Elections and Heatwaves: Philippines’ May 2025 Midterm General Elections

Case Study, January 2026

Executive summary

The 2025 Philippine national and local elections unfolded amid one of the country’s most prolonged and intense heatwaves on record. Between December 2024 and May 2025, heat indices in several regions reached ‘danger’ and ‘extreme danger’ levels of 42–47 °Celsius (°C). In this period, the Pangasinan, Bulacan and Metro Manila regions experienced high temperatures, which affected the operations and logistics of election management, campaigning and election day activities. Despite these unprecedented climatic conditions, the Philippine Commission on Elections (COMELEC) successfully administered polls across 93,000 precincts on 12 May 2025, recording an 83.4 per cent voter turnout—the highest for any midterm election in Philippine history.

This case study examines how COMELEC and partner agencies adapted election management practices to the extreme heat. It documents both the institutional resilience demonstrated by Philippine electoral authorities and the limits of existing risk-management frameworks, which have not yet systematically integrated climate-related or heat-specific hazards. Most contingency planning continues to prioritize floods, security threats or technology failures, leaving health-related and temperature-sensitive risks under-addressed.

The findings highlight the multidimensional character of ‘natural’ hazards in electoral contexts: while heatwaves are physical phenomena, their conversion into disasters stems from governance vulnerabilities—underscoring the United Nations Office for Disaster Risk Reduction (UNDRR) principle that there are ‘no natural disasters, only natural hazards interacting with social exposure and institutional weakness’ (UNDRR 2025). Additionally, the findings are supported by interviews with COMELEC officials at provincial and regional levels. While the extreme heat posed a challenge to the voters, poll workers and candidates, it ultimately did not unduly affect the election, because with the Philippines being a tropical country, stakeholders adapted and adjusted successfully.

The country’s 2025 experience demonstrates strong administrative performance but underscores the need to institutionalize climate adaptation. Key recommendations emerging from the Philippine case include:

- Integrate climate-risk management institutionally by formally embedding high temperatures and other climate hazards within COMELEC’s electoral risk-management framework and its resolutions governing election-periods;

- Leverage COMELEC’s constitutional and overarching mandate, deputizing any and all agencies of the State in pursuit of credible elections—to proactively mitigate heat and climate change-related issues;

- Adapt technical specifications of vote-counting machines (VCMs), ballots and other sensitive equipment to withstand higher temperatures and humidity;

- Develop data-driven early-warning and evaluation mechanisms linking temperature, turnout and incident reports—for example, to refine preparedness and guide resource allocation in future cycles; and

- Expand the use of ‘Register Anywhere’ to make voter registration more accessible and climate resilient. Continue expanding voting in shopping malls and other suitable climate-controlled places, which have proved beneficial to voters and polling staff.

Overall, the Philippine heatwave election of 2025 underscores that safeguarding electoral integrity in a warming world requires expanding the definition of ‘credible elections’ to include physical safety, health protection and climate resilience. Building on the country’s strong electoral administration, embedding climate-adaptive governance will be critical to ensuring that future elections remain not only peaceful and credible but also safe and sustainable.

Introduction

The Philippine Atmospheric, Geophysical, and Astronomical Services Administration (PAGASA) reports that temperatures in the country have increased by 0.68°C over half a century, or a warming rate of 0.1°C per decade. Depending on the model used, the projection is that average temperatures will rise by between 0.9°C and 2.4°C by the mid-21st century (PAGASA 2018). From December 2024 to May 2025, the Philippines experienced one of the longest and most intense heatwave periods in its history. PAGASA reported 69 days of climate-influenced extreme heat between December and February, extending into 163 days by late May 2025. Heat indices in several areas reached ‘dangerous’ levels (42–45°C), particularly affecting provinces in Northern Luzon, Metro Manila and parts of Visayas and Mindanao (Angelo 2025).

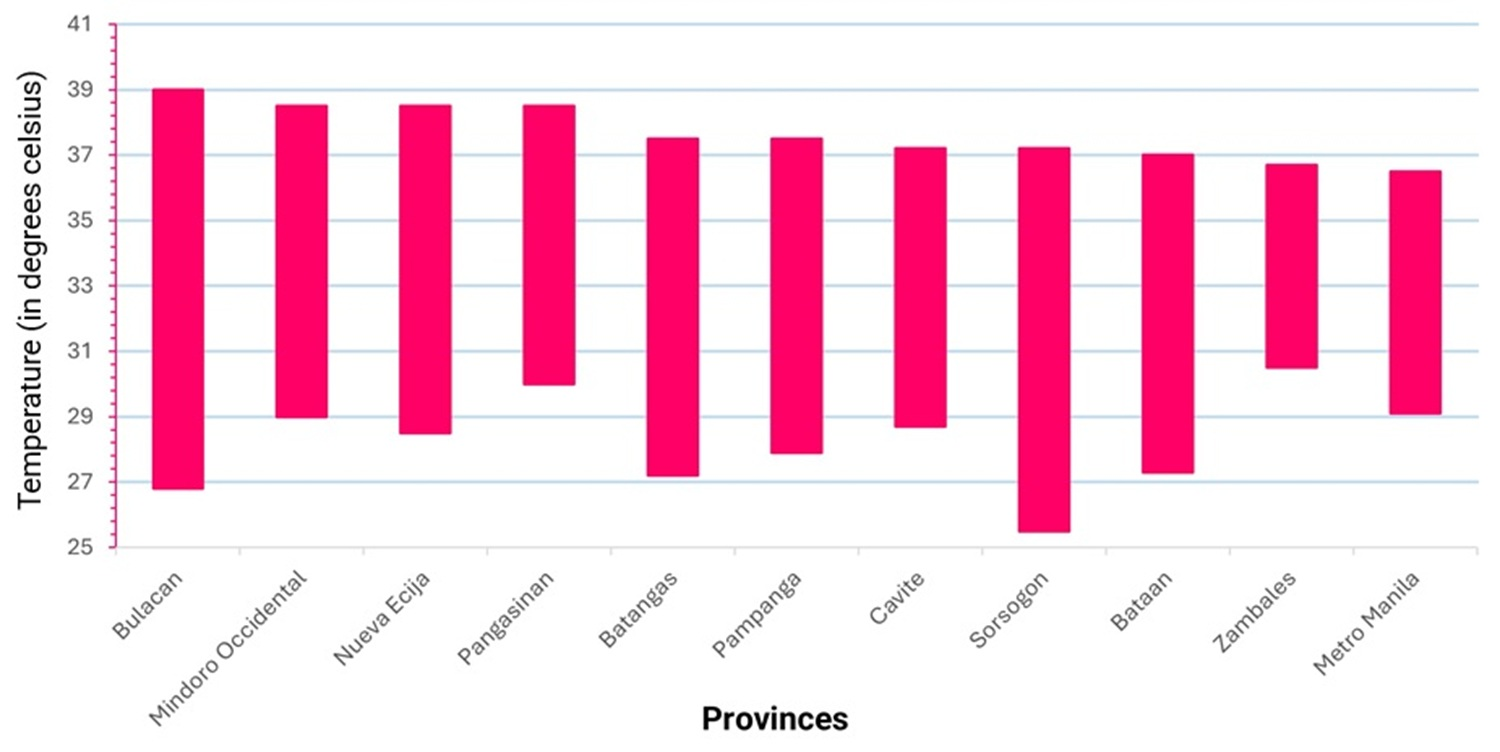

In 2025, the electoral campaign opened on 11 February and lasted until 10 May. In this period, some parts of the country saw maximum temperatures of between 35°C and 39°C, while the average maximum temperature throughout the country was 32°C. Heat indices in the two weeks leading up to the elections ranged from 42°C to 46°C in many parts, including heavily populated areas like the provinces of Bulacan and Pangasinan, and the Metro Manila area (GMA News 2025a,

This study will investigate the effects of high temperatures, a climate risk, on the personnel involved in the administration of the elections, focusing on the voter registration period and logistics—preparing and deploying equipment, supplies and materials; the campaign period; election day itself; and the few days after.

This report draws on key informant interviews with COMELEC officials from Bulacan, Pangasinan, and the National Capital Region (NCR) regional office, conducted in September 2025. Based on data obtained from PAGASA, Bulacan and Pangasinan recorded the highest temperatures and heat indices during the election period. While the NCR ranked 11th (of 81 provinces in the country) in recorded high temperatures and heat indices, it is important to this study as the most densely populated region in Southeast Asia (World Population Review 2025). According to the Philippine Statistics Authority (PSA), there are at least 14 million people in the NCR, 21,760 per square kilometer, half of whom are voters (PSA 2021). On election day, Bulacan experienced the highest temperatures, followed by heavy rain in the evening. In Pangasinan, the central area registered the highest temperature, while western and eastern parts were relatively cooler, with rain occurring in the western area later in the day.

Legal and institutional background

COMELEC is a permanent bureaucracy headed by a seven-member commission, akin to a company board. Operational staff are led by an executive director. The line functions are performed by regional election directors, provincial election supervisors, and city and municipal election officers. Highly populated urban areas, like those in the NCR, are divided into multiple congressional districts, each of which is assigned an election officer.

