The Absent Voters of Nepal

Challenges and Prospects for the Enfranchisement of Migrants

Introduction

This case study explores the complexities surrounding the enfranchisement of Nepal’s internal and international migrant population. Despite its large migration flows—particularly those related to its temporary workers—Nepal’s migrants continue to be denied their right to vote.

The study outlines legal, constitutional and operational challenges—such as citizenship restrictions, voter registration complexities, limited voter awareness, the lack of an adequate enabling infrastructure, logistical hurdles, financial constraints and the need for a broad political consensus—that so far have made the adoption of a viable absentee voting system impossible. It then highlights how, despite numerous ongoing discussions and assessments, no concrete progress has been made.

In its conclusions, the study emphasizes that enfranchising Nepal’s absent voters—both those who have migrated abroad and those moving within the country—depends on several critical preconditions being met: these include the necessity for meaningful consultations leading to broad political consensus and legal reform, alongside effective communication and an increased electoral budget. These steps could facilitate a phased introduction of a viable, sustainable and trusted absentee voting system. By meeting these multifaceted conditions, Nepal could ensure that its absent voters are finally guaranteed their voting rights.

1. Nepal’s migration: Background and characteristics

Nepal’s migration patterns can be traced to a complex interplay of historical, geopolitical, economic, socio-cultural and environmental factors that continue to shape the nation’s demographic landscape. Its diverse ethnic and cultural landscape comprising over 120 ethnic groups has contributed to a dynamic history of both internal and international migratory movements.

Various factors have helped to shape Nepal’s migration in the modern era. Historically, labour migration to neighbouring countries such as India has been a major driver (Adhikari et al. 2023). Migration between India and Nepal is thought to have begun in ancient times, but the recruitment of Nepali Gurkhas by the East India Company in 1815 began large-scale, formal migration to India (Kumar 2022).1 Over the years, more and more Nepalese were drafted into the British and Indian armies, and young people began to migrate abroad for employment purposes. The Peace and Friendship Treaty signed by India and Nepal in 1950 provided for free movement for India’s and Nepal’s citizens across the respective borders and entitled them to equal treatment on a reciprocal basis (Government of India 1950).2 The social, cultural, political, linguistic and other ties that exist between the two nations have also made it easier for people to move between the two countries (Shukla 2006). More recently, the Maoist insurgency of 1996–2006 led to widespread violence and political instability, inducing many Nepalis to relocate within the country or abroad (OHCHR 2012).

