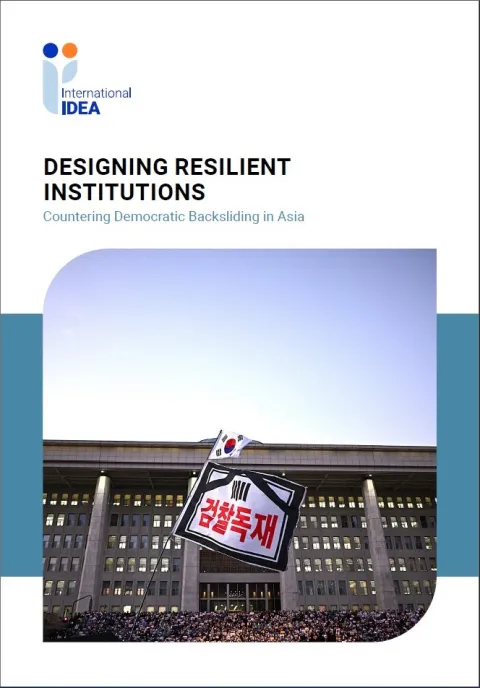

Designing Resilient Institutions

Countering Democratic Backsliding in Asia

Government-led democratic backsliding has entailed attacks on key democratic institutions in countries worldwide. Asia is no exception. This report identifies the particular democratic challenges facing countries in Asia and identifies potential measures for enhancing institutional resilience to withstand democratic backsliding and governmental attacks.

In 2023 International IDEA published Designing Resistance: Democratic Institutions and the Threat of Backsliding, which mapped the measures commonly employed by democratic backsliders and offered recommendations for building institutions that are more resistant to backsliding (Bisarya and Rogers 2023).

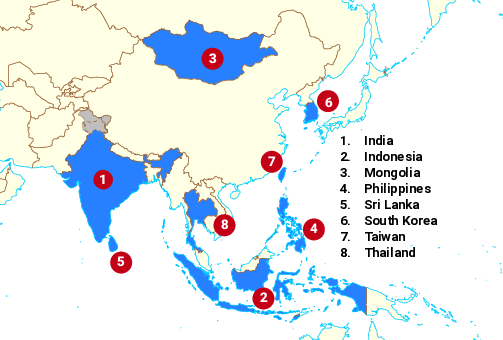

This current report, Designing Resilient Institutions: Countering Democratic Backsliding in Asia, applies the global analytical framework developed by International IDEA in 2023 to Asia. Case studies of eight countries across this diverse region—India, Indonesia, Mongolia, the Philippines, South Korea, Sri Lanka, Taiwan and Thailand—capture key particularities of the democratic challenges facing countries in Asia and identify potential measures for enhancing institutional resilience to counter governmental attacks.

Focusing on the experiences of the case-study countries in Asia reveals the five most common measures employed to weaken or diminish core institutions of democracy: (a) draining, packing and instrumentalizing the judiciary; (b) tilting the electoral playing field; (c) weakening the power of the existing opposition; (d) expanding executive power; and (e) shrinking the civic space.

While there is some overlap with global experiences, there are significant divergences in the measures used to undermine democratic institutions in Asia compared with global trends. These measures include impeaching judges, interfering with the courts through unusually expansive chief justice powers, banning political parties, co-opting the opposition in coalitional presidential systems, subverting parliamentary processes through abuse of the speaker’s role and the ‘money bill’ procedure, distorting presidential systems through the development of ‘legislative aggrandizement’, undermining institutional divisions and subverting the separation of powers through family ties and dynastic politics, militarizing governance, abusing colonial-era sedition laws, shutting down the Internet and criminalizing the spread of so-called ‘fake news’.

Addressing democratic backsliding is not easy. Experiences in Asia demonstrate five central challenges to navigate when designing institutions and reforms to resist backsliding:

- Resilience conundrum. The catch-22 whereby the very institutions charged with carrying out reforms are often themselves driving or facilitating backsliding.

- Visibility. Backsliding tactics are often sophisticated and difficult to identify and resist.

- Mutability. Backsliding governments are persistent. If one option is not open, other routes will be found to achieve the same aim. In this sense, backsliding is like a virus mutating over time.

- Priorities. Backsliding encompasses a wide range of measures, making it challenging to identify possible channels for resistance and to determine which resistance strategies to prioritize.

- Risk of abuse. All measures aimed at enhancing resilience to backsliding are themselves open to abuse by anti-democratic governments and institutional actors. However, careful attention to the initiation and employment of resilience-enhancing measures can mitigate the risk.

With this in mind, this report provides a set of six reflections for how to approach designing and strengthening institutions that are resilient enough to resist governmental attacks. The ‘six Bs of resilience’ entail the following:

- Blocking bad laws by identifying key channels for both preventing anti-democratic legislation and countering abuse of existing legislation;

- Broadening state offices to diffuse power among different actors to frustrate capture by government while maintaining adequate functioning;

- Blindfolding backsliders by introducing an element of unpredictability into institutional operations and the selection of office holders;

- Balancing imbalances by addressing excessive concentrations of political power, mitigating inter- and intra-institutional imbalances; and recognizing the dangers of simultaneous elections;

- Recognizing the Bureaucracy as a core institution that can both counter democratic backsliding and undermine democracy; and

- Building holistically so that the components of each constitutional system work together.

The report concludes by identifying areas for future research and policy work in Asia and, potentially, beyond. The analysis in this report will assist and inform public bodies engaged in reviewing legal and constitutional frameworks, civil society organizations seeking to strengthen their democracy and the international democracy assistance community engaged in supporting democracy worldwide.

Democratic backsliding—where a democratically elected government undermines the democratic system through legal means—has spread and intensified globally since the mid-2000s. International IDEA has pursued a solutions-oriented approach to this challenge. In particular, a landmark report published in 2023, Designing Resistance: Democratic Institutions and the Threat of Backsliding, sets out a systematic account of the diverse measures employed by democratically elected governments to undermine or distort democratic functioning and contemplates how to build institutions that are more resistant to backsliding (Bisarya and Rogers 2023).

Given that the 2023 report provides a global assessment, its framework can be applied to specific world regions for more granular analysis. This report focuses on Asia, which features diverse dynamics in terms of democratic development and direction. By examining eight countries across the region—India, Indonesia, Mongolia, the Philippines, South Korea, Sri Lanka, Taiwan and Thailand—this report aims to capture key democratic challenges facing them, which both align with, and depart from, global trends, and to identify potential measures for enhancing institutional resilience against governmental attacks.

By providing clear, evidence-based and practical analysis, the purpose of this report is to assist public bodies engaged in reviewing legal and constitutional frameworks, civil society organizations seeking to strengthen their democracy and the international democracy assistance community engaged in supporting democracy worldwide.

This report focuses on institutional resilience to governmental measures that undermine democratic functioning. As discussed in Chapter 6, however, a full understanding of democratic backsliding requires a more comprehensive perspective. An institutional analysis alone is insufficient without taking into account the broader contextual, behavioural, structural and cultural issues that have an impact on the democratic context. Although these issues are outside the scope of this report, they warrant further research. Such issues include internal institutional cultures and individual office-holders’ views of their constitutional responsibilities in relation to the guardianship of democratic norms, the gender and minority dimensions of backsliding processes, changing political behaviour and the role of political parties, the rapidly evolving media and information landscape, citizen trust in public institutions and attitudes towards democracy, and societal support for strongman governance and ‘authoritarian nostalgia’.

Polities in Asia have a long history of democratic and deliberative practice. Processes of decolonization and democratic transitions from the 1940s onwards have slowly increased the number of democracies in the region. A leading study (Croissant, Hengge and Wintergerst 2024: 2) charts this growth from 3 democracies in 1980 to 11 by 2017, including two of the world’s largest democratic countries—India and Indonesia.

However, this trend has not been uniform across the entire region. Many countries remain under military dictatorships or one-party rule; democracy continues to face competition from these alternative political models, and democratic backsliding has now become a dominant trend.