In an election year, COMELEC temporarily recruits over 370,000 polling station officials, primarily from the Department of Education, who are deployed to over 93,200 polling stations. Lawyers from the Department of Justice also render duty as members of the canvassing boards in each of the municipalities and cities (numbering over 1,600) and in the 81 provinces throughout the country. Police and other uniformed personnel provide security. In addition to providing security for election personnel, candidates and property, the Armed Forces of the Philippines provides to COMELEC its land, air and sea transport assets, such as ships and planes.

The Philippines holds elections every three years. As provided in the Constitution, elections take place every second Monday of May. A total of 18,320 posts nationwide were up for elections on 12 May 2025.

The Philippines has a mixed electoral system. The president and vice president are elected separately by plurality vote for a single six-year term with no re-election. Members of the Senate (24 seats) are elected nationwide using plurality-at-large voting (each voter can vote for up to 12 candidates, every three years for half of the Senate). Members of the House of Representatives are chosen through a mixed system—around 80 per cent by first-past-the-post in single-member districts and up to 20 per cent through party-list proportional representation for marginalized and sectoral groups (with a two per cent vote threshold and a three-seat cap per party). Governors, mayors and councilors are elected directly in their respective provinces, cities, and municipalities through a plurality vote.

COMELEC is a constitutionally-created body tasked with managing elections and similar exercises such as referendums and plebiscites. Its duties also cover the accreditation of political parties and individual candidacies. COMELEC also serves as an electoral court, a quasi-judicial function to decide ‘all questions affecting elections’ (Philippines 1987 art. IX-C, 1–2). As a constitutional body, it enjoys fiscal autonomy and is authorized to deputize any of the agencies of the government ‘with the concurrence of the President, law enforcement agencies and instrumentalities of the Government … for the exclusive purpose of ensuring free, orderly, honest, peaceful, and credible elections’ (Philippines 1987 art. IX-C, 1–2).

In practice, during the election period, the commission issues directives or memorandums (see, e.g. COMELEC 2024) to various government agencies to support its operations. These agencies include the Armed Forces of the Philippines, the Department of Interior and Local Government, the Philippine National Police, the Department of Education and the National Disaster Risk Reduction and Management Council (NDRRMC) (Philippines 2010).

Voters

Under the continuing incremental voter registration process, 69.7 million voters were registered to 93,287 polling stations throughout the country (COMELEC 2025b). Of these, 83 per cent (or 57.9 million voters) attended on election day in 2025, making this the highest turnout for a midterm election.

COMELEC also administers out-of-country voting, referred to as overseas absentee voting. Mostly done online, this covered 511 jurisdictions and countries. The process is administered through the Department of Foreign Affairs’ 93 embassies and consulates. The consulate in Italy, for example, handled voting for those in Milan and in eight other locations (Lombardia, Veneto, Trentino-Alto Adige, Friuli Venezia Giulia, Emilia Romagna, Valle d'Aosta, Piemonte and Liguria) (COMELEC 2025a).

1. Natural Hazards and Elections in the Philippines

July 2025 was the third-warmest July globally (after 2023 and 2024), with average sea surface temperature also the third highest on record (World Meteorological Organization 2025). In the Philippines, the heatwave in 2025 exceeded prior temperature records, particularly in March and April, when electoral campaigning and logistical preparations were in full swing (Tachev 2025). PAGASA recorded some of the highest temperatures in the country in April; most provinces with the highest temperatures were in the island of Luzon, where Bulacan, Pangasinan and the NCR are located.

March average temperatures already reached 34.6°C, and the heat index in parts of Luzon reached ‘danger’ levels ranging from 42°C to 51°C (Dito sa Pilipinas 2025). The highest previous recorded temperature for Metro Manila had been 36.6°C, with a heat index of 39°C, in 2019 (Magsino 2019). On 5 March 2025, a month into the election campaign period and two months before election day, the Philippine Red Cross put out alerts about potential heat-related emergencies (Philippine Red Cross 2025a). Based on rising heat indices, it warned the public of heat strokes and heat exhaustion and offered ways to avoid them.

The high temperatures recorded in Luzon are a result of its tropical location and weather patterns. Being situated near the equator, Luzon experiences consistently warm temperatures throughout the year. The island’s large size and diverse landscape, including mountain ranges and plains, also contribute to the range of temperatures experienced, with valleys and plains generally being hotter. The interplay of monsoon winds and its proximity to the ocean influences humidity levels, leading to high sensible temperatures, especially from March to May

| Province | Maximum highest temperature recorded/ date | Minimum highest temperature | Average highest temperature | Standard deviation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bulacan | 25 April—39.0 | 26.8 | 33.7 | 2.5 |

| Mindoro Occidental | 20 April—38.5 | 29.0 | 34.9 | 1.7 |

| Nueva Ecija | 22 April—38.5 | 28.5 | 34.2 | 2.4 |

| Pangasinan | 8 April—38.5 | 30.0 | 33.3 | 1.6 |

| Batangas | 21 April—37.5 | 27.2 | 33.3 | 2.3 |

| Pampanga | 20 April—37.5 | 27.9 | 33.7 | 2.2 |

| Cavite | 16 April—37.2 | 28.7 | 33.8 | 2.1 |

| Sorsogon | 16 March—37.2 | 25.5 | 30.8 | 2.0 |

| Bataan | 28 April—37.0 | 27.3 | 33.1 | 1.8 |

| Zambales | 16 May—36.7 | 30.5 | 32.9 | 1.2 |

| Metro Manila | 17 April—36.5 | 29.1 | 33.8 | 1.9 |

The Philippines will continue to experience rising temperatures, even during months that are usually characterized by milder conditions (PAGASA n.d.a; IPCC 2021). Mean temperatures are anticipated to rise by 0.9°C to 1.1°C in 2020 and by 1.8°C to 2.2°C by 2050. The highest temperature increase is expected during the summer season, March–May (PAGASA n.d.b). Particularly in elections that take place during the summer season, extreme heat is likely to affect voters, poll workers and electoral logistics.

Climate change can directly explain why extreme weather events, such as the prolonged and intense heat experienced in the Philippines between December 2024 and May 2025, have become more frequent and severe. According to a recent study of megacities, Manila has a Climate Shift Index (CSI) of 69 days, with average temperatures 0.4°C above normal (Climate Central 2025; see Table 2).

| Continent | Country | Megacity | Days at CSI 2 or higher | Seasonal temperature anomaly (C) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Africa | Nigeria | Lagos | 89 | 1.0 |

| Asia | India | Tamil Nadu | 81 | 1.0 |

| Asia | Philippines | Manila | 69 | 0.4 |

| Asia | Indonesia | Jakarta | 69 | 0.7 |

| Africa | Democratic Republic of the Congo (Kinshasa) | Kinshasa | 57 | 0.6 |

| North America | Mexico | Mexico City | 49 | 0.5 |

| Asia | India | Maharashtra | 36 | 1.2 |

| Asia | India | Telangana | 36 | 0.8 |

| South America | Brazil | Sao Paolo | 34 | 0.4 |

| Asia | Iran | Tehran | 34 | 1.6 |

| Asia | India | Karnataka | 31 | 0.7 |

Power supply

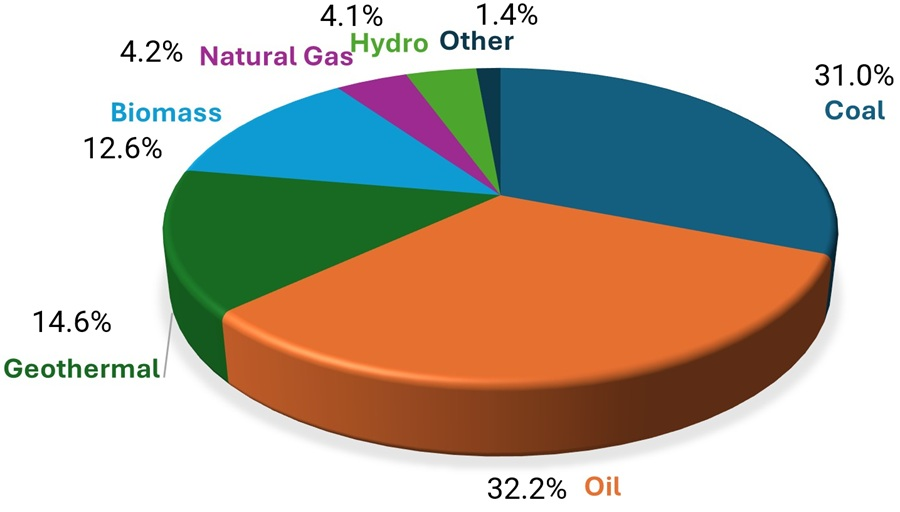

Availability of stable and uninterrupted power is critical in the administration of elections. The Department of Energy made this explicit in committing to ‘supporting the safe, orderly, and uninterrupted conduct of the elections by safeguarding the integrity of energy services throughout the voting, transmission, and canvassing periods’ (Deptartment of Energy 2025). The Philippine power supply is characterized by a fragmented grid system, with three main grids in Luzon, Visayas and Mindanao. While the Luzon and Visayas grids are interconnected by a high-voltage direct current line, the Mindanao grid remains largely isolated—hence the Mindanao-Visayas Interconnection Project is underway. This lack of complete interconnection presents challenges in terms of electricity costs, reliability and access, particularly for smaller islands (RTVM 2024).

