The Absent Voters of Sri Lanka

Challenges and Prospects for the Enfranchisement of Migrants

Introduction

Migration in Sri Lanka has seen significant growth in the past two decades, with approximately 1.7 million citizens working abroad and nearly 3 million living overseas. Despite this demographic shift, Sri Lanka’s electoral system has struggled to adapt, continuing to leave its absent voters disenfranchised.

The challenge of enfranchising migrants has been recognized by several parliamentary and presidential electoral reform committees and civil society, yet viable solutions have been elusive. Attempts to guarantee the right to suffrage to Sri Lanka’s absent voters—including recommendations from international conventions and human rights bodies—have fallen short. Key challenges persist and include the need for legal reform, security concerns, financial constraints and the lack of a broad political consensus on viable electoral reform.

This case study highlights how prospects for the enfranchisement of Sri Lanka’s migrants would require a staged approach. The first step would entail exploring what viable absentee voting methods exist among those successfully employed by other international jurisdictions, and then assessing the various challenges their introduction in Sri Lanka would present. After garnering the required political support, the last step would be to choose, design and finally implement the most suitable absentee voting method(s) for Sri Lanka’s unique context.

1. Migration in Sri Lanka: Background and characteristics

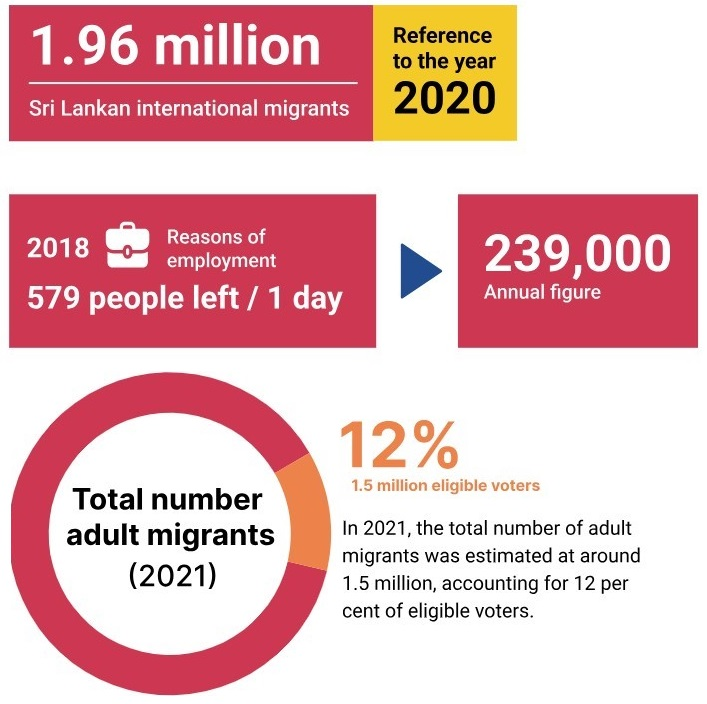

In the past two decades, Sri Lanka has seen a tenfold increase in its migrant numbers. The most recent estimates released by the United Nations indicate that, as of 2020, about 1.96 million Sri Lankans were working abroad (UN DESA 2020). However, other sources suggest that almost 3 million Sri Lankans are living overseas, which corresponds to one in eight persons of the population (OOSLA 2023). This represents an outflow of valuable human capital that could otherwise be deployed to further economic growth and development in Sri Lanka.

A study on the enfranchisement of Sri Lanka’s migrants published in the early 2000s attested that, in the period 1985–2000, approximately 5 per cent of the Sri Lankan labour force was based abroad (Sriskandarajah 2002: 269; Jayatilaka 2020). Years of conflict led to the significant displacement and migration within the Tamil community (Anandakugan 2020). Referred to as ‘the Tamil Diaspora’, many of these individuals left the country as refugees and asylum seekers to settle permanently overseas (Anandakugan 2020). Their reasons were economic as well as political, but also for personal security.

Furthermore, data from the Sri Lanka Bureau of Foreign Employment (SLBFE) shows that, on average, in 2018 almost 600 people1 a day left the country for reasons of employment, amounting to an annual figure of over 200,000 emigrants (SLBFE 2022).

