The Absent Voters of Pakistan

Challenges and Prospects for the Enfranchisement of Migrants

Introduction

Pakistan’s history and geographic location have made it a major migration hub. From the mass movements triggered by partition to ongoing internal and international population flows, migration has shaped—and continues to shape—the country’s political, social and economic landscape.

This case study explores the multifaceted drivers of Pakistan’s migration, spanning from economic conditions and climate change to political instability and conflict. It then examines the complex issue of electoral enfranchisement for Pakistan’s internal and international migrants, highlighting the historical debates and recent developments in attempting to introduce absentee voting and outlining several challenges that continue to hinder the political participation of these absent voters.

Despite attempts to adopt innovative voting methods—such as an Internet voting (i-Voting) system and electronic voting machines (EVMs)—extending access to suffrage for Pakistan’s internal and international migrants remains an unresolved and controversial issue.

The study concludes by highlighting several prospects for making Pakistan’s electoral processes more inclusive and participatory. It emphasizes the need for a conducive political environment for meaningful legal reform, enhanced institutional and operational capacities for the Election Commission of Pakistan (ECP) and increased public awareness about voting among the electorate. The study stresses that the viability of these prospects depends heavily on concerted efforts, political will and consensus building among the country’s key political and electoral stakeholders.

1. Pakistan’s migration: Context and characteristics

Pakistan’s location at the crossroads of South Asia, Central Asia and the Middle East has historically positioned it as a bridge between Asia and Europe. As a result, it serves as a country of origin, transit and destination for migrants (IOM 2019).

When, in 1947, India and Pakistan obtained independence, the process of partitioning the subcontinent into two separate states led to the world’s largest and bloodiest mass-migration flows. Partition involved the migration of over 15 million people, an estimated 2 million of whom were killed in intercommunal riots and attacks targeted at migrating communities. The task of integrating these migrating populations into Pakistan was complex and took almost a quarter of a century (Riggs and Jat 2016).

In 1971, the secession of East Pakistan and the formation of Bangladesh led to significant migration crises. The conflict resulted in approximately 10 million East Pakistani refugees fleeing to India, with many housed in refugee camps across states such as Assam, Bihar, Meghalaya, Tripura and West Bengal (Sarkar 2021). Additionally, the war caused internal displacement within East Pakistan, with millions forced to leave their homes due to the violence (Biswas 2023). The aftermath of the conflict also saw the displacement of Bihari Muslims, who had migrated to East Pakistan during the 1947 partition. Post-independence, many Biharis faced persecution and were confined to refugee camps in Bangladesh and often denied citizenship rights (Hussein and Khan 2023). Karachi currently has a population of over 2.5 million Bengali-speaking migrants, while approximately 300,000 Bihari Muslims are living in 66 camps in Dhaka (Bukhari 2023). Bengali residents in Pakistan, particularly in Karachi, have faced significant challenges regarding citizenship and voting rights (Mughal and Naqvi 2018). The lack of official identification documents among stateless Bengalis in Pakistan further exacerbates their exclusion from political processes and access to essential services (Maryam 2021).

Pakistan experiences both regular and irregular flows of internal and international migration. Regular migration is managed primarily by the Bureau of Emigration & Overseas Employment (BEOE), while irregular flows occur via human trafficking networks, mainly to Australia, Europe and the United States (UNODC 2012). The Covid-19 pandemic severely impacted international migration, prompting many migrants to return to Pakistan (Ali, Akhtar and Ali 2023).

