The Absent Voters of India

Challenges and Prospects for the Enfranchisement of Migrants

Introduction

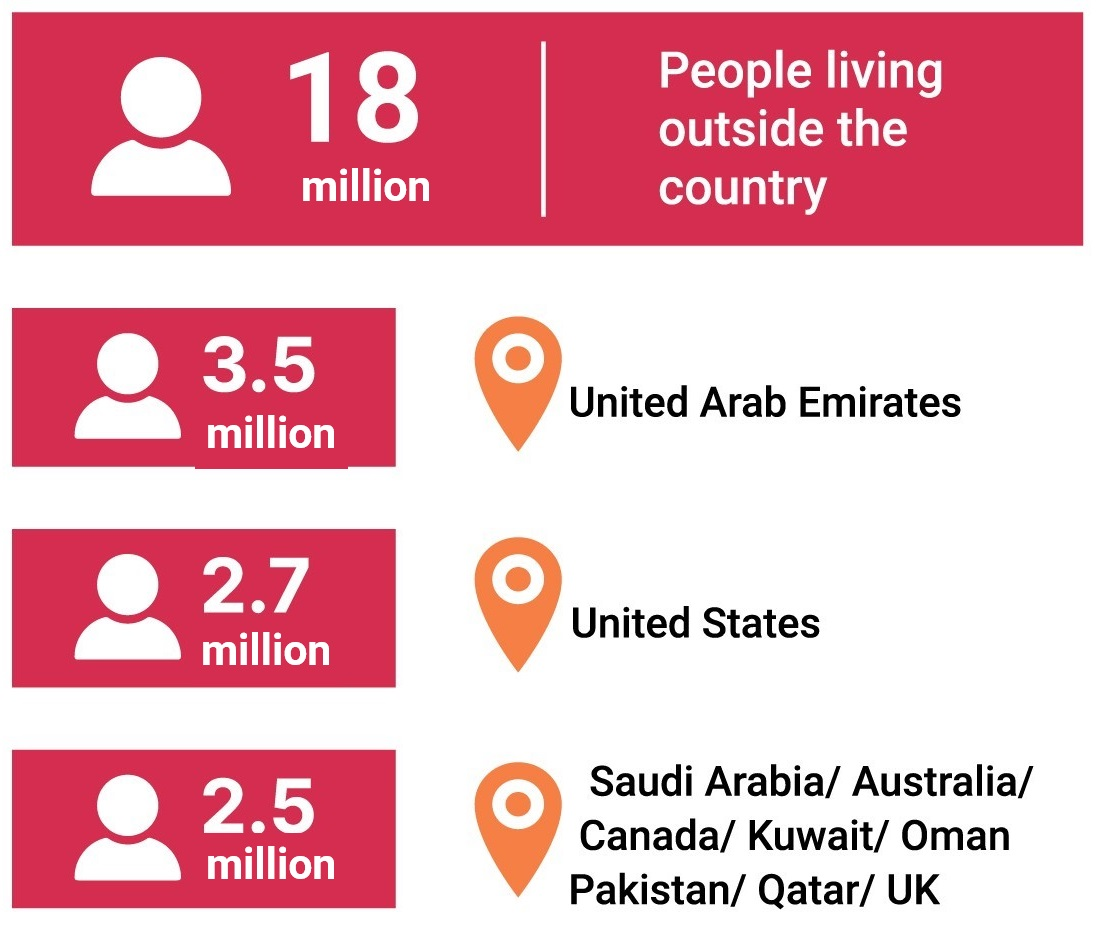

This case study explores the complex landscape of India’s internal and international migration and its profound impact on the nation’s political formation. The electoral process, primarily designed around stable voter residency, limits the participation of a constantly mobile population both within and outside the country. In fact, with an estimated 18 million citizens living abroad and 37 per cent of India’s population having migrated internally, the absence of a viable voting system to enfranchise tens of millions of these absent voters stands in the way of truly inclusive and participatory electoral processes in the world’s largest democracy.

This study highlights the need for proactive, viable and trusted enfranchisement solutions; targeted information campaigns; and enhanced voter education efforts to effectively ensure that, in India’s elections, no voter is left behind.

