The Case for a Democracy Stack

Rethinking Digital Public Infrastructure for Democratic Societies

Discussion Paper 2, 2026

Resilient and trusted digital infrastructure is increasingly recognized as one of the key pillars of a more positive digital future; it also factors in broader conversations about countries’ pursuit of sovereignty and agency in the tech era. In particular, the concept of digital public infrastructure (DPI)—systems that serve as foundational digital building blocks for public benefit—is emerging as a fundamental layer in modern societies. Many governments and institutions have focused largely on the benefits that DPI can bring to public service delivery, economic development and inclusion, through the three core functions of (a) digital identity verification; (b) digital payments; and (c) secure data exchange, on top of which any number of products and services can be built. However, when it comes to the digital systems that underpin democratic societies, global normative shifts and geopolitical realities underscore a sense that we are at a crossroads. With digital authoritarianism on the rise and democratic institutions facing unprecedented pressures, DPI’s role in fostering democratic principles and engagement remains underdeveloped. This paper seeks to provide a starting point for multi-stakeholder discussions by offering a high-level overview of possible elements and considerations for democracy-enhancing DPI.

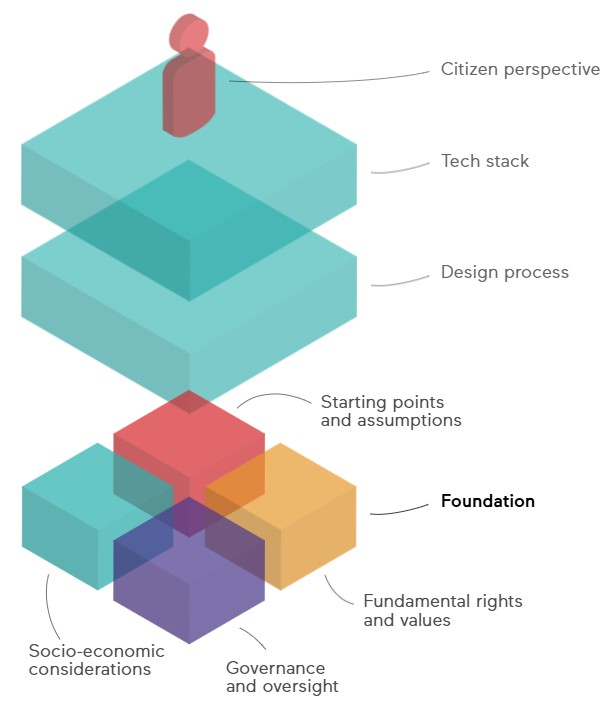

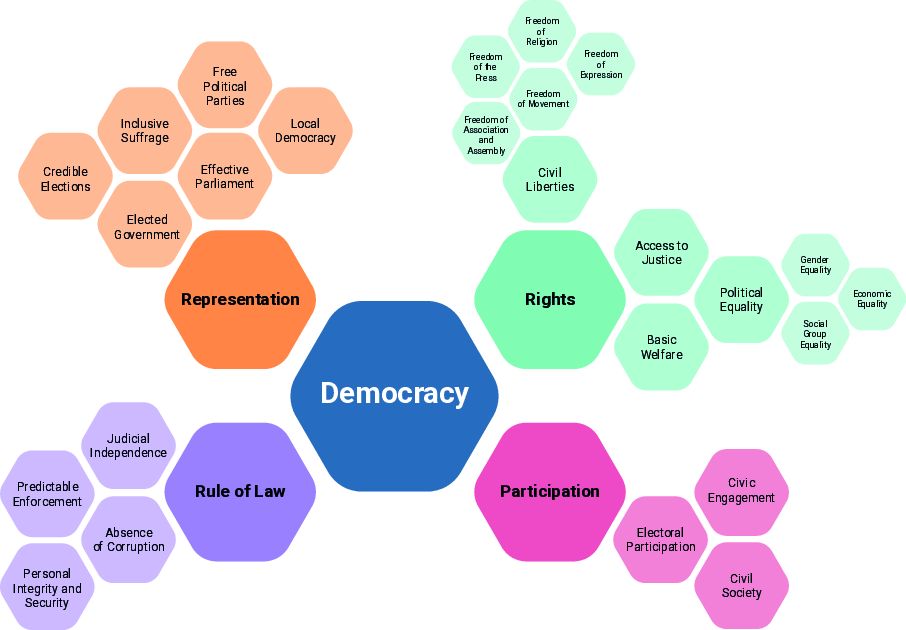

To address this gap, this paper raises the possibility of expanding the aperture—to consider the broader digital and information environment necessary for a functioning democracy, and to view those essential ingredients as part of DPI. In tech parlance, the term ‘digital stack’ generally refers to the set of layers that work together to deliver a digital product or experience. Drawing inspiration from Waag Futurelab’s concept of a ‘public stack’, the Democracy Stack may be framed as an approach in which all the layers that contribute to DPI systems—the foundational values, the design process, the tech itself, and the ways in which these layers position the citizen at both the top and the centre—are based on democratic values. Specifically, democracy-enhancing DPI could strive to ensure that technology respects and advances four key democratic indicators: the categories of Rights, Rule of Law, Representation and Participation.

In addition to DPI’s common areas of focus, which will continue to be essential for the public service delivery platforms that support citizen well-being (i.e. those three core functions of digital identity verification, digital payments and secure data exchange), a Democracy Stack raises the possibility of integrating additional core functions that are fundamental for democracy in the digital era. Each of the following proposed functions merits a deeper assessment of its potential to be reused ‘horizontally’ across sectors and its interoperability with other core functions in the stack (to allow government, the private sector and civil society to build solutions on top) and its democratic implications:

- A digital information ecosystem. Recognizing digital media’s profound influence on democracies and democratic processes, this function emphasizes the developing of digital public spheres for a healthier information environment. This could empower independent journalism, support public broadcasting models in the digital space and enable more varied civic spaces online for public discourse, in order to give users more options and choice over what they see and experience.

- Democratic participation and civic engagement. This function could enable citizens to engage actively in democratic processes, from voting and policy input to participatory governance. A combination of tools that allows citizens to cast their votes securely and transparently in elections or referendums—as well as to participate in public consultations, petitions and decision-making platforms—could support more-responsive and better-informed policies and increase civic engagement.

- Consent. An intentional approach to managing consent is vital, in order to ensure that citizens retain control and agency over their personal data and privacy, particularly in systems interlinked with identity verification and data sharing.

Despite the potential benefits, there could be risks in basing critical societal functions on DPI that is inadequately designed and implemented, or poorly maintained, with insufficient safeguards. Drawing on the Universal DPI Safeguards Framework stewarded by the United Nations, this paper examines possible risks spanning issues of privacy, cybersecurity and physical security, inclusion, the lack of adequate redress mechanisms, the erosion of trust, and civic disengagement. In addition, there are the structural vulnerabilities that may limit the effectiveness of safeguards, including weak rule of law and concentrations of power, weak institutions, technical shortcomings, the lack of sustainability measures and societal resistance to the concept of ‘public goods’.

To help balance the promise of democracy-enhancing DPI against the potential risks, this paper outlines four overarching tenets:

- Put users at the centre.

- Prioritize the democratic rights and values of all people, and strive to understand and balance democratic implications.

- Pursue a broad multi-stakeholder approach.

- Design, develop, implement and govern DPI in the public interest.

In pursuing these tenets, a number of principles may help navigate common challenges as DPI is contemplated, designed and rolled out in real-world settings. This paper touches on the principles proposed in the Universal DPI Safeguards Framework and adds additional considerations with regard to the democratic implications:

- Foundational principles: do no harm; do not discriminate; do not exclude; reinforce transparency and accountability; uphold the rule of law; promote autonomy and agency; foster community engagement and civic participation; ensure effective remedy and redress; and focus on future sustainability.