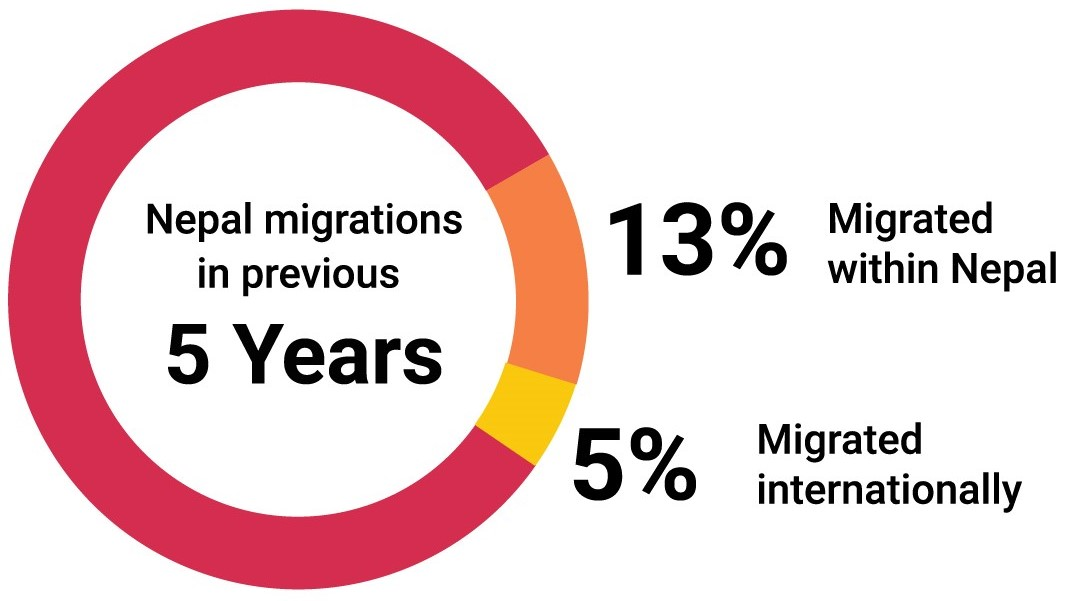

Both internal and international migration are becoming increasingly important livelihood strategies in Nepal (IOM 2018). However, internal migratory movements are estimated to be substantially higher than international ones. The 2011 National Population and Housing Census estimated that approximately 13 per cent of the population had relocated within Nepal in the previous five years, while 5 per cent had migrated internationally (National Planning Commission 2012). A few years later, in 2014, Nepal’s Central Bureau of Statistics (CBS) determined that at least 15 per cent of the country’s population was residing outside of their district of origin (CBS 2014).

In recent years, Nepal has experienced a steady pattern of internal migration from the hilly and mountainous regions to the Terai, the lowland region of southern Nepal, pulled by the prospects of better employment and educational opportunities and improved living conditions. Migrants from these regions account for three-quarters of the country’s internal migration. Some districts have recorded outflows higher than 50 per cent of their population (Clewett 2015).

Until recently, Nepal’s internal migration had not led to the urbanization processes experienced in other countries, as it was predominantly characterized as rural-to-rural or seasonal movement, as farmers sought employment in towns during the agricultural off-season. This trend has changed in recent years, however, as rural-to-urban migration has increased significantly. Circular migrants move from rural to urban areas, normally on a temporary basis, typically for a maximum period of six months, based on seasonal labour requirements. Economic disparities and limited employment opportunities are the main factors pushing Nepalis to migrate internally from rural to urban areas, while better living conditions, better education and health facilities, higher incomes and higher living standards constitute the pull factors (KC 2020).

In addition to economic factors, Nepal’s rural–urban internal migration is also influenced by social and cultural variables (Gurung 2012). Traditional values are considerably stronger in rural regions, and individualism is not considered favourably. People in urban areas, by contrast, enjoy more individual freedom to pursue modern ideas and lifestyles without constraints, making cities more attractive to the young people who are most likely to migrate there (NGLearn 2023).

Nepal is also characterized by internal displacement, either caused by environmental factors such as earthquakes, landslides and floods, or induced by conflict and political instability. Both factors have forced communities to relocate internally in search of safer living conditions (UNHCR 2016).

International migration is an important driver of Nepal’s economic and social development. Social and economic disparities and limited employment and educational opportunities push individuals and families to seek better prospects abroad. International migration is key for many households, and is often their only possible source of income (IOM 2023).

While the size of Nepal’s international migrant stock is difficult to estimate precisely and varies depending on the sources, statistics from Nepal’s Department of Foreign Employment—the government agency responsible for regulating foreign employment and overseeing the treatment of the country’s migrant workers—indicate that in 2019 more than 5.6 million of the country’s total population of 29 million were working abroad (Adhikari et al. 2023). This means that, at that time, one Nepali citizen in every five was an international migrant worker.

