Assessing the State of Democracy in the Pacific

Exploring the Meaning and Practice of Democracy in the Pacific Islands Countries

We are proud of our democratic traditions and values in the Pacific. Across our region, democracy begins in local communities and associations. It is expressed in the way we relate to each other and come together to make communal decisions. As political leaders, we also know that challenges remain. With limited resources, we continue to work towards democratic systems that are fit for purpose—systems that allow us to represent the interests and needs of our people effectively, that support us in responding to our people’s concerns with care and that help us plan ahead for the sustainability of future generations and our environment.

This report is a welcome and candid discussion of the state of democracy in the Pacific, including in my own country, Vanuatu. There are lessons for all countries in the region. I welcome the opportunity to share these lessons with the global community of democracy practitioners, including fellow parliamentarians.

I thank the Australian National University’s Department of Pacific Affairs and the International Institute for Democracy and Electoral Assistance for their constructive partnership with parliamentarians and other political actors across the region in developing this report and for their continuing support in promoting democracy across the Pacific.

Honourable Ralph Regenvanu MP

Parliament of Vanuatu

The International Institute for Democracy and Electoral Assistance (International IDEA) and the Department of Pacific Affairs at the Australian National University (ANU) are each well known for producing policy-relevant knowledge based on cutting-edge research and diverse expertise. We are therefore very pleased that our two organizations have partnered to present this timely analysis of the state of democracy in the Pacific region.

Since 2017, International IDEA’s Global State of Democracy Initiative has leveraged a broad framework of indicators to assess global, regional and national trends in democratic performance. These data, which rank among the most trusted sources on the quality of democracy, also complement International IDEA’s work on developing democratic capacity in governments, parliaments, electoral authorities and civil society worldwide.

International IDEA collaborates with international and national organizations, academia and practitioners across its research and programming. These partnerships help to ensure that the Institute’s work to understand and support democracy is informed by global comparative expertise as well as local knowledge.

This publication is an excellent example of such cooperation. As a leading international centre for applied research, teaching and outreach on the Pacific, ANU’s Department of Pacific Affairs has a wealth of expertise on democratic practices in the Pacific region. This report reflects our organizations’ shared aim to support dialogue and substantive efforts at national and regional levels to advance democratic governance in the Pacific.

The Pacific region is often underrepresented in global data, including in matters of governance. The diverse experiences of Pacific countries offer valuable insights into the meaning and practice of democracy. Understanding the challenges, opportunities and innovations surrounding democracy in the Pacific is not only crucial for supporting democracy in the region, but also helpful for understanding democracy everywhere. This report represents an important contribution towards that goal.

Professor Helen Sullivan

Dean, College of Asia and the Pacific, ANU

Dr Kevin Casas-Zamora

Secretary-General, International IDEA

There is clear support for democracy in the Pacific Islands region, but there are also reasons to be concerned about its contemporary practice. In some parts of the region, the institutional context in which elections are run is compromised by weak policy and legal frameworks and ineffective tools, such as out-of-date electoral rolls. Politics is intensely personalized, often involving direct relationships between voters and politicians that complicate accountability and transparency standards and expectations. Politics is also dominated by older, male voices.

The complexity of Pacific democracy is rarely captured in global datasets. In fact, Pacific Island states are often completely excluded, because of either their relatively small population size or the lack of reliable data. This has significant consequences for the understanding of democratic practice in the Pacific, and the completeness of the global understanding of democracy.

Chapter 1 of this report examines the data compiled through International IDEA’s Global State of Democracy on four Pacific states—Fiji, Papua New Guinea, Solomon Islands and Vanuatu—and reflects on its completeness in the light of research and knowledge compiled by researchers working in the region.

In Fiji we found that the 2022 election represented a milestone in democratic renewal following a period of authoritarian rule. However, this came with initial turmoil and has been followed by a disappointing continuing absence of parliamentary transparency. Voter turnout has declined and municipal elections have not been organized since 2006. Women’s political representation has also declined, driven in part by deeply entrenched social norms that paint women as peripheral to the political sphere. These norms have become increasingly evident in toxic commentary about women politicians in social and traditional media.

In Papua New Guinea, we note that the basic infrastructure to run elections continues to be degraded and inadequate. While the country is heterogeneous and there is significant variability in the conduct of elections across provinces, in some parts the electoral roll is woefully inaccurate; the boundaries used to determine electoral districts are unclear, if not rigged; polling boxes are stolen or destroyed; and the volume of electoral petitions is so high that they cannot be processed in good time. There is often a weak link between the selection of a Member of Parliament and the formation of a government, leading to poor parliamentary performance and policymaking. This has follow-on effects for service delivery, accountability and transparency.

In Solomon Islands, we find that geopolitics has influenced democratic quality. Dissent over the national government’s foreign policy—in particular its ‘switch’ to allegiance to China from Taiwan in 2019—has been at the forefront of national debates and conflicts, including destructive riots in 2021. Public financial mismanagement during the Covid-19 years was subsequently revealed by the country’s national audit agency, raising questions about accountability and justice.

Finally, in Vanuatu, we note that high levels of political instability have had detrimental impacts on the country’s economy, service delivery and parliamentary effectiveness. Without judicial intervention, politicians in Vanuatu would struggle to resolve the conflicts of interest that regularly erupt in parliament. Deeply held conventions normalize men’s influence over women’s vote choice. Coupled with the practice of communal decision-making, and the perception that the vote is not secret, many women are often left without political agency. Voter bribery is becoming increasingly prevalent.

Chapter 2 considers what democracy means in the broader Pacific by examining six common features: grassroots democracy, smallness, localized politics, cohabitation, political marginalization and democratic innovation.

In many parts of the Pacific, ordinary citizens see and practice politics in their everyday lives—what we call grassroots democracy, reflecting strong local democratic cultures and influencing the way they perceive and interact with more formal processes. Leadership is localized through kinship groups (e.g. a clan chief) or the village. While these practices favour older male leaders, there are opportunities for political participation through peer networks such as church groups and youth organizations. These can create space for issues-based advocacy and social change.

The size and scale of countries in the region has a direct impact on Pacific democracy. Political systems are defined by hyper-personalization in the relationship between voters and their leaders, making it difficult for some social groups to express dissent or practice political resistance. As a consequence of their size, Pacific states can either be extremely politically fluid—where Members of Parliament easily change their allegiances—or fixed in elite power, with government officials holding multiple roles of influence. This blurs the separation of powers, bestows unchecked power on the elite and creates heady systems of clientelism and patronage.

In the localized political systems of the Pacific, voters have come to expect their representatives to deliver basic services rather than focus on national development. This expectation has been fuelled by the rise of constituency development funds, or discretionary pools of money for politicians to spend on their electorates, which now comprise sizeable proportions of national budgets. Localized politics also comes at the expense of more developed political party systems. Political parties in the Pacific operate in accordance with the internal logic of their own context, and often survive because of the charisma and popularity of their leaders.

Democracy operates through the cohabitation of democratic and traditional governance norms across the Pacific. Political order, and customary, religious and non-traditional political norms coexist, sometimes harmoniously, sometimes in tension. One example of this is evident in ideas of communal voting, where the vote is seen as an obligation undertaken on behalf of one’s community, which may be in conflict with the idea that the vote is an individual right. This has implications for electoral integrity.

Democracy is also monopolized by particular social groups in the Pacific, marginalizing other groups such as women, young people, diverse SOGIESC communities and ethnic minorities. In a region with high rates of climate-related displacement, the marginalization of migrant populations is becoming increasingly salient.

Perhaps because of these multifaceted and complex challenges, Pacific societies have adapted and innovated. Political institutions are newer and less bound by tradition, which opens up space for interesting and experimental democratic innovations such as dedicated seats for representatives of resettled communities now based in Fiji in the Kiribati parliament, or for women and young people in some local councils. In Bougainville, community government is designed to be gender equal, and in Papua New Guinea judges in the Supreme Court and national courts can act on their own initiative to uphold human rights.

How can global conceptions of democracy be adapted to include a more nuanced understanding of Pacific contexts? We suggest first, that the region be considered on its own. There is so much diversity within the Pacific that it warrants separate attention from the larger geographic construct of ‘the Asia Pacific’, or the even larger ‘Indo-Pacific’. Second, we suggest that greater investment be made in research across the region, and more particularly in the less studied countries of Polynesia and Micronesia. Finally, we suggest that the common features of democracy in the Pacific outlined above be incorporated into future frameworks of democracy.