- Operational principles: leverage market dynamics; evolve with evidence; ensure data privacy by design; assure data security by design; ensure data protection; practise inclusive governance; and build and share open assets.

This paper does not prescribe a single model or path for any country. Rather, it seeks to provide a framework for reflection across diverse contexts, recognizing that each society will make different choices based on its history, institutions and democratic priorities. Customized approaches to DPI will need to be responsive to each state’s socio-political environment, institutional capacity, the maturity of its DPI initiatives, and its societal level of trust in the concept of public goods. While the Democracy Stack approach may be most appealing, or most feasible, in a country where there is reasonable trust and investment in the notion of public infrastructure, the existence of a highly digitalized society, where digital services are considered mainstream, can also open the door to new democratic challenges.

This exploration concludes with several key areas requiring further study:

- The democratic implications of a more widespread use of DPI, the potential tools and services that could be built on the linkages between existing and proposed core DPI functions, and key democratic indicators such as the category of Representation.

- The nuanced roles and dynamics involving private-sector stakeholders, particularly in situations where DPI efforts are perceived to be in competition with the core business model of existing large platforms.

- Future-proofing of DPI against shifts towards non-democratic practices, emphasizing layered safeguards with a focus on governance.

- Cybersecurity strategies tailored to safeguard DPI and ensure crisis resilience, including the need to identify, prioritize and plan for the services and registries that are essential for the continuity of government services and societal functions.

- Governance frameworks adaptable to diverse DPI ecosystems and responsive to the evolving dynamics of data and technology.

- The integration of emerging technologies such as artificial intelligence (AI), with careful attention to the implications for identity, privacy, inclusion and democratic integrity.

Although this is a complex topic beyond the scope of any one paper, weighing up the democratic implications of DPI today could help de-risk investments to avoid costly reversals and unintended consequences further down the road; enable a level of resilience and agency for countries seeking greater digital sovereignty, so as to buffer the impact of political and commercial dynamics on national digital systems; and help shore up DPI against misuse for repression and surveillance, or for the shrinking of civic spaces online. By viewing DPI as integral to societal well-being, democratic resilience and civic engagement, the Democracy Stack initiative aims to build on existing work in the DPI space to support global experts in charting a path forward that ensures our digital future aligns with our values.

Resilient and trusted digital infrastructure is increasingly recognized as one of the key pillars of a more positive digital future; it also factors in broader conversations about countries’ pursuit of sovereignty and agency in the tech era. In particular, the concept of digital public infrastructure (DPI) is emerging as a fundamental layer in modern societies. While the definition of DPI remains a topic of ongoing debate, the term is often used to refer to systems that serve as foundational digital building blocks for public benefit (Clark et al. 2025: 1). Many governments and institutions have focused largely on the benefits that DPI can bring to public service delivery, economic development and inclusion, through the three core functions of (a) digital identity verification, (b) digital payments and (c) secure data exchange, on top of which any number of products and services can be built.

However, when it comes to the digital systems that underpin democratic societies, global normative shifts and geopolitical realities underscore a sense that we are at a crossroads. Digital technologies define geopolitical power and economic competitiveness (Bria, Timmers and Gernone 2025: 10)—even as they define the day-to-day experience of people in relation to their societies and government. With digital authoritarianism on the rise, and democratic institutions facing unprecedented pressures, it is important to consider whether DPI’s role in fostering democratic principles and engagement remains underdeveloped. Framing DPI as an endeavour mainly concerning service delivery or access to the digital economy overlooks its profound implications for political participation, rights and democratic governance.

To begin to fill this gap, this paper explores the reframing of DPI as a supporter of democratic principles and an enabler of democratic engagement. Envisioning a digital stack approach, where layers work together to deliver a digital product or experience, Chapter 1 suggests moving beyond a narrow understanding of DPI towards the idea of a ‘Democracy Stack’, proposing conceptual components and possible additional functions grounded in democratic indicators. Chapter 2 examines possible risks associated with democracy-enhancing DPI that is poorly designed, implemented or maintained. Chapter 3 discusses suggested principles that countries should consider protecting rights and support democratic resilience, drawing on the Universal DPI Safeguards Framework. Finally, Chapter 4 suggests areas for potential future exploration.

This paper is not meant to recommend any definitive technical architecture or implementation instructions for a Democracy Stack. Rather, it seeks to provide a starting-point for multi-stakeholder discussions by offering a high-level overview of possible elements and considerations for democracy-enhancing DPI. The paper may be relevant to a diverse set of stakeholders, including government policymakers, international organizations, civil society actors, technology experts and digital rights advocates.

Furthermore, this paper does not prescribe a single path or model for any country. Rather, it seeks to provide a framework for reflection across diverse contexts, recognizing that each society faces unique circumstances that will shape its choices about:

- the design, architecture, implementation and governance of its own DPI;

- the effectiveness of safeguards; and

- the potential of the elements, explored in this paper, for supporting democratic principles and enabling democratic participation.

These circumstances include: a country’s history; its institutions; its democratic priorities; its domestic and geopolitical realities; the extent of its societal trust in government and the concept of public goods; its overall institutional capacity; its respect for rule of law; its support for DPI in terms of politics and funding; the strength of its private sector and/or civil society; the level of maturity in its DPI adoption; and its approach to foundational identity—the establishment and verification of core legal identity of individuals—and civil registry systems. This paper acknowledges that a Democracy Stack approach may be particularly appealing or feasible in a country with reasonable trust and investment in the notion of public infrastructure—but also that having a highly digitalized society, where digital services are considered mainstream, can open the door to new democratic challenges.

Finally, it is important to note that this Discussion Paper seeks to build on, and complement, the existing and ongoing work in the DPI space. While several of the elements examined here are often discussed in relation to DPI, this paper encourages the viewing of them through the lens of democratic principles, processes and participation. By exploring underdeveloped angles of the DPI approach, this paper aims to support global experts in charting a path forward, to ensure that our digital future aligns with our values.

1.1. Rationale for pursuing democracy-enhancing DPI

Stable and resilient democracies require trustworthy critical infrastructure. With democracies under pressure to deliver for their citizens, the fact that digital systems are increasingly becoming the structural backbone of our societies opens a world of possibilities. However, the speed, manner and context in which they are being developed exposes vulnerabilities that merit a deeper look, especially when it comes to our approach to DPI.

The question of who, ultimately, wields power over the digital infrastructure that impacts our daily lives (Berjon 2025) is concerning at a time when:

- companies are making decisions about digital systems that may not adhere to democratic principles, with minimal checks and balances;

- some states seek to promote alternative governance models for digital systems, including through their influence on international norms and infrastructure exports (Eaves 2023); and

- democracy is backsliding worldwide (Bisarya and Rogers 2023: 18).

Business-driven designs and decisions could have unintended consequences for individual rights, public safety and national security (Schaake 2020). Meanwhile, democratic societies are particularly vulnerable when concentrated technological power intersects with ideological interests (Bria, Timmers and Gernone 2025: 6), raising important questions about if, and in what way, DPI can weather changes in political leadership.

The online information environment provides an illustrative example of the stakes. There is a growing understanding of the corrosive effect that digital media can have on our democratic societies, with so much of our public life taking place on large-scale digital platforms—particularly those with advertising-based business models that can create incentives that sometimes conflict with democratic values (Pariser and Allen 2021) and which are susceptible to both domestic and foreign meddling. The rise of misinformation, disinformation and polarization—as well as the throttling of journalism—can erode trust in institutions; influence public opinion, elections and policies; make it hard for citizens to find common ground; and generally complicate democratic governance (American Academy of Arts and Sciences 2020).