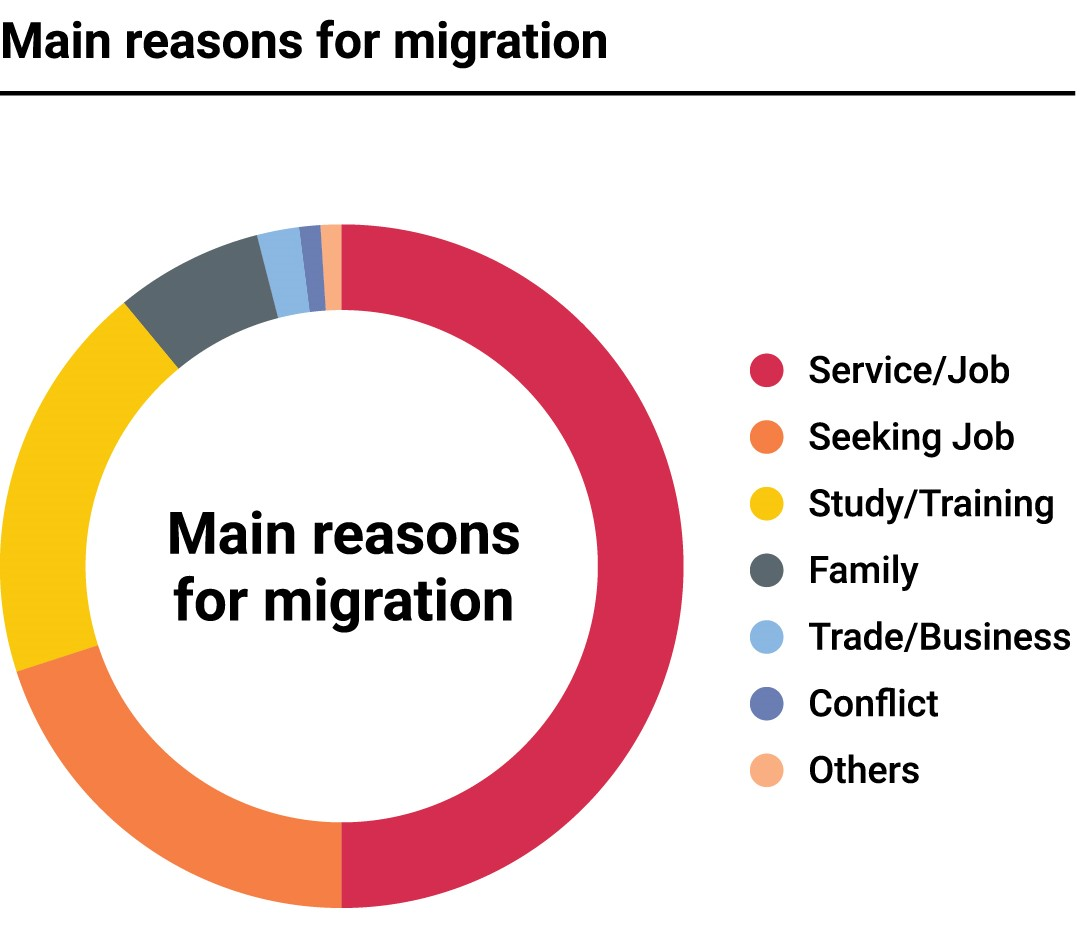

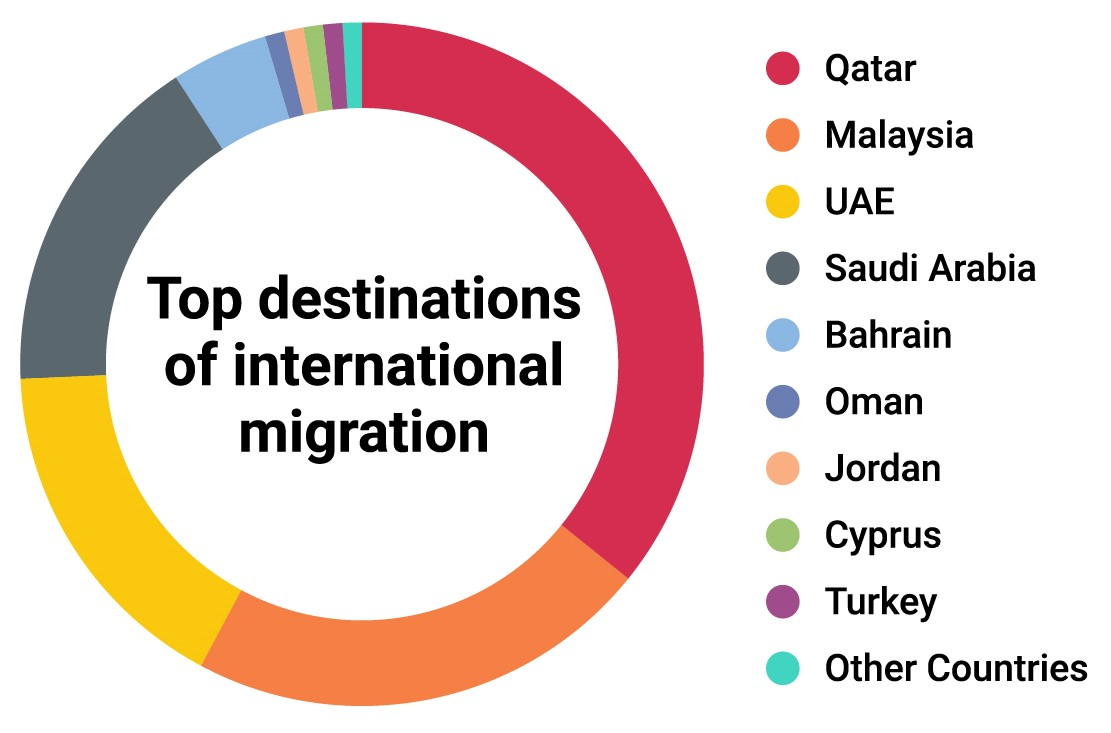

Before 1990 Nepalis migrated predominantly to India for employment reasons. While migration to India is still important, it is now complemented by temporary foreign employment in the Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) states, as well as migration to Malaysia, with which Nepal has a bilateral labour agreement (Pokharel 2020). In the period 2015–2019, Qatar was the most popular destination for Nepali migrants (32 per cent), followed by Malaysia (24 per cent), Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates (UAE) (17 per cent each) (Adhikari et al. 2023). Another route involves migration to developed countries such as Australia, Canada, Japan, South Korea, the United Kingdom and the United States as well as many European countries. While this migration stream is still small, it is growing fast (Adhikari et al. 2023). After Australia, Japan is the second most popular destination for Nepali students in higher education (Nepali Sansar 2019).

Labour migration by Nepalese youth is extensive and male-dominated. Terai is the region with the highest rate of labour migration. Labour migration on the part of women occurs mostly within Nepal, whereas labour migration on the part of men is more international (Sherpa 2010).

Despite its large internal and international migratory movements, currently Nepal does not extend the electoral franchise to its populations on the move. For Nepal, like for many other countries in South Asia, balancing the choice to extend voting rights to migrants with the need to preserve the integrity of its electoral processes continues to be a challenge.

Voting eligibility is guided by Nepal’s legal and constitutional framework, which includes the Constitution of Nepal, the Citizenship Act, electoral laws and regulations, the decisions of the Election Commission of Nepal (ECN) and court decisions. These sources set out the main requirements for qualifying to vote in Nepal. Accordingly, a voter must (a) be a citizen of Nepal; (b) have attained 18 years of age on the day of the election; and (c) have a permanent residence in a ward in any village development committee or municipality in any electoral constituency. Two of these requirements—(a) and (c) above—exclude Nepal’s international migrants from the electoral franchise.