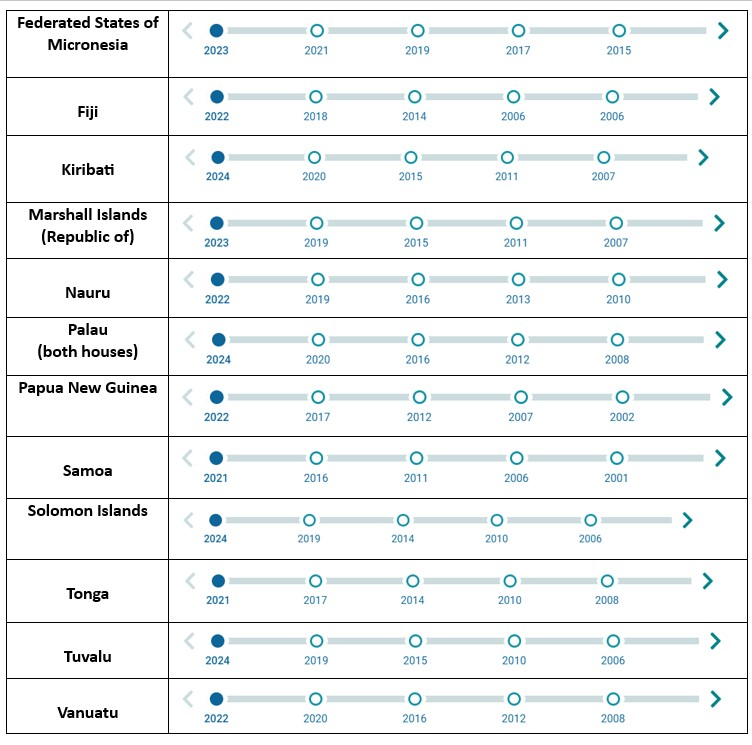

There is clear support for democracy in the Pacific Islands region. Most Pacific elites have signalled their commitment to democracy through a solid track record of regularly scheduled national elections (see Figure 1) and peaceful transfers of power. Among voters, the vibrancy of Pacific democratic culture is most evident in the high election turnouts, even when this is voluntary.

Despite this, however, there are also reasons to be concerned about the state of democracy in the region. Administering elections can be very difficult in often geographically complex contexts with highly dispersed populations. Many electoral management bodies are under-funded by national governments and a number are institutionally weak and lack the technical capacity to run an election in the absence of support from international organizations and donor funding (see Arghiros et al. 2017). This institutional context has led to recurrent problems with both the policy and the legal frameworks that support elections. Absentee voting, for example, is either non-existent or ineffective despite the existence of significant diaspora populations. In addition, the practical tools by which elections are run, such as voter rolls, are commonly out of date or misused. In smaller polities, politics becomes intensely personalized and direct relationships between voters and politicians can complicate the process of making claims on the state (Corbett 2015a). Parties tend to be weakly institutionalized, which reinforces the atomized nature of politics in much of the region (Wood 2016; Wood et al. 2023). Politics is dominated by older, male voices, and the region as a whole has the lowest level of women’s parliamentary representation in the world (Palmieri & Zetlin 2020).

This paints a complex picture of democracy—one in which an enduring public commitment to democracy and political institutions is undermined by a tangible disconnect between citizens and the democratic institutions that comprise the state, exacerbated by a lack of diverse representation in politics. This complexity, however, is rarely captured in global datasets. In fact, Pacific Islands states are often excluded completely, either due to their size or the lack of readily available data.

Since 2017, International IDEA has published successive reports tracking the Global State of Democracy (GSoD). These reports use a range of data compiled at the global level to assess countries’ progress and setbacks on various indicators of democratic standards. While ranking countries or comparing across countries can be problematic, the GSoD focuses on the internal changes evidenced in a given country over time. In addition to global analyses, International IDEA has produced regional analyses, including for Asia and the Pacific. The intention behind applying global frameworks to regions has often been to assist governments, civil society organizations (CSOs) and others to further promote democratic governance in ways that are suited to local contexts. The representativeness of Pacific analysis, however, is limited by the data collated at the global level. This has significant consequences for both the understanding of democratic practice in the Pacific and the completeness of global conceptualizations of democracy.

Box 1. Global State of Democracy Indices

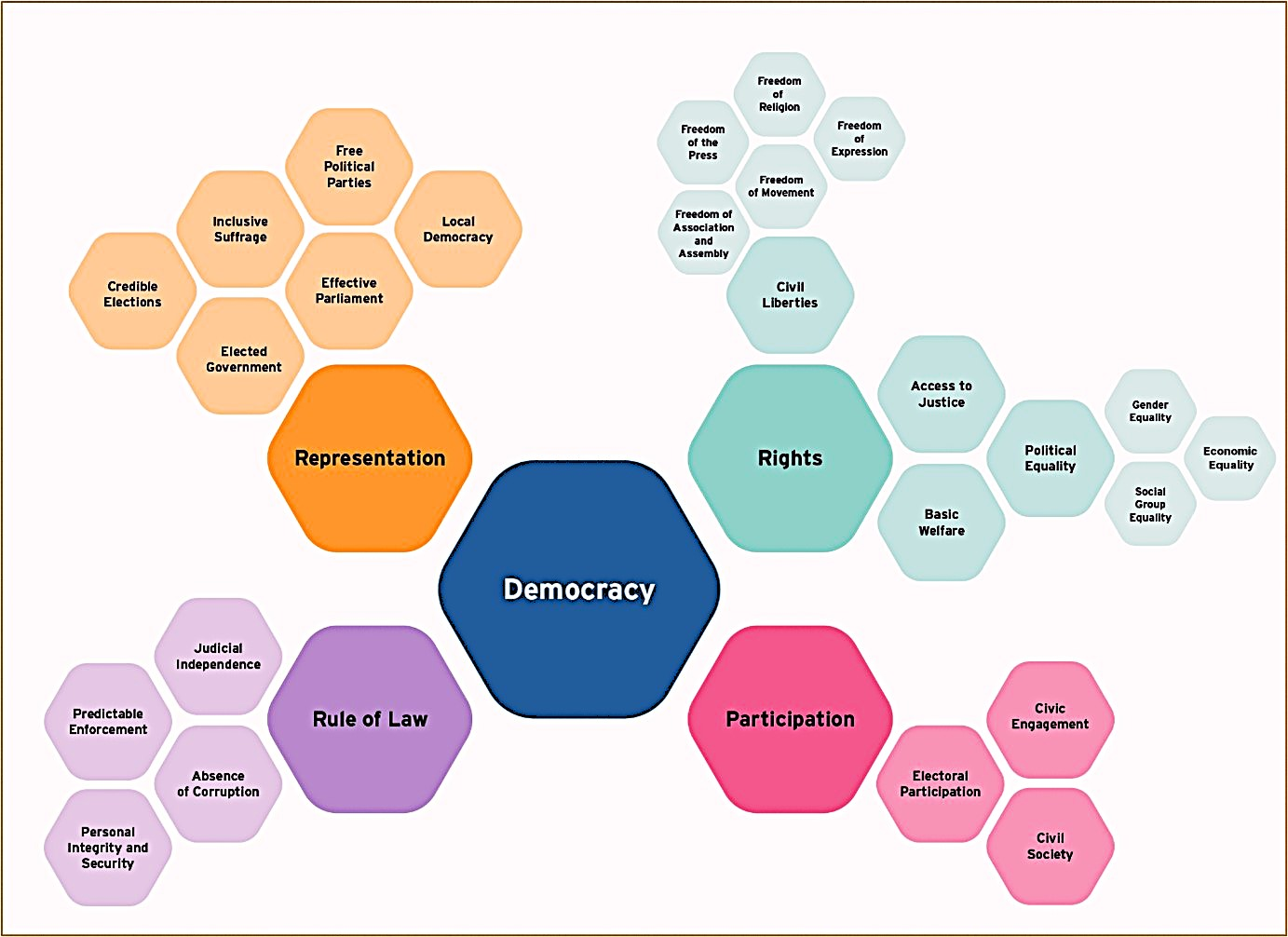

International IDEA adopts a broad conception of democracy as popular control over public decision making and decision makers, and equality of respect and voice between citizens in the exercise of that control.

To measure and compare trends in democracy, International IDEA has developed the Global State of Democracy Indices. These indices are organized across four main categories of democracy, which contain a total of 17 factors and eight sub-factors, measuring a total of 29 aspects of democracy (see Table 1).

| Categories | Factors | Definition |

|---|---|---|

| Representation | Credible elections | the extent to which elections for national, representative political office are free from irregularities |

| Inclusive suffrage | the extent to which adult citizens have equal and universal voting rights | |

| Free political parties | the extent to which political parties are free to form and campaign for political office | |

| Elected government | the extent to which national, representative government offices are filled through elections | |

| Effective parliament | the extent to which the legislature is capable of overseeing the executive | |

| Local democracy | the extent to which citizens can participate in free elections for influential local government | |

| Rights | Access to justice | the extent to which there is equal, fair access to justice |

| Basic welfare | the extent to which citizens can access fundamental services and resources, such as nutrition, social security, healthcare and education | |

| Civil liberties | the extent to which citizens enjoy the freedoms of expression, association, religion, movement, and personal integrity and security | |

| Political equality | the extent to which political equality between social groups and genders has been achieved | |

| Rule of law | Judicial independence | the extent to which the courts are not subject to undue influence, especially from the executive |

| Absence of corruption | the extent to which the executive, including public administration, does not abuse office for personal gain | |

| Predictable enforcement | the extent to which the executive and public officials enforce laws in a predictable manner | |

| Personal integrity and security | the extent to which bodily integrity is respected, and people are free from state and non-state political violence | |

| Participation | Civil society | the extent to which organized, voluntary, self-generating and autonomous social life is institutionally possible |

| Civic engagement | the extent to which people actively engage in civil society organizations and trade unions | |

| Electoral participation | the extent to which citizens vote in national legislative and (if applicable) executive elections |

Structure of the report

This report analyses the state of democracy in the Pacific region, drawing on International IDEA’s Global State of Democracy indices, as well as research and analysis from democracy specialists in the region. Because numbers do not tell the whole story, the report aims to present a holistic understanding of democracy by putting this abstract data into context.