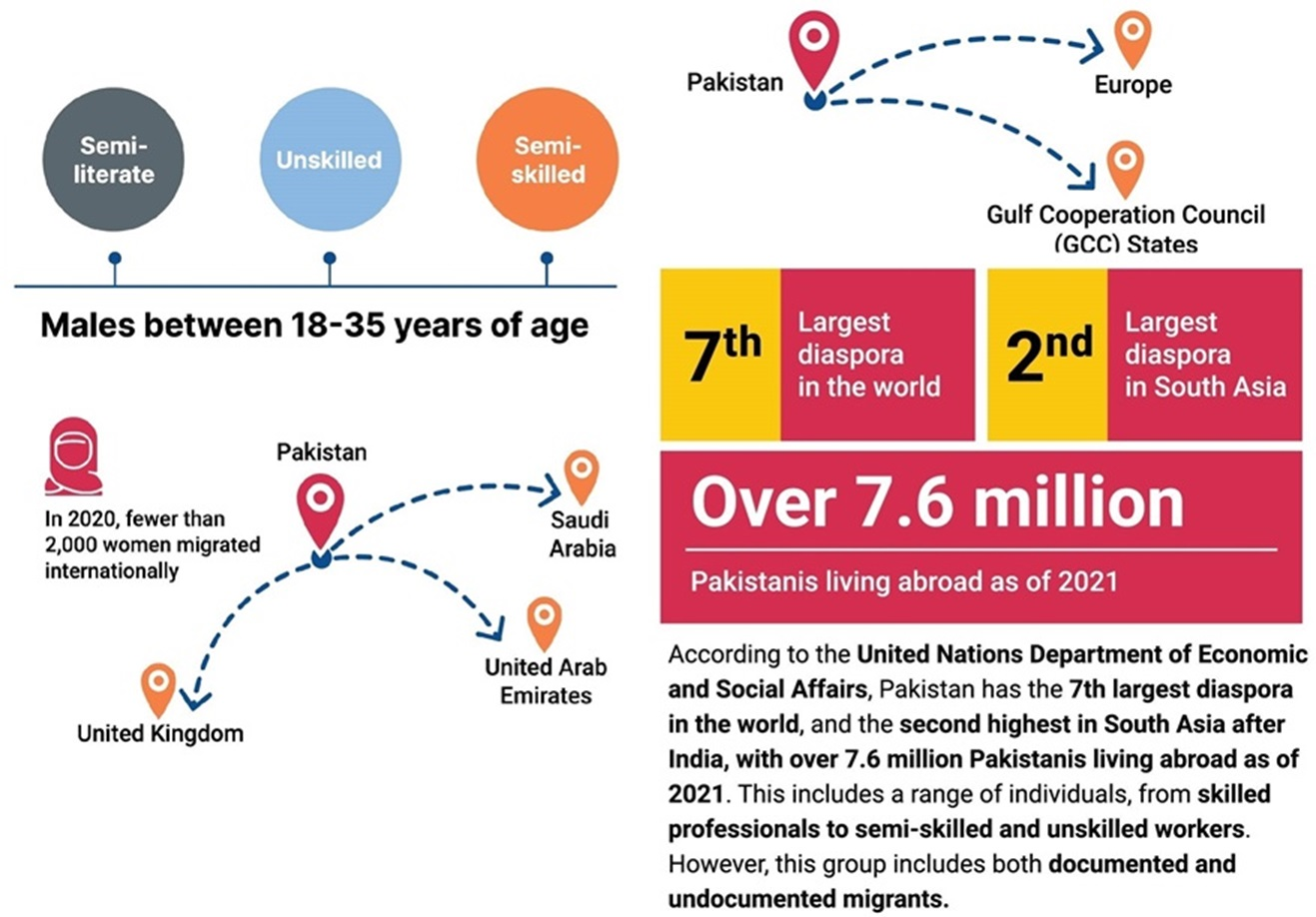

Determining the exact number of Pakistani international migrants is challenging due to varying definitions, data collection methods and reporting standards among different organizations. For instance, the World Migration Report 2022 by the International Organization for Migration (IOM) estimates that approximately between 6.3 and 8.8 million Pakistanis reside abroad, constituting about 2.7 per cent of the country’s population. In contrast, Pakistan’s Ministry of Overseas Pakistanis and Human Resource Development reports a higher figure of around 8.8 million overseas Pakistanis, with a significant concentration in Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) states.1 As of 2020, Pakistan ranked seventh among countries with the largest emigrant populations.

This migrant population ranges from highly skilled professionals to semi-skilled and unskilled workers (Sarwar 2023). World Bank data shows net emigration of around 1.1 million people from Pakistan between 2010 and 2020, indicating more people left than entered the country (World Bank 2022). However, this accounts for officially documented migration only while, due to the clandestine nature of irregular migration, the number of undocumented Pakistani migrants remains unknown but is estimated to be significant (Laczko and McAuliffe 2016).

The main destinations for Pakistan’s international migrants are European countries and the GCC states (BEOE 2020).2 International migration flows are generally long term, unless they are curtailed by the strict immigration policies of host countries or the materializing of favourable economic opportunities in Pakistan (BEOE 2020).

Most international migrants come from poor semi-urban and rural communities, are male, typically between 18 and 35 years old, semi-literate, and either unskilled or semi-skilled workers. Women rarely migrate independently. In 2020 fewer than 2,000 women migrated internationally, primarily to Saudi Arabia, the United Arab Emirates and the United Kingdom (BEOE 2020). Since most international migrants leave alone, their prolonged absence affects family life significantly and creates economic inequalities and disparities in their communities of origin. Several push factors drive young people to risk the many dangers of irregular migration and human trafficking (UN DESA 2022).

Remittances from international migrants are one of the major sources of Pakistan’s economic growth. In 2017 remittances contributed 6.5 per cent of the country’s gross domestic product, in transactions worth more than USD 19.6 billion (IOM 2019). This increased to USD 29.4 billion in 2020–2021 (Rizvi 2021).

Pakistan is yet to sign or ratify the International Convention on the Protection of the Rights of All Migrant Workers and Members of their Families. Domestic legislation is therefore neither aligned with the protection of migrants’ human rights nor compliant with international human rights law and best practices on migration. These gaps include the persisting inability to guarantee the right to vote to Pakistan’s absent voters—its internal and international migrants.

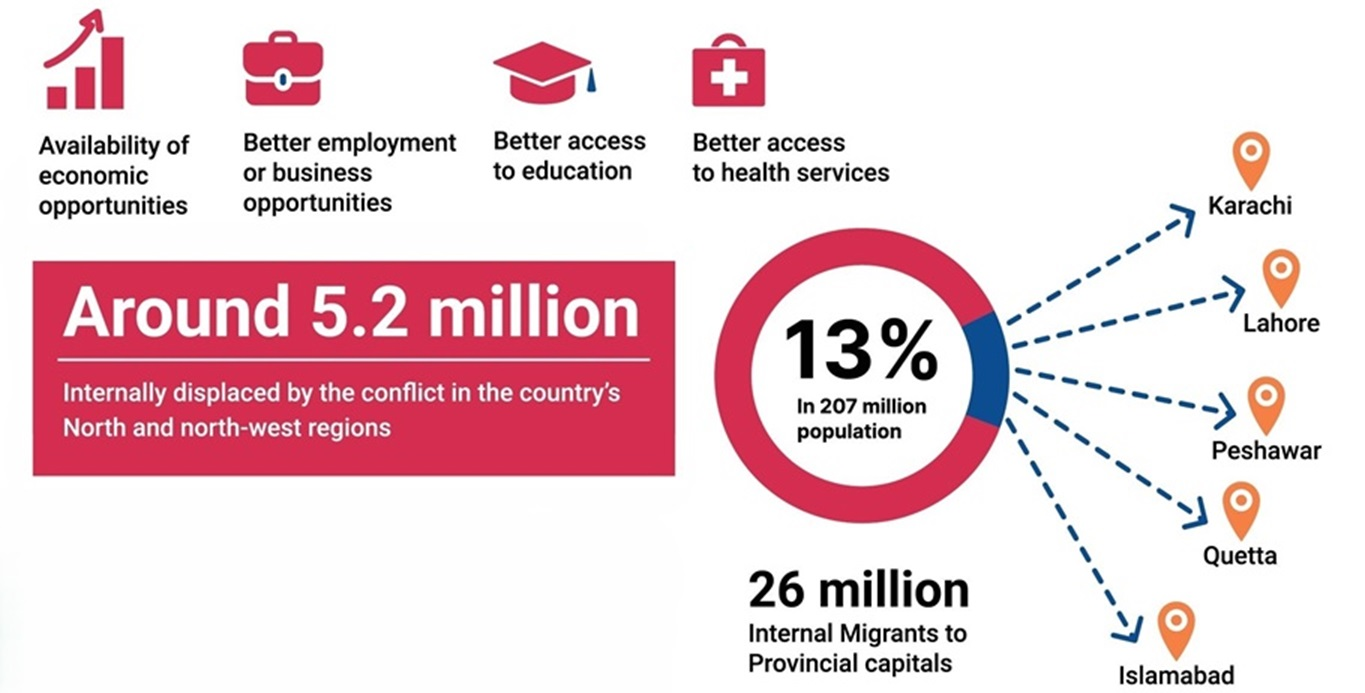

Internal migration in Pakistan is a significant phenomenon. Internal migration takes place mainly from rural to urban areas, through circular and permanent flows. The 2014–2015 Labour Force Survey by the Pakistan Bureau of Statistics (PBS) estimated that, at that time, 13 per cent of the population (26 million out of 207 million people) were internal migrants (PBS 2015). In 2019 over 26 million Pakistanis were estimated to have migrated internally and to be residing outside their place of birth (IOM 2019). Most internal migrants relocate to the major urban centres, mainly the provincial capitals, such as Karachi, Lahore, Peshawar and Quetta, and the federal capital, Islamabad (IOM 2019).