International IDEA’s The Global State of Democracy 2023 report addresses the state of democracy globally according to four categories of democratic performance: (a) Representation; (b) Rights; (c) Rule of Law; and (d) Participation. Key insights from Chapter 5 of the report, on Asia and the Pacific, include the observation that, while the broad democratic decline experienced in the region in recent years has slowed or even halted, a continued downward trend is seen regarding key Civil Liberties, such as Freedom of Expression and Freedom of Association and Assembly. In addition, the region’s aggregate Freedom of the Press score, which peaked in 2012, has now reverted to 2001 levels, with significant declines observed in a range of countries, including the Philippines, South Korea, Sri Lanka and Taiwan. Resonating with a now-expansive academic and policy literature, the trends in Asia align with trends worldwide. In all world regions, deterioration is the dominant pattern, continuing a growing trend observed in International IDEA’s Global State of Democracy Indices over the past six years (International IDEA 2023).

Most countries in the region remain below the global average in every category, bar Participation, although positive developments include significant improvements in Rule of Law (Maldives, Taiwan and Uzbekistan) and Representation (Malaysia, Maldives and Thailand). Across the region, the courts, anti-corruption bodies and at times mass street protests have been the main bulwarks against the undermining of democratic structures and processes due to ineffective legislatures and crackdowns on organized civil society (International IDEA 2023).

The updated Global State of Democracy data for 2024 suggests intensifying democratic threats in the case-study countries selected for this report (International IDEA 2024). India and Indonesia are counted—alongside countries such as pre-coup Myanmar and Kyrgyzstan—as ‘mid-performing countries experiencing net declines on a significant number of indicators’ (International IDEA 2024: 12). In the five-year period covered by this data, India has suffered ‘statistically significant’ declines in Credible Elections, Free Political Parties, Access to Justice, Civil Liberties, Judicial Independence and Civic Engagement; Indonesia has suffered declines in Credible Elections, Effective Parliament, Freedom of Expression, Access to Justice and Judicial Independence; South Korea’s performance on Effective Parliament, Access to Justice, Freedom of the Press and Civil Liberties has declined; and Mongolia has witnessed declines in Civil Liberties and Free Political Parties (International IDEA 2024: 12–14). Many declines in rights protection affect the freedom of expression, including declines in protection of press freedom in Taiwan (International IDEA 2024: 18). On the positive side, the data suggests that Thailand continues to see improvements, including in the areas of Effective Parliament and Credible Elections. However, its democratic performance remains lower than before the 2014 coup d’état (International IDEA 2024: 8–9).

Four additional contextual factors directly relate to institutional dimensions of backsliding and resistance thereto. First, compared with regions such as Europe or South America, there is a wider diversity of political systems and less political cross-influence among countries in Asia. Second, the geopolitical context is evidently shaped by the rise of China as an authoritarian superpower, the growing geopolitical importance of India as a democracy undergoing profound change and Russia’s interventionist foreign policy. Third, the issue of conflict looms large and generates risk factors for democratic backsliding in the affected countries. A number of countries face governance challenges rooted in a recent past of internal conflict (e.g. the Philippines, Sri Lanka), ongoing internal conflict (e.g. the case of Kashmir) or the threat of serious conflict (e.g. South Korea, Taiwan). Finally, economic factors are also important, including the experience of grave economic crises (e.g. Sri Lanka), the outsized power of economic elites (e.g. Indonesia, the Philippines), and the asymmetry of economic relations between China and other countries across the region through the Belt and Road Initiative, which has put some countries in a debt trap and placed democratically elected governments under serious pressure. For less developed countries in the region, the long-standing (albeit problematic) idea of development as ‘getting to Denmark’, which views economic progress as predicated upon democratization, now competes with the idea of ‘getting to Singapore’ or ‘getting to China’, where democratic progress and economic progress are decoupled (Daly and Samararatne 2024: 21).

While the 2023 Designing Resistance report presents a global overview of backsliding patterns, this report focuses on a more targeted cohort of countries as examples of both democratic threats and institutional resistance to threats across Asia. The case studies of the selected countries broadly capture the diversity of the region, representing varying political systems, country size and territorial organization, state structure, governance models and geographic location. As indicated in Chapters 3 and 4, all eight countries have experienced different trajectories in their democratic development, ranging from democratic deficiencies to outright rupture in democratic governance.

Table 2.1 presents a simple overview of the eight case-study countries. The dates provided for transitions to democracy are indicative and relate to either (a) a transition to democratic governance after independence from colonial rule, marked as (I); or (b) a transition to democratic governance after authoritarian rule, marked as (A). The aim is simply to provide a more nuanced picture than would be indicated by the date of the constitution’s adoption.

| Country | Year constitution was adopted | Transition to democracy | Governance system | Population |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| India | 1949 | 1947 (I) | Parliamentary | 1.45 billion |

| Indonesia | 1945 | 1998 (A) | Presidential | 283 million |

| Mongolia | 1992 | 1990 (A) | Semi-presidential | 3.5 million |

| Philippines | 1987 | 1986 (A) | Presidential | 116 million |

| South Korea | 1948 | 1986 (A) | Presidential | 52 million |

| Sri Lanka | 1978 | 1948 (I) | Presidential | 23 million |

| Taiwan | 1947 | 1992 (A) | Presidential | 23 million |

| Thailand | 2017 | 2023 (A) | Parliamentary | 72 million |

While the selected countries exhibit some commonalities (e.g. every country, with the exception of Thailand, is a republic), there are stark disparities in population, from over 1 billion (India) to under 4 million (Mongolia). Indonesia’s population of 283 million makes it the third-most-populous democracy in the world, while India’s size means that one in every three people living in a democracy worldwide is Indian (Chowdhury and Keane 2021). Population density is also highly diverse. Whereas Mongolia has the second-lowest population density in the world, countries such as India, the Philippines and South Korea have a very high population density by global standards. The strong trend of urbanization across the case-study countries and the presence of megacities such as Bangkok, Jakarta, Manila, New Delhi and Seoul are also important factors in understanding the texture of the political order in these countries.

Spatially, the eight countries range from massive contiguous territories (India) to archipelagic entities (Indonesia, the Philippines) and island states (Sri Lanka, Taiwan). However, India is the sole federal state in the cohort, although two countries accord greater autonomy to specific regions—Aceh and Papua in Indonesia (Barter and Wangge 2022), and the Bangsamoro region in the Philippines (Masuhud Alamia 2023). The issue of federalism is also a live and contentious debate in Sri Lanka, rooted in long-standing interethnic contestation and conflict between the Sinhala-Buddhist majority and the Tamil minority (Welikala 2017). More autocratic government generally tends to strengthen centralization, as seen in the recentralization of Thailand, diminishing prior decentralization efforts, after the 2014 coup (Harding and Leelapatana 2020) or the focus on national integrity and one-nationism in India under successive Modi administrations (Tillin 2024).

Each of the case studies reveals different dimensions of democratic backsliding and threats, with some countries experiencing systemic transformation, others merely experiencing concerning developments, and a minority departing entirely from the backsliding paradigm, such as Thailand’s alternating cycles of civilian and military government. This diversity counsels caution in offering any universal prescriptions for enhancing institutional resilience to counter democratic threats. However, where a vulnerability in one national system has been identified, it often has relevance for other countries. The differences in democratic starting point, trajectory and constitutional context of these case studies are explored in greater detail in the Chapter 3.

This report adopts the main definitions set out in the 2023 Designing Resistance report. However, the regional context requires a careful and nuanced approach to terminology.