The report is structured in two parts, each of which is intended to address a gap in our understanding of democracy in the region.

- Chapter 1: Exploring the data: examines the data compiled through the GSoD and reflects on its completeness in the light of research and knowledge compiled by researchers working in the region.

- Chapter 2: Conceptualizing Pacific democracy: considers what democracy means in the broader Pacific by examining six common features of the democratic context across the region: grassroots democracy, smallness, localized politics, cohabitation, political marginalization and democratic innovations. We also ask how global conceptions of democracy can be adapted to include Pacific lessons. This more conceptual exploration of the experience, meaning and aspiration of democracy in the region aims to incorporate factors that matter in the region but are left out of or minimized in global studies.

The report highlights broad trends in democratic performance across the region, and identifies continuing democratic successes and the challenges that face Pacific island countries. It concludes by presenting ways in which global indices of democracy might be adapted in the light of lessons from Pacific island countries and the region.

It is hoped that by demonstrating the variety of democratic practices in a region that does not fully feature in global assessments of democracy, the report will make a contribution to global conversations about democracy.

1.1. International IDEA’s Global State of Democracy Framework

Four core categories of democratic performance are at the heart of International IDEA’s assessment framework: Representation, Rights, Participation and the Rule of Law (see Figure 2). Associated with these four categories are key benchmarks, such as Credible Elections (under Representation), Civil Liberties (under Rights), Civic Engagement (under Participation) and Judicial Independence (under the Rule of Law). Some of these benchmarks have further indicators, such as Freedom of Expression (under Civil Liberties).

Based on this conceptual framework, International IDEA has characterized the global state of democracy as ‘complex, fluid and unequal’ (International IDEA 2023) and in a pattern of ‘decline’ (International IDEA 2024). This pattern of decline is counterbalanced, to some extent, by human rights institutions and civil society organizations, popular movements and independent investigative journalists interested in democratic accountability. On a regional basis, broad declines in democratic quality and continuing pressure on civic space in Asia and the Pacific are mitigated by respect for the rule of law and peaceful transitions of power following elections. The role of foreign powers in setting norms around governance and influencing democratic processes was also identified as a potential threat to democratic practice and standards in the Asia Pacific region.

1. The Pacific in the GSoD

Currently, the Global State of Democracy (GSoD) incorporates data from four countries in the Pacific region: Fiji, Papua New Guinea, Solomon Islands and Vanuatu. The global report only includes countries with more than 250,000 inhabitants while many Pacific countries—either independent, self-governing or with a status currently under negotiation—have smaller populations. For this reason, Cook Islands, Federated States of Micronesia, Nauru, Niue, Kiribati, Marshall Islands, Palau, Samoa, Tokelau, Tonga and Tuvalu are not included in these global or regional assessments of democracy.

This section analyses the data compiled through the GSoD in relation to Fiji, Papua New Guinea, Solomon Islands and Vanuatu by examining the ‘democratic performance webs’ created with GSoD data for each of these four countries. These webs are compiled by mapping each country’s ratings across the 17 different indicators of democratic performance from 0 to 1, where 1 represents ‘the highest democratic performance observed across all the country years’.1

For each country, a commentary on key democratic changes in the period between 2018 and 2023 is provided, followed by an analysis of the GSoD data and any potential gaps or misrepresentations in that data. Our intention is to provide some context for the data presented in the democratic performance webs and explain significant changes and trends in the period. The change is not the same for every country, however, and the analysis is therefore not necessarily of the same indicators. While our focus is on elections and political participation, the narrative for each country revolves around significant democratic events over the past five years.

In line with global trends, democratic standards are in a pattern of decline in the four countries, although the magnitude of decline varies. While quantitative measures capture the state of democracy across globally comparative indices, qualitative assessments explain local Pacific experiences of democratic backsliding (see Ratuva 2021). Moreover, in many parts of the Pacific, quantitative data collection is undermined either by capacity constraints or by elite capture. That is, there are limited resources and in-country know-how with which to monitor democratic standards and/or Pacific policymakers actively prevent certain data from being released (see Wood 2015).

Importantly, these are relatively young democracies—in terms of the age of some of the independent states and populations with very high proportions of young people (see Table 2 for key statistics on each of the four countries). There will therefore be cause for concern if these trends continue. Understanding the complexity of democratic decline is key to finding solutions that might remedy it.

| Fiji | Papua New Guinea | Solomon Islands | Vanuatu | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Population size (estimate) | 929,766 (2021) | 11.8 million (2024) | 758,000 (2024) | 326,740 (2022) |

| Youth population | 27.1% | 33.5% | 37.0% | 38.3% |

| Geography | 18,274 km2 322 islands | 452,860 km2 600 islands | 28,400 km2 1000 islands | 12,200 km2 80 islands |

| Major languages | English, Fijian and Hindi | Tok Pisin, Hiri Motu and English (+ 800 languages) | Pijin and English (+ 60 languages) | Bislama, English and French |

| Year of Independence | 1970 | 1975 | 1978 | 1980 |

| Form of government | Directly elected unicameral national parliament (55 members) | Directly elected unicameral national parliament (118 members) 22 provincial assemblies (including national capital district and the Autonomous Region of Bougainville) | Directly elected unicameral national parliament (50 members) Nine provincial assemblies | Directly elected unicameral national parliament (52 members) Six provincial assemblies |

| Human development classification | High | Medium | Medium | Medium |

Fiji

Between 2018 and 2023, Fiji emerged from a period of military administration to move towards a significant milestone of a peaceful, democratic transition of power in 2022. The November 2018 elections returned the ruling FijiFirst Party, led by former military commander Voreqe ‘Frank’ Bainimarama. These elections followed FijiFirst’s win in 2014, the first time the country had voted since a 2006 coup d’état led by Bainimarama, which followed previous coups in 1987 and 2000. This ‘democratic pause’ had been widely condemned by the international community (see Lal 2015), and Fiji’s membership of various organizations was suspended.

The 2018 elections were seen as credible by international observers. However, the FijiFirst government continued to be characterized by a restricted civil society space, constraints on opposition political activity and limits on freedom of speech and assembly (see Carnegie & Tarte 2018; Regan et al. 2024). Media executives and staff, for example, were charged with sedition, although later acquitted. Opposition members were suspended from parliament for relatively minor offences, leading to cases being heard by the Inter-Parliamentary Union’s Committee on the Human Rights of Parliamentarians (IPU 2019). Permits for marches and public demonstrations were regularly rejected by the government. Parliamentary processes were opaque and rushed, and legislation was often passed without meaningful consultation under Standing Order 51, ‘Motion for bill to proceed without delay’.

The 2022 elections were seen as a turning point in Fijian politics, resulting in a transfer of power from FijiFirst to a three-party coalition led by the former military commander and architect of the 1987 coups, Sitiveni Rabuka (Fraenkel 2024). The initial post-election period was strained, following an initial reluctance to concede on the part of Bainimarama, but the impasse was ultimately resolved peacefully. Bainimarama became Leader of the Opposition but was subsequently charged with obstructing police investigations into corruption, which led to a jail term and disqualification as an electoral candidate until 2032.

Indicators of democracy

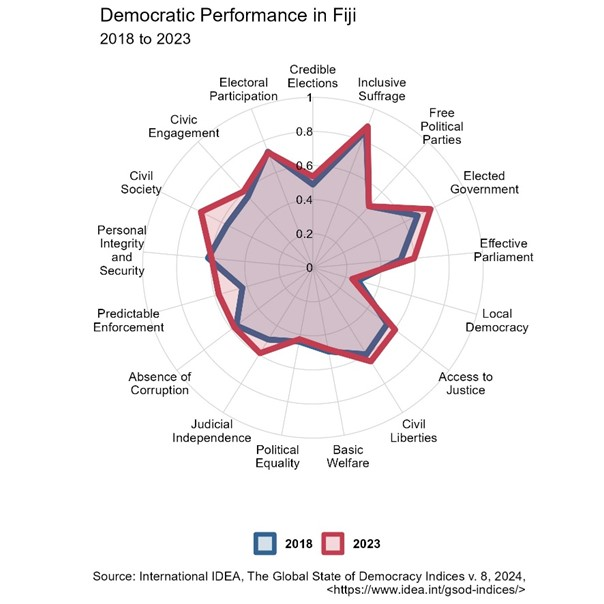

International IDEA’s assessment of democracy in Fiji (see Figure 3) shows that there appears to have been positive change on most indicators between 2018 (blue line) and 2023 (red line).