This complex interplay of internal and external factors underscores a sense that the time may be right to take a broader view of DPI, which emphasizes the implications for democratic rights as well as the public spaces and tools that enable discourse and democratic engagement. Rooting democracy-enhancing DPI in smart safeguards today could help de-risk significant investments to avoid costly reversals and unintended consequences further down the road. This is particularly important as artificial intelligence (AI) and other emerging technologies shift the digital landscape at unprecedented speed. Additionally, taking a broader view of DPI could provide countries that seek a greater digital sovereignty with a level of democratic resilience and agency to buffer the impact of global political and commercial dynamics on national digital systems (Rodriguez, Price and Rodriguez 2023). It could also illuminate how DPI might be designed and grounded to deter actors who are tempted to misuse DPI for repression and surveillance or to shrink civic spaces online.

1.2. Defining DPI

DPI is an extensible and evolving concept (ODET and UNDP 2024: 8), with important variations in different organizations’ interpretations and areas of emphasis (Clark et al. 2025: 7–8). The World Bank Group’s definition aims to resonate across diverse country contexts and allow for flexibility as the concept evolves: ‘DPI refers to systems that serve as foundational, digital building blocks for public benefit’ (Clark et al. 2025: 8–9). In this definition, DPI:

- facilitates essential digital functions at society scale, which can be provided by the public and/or private sectors;

- adopts a building-block design that is typically modular, minimalist, open and interoperable, including the use of open standards and specifications to enable adoption and reuse across institutions, applications, sectors and borders; and

- embeds principles around user centricity, inclusion, privacy-by-design and transparent governance (Clark et al. 2025: 9).

Many governments and institutions have focused largely on the benefits that DPI can bring to public service delivery, economic development and growth, and inclusion—through the three core functions of digital identity verification, digital payments and secure data sharing, which make up the most common focus areas for DPI. However, there is no single model for the overall architecture of a country’s DPI (Clark et al. 2025: 33). Each country may take a different approach to defining the core functions that it deems foundational for its digital ecosystem, as well as to defining the objectives it ultimately seeks to achieve.

Given the seismic shifts taking place across democratic societies, this paper raises the possibility of expanding the aperture—to consider the broader digital and information environment necessary for a functioning democracy, and to view those essential ingredients as part of DPI (Price, Rodriguez and Rodriguez 2024). It proposes studying whether other elements and functions that are essential for society, and hard to provide through the market, may also be good candidates for public infrastructure, with the funding and other support that this would entail.

With this broader view in mind, this paper unpacks whether and how DPI could potentially serve as a driver for democratic societal well-being.

1.3. Proposing a Democracy Stack: Possible elements and democratic indicators

In tech parlance, a ‘digital stack’ refers to the layers that work together to deliver a digital product or experience. The DPI approach generally emphasizes interoperable DPI services working together, as a digital stack, to facilitate a variety of use cases across sectors (World Bank 2022: 2), as well as the need for broader ecosystem enablers (Clark et al. 2025: 4). Examples of digital stacks include the India Stack and Singapore’s National Digital Identity Stack (World Bank 2022: 2).

Similarly, the concept of a Democracy Stack could draw inspiration from Waag Futurelab’s definition for a ‘public stack’, framed as an approach where all the layers that contribute to tech—the foundational values, the design process, the tech itself and the ways in which these layers position people—are based on democratic values (Waag Futurelab n.d.a). In Figure 1.1, Waag Futurelab provides one of the most comprehensive visuals of a publicly oriented tech stack (Waag Futurelab n.d.e). While not suggesting a definitive architecture for a potential Democracy Stack, this section offers a useful starting point for the interaction between different elements up and down the stack, several of which this paper will examine in more depth.

1.3.1. The citizen-perspective layer

In this ‘citizen perspective’, the user at the top of the Democracy Stack is viewed as an individual in a democratic society, and the other layers in the stack play a part in shaping that relationship, determining whose interests are being served by the user’s interaction with tech (Waag Futurelab n.d.b). The top layer includes intangible elements, such as the influence the technology has on the user’s thoughts, the extent of the user’s access (based on algorithmic decisions) and the user’s position in relation to the rest of the stack (Waag Futurelab n.d.b).

Several of the elements examined in this paper ultimately influence the citizen perspective. The core DPI functions that lie immediately below the citizen-perspective layer play a key role in facilitating the individual’s ability to engage in their democratic society. This holds true for the three commonly mentioned core functions (digital identity verification, digital payments and secure data sharing) as well as for possible additional core functions, such as democratic participation and civic engagement, a digital information ecosystem and consent (see 1.4: Broadening the tech stack). Meanwhile, other elements play a role in ensuring that the user’s interests are being served in their interaction with tech. These include the democratic indicators and governance that anchor the foundation layer at the base of the stack (see 1.3.4: The foundation), awareness of the risks from DPI that is poorly designed or implemented (see Chapter 2) and the suggested principles to mitigate those risks (see Chapter 3).

1.3.2. The tech stack

The tech stack is composed of two layers—the tech layer and the context layer.

The tech layer includes the physical infrastructure at its base (such as Internet cables, GPS satellites, data centres and the computers they house to make up the cloud), along with devices, firmware and drivers, and operating systems; and at the top, the applications (Waag Futurelab Tech layers n.d.). Lying at the center of this tech layer, the core DPI functions discussed in this paper can be understood as an intermediate software layer that sits atop the physical infrastructure and below the platforms and applications that leverage DPI building blocks to deliver specific services (Clark et al. 2025: 7). Beyond the solutions (ranging from e-commerce platforms to digital public services) that can be built on the three most commonly mentioned core DPI functions, the integration of additional functions—to facilitate more-informed democratic engagement—could enhance the tech stack by opening up new possibilities (see 1.4: Broadening the tech stack).

Meanwhile, the context layer within the tech stack provides the virtual cement that holds together the different elements of the tech stack, through:

- the protocols and standards that make interoperability, communication and data exchange possible;

- the data and algorithms at each layer of the tech stack, which provide overall services for the users; and

- the security measures against misuse (Waag Futurelab n.d.c).

This paper proposes principles (see Chapter 3) and raises open questions (see Chapter 4) that address ways to approach the different elements of the context layer holding the tech stack together.

1.3.3. The design process

By making choices about both the tech and context layers—determining each device, application and protocol, and the ways in which they work together—the design process has a large influence on whose thoughts and interests are digitalized (Waag Futurelab n.d.d). These choices could be improved by understanding the potential risks of DPI that is poorly designed or implemented (see Chapter 2), as well as by employing suggested principles and safeguards (see Chapter 3). A variety of design methods may be appropriate in a broader Democracy Stack, including co-creation and public participation approaches that ultimately help to give users agency in deciding and implementing solutions (Waag Futurelab n.d.d).

1.3.4. The foundation

At the base of the Democracy Stack, digital tools and services should be grounded in decisions that resound in all layers of the stack. This includes ensuring that fundamental rights and values are respected (Waag Futurelab n.d.f), that all interested stakeholders are involved, that it is clear to what end you are digitalizing (Waag Futurelab n.d.h), and that governance and oversight are included (Waag Futurelab n.d.g).

To set common benchmarks for those rights, values and decisions originating in the foundation layer, the Democracy Stack could strive to ensure that DPI advances the following four broad democratic categories outlined in the Global State of Democracy Initiative, as depicted in Figure 1.2.

The categories may be summarized as follows:

- Rights. This category includes equitable access to service delivery, inclusion and non-discrimination, freedom of choice, agency, fair competition, freedom of expression and privacy. For example, under Estonia’s X-Road secure data highway—which facilitates information exchange between different government entities, as well as between government and the private sector—Estonian citizens are the owners of their own data (Vseviov 2023).

- Rule of Law. This category includes transparency, openness, accountability, absence of corruption, justice, security and access to redress. For example, more-transparent, automated government processes can help to hinder corruption (Vseviov 2023).

- Representation. This category includes credible elections free of disinformation, foreign interference or the distortion of generative AI; free and fair competition between political parties; a balance of power between the legislature and executive; inclusive suffrage; and the ability to practise democracy at the local level. For example, citizens would potentially be better represented if the terms of governance for the information platforms that, de facto, determine the extent of their informed participation in democratic processes were determined by an intentional multi-stakeholder process, rather than by a small group of corporate executives (Schaake 2020).