The issue of citizenship for international migrants is complex and has been a subject of protracted debate and reform efforts. Discussions and efforts to extend voting rights to international and internal migrants have been ongoing in Nepal for more than a decade. Aware of the large numbers of voters disenfranchised both within and beyond its borders, the government and political parties have long discussed potential reforms to allow their absent voters to participate in elections. Such discussions and efforts prompted the ECN to assess the feasibility of alternative absentee voting options. Several assessments took place in the period 2012–2014. The ECN looked at the early and absentee voting systems adopted by Thailand. In addition, an out-of-country voting (OCV) Working Group looked at the possibility of establishing an OCV system, recommending the registration of voters residing overseas and broad consultations with political parties, civil society and the public to guide the adoption of such a system. The ECN conducted a third assessment in Bahrain, Kuwait, Qatar, Saudi Arabia and the UAE. The ECN understood the challenges involved in registering and allowing Nepali citizens to vote abroad, and the resulting OCV report outlined its feasibility (Out of Country Voting Working Group 2019).

In 2018, as the various debates and assessments had produced no concrete outcomes, the Supreme Court, acting on public interest litigation filed by the Law and Policy Forum for Social Justice, issued a directive to the Office of the Prime Minister and the Council of Ministers, the Ministry of Foreign Affairs and the ECN (The Himalayan Times 2018). The Supreme Court’s directive recommended extending the right to vote to all those who had neither rescinded their citizenship nor become citizens of another country, were at least 18 years of age, held a voter identity card and were registered with the relevant diplomatic mission (Pradhan 2018). Despite the Supreme Court’s directive, however, no laws were enacted or amended to allow the introduction of OCV for the 2022 general elections.

Until 2023, Nepal’s legislation—which distinguished between residents and non-resident Nepalis (NRNs)—did not recognize dual citizenship. A significant development occurred on 31 May 2023, when President Ramchandra Paudel ratified the Nepal Citizenship (First Amendment) Bill, 2079. This amendment allows children of parents who acquired citizenship by birth to obtain citizenship by descent, addressing the statelessness of many individuals (Ahmad 2023). The amendment permits NRNs to acquire citizenship3, except for those NRNs residing within South Asia. This provision aims to strengthen ties with the Nepali diaspora and acknowledge their contributions to the nation’s development (South Asia Time 2023). However, despite these reforms, challenges persist as, while NRNs are granted citizenship, it comes without political rights such as voting or holding public office.