Specifically, the data suggest that improvements have been made with respect to the extent to which the legal and political context supports civil society organizations and activities (Civil Society), the extent to which the executive and public officials enforce laws in a predictable manner (Predictable Enforcement), the extent to which national government offices are filled through elections (Elected Government), the extent to which the legislature is capable of overseeing the executive (Effective Parliament) and the extent to which the judiciary is considered independent (Judicial Independence). All these improvements were statistically significant. Perceived improvements in the extent to which civil rights and liberties are respected (Civil Liberties) were not statistically significant.

The greatest margins of improvement were for Predictable Enforcement (from 0.43 to 0.57 out of a maximum score of 1) and Civil Society (from 0.56 to 0.73). Very little change was evident over this time period both in the highest score—for the extent to which adult citizens have equal and universal passive and active voting rights (Inclusive Suffrage, at 0.89 in 2023)—and in the lowest score (Local Democracy, at 0.24 in 2023). The Local Democracy indicator captures the extent to which local government is elected freely and fairly, and is empowered in relation to the central government. Free Political Parties, or the extent to which political parties are free to form and campaign for political office, was scored within the mid-range—and unchanged over the time period—at 0.49. Political Equality, or the extent to which political and social equality between social groups and genders is achieved, was also scored within the mid-range, but at the lower end, at 0.43 in 2023.

Contextualising democratic indicators

While the 2022 election demonstrated the possibility of democratic renewal in Fiji, it is important to contextualize a broader range of democratic practices before reaching the conclusion that Fiji was ‘more democratic’ in 2023 than in 2018. The transition of power following the 2022 election was somewhat chaotic, following Bainimarama’s initial refusal to concede, the involvement of the military and allegations of electoral interference (RNZ 2022). The ongoing role of the military in political life is still an unresolved issue. Prominent political leaders—notably Bainimarama and Rabuka—have histories of involvement in coups, which has resulted in a diminution of trust in their leadership and the institutions they lead. The transparency and accountability of parliamentary processes have not significantly improved since 2022 (see Baker & Palmieri 2024).

Declining voter turnout in Fiji (68.3 per cent in 2022, down from 84.6 per cent in 2014), coupled with the continued suspension of local government elections and the exclusion of Fijian diaspora from electoral processes, suggest that political participation is circumscribed. Municipal elections have not been held since 2006. The coalition government made a commitment to restore municipal councils but elections have been repeatedly deferred (see Baker & Kant 2023).

In some respects, Political Equality might be said to have worsened rather than remained constant. Women’s parliamentary representation declined following the 2022 elections, when only six women won seats (10.9 per cent) compared to ten in 2018 (19.6 per cent). Women’s representation is not guaranteed by policy or legislation, for example through temporary special measures, but is dependent on the overall vote share of those political parties which include women on their ticket. That women continue to find it difficult to win sufficient votes in their own right to secure a seat in parliament suggests that discriminatory and deeply held social norms around leadership hold significant sway at election time. These social norms are also evidenced in the treatment of Fijian women politicians on social media (see Kužel et al. 2022; NDI et al. 2021).

Under the Bainimarama government, a significant number of foreign judges were appointed to Fiji’s judiciary. Under the Constitution, non-citizen judges can serve only on three-year renewable contracts. This provides a powerful executive with a lever of influence over judges who wish to continue their appointments, which is a red flag for judicial independence. There was an increase in the scores for judicial independence in 2023, which might reflect an increase in the appointment of Fijian judges with guaranteed tenure until retirement.

Papua New Guinea

Elections have been regularly and strongly contested in Papua New Guinea, including in the period between 2018 and 2023. It is difficult, however, to describe these elections as fully democratic. In the case of many electorates, the process by which ballots are cast does not resemble a popular, democratic vote.

Following the 2017 election, which was ‘marred by widespread fraud and malpractice, including extensive vote rigging’ (Haley & Zubrinich 2018: 92), a nine-month state of emergency was declared in the Southern Highlands region, prompted by election-related riots.

Corruption allegations were dropped against Prime Minister Peter O’Neill in 2018, but he eventually resigned in 2019 in the lead-up to a proposed vote of no confidence. He was succeeded by his finance minister, James Marape. In 2021, the Supreme Court acquitted O’Neill of new corruption charges. He then asked the court to delay the 2022 elections, but the Supreme Court refused the request.

James Marape survived a vote of no confidence in 2020 and won the 2022 election, which was also described as plagued by irregularities and violence, with widespread fighting, displacement and destruction of property (Oppermann et al. 2025; Wood et al. 2023).

Despite the serious barriers to mounting a legal challenge, electoral disputes have become increasingly frequent in Papua New Guinea. Some challengers win their cases and are installed as members of parliament. More than 100 legal challenges were lodged with the courts in 2022 (Narokobi 2023). The courts also had some success in sentencing individuals for fraud. The prominent lawyer, Paul Paraka, was found guilty in 2023 of obtaining 162 million kina (USD 44 million) in government payments. The anti-corruption team that led the investigation into Paraka, Taskforce Sweep, was disbanded amid claims of government interference (see Walton & Hushang 2020), but was replaced by an Independent Commission against Corruption in 2023.

In late 2019, a referendum was held on the issue of independence for the Autonomous Region of Bougainville. In the non-binding referendum, 97.7 per cent of Bougainvilleans voted in favour of independence (see Regan et al. 2022). Post-referendum consultations have continued with no clear roadmap for resolution of the issue of self-determination for the region.

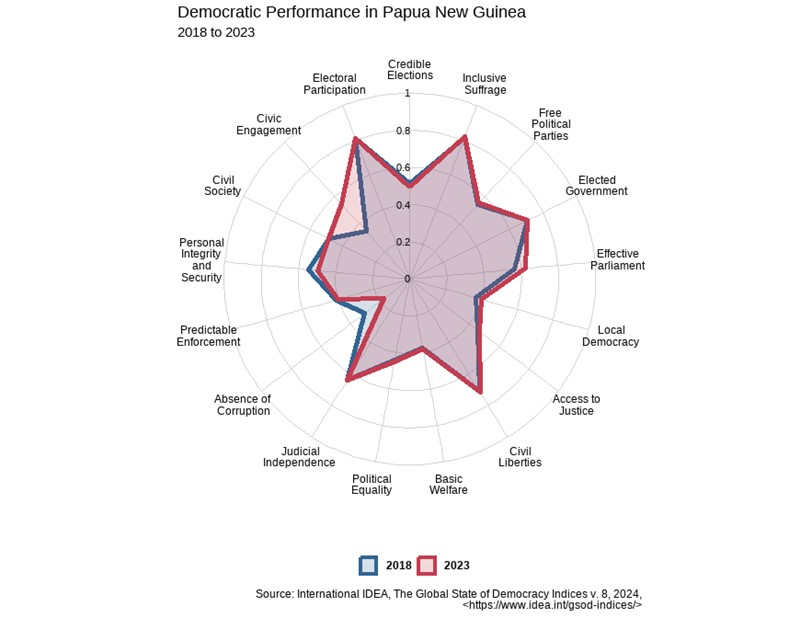

Indicators of democracy

The GSoD data suggest that there was little or no change across a number of democratic indicators between 2018 and 2023 (see Figure 4). With respect to Electoral Participation, Inclusive Suffrage, Free Political Parties, Elected Government, Access to Justice, Civil Liberties, Basic Welfare, Judicial Independence and Predictable Enforcement, democracy appeared static in Papua New Guinea. This is not to suggest, however, that the scores were all high. Concerningly, on Basic Welfare—or the extent to which the material and social supports of democracy such as nutrition, healthcare and education are available—Papua New Guinea scored 0.38 out of 1 in both 2018 and 2023.

Democratic standards appear to have significantly deteriorated in relation to the Absence of Corruption (0.3 in 2018 to 0.17 in 2023). The data suggest that executives and public administrators were more likely to abuse their office for personal gain in 2023 than they were in 2018. A perceived decline in the Personal Integrity and Security score from (0.55 in 2018 to 0.5 in 2023) was not statistically significant.

There was a statistically significant improvement in Freedom of Expression between 2018 and 2023. Perceived improvements in parliamentary effectiveness (0.58 in 2018 to 0.62 in 2023) and engagement in political and non-political associations (less than 0.4 in 2018, up to 0.55 in 2023) were not statistically significant. Papua New Guinea continued to score highly on Inclusive Suffrage and Electoral Participation (both just over 0.80 in 2018 and 2023).