3.1. Democracy

In line with the 2023 Designing Resistance report, this report employs Dixon and Landau’s (2016: 277) concept of a ‘minimum core of a democratic constitution’, which encompasses the core institutions, procedures and democratic rights essential to maintaining a system of ‘multiparty competitive democracy’. These include elections, core civil and political rights, the judiciary, effective parliament, public administration and oversight institutions. It may be noted that this is a narrower definition of democracy than that used by International IDEA across its wider democracy analysis and support work, which recognizes popular control and political equality as the two core principles of democracy, encompassing ‘popular control over public decision making and decision makers, and equality of respect and voice between citizens in the exercise of that control’ (Skaaning and Hudson 2024: 7). The concept of a minimum core of a democratic constitution aims to provide a better framework for analysing democratic-backsliding processes as opposed to governmental policies that may affect rights or welfare provisions, for example, but which do not threaten the functioning or viability of the democratic system itself.

What is considered essential to a democratic system will differ from country to country. That the Indian Supreme Court deems federalism to be part of the ‘basic structure’ of India’s Constitution (Singh and Singhal 2024) raises the question of whether it would be considered part of the democratic minimum core in that country. Similarly, the judicial power to strike down legislation incompatible with the a country’s constitution is common among the countries considered in the case studies, with the exception of Indonesia, where the Constitutional Court alone can perform abstract review (Hendrianto 2016), and Sri Lanka, where judicial review is limited to a pre-enactment review of bills and a review of executive and administrative action (Samararatne 2022). In the electoral arena, various constitutional systems integrate state frameworks and customary practices. In Indonesia, for instance, the traditional communities in Bali and Papua practise communal voting without a secret ballot (Faiz et al. 2023).

3.2. Democratic backsliding

Democratic backsliding means the ‘state-led debilitation or elimination of any of the political institutions that sustain an existing democracy’ (Bermeo 2016: 5). As used in this report, the process of democratic backsliding consists of three elements:

- It is carried out by a government which comes to power through competitive elections.

- It is achieved through legal means.

- It alters the core of constitutional democracy to create an unfair electoral playing field or weaken constraints on the power of the executive.

Two points are important here. First, a variety of other terms capture the dynamics of democratic regression, such as ‘autocratization’ (Lührmann and Lindberg 2019; Truong, Ong and Shum 2024) as well as a wide range of others, including ‘democratic deconsolidation’, ‘abusive constitutionalism’ and ‘autocratic legalism’ (Daly 2019). This report follows the 2023 Designing Resistance report in employing the term ‘democratic backsliding’ while taking a nuanced approach that recognizes the particularities of the Asian context (see 3.3: Democratic backsliding within the Asian context). Second, as indicated in the Introduction, the definition of backsliding used in this report is clearly a partial definition focused on the functioning, operation and interaction of institutions. Recognizing that one report cannot address all societal trends undermining democracy, Chapter 6 sets out a research agenda for broader analysis. In particular, an institutionalist analysis does not overlook the importance of broader human rights considerations, including the racial, ethnic or religious dimensions of exclusionary practices or the gendered nature of strongman rule.

The remainder of this chapter addresses four dimensions of this overarching conceptual framework to better capture the challenges facing Asia as a whole and the eight case-study countries covered in this report in particular: (a) backsliding; (b) backsliders; (c) legal means; and (d) resistance and resilience.

3.3. Democratic backsliding within the Asian Context

The notion of ‘democratic backsliding’ suggests a certain level of democratic development as a starting point, which is then rolled back by an errant government. The countries covered by the case studies in this report present a greater level of complexity than countries in other regions, such as Brazil, Poland and the United States, insofar as they encompass not only long-established democracies (e.g. India) and younger democracies but also countries suffering cyclical swings between more autocratic and more democratic rule (e.g. Sri Lanka, Thailand). Any analysis must consider the complexity of democratic development, where positive and negative trends often take place at the same time rather than in a simple linear fashion.

Most countries analysed in this report belong to the so-called third wave of democratization, having experienced a democratic transition from authoritarianism in the 1980s (e.g. the Philippines, South Korea, Taiwan) or the 1990s (e.g. Indonesia, Mongolia). In some cases, a ‘third wave’ country has achieved consolidated democracy (South Korea, Taiwan). In others, however, the initial momentum did not lead to full democratic consolidation (Indonesia, the Philippines), and democratic progress has given way to backsliding or a crisis of democratic institutions. In some countries, the democratic trajectory is contested: concerning Mongolia, for instance, Sumaadii and Wu (2022) have suggested that perceived patterns of backsliding are better understood as stagnation and the stalling of democratic gains rather than democratic reversal. As seen in Indonesia, however, stagnation can tip into fuller regression (Warburton and Power 2020). Discerning the overall systemic trajectory essentially requires a mix of evidence and interpretation.

Other countries fit even less neatly into the backsliding paradigm. Sri Lanka has witnessed cyclical improvements and deterioration in the quality of its democratic system and institutions, including extensive state capture during the Rajapaksa governments, a limited window for democracy building in 2015 and a rolling constitutional crisis since 2022 (Ganeshathasan 2024).

Contestation concerning the extent of presidential power in Sri Lanka has generated ‘intra-constitutional cycling’, with successive constitutional amendments adopted as two political blocs with competing visions of the political order gain the upper hand, resulting in a tug of war between an empowered executive presidency and a semi-presidential structure that balances power between the president and parliament (Daly and Samararatne 2024: 24).

Similarly, while Thailand has faced successive coups (most recently in 2014) and the phenomenon of ‘constitutional cycling’, where its constitution is replaced over and over again (most recently in 2017), each coup has failed to reset democratic society entirely. Rather, strains of democratic functioning and development have persisted and transcended military interventions, with the result that Thailand is best understood as a ‘weak’ or ‘interrupted’ democracy rather than a young post-authoritarian democracy (Chambers and Waitoolkiat 2020).

This context highlights quite a different challenge for most countries considered here, compared with the overall thrust of the 2023 Designing Resistance report, which places significant emphasis on ‘strengthening’ democracy and on ‘[fixing] the roof while the sun is shining’ (Bisarya and Rogers 2023: 17) by considering processes to increase the resistance of constitutions to potential backsliding. While countries such as Mongolia, South Korea and Taiwan might still fit within that paradigm (although this is now sharply contested), for the remainder of the case-study cohort in this report the task is to contemplate how institutional resilience can be enhanced in a context of significant, or even severe, backsliding.

Whereas reviews of constitutional resilience in countries such as the Netherlands and Sweden (Bisarya and Rogers 2023: 88) have contemplated hypothetical threats in a context of merely nascent or potential democratic regression, ongoing backsliding in many of the countries analysed here more fully reveals a suite of systemic vulnerabilities, offering a detailed data set for considering means of improving resilience. One approach for backsliding countries is to consider what fixes might be needed after a backsliding government has been removed from power (Daly 2023). However, this report takes the view that, even in contexts of active backsliding, a focus on institutional resilience can help not only to identify ways to push back or slow down backsliding but also to develop preparedness for a potential future moment when an anti-democratic government is ousted in elections and a broader suite of preventive measures can be put in place.

3.4. Backsliders

This report follows the 2023 Designing Resistance report by generally avoiding the term ‘authoritarians’ in favour of ‘democratic backsliders’, as, beyond their use of the law as a preferred tool of oppression, the governments considered in this report not only usually claim genuine popular support but also often actually maintain majority popular support. In light of this distinction, however, two clarifications are necessary.

First, it is evident that Thailand’s Government is a clear outlier insofar as it is a civilian government installed in 2021 after a coup d’état in 2014, in a system where the electoral field has been extensively distorted and is managed by key institutional actors, including the military, the judiciary, the monarchy and associated elites, through party dissolutions and free-speech restrictions, including lèse-majesté laws, as well as a new constitutional framework (see 4.2.1: Changing the constitutional framework). Second, as discussed below, cases abound of ‘abusive judicial review’ (Dixon and Landau 2021: Chapter 5), whereby courts act as ‘government enablers’ (Sadurski 2019). In many cases, courts act in this way due to executive interference, which converts them into a key mechanism for the government’s undermining of democracy. This mechanism can be seen, for instance, in the Indonesian Constitutional Court’s highly controversial decision in October 2023 that cleared the way for President Joko Widodo’s1 son to run as a vice-presidential candidate in the 2024 election despite being younger than the constitutionally required age for candidates (Putri and Khasyi’in 2023).