As election legislation continues to require that eligible citizens cast their votes at their official place of residence, making no provision for OCV, international migrants are therefore denied the right to vote (Kamat 2022). Furthermore, as no forms of absentee, inter- or intra-constituency voting are available, internal migrants outside their constituency of registration on election day are also unable to vote (Taylor 2022). The enfranchisement of Nepal’s absent voters continues to be discussed today.

3. Challenges to the electoral enfranchisement of migrants in Nepal

The adoption of measures to extend voting rights to Nepal’s absent voters faces several challenges. These include the following:

- Lack of legislation regulating OCV or in-country absentee voting. Existing legislation limits the vote to citizens at their official place of residence or registration. International migrants are not considered citizens while residing outside of Nepal and are therefore denied their right to vote.

- Lack of political commitment and consensus. The adoption of a viable absentee voting system to enfranchise Nepal’s international and internal migrants would require significant changes to policy and to legal and procedural frameworks. These changes, in turn, remain impossible without a strong political commitment from the government and a broad consensus among mainstream political parties, which have been difficult to achieve due to several concerns about the possibility that OCV could influence the outcome of elections at home, about the risks that absentee voting might pose to the integrity of the electoral process and about the logistical, operational and financial implications of conducting elections in countries where Nepal lacks jurisdictional capacity or where operations are more difficult to run.

- Voter registration complexities. Voter registration is implemented using a computerized biometric system introduced in 2010. In addition to personal information, this system captures the registrant’s photograph and fingerprints, a procedure that requires a voter’s physical presence at the voter registration facility. Thus, by virtue of being absent, international migrants are unable to register and vote.

- Limited voting access. As numerous internal migrants reside at long distances from their constituency of registration, without any provisions for inter- or intra-constituency voting in place, they are no longer allowed to vote at their current places of residence. The residence requirement also continues to disenfranchise those on electoral duty, including polling station staff, security forces and domestic election observers, who, on election day, are often deployed away from their constituency of registration.

- Voter awareness and education needs. As many of Nepal’s international migrants have limited access to information about the electoral process, voter awareness and education needs would be immense. Nepal’s international migrants are dispersed across the world and reaching them worldwide with voting information and education would be a task of massive proportions, presenting numerous operational and financial difficulties.

- Limited infrastructure. Nepal has only limited infrastructure that could support the introduction of an OCV or inter-/intra-constituency absentee voting system. Introducing an OCV system allowing Nepali international migrants to vote in person at diplomatic missions in foreign jurisdictions would involve significant staffing requirements which would be difficult to for such missions to meet on their own. Additional complexities include that OCV would most likely require the deployment of ECN staff to support in-person OCV operations all over the world, as well as the conclusion of agreements with the numerous host countries where Nepali migrants reside.

- Logistical and operational complexities. Establishing an OCV system allowing Nepali international migrants to cast their votes in diplomatic missions would also likely pose significant logistical and operational challenges (OnlineKhabar 2019), not least the need to produce and dispatch sensitive and non-sensitive election materials, and deploy and train the required personnel.

- Risks to electoral security and integrity. Where voting takes place in multiple locations across the world, maintaining the security and integrity of the voting process presents increased security difficulties and risks to the integrity of the various voter registration, polling and counting phases of an election.

- Financial barriers. In its 2019 OCV technical report, the ECN assessed the high overall cost of such a major operation. The report highlighted that establishing OCV would entail substantial costs, including setting up voting facilities at diplomatic missions, ensuring secure and efficient vote transmission, and managing logistical challenges across various countries. These financial considerations were identified as significant obstacles to the immediate implementation of OCV for Nepali expatriates. Economic considerations would therefore be likely to guide the choice of a future OCV system in Nepal. Financial limitations could also restrict the level of voter information outreach in the host countries where migrants are present in large numbers but also geographically dispersed—for example, in India or in the GCC countries. Financial considerations must also take into account voter turnout, as it may be difficult to justify the major costs of such a complex operation if only a few voters are willing or able to participate.