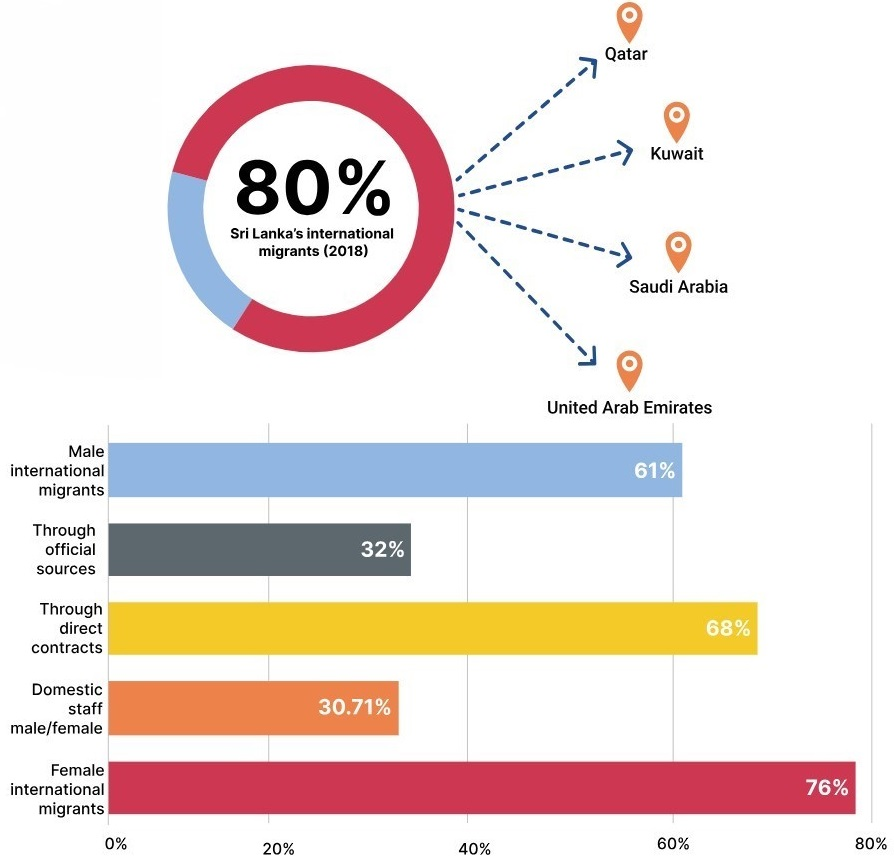

According to statistics released in 2022 by the SLBFE, 60 per cent of Sri Lanka’s international migrants were males and 40 per cent females. In 2018, 32 per cent of them migrated through official channels for employment and 68 per cent via direct contacts. Some 31 per cent of all migrants and 76 per cent of female migrants worked as domestic staff. As a result, both domestic workers and women who migrate through direct means shift the gender balance in favour of women. In 2022, skilled migrants account for 32 per cent of the total (SLBFE 2022). Kuwait, Qatar, Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates are the top destinations for nearly 80 per cent of Sri Lankan international migrants (SLBFE 2022). These figures highlight a significant challenge for Sri Lanka’s inclusive democracy. Given their numbers, enfranchising migrants could potentially influence domestic election outcomes.

It is noteworthy that remittances were the largest foreign exchange earner for Sri Lanka in 2018, at USD 7.1 billion (Central Bank of Sri Lanka 2019). This demonstrates that migration is a key pillar of the national economy. At the start of the Covid-19 pandemic, remittances fell from USD 6.7 billion in 2019 to around USD 5.23 billion in 2020 (Weeraratne 2020).

A considerable number of internal migrants also leave the villages and towns of their birth or habitual residence to settle in other towns or cities around the country for education and employment purposes (Perera 2020). Many maintain close ties with their places of origin and regularly return home to meet with family, to celebrate festivals and to vote. This pattern underscores the cultural and familial bonds that persist despite relocation for education or employment. Sri Lanka is a small country that is relatively well served by public transport, so travel issues are not insurmountable.

A significant number of people are employed in free-trade zones, or special economic zones, mainly in the garment manufacturing sector, and they fall into a grey area. They have lived away from home for several years but have not registered their place of occupation as their place of residence and are generally unable to get leave to travel home to vote. Many have ceased to register to vote in their hometowns (Sri Lanka Brief 2024). During the Covid-19 pandemic, they were severely disadvantaged, as they were not considered eligible for samurdhi benefits (grants of LKR 5,000 [USD 17] provided to low-income families), as they were not registered at their place of work (UNICEF 2020).

Many Sri Lankans were also internally displaced following the 30-year civil war, and many of them have not returned to their original places of residence. Some migrants have struggled to reclaim land and homes while others have created lives for themselves elsewhere in the country (Mittal and Fraser 2016).

2. Drivers of migration within and outside Sri Lanka

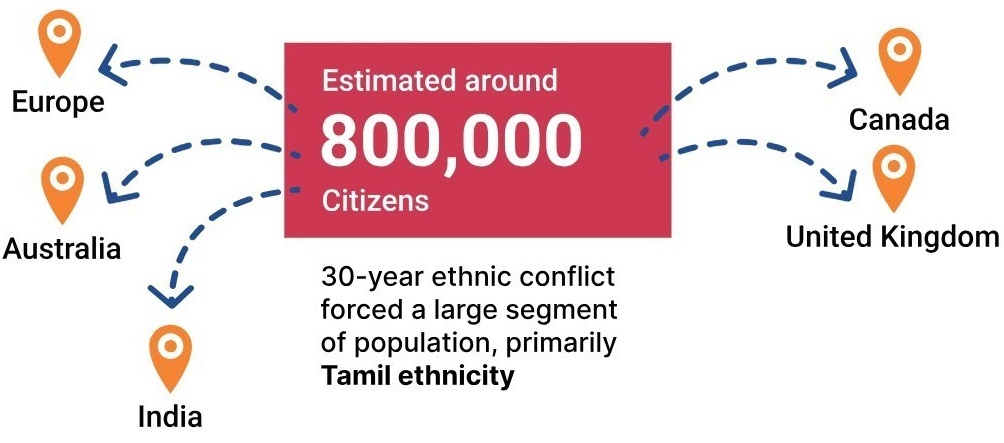

Sri Lanka is one of the contemporary world’s major emigration nations (Hugo 2014). For 40 years, its internal and international migration has been driven by two main push–pull factors. The 30-year ethnic conflict pushed a large segment of the population, estimated at around 800,000 citizens, primarily of Tamil ethnicity, into internal or international exile (Anandakugan 2020). Similarly, many were pulled to migrate by the prospect of better employment opportunities available elsewhere (ILO 2023).

Over decades of residence abroad, Sri Lanka’s international migrants have permanently settled in their host countries, mostly in Canada and the United Kingdom, or in Australia, India and European countries (Hugo 2014). The vast majority of those who emigrated are now citizens of their host countries. These migrants can vote in Sri Lanka if their citizenship has been retained and they are registered to vote. While the electoral register for the predominantly Tamil district of Jaffna, for example, makes allowance for the possibility of their return to vote in national and local elections, this is unaffordable and logistically complicated for most migrants, and thus highly unlikely.

Fig 4. Key destinations of Sri Lanka’s international migrants

The enfranchisement of internally displaced citizens has also been guaranteed by legal proceedings. Awareness campaigns are also conducted by the Election Commission of Sri Lanka, and seven different official documents can be used for identification purposes at polling stations (Shujaat, Roberts and Erben 2016).

Many skilled and unskilled workers migrate to the Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) states or the Middle East more generally (ILO 2017). They are drawn from all communities but are predominantly Sinhalese. These migrants leave Sri Lanka to pursue better economic opportunities than those available at home (Perera 2020), a phenomenon that dates to the economic liberalization of 1977. Domestic staff constitute a large proportion of migrants, and there have been high-profile cases of accusations of abuse and even murder against employers (HRW 2007).

3. Status of the electoral enfranchisement of Sri Lanka’s migrants

Sri Lanka introduced universal adult franchise almost a century ago, yet several areas of neglect remain in the country’s electoral systems and processes. Key among these areas is the challenge of enfranchising its migrants.

While the right to vote for migrants is normatively recognized, in practice unless they travel home, these absent voters have no opportunity to cast their votes as no viable absentee voting systems are in place.