The months of April, May and June typically experience peak demand due to increased electricity consumption for cooling purposes as temperatures rise

In its 2023–2050 plan, the Department of Energy elaborates the current energy mix as largely based on fossil fuels—oil and coal comprise over 60 per cent (Figure 3). Hydroelectric power, which supplies 4.1 per cent of the power requirements (Deptartment of Energy n.d.), is directly affected by the lack of water during hotter months.

In early March 2025, the Institute of Climate and Sustainable Cities (ICSC) issued a yellow alert for Luzon because of the surge in electricity demand and a significant reduction in supply due to forced outages of baseload power plants (ICSC 2025). A yellow alert signifies that the available power reserves are low, and the system is operating with a reduced margin to meet demand—potentially leading to power interruptions if there are any unexpected plant outages or increased demand. It warns that the system is vulnerable and proactive measures are needed to prevent a more serious situation (Esmael 2025).

In 2024, the National Grid Corporation of the Philippines (NGCP) issued 62 such yellow alerts, as well as 16 red warnings (Lagare 2024). However, on 5 March 2025, the general power supply situation had improved as Luzon was the only island of the country placed on yellow alert (Jose 2025). During the 2022 presidential and national elections, which were also held during a heatwave (Tan 2022), 201 brief and isolated power outages occurred at the municipal level (Crismundo 2022)—undermining voter experience and COMELEC’s capacity to uphold transparency and credibility. This is why in the 2025 elections, contingency plans were made to ensure a ‘brownout-free election’. The NGCP suspended all maintenance activity and ensured that all transmission lines were cleared of vegetation and other obstructions. It also assured the public that in case of power tripping on election day, line crews, engineers, pilots, maintenance and testing personnel, and other technical staff were positioned and ready to respond (Adriano 2025; Galang 2025).

While COMELEC operations can be affected by power outages, vote-counting machines are the least affected. This is because each machine has a battery that allows operations throughout and beyond the 12-hour voting period. This is a precautionary measure borne out of the fact that the power supply in the country is unevenly distributed and power outages could occur without warning.

2. The heatwave and the 2025 national elections

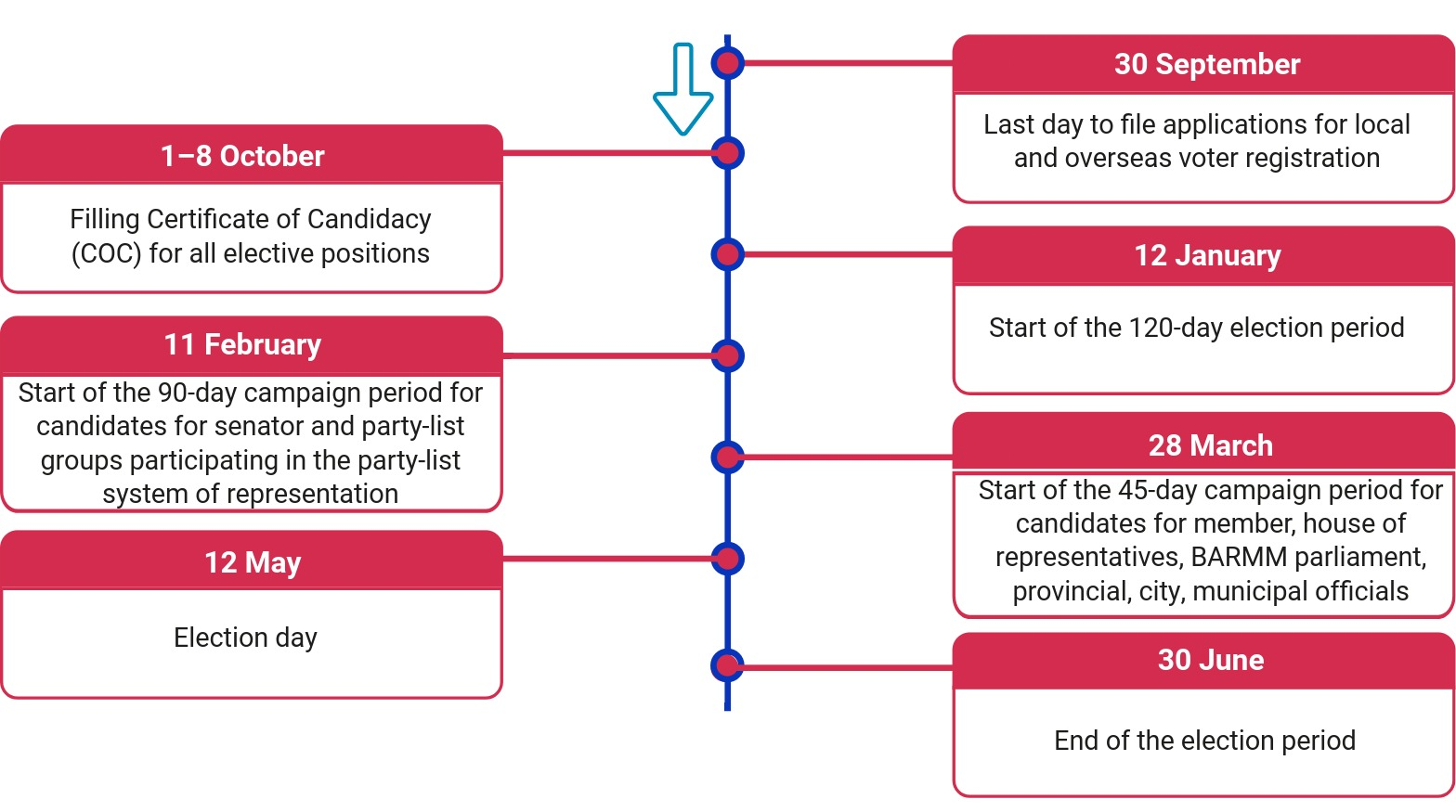

Candidates of national-level elective positions had a 90-day campaign period, while those for locally elected posts had 45 days. The beginning dates were 11 February and 28 March, respectively, both campaigns ending on 10 May (with a one-day silence period before the polls on 12 May) (see Figure 4 and Table 3). This period, when COMELEC’s logistical preparations were also fully underway, coincided with the highest maximum temperatures of the summer.

COMELEC’s activities during this period involved printing of the paper ballots, preparing and testing the thousands of vote-counting machines (VCM—also sometimes known as automated counting machines, ACM), and packing and shipping election materials. New polling officials needed training, and since the vote-counting machines for these elections were all new (from Miru Solutions of South Korea), all polling officials had to be trained to operate them.

The printing of official ballot papers was done within the National Printing Office premises using special paper sized for the vote-counting machines. On 15 March, COMELEC reported having printed all 68.54 million ballots (Sampang 2025b). All paper ballots then needed to be verified, a process where each is fed into a machine to check if it is readable. COMELEC reported that verification of the final batch of ballots designated for the National Capital Region, where the NPO is located, would be completed by 21 April (Sampang 2025b). COMELEC received its full order of 110,620 voting machines in late 2024. Based on the terms of the contract, each machine had to go through hardware acceptance tests and configuration. These were conducted at the COMELEC warehouse in Biñan City, Laguna. After completion and as early as a month before election day, COMELEC started shipping machines and other components to regional staging areas or hubs through a transport and logistics contractor. The machines would then be distributed to the polling centres in time for the schedule of the Final Testing and Sealing (FTS). During interviews for this report, COMELEC’s Offices of the Provincial Election Supervisors of Bulacan and Pangasinan, as well as with the NCR Regional Election Director, noted that although the extreme heat did not directly affect logistical operations, regional offices had taken their own precautionary measures (Laoc, Deseo and Jeung 2025; see Annex A for interview guide). For example, they ensured that vote-counting machines were placed in well-ventilated areas, and that training for election personnel was conducted in either air-conditioned venues or adequately ventilated spaces.

The Election Automation Law, also known as the Republic Act 9369 (Philippines 2007), requires COMELEC to test all vote-counting machines at the polling stations prior to their use to ensure functionality, readiness and accuracy. Between 2 and 12 May, this FTS was carried out nationwide (Republic of the Philippines 2007). The process involved polling station officials, and in some cases, candidates/representatives of political parties, election observers and the media. The representatives present were asked to fill out 10 test ballots which were then read by the machine, with the results verified against a printout. After verification, the results were transmitted to COMELEC’s remote servers and cross-checked. After the results were ascertained as correct and accurate, the machine would be sealed, to be unsealed only on election day, just before voting started.

On the day of FTS, the average maximum temperature recorded nationwide was 36.1°C (with a standard deviation of 0.79°C). While the ambient high heat might have caused discomfort among the participants, the FTS was done indoors in the polling stations (with just a few people inside) and did not appear to be affected by the heat.

3. Impact of heat on election management

Impact on voter registration

The Republic Act No. 8189, or Voter’s Registration Act, (Philippines 1996) provides for a system of continuing registration. All year round, citizens who will turn 18 years of age on or before election day may register by visiting the COMELEC office where they reside. Data shows that first-time voters in 2025, those aged between 17 and 20, comprise 6.22 per cent of the population or 4.25 million out of the 68.43 million in-country voters who were registered in 2025 (COMELEC 2025b).

The continuous voter registration process does not seem to have been much affected by the heatwave—or even by periods of heavy rain and typhoons in the second half of 2025. This is because those who want to register choose the day that is most convenient for them to visit the COMELEC office, where biometric information is submitted to complete the registration process. COMELEC has also deployed satellite voter registration centres outside its offices by collaborating with 170 malls, universities and other institutions nationwide to simplify and expand access

Before the 2025 elections, COMELEC further launched an online voter registration application system for in-country and out-of-country voters, called iRehistro (COMELEC 2023). Applicants provide all the necessary documentation online and personally attend COMELEC premises only to submit biometric information.

