sb. on Direct Elections of the President (2012, as amended)

—, Law No. 88/2024 Sb. on Election Administration (2024)

Czech Statistical Office, Výsledky voleb a referend [Results of elections and referendums] (2024), <https://www.volby.cz/index.htm>, accessed 9 December 2024

Freedom House, Freedom in the World 2019, Czechia (2019), <https://freedomhouse.org/country/czech-republic/freedom-world/2019>, accessed 5 December 2024

Hloušek, V., ‘Is the Czech Republic on its way to semi-presidentialism?’, Baltic Journal of Law & Politics, 7/2 (2014), pp. 95–118, <https://doi.org/10.1515/bjlp-2015-0004>

International IDEA, Electoral Management Design Database, [n.d.], <https://www.idea.int/data-tools/data/electoral-management-design-database>, accessed 24 January 2025

International Justice Resource Center, Czech Republic Factsheet, January 2020, <https://ijrcenter.org/country-factsheets/country-factsheets-europe/czech-republic-human-rights-factsheet/>, accessed 6 December 2024

Kameníčková, V., ‘Dospěje někdy územní samospráva k vyrovnanému rozpočtu?’ [Will the public administration ever achieve a balanced budget account?], Deník veřejné správy [Public Administration Journal], 19 August 2024, <https://www.dvs.cz/clanek.asp?id=6985520>, accessed 8 December 2024

Krupka, L., Ministry of Finance, email communication with the author, 6 January 2025

Ministry of Finance, Směrnice Ministerstva financí o postupu obcí a krajů při financování voleb [Directive on the procedure of municipalities and regions in financing elections (Ministry of Finance Directive)], 2013 (last amended 2023)

—, ‘Závěrečný účet kapitoly 398 – Všeobecná pokladní správa za rok 2023’ [Final account for the Chapter 398 – General Treasury Management 2023], 2024, <https://www.mfcr.cz/cs/rozpoctova-politika/statni-rozpocet/plneni-statniho-rozpoctu/2023/zaverecny-ucet-kapitoly-398-vseobecna-pokladni-spr-55982>, accessed 7 December 2024

Ministry of the Interior, Volby [Elections], 2025, <https://mv.gov.cz/volby>, accessed 29 November 2024

Neufeld, H., ‘Election costs: Informing the narrative’, International IDEA, 21 December 2017, <https://www.idea.int/news/election-costs-informing-narrative>, accessed 13 January 2025

Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe (OSCE) Office for Democratic Institutions and Human Rights (ODIHR), Handbook for the Observation of Election Administration (Warsaw: OSCE/ODIHR, 2023a), <https://www.osce.org/files/f/documents/0/4/544240.pdf>, accessed 30 November 2024

—, ‘The Czech Republic Presidential Election 13–14 and 27–28 January 2023, ODIHR Election Expert Team Final Report’, 9 June 2023b, <https://www.osce.org/files/f/documents/2/0/545815.pdf>, accessed 13 January 2025

Senate, ‘Návrh senátního návrhu zákona senátorů Jiřího Oberfalzera, Petra Štěpánka a dalších senátorů, kterým se mění zákon č. 491/2001 Sb., o volbách do zastupitelstev obcí a o změně některých zákonů, ve znění pozdějších předpisů’ [Senate Draft Law presented by Senators Jiri Oberfalzer, Petr Stepanek and others, that amends Law. No. 491/2001 Sb., on elections to municipal councils and amendments of some other laws], 2024, <https://www.senat.cz/xqw/webdav/pssenat/original/112810/94623>, accessed 13 January 2025

Šrámková, Z. and Verešová, A., author’s interview, 10 December 2024

United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC), United Nations Convention against Corruption, 2004, <https://www.unodc.org/documents/brussels/UN_Convention_Against_Corruption.pdf>, accessed 3 March 2025

World Bank, World Bank Country and Lending Groups, 2024, <https://datahelpdesk.worldbank.org/knowledgebase/articles/906519-world-bank-country-and-lending-groups>, accessed 28 November 2024

Železník, O. and Rosičková, J., ‘Přehled základních nedostatků fungování státní správy’ [Overview of the main challenges in the functioning of state administration], Deník veřejné správy [Public Administration Journal], 25 June 2013, <https://www.dvs.cz/clanek.asp?id=6601376>, accessed 8 December 2024