Contextualising democratic indicators

These indicators do not paint a positive picture of the state of democracy in Papua New Guinea. In addition, large-scale observations of elections in 2017 (Haley & Zubrinich 2019) and 2022 (Oppermann et al. 2025), as well as of women’s participation in those elections (Haley and Baker 2023; Oppermann et al. 2025), raise a red flag for worsening standards. The basic infrastructure required to carry out an election continues to be inadequate. Electoral roll inaccuracies mean that it is increasingly difficult to use it for voter identification at polling time, affecting not only the credibility of the election but also the extent to which individuals are able to exercise their electoral franchise. Electoral malfeasance means that turnout rates are not meaningfully representative of participation in some areas. There is substantial ambiguity on electoral boundaries. Redistricting in 2022 resulted in inconsistent electorate maps. Some omitted densely populated areas, such as a provincial capital (Haley & Oppermann 2024). Moreover, careful inspection of polling schedules reveals that the country has been extensively redistricted outside of the legally mandated process (Oppermann et al. 2025).

A focus on national statistics can obscure significant subnational variations. Papua New Guinea's elections are extremely heterogeneous, leading to substantial inequality in polling conditions. The 2022 Papua New Guinea election observation report notes that voters were able to participate relatively freely in some areas, such as in the Autonomous Region of Bougainville, while in other areas ballots were divided in bulk between competing factions or pre-filled by officials and candidates’ agents before being handed to individuals (Oppermann et al. 2025). The observation also noted that polling boxes had been stolen or destroyed. These tactics are used by political and armed factions to manipulate election results. In such cases, it is less appropriate to speak of ‘election-related violence’ than to see elections as an element in a patchwork of complex civil conflicts over resources, power and control of local decision-making institutions. While electoral officials and the courts have tried to enforce electoral regulations, the volume of complaints is significant. Following the elections, 102 electoral petitions were filed, but the majority were dismissed due to non-compliance with electoral law (Narokobi 2023), which raises questions about the adequacy of current legislation.

This electoral environment has important implications for political organization and for parliament. Although there was more obvious involvement of political parties in the 2022 election, Papua New Guinea continues to have a weak party system (see Wood et al. 2023). Members of Parliament who wish to access resources for their home districts—generally the most substantial issue at play in electoral politics—must make alliances in parliament. Whether a Member of Parliament is ‘elected’ through the persuasion of voters or by other means is immaterial to these parliamentary alliances. This results in the absence of a parliamentary basis for electoral reform. In addition, it is all but impossible from the voters’ perspective to anticipate the kind of policy positions their representatives will adopt or deals they will make. There is thus a weak link between the selection of a Member of Parliament by voters and the formation of a government through a majority in parliament.

Political participation can be understood in broad terms across Papua New Guinea. Reported turnouts are a poor guide to participation in zones with severely disrupted electoral conditions, notably the Highlands. In 2022, the Papua New Guinea Election Commission received more ballots than registrations in 17 of the 96 open electorates. Elsewhere, turnout rates are less exaggerated but more representative of a ‘mobilization rate’ by which individuals are induced to vote for a particular faction rather than decide to cast a ballot for a candidate of their own choosing. A good deal of participation occurs at the local level. Measures of formal devolution and formal participation may be low but informal participation—in the sense of community level governance and conflict resolution—is stronger (Oppermann et al. 2025).

Solomon Islands

Geostrategic considerations influenced democratic quality in Solomon Islands between 2018 and 2023. In September 2019, Solomon Islands established official diplomatic relations with the People’s Republic of China, ending an era of diplomatic recognition of Taiwan (Aqorau 2021). This ‘switch’, instigated by then Prime Minister Manasseh Sogavare, was not unanimously endorsed by the national cabinet, resulting in the dismissal of several prominent members of the cabinet. Reverberations from this decision were also felt at the sub-national level, such as a vote of no confidence in Malaita Province premier Daniel Suidani in the provincial assembly in 2023. Suidani had been vocal in opposition to the switch, and foreign influence over politics and the economy, and there were allegations that the vote of no confidence was the result of corrupt payments made to members of the Malaita Provincial Assembly (Aumanu-Leong and Dziedzic, 2023).

In 2021, riots erupted in the country’s capital, Honiara, damaging large parts of its Chinatown and killing four people in fires (see Ride 2021). Peacekeeping forces from Australia, New Zealand and Papua New Guinea were brought in to quell the rioters. The riot catalysed a no-confidence motion in Prime Minister Sogavare, which he survived.

The parliament elected in 2019 included representatives from political parties—such as the Solomon Islands Democratic Party (SIDP), Kadere, and the Ownership, Unity and Responsibility (OUR) Party—as well as a number of independent Members of Parliament. OUR Party leader Sogavare fashioned a coalition government to secure control of parliament and his re-election as prime minister.

The election scheduled for 2023 was delayed by 12 months following passage of a constitutional amendment that extended the parliamentary term (see Baker 2023). The extension was attributed to the cost of running an election and hosting the Pacific Games in the same year, despite the financial support offered by Australia and other donors for the election. The offer was rejected by Sogavare on the grounds that it represented an attempt to interfere in the affairs of a sovereign nation.

Controls on state media were announced in the lead-up to the 2024 election, which required a government representative to vet news programmes for ‘lies and misinformation’. Some prominent civil society leaders were threatened with arrest and prosecution.

The 2024 election resulted in another coalition government, the Government for National Unity and Transformation (GNUT), this time built around the OUR Party, Kadere and People First, and the majority of independent candidates, while the Solomon Islands Democratic Party and the United Party remained in opposition. The GNUT coalition nominated Jeremiah Manele as their candidate for prime minister, and he won the parliamentary vote.

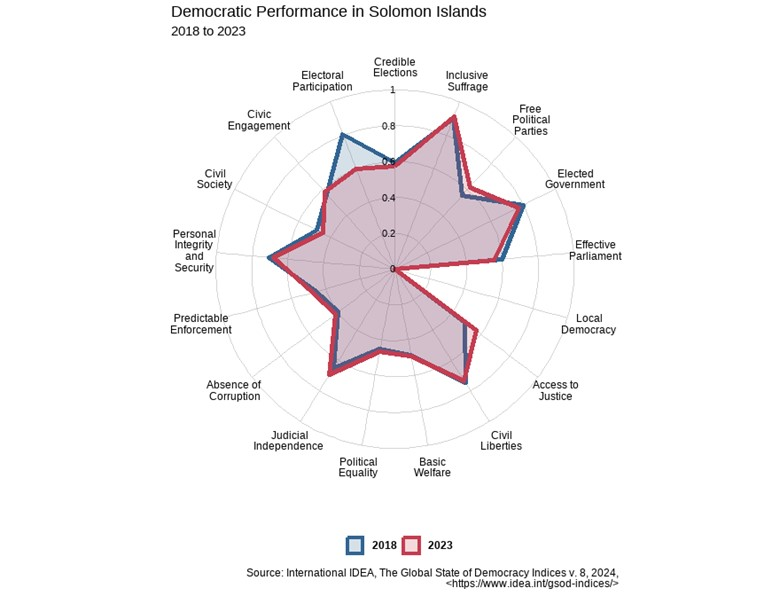

Indicators of democracy

As in Papua New Guinea, there was limited or no change in many of the GSoD indicators for Solomon Islands between 2018 and 2023 (see Figure 5). Scores varied considerably, however, across the 17 indicators. At the most extreme, Solomon Islands scored the lowest possible score (0) for Local Democracy in both 2018 and 2023, even though elections take place at the provincial level and these are broadly representative of ‘local concerns’. Little change was also noted in the Absence of Corruption (0.42), Political Equality (0.47), Basic Welfare (0.49) or Predictable Enforcement (0.48) over the time period.

Solomon Islands maintained stronger scores over the time period in terms of Personal Integrity and Security (0.68), Judicial Independence (0.69), Civil Liberties (0.73) and Inclusive Suffrage (0.91).

The data show that access to justice improved from 0.49 to 0.57 over the time period. Perceived increases in the extent to which political parties are free to form and campaign were not statistically significant (from 0.56 to 0.62).

Scores for electoral participation (or the turnout of the voting age population in national elections) worsened significantly from 0.8 in 2018 to 0.6 in 2023. Perceived marginal declines in the scores for elected government and effective parliament were not statistically significant.

Contextualizing democratic indicators

The extent to which democratic standards continue to decline—and the pace of that decline—is of concern in Solomon Islands. While the scores are already low, experiences in Solomon Islands over the time period—and, indeed, since 2023—suggest that the state of democracy is probably worse than is presented in some of the data. In part, this is because the findings of reports were released after GSoD data collection, which suggests that the processes by which democratic accountability is sought are themselves slow.

Poor scores on freedom—reportedly the worst in the Asia Pacific region (Freedom House 2023)—reflect the conflicts arising from dissent over the national government’s foreign policy and pandemic-related decisions, the deferral of elections in 2023 and anti-government protests followed by riots in 2021. In the time period studied, the Solomon Islands government threated to remove the charitable status of CSOs engaging in advocacy seen as anti-government, arrested silent protestors against the China switch, sanctioned police harassment of a pastor whose Facebook post was critical of the government and decided to ‘close’ Facebook—a decision it later reversed. The variety of means used to pressure freedom of speech and assembly may be underestimated in a score of 0.73 for civil liberties, particularly in a small community where government actions have a direct effect on an individual’s immediate circle of family and friends.