Since 2009 about 5.2 million citizens have been internally displaced by conflict in Pakistan’s north and north-west (Sayeed and Shah 2017). Additionally, a major 2005 earthquake left around 3.5 million people homeless, many of whom were moved to temporary shelters before resettlement (UN Habitat 2008). Most rural migrants relocate to slums or informal settlements in peri-urban and urban areas, where they face social integration challenges, poor access to basic services and income disparities. While urbanization trends support internal migration, unplanned growth leads to inadequate services and a declining quality of life in cities (Zahid 2023).

2. Drivers of migration within and outside Pakistan

Various push and pull factors lead to migration either within the country or abroad. These include the following:

- Economic conditions. Chronic poverty and scarce employment opportunities push many to migrate to the GCC countries, where demand for unskilled and semi-skilled workers is high. Highly skilled or literate workers migrate to Spain, the United Kingdom and the USA (Ishfaq et al. 2017).

- Climate change and natural disasters. Over the past two decades, Pakistan has been severely affected by the climate crisis and faced several natural disasters, including several droughts between 1999 and 2002, an earthquake in 2005 and floods in 2010.3 These have led to large-scale internal and international migration from the northern provinces and the Indus River Delta (Khosa 2014). Seasonal migration is linked to climate change–related issues, including extreme weather events, seasonal water shortages, and a lack of available fodder. Many individuals have migrated following natural hazards such as flooding, extreme snowfall, monsoon rains, bursting glaciers, earthquakes and droughts, or to avoid the risks associated with such disasters (Huang 2023).

- Conflict and war. Pakistan has experienced numerous internal conflicts since its independence in 1947. These include ethnic tensions, sectarian violence, and insurgencies (USIP 2023). Insecurity resulting from post-9/11 military operations in the Khyber Pakhtunkhwa province and Baluchistan forced communities in the former Federally Administrated Tribal Areas (FATA) to migrate internally (relocate to the Federal Capital Territory or to other large urban centres) or abroad (Ahmed 2012). Following the events of 11 September 2001, FATA became a haven for militants, leading to significant military interventions. These operations, while aimed at countering terrorism, caused substantial displacement among local populations (Gandhara 2019). Ethnic and religious violence against Shia Hazaras has also led to international migration, mainly to Australia. Over 20,000 asylum applications were filed in Australia in 2020, mainly because of political persecution (Mandokhail 2022).

- Lack of infrastructure and facilities. Pakistan’s rural areas frequently face significant deficiencies in essential services, including lack of healthcare, education (Gillani 2020), water, sanitation, gas, information technology and transportation infrastructure (Mukhtar 2024). Where such services are available, they are often grossly inadequate. Seeking better educational opportunities is an important factor in internal migration (Gazdar 2006). Internal migration is predominantly by young people between 15 and 24 years of age, who migrate to urban areas to pursue further study and better employment opportunities (Irfan 1986).

- Joining friends or family abroad. Finally, established Pakistani communities abroad, particularly in the United Kingdom, the USA and the GCC states, serve as a strong pull factor, as the presence of family and friends can ease integration and provide support (Pakistan Lawyer 2024).

3. Status of the electoral enfranchisement of Pakistan’s absent voters

The right to vote for those who are absent from their constituency or place of registration on election day, either within the country or abroad, has been a long-debated issue that continues to be unresolved in Pakistan.