However, judicial actors may also enable backsliding without being completely captured by the government. They might operate independently but remain aligned with the establishment ideology: Thailand’s Constitutional Court, for instance, continues to distort democratic politics. This was vividly demonstrated by its recent dissolution of the largest opposition party, the Move Forward Party, based on the claim that the party’s calls for reform of lèse-majesté laws violated the Constitution (Saksornchai 2024).

3.5. Legal means

This report focuses on the legal means by which democratic functioning and institutions are degraded across the case-study countries. As International IDEA’s 2023 report suggests, such means can include constitutional amendments, the adoption of legislation or even changes to sub-legislative procedures.

Constitutional replacement has been a central feature of democratic backsliding in key countries that have informed the backsliding paradigm—especially Hungary and Venezuela. Where constitutional replacement or amendment is available to a backslider government, it can facilitate a structural transformation of the democratic system in a manner that more fully hollows it out, although countries such as Poland demonstrate that similarly extensive backsliding can also be achieved without any formal constitutional amendment. However, it is important to emphasize that constitutional replacement is not a dominant feature of democratic backsliding worldwide, including in the Asian countries analysed in this report. Across the case-study cohort for this report, constitutional replacement as a backsliding tactic is found only in Thailand, where it is unusually common by global and regional standards, with five texts adopted since 2000 (see 4.2.1: Changing the constitutional framework). Constitutional amendment is also uncommon. Sri Lanka is an outlier, having amended its 1978 Constitution 20 times, seriously undermining fundamental liberties and checks and balances (Daly and Samararatne 2024: 24).

Elsewhere, a constitutional amendment that would affect the minimum democratic core has been mooted but rarely achieved. In Indonesia, despite increasing calls for restoration of the 1945 Constitution to its original authoritarian-era text by reversing the liberal-democratic amendments introduced during the reformasi era of 1998–2002, this has not yet been achieved (Satrio 2023; Nugraha 2023). No amendments have been made to the constitutions of the Philippines, South Korea or Taiwan (Liao, Chien and Chang 2009; Constitute n.d.); in the Philippines, however, concerns are growing about possible amendments to undermine the democratic system (Tamase 2024). Successive constitutional amendments in Mongolia have raised concerns, but it can be hard to differentiate between churn and backsliding (Odonkhuu 2023). In India, the Supreme Court’s striking down of an amendment to replace the collegium system by which judges play a dominant role in judicial appointments (Ananda 2023; Jaising 2024) is better understood as rooted in institutional self-protection rather than resistance to executive aggrandizement, given that the Court has generally been supine in the face of backsliding under the Modi government (Sen 2024: 72). Abuse of constitutional mechanisms is common, including abuse of judicial impeachment in both the Philippines and Sri Lanka, and of the power to dissolve political parties in Thailand.

Given the obstacles to constitutional replacement and amendment discussed above, legislation appears to be the dominant legal avenue for undermining democratic functioning across the case-study countries. This relates to both process (the functioning of the legislative process) and product (the substantive legislation produced). As discussed below, the integrity of the law-making process has been deeply degraded, especially by constraining the capacity of the opposition to play their role in deliberating on draft legislation. Examples of highly concerning legislation discussed below include the criminalization of fake news in Indonesia, the Aadhar Act in India and the Official Powers Law in Taiwan. One also finds the employment of colonial-era defamation and sedition laws to silence critics in countries such as India, where the Modi government has vastly increased the use of such laws (Hari 2022).

As discussed below, practices beyond the adoption of legislation are also important—for example, the South Korean Government excluded critical outlets from international press tours. In other cases, threats to democracy arise in entirely legal ways, such as the further integration of the Indonesian military into civilian institutions and life, enabled by presidential decree (Setijadi 2021: 308).

3.6. Resistance and resilience

The concepts of resistance and resilience are central to this report. As observed in the 2023 Designing Resistance report, there is no possibility of rendering any constitutional democracy fully ‘backsliding-proof’, in the same way that buildings cannot be 100 per cent earthquake-proof. However, just as buildings can be made more earthquake-resistant through careful design and the minimization of structural vulnerabilities, carefully considered and calibrated institutional design can strengthen the resilience of democracy. The 2023 report suggests that certain forms and facets of institutional design may act as enabling or disabling factors for issues beyond the nuts and bolts of governance structures.

This report follows this approach by drawing a distinction between structural resistance, which concerns institutional design in the abstract, and applied resistance, which concerns the actuality of resistance by institutions in different case-study countries, where pushback does not always come from the institutions most clearly charged with constitutional guardianship, or where it may mutate over time as different institutions are disabled. In Sri Lanka, for instance, the guarantor branch, comprising institutions such as the Constitutional Council and Election Commission—perhaps due to the diminished capacity of the judiciary—is central to resisting backsliding measures (Samararatne 2023). Judicial quiescence in India has placed greater pressure on the political party system and civil society to mount a defence of the Constitution (Jain 2024; Jaising 2024), raising questions about the capacity of highly court-centric systems to withstand attack.

The 2023 report also employs the term ‘resilience’, which is helpful in further delineating what resistance means for the purpose of this report. Arban (2023: 89) suggests that resilience in the South Asian context may be viewed as having three dimensions: (a) flexibility or adaptability; (b) a capacity to bounce back from difficult circumstances; and (c) a mechanism for coping with ‘taxing conditions’. A narrow approach would focus on the capacity to withstand specific crises, such as a pandemic (Durojave and Powell 2022). Certainly, ‘pandemic backsliding’ accelerated declines in key countries covered in the case studies in this report, including India, Indonesia, the Philippines and Sri Lanka, supporting research indicating that backsliding and hybrid regimes suffered deeper pandemic declines than so-called well-functioning democracies (International IDEA 2020; Daly 2022: 10). More broadly, bouncing back from a crisis and backsliding can be seen in developments such as the victory of Anura Kumara Dissanayake in Sri Lanka’s 2024 presidential elections, running on a campaign of transparency, anti-corruption and economic reform (Aamer 2024), or the strong showing by the opposition Indian National Developmental Inclusive Alliance (INDIA) in India’s 2024 elections. However, the former, rooted in mass popular mobilization through the Aragalaya protest movement, and the latter, relating to the actions taken by political parties, lie outside this report’s focus, which is limited to pushback by state institutions.

As a recent collection on constitutional resilience in South Asia suggests, resilience can also be understood in the negative sense as the persistence, or ‘stickiness’, of institutions and institutional practices that militate against the health, development and endurance of democracy (Jhaveri, Khaitan and Samararatne 2023). Examples of such stickiness include the military complex in Indonesia, the Philippines and Thailand; hyper-presidentialism in Sri Lanka; the legacy of repressive colonial-era legislation in India (e.g. sedition laws); or the excessive tutelary power of both the judiciary and the monarchy in Thailand. Many of these durable institutions and frameworks are hard-wired into the political system and difficult to change.

In this sense, defining resilience as a constitutional system’s capacity to ‘withstand attempts aimed at changing or violating its core elements’ (Jakab 2021) could be misleading without paying close attention to the constitutional framework itself. While it makes sense for countries with a fundamentally democratic constitution (e.g. India, Mongolia, South Korea) to contemplate resistance against threats to their democracy, they must also grapple with active sites of resistance against democratic functioning and proceed from a considered understanding of deep-seated governance pathologies, which may be reflected in the constitutional text or in entrenched and emerging practices and policymaking that undermine the constitutional system (Meyer 2021: 199). That is quite a different picture from exercises to contemplate enhancing resistance against backsliding in countries such as Sweden, where, despite deficiencies and growing threats, the constitutional order and all state institutions remain fundamentally democratic.

A final point is that while constitutional replacement or significant amendment might be desirable, it may not be possible in the short term. In such cases, the task is to think creatively about mitigating constitutional deficiencies through legislation and practice.