- Participation. This category emphasizes participation in democratic processes, which could include voting and policy input, a civil society perspective and civic engagement (including through the creation of civic spaces online). For example, the ability to cast votes online, for Estonia’s first-ever parliamentary election, made voting more accessible not only for tech-savvy youth but also for those with difficulty getting to the polling stations—the elderly, people with disabilities, caregivers, shift workers and citizens working overseas (Vseviov 2023).

Among prominent global actors in the emerging DPI field, the discussion of the approach and implications of different solutions is currently more developed under the Rights and Rule of Law categories, while the Representation and Participation categories would also benefit from deeper examination.

With this common understanding of the democratic values and indicators at the foundation of the Democracy Stack, this paper proposes principles and safeguards (see Chapter 3) and raises questions that merit more research (see Chapter 4), in order to ensure that decisions made around DPI design and deployment foster democratic rights and engagement.

1.4. Broadening the tech stack: Additional core functions

The tech stack that lies within the Democracy Stack framework (see 1.3.2: The tech stack) merits a deeper look, particularly as it is the home of DPI’s core functions, which can power any number of applications across different sectors. Current DPI discussions among governments and institutions often revolve around the three common functions on top of which public, private or civil society actors can build services and solutions: digital identity verification, digital payments and secure data sharing. Some countries are already finding their current DPI stack to be an enabling element of both democracy and the overall functioning of the state (Leosk 2022; Vseviov 2023). These three core functions will continue to be necessary, especially for the public service delivery platforms essential for advancing citizen well-being.

In addition to these three widely accepted functions, the Democracy Stack framework opens the intriguing possibility of integrating additional core functions that could advance democratic engagement and participation. While not an exhaustive list, this section highlights added functions that stakeholders may wish to consider further, with their potential to be reused horizontally across various sectors, and with interoperability with other core functions and possible applications in mind.

1.4.1. A digital information ecosystem

Exploring a democratic information ecosystem as a core DPI function recognizes the critical influence that digital media have on democratic societies. Stakeholders will need to assess several questions:

- What is the digital information environment necessary for a functioning democracy (Price, Rodriguez and Rodriguez 2024)?

- How can we change our approach to digital spaces, so that they contribute to building a shared reality instead of pulling communities apart in alternative, separate realities (Pariser and Allen 2021)?

- To what extent should governments—and other sectors—play a role in building digital infrastructure to support a healthier information environment?

- How could other DPIs in the stack connect and interoperate with elements of an openly available democratic information ecosystem on which government, civil society and the private sector can innovate? What are the potential implications?

At the fundamental level, this will require examining how the free flow of information could:

- facilitate better communication between governments and citizens (UNDESA and Ainbinder 2024);

- ensure that the media can provide high-quality reporting and operate without censorship or undue influence; and

- provide varied civic spaces online for public discourse.

The process of filling in the gaps unaddressed by market solutions could emphasize approaches that strengthen open and democratic societies, such as by:

- informing users;

- enabling groups to assemble and deliberate (Zuckerman 2020a);

- allowing citizens to mobilize groups for civic action online and offline (Zuckerman 2018);

- giving users choice about how and when they share their personal information online and how and where they are tracked; and

- providing users with more choice, insight and transparency regarding what they see and experience online (Zuckerman 2020b).

To begin to answer the questions posed above, one could look to the movement that is under way to develop our digital public spheres proactively (Rajendra-Nicolucci, Sugarman and Zuckerman 2023). This approach recognizes that, just as with the public spaces in our physical communities (such as parks and libraries), online public spaces and institutions can play critical roles in weaving and maintaining our social fabric, providing places for discourse to unfold, access to essential resources (for people who could not otherwise access them) and even the groundwork on which private industry can build (Pariser and Allen 2021). This approach leans towards a large suite of localized, community-specific and public-serving institutions, instead of one main communication platform (Pariser and Allen 2021).

As a first step, digital public spheres could include information services with a mission-driven agenda (Pariser and Allen 2021). Wikipedia, as a free online encyclopaedia, is a notable nonprofit example (Zuckerman 2020a). Systems for reporting factually accurate news could also potentially be considered as DPI that supports informed participation in a democracy, on top of which products and services can be built (Price, Rodriguez and Rodriguez 2024). In one example, a group of local journalists in the Philippines built the digital news outlet Rappler (and the Rappler Communities app, connected to its news feed) in search of a trusted, shared reality based on facts. Built on the open-source, secure and decentralized Matrix protocol, the app has the potential to become a global independent news distribution outlet (Jordaan 2024). It would also be possible to imagine DPI including public broadcasting models (Pariser and Allen 2021), possibly drawing from the public service vision of the United Kingdom’s early British Broadcasting Corporation (BBC) and the ability to complement commercial media as exemplified by the United States’ Public Broadcasting Service (PBS) and National Public Radio (NPR) (Zuckerman 2020a). In addition to content creation and support for independent journalism, DPI could help create new tools and services that market-based news models have been unable to support—for example, a web browser to navigate the web more safely (Zuckerman 2020a).

Digital public spheres could also include civic spaces online, where people could talk, share and interrelate without those relationships being distorted and shaped by profit-seeking incentive algorithms. There are numerous examples of digital spaces that host civic conversations at the local level, such as the Front Porch Forum’s social media platform, which services mainly towns in the US state of Vermont, and Smalltown platform, which hosts closely moderated local civic discussions (Rajendra-Nicolucci, Sugarman and Zuckerman 2023). In the Netherlands, the PublicSpaces coalition of public media organizations, along with filmmakers and the Dutch arm of Wikimedia, are building open-source technology to facilitate community dialogue and discussion in a publicly governed model (Pariser and Allen 2021).

There may be an opportunity to unite several of these threads in the growing movement towards decentralized, federated or distributed communication platforms, aiming to provide users more options. For example, the Initiative for Digital Public Infrastructure (iDPI) at the University of Massachusetts Amherst proposes a digital public sphere that consists of many different platforms with a wide variety of sizes and purposes, which users can navigate with a loyal client: a user-controlled application that brings together feeds from multiple platforms and allows them to post, follow and curate across services from a single interface (Rajendra-Nicolucci, Sugarman and Zuckerman 2023). Rather than encouraging users to abandon today’s large social media platforms, this more diverse ecosystem includes existing platforms alongside a flourishing ecosystem of smaller online platforms—with different goals, norms, governance and potential uses—to give people access to many more spaces, and to empower them to choose where, and how, they participate for a more sustainable and resilient digital public sphere (Rajendra-Nicolucci, Sugarman and Zuckerman 2023).

This may be a particularly interesting framework, given the emergence of a host of alternative social media services, such as BlueSky, Mastodon, Free Our Feeds and Social Web Foundation. While they do not all support the same protocol, this is not necessarily an insurmountable barrier. For example, iDPI’s loyal client, Gobo.social, is a user-tunable filtering system that can talk to social media services built on different protocols, so long as they provide the hooks for interoperability through their application programming interface (API). The users of Gobo.social are able to choose which algorithms and thresholds eliminate, or include, content from their feeds (Zuckerman 2020a). This is an area that could benefit from public infrastructure funding, because, with that interoperability, it would be important to build clients and algorithms that provide users with greater control (Zuckerman 2020b). Free Our Feeds and Social Web Foundation are also reportedly working on ways to aggregate sites that use different tech (Agarwal 2025).

There are a number of other challenges that will likely need to be addressed. Securing user buy-in may be difficult in polarized environments already mistrustful of government or ‘elite media’, especially without a broad-based consensus on the need for news as a public good for the health of democracies (Zuckerman 2020b). A diverse ecosystem composed of various platforms with different norms and governance models, from traditional board models to self-governance by members (Pariser and Allen 2021) and beyond, will require a thoughtful overall governance approach. Finally, funding could take a range of forms, such as via a tax on ‘targeted advertising’ (American Academy of Arts and Sciences 2020), the creation of a publicly funded nonprofit corporation (Pariser and Allen 2021) or a micropayments system for quality content.