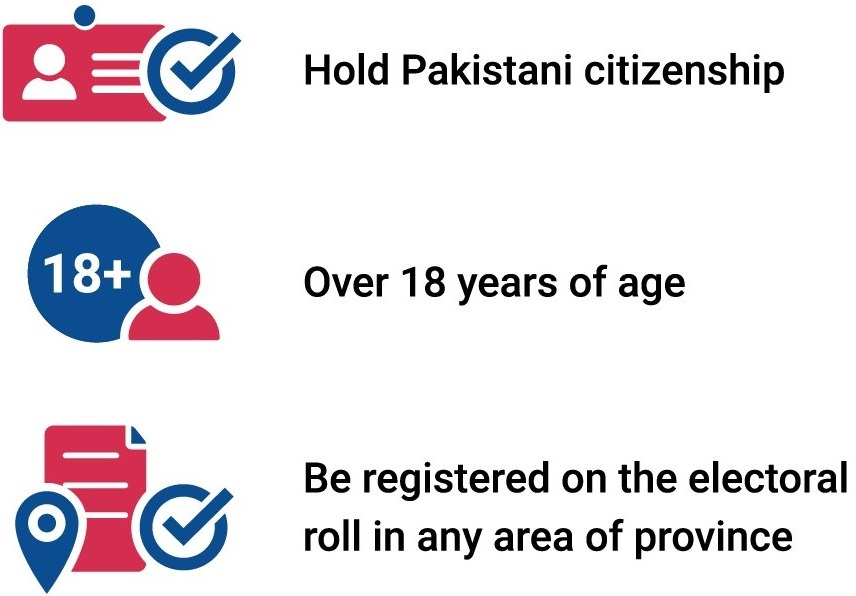

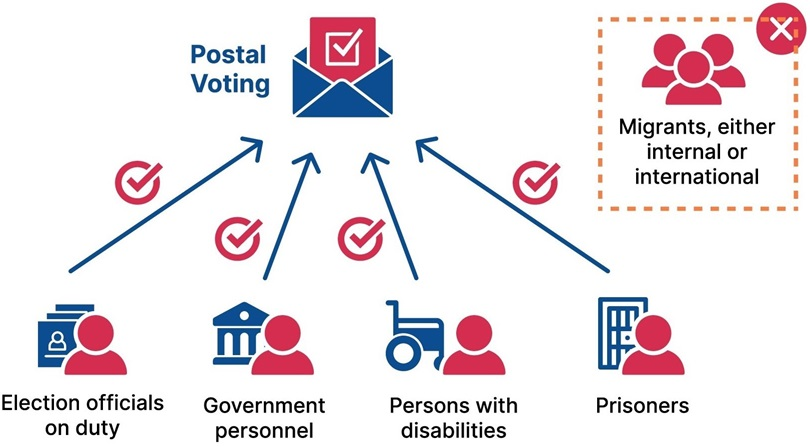

Article 106(2) of the Constitution of Pakistan establishes that to vote a person must hold Pakistani citizenship, be over 18 years of age, be registered on the electoral roll in any area of a province and not have been declared of unsound mind by a competent court. Typically, voting takes place in person at the assigned polling station on election day. However, exceptions are made in the 2017 Election Act (section 93) for some categories of absent voters to exercise their right to vote through postal voting. These categories are government personnel, election officials on duty, people with disabilities and prisoners. Migrants, either internal or international, are not one of these exceptions.

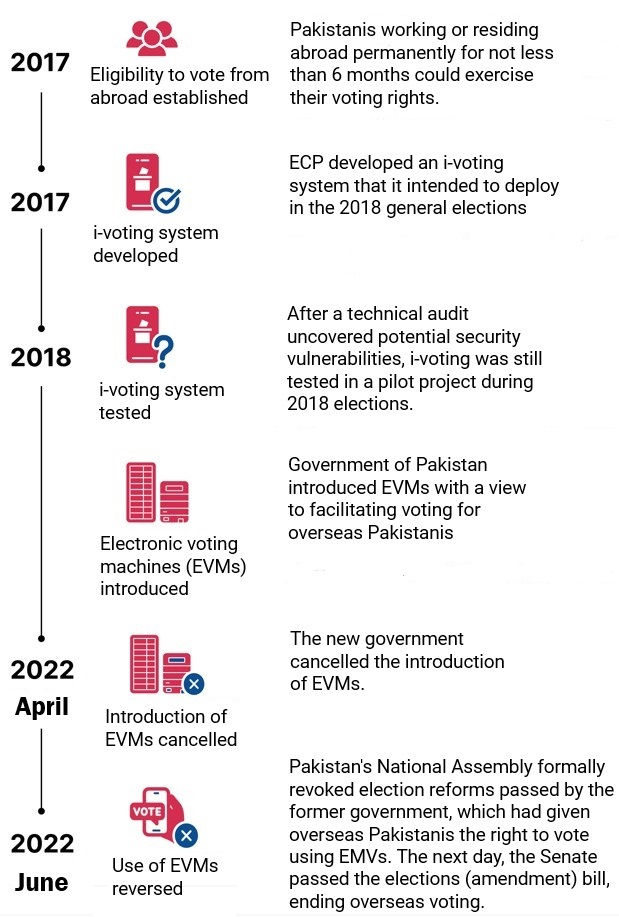

The earliest constitutional petition demanding the enfranchisement of overseas voters was filed in 1993. The Supreme Court of Pakistan referred the petition to the government and the ECP for consideration (Haq, McDermott and Ali 2019). After a hiatus of almost two decades, more petitions followed in 2011 and 2015, prompting the Supreme Court to rule that, as suffrage for absent voters cannot be denied on technical or operational feasibility grounds (Riaz 2018), the ECP had to adopt the necessary measures to enfranchise them. Section 94 of the 2017 Election Act established that the ECP, with the technical assistance of the National Database and Registration Authority (NADRA), and that of any other authority or agency, must ensure that Pakistanis working or residing abroad permanently or temporarily for not less than six months can exercise their right to vote in general elections in Pakistan.

However, the Parliament of Pakistan passed the elections (Amendment) Act, 2022, published in the official gazette on 22 June 2022. The Amendment Act reversed the mandatory use of EVMs in elections and substituted the section 94 and 103 of the Elections Act 2017 to provide ECP a discretionary power to conduct pilot projects for overseas Pakistani voting and use of EVMs and biometric verification system in the by-elections to assess its efficacy, secrecy, security and financial feasibility. The ECP was required to present a report to the Government of Pakistan on this assessment, which had to be laid before the parliament.

To comply with the new law, the ECP developed an i-Voting system that it intended to deploy in the 2018 general elections. Through this system, eligible voters would receive a unique secret code within a designated time frame before the election, which they would need to access the platform. The platform required multi-factor authentication for login, which combined the secret code with additional verification steps. Having entered the system, the platform would provide access to the ballot and candidate information, allowing voters to select a preferred candidate and confirm their vote electronically. The system encrypted the voter’s choice at the point of casting their ballot and throughout transmission to ensure ballot secrecy. Votes cast through i-Voting would be kept separate from physical ballots until the end of the voting period. They would then be decrypted and counted together in a transparent manner. Plans to fully deploy i-Voting in 2018 had to be deferred, however, after a technical audit uncovered potential security vulnerabilities. Nonetheless, i-Voting was still tested in a pilot project during 2018 by-elections (Haq, McDermott and Ali 2019).4

In 2021, the Pakistani Government introduced legislation to implement EVMs and extend voting rights to overseas Pakistanis. On 17 November 2021, a joint session of Parliament passed the Elections (Second Amendment) Bill, 2021, which authorized the use of EVMs in future elections and granted overseas Pakistanis the right to vote through i-Voting (Radio Pakistan 2021). The Ministry of Science and Technology sought to engage with civil society organizations and political parties by providing demonstrations of the EVMs, but the political parties failed to reach a consensus on their introduction for the 2023 general elections.

However, on 2 May 2022, the subsequent government repealed these provisions, abolishing the use of EVMs, citing feasibility and security concerns, and revoking the voting rights of overseas Pakistanis (Syed 2022).

The use of EVMs has been much debated in Pakistani politics over the past decade. The skills needed to operate the machines and their untested status led the new government to reconsider a countrywide launch. Some analysts and political commentators have argued that the cancellation of EVMs and the revocation of voting rights for overseas Pakistanis were politically motivated. They claim that these actions could have been intended to reduce the potential influence of overseas voters, who are perceived to largely support specific political parties (Chaudhry 2022). Questions remain regarding whether overseas voters will regain their right to vote, using either EVMs or other more established mechanisms.