Impact on campaigning

Due to increasing temperatures and dangerously high heat indexes, typical campaign activities—rallies, motorcades and house-to-house visits under the hot sun—were more physically draining and carried increased risk of heat-related illnesses. Some campaigns installed air conditioning in open-air cars used in their motorcades as a health and safety measure (De Venecia 2025). The president of the Federation of Free Workers, who ran for the Senate, warned that ‘politicians must also encourage their campaign workers and volunteers to take the essential precautions—staying hydrated, wearing protective clothes, taking breaks in shaded areas, and changing schedules to avoid high heat hours’ (Ordonez, Atienza and Hufana 2025).

| National elective positions | Campaign period |

|---|---|

| Senators | 11 February to 10 May 2025 |

| Part-list representatives to congress | |

| Local elective positions | Campaign period |

| Governor | 25 March to 10 May 2025 |

| Vice-governor | |

| Provincial councilors | |

| District representative to congress | |

| Mayor | |

| Vice-mayors | |

| City or municipal councilors |

The Office of Civil Defense issued a Memorandum No. 66, s. 2025, urging local disaster risk reduction agencies as well as the management councils (DRRMCs) to prepare for the coming heatwave and its implications for heat exhaustion and heat stroke. The memo instructed the body’s regional directors to coordinate with national and local agencies to continuously monitor the conditions through the NDRRMC dashboard, stock protective gear and medical supplies, and ensure that they had vehicles readily available for deployment (De Leon 2025).

Those who live in warmer climates recognize the need to avoid outdoor activities during the warmest hours of the day. Traditional farming practices, still practiced today, reflect this wisdom: farmers who use cows and carabaos (water buffalo) often start plowing fields at early light and stop at 10:00, resuming work only after the temperature begins to cool in the afternoon. COMELEC officials noted that the campaign schedules proposed by contestants for its approval took place in the morning and late afternoons into early evening. Campaign events were generally held indoors in covered courts or gyms. There was no fixed schedule for house-to-house campaigning, as the candidates adjusted their activities depending on the heat.

Impact on logistics–Voter Information Sheet

COMELEC is required by the Republic Act 7904 to furnish each voter with a Voter Information Sheet (VIS) with the voter's personal details and simplified instructions as to the casting of votes: ‘The names of the candidates shall be listed in alphabetical order under their respective party affiliation and a one-line statement not to exceed three (3) words of their occupation or profession’ (Philippines 1995).

COMELEC encouraged voters to use the VIS to note down their choices of candidates and refer to it at the polling station when they vote. The distribution of the VIS was done through a third party, the contract being awarded through a local-level bidding process. A COMELEC provincial official noted that some parties refused to bid, citing the heat and the amount of work required for the distribution to be done all day, even at midday. In places where COMELEC could not find a suitable contractor, it asked village officials to help distribute the VIS.

Impact on logistics–Vote-Counting Machines

Since 2010, COMELEC has used machines to read and count votes marked on specially printed paper ballots. The internationally sourced machines, which use optical mark reader technology, are deployed in each polling station throughout the country. In 2025, a total of 127,000 such machines were purchased, 27 per cent of which served as back-up or replacement.

Since the VCMs used in 2025 were procured from a new supplier, almost 190,000 polling staff had to undergo training. Starting in March, municipal-level training of polling officials was held throughout the country (Sampang, 2025a). According to COMELEC officials, training sessions took place indoors, sometimes in hotels and similar establishments where the temperature was controlled or made more bearable through the use of cooling fans. None of the COMELEC officials interviewed cited heat as a factor that interfered with the training.

As early as in the third quarter of 2024, COMELEC conducted a national roadshow where the VCM and its features were introduced and demonstrated to the public—in schools, malls and other public areas. COMELEC respondents described the roadshows as a real-life ‘stress test’ for the VCMs’ operating environment. The machines were subjected to the rigours of being transported—from rough mountainous terrain to water crossings to extreme heat and damp conditions. Many hardware sensitivities were identified, enabling COMELEC to remedy these before election day. COMELEC specified conditions under which the machines were to be stored, such as well-ventilated warehouses or other locations. When finally delivered to the polling location (usually a school), they were likewise kept in well-ventilated rooms.

Impact on election day and run-up

On 27 March, COMELEC, the Department of Health, the Department of Interior and Local Government (DILG) and the Philippine Red Cross entered into a memorandum of agreement that aimed ‘to ensure that voters and persons rendering election-related services have easy access to free first-aid assistance, medicine, and emergency medical services during the 2025 national and local elections … and every election thereafter’. This alliance of organizations encouraged city and municipal governments to set up a health station or similar in all voting centres ‘with necessary resources, essential medicines, and an ambulance to provide free, timely, and effective first-aid assistance’ (DILG 2025b). While climate risks were not mentioned in the agreement, awareness of heat-related health issues was among the reasons for making health services readily available during polling.

PAGASA warned voters to take precautionary measures against heat-related illnesses on election day, noting that 28 areas across the country could expect extreme heat (PAGASA 2025). PAGASA placed several areas under the ‘danger’ classification with a forecast heat index ranging from 42°C to 45°C (Laqui 2025). PAGASA urged voters to avoid queuing during the peak heat hours of 10:00 to 15:00 to wear light clothing and to stay hydrated (Eguia 2025). Among those vulnerable to heat-related illness were seniors aged 60 and above, who comprised 16.8 per cent (11.7 million) of the registered voters (COMELEC 2025c, 2025f).

On election day itself, the Department of Health posted a reminder to voters to be ‘vigilant against heat-related illnesses … and to take basic precautions to protect their health while lining up and casting their ballots’ (Santos 2025). Citing data and the ‘danger level’ warning from PAGASA, the Department of Health advised the public to wear light clothing and keep themselves hydrated (Montemayor 2025).

As expected, health issues attributed to high heat were reported on election day. In the town of Tulunan in Cotabato province, six people collapsed while queuing to vote. At least 10 voters were brought to the medical tent inside the school after complaining of unease, which was later found to be caused by high blood pressure. On that day, the temperature in the municipality was 37°C (Magbanua 2025).

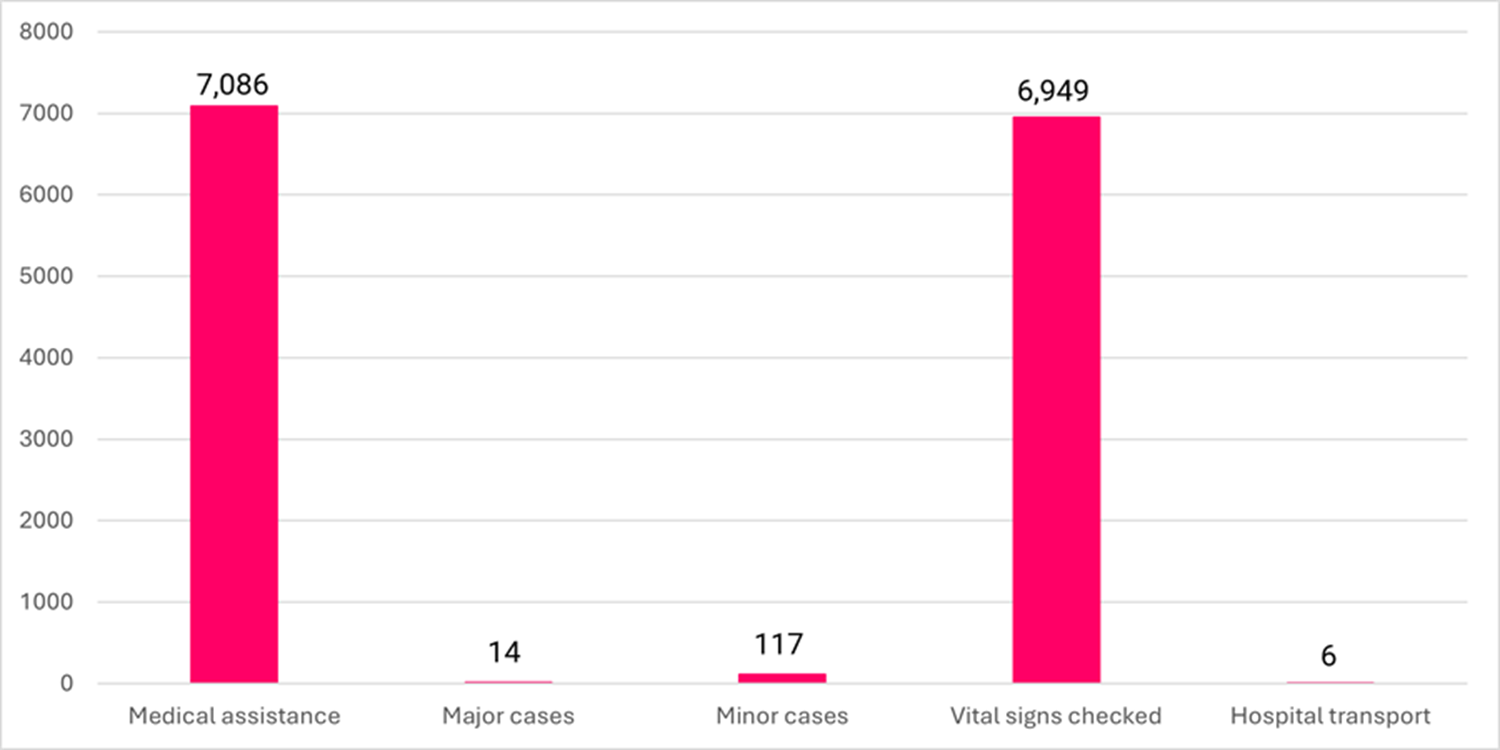

In Oas, Albay, a 65-year-old man felt dizzy inside the polling station in Central School; shortly after voting, he collapsed and died. According to the Bicol Police Regional Office, heat was the likely cause (Ogerio 2025). Nationwide, the Red Cross recorded heat-related incidents involving 11,531 people

According to the COMELEC officials interviewed, voters themselves took practical precautions and chose a more convenient time to go to the polling station. Some waited until the sweltering heat eased, while others purposely braved the midday heat, knowing that queues would be shorter at those times. Depending on the population of the village, the size and location of the school building (as polling station), queues could spill out of the school premises and snake into the street, exposing voters directly to the hot sun (see Figure 6).