1.4.2. Democratic participation and civic engagement

At the heart of the Democracy Stack concept, it may also be worth considering a core function that enables citizens to engage actively in democratic processes, from voting and policy input to participatory governance. This function would be closely interlinked with that of a democratic information ecosystem, as informed participation and spaces for civic discourse are essential prerequisites for democratic engagement.

This effort could start with the technologies and processes that allow citizens to cast their votes securely and transparently in elections or referendums. For example, Estonia’s

This function could also include tools for public consultations, petitions and decision-making platforms, in order to enable communities to engage in sustained dialogue, resolve differences and participate collectively in the decisions that affect their lives (Price and Rodriguez 2024). Alongside established approaches, such as participatory budgeting, new and promising growth areas are emerging: one example is citizen participation in reducing carbon emissions (Leal Garcia 2023: 8). Fortunately, this exploration can benefit from numerous existing examples. For example, in 2023, Taiwan’s Alignment Assemblies project used the open-source platform Pol.is to gather public views on AI (Price and Rodriguez 2024). In another example at the national level, more than 100 million people participate each year in the Brazilian Senate’s online offerings, whereby residents can propose and subscribe to draft legislation, comment on proposed legislation, submit questions for witnesses appearing before congressional committees, and submit new student-proposed policies (Price and Rodriguez 2024). At the level of US states, New Jersey used the All Our Ideas platform to co-create its AI policy with the public (Price and Rodriguez 2024). Meanwhile, through the Better Reykjavik project, over 20 per cent of the city’s population participates in proposing urban improvements, with the city’s leadership committed to considering the top-five public-rated ideas (Price and Rodriguez 2024).

Such projects hint at an initial sense of the challenges in this space. These include lack of understanding—of why well-designed opportunities for public participation can lead to better decision making, and of how to deploy them efficiently—as well as unawareness of the digital literacy, cybersecurity measures and commitment from institutions that are needed to incorporate public input genuinely (Price and Rodriguez 2024). Balancing ease of access and secure authentication of citizens represents a potential risk (Leal Garcia 2023: 9), especially as the lack of reliable, widely available, secure digital ID systems is a major challenge for credible online participation. Countries will also need to examine closely the implications and possible risks of linking identity and participation in political processes in their particular context (see Chapters 2 and 3); for example, some jurisdictions may wish to ensure that electoral management bodies stay independent from ministries involved with running national identity systems, although this implies trade-offs in terms of efficiency and costs.

Importantly, these projects also help illustrate how a combination of these tools and platforms might lead to more responsive decision making, increased civic engagement and better-informed policies—crucial elements of both a healthy digital ecosystem and a stronger democracy (Price and Rodriguez 2024).

1.4.3. Consent

An intentional approach to consent is necessary to support individuals’ rights to privacy and desire for agency over their personal data (Digital Impact Alliance 2024). Put simply, citizens still need to be in control.

It is up for debate whether consent should be considered as a standalone function for the deployment of a data-protection architecture and related technologies, as consent is already deeply interlinked with both identity verification and data sharing.

For example, electronic signatures (e-signatures) are sometimes grouped together with digital identity, particularly for transactions requiring user content (Clark et al. 2025: 17). Whether implemented through standalone systems or through an ID system (Clark et al. 2025: 18), e-signatures can essentially authenticate transactions by providing digital versions of signatures that are legally equivalent to handwritten signatures—for example, giving consent for a telehealth provider to view an electronic medical record (Clark et al. 2025: 17). Different types of e-signatures can provide different levels of assurance or security, from low (such as clicking an ‘I accept’ box) to high (such as e-signatures based on digital signature technology that uses public key infrastructure) (Clark et al. 2025: 17).

Meanwhile, when considering data sharing, strong user-consent mechanisms, privacy controls and access management are necessary to mitigate the risk of over-sharing sensitive data in certain systems (Clark et al. 2025: 40). A range of different data-sharing methods exists, depending on the type of consent required for a particular system. For example, intermediated methods, involving third-party platforms or entities that facilitate data exchange on behalf of individual data subjects, include regulated schemes such as India’s Data Empowerment and Protection Act 2023 or the European Union’s Data Governance Act 2022 (Clark et al. 2025: 41–42). Meanwhile, decentralized methods give individuals greater control over how their personal data is accessed and used—such as through digitally verifiable credentials, personal data vaults and other content-based data-sharing systems (Clark et al. 2025: 43).

In another example, Estonia has a consent service that features a workflow where citizens can give authorization to a third party (for example, on a private-sector portal) for one-time access to their data held on a government registry, similar to open banking scenarios (e-Estonia 2024). Estonia is also in the process of implementing a data-tracker tool, allowing citizens to see which part of the government has been accessing their data, and under which scenarios. With the advance of AI, Estonia is exploring the possibility of mechanisms or configuration models for digital government, where citizens can choose—in a portal—how much digital government they want, ranging from very little to full automation with predictive and preventive behaviours, and for which activities.

Some democracy experts caution that many issues for DPI may stem from the issue of consent, particularly:

- if the possession of a digital identity is mandatory by law, or necessary in practice, in order to access services such as voting, healthcare or participation in online political deliberation;

- if the required use of biometrics (for example, in order to vote) leads to privacy risks, including mass surveillance; or

- if the user in question, such as a child, is not in a position to provide consent.

When considering the role of consent in a Democracy Stack, it may be advisable to view it as existing along a spectrum, within which users might opt out of providing biometrics or be offered analogue alternatives, to mitigate the risk of further excluding already marginalized populations. It might be necessary to minimize the linkage with identity authentication where not strictly necessary (for example, to participate in civic spaces), and to use privacy-enhancing technologies to minimize the amount of personal information shared.

2.1. Identifying the risks

Despite its potential benefits, there may be inherent risks in basing critical societal functions on DPI that is inadequately designed and/or implemented, or poorly maintained, with insufficient safeguards (ODET and UNDP 2024: 12). While this section discusses possible risks along a spectrum of severity, it does not imply that negative outcomes are inevitable. Rather, referring to the Democracy Stack framework (see Chapter 1), it suggests that understanding the range of potential risk scenarios can help to highlight areas where safeguards are essential to promote citizens’ interests, and to ensure that decisions made around the design and deployment of DPI foster democratic rights and engagement.

One overarching risk that cuts across those detailed below is the possibility that, with changes in political leadership or direction, DPI systems could be particularly vulnerable to political shifts that weaken democratic safeguards or repurpose DPI for non-democratic ends. In addition to eroding trust in a country’s own DPI, such shifts might raise the risk of providing models for the misuse of DPI in other countries. While this paper will suggest principles and safeguards that may help shore up DPI against such scenarios (see Chapter 3), this remains an area ripe for future exploration (see Chapter 4).

It is also important to keep in mind that, ultimately, country context is a critical factor. Risks and structural vulnerabilities can vary significantly across country contexts, and their effects are not evenly distributed across society (ODET and UNDP 2024: 5).

The following examination of risks draws extensively on the Universal DPI Safeguards Framework developed through a global multi-stakeholder effort stewarded by the United Nations, adding elements with an emphasis on democratic implications.

The most relevant types of risk might be summarized as follows:

- Privacy risks. DPI systems can create a ‘honey pot’ of personal and sensitive information (Digital Impact Alliance 2024). Privacy breaches may lead to, not only identity theft and fraud by bad actors, but also potential government overreach—enabling governments to access data unlawfully and misuse it for surveillance (ODET and UNDP 2024: 12) and for the political control and repression of targeted groups, particularly activists (Access Now 2023), minorities (Turner Lee and Chin-Rothmann 2022) and marginalized communities (Collings and York 2023).