4. Challenges for the electoral enfranchisement of Pakistan’s migrants

By virtue of being absent from their constituencies on election day, migrants who have moved either within or outside Pakistan are unable to cast a vote. The inability of millions of internal and international migrants to vote in absentia in their country’s elections reduces voter turnout and distorts levels of democratic inclusion and representation.

Pakistan has had a volatile history and has experienced frequent military coups. Its democracy struggles with weak democratic institutions that have failed to deliver stability or meet people’s needs and expectations. Allegations of electoral fraud and manipulation have been common, leading many Pakistanis to question the legitimacy of elections and the effectiveness of their democratic system (Anjum 2023).

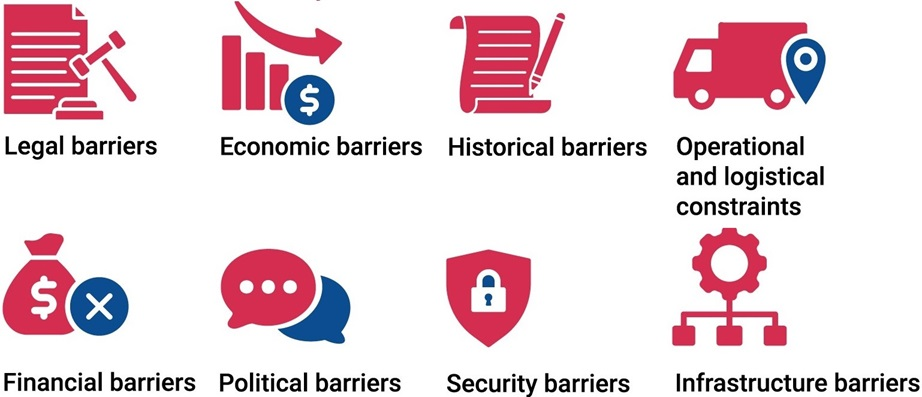

Several barriers prevent the adoption of a viable, sustainable and trusted system of voting to enfranchise Pakistan’s absent voters:

- Political barriers. The possible introduction of a system of absentee voting has been part of charged political discussions and debates leading up to electoral reform (Mackisack 2023). Many political parties have appealed to the superior courts to have the right to suffrage for overseas voters duly recognized and upheld (Nawaz 2022). Enfranchising Pakistan’s 7.6 million international migrants—an average of 28,500 per constituency—could have a considerable political impact on election results. Competition in the 2018 and 2024 general elections was tight in numerous constituencies,5 and candidates won with a margin6 of less than 10,000 votes (FAFEN 2018). This trend underscores the highly competitive nature of the electoral landscape, where even minor shifts in voter preference significantly influence outcomes. In such circumstances, absentee voting could likely have significant influence on the outcome of election.

- Legal barriers. The strict legal requirement for most eligible voters to cast their ballot in person at a polling station in their constituency of registration on election day remains an insurmountable impediment.

- Economic barriers. Most internal migrants do not have sufficient financial resources or the time to return to their constituencies of registration on election day to vote there. Polling stations are sometimes located significant distances apart, which makes it difficult even for voters living in the area to reach them to vote. This is especially the case in Baluchistan province (Malik 2023). International migrants are similarly expected to face a similar situation. It may be financially cumbersome for them to return to Pakistan to vote.

- Historical barriers. Traditionally, Pakistan’s legal framework has not favoured the inclusion of absent voters and made few exceptions to guarantee the enfranchisement of select categories of such voters. While the 2017 Election Act extended postal voting to persons with disabilities and prisoners, it ignored the opportunity to enfranchise internal and international migrants.

- Operational and logistical constraints. Pakistan is a vast geographical area, with around 1,100 national and provincial electoral constituencies, making it difficult for the ECP to deal with the introduction of a system for absentee voting. Regardless of the absentee voting system adopted, using either EVMs or i-Voting, the operational effort required to enfranchise 8 million overseas Pakistanis and 26 million internal migrants would be enormous.

- Financial barriers. The financial and human resources required to enable in-country absentee voting and out-of-country voting are not available. The annual budget for the overall operations of the ECP in the financial year 2021–2022 was PKR 5 billion (USD 28 million) (Ministry of Finance 2021). Designated to support the ECP’s mandate of overseeing and conducting free and fair elections across the country, this funding would not be sufficient to enfranchise millions of absent voters across the world.

- Security barriers. Insecurity linked to internal political instability, terrorism and ethnic or tribal conflicts has forced many Pakistanis to relocate. Large numbers of refugees are unable to return to their places of origin, resettle or vote (USIP 2023). Even though many of these internal migrants and displaced people were forced to move a long time ago, they still maintain a close ethnic, cultural, economic and political affiliation with their places of origin (Mehdi 2000). They are therefore unwilling to register to vote in the constituency of their current residence (Malik 2023).

- Infrastructure barriers. Pakistan’s limited technology-based infrastructure would need a major upgrade to sustain the nationwide introduction of an online or electronic voting system that could enable migrants to vote and guarantee its transparency and security.

5. Prospects for the electoral enfranchisement of Pakistan’s migrants

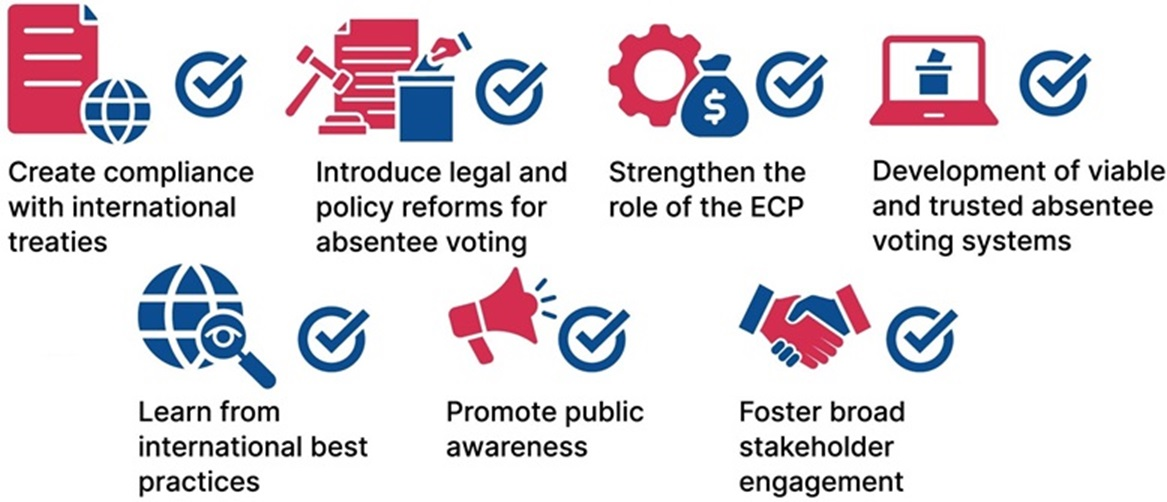

Pakistan has the potential to make its democracy more inclusive, participatory and representative by guaranteeing the right to vote to its large disenfranchised absent voter population. Prospects to move in this direction include the following:

- ensuring greater compliance of election legislation with international treaties, laws and best practices that protect the political rights of migrants and their families;

- developing and adopting legal and policy reforms for the electoral enfranchisement of Pakistan’s absent voters, enabling absent voters to vote from their current location by removing the requirement to be physically present in their constituency of registration on election day;

- strengthening the role of the ECP in undertaking such a large-scale and complex endeavour by providing the commission with the necessary mandate and financial resources, strengthening its operational capacity and expanding the capacities of its Directorate of Overseas Pakistanis;

- devising the most suitable, reliable, secure, cost-effective and trusted system of absentee voting for Pakistan, using EVMs, i-Voting or one or more other absentee voting methods, which would need to be sustained, maintained and gradually refined over multiple election cycles;

- researching and learning from best international practices and the voting methods used to enfranchise absent voters and using the resulting knowledge to consider and broadly debate the most suitable options for enfranchising Pakistan’s absent voters;

- promoting public awareness of any absentee voting methods introduced to enfranchise Pakistan’s absent voters; and

- fostering broader and more effective stakeholder engagement: first, by advocating for the necessary legal and policy reforms, and then, once these reforms have been introduced, by engaging key political and electoral stakeholders7 in consensus-seeking discussions leading to the adoption, design and implementation of an absentee voting system that is agreed and trusted by all.

The enfranchisement of Pakistan’s absent voters is a long-debated and politically controversial issue that remains unresolved. Ultimately, the viability of any of the above-mentioned options is heavily reliant on the existence of strong and genuine political will. It is only through compromise, political will and consensus that this much-needed reform could become a reality, allowing Pakistan’s democracy to become as truly inclusive, participatory and representative as it should aim to be.

Abbreviations

BEOE Bureau of Emigration & Overseas Employment

ECP Election Commission of Pakistan

EVM Electronic voting machine

FATA Federally Administrated Tribal Areas

GCC Gulf Cooperation Council

NDARA National Database and Registration Authority

PKR Pakistani rupees

References

Ahmed, Z., S., ‘Pakistan: Challenges of conflict-induced displacement’, Peace Insight, 23 March 2012, <https://www.peaceinsight.org/en/articles/pakistan-the-challenges-of-conflict-induced-displacement-of-people/?location=pakistan&theme=development&>, accessed 18 November 2024

Ali, G., Akhtar, R. and Ali, A., ‘Return migration and re-integration challenges in high mountain regions in Pakistan’, GeoJourna, 88 (2023), pp. 5247–58,<https://doi.org/10.1007/s10708-023-10919-1>

Anjum, A., ‘Is democracy responsible for Pakistan’s turmoil’, The Express Tribune, 16 October 2023, <https://tribune.com.pk/story/2441334/is-democracy-responsible-for-pakistans-turmoil>, accessed 17 November 2024

Biswas, B., ‘‘‘You can’t go to war over refugees’’: The Bangladesh war of 1971 and the international refugee regime’, Refugee Survey Quarterly, 42/1 (2023), pp. 103–21, <https://doi.org/10.1093/rsq/hdac026>

Bureau of Emigration & Overseas Employment (BEOE), ‘Labour Migration Report 2020’, Government of Pakistan (2020), <https://beoe.gov.pk/files/statistics/yearly-reports/2020/2020-full.pdf>, accessed 10 November 2024

Bukhari, A., ‘Hope and hardship in Karachi’s Bengali enclave’, T-Magazine, The Tribune, 19 November 2023, <https://tribune.com.pk/story/2447112/hope-and-hardship-in-karachis-bengali-enclave>, accessed 10 November 2024

Chaudhry, F., ‘NA approves bill to deprive overseas Pakistanis from voting, stop use of EVMs in general election’, The Dawn, 26 May 2022, <https://www.dawn.com/news/1691588>, accessed 11 November 2024

Free & Fair Election Network (FAFEN), ‘FAFEN Election Observation Report: 1.67 Million Ballots Excluded from the Count’, 3 August 2018, <https://fafen.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/08/FAFEN-Report-Margin-of-Victor-Less-than-Rejected-Ballots-General-Election-2018.pdf>, accessed 11 November 2024

Gandhara, ‘As death toll rises, Pashtun lawmaker calls for Waziristan protest’, Gandhara, RadioFreeEurope/RadioLiberty, 27 May 2019, <https://gandhara.rferl.org/a/pakistan-as-death-toll-rises-pashtun-lawmaker-calls-for-waziristan-protest/29965861.html>, accessed 17 November 2024

Gazdar, H., ‘Karachi, Pakistan: Between regulation and regulation’, in M. Balbo (ed.), International Migrants and the City (Nairobi: United Nations Human Settlements Programme, 2006), <https://unhabitat.org/international-migrants-and-the-city>, accessed 15 November 2024

Gillani, W., ‘Lack of access to healthcare’, Special Report, The News On Sunday, 11 October 2020, <https://www.thenews.com.pk/tns/detail/726878-lack-of-access-to-healthcare/>, accessed 16 November 2024

Haq, H. B., McDermott, R. and Ali, S. T., ‘Pakistan’s Internet voting experiment’, 10 July 2019, arXiv, <https://arxiv.org/pdf/1907.07765.pdf>, accessed 4 November 2022

Huang, L., ‘Climate Migration 101: An Explainer’, Migration Policy Institute, 16 November 2023, <https://reliefweb.int/report/pakistan/climate-migration-101-explainer/>, accessed 17 November 2024

Hussain, K. and Khan, M., ‘From Refugees to Citizens–A Report on Integration from Dhaka, Bangladesh’, RIT Case Report, The Fletcher School of Law and Diplomacy, Tufts University, 17 March 2023, <https://sites.tufts.edu/ihs/rit-case-report-from-refugees-to-citizens-a-report-on-integration-from-dhaka-bangladesh/>, accessed 20 November 2024