Polling staff noted that the long queues started to ease at 10:30 as the temperature rose. On past experience they expected that queues would build again from 15:00 when the heat recedes (

As a precautionary measure against overcrowding, COMELEC officials specified that polling stations within school premises must not be adjacent to each other. They selected well-ventilated classrooms and in some cases pitched tents to provide shade to voters waiting for their turn to vote. Other agencies, particularly local government units, were requested to help with cooling fans and water dispensers to place in the holding areas. Ventilation of the holding areas was critical because while it took on average 10 minutes for a voter to complete the process; the wait time could be longer because polling stations were set up to take only a maximum of 10 voters at any given time. The maximum number limit is determined more by the size of the classrooms—typically 63 square metres—than by any other factor.

On the whole, the NDRRMC situational report noted that the extreme heat and associated risks had been given utmost consideration, with various agencies and local government units preparing contingency plans to address them (NDRRMC 2025). This represents a significantly raised awareness of climate risk, including as it affects elections.

The ‘game changers’ in mitigating this risk, according to COMELEC, were early hours of voting and voting in the malls. In highly urbanized and densely populated areas, school buildings are clustered among other buildings, which reduces natural aeration and therefore requires ventilation from cooling fans. But under ambient high heat, these fans could not do much except to move hot air around. To help address this, COMELEC designated 42 malls throughout the country as polling centres, in agreement with owners. Voters registered at nearby polling stations could cast their votes at these new venues.

Early voting hours voting was arranged from 05:00 to 07:00, when the sun is still low, exclusively for pregnant women, the elderly and persons with disabilities. Regular voting would then continue from 07:00 until 19:00. COMELEC also provided Accessible Polling Places (APPs) on the ground floor of each polling center, ideally near the building's entrance. APPs are free of physical barriers and provide all essential services, including assistive equipment. Emergency Accessible Polling Places, meaning rooms or tents installed on the ground floor of multilevel polling facilities, were intended to make voting easier for people with disabilities, senior citizens and pregnant women (COMELEC 2025d art.1).

Vote-counting machines (VCMs)

The COMELEC and polling officials reported malfunctioning of some machines, which they attributed to internal heat buildup caused in part by high ambient temperatures. At the New Era Elementary School polling centre in Quezon City, Metro Manila, overheated machines ejected ballots that they had previously accepted (Antalan 2025). In past elections, polling officials reportedly directed cooling fans at the VCMs, suspecting heat was the reason for malfunctions; such incidents were noticeably fewer in 2025, aided by improved knowledge of machine operation among many polling staff.

The procedure for rejected ballots is stated in Section 46 of Resolution 11076 General Instructions for Voting, Counting, and Transmission of Results. If the VCM screen displays the ‘Misread Ballot’ message, the voter is allowed to re-feed the ballot paper in four different orientations (COMELEC 2024). This means flipping the paper on the long side and on the short side until it is accepted by the machine.

COMELEC assured the public that the ink (applied on voters’ fingers to indicate that they had already cast their votes) was ‘not expired’, and ‘any change in their colour or effectiveness may have been caused by the unusually high temperatures on election day’ (Antalan 2025). This would warrant a determination of the heat sensitivity and photosensitivity of silver nitrate, on which (indelible) election ink is based and also whether COMELEC’s specifications for bidders/suppliers, including packaging, are adequate for hot conditions.

4. Voter turnout

Voter interest in Philippine elections in 2025 was characteristically and comparatively high. The average turnout in presidential elections is 79.2 per cent, and in midterm elections, it is 77.7 per cent. The number of registered voters had increased by 12.78 per cent since 2019—from 61.8 to 69.7 million in 2025. Turnout in these midterm elections was 83.4 per cent, compared with 79.5 per cent in 2022 (presidential) and 83.4 per cent in 2019 (midterms). The reasons for high turnout are as follows:

First, with all positions (except for president and vice-president) contested, midterms involve a flurry of activity to drum up interest among voters. Elections are generally described as ‘festive’. The long campaign season of 90 days adds to the ubiquity of campaigns events, campaign posters and political advertising on various media—making it impossible for anyone to ignore the elections. Election day is a public holiday, held on a Monday, and thus a long weekend.

| Presidential | Mid-term | |

| Average | 97.2% | 77.7% |

| Std dev | 3.6% | 3.8% |

| Year | Type of election | Turnout |

| 2025 | Mid-term | 83.1% |

| 2022 | Presidential | 82.6% |

| 2019 | Mid-term | 74.3% |

| 2016 | Presidential | 80.7% |

| 2013 | Mid-term | 75.8% |

| 2010 | Presidential | 74.3% |

Second, COMELEC pursues enfranchisement of all who are qualified to vote. To its credit, the commission has made significant efforts through assertive and accessible voter registration in- and out-of-country; improving access to Indigenous communities, persons deprived of liberty (prisoners who are qualified to vote) and the ‘vulnerable sector’ (senior citizens, persons with disabilities and pregnant women); and making voting easier via the internet and at malls.

Third, the use of the VCMs has increased public acceptance of the election results, stating in a report on the 2022 elections by the Carter Center, ‘the use of VCMs is widely accepted by voters’ (The Carter Center 2024, p. 22). Previously, manual counting took between two weeks and one month for votes to be consolidated and reported—a delay in which doubts about the integrity of systems could circulate. Now, results start to come in as early as one hour after polling closes, and by morning the following day, almost all results are already known.

Table 5 compares the number of voters in the 2019 and 2025 midterm elections in NCR (column 2), which show a net increase of 7.1 per cent, with a standard deviation of 18.2 per cent. The comparative turnout in these two elections (column 3) also showed a net increase of 9.1 per cent, with a standard deviation of 4.6 per cent.

| City in the National Capital Region | Increase/decrease in voters (%) | Increase/decrease in turnout (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Las Piñas | -3.0 | 16.6 |

| Muntinlupa | -7.8 | 13.6 |

| Caloocan | 6.4 | 13.6 |

| Mandaluyong | -2.5 | 12.3 |

| Manila | 7.2 | 12.2 |

| Taguig-Pateros* | 50.4 | 11.1 |

| Quezon City | 9.3 | 10.6 |

| Malabon | 5.2 | 10.2 |

| Pasay City | 2.5 | 8.9 |

| Parañaque | 7.4 | 8.6 |

| Marikina | 28.4 | 7.8 |

| Makati* | -40.3 | 6.9 |

| Pasig | 5.2 | 6.7 |

| Valenzuela | 16.0 | 6.2 |

| Navotas | 7.7 | 3.3 |

| San Juan | 21.3 | -3.5 |

Comparing the number of voters in 2019 and 2025 in the most populous provinces (Table 6), voter registration went up by an average of 10.6 per cent, with a standard deviation of 3.9 per cent. The comparative turnout showed 6.0 per cent more voters participated (with a standard deviation of 1.6 per cent) in 2025 compared to the previous midterm elections in 2019.

| Top 20 provinces with the most voters | Increase/decrease in voters (%) | Increase/decrease in turnout (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Cebu | 10.5 | 4.6 |

| Cavite | 13.9 | 8.5 |

| Pangasinan | 10.8 | 6.4 |

| Laguna | 12.5 | 5.0 |

| Negros Occidental | 6.0 | 7.5 |

| Bulacan | 16.6 | 6.8 |

| Batangas | 14.1 | 8.1 |

| Rizal | 3.1 | 8.1 |

| Iloilo | 8.2 | 5.1 |

| Nueva Ecija | 10.9 | 7.3 |

| Pampanga | 14.7 | 6.5 |

| Davao del Sur | 4.4 | 3.5 |

| Leyte | 8.4 | 5.4 |

| Quezon | 16.5 | 6.2 |

| Camarines Sur | 12.0 | 3.9 |

| Zamboanga del Sur | 7.9 | 3.0 |

| Isabela | 7.1 | 6.2 |

| Misamis Oriental | 14.1 | 5.1 |

Comparing the turnout in the 2019 and 2025 elections in the top 20 provinces where the highest 2025 temperatures were recorded (Table 7) showed a similar average increase in turnout of 6.3 per cent, with a standard deviation of 1.9 per cent.

| Provinces (in order of highest temperatures recorded) | 2025 Turnout (%) | Increase/decrease vs. 2019 elections (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Bulacan | 85.0 | 6.8 |

| Occidental Mindoro | 79.6 | 3.6 |

| Nueva Ecija | 83.3 | 7.3 |

| Pangasinan | 86.8 | 6.4 |

| Batangas | 86.7 | 8.1 |

| Pampanga | 84.7 | 6.5 |

| Cavite | 78.6 | 8.5 |

| Sorsogon | 85.9 | 5.2 |

| Bataan | 84.5 | 5.8 |

| Zambales | 83.2 | 6.4 |

| Ilocos Norte | 89.0 | 6.5 |

| Samar | 80.4 | -0.3 |

| Eastern Samar | 86.1 | 6.7 |

| Zamboanga del Sur | 84.6 | 6.0 |

| Davao del Sur | 81.9 | 6.7 |

| Cotabato | 84.6 | 7.5 |

| Cagayan | 85.8 | 8.5 |

| Palawan | 84.0 | 7.6 |

| Ilocos Sur | 88.8 | 5.5 |

| South Cotabato | 84.1 | 6.7 |

5. Conclusion and recommendations

The 2025 Philippine general elections unfolded during one of the longest and most intense heatwave periods in recent history. Protecting elections under these conditions required coordinated, multilayered safeguards aimed at ensuring both electoral integrity and public safety.