The survey focused on the practical implementation of the Ministry of Finance Directive and the overall assessment of the practicalities of electoral funding in Czechia. The survey was distributed randomly to 270 municipalities, with 48 completing a response.

| No. of voting districts | No. of respondents (municipalities) | |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | 21 |  |

| 2–5 | 13 | |

| 6–10 | 5 | |

| 11–20 | 3 | |

| >20 | 6 | |

| Total | 48 |

This question compared the budget received for the 2024 election to the European Parliament with the money actually spent. The table below shows the number of municipalities that ended with even (zero) or positive final accounts, as well as the municipalities that ended with a negative account and had to be reimbursed.

| Budget received vs used | No. of municipalities | |

|---|---|---|

| Final account = 0 | 6 |  |

| Final account positive (money returned to the Ministry of Finance) | 36 | |

| Final account negative (Ministry of Finance had to reimburse the municipality after election) | 6 |

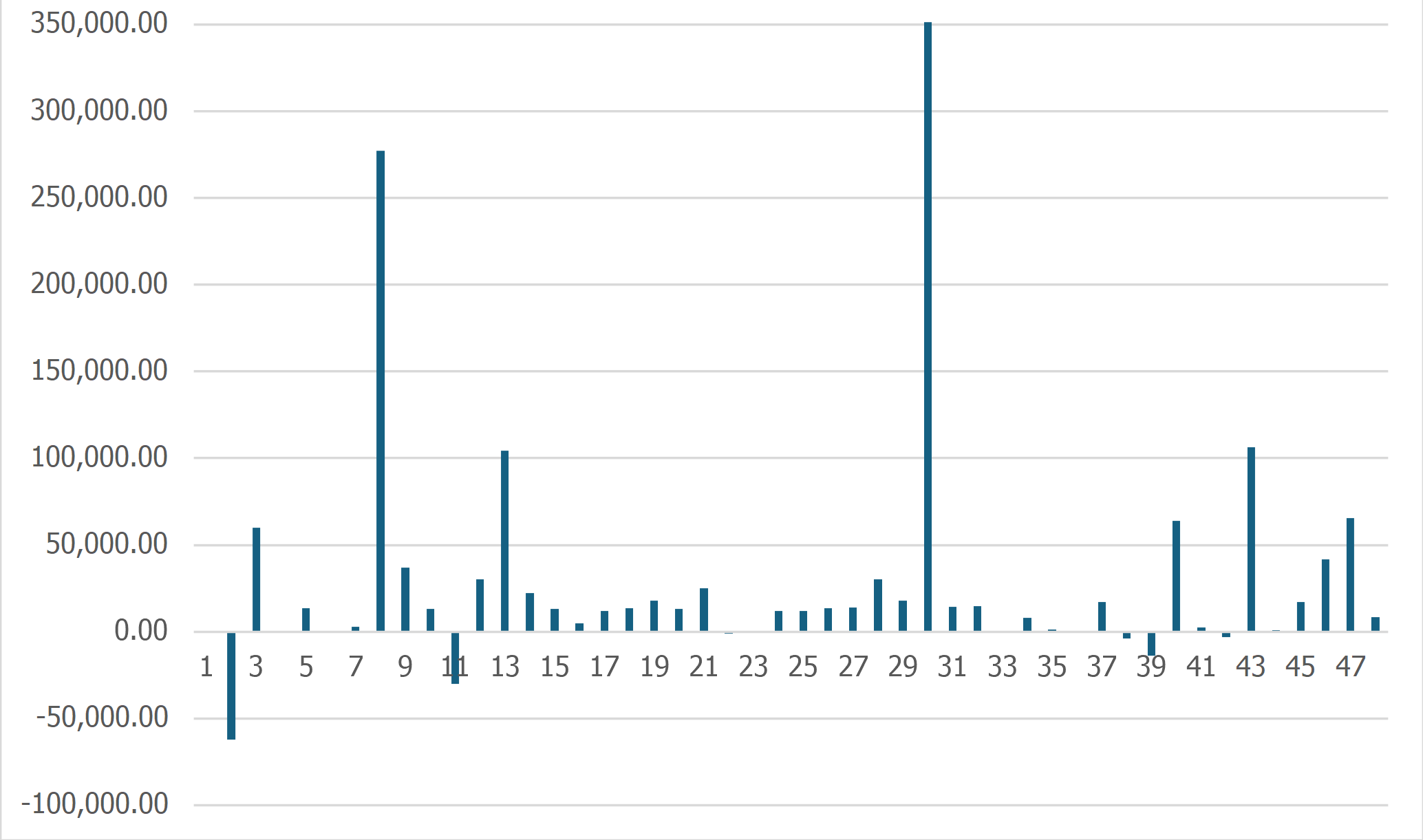

Balance between budget received and returned

Note: The figure shows the balance between the budget received and returned for municipalities who responded to the survey.