- Cybersecurity and physical security risks. Viewing DPI as critical infrastructure for democratic societies and processes carries with it a considerable cybersecurity risk from service outages and sector-wide disruptions, as well as from malicious exploitation such as sabotage, unlawful surveillance, suppression of speech and assembly, espionage and the destabilization of nations (ODET and UNDP 2024: 12). As societies become more highly digitized, tools for democratic processes (like voting) could become a target of attacks from political opponents; however, in reality, many of these risks could be perpetrated by both internal and external actors. Physical insecurity may result if people’s identities, places of residence, movements (ODET and UNDP 2024: 12), transactions (from payments to political donations) and political activities are traceable. For vulnerable people in particular—those who express dissenting opinions, or asylum seekers and stateless persons—this could result in persecution, discrimination, denial of protection or services, and/or physical retaliation or harm (ODET and UNDP 2024: 12).

- Risks to inclusion. Discrimination of any kind can reduce participation in democratic processes, access to essential services and economic empowerment. The same consequences can result from unequal access due to the digital divide, shortfalls in infrastructure, socio-economic barriers, service gaps in some geographical areas, language barriers or disability (ODET and UNDP 2024: 13). In this context, it is critical to consider potential risks around the use of digital identities. This is especially the case if full legal identity verification is the basis for access to services or digital spaces (whether mandatory or de facto), where the digitalization of ID and other similar systems carries the risk of perpetuating existing disenfranchisement (ODET and UNDP 2024: 13)—particularly if a country’s foundational identification and civil registration systems are discriminatory (Rodriguez, Price and Rodriguez 2024) or where populations lack (or prefer not to have) a legal identity. When enrolment in DPI systems is mandatory, onerous or impossible, vulnerable individuals who may need to rely on others for assistance may be excluded (ODET and UNDP 2024: 13). DPI systems that restrict individuals’ control over their personal data can threaten their human agency and autonomy, especially if they have little understanding of the possible use and reuse of the data, as can mandatory data provision, which can violate human rights and civil liberties in some jurisdictions (ODET and UNDP 2024: 13).

- Erosion of trust and civic disengagement. While a certain level of societal trust is needed for the adoption of DPI, poor execution of digital tools and systems can quickly reverse any gains. Cybersecurity measures for DPI are imperative if it is to be viewed as critical infrastructure for democratic societies and processes. Digital distrust may arise from known or perceived risks to safety and inclusion (ODET and UNDP 2024: 14). Political-participation tools deemed unsafe, inefficient or irrelevant may dampen adoption and civic engagement. The persistent lack of trusted information and civic discourse online may complicate democratic governance and stymie civic engagement by eroding trust in institutions like the media, the judiciary and elected officials (Serrano 2024); that lack could also negatively influence public opinion, elections and government policies (Funk, Vesteinsson and Baker 2024). Even decentralized or federated social media spaces carry the possible risk that removing misinformation may become more difficult if thousands of smaller platforms allow offensive content, or if toxic communities gain more control over the spaces they inhabit (Zuckerman 2020b; Donovan 2020). Meanwhile, polarization and echo chambers created by poorly designed or opaque algorithms on social media and news platforms make it harder for citizens to find common ground (American Academy of Arts and Sciences 2020).

- Lack of recourse. Inadequate remedies and mechanisms of redress, for when rights are violated, erode public trust in DPI and reduce adoption rates (ODET and UNDP 2024: 13).

2.2. Identifying structural vulnerabilities

Underlying these risks, several structural vulnerabilities at the systemic level may limit the effectiveness of safeguards (ODET and UNDP 2024: 12). These are summarized below.

- Weak rule of law and concentration of power. Without sufficient respect for the rule of law, legal, regulatory and ethical frameworks may be unable to mitigate risks adequately (ODET and UNDP 2024: 14). If DPI amplifies the political, social and economic power of those who control it, this could undermine the institutions responsible for the rule of law and evade checks and balances, potentially leading to abuses (ODET and UNDP 2024: 14). Concentrations of power may be in the form of monopolies that could inhibit innovation (ODET and UNDP 2024: 14) or lie within executive agencies of government, for example.

- Weak institutions. Insufficient institutional capacity, mechanisms and resources can diminish the effectiveness and legitimacy of safeguards, through failure to implement necessary policies and practices (ODET and UNDP 2024: 14).

- Resistance to the concept of public goods. A cultural mistrust in the concept of public goods—or lack of experience with well-functioning public goods—may impede the willingness of authorities to support and invest in DPI, as well as hinder its adoption by users.

- Technical shortcomings. Technology systems that are not designed to ensure safety and inclusivity, and to prevent harm, diminish the effectiveness of a safeguards approach.

- Unsustainability. DPI that does not take long-term sustainability into account—be it financial, environmental or in terms of partnerships (to prevent vendor lock-in)—ultimately poses risks to those who have invested in, and rely on, its services and limits adoption by potential users (and users of other DPI) (ODET and UNDP 2024: 15).

With a clearer grasp of the range of risks associated with DPI that is inadequately designed or implemented, or poorly maintained (see Chapter 2: Risks and structural vulnerabilities), this chapter pivots to finding ways to mitigate those risks. Although the following is not an exhaustive list, the tenets, principles and safeguards suggested here may help navigate common challenges as DPI is contemplated and rolled out in real-world settings.

Referring back to the Democracy Stack framework (see Chapter 1), principles and safeguards aim to:

- confirm that the citizen’s interests are being served in their interaction with technology;

- improve the context layer—including the protocols, standards, data, algorithms and security measures—that holds the tech stack together;

- inform choices made in the design process that determine whose thoughts and interests are digitalized; and

- ensure that the foundational decisions made around DPI design and deployment foster democratic rights and engagement.

While the grounding of DPI in smart principles and safeguards will require effort at the outset, that effort is strongly advised in order to avoid unintended consequences and costly reversals further down the road.

3.1. Overarching tenets

There are four overarching tenets to which democracy-enhancing DPI should strive to adhere, throughout the DPI lifecycle as well as throughout the enabling ecosystem that supports it. These are:

- Put users at the centre. By viewing the user as an individual in a democratic society (Waag Futurelab n.d.b), DPI should employ human-centred design principles—including user research, co-creation, prototyping, piloting and iterative design—to ensure that DPI is user-friendly, accessible and meets the needs of diverse populations (Clark et al. 2025: 2–3).

- Prioritize the democratic rights and values of all people, and strive to understand and balance democratic implications. DPI should seek to ensure that the use of technology positively shapes and facilitates users’ relationship with, and participation in, a democratic society. It should consider how both domestic and external developments in the tech ecosystem, as well as the offline situation in the physical world, might affect that relationship and the overall health of democratic societies.

- Pursue a broad multi-stakeholder approach. DPI with society-wide implications will have the best chance of succeeding if all sectors are involved, including the private sector, government representatives, civil society organizations, academia, funders and other stakeholders.

- Design, develop, implement and govern DPI in the public interest. DPI should strive to serve all of society by embedding principles of, and employing tools and strategies for, a public benefit orientation in both technical design and the supporting ecosystem (Clark et al. 2025: 12–13).

Fortunately, translating these overarching tenets into actionable recommendations can benefit from existing work in the DPI space. The next section touches on a number of principles in the Universal DPI Safeguards Framework that can help to guide this effort.

3.2. Principles

In pursuing these overarching tenets, the Universal DPI Safeguards Framework and its interactive tool lay out foundational and operational principles that can inform the effort to balance the promise of democracy-enhancing DPI against the potential risks. With the Democracy Stack approach in mind, this section proposes additional perspectives on several of those principles below, keeping in mind that the effectiveness and outcomes of safeguards may vary from country to country.