COMELEC’s mandate to access the machinery and resources of the state in support of holding credible elections allows it to mitigate and address risks. In a whole-of-government approach, COMELEC is thus able to optimize resources and provide synergy in its responses down to the local level, including the removal of bureaucratic hurdles normally associated with nationally centralized agencies. While flooding and fire were among the scenarios that COMELEC had identified in its risk planning, extreme heat was not. Many areas in the country are prone to flooding aggravated by high tides, for example in the province of Bulacan where flood preparations were put in place. In this case, the Election Coordination Committee (spearheaded by COMELEC) included the Provincial Disaster Risk Reduction and Management Office; the Health Department, including the village-level health staff; the provincial Department of Local Government, which included police; the Bureau of Fire Prevention; the privately owned power utility; and others.

While general risk management is well developed, the 2025 elections thus revealed both the urgency and feasibility of embedding climate resilience into electoral governance. In the short term, several fixes can be mainstreamed into election operations within the next three years. These include standardizing health and safety measures at polling places—such as hydration points, first-aid posts and ambulance access—so that such provisions are not improvised but mandated. Clear communication with voters, polling officials and contestants on safe voting hours, protective clothing and other heat precautions should also become routine practice.

Expanding the use of climate-controlled venues (such as malls) and early-hours voting appears a feasible way to reinforce protection for voters and polling staff. Just as importantly, specifications for VCMs to be able to operate in high or higher temperatures and humidity (above the usually stated maximum operating temperature of 40°C) might need to be put in place.

The COMELEC officials interviewed for this paper cited microclimates—the differing temperature conditions within a province. Thus, different mitigating measures would also be required. The authors recommend that COMELEC issue a policy that supports the current setup, similar to the Election Coordinating Committee in Bulacan, but to authorize its local officials to institute appropriate measures to address risks such as those associated with extreme heat. The limits to forecasting microclimates is due to the relatively small number of weather sensors serving PAGASA—59 weather stations in 45 (of the 81) provinces. As weather patterns become more varying and unpredictable, local governments, such as the municipalities, might see the need to have their own weather sensors. COMELEC would then be able to use these to activate locally tailored measures based on heat triggers.

It would be incumbent on COMELEC to develop data-driven early-warning and evaluation mechanisms linking temperature, turnout and incident reports to refine its preparedness and guide resource allocation in future election cycles.

National (civil society) election observers play a prominent role in Philippine elections, particularly on election day. These could set up Voter Assistance Desks in polling centres to provide voting-related information and help voters locate their precincts. They could also provide advisories to voters, especially those queuing outside the polling stations, on precautions and mitigation measures. The more they are involved in this, the more likely they are to be consulted on improving heat mitigation measures more widely.

A longer-term reform, but one that could be initiated right away, is to make public schools—the backbone of COMELEC’s polling station network, but owned and maintained by the Department of Education—more climate-resilient. The Department could make thermometers standard equipment in schools and have thermal standards and appropriate warnings and remedies during hot conditions. This could become a standard for COMELEC to follow in operating polling stations on election day.

Internet voting was successfully piloted for the first time for overseas voters in the 2025 elections. Enabling the ‘ballot going to the voter’ as opposed to the ‘voter going to the ballot’, internet voting may be more resilient to climate risk, a factor to weigh in considering its expansion.

Regarding voter registration, from 1–10 August 2025, COMELEC pilot-tested the ‘Register Anytime, Anywhere’ programme—a system whereby voter registration could be conducted in selected hospitals, call centres, air and other transport terminals and other public places (Patinio 2025). Here again, roll-out of the change would make processes not only more accessible and convenient but also more resilient to climate-related events.

Summary of recommendations

The 2025 experience demonstrates the need to institutionalize climate adaptation:

- Integrate climate-risk management institutionally by formally embedding high-tempratures and other climate hazards within the COMELEC’s electoral risk management framework and its resolutions governing election-periods;

- Leverage COMELEC’s constitutional and overarching mandate deputizing any and all agencies of the state in pursuit of credible elections—to proactively mitigate heat and climate change-related issues;

- Adapt technical specifications of VCMs, ballots and other sensitive equipment to withstand higher temperatures and humidity;

- Develop data-driven early-warning and evaluation mechanisms linking temperature, turnout and incident reports, for example, to refine preparedness and guide resource allocation in future cycles; and

- Expand the use of ‘Register Anywhere’ to make voter registration more accessible and climate resilient. Continue expanding voting in shopping malls and other suitable climate-controlled places, which have proved beneficial to voters and polling staff.

References

Abello, L. T., ‘It’s too hot! Why some areas in the Philippines have hotter temperatures’, Manila Bulletin, 18 April 2024, <https://mb.com.ph/2024/4/18/it-s-too-hot-why-some-areas-in-the-philippines-have-hotter-temperatures-1>, accessed 6 November 2025

Adriano, L., ‘NGCP implements contingency measures for May 12 polls’, Philippine News Agency, 9 May 2025, <https://www.pna.gov.ph/articles/1249754>, accessed 6 November 2025

Angelo, F. A. L., ‘PHL endures extreme heat as climate change intensifies’, Daily Guardian, 24 March 2025, <https://dailyguardian.com.ph/phl-endures-extreme-heat-as-climate-change-intensifies/#google_vignette>, accessed 6 November 2025

Antalan, M., ‘COMELEC blames extreme heat for ballot ejection from counting machines’, DZRH, 12 May 2025, <https://dzrh.com.ph/post/comelec-blames-extreme-heat-for-ballot-ejection-from-counting-machines>, accessed 6 November 2025

Ateneo De Manila, ‘COMELEC Register Anywhere Project held onsite at Ateneo’, 29 April 2024, <https://www.ateneo.edu/news/2024/04/29/comelec-register-anywhere-project-held-onsite-ateneo>, accessed 6 November 2025

Baclig, C. E., ‘Explainer: Voter registration for 2025 elections’, Inquirer.net, 25 September 2024, <https://newsinfo.inquirer.net/1986839/explainer-voter-registration-for-2025-elections>, accessed 6 November 2025

Carter Center, ‘Philippines final report’, 2024, <https://www.cartercenter.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/03/philippines-final-report-050922.pdf>, accessed 27 November 2025

Climate Central, People exposed to climate change: December 2024–February 2025 (Princeton, NJ: Climate Central, 2025), <https://www.climatecentral.org/report/people-exposed-to-climate-change-dec2024-feb2025>, accessed 6 November 2025

Commission on Elections, Republic of the Philippines, ‘iRehistro’, 16 October 2023, <https://comelec.gov.ph/?r=VoterRegistration/iRehistro>, accessed 8 November 2025

—, ‘Resolution No. 11055’, 13 September 2024, <https://comelec.gov.ph/php-tpls-attachments/2025NLE/Resolutions/com_res_11055.pdf>, accessed 8 November 2025

—, ‘2025 NLE Specific Modes of Overseas Voting (Final)’, 5 February 2025a (amended 15 January 2025), <https://comelec.gov.ph/?r=OverseasVoting/2025_EOV/2025NLESpecificModesOfOverseasVoting/02052025_2025NLE_SMOV_FINAL>, accessed 8 November 2025

—, ‘Statistics’, updated 25 March 2025b, <https://comelec.gov.ph/?r=2025NLE/Statistics>, accessed 8 November 2025

—, ‘Data on the number of registered voters by single year age and sex [spreadsheet]’, 12 May 2025c, <https://docs.google.com/spreadsheets/d/1VpGsCoOb7Wt6PLmiDf5V3ljuSLuKjToc7B1tc-IjXDs/edit?usp=sharing>, accessed 26 November 2025

—, ‘Resolution No. 11076’, 12 May 2025d, <https://comelec.gov.ph/php-tpls-attachments/2025NLE/Resolutions/com_res_11076.pdf>, accessed 26 November 2025

Crismundo, K., ‘201 brief power interruptions reported on Election Day’, Philippine News Agency, 9 May 2022, <https://www.pna.gov.ph/articles/1174024>, accessed 6 November 2025