The analysis also shows the correlation between the highest number of voting districts in the municipalities and the highest positive balance after the election.

| 10 voting districts | CZK 106,200 |

| 18 voting districts | CZK 104,315 |

| 30 voting districts | CZK 60,000 |

| 40 voting districts | CZK 277,174 |

| 57 voting districts | CZK 351,360 |

| Answer | No. of respondents | |

|---|---|---|

| Yes | 39 |  |

| No | 9 |

| Answer | No. of respondents | |

|---|---|---|

| Yes | 42 |  |

| No | 6 |

Summary of comments to Question 4

As stated by respondents to the survey, money for elections was received from as little as within one day before the election to as much as two to three months before the election. One municipality indicated that materials needed to be secured before elections, so a faster reimbursement of additional costs would be welcome.

| Answer | No. of respondents | |

|---|---|---|

| Realistic and sufficient | 19 |  |

| More or less realistic but 1 or 2 expenses are underfunded | 23 | |

| Not realistic—more than 2 items cannot be bought within the limits of the directive | 6 |

Summary of responses to Question 6

The main issues raised are listed here. An increase in compensation for the local-level electoral commission members was suggested, including an increase in the allowance for refreshments. The directive should include funding for more items needed for elections and/or increase the limits set for procurement of some electoral equipment (especially the polling booths, for which the costs as stipulated in the directive were not seen as realistic). Some municipalities suggested that it would be better to put limits on overall expenses only, and not individual items. In addition, the frequency with which it was possible to procure certain items (e.g. calculators, USB sticks every five years) was mentioned as not realistic and difficult in terms of accounting, since invoices are only stored for three years.

| Answer | No. of respondents | |

|---|---|---|

| Very positive | 14 |  |

| Generally positive | 32 | |

| Generally negative | 1 | |

| Negative | 1 |

| Answer | No. of respondents | |

|---|---|---|

| Clear and sufficient | 26 |  |

| Clear and sufficient in most cases | 20 | |

| Not always clear/sufficient | 1 | |

| Unclear/insufficient | 1 |

Additional comments for questions 7 and 8 (summary)

The communication and collaboration with other state institutions on electoral funding was generally assessed positively, as reactive and flexible. Some municipalities particularly appreciated the work of the regional state offices. While most municipalities saw the information provided to them as clear and accurate, several indicated that it was complex and could be more timely.

Overall, the municipalities did not provide much additional assessment of the electoral funding in Czechia, stating that they were generally content with the system. The compensation for local-level electoral commission members, and more flexible regulation of eligible expenses, were both mentioned again in the majority of comments.

About the author

Lenka Homolková is an election and governance specialist with over 15 years of experience in electoral assistance and observation. She has worked with and/or been a consultant for various institutions, including the UN, EU, OSCE/ODIHR, International Foundation for Electoral Systems, International IDEA, and the Czech Government, in more than 20 countries in Africa, Europe and Asia. She holds a PhD from Masaryk University in Brno, Czechia, and a master’s degree from the European Inter-University Center for Human Rights and Democratization.

© 2025 International Institute for Democracy and Electoral Assistance

International IDEA publications are independent of specific national or political interests. Views expressed in this publication do not necessarily represent the views of International IDEA, its Board or its Council members.

With the exception of any third-party images and photos, the electronic version of this publication is available under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 (CC BY-NC-SA 4.0) licence. You are free to copy, distribute and transmit the publication as well as to remix and adapt it, provided it is only for non-commercial purposes, that you appropriately attribute the publication, and that you distribute it under an identical licence. For more information visit the Creative Commons website: <http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/4.0>.

Design and layout: International IDEA

DOI: <https://doi.org/10.31752/idea.2025.19>

ISBN: 978-91-7671-928-2 (PDF)

ISBN: 978-91-7671-929-9 (HTML)