Imarat Institute of Policy Studies (IIPS), ‘Pakistani Diaspora’, Iqbal Blogs, 21 May 2021, <https://iips.com.pk/pakistani-diaspora/>, accessed 13 November 2024

International Organization for Migration (IOM), Pakistan Migrant Snapshot: August 2019 (Bangkok: IOM, 2019), <https://migration.iom.int/sites/g/files/tmzbdl1461/files/reports/Pakistan%20Migration%20Snapshot%20Final.pdf>, accessed 4 November 2024

—, World Migration Report 2022 (Geneva: IOM, 2021), <https://publications.iom.int/books/world-migration-report-2022>, accessed 6 November 2024

Irfan, M., ‘Migration and development in Pakistan: Some selected issues’, The Pakistan Development Review, 25/4 (1986), pp. 743–55, <http://www.jstor.org/stable/41258789>, accessed 20 November 2024

Ishfaq, S., Ahmed, V., Hassan, D. and Javed, A., ‘Internal migration and labour mobility in Pakistan’, in S. Irudaya Rajan (ed.), South Asia Migration Report 2017 (Routledge, 2017)

Khosa, S., ‘Re-development, recovery and mitigation after the 2010 catastrophic floods: The Pakistani experience’, in N. Kapucu and K. Liou (eds) Disaster and Development: Examining Global Issues and Cases, Environmental Hazards (Cham, Switzerland: Springer, 2014), <https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-04468-2_21>

Kulik, R. M., ‘Partition of India, South Asian history [1947]’, The Encyclopaedia Britannica, last updated, 25 October 2024, <https://www.britannica.com/event/Partition-of-India>, accessed 19 November 2024

F. Laczko and M. L. McAuliffe (eds), Migrant Smuggling Data and Research: A Global Review of the Emerging Evidence Base (Geneva: International Organization for Migration, 2016), <https://publications.iom.int/books/migrant-smuggling-data-and-research-global-review-emerging-evidence-base>, accessed 10 November 2024

Mackisack, D., ‘There and back again – the story of Pakistan’s brief experiment with electronic voting’, Democracy Technologies, 8 December 2023, <https://democracy-technologies.org/voting/there-and-back-again-the-story-of-pakistans-brief-experiment-with-electronic-voting/>, accessed 19 November 2024

Malik, M., ‘The political incorporation of rural-to-urban migrants in Karachi, Pakistan’, International Growth Centre (IGC), 30 September 2023, <https://www.theigc.org/collections/political-incorporation-rural-urban-migrants-karachi-pakistan>, accessed 12 November 2024

Mandokhail, R., ‘Uncertain futures ahead for Hazara youth’, T-Magazine, The Tribune, 13 February 2022, <https://tribune.com.pk/story/2343241/uncertain-futures-ahead-for-hazara-youth>, accessed 17 November 2024

Maryam, H., ’Stateless and helpless: The plight of ethnic Bengalis in Pakistan’, Aljazeera, 29 September 2021, <https://www.aljazeera.com/features/2021/9/29/stateless-ethnic-bengalis-pakistan>, accessed 11 November 2024

Mehdi, S. S., ‘Internal displacement in Pakistan’, Refugee Survey Quarterly19/2, (2000), pp. 89–100, <http://www.jstor.org/stable/45053233>, accessed 21 November 2024

Ministry of Finance, ‘Federal Budget 2021-22’, Finance Division, Government of Pakistan, 20–21, <https://www.finance.gov.pk/budget/Budget_2021_22/6_Budget_in_Brief_English_2021_22.pdf>, accessed 8 November 2024

Mughal, B. K. and Naqvi, Z., ‘Bengalis of Karachi demand urgent resolution to identity problem’, The Dawn, 16 June 2018, <https://www.dawn.com/news/1414503>, accessed 9 November 2024

Mukthar, I., ‘Pakistan’s rural infrastructure is inadequate’, Development and Cooperation (D+C), 8 November 2024, <https://www.dandc.eu/en/article/rural-communities-generally-lack-good-public-services-and-have-too-few-economic>, accessed 21 November 2024

Nawaz, M., ‘Voting rights to overseas Pakistanis: Imran Khan moves SC against amendments in election laws’, The News, 4 July 2022, <https://www.thenews.com.pk/latest/971374-imran-approaches-sc-after-govt-deprives-overseas-pakistanis-of-voting-rights>, accessed 12 November 2024

Pakistan Bureau of Statistics (PBS), ‘Labour Force Survey 2014-15, Thirty Third Issue, Statistics Division, November 2015, <https://www.pbs.gov.pk/publication/labour-force-survey-2014-15-annual-report>, accessed 12 November 2024

Pakistan Lawyer, ‘Exploring immigration trends: Pakistan’s diaspora and impact’, Immigration, 2 November 2024, <https://articles.pakistanlawyer.com/2024/11/02/exploring-immigration-trends-pakistans-diaspora-and-impact>, accessed 20 November 2024

Radio Pakistan, ‘Parliament passes bills for use of EVMs in elections, right of vote to overseas Pakistanis’, 17 November 2021, <https://www.radio.gov.pk/17-11-2021/joint-sitting-of-parliament-passes-bill-granting-right-of-vote-to-overseas-pakistanis-providing-for-use-of-evms-in-elections>, accessed 17 November 2024

Riaz, A., ‘Overseas Pakistanis get right to vote’, The News, 18 August 2018, <https://www.thenews.com.pk/print/356590-overseas-pakistanis-get-right-to-vote>, accessed 10 November 2024

Riggs, E. P. and Jat, Z. R., ‘The 1947 partition of India and Pakistan: Migration, material landscapes, and the making of nations’, Journal of Contemporary Archaeology, 3/2 (2016), pp. 139–46, <https://doi.org/10.1558/jca.31805>

Rizvi, M., ‘Pakistan receives record $29.4 billion remittances in 2021’, Khaleej Times, 15 July 2021, <https://www.khaleejtimes.com/asia/pakistan-receives-record-29-4-billion-remittances-in-2021>, accessed 4 November 2022