4. Prospects for enfranchising Nepal’s absent voters

Delivering an election is a high-cost endeavour requiring large-scale planning, meticulous organization and significant operational efforts. The introduction of a viable absentee voting system to enfranchise Nepal’s internal and international absent voters would add to the ordinary management of elections significant levels of legal, procedural, administrative, operational and financial complexity.

In the current context, the prospects for the electoral enfranchisement of Nepal’s absent voters rely heavily on various preconditions, as follows:

- At the political level. Broad consultations would need to take place between key electoral stakeholders, including the Government of Nepal, political parties, the ECN, select ministries and governmental agencies, and civil society organizations, among others, to draw up an ambitious—but realistic—electoral reform roadmap broadly delineating what needs to happen to enfranchise Nepal’s absent voters.

- At the legal/regulatory level. Once political consensus and an agreement are reached on how to proceed with the requisite legal reform, it would be necessary for Nepal’s legislative bodies to amend the electoral legal framework to accommodate the introduction of the designated OCV and inter-/intra-constituency voting methods. Such reform would also need to provide the ECN with the required mandate to introduce and manage absentee voting—and sustain it in the long term. Furthermore, the legal, procedural and operational deadlines for key phases of the electoral process would need to be amended to provide for an early absentee voting period and to bring forward the candidate nomination period to allow for the earlier printing of ballot papers, hence providing sufficient time for their timely delivery to migrants’ host countries and for the ECN to conduct comprehensive voter awareness and education campaigns across the world.

- At the financial level. Introducing absentee voting from the ground up is a significant task entailing extremely high costs. This would entail increasing the budget for Nepal’s elections, possibly by allocating some of the existing foreign affairs’ budget to fund this initiative. A small percentage of the state income generated by migrant remittances and the foreign employment welfare fund could also be devoted to meeting contingencies. In addition, financial assistance could be sought from international donors and organizations interested in supporting inclusive and participatory democracy and upholding migrants’ political rights in Nepal.

- At the voting system’s design and adoption level. The ECN, as the body legally mandated to implement absentee voting, should lead the design of a suitable, cost-effective, sustainable and efficient system to enfranchise Nepal’s absent voters. The process to design and approve a new absentee voting system would require active communication by the ECN with key electoral stakeholders, engaging them and providing information on any decisions made and the rationale for such decisions, addressing any concerns that might arise and allowing their meaningful input in the process. As the ECN has already conducted protracted comparative research on existing absentee voting policies, processes and practices, and assessed some of the most viable options for Nepal, this work provides a basis to begin discussions for the design of an absentee voting system. The ECN could explore the viability of the best system for enfranchising Nepal’s absent voters among the already shortlisted voting methods through polling facilities established at diplomatic missions across the world or by adopting appropriate, transparent, secure—and, thus, trusted—information technology solutions to allow votes to be cast remotely.

- At the planning and operational level. Supporting and sustaining an absentee voting system over multiple electoral cycles is a task that would require considerable planning and complex operational decision-making functions. Such functions could be assigned to a dedicated unit established within the ECN that could be specifically charged with implementing such a complex and important task. This unit would be responsible for planning, budgeting and implementing all processes and operations required for the establishment of an absentee voting system to enfranchise Nepal’s voters on the move, whether they are inside or outside the country. The new unit would have to perform multiple tasks, spanning from recruiting and training its staff, to conducting data collection to capture accurate information on the number and location of internal and international migrants, compiling a register of Nepal’s absent voters, establishing diplomatic contacts with all the host countries concerned, concluding host-country agreements with their governments to allow international migrants in those countries to vote and implementing any technological solutions necessary to facilitate absentee voting.

- At the communication and public outreach level. Introducing an absentee voting system from scratch would require that the ECN engage with key electoral stakeholders and keep them consistently informed of any decisions made and all operations carried out. Accordingly, the ECN could engage reputable mainstream media agencies and civil society organizations to provide regular updates on absentee voting as part of its public outreach and voter information campaigns. Various traditional and digital media tools and platforms could be used for such campaigns, targeting absent voters both in Nepal and in their host countries, to increase their awareness of the system and provide detailed information on how it will work and what will be required from them to register and to vote, also stressing why their vote matters.

As the introduction and first-time implementation of absentee voting could pose numerous risks to the integrity, transparency and security of elections, it would be crucial for it to be introduced incrementally. It would therefore be advisable to consider its progressive implementation, preferably through a pilot project to assess how the new absentee voting system works, where it can be improved and how it could best be expanded, bearing in mind the various financial, management and operational implications.