There is one important caveat: systems cannot be built on the assumption that democracy will maintain itself. There are no clear-cut answers as to how DPI may be future-proofed, in the event of political shifts that weaken democratic safeguards and practices, or against abuses in general. In this area, which calls for more exploration, critics point out that technical and design solutions are likely to be insufficient for correcting what is, essentially, a problem of politics or human nature. However, digital systems and their underlying ecosystems must still be shored up as much as possible against the possibility of abuse. A number of suggestions are woven throughout the principles below, ranging from design approaches (such as the decentralization of services and the minimizing of access to personal data) to legal and legislative safeguards for resisting democratic slippage, to the creation of independent oversight agencies and the fostering of a more-engaged civil society as a counterweight.

3.2.1. Foundational principles

These may be summarized as follows:

- Do no harm. Integrate a human rights-based framework throughout the DPI life cycle, in order to anticipate and mitigate potential harms (ODET and UNDP 2024: 23), including those affecting democratic rights and participation.

- Do not discriminate. Address access issues and mitigate risks for vulnerable and marginalized communities and those who opt out (ODET and UNDP 2024: 23); include diverse input into how DPI systems are designed and implemented; and anticipate measures required for emerging technologies, such as ensuring that the data on which AI tools are trained is as complete, accurate and representative as possible, so as to lessen the impact of bias and discrimination.

- Do not exclude. Provide individuals with a choice of channels (digital and non-digital) for accessing services; ensure that access is not limiting, conditional or mandatory, whether explicitly or in practice (ODET and UNDP 2024: 23); and encourage democratic engagement and participation by building users’ digital literacy with regard to the use and implications of relevant DPI systems.

- Reinforce transparency and accountability. Develop DPI with democratic participation, promote fair market competition and avoid vendor lock-in (ODET and UNDP 2024: 23); consider establishing oversight and accountability mechanisms, with robust, well-resourced institutions—such as data-protection agencies or independent bodies—to offer citizens effective redress (Digital Impact Alliance 2024); ensure respect for privacy and data-protection laws; protect and improve protocols, and/or protect the independence and security of digital infrastructure; and encourage transparency in the algorithms that can affect access to public services and democratic engagement.

- Uphold the rule of law. Ground DPI with a clear legal and legislative basis, and with legal and regulatory aspects embedded into its design, supported with capacity for sector-specific tailoring, implementation, oversight and regulation by law (ODET and UNDP 2024: 23). Techno-legal frameworks could include measures protecting data and implementing cybersecurity standards, such as the Indian Supreme Court’s rulings to protect individuals’ privacy rights (Digital Impact Alliance 2024), as well as the interoperability frameworks that support broader democratic engagement and global compatibility, such as Estonia’s Interoperability Framework (Leosk 2022).

- Promote autonomy and agency. Consider that the concept of agency exists at both the individual level—for example, so that anyone, on their own or with assistance, can take control of their data, exercise choice and contribute to their society’s well-being (ODET and UNDP 2024: 23)—and the national level.

- Foster community engagement and civic participation. Ensure that individuals and communities, including those at risk, can participate at critical junctures and provide feedback in an environment of trust (ODET and UNDP 2024: 23); and enable citizens to participate in democratic processes, whether through voting, public consultations, participatory decision making or engaging with public services.

- Ensure effective remedy and redress. Make complaint-response and redress mechanisms, supported by administrative and judicial review, accessible to all, without fear of reprisal (ODET and UNDP 2024: 23).

- Focus on future sustainability. Anticipate the financial, social and environmental sustainability needs for limiting long-term or inter-generational harms (ODET and UNDP 2024: 24) and ensure the availability of services for those who have come to rely on them.

3.2.2. Operational principles

Operational principles may be summarized as follows:

- Leverage market dynamics. Foster an environment where public and private-market players can compete and introduce diverse solutions that cater to the emerging needs of all people across society (ODET and UNDP 2024: 24).

- Evolve with evidence. Conduct independent, transparent and continuous assessments, as well as due diligence or audits, which engage with people to cease rapidly or provide remedy for activities that contain heightened risks or harms.

- Ensure data privacy by design. Embed legal, regulatory and technical principles that enforce core privacy principles (e.g. minimization of data collection, provisions to delink, ability to limit observability) and enact legal safeguards around them (ODET and UNDP 2024: 24); and consider using privacy-enhancing technologies and other means to build DPI that responds to a structure where identity verification is viewed as being on a spectrum, and where users are empowered to control their personal information.

- Assure data security by design. Incorporate and continually upgrade security measures, such as encryption or pseudonymization, to protect personal data (ODET and UNDP 2024: 24); employ technical safeguards, such as decentralized data storage, to hinder non-state actors, rogue government actors or authoritarian regimes from gaining access or manipulating personal data (Digital Impact Alliance 2024; for example, Estonia’s approach to DPI features decentralization of services in which there is no ‘central’ database but rather common protocols that facilitate interoperability between different parts of the government); and establish a legal framework for data security (ODET and UNDP 2024: 24).

- Ensure data protection during use. Ensure that personal data is processed or retained lawfully and transparently only by authorized personnel within a legal framework (ODET and UNDP 2024: 24).

- Practise inclusive governance. Employ transparent and participatory multi-stakeholder governance models (ODET and UNDP 2024: 24).

- Build and share open assets. Embrace the sharing and reusing of open protocols, specifications, digital public goods and associated knowledge (ODET and UNDP 2024: 24).

Overall, while the task of mitigating the risks associated with poorly designed and implemented DPI can seem daunting, the principles described above provide a pathway for avoiding some of the most common obstacles. Still, this remains a dynamic and evolving space. The next Chapter (4: Potential areas for further exploration), identifies several questions and challenges that remain to be addressed in pursuing democracy-enhancing DPI.

By introducing the concept of a Democracy Stack, this paper has attempted to begin unpacking whether DPI may be reframed as an enabler of democratic principles and engagement in the current challenging environment. By moving towards a broader understanding of DPI that includes the digital and information environment necessary for a functioning democracy, the Democracy Stack provides a framework for understanding the interaction between the different conceptual elements explored in this paper. These range from the core DPI functions that facilitate a person’s ability to engage in their democratic society, to the design process and principles that help mitigate inherent risks, and which help ensure that citizens’ interests are being served in their interaction with tech, and to the democratic values and indicators at the foundation of any effort.

Nevertheless, this initial exploration only begins to scratch the surface. This final chapter, while not exhaustive, identifies several critical areas demanding further inquiry as we move from a conceptual to a more practical vision for the Democracy Stack approach. That vision includes:

- the broader democratic implications of potential tools and services built on integrated core DPI functions across sectors;

- the nuanced roles and competitive dynamics involving private-sector stakeholders; and

- strategies for future-proofing DPI against non-democratic shifts or misuse.

Additionally, this chapter emphasizes the imperative of robust cybersecurity measures tailored to diverse national scenarios, the evolution of adaptable governance frameworks suitable for varied DPI ecosystems, and the potential democratic impacts—both beneficial and detrimental—of incorporating AI and emerging technologies into DPI systems.

4.1. Overall implications for democracy

Additional thinking is needed about the possible implications of the more widespread use of DPI for democratic rights and engagement. To address gaps, this would include a deeper analysis of how the proposed additional core DPI functions may be reused horizontally across various sectors, as well as more thinking about the potential tools and services that could be built on top of the interoperability between existing and proposed core DPI functions (see 1.4: Broadening the tech stack). As part of this assessment, it will be important to understand when linkages between different functions in the stack may be helpful or harmful in real-world scenarios (see Chapter 2: Risks and structural vulnerabilities). Further thought is also needed on the Representation category of indicators that parse the potential role of technology in areas such as the balance of power between legislative and executive branches (see 1.3.4: The foundation).

4.2. The private-sector factor

DPI is fundamentally a multi-sector effort. Private-sector actors have a key role to play across the DPI ecosystem, including for:

- innovating and building solutions on top of the DPI infrastructure;

- participating in the design, implementation, multi-stakeholder governance and adoption of DPI initiatives;

- financing DPI projects; and

- providing cybersecurity solutions.