The starting point of this regional analysis is the 12 common methods employed by backsliders to undermine democratic institutions, elections, rights and freedoms set out in the 2023 Designing Resistance report (see Table 4.1). This chapter focuses on five of these general themes that represent the most common threads among the case studies selected for analysis. Examining these themes reveals both commonalities with global trends and particular characteristics of backsliding in the region. The following five themes are analysed: (a) draining, packing and instrumentalizing the judiciary; (b) tilting the electoral playing field; (c) weakening the power of the existing opposition; (d) expanding executive power; and (e) shrinking the civic space. Although specific examples are identified below, it is important to remain cognisant of the often mutually reinforcing effect of a diverse range of measures that, at first glance, may appear unconnected in a given country context.

| Draining, packing and instrumentalizing the judiciary | Examples include restricting a court’s jurisdiction or lowering the judicial retirement age to purge sitting judges from the bench. |

| Tilting the electoral playing field | Backsliders can tilt the electoral playing field by changing the electoral system to heavily favour the incumbent. |

| Weakening the opposition’s power | One way to weaken the opposition’s power is to amend parliamentary procedures to reduce the floor time or bargaining power of minority parties. |

| Creating a ‘democratic shell’ | A democratic shell can be created by incorporating measures into the constitution or legal system which are ostensibly democratizing or liberalizing but do not have that effect in practice. |

| Shifting competencies and creating parallel institutions | This method involves the transfer of powers from a non-captured institution to a captured one. |

| Capturing political institutions by realigning chains of command and accountability | One way to capture political institutions is to bring appointment procedures for key state actors under political control. |

| Engaging in selective prosecution and enforcement | An example is the prosecution of political opponents for low-level, non-political crimes. |

| Evading term limits | Presidents can evade their term limits by rotating power with a prime minister or removing the term limits altogether through reinterpretation of the constitution. |

| Expanding executive power | The most direct forms of the expansion of executive power include the arrogation of decree-making power or direct executive control over state finances. |

| Entrenching power through temporal tactics | Backsliders make major changes while enjoying a parliamentary supermajority and then make it as difficult as possible to undo those changes. |

| Shrinking civic space | Common ways to reduce the civic space include attacks on the media, civil society organizations and the civil liberties of the electorate. |

| Employing non-institutional strategies | Examples of non-institutional strategies include using populist rhetoric or supporting discriminatory policies. |

4.1. Draining, packing and instrumentalizing the judiciary

The 2023 Designing Resistance report sets out a range of measures used by anti-democratic governments to disable or capture an independent judiciary. Key measures identified in the report, such as altering appointment procedures and bodies, expanding courts, changing courts’ jurisdiction, creating new courts or altering retirement ages, are not prominent in this report’s case studies. Instead, the case studies illustrate alternative measures that are used to subordinate or distort the functioning of the courts or to raise concerns about institutional resilience in the face of backsliding. This chapter analyses judicial appointments, judicial impeachment, abuse of power by court presidents, unbalanced jurisdiction, and family and elite ties.

4.1.1. Judicial appointments

Key weaknesses in judicial appointments are found in Indonesia and India. In Indonesia, executive domination of the legislature under President Jokowi (see 4.3.1: Co-opting the opposition) has given the president disproportionate power over Constitutional Court appointments and the removal of judges, as seen in the replacement of the Court’s deputy chief justice in 2022 by order of the legislature and the president (Dressel 2024: 47). By contrast, while concerns have been raised in Mongolia regarding the 1992 Constitution’s allocation of virtually all power over judicial appointments to the president, this power does not appear to have been abused to date (Sumaadii and Wu 2022: 112). In India, the Supreme Court has famously arrogated ultimate power over appointments to senior Supreme Court justices, known as the collegium system. While this system may insulate judges, the fact that judicial tenures are short (with retirement at age 65) creates an opening for using post-judicial political appointments to undermine the independence of the judiciary: a recent example is the appointment of Chief Justice Palanisamy Sathasivam as governor of Kerala immediately after his tenure ended in 2014, with no ‘cooling off’ period (Shah 2022).

4.1.2. Judicial impeachment

Impeachment has been used in questionable ways in both Sri Lanka and the Philippines: by the strongman government of Mahinda Rajapaksa to remove the chief justice in Sri Lanka in 2013 (Tissa Fernando 2013) and unexpectedly in the Philippines in 2018 against Chief Justice Maria Lourdes Sereno, a vocal critic of another strongman, President Rodrigo Duterte (Steelman 2018; Dressel 2024: 45). In both cases, serious questions have arisen concerning not only political motivations to silence the judges but also certain deficiencies, including a failure to follow due process and a lack of clarity concerning the powers of key figures in the process (e.g. the president, the speaker of parliament).

4.1.3. Interference through the chief justice

Whereas abuse of judicial impeachment demonstrates how the leaders of apex courts have been targeted, two case studies further underscore the roles played by court presidents in backsliding contexts. Box 4.1 shows how interference via the chief justice in Indonesia arose due to family ties between the chief justice and the ruling party. In India, it would be difficult to fully capture the Supreme Court, given that it comprises 33 judges and sits in multiple bench formations, and never en banc. However, the chief justice has unusually broad powers to delay the hearing of cases and to assign cases to benches whose approach to a given constitutional controversy might be predictable (Sen 2024: 75).

Questions arose in 2018 when the Court’s four most senior judges after the Chief Justice—then Justice Dipak Misra, who had been appointed to the position by the Modi government in August 2017—unexpectedly left their courtrooms to hold the first press conference organized by Supreme Court judges since its establishment in 1949. In a long statement issued to the press, they declared that that the Court’s functioning was ‘not in order’ and that ‘unless [the Court] is preserved, democracy can’t be protected in [India]’ (Safi 2018). They also complained that the chief justice was selectively assigning important constitutional cases ‘having far-reaching consequences for the nation and the institution’ to his preferred benches without providing any justification (Banerjee 2018: 361). Potential limitations on the discretion of the chief justice are considered in Chapter 5.

4.1.4. Unbalanced jurisdiction

A development that has compounded the Indian Supreme Court’s inability to act as a constitutional guardian has been raised by Khaitan (2020b), who criticizes the Court for allowing its appellate function to diminish its constitutional adjudication function over time. This trend precedes the Modi regime but presents a clear institutional deficiency in the constitutional order as regards resistance to backsliding. The manner in which this institutional deficiency has developed over time is worth considering for Asian countries where calls have been made for the establishment of a constitutional court, such as Sri Lanka (Jayawickrama 2017).

4.1.5. Family and elite ties

Family and elite ties allow backsliders in various countries to instrumentalize the courts. For example, the low level of social legitimacy of the courts in the Philippines is said to partly derive from perceptions that judicial appointees are drawn from ‘the extended personal and political networks of presidents’ (Dressel 2024: 41). In Thailand, the Constitutional Court is closely tied to conservative ‘royal-monarchical networks’ (Dressel 2024: 41). In Indonesia, family ties are linked to broader concerns about the Constitutional Court’s increasing deference to the executive (Dressel 2024: 46).

Box 4.1. Family ties on the Constitutional Court of Indonesia

In Indonesia, the Constitutional Court delivered a highly controversial decision (No. 90/PUU-XXI/2023) in the ‘Almas case’ in October 2023 that reinterpreted the constitutional provision setting a clear minimum age of 40 for candidates, clearing the way for President Jokowi’s then-36-year-old son, Gibran Rakabuming Raka, to run as a vice-presidential candidate in the 2024 election (Putri and Khasyi’in 2023). The decision is viewed as having had a fundamental impact on the election (Pratama et al. 2025). The fact that the President of the Court, Anwar Usman, is Raka’s uncle through marriage should have automatically led to his recusal from the case. However, not only did he not recuse himself, but he led a majority decision that reinterpreted the clear constitutional rule in article 169(q) setting an age limit of 40 years for candidates to mean ‘being at least 40 years old or having previously/currently held a position elected through general elections, including regional head elections’. The majority decision was strongly criticized as departing decisively from the text of the Constitution, representing a sudden and unjustified departure from established precedent, violating procedural standards and demonstrating clear political bias. Following an investigation by the Ethics Council (chaired by former President of the Court Jimly Asshiddiqie), President Usman was dishonourably discharged from the role of chief justice. However, the decision itself was not affected, as the Ethics Council is not empowered to overturn court decisions (Muslikhah et al. 2024).