The legal framework governing elections in Sri Lanka is scattered across various pieces of legislation.2 Article 4(e) of the Constitution stipulates that ‘the franchise shall be exercisable at the election of the President of the Republic and of Members of Parliament and at every Referendum by every citizen who has attained the age of eighteen years and who, being qualified to be an elector as hereinafter provided, has her/his name entered in the register of electors’. As established in the Registration of Electors Act (No. 44 of 1980) and the Parliamentary Elections Act (No. 1 of 1981), postal voting before the day of an election, or ‘advanced voting provisions’, is limited to specific categories of voter such as the police, members of the armed forces, public servants engaged in election work and support staff such as bus, railway and postal workers. Until 2020 doctors working in intensive-care units, nurses and attendants were not allowed postal ballots. Those working in the tourism industry and at airports are still not allowed early postal voting.

According to articles 41 and 84 of the 1990 International Convention on the Protection of the Rights of All Migrant Workers and Members of Their Families3 (ICRMW), ratified by Sri Lanka in 1995, ‘migrant workers … have the right to participate in public affairs of their State of origin and to vote and be elected at elections of that State’. Sri Lanka, as a signatory, should facilitate the enfranchisement of its migrants.

Several parliamentary and presidential committees (Weeraratne 2024) have been set up to address this long-standing challenge, often following intense civil society advocacy, and have received submissions from various stakeholders. However, either such initiatives have struggled to identify viable absentee voting solutions or their recommendations (Parliament of Sri Lanka 2022) did not have any follow up mostly because they lacked the necessary political consensus:

- Prior to the 2000 general elections, the National Congress4 and civil society groups appealed to the then Commissioner of Elections to facilitate the electoral participation of international migrants. Neither this request nor subsequent ones were successful (NDI 2000).

- In 2003, the International Labour Organization underlined the importance of inclusive electoral processes in Sri Lanka and argued that the enfranchisement of migrants was a major factor that could strengthen the country’s democratic process (Ahn 2004).

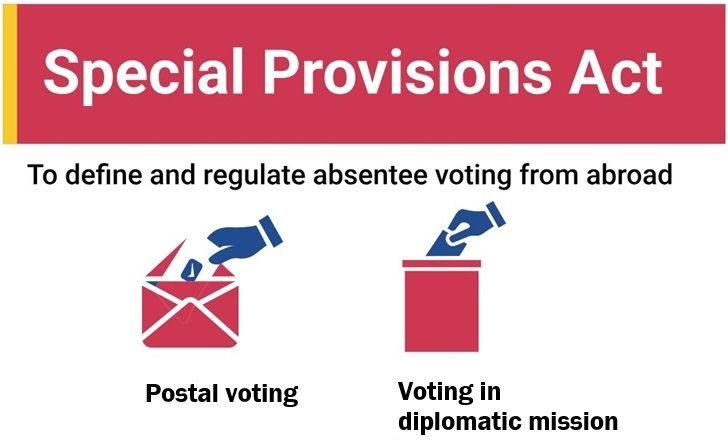

- In several instances, over the years, the Human Rights Commission of Sri Lanka (HRCSL) has recommended that suitable arrangements be made to ‘facilitate and ensure voting rights for Sri Lankan migrants’ in the respective countries of their employment/residence. In 2001, the HRCSL argued that the lack of voting rights for migrants could be considered as a violation of their human rights. The HRCSL recommended that the Migrants Service Centre (MSC) conduct a study of the legal mechanisms for absentee voting, including systems adopted by other countries (Sunday Times 2016). A group of lawyers and human rights activists was engaged by the MSC to conduct the study. The HRCSL examined two possible absentee voting systems—postal voting and voting at polling stations established in Sri Lankan diplomatic missions overseas. The HRCSL also recommended the adoption of a Special Provisions Act5 to define and regulate absentee voting abroad. These recommendations formed part of the HRCSL’s 2011–2016 Action Plan.

- In 2016, a parliamentary committee further investigated the possible adoption of out-of-country voting (OCV) in the country (Colombage 2017), but an election intervened, and the work of the committee ceased and was not resumed.

- On numerous occasions, the two main, national election monitoring organizations—People’s Action for Free and Fair Elections (PAFFREL) and the Centre for Monitoring Election Violence (CMEV)—have called for the adoption of provisions on absentee voting for migrants (CMEV 2016; Kuruwita 2024), but with little or no success.

- In June 2024, a 10-member Presidential Commission of Inquiry (PCoI), appointed by President Ranil Wickremesinghe in November 2023, submitted an electoral reform proposal outlining several key revisions to electoral laws. The primary goal of these reforms was to ‘align the country’s electoral framework with modern needs while enhancing the inclusiveness, integrity and transparency of political parties’ (Daily FT 2023). Among several key electoral reform issues, the PCoI proposed exploring electronic voting as a modern alternative to traditional paper ballots, particularly to facilitate voting for citizens residing abroad.

The issue of dual citizenship has also presented several complexities for the electoral enfranchisement of Sri Lanka’s absent voters. The authority to grant dual citizenship is vested in the Minister of Internal Security, Home Affairs and Disaster Management. Applications are examined on a case-by-case basis. The Citizenship Act (1987) states that ‘the Minister may make the declaration for which the application is made if he is satisfied that the making of such declaration would, in all the circumstances of the case, be of benefit to Sri Lanka’.

Sri Lanka’s dual-citizenship policy was suspended in 2011 but reinstated in 2015. The full impact of the dual-citizenship policy was not fully anticipated (Jayawardena 2020). Whether dual citizens should have all the rights of citizenship or restrictions should be imposed, given dual citizens’ possible additional and even competing allegiances, became a matter of heated debate. The 19th Amendment to the Constitution restricted dual citizens from entering parliament, and a parliamentarian who was a dual citizen had to give up her/his seat (Samarawickrama 2017). The 20th Amendment to the Constitution, passed in October 2020, removed the restriction on dual citizens holding elected office for partisan and political reasons (Weerawardhana 2020). This amendment reversed many of the reforms introduced by the 19th Amendment in 2015, which had previously barred dual citizens from contesting elections and becoming members of Parliament (CPA 2020).