However, when DPI efforts are perceived to be in competition with the core business model of existing large platforms, there arises a number of challenges. DPI services need to have a high level of quality and ease of use to be accepted by users, and established platforms or services may very well have the resources, technical capacity and user-base to outpace them.

Design principles focusing on interoperability, extensibility and a shift from platform-centric models to protocol-based systems can help players—from small startups to large enterprises—to participate, compete and innovate within the ecosystem (Massally, Matthan and Chaudhuri 2023). For example, the democratic information ecosystem proposed in this paper envisions a scenario where existing platforms function alongside smaller online platforms, emphasizing the inherent value of options and choice, rather than encouraging users to abandon today’s large social media platforms (see 1.4: Broadening the tech stack). Still, it will be an ongoing challenge to find the right balance of interests, incentives and cooperation when it comes to the private sector role in DPI.

4.3. Future-proofing DPI

There are outstanding questions about the extent to which DPI can be future-proofed against political shifts. DPI is ultimately vulnerable to the influence of those with control or authority over public infrastructure. Whatever the political situation is today, it is imperative to think about how to mitigate the potential risks associated with DPI (see Chapter 2: Risks and structural vulnerabilities) in future scenarios where democratic safeguards are weakened or DPI is repurposed for non-democratic ends; this imperative underscores the importance of layered protections.

The decentralization of services may certainly help. But, as most architectures have proven susceptible to capture, the layering of multiple reinforcing safeguards to create checks and balances, with a strong emphasis on governance, can at least make it more difficult to misuse DPI systems. For example, one could consider an approach that includes federated architecture and multiple distributed databases, governed by an independent oversight agency with a multi-stakeholder board, in a vibrant ecosystem with strong legal and legislative safeguards of core principles and interdependent non-state actors as a counterweight. The downsides may be slower innovation and higher costs and complexity. Finding the right approach will require a careful balancing act and will vary by country.

4.4. Cybersecurity

Cybersecurity measures for DPI are imperative if DPI is to be viewed as critical infrastructure for democratic societies and processes. Each country’s focus may be slightly different when considering its own security and crisis resilience. For example, some countries may choose to implement a zero-trust architecture, in order to limit internal lateral movement and prevent unauthorized access to sensitive data (Rose et al. 2020). Others may focus on sovereignty, avoiding reliance on proprietary technology to which they do not own the code or underlying hardware, and possibly establishing their own servers or national hybrid cloud.

Regardless of the approach taken, countries will need to identify, prioritize and plan for the services and registries that are essential for the continuity of government services and societal functions. These may vary according to the country and crisis scenario—for example, whether the threat is existential or local, whether there is an instance of hacking or a hostile takeover, or whether a natural disaster is occurring, etc. In scenarios involving warfare or occupation, approaches may differ according to a country’s territorial depth, geographical location or other criteria. For example, Estonia stores key government information in ‘data embassies’ beyond its borders and is studying how to run government services from these locations. Meanwhile, Ukraine’s decision to migrate its core registries outside the country and into the cloud has been critical in keeping data secure and government services running in the currently ongoing conflict with Russia. In any scenario, it will be important to have back-up and offline systems in place.

4.5. Governance

There is currently no global overarching model or ‘one size fits all’ approach to DPI governance. Suggested frameworks that offer a good starting point include those outlined in the Universal DPI Safeguards Framework (ODET and UNDP 2024: 36), the Ash Center for Democratic Governance and Innovation’s ‘Best Practices for the Governance of Digital Public Goods’ (Eaves et al. 2022) and the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development’s ‘Principles for Public Administration’ (OECD 2023). Governance structures will vary depending on the problem a country is trying to solve, the legal framework under which they operate, the resources available and their overall digital capabilities (Eaves et al. 2022: 1)—although certain elements may be advisable across the board, such as multi-stakeholder involvement and the independence of any oversight bodies.

Given the diverse nature of DPI ecosystems, further thinking is needed about the democratic implications of the various parts making up the Democracy Stack. Each layer in the tech stack alone has its own designers, builders and organizational forms; and the varying dynamics between the stakeholders at each layer suggest the need for a more granular understanding (Waag Futurelab n.d.i). Furthermore, certain elements of a Democracy Stack may require innovative forms of governance. For example, the unique logic and nature of digital data raises interesting questions about whether different layers (for example, the platform and cloud, or the data itself, or the application layers) or different verticals (for example, health data vs social networks) should be treated differently from a regulatory perspective; such questions may upend traditional thinking around concepts such as ownership (Plunkett 2022). Meanwhile, this paper’s examination of a democratic information ecosystem as an additional core DPI function envisions various platforms with different governance models. Such complexities could lend weight to calls for some sort of independent body to oversee the Democracy Stack. Regardless, they underscore the need for further research on the governance of democracy-enhancing DPI.

4.6. AI and other emerging technologies

Finally, as AI and other emerging technologies are introduced into the DPI ecosystem, there needs to be thinking about the implications for democracy, both positive and negative. For example, on the one hand, AI could possibly:

- enable real-time, data-driven decisions by processing vast amounts of data at rapid speed;

- support DPI in serving a diverse, multilingual population by overcoming language barriers;

- allow for tailored public service delivery; and

- help governments to anticipate risks proactively (Shetty and Murty 2024).

AI agents could also potentially serve as a shield to enhance the cybersecurity of DPI systems (Nagar and Eaves 2024).

On the other hand, there are a number of questions that need to be examined in relation to AI’s exposure to DPI’s treasure trove of data and information. For example, in envisioning a digital information ecosystem as a core DPI function open to all users (see 1.4.1: A digital information ecosystem), it will be necessary to think about its exposure to AI systems that train on publicly available content. It may be possible to imagine linking content to micropayments as one way to address the monetization problem around open content, although this requires further analysis. In addition to questions of visibility, control and transparency, the issue of identity and the ways in which our systems are built to recognize and validate citizens could also continue to be problematic. Citizens who are not ‘readable’ to technology systems in a standardized way—such as individuals who are stateless, lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender or queer (LGBTQ+), neurodivergent, have disabilities, lack documentation, or who may not want to be documented officially (for personal or security reasons)—risk being further disenfranchised. In sum, the integration of AI and other emerging technologies requires further exploration.

Viewing DPI through a democratic lens—one that prioritizes the implications for individuals and societies, as well as the public spaces and tools that enable discourse and democratic engagement—is a complex undertaking that will require a deeper examination beyond the scope of any one paper. The Democracy Stack approach outlined here suggests one possible framework for ensuring that DPI is grounded in widely accepted democratic indicators and is responsive to the current challenges faced by democracies. Further discussion is needed to ensure that the elements proposed in this paper both are functional and advance democratic objectives in real-world scenarios.

Recognizing the potential for digital stacks to serve as one of the key pillars of a more positive digital landscape, it is hoped that the considerations raised in this paper can help catalyse dialogue around possible gaps in the overall DPI approach. Ultimately, weighing up the merits of a Democracy Stack is not merely a technical endeavour; it represents a fundamental commitment to democratic integrity, civic empowerment and societal well-being in our increasingly interconnected digital future.

Abbreviations

| AI | Artificial intelligence |

|---|---|

| DPI | Digital public infrastructure |

| iDPI | Initiative for Digital Public Infrastructure |

This paper has been developed by Silvana Rodriguez. The author is grateful for the insights received from Benjamin Bertelsen, Digital Public Infrastructure Manager in the Chief Digital Office of the United Nations Development Programme; Ethan Zuckerman, Professor and Director of the Digital Public Infrastructure Initiative at UMass Amherst; Marianne Diaz Hernandez, digital rights strategist, researcher and writer; and Madis Tapupere, Chief Technology Officer of Core Banking for the Luminor Group and former Government Chief Technology Officer in Estonia’s Ministry of Justice and Digital Affairs. Their perspectives and feedback were instrumental in developing the approach outlined in this paper, although their inclusion here does not constitute their endorsement of the ideas proposed in this discussion paper.