While the Absence of Corruption indicator remained relatively stable (at 0.42), including during the 28-month State of Emergency declared during the pandemic, a 2023 report by the Office of the Auditor General (OAG) on public spending during the Covid-19 years indicates a high rate of irregularity regarding procedures for procurement and the distribution of funds (OAG 2023). Specifically, the Auditor General:

identified transactions that did not comply with financial requirements in the tendering and awarding for contracts including not implementing the required competitive quotation/tendering process without an appropriate waiver, awarding contracts to businesses which did not have a valid or current business registration and failing to maintain adequate supporting documentation for transactions. (OAG 2023: 7)

The report, which was cited in the regional media in 2024 but is unlikely to have been captured in the GSoD data, came to the attention of the International Monetary Fund, which noted it would discuss the findings with the Solomon Islands authorities (see, for example, Pearl 2024).

The limited number of court cases progressed during the Covid-19 years (2020–2022) and the limited access to the formal, state justice system, notably for women (Ride 2025), raise question marks over the improved score for Access to Justice.

GSoD data indicate that Solomon Islands has scored zero for local democracy every year since 1997, having previously scored 0.45 between independence in 1978 and 1997. By any definition, local democracy suffered between 1997 and 1998. A review of local and provincial government in 1997—prompted by international pressure for structural adjustment of its bureaucracy and dire economy—resulted in the suspension of Area Councils (Allen et al. 2013: 10). Civil war broke out months later and local governments have not been elected since. Provincial assemblies are elected every four years, made up of ward-level representatives decided in local elections. Some places have retained the institutions of local government (Dinnen & Haley 2012). As noted in relation to Papua New Guinea, the variation that exists at the local level in Solomon Islands is difficult to capture in national indices.

Vanuatu

Frequent political turnover instigated by no-confidence motions and floor crossings has been a defining characteristic of parliamentary democracy in Vanuatu. Contestation over changes in government is often resolved through the courts. Prime Minister Charlot Salwai survived several no confidence motions in parliament but he was convicted of perjury in 2020 for making false statements in court in relation to one of these votes. A year later, Salwai would be pardoned by President Tallis alongside two other former prime ministers—Joe Natuman and Serge Vohor—and again become eligible to contest elections. When 19 members of parliament, including the then Prime Minister, Bob Loughman, boycotted parliament in June 2021, the Speaker, Gracia Shadrack, ruled that they had effectively resigned by vacating their seats. While the Supreme Court initially upheld the Speaker’s decision, the Members of Parliament were eventually reinstated on appeal.

A snap election in 2022 elected Ishmael Kalsakau of the Union of Moderate Parties. There was further turmoil in 2023 when the government’s leadership changed hands three times. Prime Ministers Kalsakau and Sato Kilman each lost parliament’s confidence in quick succession, resulting in the return of Charlot Salwai in October 2023. Further leadership change was avoided two months later when a renegotiated coalition government was formed.

This spate of government turnover prompted a renewed effort to introduce legislation on political integrity (see Naupa et al. 2023). Constitutional reform on this issue had been touted previously, most recently in 2018, but failed to achieve a parliamentary consensus. In 2024, Vanuatu held its first ever referendum to insert provisions into the Constitution to enhance political stability, through an anti-party-hopping amendment and the introduction of a requirement that Members of Parliament have a party affiliation, essentially banning independent Members of Parliament. Both were approved through the referendum process.

Women’s representation has historically been low in Vanuatu. In the 2022 general election, just one woman (Gloria Julia King) was elected to the 52-seat parliament. Outside the parliamentary context, the first ni-Vanuatu woman Supreme Court justice, Viran Molisa Trief, was appointed in July 2019.

Perceptions of threats to freedom of speech followed reports in 2018 that China intended to build a military base in the second most populated province, Sanma. The traditional media environment in Vanuatu is constrained by funding and capacity limitations, and at times by tensions with the government of the day. A work permit renewal request for journalist Dan McGarry was denied in 2019 following his reporting on Chinese activity in the country, although the Supreme Court later revoked a travel ban that had prevented him from returning to Vanuatu.

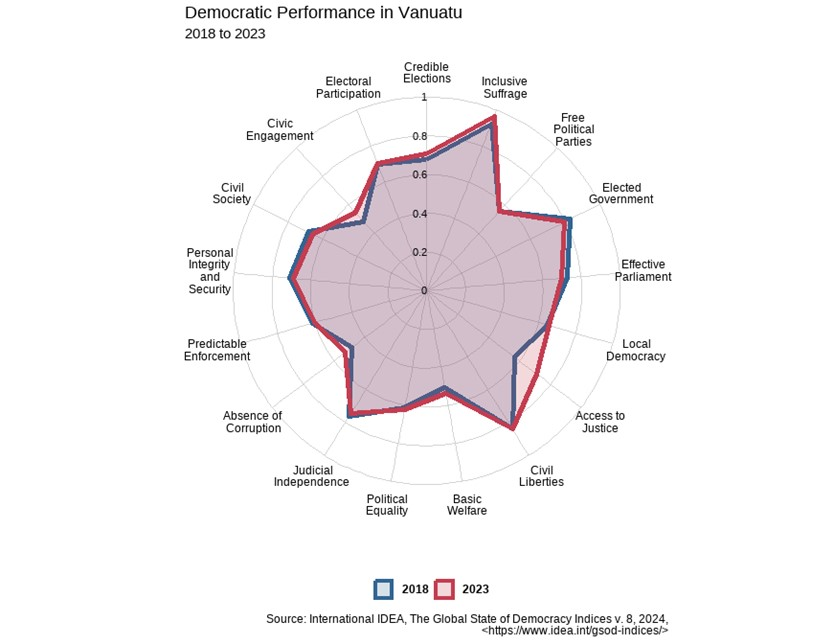

Indicators of democracy

Vanuatu scores higher on many of the democracy indices reported in the GSoD than the other countries analysed in the region (see Figure 6). Inclusive Suffrage, for example, while scored highly in Fiji, Papua New Guinea and Solomon Islands, is almost at 1 in Vanuatu. Local Democracy scores 0.66, compared with 0 in Solomon Islands, 0.24 in Fiji and 0.4 in Papua New Guinea. In keeping with the trend evident in the region, however, there was little change in most scores between 2018 and 2023. The GSoD data for Vanuatu suggests consistently strong Judicial Independence (0.75 in 2023) and Civil Liberties (0.84).

Statistically significant positive change was evident in relation to Access to Justice (from 0.57 in 2018 to 0.71 in 2023). A perceived, but not statistically significant, decline was evident in relation to scores on Elected Government (0.83 in 2018 down to 0.8 in 2023), Effective Parliament, Personal Integrity and Security, and Civil Society. The extent to which political parties were able to form freely does not seem to have improved over the time period.

Contextualizing democratic indicators

The GSoD data paint a relatively positive picture for Vanuatu, although in reality high levels of political instability have been having an impact on the country’s economy and level of service delivery for some time. The impact of Covid-19 on the country’s primary source of income—tourism—continues to be devastating (Connell & Taulealo 2021), leading to the collapse of the national airline, Air Vanuatu, in 2024. While still not a high score, Basic Welfare is effectively provided by development programmes that support local actors working with a range of community organizations, including faith-based organizations (Silas et al. 2022). This measure, which is based on outcomes, might not therefore be a strong indicator of state capacity.

While Vanuatu has had frequent elections—and these are managed relatively seamlessly with the support of international actors (UNDP 2021)—political instability degrades the efficiency and effectiveness of both government and the parliament. Indeed, it is clear that without judicial intervention, politicians in Vanuatu would not be able to resolve the many conflicts of interest that erupt in parliament (Forsyth 2015). It remains an open question whether the constitutional amendments passed in 2024 will result in fewer parliamentarians crossing the floor.

It should be noted that there is a high level of support for democracy in Vanuatu. In the Pacific Attitudes Survey, 76 per cent of respondents in Vanuatu agreed that ‘democracy is always preferable to any other kind of government’ and 84 per cent expressed satisfaction with the way democracy worked in practice (Mudaliar et al. 2024). Nonetheless, there is also clearly limited political efficacy: 85 per cent of respondents agreed with the statement that ‘politics seems so complicated that a person like me can’t really understand what is going on’ (Mudaliar et al. 2024).

The almost perfect score for Inclusive Suffrage does not capture deeply held conventions in the country that normalize men’s influence over women’s votes, and the perception among many voters that their vote is not secret (Toa et al. 2024). Instances of voter bribery are increasing, leading specific individuals—often party workers—to exert greater control over their community’s votes by offering food and other incentives. While this is covered in indices around corruption, there may be a need for suffrage and equality indicators to monitor the extent to which all voters feel they have full agency when casting a vote.