In response to the political and economic turmoil that enveloped Sri Lanka in 2022, the government enacted the 21st Amendment to the Constitution which reintroduced restrictions on dual citizens entering Parliament adopted through the 20th Amendment in 2020. Public conversation around the issue created more confusion, as ministers stated that members of Parliament with dual citizenship could be removed only if their status was challenged in the courts (EconomyNext 2022); others instead claimed that dual citizens should have resigned voluntarily (Daily Mirror 2022). This suggested that the 21st Amendment lacked teeth and had weak enforcement mechanisms.

However, the 22nd Amendment, enacted in October 2022, reintroduced once again a prohibition on dual citizens holding parliamentary seats (Kuruwita 2022). The amendment’s passage was met with significant political discourse, reflecting differing perspectives on the role of dual citizens in governance: some contended that permitting dual citizenship was a measure to ensure that Sri Lankans abroad were incentivized to remain connected with the country, and that Sri Lanka would benefit from their skills and experience, as well as the resources that they might invest in the country; others regarded the ban as necessary to maintain national integrity (Kuruwita 2022).

The attitude to dual citizenship reflects the polarization in the country, especially when focused on members of the Tamil minority community seeking dual citizenship (Jayawardena 2020).

4. Challenges to the electoral enfranchisement of Sri Lankan migrants

Several challenges have been identified in addressing the enfranchisement of Sri Lanka’s migrants, leading to a prolonged period of inaction. Since 1998, a coalition of civil society groups led by the MSC of the National Congress, joined by PAFFREL and the CMEV, has been advocating for parliamentary action to amend the election law and establish an OCV system to enfranchise Sri Lanka’s absent voters. While most electoral stakeholders, including political parties and the Department of Elections,6 expressed support for this initiative, the issue languished at the bottom of the list of parliamentary priorities.

Concerns about organizing and implementing OCV have broadly focused on the security, integrity and transparency of the system, the associated costs and logistical complications. Additional issues include managing voter registration for those abroad to prevent double voting and determining whether voting at diplomatic missions, staffed by political appointees, would be trusted by migrants (IOM 2006). However, there is little evidence that efforts have been made to realistically explore ways to overcome these challenges.

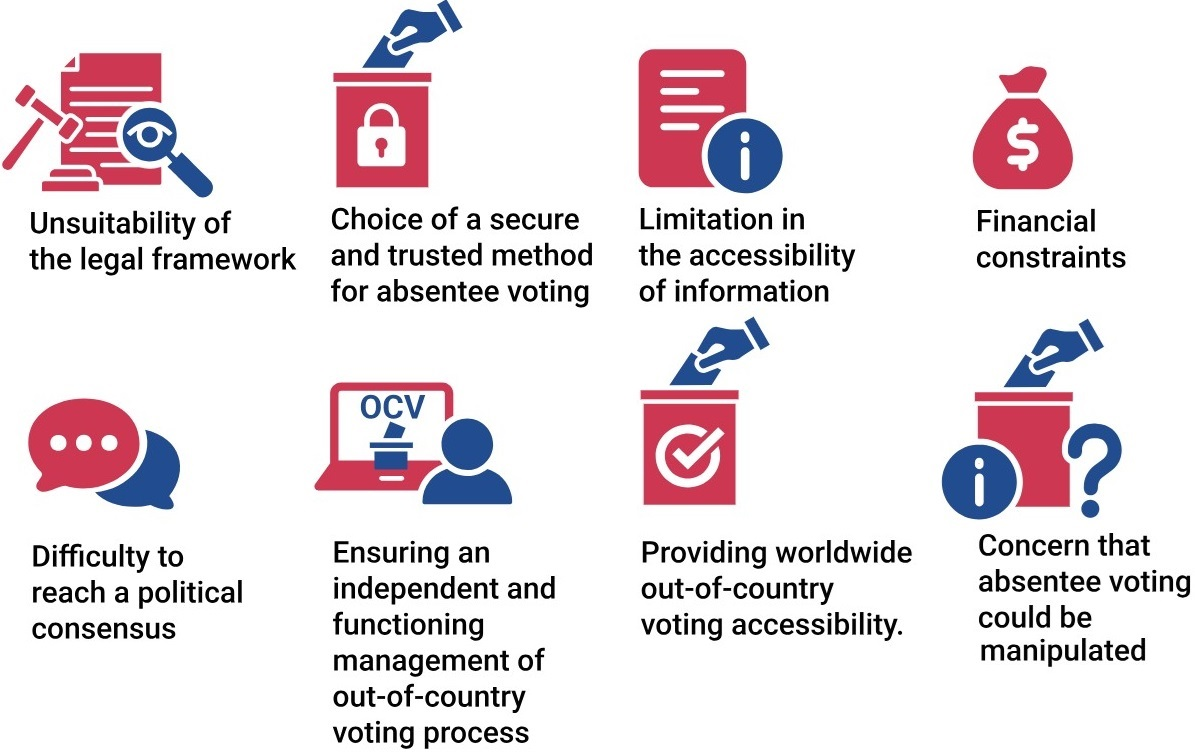

Key challenges therefore remain, as follows:

- Reform of the legal framework of elections. Without a reformed, facilitating framework of national legislation, neither the SLBFE nor the National Election Commission (EC) can act to enfranchise Sri Lanka’s absent voters. As long as lawmakers fail to recognize this need and to act, the largest earners of foreign exchange for the country will continue to be systematically disenfranchised, and the legitimate exercise of their voting rights will remain moot. Amendments to existing electoral law will be required to enable migrant voters to register and vote, remotely, from their places of employment.

- Choice of a secure method for absentee voting. In 2015 Minister for Foreign Employment Thalatha Atukorale recognized that the government had only a limited ability to guarantee voting rights for all Sri Lankan nationals working abroad, and expressed concerns that the adoption of absentee voting, and Internet voting in particular, might open the door for electoral fraud and malpractice (Roland 2015). The minister made these remarks in response to a 3,200-signature petition from migrants advocating for their voting rights presented by Ethera Api, a Sri Lankan organization active in protecting the rights of migrants. In response to the petition, the minister acknowledged that the Foreign Employment Ministry had been unable to provide viable solutions and stressed the need for more effective cooperation among government agencies and the Department for Elections (now the EC) (Roland 2015).

- Accessibility of information. Migrant communities overseas would need broad access to election information. Leaving this crucial aspect to political parties, not all of which have offices abroad, would likely privilege wealthier parties and candidates, prevent the creation of a level playing field for electioneering and possibly encourage the diffusion of partisan information.