4.2. Tilting the electoral playing field

Making changes to the electoral system to heavily favour an incumbent is a common device used by anti-democratic governments to entrench their power. Such changes can include manipulating the boundaries of electoral districts to favour the ruling party (gerrymandering), distorting the electorate through selective enfranchisement or disenfranchisement as well as altering how surplus votes and seats are distributed between electoral winners and losers, employing various mechanisms to disqualify opposition politicians from standing for election, or reducing the transparency or independence of election management and oversight. Five examples from across the case-study cohort show how Asian countries align with, and also depart from, these global trends.

4.2.1. Changing the constitutional framework

Thailand’s most recent Constitution, adopted in 2017 following the 2014 coup d’état, is viewed as ‘the latest milestone in Thailand’s democratic decay’ and an exemplar of ‘abusive constitutionalism’ (Tonsakulrungruang 2024: 325–26). Rather than tilting the electoral playing field to one ruling party, as is commonly seen elsewhere, the new Constitution introduced a complex system of proportional representation favouring small- and mid-sized parties, perceived as allowing the proxy of the military junta, the National Council for Peace and Order, to compete against the largest existing parties (Tonsakulrungruang 2024: 333). As such, the 2017 Constitution significantly rolls back democratic progress, representing a serious decline from the 1997 ‘People’s Constitution’, viewed by many as Thailand’s most democratic constitution due to its attempt to provide for stable and representative government through a 5 per cent electoral threshold, party lists and the establishment of an elected senate (Martinez Kuhonta 2008: 375).

4.2.2. Gerrymandering

Concerns have been raised in India about gerrymandering—the redrawing of electoral districts to the advantage of one party. In the union territory of Jammu and Kashmir, whose special status (autonomy) was revoked by the Modi government in 2019, new constituency boundaries were finalized in 2022 by a panel established by the federal government. Some have claimed that the significant increase in the number of seats for Hindu-dominated Jammu compared with Muslim-dominated Kashmir was aimed at engineering a Hindu majority more favourable to the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP), as part of a broader project to transform India into an ‘ethnic democracy’ (Jaffrelot 2021; Daniyal 2023). In the state of Assam, three constituencies where the Bengali-origin Muslim community had significant political power were reserved for candidates belonging to scheduled castes and tribes, with the perceived aim of preventing Muslim-minority leaders from contesting elections, as well as redrawing boundaries to break up coherent Muslim-minority electoral blocs (Daniyal 2023).

4.2.3. Interference with electoral oversight

Questions have increasingly been raised about the independence of Indonesia’s electoral oversight institutions (ANFREL 2024a). For instance, some observers perceived the equivocation on the part of the General Elections Commission concerning the retention of vice-presidential debates as an attempted politically influenced measure to save Raka (running mate of the eventual victor, Prabowo Subianto) from debating the opposition’s seasoned vice-presidential candidate, Mahfud MD (Tanamal and Lai 2023).

Legislation enacted in India in 2023 altered the selection process for appointing members of the Election Commission: while the Supreme Court had required a collegium-like system through a selection committee comprising the prime minister, the leader of the opposition and the chief justice, the legislation replaced the chief justice with a Union cabinet minister. Criticized as problematically consolidating executive control of appointments (Chaturvedi 2024), this measure further undermines a critical institution 'once considered resolutely independent (Jain 2024). In Thailand, the Election Commission is viewed as increasingly embracing naked partisanship (Alderman 2024).

4.2.4. Political finance laws

In India, concerns were raised, including by the Election Commission, about a lack of transparency surrounding changes made to political financing through a new electoral bonds scheme in 2017. However, the measure was pushed through by the Modi government and, as the Supreme Court delayed hearing the case, the facts were fundamentally altered in time for the 2019 election, in which the BJP won its second outright majority (Sen 2024: 73). The controversy over electoral bonds also raises questions about the need for additional safeguards for amendments to electoral laws—an issue explored in the 2023 Designing Resistance report—such as a mandatory delay to allow for a public response from the electoral commission, possibly in the form of a report on the proposed legislation for parliamentary debate (Bisarya and Rogers 2023: 82). However, such a protective mechanism would require the presence of a fully independent commission.

4.2.5. Leveraging media dominance

During the 2024 presidential elections in Sri Lanka, the Asian Network for Free Elections identified concerns regarding media access, independence and balanced reporting, including about state-run media heavily favouring the incumbent; the state media’s biased reporting was further amplified by private media controlled by individuals with connections to the incumbent government (ANFREL 2024b: 12). The situation in Sri Lanka is reminiscent of how the ruling party Fidesz hollowed out independent media in Hungary through media buy-outs by its economic cronies (Zgut 2022). Similarly, Ruparelia (2024: 33, 35) states that India’s BJP and its corporate allies ‘gradually seized control of the mainstream media’ as part of the government’s drive towards hegemony, with opposition parties struggling to match the party’s ‘organizational abilities, financial resources, or media dominance’. Evidently, media dominance does not just happen but is linked to government suppression and intimidation of independent media (see 4.5.1: Silencing criticism).

4.2.6. Banning political parties

Thailand is a clear example of the observation made in the 2023 Designing Resistance report that militant-democracy mechanisms, such as political party bans, can easily be abused and should be approached with ‘extreme caution’ (Bisarya and Rogers 2023: 14). Party bans in Thailand have become commonplace, exemplified by the Constitutional Court’s recent dissolution of the largest opposition party, the Move Forward Party, on the basis that the party’s calls for reform of lèse-majesté laws violated the Constitution (Saksornchai 2024). If mechanisms to ban political parties are retained, they could be softened by broadening the procedure and increasing the number of actors involved—beyond the courts—in dissolution decisions, as well as by providing for reviews and reversing bans (Daly and Jones 2020). Evidently, many measures short of outright bans can be employed to disable political parties, including cutting off or freezing their financing (Herklotz and Jain 2024). The abuse of militant-democracy mechanisms is somewhat similar to the abuse of other constitutional provisions designed to provide protection against threats to the constitutional order, such as the abusive invocation of martial law in South Korea (see 4.4.3: Abuse of martial-law powers).

Box 4.2. Abuse of state resources by incumbents

Incumbents abusing state resources to maintain an advantage in elections is a common problem seen in the case studies. In Mongolia’s 2024 elections, for instance, the ruling Mongolian People’s Party reportedly took advantage of their incumbency and supermajority position, especially through a law on climate change and disaster relief and a plan initiated 60 days before the election that dispensed significant monetary assistance to rural communities. The government also raised the salaries of civil servants by 10 per cent and the pay of general service workers by 20 per cent (Altankhuyag and Gankhuyag 2024). Similarly, after Mongolia’s presidential elections in June 2021, an external electoral observation report noted ‘concerns related to the misuse of public resources and employees, which amplified the advantages of the ruling party’ (ODIHR 2021). The misuse of public resources is nothing new: research indicates that in Mongolia’s 2004 elections over 1,000 public employees were engaged in campaigning, spending a total of 4,761 hours canvassing votes (Ritchie and Shein 2017: 8). This approach, unlike more blatant vote buying seen in countries such as Indonesia (Muhtadi 2018; ANFREL 2024a), is not strictly illegal but is patently unethical and undermines both the democratic process and the impartiality of the public administration.

4.3. Weakening the power of the opposition in the legislature

The 2023 Designing Resistance report examines diverse gambits for weakening the power of the opposition in the legislature, ranging from procedural measures such as fast-tracking legislation or reducing the time allocated for opposition representatives’ speeches, to petty means such as cutting off opposition representatives’ microphones. The case-study cohort for this report reveals a range of additional measures employed by anti-democratic governments to diminish opposition power within the legislature. This section focuses on two key measures—co-opting opposition parties by inviting them into government and subverting parliamentary processes to bypass opposition scrutiny and fast-track legislation. This section also considers an unusual case of what might be called ‘excessive legislative empowerment’ in Taiwan, where legislation is in place that empowers the legislature to summon the president, private companies and even members of the general public to the legislature for questioning.