Abbreviations

ECN Election Commission of Nepal

GCC Gulf Cooperation Council

NRN Non-resident Nepali

OCV Out-of-country voting

UAE United Arab Emirates

References

Adhikari, J., Rai, M. K., Baral, C. and Subedi, M., ‘Labour migration from Nepal: Trends and explanations’, in S. I. Rajan (ed.), Migration in South Asia, IMISCOE Research Series (Cham, Switzerland: Springer, 2023), <https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-34194-6_5>

Ahmad, T., ‘Nepal: President authenticates new amendment to Citizenship Act’, Library of US Congress, 27 June 2023, <https://www.loc.gov/item/global-legal-monitor/2023-06-26/nepal-president-authenticates-new-amendment-to-citizenship-act/?loclr=ealln>, accessed 13 November 2024

Central Bureau of Statistics (CBS), ‘Population Monograph of Nepal’, National Planning Commission Secretariat, Volume II, Social Demography, 2014, <https://nepal.unfpa.org/sites/default/files/pub-pdf/Population%20Monograph%20V02.pdf>, accessed 10 November 2024

Clewett, P., ‘Redefining Nepal: Internal migration in a post-conflict, post-disaster society’, Migration Policy Institute, 18 June 2015, <https://www.migrationpolicy.org/article/redefining-nepal-internal-migration-post-conflict-post-disaster-society>, accessed 5 November 2024

Government of India, ‘Treaty of Peace and Friendship between the Government of India and the Government of Nepal’, Ministry of External Affairs’, 31 July 1950, <https://www.mea.gov.in/bilateral-documents.htm?dtl%2F6295%2FTreaty+of+Peace+and+Friendship=>, accessed 13 November 2024

Gurung, Y. B., ‘Migration from rural Nepal: A social exclusion framework’, HIMALAYA 31/1 (2012), pp. 37–51, Tribhuvan University (2012), <https://www.researchgate.net/publication/256068787_Migration_from_Rural_Nepal_A_Social_Exclusion_Framework>, accessed 2 November 2024

Himalayan Times, The, ‘SC issues directive order to ensure voting rights of Nepali migrant workers’, 22 March 2018, <https://thehimalayantimes.com/kathmandu/supreme-court-issues-directive-order-to-ensure-voting-rights-of-nepali-migrant-workers>, accessed 5 November 2024

International Organization for Migration (IOM), ‘Promoting Strategic and Evidence Based Policy Making’, Nepal Migration Profile, 2018, <https://www.iom.int/project/nepal-migration-profile-promoting-strategic-and-evidence-based-policy-making>, accessed 14 November 2024

—, ‘Migration and Skills Development’, Policy Brief, 2023, <https://nepal.iom.int/sites/g/files/tmzbdl1116/files/documents/National%20Level%20POLICY%20BRIEF%20-%20Jan23.pdf>, accessed 18 November 2024

Kamat, R. K., ‘Call for bill on out-of-country voting’, The Himalayan Times, 10 June 2022, <https://www.thehimalayantimes.com/nepal/call-for-bill-on-out-of-country-voting>, accessed on 18 November 2024

KC, S., ‘Internal migration in Nepal’, in M. Bell, A. Bernard, E. Charles-Edwards and Y. Zhu (eds), Internal Migration in the Countries of Asia (Cham, Switzerland: Springer, 2020), <https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-44010-7_13>, accessed 18 November 2024

Kumar, J., ‘Gorkha Dimension in India-Nepal Relations’, VIF Brief, Vivekananda International Foundation, December 2022, <https://www.vifindia.org/sites/default/files/Gorkha-Dimension-in-India-Nepal-Relations.pdf>, accessed 16 November 2024

National Planning Commission, ‘National Population and Housing Census 2011’, National Report, Volume 01, Government of Nepal, November 2012, <https://unstats.un.org/unsd/demographic-social/census/documents/Nepal/Nepal-Census-2011-Vol1.pdf>, accessed 17 November 2024

Nepali Sansar, ‘Nepal Foreign Education Department: As many as 323,972 students studying abroad’, 24 August 2019, <https://www.nepalisansar.com/education/nepal-foreign-education-department-as-many-as-323972-students-studying-abroad/>, accessed 5 November 2022