- Financial constraints. It has been argued that the introduction of an OCV system to enfranchise migrants would be prohibitively expensive for Sri Lanka, as it would require a special registration process for voters overseas, civic education on voting procedures (for either polling booths or postal ballots) and voting materials to be sent to voters scattered across many countries, often far from the capital of, or major cities in, those countries. Further, the number of elections in Sri Lanka at the different tiers—presidential, parliamentary, provincial and local government—also make the provision of election infrastructure and materials for all of them prohibitively expensive (Rajapaksha 2024).

- Need for broad political consensus. All key electoral stakeholders, from political parties to the EC, SLBFE and civil society organizations, would be required to agree on the modalities of an OCV system that is satisfactory to them and on the cost of its adoption and implementation in the long term. There would also have to be a political consensus that facilitating the enfranchisement of migrants is a priority for the country. The argument that only the large and wealthy political parties will be able to reach out to migrant voters living and working overseas may have some merit, but it is not entirely tenable that governments cannot invest in maximizing electoral participation and representation by including eligible citizens living overseas.

- Independent and viable management of the OCV process. Additional challenges relate to concerns about the ability of the diplomatic staff working at Sri Lanka’s diplomatic missions abroad who would have to supervise the OCV process to be non-partisan. There are also questions about the reliability of the postal services that would have to be used for OCV. Ballot papers would have to be transported through the diplomatic post. This operation would be compounded by the limitations on the powers of the EC and the power of the president7 to effectively appoint members to this body. The issue of the credibility and integrity of state institutions is a systemic problem of democratic governance in Sri Lanka, which has been exacerbated by the 20th Amendment, as well as by the fact that numerous institutional reforms have been suggested to deal with this issue and the raft of other problems it gives rise to.

- Voting accessibility. An additional challenge is to enable migrants to gain access to the OCV facilities established at Sri Lanka’s diplomatic missions abroad to obtain and return their postal ballots. Conditions for migrants are particularly difficult in the GCC states and the broader Middle East. Numerous reports have exposed the practice of employers retaining and withholding the identity documents of their employees for the duration of their contracts (HRW 2013). In such instances, it is incumbent on the government to strengthen its laws on the protection of migrants. The enfranchisement of migrants would be a step in the right direction. Governments have, at times, downplayed the need for protections, fearing a reduction in migrant remittances (US DoS n.d.). This is especially true in cases where female migrants have reported sexual abuse or harassment while working in Gulf countries (HRW 2007), with authorities often reluctant to raise these issues with the respective missions. Allegations of official complicity have surfaced, as the government has sometimes failed to report or investigate instances of abuse. Few convictions have been achieved, and efforts to identify Sri Lankan victims of forced labour abroad have been inadequate (US DoS n.d.). Additionally, the SLBFE often handles migrant labour complaints administratively—many of which indicate forced labour—rather than referring them to the police for potential trafficking investigations (US DoS n.d.). In some instances, voters do not see any value in registering to vote. There is also the issue of the unwillingness of migrants who are not registered with the SLBFE to come into the open to vote.

5. Prospects for the electoral enfranchisement of Sri Lankan migrants

The above challenges to enfranchising absent voters are neither unique to Sri Lanka nor insurmountable. The failure to address them therefore appears to be a failure of political will and a result of inadequate pressure from civil society.

Sri Lanka’s development strategy is increasingly founded on migrants, and as the economic crisis worsens, there is more pressure to increase the number of migrants. The push factor is great, and there is less focus on the rights and protection of migrants. The discourse around migrants is on how to maximize their economic agency and not on their rights. This neglect is tied to a broad range of rights concerning their health and safety, as well as their economic and political rights, among others. Pushing people to work overseas not only deprives Sri Lanka of both skilled and unskilled people to engage in productive work inside the country but also deprives the country of engaged citizens as voters and stakeholders in the country’s political economy.

The Government of Sri Lanka has labelled these groups ‘migrant heroes’ and publicly celebrates their sacrifice as agents of development for kin and country (Withers 2020). In August 2022 a new position of goodwill ambassador was created to promote the welfare of Sri Lankan migrants. It is an unpaid position, and the post was filled by a former parliamentarian who was recently pardoned and released from jail for contempt of court (LankaWeb 2022). In addition, a Hope Gate was created at Bandaranaike International Airport in Katunayake to streamline procedures for departing and returning migrants (Daily FT 2022). These measures are merely symbolic and cosmetic, however, and such gestures cannot substitute for the political empowerment that flows from the right to vote, choose representatives, and have a voice in the future of the country and the protection of one’s own rights.

Electoral reform aimed at enfranchising Sri Lanka’s absent voters has been repeatedly assessed, in 2021 by a parliamentary committee and later, in 2024, by a presidential commission. However, it should be noted that recognition and acknowledgement of the importance of the issue by these initiatives did not automatically translate into parliamentary action as far as legislation was concerned.

In terms of lobbying on the issue by wider civil society and migrant workers’ groups, it has been suggested that all migrant worker recruitment agencies should be brought together under one roof, and that the resulting organization should take on responsibility for lobbying (ILO 2013). In addition, civil society organizations could lobby the government to enter into bilateral agreements with host countries to facilitate voting and other issues pertaining to migrants, including their treatment and working conditions in the host country. In 2012, for instance, the US labour organization Solidarity Center worked with its partners in Sri Lanka to establish formal cooperation between Qatar’s National Human Rights Committee and the HRCSL on protection of the rights and safety of Sri Lankan migrants in Qatar. This work included a discussion of the need for a single, common contract endorsed by government agencies in both countries and legal remedies for any violations of contracts in Qatar (Sunday Times 2012). Qatar hosts around 130,000 Sri Lankan migrants.

One of the most successful support systems for migrants is the partnership between the National Workers Congress (NWC), an independent labour federation, and the MSC. Through this partnership, the MSC has gained legal status along with the resources and networks of the formalized trade union structure of the NWC. Thus, under this umbrella, the MSC can, in addition to directing assistance to migrants and their families, emphasize the importance of migrant workers’ voting rights and lobby the legislature.