Rahman, B., ‘Indo-Bangladesh Standoff’, South Asia Analysis Group,

Sarkar, S., ‘Treatment of the 1971 East Bengali refugees: A forgotten experience’, The Times of India, 19 December 2021, <https://timesofindia.indiatimes.com/blogs/sarkari-thoughts/treatment-of-the-1971-east-bengali-refugees-a-forgotten-experience/>, accessed 10 November 2024

Sarwar, H., ‘Pakistani diaspora’s dynamic role in building national identity and profile’, World Affairs Insider, 8 October 2023, <https://worldaffairsinsider.com/pakistani-diasporas-dynamic-role-in-building-national-identity-and-profile/>, accessed 11 November 2024

Sayeed, S. and Shah, R., ‘Displacement, Repatriation and Rehabilitation: Stories of Dispossession from Pakistan’s Frontier’, Working Paper, Stiftung Wissenschaft und Politik, German Institute for International and Security Affairs, Berlin, 2017, <https://www.swp-berlin.org/publications/products/arbeitspapiere/Sayeed_and_Shah_2017_Internal_Displacement_Pakistan.pdf>, accessed 11 November 2024

Syed, R., ‘Govt abolishes use of EVMs and voting right of overseas Pakistanis’, ProPakistani, 26 May 2022, <https://propakistani.pk/2022/05/26/govt-abolishes-use-of-evms-and-voting-right-of-overseas-pakistanis/?utm>, accessed 10 November 2024

United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs (UN DESA), ‘Migration Trends and Families’, Policy Brief No. 133, 11 May 2022, <https://www.un.org/development/desa/dpad/wp-content/uploads/sites/45/publication/PB_133.pdf>, accessed 10 November 2024

United Nations Human Settlements Programme (UN Habitat), ‘Pakistan - 2005 – Earthquake’, B.16, Shelter Projects, 2008, <https://shelterprojects.org/shelterprojects2009/ref/B.16-Pakistan-2005-Earthquake.pdf>, accessed 9 November 2024

United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC), ‘Human Trafficking and Migrants Smuggling Routes from Pakistan to Neighboring and Distant Countries’, UNODC Country Office Pakistan, Report, October 2012, <https://www.unodc.org/documents/pakistan/201211_Survey_on_Human_Trafficking_and_Migrant_Smuggling_Routes_Edit1_FINAL.pdf>, accessed 15 November 2024

United States Institute of Peace (USIP), ‘The Current Situation in Pakistan’, USIP Fact Sheet, 23 January 2023, <https://www.usip.org/publications/2023/01/current-situation-pakistan?utm>, accessed 17 November 2024

World Bank Group, ‘Net Migration – Pakistan’, Data, United Nations Population Division, World Population Prospects: 2022 Revision, <https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/SM.POP.NETM?locations=PK>, accessed 17 November 2024

Zahid, R., ‘Rural–Urban Migration: Causes, Consequences, and Solutions’, Imarat Institute of Policy Studies (IIPS), Iqbal Blogs, 31 July 2023, <https://iips.com.pk/rural-urban-migration-causes-consequences-and-solutions/>, accessed 10 November 2024

About the author

Ali Imran is a seasoned expert in democratic governance with over 23 years of experience in national, international public and private sector development organizations. His expertise spans key areas such as elections, parliamentary strengthening, effective democratic governance, gender equality and human rights protection.

With a Master’s degree in Political Science and a Bachelor’s degree in Law (LLB), Imran has worked extensively with parliamentary institutions across Asia, the EU, MENA region, Pakistan and the UK. From 2013 to 2017, he served as the Country Representative for the Westminster Foundation for Democracy (UK), where he played a pivotal role in enhancing parliamentary performance in Pakistan.

He has been associated as a Senior Expert for the Club de Madrid in Pakistan, where he contributed to Shared Societies Project, an initiative focused on the inclusive and participatory development of marginalized communities. He was a part of the Asia Foundation’s Strengthening Transparency and Accountability in Electoral Processes in Pakistan programme in 2012–2013, where he managed political parties’ capacity-building and compliance with the Code of Conduct for 2013 elections.

In his previous roles, he has worked on human rights and women’s empowerment with prestigious organizations such as the Civil Services Academy, Medecins du Monde, Aurat Foundation, UNFPA, Oxfam Novib and AGHS Legal Aid Cell.

About this series

This case study is part of the ‘Absent Voters of South Asia’ project, which falls under the project of ‘Migrations and Elections’ that covers member states of the South Asian Council for Regional Cooperation (SAARC), such as Afghanistan, Bangladesh, Bhutan, India, the Maldives, Nepal, Pakistan and Sri Lanka.

- Particularly in Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates.

- Bahrain, Kuwait, Oman, Qatar, Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates.

- Approximately one-fifth of Pakistan’s total land area was affected by floods, with the Khyber Pakhtunkhwa province facing the brunt of the damage and casualties.

- A total of 7,538 votes were cast through i-Voting and incorporated into the final by-election results.

- Currently, there are a total of 342 seats in Pakistan’s National Assembly. Of these, 266 are filled by direct elections.

- According to the Free and Fair Election Network (FAFEN), in the 2018 general elections, 79 National Assembly constituencies had victory margins under 10,000 votes.

- Key stakeholders are numerous and would include the parliament, political parties, NADRA, the Overseas Pakistanis Foundation, the Ministry of Overseas Pakistanis and Human Resource Development, the Bureau of Statistics, the Ministry of Law and Justice, the Ministry of Human Rights, the BEOE, the Ministry of the Interior, domestic election observation groups, local civil society organizations, the media and migrant workers’ organizations. Greater cooperation between the ECP and NADRA, the BEOE, the Bureau of Statistics and the Labour Force Survey would also be key for more accurate mapping of the number and location of internal and international migrants.

© 2024 International Institute for Democracy and Electoral Assistance

International IDEA publications are independent of specific national or political interests. Views expressed in this publication do not necessarily represent the views of International IDEA, its Board or its Council members.

With the exception of any third-party images and photos, the electronic version of this publication is available under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 (CC BY-NC-SA 4.0) licence. You are free to copy, distribute and transmit the publication as well as to remix and adapt it, provided it is only for non-commercial purposes, that you appropriately attribute the publication, and that you distribute it under an identical licence. For more information visit the Creative Commons website: <http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/4.0>.

Design and layout: International IDEA

DOI: <https://doi.org/10.31752/idea.2024.104>

ISBN: 978-91-7671-857-5 (PDF)

ISBN: 978-91-7671-924-4 (HTML)