1. India’s migration: Background and characteristics

The very essence of India is its history of various waves of migration, settling one after the other in different parts of the country, as expressed in the words of the renowned poet Firaq Gorakhpuri: ‘the caravans of people from all parts of the world kept on coming and settling … and led to the formation of India’ (Philoid 2023).

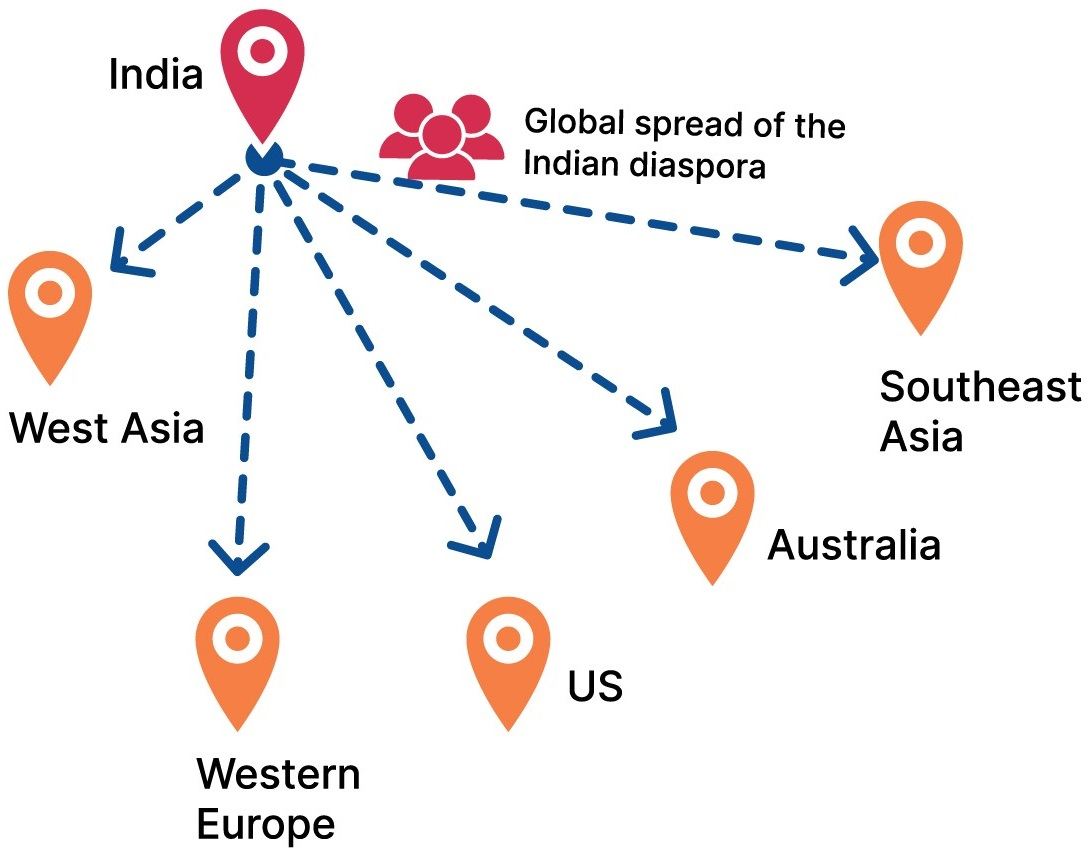

Similarly, large numbers of people from India have also migrated to other countries and regions in search of better opportunities, primarily to Australia, East and South East Asia, West Asia, Western Europe and the United States. In terms of the global spread of the Indian diaspora, international migration in modern times can be broadly classified into two main periods—colonial and post-independence.