—, ‘DOE urges consumers to save power for summer’, Philippine News Agency, 13 March 2023, <https://www.pna.gov.ph/articles/1197261>, accessed 6 November 2025

De Leon, J., ‘Local DRRMCs asked to prep for heat wave’, SunStar, 5 March 2025, <https://www.sunstar.com.ph/pampanga/local-drrmcs-asked-to-prep-for-heat-wave>, accessed 6 November 2025

Department of Energy, ‘DOE mobilizes energy sector to ensure uninterrupted power for 2025 National and Local Elections’, 5 May 2025, <https://legacy.doe.gov.ph/press-releases/doe-mobilizes-energy-sector-ensure-uninterrupted-power-2025-national-and-local>, accessed 6 November 2025

—, ‘Philippine energy plan 2023–2050’, [n.d.], <https://legacy.doe.gov.ph/pep>, accessed 6 November 2025

Department of the Interior and Local Government (DILG), ‘Memorandum Circular No. 2025-046’, 2025, <https://dilg.gov.ph/PDF_File/issuances/memo_circulars/dilg-memocircular-202559_e8ca6a872c.pdf>, accessed 17 August 2025

De Venecia, J. C., ‘Battling the scorching heat’, Manila Bulletin, 8 March 2025, <https://mb.com.ph/2025/3/8/battling-the-scorching-heat>, accessed 6 November 2025

Dito sa Pilipinas, ‘March 2025 sees Record-Breaking Heat’, [n.d.], <https://ditosapilipinas.com/national/news/article/03/11/2025/march-2025-record-breaking-heat/1402>, accessed 12 August 2025

Eguia, A. D., 'Warm, humid weather expected on Election Day,' Daily Tribune, 11 May 2025, <https://tribune.net.ph/2025/05/11/warm-humid-weather-expected-on-election-day>, accessed 6 November 2025

Esmael, L. K., ‘NGCP puts Visayas, Mindanao power grids on “Yellow Alert”’, Inquirer.net, 1 August 2025, <https://business.inquirer.net/538844/ngcp-puts-visayas-mindanao-power-grids-on-yellow-alert>, accessed 6 November 2025

Galang, G. C., ‘NGCP halts substation maintenance, clears lines ahead of 2025 elections’, Manila Bulletin, 8 May 2025, <https://mb.com.ph/2025/05/08/ngcp-halts-substation-maintenance-clears-lines-ahead-of-2025-elections>, accessed 6 November 2025

GMA News, ‘“Danger level” heat index predicted for 5 areas on Friday, April 11, 2025’, 10 April 2025a, <https://www.gmanetwork.com/news/scitech/weather/942331/danger-level-heat-index-predicted-for-5-areas-on-friday-april-11-2025/story/>, accessed 6 November 2025

—, ‘“Danger level” heat index to hit 26 areas on Tuesday, April 22, 2025’, 21 April 2025b, <https://www.gmanetwork.com/news/scitech/weather/943455/danger-level-heat-index-to-hit-26-areas-on-tuesday-april-22-2025/story/>, accessed 13 November 2025

Independent Electricity Market Operator Philippines (IEMOP), ‘Average Electricity Prices Expected To Remain Stable In Q4’, 2024, <https://www.iemop.ph/2024/?post_type=news#:~:text=The%20Luzon%20region%20recorded%20an,6.63%20PhP/kWh%20in%20April>, accessed 6 November 2025

Institute for Climate and Sustainable Cities (ICSC), ‘ICSC: Luzon’s first yellow alert in 2025 warns of more grid alerts this dry season’, 7 March 2025, <https://icsc.ngo/icsc-luzons-first-yellow-alert-in-2025-warns-of-more-grid-alerts-this-dry-season/>, accessed 6 November 2025

Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), ‘Climate change widespread, rapid, and intensifying’, 9 August 2021, <https://www.ipcc.ch/2021/08/09/ar6-wg1-20210809-pr/>, accessed 6 November 2025

Jose, A. E., ‘Power failure threatens integrity of May 12 Philippine elections’, Business World, 8 May 2025, <https://www.bworldonline.com/the-nation/2025/05/08/671481/power-failure-threatens-integrity-of-may-12-philippine-elections/>, accessed 6 November 2025

Joviland, R., ‘PH Red Cross: Over 7,000 patients sought medical aid on Election Day’, GMA News,13 May 2025, <https://www.gmanetwork.com/news/topstories/nation/946007/ph-red-cross-over-7-000-patients-sought-medical-aid-on-election-day/story/>, accessed 6 November 2025

Lagare, J. B., ‘Nationwide red, yellow alerts raised as power supply thins’, Inquirer.net, 24 April 2024, <https://business.inquirer.net/456089/nationwide-red-yellow-alerts-raised-as-power-supply-further-thins>, accessed 6 November 2025

Laoc, T., Deseo, L. and Jeung, Y., ‘Key informant interviews with COMELEC Offices of the Provincial Election Supervisors of Bulacan and Pangasinan, and the NCR Regional Election Director, conducted for this report’, 2025, unpublished interviews

Laqui, I., ‘Heat index hits 45°C in parts of Philippines on Election Day’, Philstar.com, 12 May 2025, <https://www.philstar.com/headlines/weather/2025/05/12/2442535/heat-index-hits-45c-parts-philippines-election-day>, accessed 6 November 2025

Magbanua, W., ‘6 voters collapsed due to heat in Cotabato town precinct’, Enquirer.net, 12 May 2025, <https://www.inquirer.net/442069/6-voters-collapsed-due-to-heat-in-cotabato-town-precinct/>, accessed 6 November 2025

Magsino, D., ‘Metro Manila records its hottest temperature in 2019 at 36.6°C’, GMA News, 21 April 2019, <https://www.gmanetwork.com/news/scitech/weather/691920/metro-manila-records-its-hottest-temperature-in-2019-at-36-6-deg-c/story/>, accessed 6 November 2025

Mier-Manjares, M. A., ‘Elderly voter dies after casting ballot in Albay’, Inquirer.net, 12 May 2025, <https://www.inquirer.net/441753/elderly-voter-dies-after-casting-ballot-in-albay/>, accessed 6 November 2025

Montemayor, M. T., ‘DOH: Be alert amid “danger” level heat index’, Philippine News Agency, 12 May 2025, <https://www.pna.gov.ph/articles/1249875>, accessed 6 November 2025

Ogerio, B. A., ‘Scorching heat, scattered rains mark Election Day – PAGASA’, BusinessMirror, 12 May 2025, <https://businessmirror.com.ph/2025/05/12/scorching-heat-scattered-rains-mark-election-day-pagasa/>, accessed 6 November 2025

Ordonez, J. V., Atienza, K. A. and Hufana, C. M., ‘Philippine gov’t crafting contingency plan amid extreme heat, says palace’, Business World, 3 March 2025, <https://www.bworldonline.com/the-nation/2025/03/03/656841/philippine-govt-crafting-contingency-plan-amid-extreme-heat-says-palace/>, accessed 6 November 2025

Patinio, F., ‘Comelec trial of “Register Anytime, Anywhere” program set in August’, Philippine News Agency, 10 July 2025, <https://www.pna.gov.ph/articles/1254032>, accessed 6 November 2025

Peña, K. D., ‘43°C heat alters voting behavior in many areas’, Inquirer.net, 12 May 2025, <https://www.inquirer.net/442128/45-degree-celsius-heat-alters-voting-behavior-in-many-areas/>, accessed 6 November 2025

Philippine Atmospheric, Geophysical and Astronomical Services Administration (PAGASA), Observed and projected climate change in the Philippines (Quezon City: PAGASA, 2018), <https://icsc.ngo/wp-content/uploads/2019/07/PAGASA_Observed_Climate_Trends_Projected_Climate_Change_PH_2018.pdf>, accessed 6 November 2025

—, ‘Climatological data: maximum, mean and minimum temperatures, 01 January 2024–30 June 2025', 2025a, <https://www.pagasa.dost.gov.ph/climate/climate-data>, accessed 26 November 2025

—, ‘Special Weather Outlook for 2025 National and Local Elections (12 May 2025)’, 9 May 2025b, <https://www.pagasa.dost.gov.ph/article/178>, accessed 6 November 2025

—, ‘Climate change in the Philippines’ [n.d.a], <https://www.pagasa.dost.gov.ph/information/climate-change-in-the-philippines>, accessed 12 November 2025

—, ‘Climate of the Philippines’, [n.d.b], <https://www.pagasa.dost.gov.ph/information/climate-philippines#:~:text=The%20combination%20of%20warm%20temperature,location%20of%20the%20mountain%20systems>, accessed 6 November 2025

Philippine Red Cross, ‘Ph Red Cross alerts the public against heat-related emergencies amid rising heat indices’, 5 March 2025a, <https://redcross.org.ph/2025/03/05/ph-red-cross-alerts-the-public-against-heat-related-emergencies-amid-rising-heat-indices/>, accessed 10 August 2025

—, ‘Going the Extra mile: Gordon salutes PRC staff, volunteers after successful 2025 election operations’, 10 June 2025b, <https://redcross.org.ph/2025/page/2/>, accessed 6 November 2025

Philippines Statistics Authority (PSA), ‘Highlights of the population density of the Philippines 2020 census of population and housing’, 23 July 2021, <https://psa.gov.ph/content/highlights-population-density-philippines-2020-census-population-and-housing-2020-cph>, accessed 12 November 2025