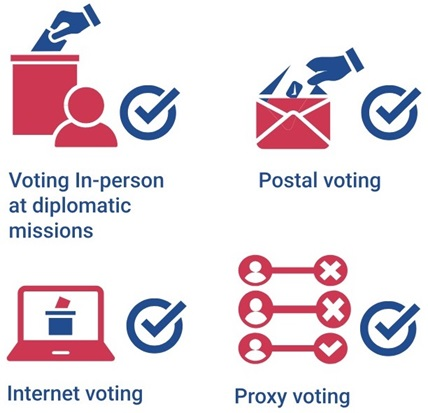

An array of absentee voting methods and practices, alone or combined, could be studied in depth as viable solutions for enfranchising Sri Lanka’s migrants. These include the following:

- Voting in person at diplomatic missions. This method would inevitably require the establishment of polling stations on diplomatic mission premises in locations where diaspora populations are concentrated. However, implementation of such a system presents challenges since such mobilization would require intergovernmental negotiations with the host country to allow the establishment of such polling stations on their territory. An additional complication is that consulates and diplomatic missions tend to be located only in host country capitals or main cities; thus, such an absentee voting method would be neither convenient nor affordable for many migrants who are dispersed throughout the host country. Particularly in the GCC states and Middle East, where Sri Lankan women are employed as domestic staff, OCV conducted at diplomatic missions requires a cumbersome process of seeking the approval of employers and travelling a long distance to both register and vote.

- Postal voting. With this method, ballots are mailed out to registered out-of-country voters to be completed and returned by mail in time for counting. They can be returned to collection points in host countries, such as diplomatic missions, or directly back to the electoral management body in the home country. However, there are sensitivities around the security and reliability of involving postal services in the OCV process.

- Internet voting. Internet voting is a new voting method that addresses many of the complexities involved in in-person voting. However, it requires a population that is comfortable with technology, as well as political consensus and broad public trust in its adoption. Furthermore, the technology available for Internet voting is still in its initial stages. Therefore, this system is not recommended for adoption unless proper methods of security and voter identification are in place.

- Proxy voting. This system uses a proxy who lives in the home country who is chosen by the registered out-of-country voter to cast a vote on his or her behalf. Few countries place much faith in such a system, as it is regarded to be prone to irregularities, fraud and vote buying, and such a system might not be suitable for Sri Lanka.

The pandemic laid bare the vulnerability of migrant voters. Migrants are valued for their economic contribution to the country, on the one hand, but not regarded as people with agency and rights, on the other. Non-recognition of or indifference to migrants’ rights leads directly to their exploitation.

Ultimately, the key issue about enfranchising Sri Lanka’s absent voters is that of political will or commitment. Submissions by civil society to the various bodies established to address electoral reform needs have raised the issue. Whether the interests of migrants will be considered, and the gross injustices against this key sector of the Sri Lankan polity and economy rectified, remains to be seen.

Abbreviations

CMEV Centre for Monitoring Election Violence

GCC Gulf Cooperation Council

ICRMW International Convention on the Protection of the Rights of All Migrant Workers and Members of Their Families

EC Election Commission

HRCSL Human Rights Commission of Sri Lanka

LKR Sri Lankan rupee

MSC Migrants Service Centre

NWC National Workers Congress

OCV Out-of-country voting

PAFFREL People’s Action for Free and Fair Elections

PCoI Presidential Commission of Inquiry

SLBFE Sri Lanka Bureau of Foreign Employment

References

P.-S. Ahn (ed.), Migrant Workers and Human Rights: Out-Migration from South Asia (New Delhi: International Labour Organization, 2004),<https://www.ilo.org/sites/default/files/wcmsp5/groups/public/%40asia/%40ro-bangkok/%40sro-new_delhi/documents/publication/wcms_124657.pdf>, accessed 20 November 2024

Anandakugan, N., ‘The Sri Lankan Civil War and Its History, Revisited in 2020’, Harvard International Review (HIR), 31 August 2020, <https://hir.harvard.edu/sri-lankan-civil-war/>, accessed 25 November 2024

Central Bank of Sri Lanka, ‘Annual Report 2019’, <https://www.cbsl.gov.lk/en/publications/economic-and-financial-reports/annual-reports/annual-report-2019>, accessed 27 October 2024

Centre for Monitoring Election Violence (CMEV), ‘First consultative meeting on out-of-country voting’, 18 October 2016, <https://cmev.org/2016/10/18/first-consultative-meeting-on-out-of-country-voting>, accessed 20 November 2024

Centre for Policy Alternatives (CPA), ‘A brief Q and A on the Proposed 20th Amendment to the Constitution’, Research and Advocacy paper, 17 September 2020, <https://www.cpalanka.org/a-brief-q-and-a-on-the-proposed-20th-amendment-to-the-constitution/>, accessed 24 November 2024

Colombage, Q., ‘Voting rights of Sri Lankan migrant workers ‘‘not a priority’’’, Union of Catholic Asian News (UCA News), 30 June 2017, <https://www.ucanews.com/news/voting-rights-of-sri-lankan-migrant-workers-not-a-priority/79629>, accessed 25 November 2024

Daily FT, ‘Govt. opens special ‘HOPE GATE’ for expatriate workers’, 3 September 2022, <https://www.ft.lk/front-page/Govt-opens-special-HOPE-GATE-for-expatriate-workers/44-739438>, accessed 24 November 2024

—, ‘President appoints Commission to amend the electoral laws to suit the present needs’, 4 November 2023, <https://www.ft.lk/news/President-appoints-commission-to-amend-electoral-laws-to-suit-present-needs/56-754844>, accessed 25 November 2024

Daily Mirror, ‘Channa Jayasumana says 10 MPs with dual citizenship should resign’, 21 October 2022, <https://www.dailymirror.lk/breaking_news/Channa-Jayasumana-says-10-MPs-with-dual-citizenship-should-resign/108-247250>, accessed 27 October 2024

EconomyNext, ‘Dual citizens in Sri Lanka’s parliament can stay on unless challenged in court: Justice minister’, 25 October 2022, <https://economynext.com/dual-citizens-in-sri-lankas-parliament-can-stay-on-unless-challenged-in-court-justice-minister-101441/>, accessed 27 October 2024

Hugo, G., ‘The Process of Sri Lankan Migration to Australia Focussing on Irregular Migrants Seeking Asylum’, Irregular Migration Research Programme Occasional Paper Series 10 (2014), <https://www.homeaffairs.gov.au/research-and-stats/files/process-sri-lanka-migration.pdf>, accessed 13 November 2024