4.3.1. Co-opting the opposition

As Mietzner (2016: 210) observes, citing Slater and Simmons (2013), due to the system of coalitional presidentialism that has developed since the reformasi reforms of 1998–2002, Indonesian presidents have established a practice of inviting the maximum number of parties possible into government in order to achieve stable rule. This practice can create a ‘party cartel’ that leaves no effective opposition, diminishing deliberation, policy contestation and scrutiny of government action, as well as the prospect and visibility of alternative governments. This deficiency is evidently particularly severe where the president is a backslider intent on centralizing their power and disabling constraints on their power, as seen in the Jokowi administrations from 2014 through 2024, which appears to be continuing under the new president, Prabowo Subianto. The only party not currently in government is the Indonesian Democratic Party of Struggle (Harbowo 2024). Mietzner (2016: 210) further suggests that, by seriously attenuating the links between voters and parties, these dynamics can lead the electorate to turn to ‘outsider’ authoritarian-populist candidates, a prime example being the election of Rodrigo Duterte as president of the Philippines in 2016.

This raises the question of whether and how the constitutional order can be designed not only to empower an effective opposition in the legislature but also to require the presence of an effective opposition. One approach might be to grant the opposition specific rights and procedural powers, ensure that it is represented in important committees and state bodies, and provide it with adequate funding.

4.3.2. Subverting parliamentary processes

In many countries, the capacity of the legislature to hold the executive to account has already been diminished through the executive’s control of the political agenda. In India, for example, the BJP has weakened the opposition’s capacity to hold the executive to account by employing the parliament speaker role to the government’s advantage and abusing the procedure for passing so-called money bills, which can be fast-tracked, curtailing scrutiny and deliberation. Procedures have been abused in this way to pass extensive legislative projects that overhaul governance and implicate individual rights. For instance, the Lok Sabha (lower house) used this strategy to pass the Aadhaar (Targeted Delivery of Financial and Other Subsidies, Benefits and Services) Act 2016. This law provides the legal infrastructure for a system of biometric identification ostensibly aimed at better delivery of public services, benefits and subsidies to targeted beneficiaries while avoiding welfare fraud. Verma (2024) characterizes this subversion of the parliamentary process for law-making as ‘deliberation backsliding’, presenting the striking evidence that between the BJP’s return to office in 2019 and April 2024 a mere 13 per cent of all government bills introduced in the Lok Sabha were referred to parliamentary committees for in-depth examination and wider consultations with civil society and the public, compared with 60 per cent in the period 2004–2009 and 71 per cent in the period 2009–2014. In Mongolia, fast-tracking of legislation has also increased. Of the 260 laws passed from 2020 through 2024, 10 of them were adopted via an expedited process, without public consultation or adequate scrutiny (Mönkhtsetseg and Bilguun 2024).

Box 4.3. Legislative aggrandizement

Recent developments in Taiwan present an unusual example that runs counter to the general trend of executive aggrandizement, instead pursuing what might be called ‘legislative aggrandizement’.

Once Lai Ching-te of the Democratic Progressive Party won the presidential election in January 2024, the country entered into a period of divided government, with the legislature (Legislative Yuan) controlled by an alliance between the main opposition party, the Kuomintang—which governed during the authoritarian era—and the smaller Taiwan People’s Party. In May 2024 the Legislative Yuan passed highly controversial legislation, the Official Powers Law, expanding the legislature’s power to summon the president, companies and even members of the general public to the legislature for questioning, as well as giving lawmakers access to confidential documents (The Diplomat 2024).

At first glance, this law might appear to be a welcome measure, enhancing legislative scrutiny of the president. However, it also empowered the legislative majority to impose severe sanctions for contempt on those summoned to hearings if they were deemed to have concealed facts or made untrue statements, and to jail officials for up to six months for asking questions. Importantly, the system already contains a supervisory branch of government (the Control Yuan) with the power to investigate and impeach state officials. In addition to domestic criticism of the law, international scholars ‘sounded the alarm’, warning that the law posed a threat to the democratic system (The Diplomat 2024). On 25 October 2024 the Taiwan Constitutional Court declared multiple provisions of the amendment unconstitutional and limited the applicability of a range of other provisions.

This controversial legislation in Taiwan might not be as unusual as it first seems. For instance, as Argama (2021) has discussed, in 2016 Indonesia’s top legislature, the People’s Consultative Assembly, sought to reinstate state policy guidelines that had been removed from the text of the 1945 Constitution by the second major amendment during the democratizing reforms of 1998–2002. Although this manoeuvre failed, reversing that amendment would have shifted power back to the People’s Consultative Assembly, undermining the presidential system that was a central plank of the reformasi-era democratic reforms, along with other measures such as the establishment of the Constitutional Court.

4.4. Expanding executive power

The 2023 Designing Resistance report observes that measures to expand executive power serve two important functions: (a) offensively, broad powers empower the executive to implement policies that may help maintain their popularity; disable accountability mechanisms; or direct economic and other benefits towards themselves, their families and their loyal circle; and (b) defensively, executive power protects backsliders against challenges to their power, including from within their own party, the opposition or other state institutions such as the military (Bisarya and Rogers 2023). Although measures covered by the 2023 report, such as abuse of states of emergency, can be found among the case-study countries, this section contemplates two measures identified from the case-study cohort: (a) employing family ties to dissolve institutional boundaries and ‘supercharge’ executive control; and (b) militarizing civilian governance.

4.4.1. Family–state fusion

The 2023 report observes that the rise of political parties has undermined the institutional separation of powers, particularly when one party controls both the executive and the legislature (Bisarya and Rogers 2023: 77). This form of ‘party–state fusion’ (Khaitan 2020a) leaves opposition parties and independent oversight institutions as the principal sources of checks and balances. Sri Lanka’s experience in 2019 highlights an even more acute variant of this problem, where institutional divisions were seriously undermined through President Gotabaya Rajapaksa’s appointment of his brother Mahinda as prime minister (Shah and Gomez 2023: 53). This arrangement might be called ‘family–state fusion’.

As discussed above, issues have also arisen in Indonesia due to the familial ties between the president of the Constitutional Court and Vice-President Gibran Rakabuming Raka, the son of a previous president. Reilly (2024) has suggested that Raka’s election ‘hints at a potential resurgence of multigenerational political dynasties dominating Indonesian politics once again’. The entrenchment of dynastic politics is even more prevalent in the Philippines, where so-called fat or even obese dynasties (Mendoza, Jaminola and Yap 2019) have subverted the functioning of the 1987 Constitution, adopted in the post-authoritarian democratic transition. Yusingco (2022: 179) suggests that, unlike the single-headed Marcos dictatorship in place before the transition to democracy in 1986, dynastic politics has created many ‘small dictatorships’. These kinds of dictatorships can be seen in the election of Ferdinand ‘Bongbong’ Marcos Jr and Sara Duterte as president and vice-president, respectively, the progeny of two former presidents with authoritarian records.

4.4.2. Militarizing governance

Beyond Thailand—where the military’s tutelary control over the democratic system includes the constant threat of coups d’état—other states experiencing forms of ‘political militarization’ include the Philippines and Sri Lanka (Croissant et al. 2024: 8–9). This gambit can enhance executive power by marshalling considerable operational and organizational capacity, but it also raises the risk of a possible challenge to civilian backsliders (ordinarily, elected political office holders) by empowering the military (see Box 4.4).