Philippines, Republic of, ‘1987 Constitution of the Republic of the Philippines’, 1987, <https://lawphil.net/consti/cons1987.html>, accessed 6 November 2025

—, ‘Republic Act No. 7904, 23 February 1995’, 1995, <https://elibrary.judiciary.gov.ph/thebookshelf/showdocs/2/2954>, accessed 6 November 2025

—, ‘Republic Act No. 8189: The Voter’s Registration Act of 1996 [Election law]’, 1996, <https://comelec.gov.ph/?r=VoterRegistration/RelatedLaws/RA8189>, accessed 8 November 2025

—, ‘Republic Act No. 9369: An Act Amending RA 8436, Philippine Senate / House of Representatives, Manila’, 2007, <https://comeleclaw.tripod.com/ra9369.pdf>, accessed 26 November 2025

—, ‘Republic Act No. 10121’, 2010, <https://lawphil.net/statutes/repacts/ra2010/ra_10121_2010.html>, accessed 25 December 2025

RTVM (official Presidential Broadcast Staff – Radio Television Malacañang), ‘Ceremonial Energization of the Mindanao-Visayas Interconnection Project’, 26 January 2024, <https://rtvm.gov.ph/ceremonial-energization-of-the-mindanao-visayas-interconnection-project/>, accessed 17 August 2025

Sampang, D., ‘Comelec to train over 186,000 teachers for 2025 polls’, Inquirer.net, 31 January 2025a, <https://www.inquirer.net/427048/fwd-comelec-to-train-over-186000-eb-members-for-2025-polls/>, accessed 8 November 2025

—, ‘Comelec completes printing of official ballots for 2025 polls’, Inquirer.net, 15 March 2025b, <https://www.inquirer.net/432723/printing-of-ballots-for-2025-polls-now-100-done-comelec/>, accessed 8 November 2025

Santos, J., ‘Voters warned of heat-related illnesses as Filipinos cast ballots’, Manila Bulletin, 12 May 2025, <https://mb.com.ph/2025/05/12/voters-warned-of-heat-related-illnesses-as-filipinos-cast-ballots>, accessed 6 November 2025

Sicat, A., ‘You can now register anywhere: Your guide to Comelec’s nationwide voter registration’, Philippine Information Agency, 23 January 2024, <https://pia.gov.ph/regions/you-can-now-register-anywhere-your-guide-to-comelecs-nationwide-voter-registration/>, accessed 6 November 2025

Tachev, V., ‘The 2025 Heatwave in Southeast Asia: a window into the future’, Climate Impacts Tracker Asia, 2025, <https://www.climateimpactstracker.com/2025-heatwave-in-southeast-asia/#:~:text=2025%20brought%20extreme%20heat%20to,the%20entire%2090%2Dday%20period>, accessed 25 December 2025

Tan, I. R. R., ‘Pagasa warns vs. extreme heat, advises on best time to vote’, Sunstar, 6 May 2022, <https://www.sunstar.com.ph/cebu/local-news/pagasa-warns-vs-extreme-heat-advises-on-best-time-to-vote?utm_source=chatgpt.com>, accessed 13 November 2025

UNDRR, ‘No such thing as a natural disaster’, United Nations Office for Disaster Risk Reduction, viewed 26 November 2025, <https://www.undrr.org/our-impact/campaigns/no-natural-disasters>, accessed 13 November 2025

World Meteorological Organization, ‘Extreme heat impacts millions of people’, 7 August 2025, <https://wmo.int/media/news/extreme-heat-impacts-millions-of-people>, accessed 13 August 2025

World Population Review, ‘Southeast Asia Population 2025’, 14 October 2025, <https://worldpopulationreview.com/continents/southeast-asia>, accessed 8 November 2025

Annex A. Interview guide—Case study on heatwave and the 2025 Philippine elections

Project context: This guide contains the questions that will be asked during the interview for the case study on Natural Hazards and Elections in the Philippines, commissioned by International IDEA and conducted by the Democratic Insights Group (DIG). The questions are tailored to your role and jurisdiction.

For Provincial Election Supervisor of Bulacan

- Can you describe how the heatwave conditions between December 2024 and May 2025 affected election preparations in Bulacan?

- What measures did your office take to mitigate risks of extreme heat to voters, polling staff and election infrastructure?

- Did your office coordinate with PAGASA, LGUs, or disaster agencies on heat advisories and their impact on election planning?

- How did extreme heat affect voter turnout and voter experience in Bulacan?

- Were election staff (BEIs, teachers, volunteers) given guidance or protection against heat stress?

- How did the heatwave affect transport, storage, and functioning of election materials (e.g. ballots, VCMs)?

- Looking back, what lessons can your office draw from administering elections under extreme heat?

- What permanent or long-term measures should be institutionalized for future elections under climate stress?

- Bulacan experienced both extreme heat and dense precinct populations. How did your office manage crowding and voter flow under these conditions?

For Provincial Election Supervisor of Pangasinan

- Can you describe how the heatwave conditions between December 2024 and May 2025 affected election preparations in Pangasinan?

- What measures did your office take to mitigate risks of extreme heat to voters, polling staff and election infrastructure?

- Did your office coordinate with PAGASA, LGUs, or disaster agencies on heat advisories and their impact on election planning?

- How did extreme heat affect voter turnout and voter experience in Pangasinan?

- Were election staff (BEIs, teachers, volunteers) given guidance or protection against heat stress?

- How did the heatwave affect transport, storage, and functioning of election materials (e.g. ballots, VCMs)?

- Looking back, what lessons can your office draw from administering elections under extreme heat?

- What permanent or long-term measures should be institutionalized for future elections under climate stress?

- Pangasinan recorded some of the highest heat indices nationwide. How did this localized intensity shape your preparations compared to previous elections?

For Regional Election Director of the National Capital Region

- Can you describe how the heatwave conditions between December 2024 and May 2025 affected election preparations in NCR?

- What measures did your office take to mitigate risks of extreme heat to voters, polling staff and election infrastructure?

- Did your office coordinate with PAGASA, LGUs or disaster agencies on heat advisories and their impact on election planning?

- How did extreme heat affect voter turnout and voter experience in NCR?

- Were election staff (BEIs, teachers, volunteers) given guidance or protection against heat stress?

- How did the heatwave affect transport, storage and functioning of election materials (e.g. ballots, VCMs)?

- Looking back, what lessons can your office draw from administering elections under extreme heat?

- What permanent or long-term measures should be institutionalized for future elections under climate stress?

- As Regional Director, how did you ensure consistency of guidance across multiple highly urbanized cities in NCR during the heatwave?

- Did the urban environment (e.g. heat island effect, limited shaded polling places) present unique challenges in NCR? How did you address them?

ANNEX B. Data Source Archiving

The datasets downloaded from the COMELEC Statistics page have been archived in the research team’s shared drive to ensure traceability of the materials used.

About the authors

Telibert Laoc is a co-founding trustee of the Democratic Insights Group, a think tank promoting electoral competitiveness and voter-centred processes. He is a senior professional lecturer at De La Salle University, Manila, and formerly served as senior resident director for elections and civil society development in Asia at the National Democratic Institute (NDI). Since joining NDI in 2004, he has directed election programmes across Afghanistan, Bangladesh, Bougainville, Indonesia, Papua New Guinea and Timor Leste. A former National Vice Chairperson of NAMFREL, he continues to work on electoral integrity, technology in elections and democratic reform. He holds an MBA from the Asian Institute of Management and is a fellow of the Institute of Corporate Directors.

Lourisze Cayle Juliana C. Deseo holds a Bachelor of Arts in Political Science from De La Salle University, where she graduated magna cum laude. She is currently working with the Democratic Insights Group. Her work focuses on Philippine politics and elections, with a particular interest in how psychological factors influence political attitudes and behaviour.

Yaelim Jeung works with the Democratic Insights Group and graduated magna cum laude with a Bachelor of Arts in Political Science from De La Salle University, where she held leadership roles in the Political Science Society and student government. Her work focuses on political participation, governance and behavioural sciences, and she has been involved in community initiatives such as the Esperanza Project, supporting advocacy and public engagement efforts.

Contributors

Erik Asplund, Senior Advisor, Electoral Processes Programme, International IDEA.

Sarah Birch, Professor of Political Science and Director of Research (Department of Political Economy), King’s College London.

Ferran Martinez i Coma, PhD, Professor, School of Government and International Relations at Griffith University, Queensland.

© 2026 International Institute for Democracy and Electoral Assistance

International IDEA publications are independent of specific national or political interests. Views expressed in this publication do not necessarily represent the views of International IDEA, its Board or its Council members.

With the exception of any third-party images and photos, the electronic version of this publication is available under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 (CC BY-NC-SA 4.0) licence. You are free to copy, distribute and transmit the publication as well as to remix and adapt it, provided it is only for non-commercial purposes, that you appropriately attribute the publication, and that you distribute it under an identical licence. For more information visit the Creative Commons website: <http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/4.0>.

This case study is part of a project on natural hazards and elections, edited by Erik Asplund (International IDEA), Sarah Birch (King's College London) and Ferran Martinez i Coma (Griffith University).

Design and layout: International IDEA

DOI: <https://doi.org/10.31752/56818>

ISBN: 978-91-8137-083-6 (PDF)

ISBN: 978-91-8137-084-3 (HTML)