Chapter 1 contextualized the GSoD data that are available for the Pacific. However, the four countries discussed do not constitute a full or even representative picture of democracy in the region. This section examines Pacific democracy more broadly to ask how democracy in the Pacific might be understood.

A Pacific lens on democracy should account for how local and Indigenous processes of representation and leadership are reflected in participatory democracy, which includes elected and nominated leadership in traditional government systems, civil society, women’s and youth networks, and subnational forms of government. It should also consider how smallness impacts political dynamics, as well as cultural diversity across islands and Indigenous practices, which may or may not have been coded into formal parliamentary systems adopted from colonial powers in the histories shaping national Pacific governments. Finally, it should engage with the enduring political marginalization of some societal groups, while also taking into account the democratic innovations and experimentation that thrive in Pacific contexts.

Given the complexity of democratic practice in the Pacific, and the diversity of democratic experience as practiced across the region, we do not aim to present a comprehensive account of Pacific experiences of democracy. Instead, we examine in detail six dynamics that are common features of democratic contexts across the region: grassroots democracy, smallness, localized politics, cohabitation, political marginalization and democratic innovation.

2.1. Grassroots democracy

A standard framing of politics centres around engagement with state institutions in measurable ways—for example, voting in an election. While important, this framework is inadequate for capturing the fullness and vibrancy of political participation in the Pacific. It can also be misleading: in Papua New Guinea, for example, the practices for capturing polling stations and mandated group voting create turnout figures that do not relate to the number of citizens who handled ballot papers. In some areas, the number of ballots exceeds the number of registered or enrolled voters, creating implausible turnout figures of more than 100 per cent (see Oppermann et al. 2025). Even where citizens have custody of their own ballot papers, norms of bloc voting can limit the ability to vote freely, in a dynamic that is highly gendered (see Haley & Baker 2023; Toa et al. 2024).

Adopting a broad lens can show a fuller picture of how Pacific Islanders engage politically (see Baker & Barbara 2020). Many forms of participatory democratic practices in the Pacific are not captured in existing frameworks, due to the myriad ways in which they occur outside national state structures, as well as the diversity of political systems. How ordinary citizens see and practice politics in their everyday lives, which can be termed grassroots democracy, often nurtures networks and practices that can influence and inform engagement with the state through formal processes.

An alternative approach to evaluating political participation that looks beyond formal, state-level institutions is difficult to incorporate into datasets (see Baker & Barbara 2020). Many measurable indicators are underpinned by narrow conceptualizations of what constitutes political participation. Existing research on Pacific politics, however, can provide some insight into how these structures contribute to democratic resilience.

One element of political participation that might be underrepresented is the formation of participatory and democratic practices in local political units. In the Pacific, local leadership can involve representing kinship groups (e.g. the chief of a clan) or local areas (e.g. leaders in a particular village). These roles are typically bestowed through some form of ceremony that is preceded by an agreed process, which can include dialogue, consultations, mediations and informal or formal elections.

Such leadership processes can perpetuate social norms that favour older male representatives, reinforcing national-level dynamics and inequities in representation (see Baker 2018; Tuuau & Howard 2019; Palmieri & Zetlin 2020). Nonetheless, within local and village governance structures, there are also opportunities for political participation and leadership through peer networks—for example, women’s and youth organizations. These can offer avenues for engagement in decision making in spaces where there are fewer barriers to entry for participants, and in some cases can constitute important, but perhaps under recognized, pillars of local governance (see Motusaga 2016).

These leadership structures may or may not be incorporated into state processes. In Samoa, for example, traditional village-level governance structures have been partially codified into the state system through the Constitution and Village Fono Act (see Boodoosingh and Schoeffel 2018). The Tokelau political system allows for village-level representation in the General Fono (parliament), and there is considerable local discretion as to how village representatives are selected (Kalolo 2016).

Interest-based groups, such as environmental organizations, women’s civil society groups, and labour and student unions can also be important sites of democratic practices at the local or national level (see Palmieri et al. 2023). Particularly for members of communities that are underrepresented in formal politics, engaging in politics through interest groups can create space for issues-based advocacy and social change. The Young Women’s Parliamentary Group in Solomon Islands, for example, engaged in cervical cancer awareness campaigning by deliberately framing the controversial topic as a community issue rather than a political issue (Spark & Corbett 2018). While this was successful, the space for marginalized groups is being constrained in some parts of the Pacific, as in Solomon Islands (see Chapter 1), and in Vanuatu where there have been moves to institute a national policy that would ban LGTQIA+ advocacy (see RNZ Pacific 2024).

2.2. Size and scale

While recognizing the contested nature of the term (see Hau’ofa 1994), most of the democracies in the Pacific Islands region can be described as ‘small’. The region is home to the world’s highest concentration of micro-states. As noted in Chapter 1, this has obvious implications, such as their relative absence from global datasets. However, the relatively small size and scale of Pacific Island nations also has a tangible impact on democracy in terms of participation, representation and the rule of law.

The academic literature on the politics of small states often claims that small states are more likely to be democratic (see Anckar 2002; Hadenius 1992; Srebrnik 2004). The Pacific region is often held up as proof of this theory (see Corbett 2015a), with only a few exceptions. However, democracy is qualitatively different in small states. Hyper-personalization, for example, creates distinct political practices (Corbett & Veenendaal 2018).

The size of political units coupled with the relative absence of strong party systems creates political systems defined by hyper-personalization, in which there are strong connections between the leaders in political office and their family, kinship and community networks (Corbett 2015a). Personalization can mean that it is often hard to foster dissent and practice political resistance in Pacific societies, which limits the scope for grassroots democracy as described above.

The hyper-personalization of politics leads to two key trends in Pacific politics: extreme political fluidity and elite power consolidation. While seemingly at opposite ends of the political scale, some Pacific states fluctuate between these two extremes. Personalization can lead to political fluidity and instability, as Members of Parliament throw their support behind the person who they think will end up with the most power. This is evident in frequent government reshuffles, real and threatened votes of no confidence, and short-lived prime ministerships in countries such as Papua New Guinea, Solomon Islands and Vanuatu. In Vanuatu in 2015, 15 Members of Parliament—almost one-third of the country’s parliamentarians—were convicted of bribery, in charges related to payments made for arranging a vote of no confidence (see Forsyth & Batley 2016). In countries such as Papua New Guinea there is a clear trend towards fewer parliamentary sitting days as part of government efforts to evade votes of no confidence (Kabuni et al. 2022), which limits legislative capacity and the oversight function of parliament.

There are also serious implications in cases of elite power consolidation. In small states, limited human resources mean that government officials are often called on to perform multiple roles (Dziedzic 2025). The accumulation of roles in the one office, in combination with the personalization of politics, can have consequences for the rule of law. This can result in a blurring of the separation of powers, heads of the executive with unchecked powers (as in Nauru, see Firth 2016), clientelism and patronage, and one-party political dominance (as in Samoa, see Lati 2013). Nauru’s experience provides a cautionary example, where the president usually commands the support of parliament and the cabinet. Individual presidents have used this position to remove judges from office and interfere in cases before the courts (see, for example, the case of the Nauru 19: Ewart 2018). Some governments have restricted various media outlets and foreign journalists, and blocked access to Facebook, while opposition Members of Parliament have been suspended from parliament indefinitely, compromising nearly all the mechanisms for accountability (Firth 2016; Eames 2014).

The personalization of politics can also be perceived as ‘a blessing’, as it means that people in leadership positions are closer to the community, which can enhance representation, participation and accountability (Corbett & Veenendaal, 2019). Pacific Islands States have developed innovative institutional mechanisms for accountability. One example is Leadership Codes, which set out principles of leadership and standards of behaviour, and are enforced by independent commissions, such as an Ombudsman or a specific Leadership Commission. Examples arise in Kiribati, Nauru, Papua New Guinea, Solomon Islands, Tuvalu and Vanuatu, and codes are being developed in Fiji, Marshall Islands and Tonga. In a reflection of cohabitation (discussed below), some Leadership Codes apply to traditional leaders, for example in Tuvalu.

Judicial independence is another key element of the rule of law that takes on particular features in Pacific states that might be seen as departing from international standards. A common concern relates to impartiality. Judges and other independent office holders often work in small communities where they have family and community connections. To avoid the strict application of rules against bias, which would effectively leave communities without access to justice, several Pacific states have developed their own guidelines for judicial conduct to meet the practical realities of judging in small states. The use of foreign judges and other independent office holders drawn from outside the state is sometimes justified as a way to ensure impartiality. However, aspects of this practice can impinge on judicial independence in other ways, the appointment of foreign judges on short, renewable contracts being a prime example (Dziedzic 2021).