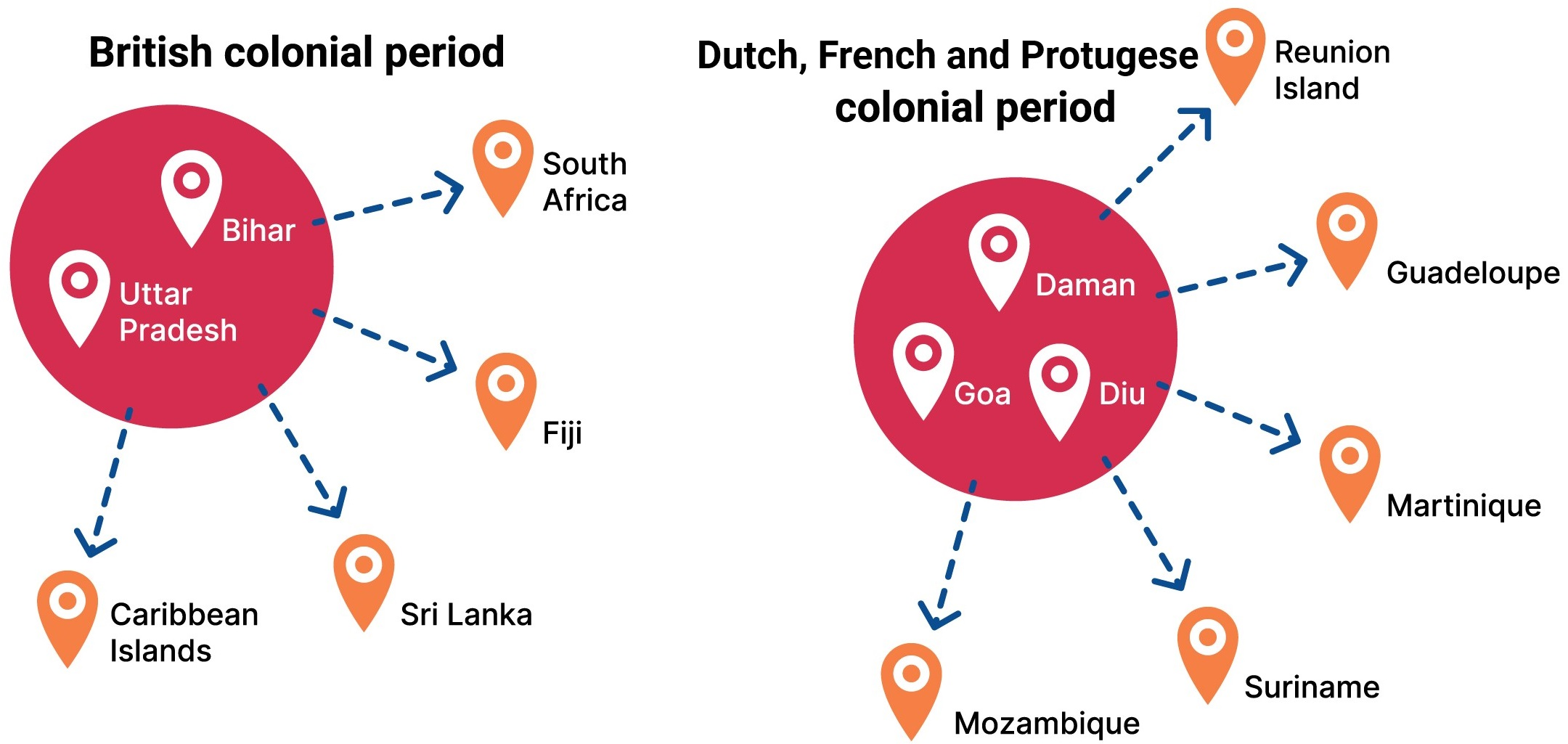

In the 19th century, in the British colonial period, millions of indentured labourers—mostly from villages in Bihar and Uttar Pradesh—were sent to British colonies such as the Caribbean islands, Fiji, Mauritius, South Africa and Sri Lanka, to work as plantation workers or in construction and rail projects. Indian citizens also migrated from the Dutch, French and Portuguese colonies in India, such as Daman, Diu and Goa, to Guadeloupe, Martinique, Mozambique, Réunion Island and Suriname. These migratory flows occurred under the time-bound contract known as the Girmit Act (the 1871 Indian Emigration Act).

In the post-independence period after 1947, major cross-border migration occurred at the time of the partition of India and again during the subsequent partition of Pakistan in 1971–1972. There were also significant movements of Indian migrants to nearby countries—such as Brunei, Indonesia, Malaysia, Singapore and Thailand, as well as to African states—as professionals, artisans, traders and factory workers migrating in search of better economic opportunities. This migratory trend continues today (Kumar 2022).

In the wake of the Gulf oil boom of the 1970s, India saw a steady outflow of semi-skilled and skilled labour. This time was also characterized by a significant outflow of entrepreneurs, store owners, professionals and business owners to Western countries (Philoid 2023).