NGLearn, ‘Increasing individualism in modern Nepali society (class-12)’, 15 September 2023, <https://krishna000.com.np/increasing-individualism-in-modern-nepali-society/>, accessed 9 November 2024

Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights (OHCHR), ‘The Nepal Conflict Report, Country Report’, 1 October 2012, <https://www.ohchr.org/en/documents/country-reports/nepal-conflict-report>, accessed on 18 November 2024

OnlineKhabar, ‘Election Commission: Studying how Nepalis living abroad can cast votes’, 19 September 2019, <https://english.onlinekhabar.com/election-commission-studying-how-nepalis-living-abroad-can-cast-votes.html>, accessed 5 November 2022

Out of Country Voting Working Group, ‘A Study of the Options and Challenges for Out-of-Country Voting in Nepal’, May 2019, <https://nepalpolicyinstitute.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/02/PB3.pdf>, accessed 14 November 2024

Pokharel, R. R., ‘Behavioral change and family disruption among labor migrants in Nepal’, Management Dynamics, 23/2 (2020), pp. 197–206, <https://doi.org/10.3126/md.v23i2.35822>

Pradhan, T. R., ‘Nepalis abroad set to exercise voting right’, The Kathmandu Post, 3 September 2018, <https://kathmandupost.com/national/2018/09/03/nepalis-abroad-set-to-exercise-voting-right>, accessed 12 November 2024

Sherpa, D., ‘Labour Migration and Remittances in Nepal’, Case Study Report, International Centre for Integrated Mountain Development, 2010, <https://doi.org/10.53055/ICIMOD.530>

Shukla, D., ‘India-Nepal relations: Problems and prospects’, The Indian Journal of Political Science, 67/2 (April–June 2006), pp. 355–74, <https://www.jstor.org/stable/pdf/41856222.pdf>, accessed 16 November 2024

South Asia Time, ‘Nepal breaks new ground: Dual citizenship granted to overseas citizens’, 31 May 2023, <https://www.southasiatime.com/2023/05/31/nepal-breaks-new-ground-dual-citizenship-granted-to-overseas-citizens/>, accessed 14 November 2024

Taylor, M., ‘Disenfranchised – millions of Nepalis have no voting rights’, The Record, 21 March 2022, <https://www.recordnepal.com/disenfranchised-%E2%80%93-millions-of-nepalis-have-no-voting-rights>, accessed 18 November 2024

United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR), ‘2016 Global Report on Internal Displacement - Nepal: Obstacles to Protection and Recovery’, 1 May 2016, <https://refworld.org/reference/annualreport/idmc/2016/en/111497>, accessed 18 November 2024

About the author

Gopal Krishna Siwakoti, PhD, is the President of the international Institute for Human Rights, Environment and Development (INHURED International) and has special consultative status with the UN Economic and Social Council (ECOSOC). With nearly 40 years of experience in the field of human rights protection and promotion, he has authored, edited and produced several books, research reports, journals, films and documentaries on electoral freedom, migration, refugees, disaster displacement, transitional justice, human rights and peace.

About this series

This case study is part of the ‘Absent Voters of South Asia’ project, which falls under the project of ‘Migrations and Elections’ that covers member states of the South Asian Council for Regional Cooperation (SAARC), such as Afghanistan, Bangladesh, Bhutan, India, the Maldives, Nepal, Pakistan and Sri Lanka.

- Gurkhas are soldiers from Nepal recruited into the British Army.

- The Treaty granted to the nationals of one country in the territories of the other the same privileges in the matter of residence, ownership of property, participation in trade and commerce, and movement.

- Nepali migrants who acquire citizenship in another country must relinquish their citizenship of Nepal.

© 2024 International Institute for Democracy and Electoral Assistance

International IDEA publications are independent of specific national or political interests. Views expressed in this publication do not necessarily represent the views of International IDEA, its Board or its Council members.

With the exception of any third-party images and photos, the electronic version of this publication is available under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 (CC BY-NC-SA 4.0) licence. You are free to copy, distribute and transmit the publication as well as to remix and adapt it, provided it is only for non-commercial purposes, that you appropriately attribute the publication, and that you distribute it under an identical licence. For more information visit the Creative Commons website: <http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/4.0>.

Design and layout: International IDEA

DOI: <https://doi.org/10.31752/idea.2024.103>

ISBN: 978-91-7671-856-8 (PDF)

ISBN: 978-91-7671-923-7 (HTML)