2.3. Localized politics

Politics tends to be localized in nature in the region. Voter choice is primarily dictated by local concerns and personalized relationships with representatives (see Corbett 2015b; Wood 2013). Webster (2022: 30) refers to ‘service delivery syndrome’ in Papua New Guinea, where voters expect politicians to primarily deliver local services over national development, a phenomenon also observed in other Pacific countries (see for example Mudaliar et al. 2024; Wiltshire et al. 2019). Constituency development funds, which are discretionary pools of money for politicians to spend on their electorates, have become a notable proportion of national budgets, particularly in Papua New Guinea and Solomon Islands. This has entrenched this dynamic (see Webster 2022; Futaiasi 2022).

Where they exist, political parties are perceived as weakly institutionalized by standard metrics (see Corbett 2015b; Rich 2008). Party affiliation often has little or no impact on the election process, and only becomes important in the ‘election after the election’—the selection of the prime minister and cabinet. In such contexts, it appears that the ability of parties and other centralized institutions to drive norm change in terms of political leadership is limited.

Political parties in the region are loosely structured, with little in the way of an ideological base, and often primarily function as vehicles for the leadership aspirations of individual politicians, rather than as a means of collective representation (see Rich 2008). These dynamics persist despite attempts to institutionalize party systems through legislative measures and electoral reform. So-called ‘anti-party hopping’ laws have been instituted in a range of countries, such as Samoa, Solomon Islands and Papua New Guinea, and Vanuatu held a referendum to constitutionally enact its own anti-party hopping measures in May 2024.

Moving beyond the western framework of party organization can provide a better picture of how parties in the Pacific operate as instruments of representation. Parties in the region are often characterized as disorderly and chaotic, but in fact serve distinct representative functions and purposes. Each operates in accordance with the internal logic of its political system. Ideologically flexible positioning, for example, is important for parties in contexts where voting is hyper-personalized and candidates need to tailor campaigning to their own particular context (see Corbett 2015b). Many Pacific countries have single-member constituencies, which favour this type of decentralized campaigning. Even in different contexts, such as in Fiji, where a proportional representation electoral system favours larger parties, the open list element means that parties have no control over the choice of candidates elected, and in practice campaigning often mimics single-member districts with candidates targeting particular geographic areas (see Nakagawa 2018).

Flexibility, in ideology and in personnel, is a feature rather than a bug of Pacific party organization. This flexibility serves a key function in terms of the leadership aspirations of party leaders. This also means that even political parties that are ostensibly well-institutionalized and nationally popular rarely survive the end of the political career of their leader. The recent demise of FijiFirst is a case in point. Where they do survive, it is often because they have been flexible enough to serve the leadership aspirations of another political actor, regardless of their approach to politics.

What does this mean for representation? Pacific parties, because of this by-design flexibility, have no electoral incentive to descriptively represent a broad range of societal groups in their candidate lists, because candidate selection is effectively decentralized to local communities. Equally, they have no electoral incentive to substantively represent the interests of particular groups, because they do not rely on an ideological voter base. Political systems across the Pacific are oriented towards older male elite interests and despite some individual successes by prominent women in disrupting this, on the whole they constrain opportunities for more diverse parliamentary representation. As noted above, however, parties and parliaments are just one means of political representation. By broadening our definition, it is possible to find underacknowledged pathways. The proportion of women as senior leaders in the public services, for instance, far outweighs their parliamentary representation in many Pacific states (see Chan Tung 2013). These positions can provide substantial influence over policy direction, all the more so in states where the legislative and oversight functions of parliament are weak.

2.4. Cohabitation

Pacific democracies operate within distinct frameworks, each of which incorporates combinations of customary, religious and modern/western elements of political governance with varying degrees of formalization. This fusion of disparate elements has been given different labels, such as ‘pluralism’ or ‘hybrid governance’. We use the term ‘cohabitation’ to indicate that instead of ‘hybridizing’ to form a distinct political order, customary, religious and non-traditional political norms and practices coexist—sometimes harmoniously and sometimes in conflict (see Viegas & Feijó 2017; Baker et al. 2024).

One aspect of democracy in which cohabitation can be seen is in the principle of the secret ballot. Established as an international norm of democracy, this principle is relatively weakly institutionalized in many Pacific countries. This is despite a range of administrative efforts to strengthen the secret ballot, such as the introduction of gender-segregated polling in Papua New Guinea (Haley and Zubrinich 2018), and batch counting processes in Solomon Islands (Wiltshire et al. 2019). Nonetheless, ideas around communal voting are pervasive in the Pacific: voting is not seen as an individual right but as an obligation undertaken on behalf of the community. This gives rise to common practices like bloc voting (see Haley and Zubrinich 2018; Oppermann et al. 2025; Webster 2022). While these are widely accepted practices that in many cases are seen as more culturally appropriate than individualized voting, they have implications for electoral integrity as they can increase the chances of voter intimidation and post-election retaliation, risks that are higher for women and other marginalized groups (see Haley & Baker 2023; Toa et al. 2024).

Another democratic principle affected by cohabitation is ‘one person one vote’. In Samoa, for example, traditional place-based political divisions have historically been prioritized over principles of equal constituency size when drawing electoral boundaries—a practice that creates unequal vote weightings but aligns with customary logic on spatial political affiliation. This logic of cohabitation, however, has been disrupted by changes to the Electoral Act in 2019 (see Dziedzic 2022).

In global discourse, recognition of customary norms sometimes raises concerns about the protection of human rights. There is a continuing debate in many countries in the region about the relationship between human rights and Indigenous customary values. This is sometimes framed as a contest between the human rights of the individual and the collective rights of the people to cultural or traditional values. This tension was at the heart of controversial court decisions in Tuvalu concerning whether island authorities could ban the establishment of new churches, which in turn motivated constitutional amendments to give greater precedence to custom over rights (Dziedzic 2024). An alternative view of the relationship is provided by Samoa’s Ombudsman, Maiava Iulai Toma, who has stated that ‘Human rights are not merely foreign ideals as many wish to see them, but they have roots within Samoan culture also … [T]he weaving together of Fa’asamoa and human rights principles will make a stronger and more harmonious society’ (Office of the Ombudsman and National Human Rights Institute 2015: 3). Yet another view suggests that human rights are to be seen through Indigenous eyes, where rights are not to be balanced against custom and tradition, as the duties, responsibilities and obligations that are grounded in Indigenous worldviews are also rights (Apinelu 2022). These debates are not easily resolved in theory or in practice. When human rights standards are themselves so complex, assessing compliance, including for the purposes of measuring democratic performance, is particularly difficult.

Measurements of human rights often take into account their enforcement by accessible and independent courts. In many Pacific states, people can access justice through both formal and informal systems of justice. There is increasing recognition that justice administered at the community level, based on customary law, is a critical part of the wider justice system. Often, it is more accessible to people than formal courts (see Forsyth 2009). These systems do not always cohabitate harmoniously, however, and it has been noted that access to justice in cases of gender-based violence, for instance, can be complicated by norms that favour village court processes (see Hemer 2018).

2.5. Political marginalization

Throughout the Pacific, as in much of the world, politics is dominated by a certain subset of the population, usually older men with status in their community. In practice, this has led to significant underrepresentation of other societal groups, most notably women. Other historically marginalized groups—including young people, diverse SOGIESC communities,2 and ethnic minorities—have also struggled to make significant gains in terms of representation. Electoral rules and electoral administration capacity issues also tend to limit the political engagement of citizens who have migrated from their home communities, either internationally or domestically. In a region with high rates of migration, and which is facing significant climate-related displacement, this is an important enfranchisement issue.

At less than eight per cent, women’s representation in Pacific parliaments is the lowest of any region in the world (IPU 2024). This has been a persistent pattern, and any gains made in one parliament are often offset by setbacks in others. In elections in 2024, for example, women’s representation increased in Kiribati but declined in Tuvalu and Solomon Islands. In Palau, the incumbent woman Vice President, J. Uduch Sengebau Senior, lost her bid for re-election in November 2024.

It is important to look beyond the raw numbers of women elected to analyse trends in vote share for women candidates and the number of women contesting. Even here, however, we do not see any clear positive trends. Across the region, women are less likely than men to stand for election, and less likely to win when they do stand (see Barbara & Baker 2016). Some interventions, however, particularly bespoke programmes of mentoring and raising community awareness, do show some signs of success (see Haley 2024).

While women as a group have been underrepresented at all levels of formal politics in the region, there are notable individual success stories. As of December 2024, there were two women heads of government in the Pacific Islands region: Hilda Heine in Marshall Islands and Fiame Naomi Mata’afa in Samoa. The experiences of these women highlight the complex intersections of gender, rank, class and background that facilitate access to politics in the region (see Spark, Cox and Corbett 2019).

In Tonga, government efforts to sign the United Nations Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination against Women (CEDAW) were stymied in 2015, following concerted protests led by religious organizations and a move by the Privy Council to declare the proposal unconstitutional (see Lee 2017). The widespread opposition to CEDAW in Tonga, along with a similar backlash to gender equality proposals elsewhere in the Pacific (see Baker 2019), suggest that a certain resistance to international norms on gender equality is pervasive throughout the region.