Box 4.4. Divergent trajectories of political militarization

During his two terms, President Jokowi increased his use of the Indonesian armed forces, police and security services exponentially. For example, over 340,000 military and police personnel were mobilized in May 2020 to enforce Covid-19 repression measures nationwide (Setijadi 2021: 308). The legal framework for this expanded role for the military and police was bolstered in August 2020 when Jokowi issued Presidential Instruction 6/2020, which authorized the armed forces to patrol villages, ‘mentor’ local communities on pandemic protocols and dispense vaccines. Setijadi (2021) suggests that the deployment of military and police personnel in civilian roles was not merely an excess of the pandemic era but part of a much broader pattern reminiscent of the authoritarian practices of the regime of President Soeharto.

Importantly, Setijadi (2021: 308) suggests that President Jokowi was not motivated by a desire to revive the army’s Soeharto-era role, ‘but rather because [Jokowi] sees [the use of the security services] as an efficient and effective way to implement policies, as well as a means to appear strong and resolute’. The growing military influence in Indonesia during the Covid-19 pandemic contrasts with South Korea and Taiwan, where, despite their shared history of military rule, military involvement in Covid-19 responses was tightly controlled (Gibson-Fall 2021: 161). Croissant et al. (2024: 5) have observed that liberal democracies such as Mongolia and South Korea ‘have been mostly spared from political militarisation’.

4.4.3. Abuse of martial-law powers

Martial law refers to the temporary transfer of civilian governance to the military to address a specific crisis or emergency, and it ordinarily entails curbs on civil liberties and habeas corpus, as well as the imposition of curfews and even the extension of the jurisdiction of military courts to ordinary civilians. Many countries in Asia have significant experience where a civilian executive has abused martial-law powers to repress dissent. Among the eight case-study countries covered in this report, two prominent examples stand out—General Chun Doo-Hwan’s use of martial-law powers in South Korea to repress a citizen uprising following his coup d’état in 1980 (Kim 2003) and Ferdinand Marcos’s imposition of martial law in the Philippines from 1972 through 1986, a period marked by serious human rights abuses against the political opposition, student activists, journalists and other opponents of the governing regime (Human Rights Violations’ Victims Memorial Commission 2023). The contemporary abuse of martial-law powers is of more acute concern when a country has past experience of authoritarian rule.

Box 4.5. Declaration of martial law in South Korea

On the evening of Tuesday, 3 December 2024, South Korean President Yoon Suk Yeol declared martial law. Mere hours later, and following strong pushback by the National Assembly, citizens and key military personnel, President Yoon announced that martial law would be lifted. The episode was a striking example of how constitutional mechanisms to address emergencies can be abused by sitting executives to engage in a power grab. In this case, concerns about backsliding had intensified during President Yoon’s tenure (see 4.5.1: Silencing criticism), and he had been a lame-duck president since National Assembly elections in April 2024, in which the opposition Democratic Party won a landslide victory. On 14 December 2024 the National Assembly voted—with 204 votes in favour and 85 against—to impeach President Yoon. As a result of the impeachment, Yoon’s presidential powers were suspended, and Prime Minister Han Duck-soo assumed the role of acting president (Kim and Jett 2024). At the time of writing, Yoon also faced criminal investigation on possible rebellion charges, but he has not yet responded to a summons for questioning over his failed attempt to declare martial law (Kim and Jett 2024). Observers have questioned whether the institutional response to President Yoon’s declaration of martial law is evidence of the resilience of Korean democracy or of its fragility (Lee 2024; Yun 2024).

4.5. Shrinking the civic space

Shrinking the civic space—another tactic used by backsliders—includes attacks on the media, civil society organizations and the civil liberties of the electorate, which diminish vertical and diagonal channels for holding the government accountable. This section examines four examples: (a) silencing critical media; (b) employing colonial-era sedition laws to silence critics in India; (c) using blunt methods such as Internet shutdowns (e.g. India, Sri Lanka); and (d) passing laws on disinformation that provide expansive powers to the government to police content (e.g. legislation on so-called fake news in Indonesia).

4.5.1. Silencing criticism

As noted in The Global State of Democracy 2023, press freedom is under serious threat in many of the countries covered in the case studies in this report. The Government of South Korea, for example, has been criticized for barring access to, and funding for, public broadcasters viewed as critical of the president (International IDEA 2023: 30) and for establishing a special team of investigative prosecutors to target journalists for defamation (Lee, Cho and Jo 2024) and reducing the main regulator, the Korea Communications Commission, to two members by refusing to appoint opposition nominees (The Korea Times 2024).

Maria Ressa, the CEO of Rappler, the leading independent media company in the Philippines, continues to fight attempts to shut the company down (International IDEA 2023: 30, 97). A comparative analysis covering the use of strategic lawsuits against public participation (SLAPPs) in India, Indonesia, the Philippines and Thailand indicates that SLAPPs ‘overwhelmingly target activists, journalists, publishers, and leaders and members of local communities, and seek to stifle advocacy on environmental, labor, and human rights issues’ (Dutta 2020). Civicus (2024) reports that over half of all defamation cases in Mongolia focus on media outlets and journalists, often stemming from complaints by senior politicians, public servants and government agencies. Severe financial penalties have a chilling effect on public-interest journalism (Civicus 2024), resulting in ‘widespread self-censorship’ (ODIHR 2024).

In many countries, the prospect of prosecution—or even just interrogation—is sufficient to restrict media freedom. Harsher measures, including the targeting and killing of journalists critical of human rights abuses and corruption, are part of dominant patterns of undermining press freedom. In Thailand, critics are silenced through ‘violence and lawsuits’ (Tonsakulrungruang 2024: 341), including the selective and harsh application of lèse-majesté laws, facilitated by courts aligned with the establishment (Dressel 2024: 22). In Indonesia, publishing critical commentary entails the risk of state-sanctioned harassment and arrest (Warburton and Power 2020: 16).

4.5.2. Sedition laws

In post-colonial and post-authoritarian countries, backslider governments can make use of a legacy of ‘authoritarian shadows’ in the form of undemocratic legislation that would be very difficult to enact in the democratic era (Ahuja 2018). Sedition laws are a prime example of legislation that is frequently abused by governments across Asia (Clooney Foundation for Justice n.d.). In India, for instance, colonial-era defamation and sedition laws have been employed to silence critics. One study indicates that 95 per cent of the 405 Indians accused of sedition for criticizing politicians and governments in the period 2012–2022 were charged after 2014 (Hari 2022). Governments abuse these long-standing laws through selective prosecution and enforcement (Herklotz and Jain 2024).

4.5.3. Restricting NGO operations

Research suggests that Asia is a hotspot for increasing restrictions on non-governmental organizations (NGOs), with governments learning from one another in a process of ‘illiberal norm diffusion’ (Glasius, Schalk and de Lange 2020: 458; Chaudhry 2022: 574). The governments in several of the countries covered in the eight case studies have restricted the operation of both domestic and international NGOs, especially those that address human rights and governance issues. In India, restrictive rules introduced in 2010 have been further enhanced in an ‘administrative crackdown’ that led Amnesty International to cease its operations in 2020, the only country other than Russia in which it has done so (Chaudhry 2022: 583). In Mongolia, Sri Lanka and Thailand, draft laws seeking to curb NGOs have prompted significant protests and pushback from opposition and civil society actors, but governments have moved ahead with the laws despite this resistance (Fortify Rights 2024; Munkhbaya and Myagmar 2024: 81–83; Tegal 2024).

4.5.4. Criminalizing ‘fake news’

Democracies worldwide are faced with the difficult task of addressing how mis- and disinformation distort democratic discourse. The challenge of regulating such information provides an easy opening for backsliders to clamp down on critical speech under the guise of improving the information ecosystem. In Indonesia, for example, the penal code adopted in 2023 provides for imprisonment for up to two years for dissemination of ‘fake news’, vaguely defined as news that a person should know or suspect to be uncertain, exaggerated or incomplete (Harsono 2024). While some view this provision of the penal code as reasonable (Prahassacitta and Harkrisnowo 2024), the Constitutional Court ruled in May 2024 that the code should be repealed given that its vague provisions were open to abuse (Harsono 2024).

Box 4.6. Internet shutdowns and social media curbs