Human Rights Watch (HRW), ‘Middle East: Sri Lankan domestic workers face abuse: Labor laws leave migrant women exposed’, 13 November 2007, <https://www.hrw.org/news/2007/11/14/middle-east-sri-lankan-domestic-workers-face-abuse>, accessed 23 November 2024

—, ‘South Asia: Protect migrant workers to Gulf countries: Seek reforms in sponsorship system, labor rights protections’, 18 December 2013, <https://www.hrw.org/news/2013/12/18/south-asia-protect-migrant-workers-gulf-countries>, accessed 25 November 2024

International Labour Organization (ILO), Recruitment Practices of Employment Agencies Recruiting Migrant Workers (Geneva: ILO Country Office for Sri Lanka and the Maldives, 2013),<https://www.ilo.org/sites/default/files/wcmsp5/groups/public/%40asia/%40ro-bangkok/%40ilo-colombo/documents/publication/wcms_233363.pdf>, accessed 24 November 2024

—, Labour Market Trends & Skills Profiles of Sri Lankan Migrant Workers in the Construction Industry in GCC Countries (ILO and International Organization for Migration, 2017), <https://www.ilo.org/publications/labour-market-trends-and-skills-profiles-sri-lankan-migrant-workers>, accessed 21 November 2024

—, Labour Market Supply and Demand for Sri Lankan Migrant Workers (Colombo: ILO, 2023), <https://www.ilo.org/sites/default/files/2024-06/Report-Labour%20Market-Migrant%20Workers-SriLanka-2023.pdf>, accessed 25 November 2024

International Organization for Migration (IOM) Sri Lanka, ‘The Voting Rights of Internally Displaced Persons, Refugees and Economic Migrants: Political Rights and Enfranchisement System Strengthening (PRESS)’, Action Plan V, Final Report, April 2006

Jayatilaka, C., ‘Return of overseas Sri Lankans: A look at the visa processes and lessons from our neighbours’, Daily FT, 21 January 2020, <https://www.ft.lk/Opinion-and-Issues/Return-of-overseas-Sri-Lankans-A-look-at-the-visa-processes-and-lessons-from-our-neighbours/14-693953>, accessed 27 October 2024

Jayawardena, P., ‘A Comparative Analysis of Sri Lankan and Global Dual Citizenship Trends’, University of Colombo, December 2020,<https://www.researchgate.net/publication/347558374_A_Comparative_Analysis_of_Sri_Lankan_and_Global_Dual_Citizenship_Trends>, accessed 20 November 2024

Kuruwita, R., ‘Sri Lankan President’s grip over power turns more tenuous’, The Diplomat, 26 October 2022, <https://thediplomat.com/2022/10/sri-lankan-presidents-grip-over-power-turns-more-tenuous/>, accessed 22 November 2024

—, ‘‘‘Low’’ voter turnout linked to mass emigration – PAFFREL’, The Island Online, 28 September 2024, <https://island.lk/low-voter-turnout-linked-to-mass-emigration-paffrel/>, accessed 24 November 2024.

LankaWeb, ‘Ranjan accepts new position as goodwill ambassador for migrant workers’, 26 August 2022, <https://www.lankaweb.com/news/items/2022/08/26/ranjan-accepts-new-position-as-goodwill-ambassador-for-migrant-workers>, accessed 24 November 2024

Mittal, A. and Fraser, E., ‘Waiting to Return Home: Continued Plight of the IDPs in Post-war Sri Lanka’, Oakland Institute (2016), <https://www.oaklandinstitute.org/sites/oaklandinstitute.org/files/SriLanka_Return_Home_final_web.pdf>, accessed 12 November 2024

National Democratic Institute for International Affairs (NDI), ‘Report of the Post-Election Assessment of Sri Lanka Mission, 28 December 2000, <https://www.ndi.org/sites/default/files/1198_lk_postelect122000_5.pdf>, accessed 25 November 2024

Office for Overseas Sri Lankan Affairs (OOSLA), ‘The Office for Overseas Sri Lankan Affairs (OOSLA) marks the International Migrants Day 2023’, press release, 2023, <https://oosla.lk/the-office-for-overseas-sri-lankan-affairs-oosla-marks-the-international-migrants-day-2023-launches-an-online-platform-to-enhance-connectivity-with-the-overseas-sri-lankans/>, accessed 25 November 2024

Parliament of Sri Lanka, ‘Final Report of the Select Committee of Parliament to Identify Appropriate Reforms of the Election Laws and the Electoral System and to Recommend Necessary Amendments presented to Parliament’, press release, 25 June 2022, <https://www.parliament.lk/news-en/view/2628>, accessed 12 November 2024

Perera, E. L. S. J., ‘Internal migration in Sri Lanka’, in M. Bell, A. Bernard, E. Charles-Edwards and Y. Zhu (eds), Internal Migration in the Countries of Asia: A Cross-national Comparison (Cham, Switzerland: Springer, 2020),<https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-44010-7_14>

Rajapaksha, N., ‘Shifting spending patterns: Sri Lanka’s 2024 general elections’, Westminster Foundation for Democracy, 21 November 2024, <https://www.wfd.org/commentary/shifting-spending-patterns-sri-lankas-2024-general-elections>, accessed 25 November 2024

Roland, N., ‘Let Sri Lankan migrants vote: Church activists’, Union of Catholic Asian News (UCA News), 20 November 2015, <https://www.ucanews.com/news/church-rights-groups-demand-voting-rights-for-sri-lankan-migrants/74643>, accessed 22 November 2024

Samarawickrama, C. P., ‘Court rules Geetha disqualified to be MP’, Daily Mirror, 3 May 2017, <https://www.dailymirror.lk/breaking_news/Court-rules-Geetha-disqualified-to-be-MP/108-128196>, accessed 27 October 2024

Shujaat, A., Roberts, H. and Erben, P., ‘Internally Displaced Persons and Electoral Participation: A Brief Overview’, IFES White Paper, International Foundation for Electoral Systems (IFES), September 2016, <https://www.ifes.org/sites/default/files/migrate/idps-electoral-participation-october-2016.pdf>, accessed 22 November 2024

Sri Lanka Brief, ‘Sri Lanka: Only 22% of FTZ workers allowed to vote’, 24 October 2024, <https://srilankabrief.org/sri-lanka-only-22-of-ftz-workers-allowed-to-vote>, accessed 19 November 2024

Sri Lanka Bureau of Foreign Employment (SLBFE), ‘Statistics 2022’, Outward Labour Migration in Sri Lanka (2022), <https://www.slbfe.lk/wp-content/uploads/2023/09/Statistics-2022.pdf>, accessed 25 November 2024

Sriskandarajah, D., ‘The migration–development nexus: Sri Lanka case study’, International Migration, 40/5 (2002), Special Issue 2, pp. 283–307, <https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-2435.00220>

The Sunday Times, ‘Qatar HRC, Lankan human rights body sign MoU’, Business Times, 16 December 2012, <https://www.sundaytimes.lk/121216/business-times/qatar-hrc-lankan-human-rights-body-sign-mou-24309.html>, accessed 24 November 2024

—, ‘Voting rights to migrant workers’, Business Times, 17 April 2016, <https://www.sundaytimes.lk/160417/business-times/voting-rights-to-migrant-workers-189682.html>, accessed 23 November 2024

United Nations Children's Fund (UNICEF), ‘Sri Lanka’s initial social protection response to Covid-19: An analysis of who benefits and who does not’, April 2020, <https://www.unicef.org/srilanka/media/1636/file/An%20analysis%20of%20who%20benefits%20and%20who%20does%20not.pdf>, accessed 23 November 2024

United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs (UN DESA), International Migration 2020 Highlights (UN DESA Population Division, 2020), <https://www.un.org/development/desa/pd/sites/www.un.org.development.desa.pd/files/undesa_pd_2020_international_migration_highlights.pdf>, accessed 10 November 2024

United States Department of State (US DoS), Office to Monitor and Combat Trafficking in Persons, ‘Trafficking in Persons 2021 Report: Sri Lanka’, [n.d.], <https://www.state.gov/reports/2021-trafficking-in-persons-report/sri-lanka>, accessed 27 October 2024

Weeraratne, B., ‘COVID-19 and foreign exchange woes: Can Sri Lanka find a way out?’, blog, Institute of Policy Studies of Sri Lanka (IPS), 17 April 2020, <https://www.ips.lk/talkingeconomics/2020/04/17/covd-19-and-foreign-exchange-woes-can-sri-lanka-find-a-way-out/>, accessed 17 November 2024

—, ‘Voting beyond borders: Can overseas Sri Lankans finally have their say?’, blog, Institute of Policy Studies of Sri Lanka (IPS), 5 November 2024, <https://www.ips.lk/talkingeconomics/2024/11/05/voting-beyond-borders-can-overseas-sri-lankans-finally-have-their-say>, accessed 25 November 2024

Weerawardhana, C., ‘Dual citizenship restriction: Time for change’, The Colombo Telegraph, 6 September 2020, <https://www.colombotelegraph.com/index.php/dual-citizenship-restriction-time-for-change/>, accessed 25 November 2024

Withers, M., ‘The pitfalls of Sri Lanka’s remittance economy’, East Asia Forum, 5 February 2020, <https://www.eastasiaforum.org/2020/02/05/the-pitfalls-of-sri-lankas-remittance-economy>, accessed 27 October 2024

About the author

Paikiasothy Saravanamuttu, PhD, is the founder and Executive Director of the Centre for Policy Alternatives, a co-convenor of the Centre for Monitoring Election Violence, a member of the Advisory Board of the Berghof Foundation for Peace Support and a Secretary to the Consultative Task Force on Reconciliation Mechanisms (2016). He was a founding member of the Board of the Sri Lanka chapter of Transparency International and served on the Board until June 2009. Saravanamuttu holds a PhD from the London School of Economics.

About this series

This case study is part of the ‘Absent Voters of South Asia’ project, which falls under the project of ‘Migrations and Elections’ that covers member states of the South Asian Council for Regional Cooperation (SAARC), such as Afghanistan, Bangladesh, Bhutan, India, the Maldives, Nepal, Pakistan and Sri Lanka.

- According to the SLBFE, in 2018, approximately 211,459 Sri Lankans departed for foreign employment. This translates to an average of about 580 individuals leaving the country daily for overseas work opportunities.

- The Constitution of Sri Lanka; parts of the Election Ordinance of 1946 still effective to date; the Parliamentary Elections Act, No. 1 of 1981; the Presidential Elections Act, No. 15 of 1981; the Referendum Act, No. 7 of 1981; the Provincial Councils Elections Act, No. 2 of 1988; the Local Authorities Elections Ordinance (chapter 262); the Local Authorities Elections Ordinance, No. 53 of 1946, and amendments thereto; the Local Authorities Elections Amendment Act, No. 22 of 2012; and the Local Authorities Elections Act, No. 1 of 2016.

- The ICRMW is a comprehensive international treaty adopted by the United Nations General Assembly, Resolution 45/158, on 18 December 1990. The Convention aims to protect the rights of migrant workers and their families, emphasizing the link between migration and human rights.

- Founded in 2004, the National Congress is a registered political party in Sri Lanka.

- In Sri Lanka, a Special Provisions Act refers to legislation enacted to address specific issues or circumstances that are not adequately covered by existing laws. These acts introduce targeted measures to manage unique situations, often providing temporary or supplementary legal frameworks.

- The Department of Elections was, at the time, the body formally responsible for conducting elections. However, it was reconstituted as the National Election Commission (EC) in November 2015, following the enactment of the 19th Amendment.

- Under the 20th Amendment to the Constitution of Sri Lanka, passed on 22 October 2020, the president has the power to appoint members of the EC on the recommendation of the Parliamentary Council.

© 2024 International Institute for Democracy and Electoral Assistance

International IDEA publications are independent of specific national or political interests. Views expressed in this publication do not necessarily represent the views of International IDEA, its Board or its Council members.

With the exception of any third-party images and photos, the electronic version of this publication is available under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 (CC BY-NC-SA 4.0) licence. You are free to copy, distribute and transmit the publication as well as to remix and adapt it, provided it is only for non-commercial purposes, that you appropriately attribute the publication, and that you distribute it under an identical licence. For more information visit the Creative Commons website: <http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/4.0>.

Design and layout: International IDEA

DOI: <https://doi.org/10.31752/idea.2024.105>

ISBN: 978-91-7671-858-2 (PDF)

ISBN: 978-91-7671-925-1 (HTML)