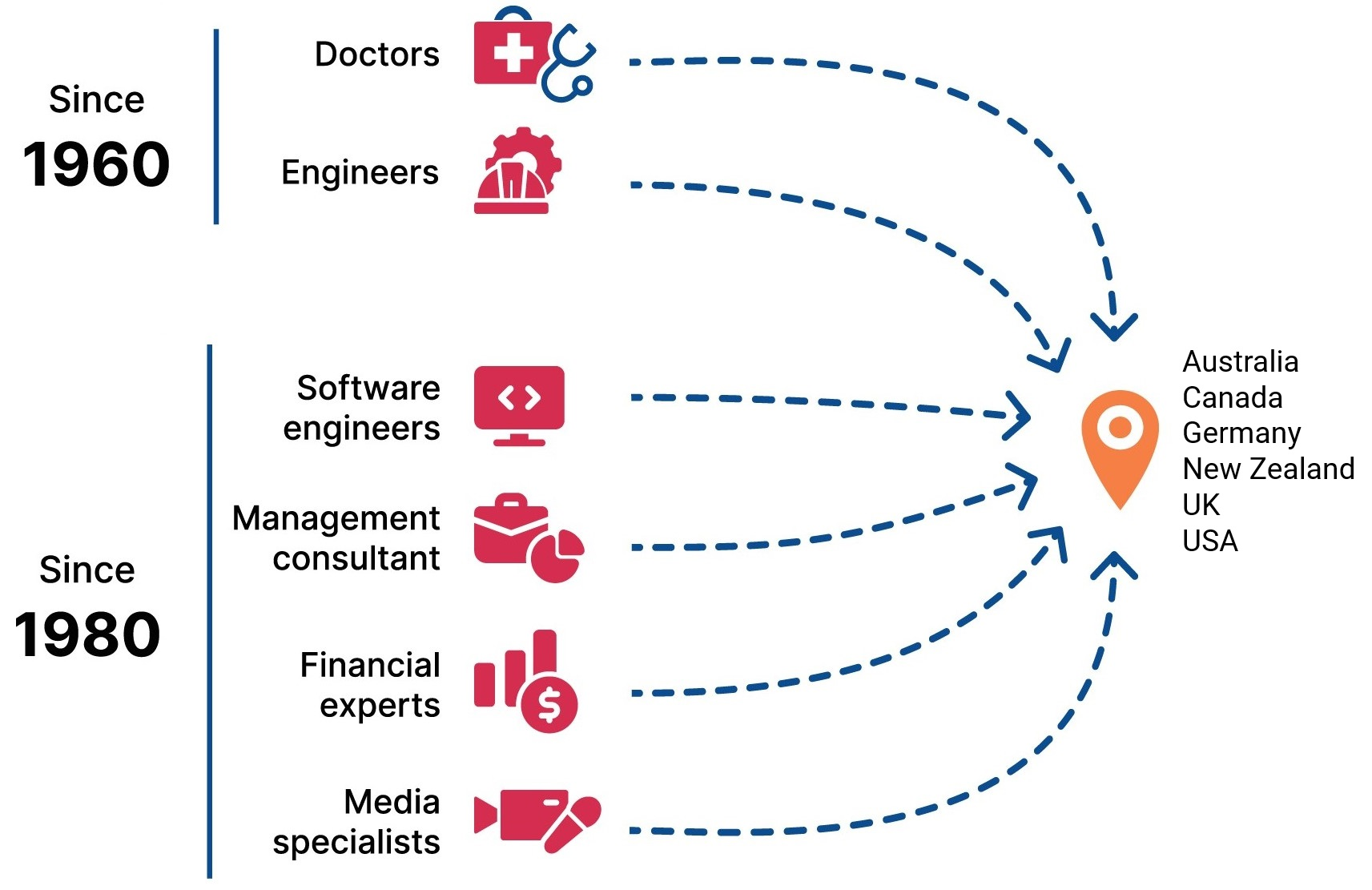

In more recent times, flows of international migrants have consisted of mostly professionals, such as engineers and doctors (since the 1960s) or software engineers, management consultants, financial experts and media specialists (since the 1980s), who have migrated to Australia, Canada, Germany, New Zealand, the United Kingdom and the USA, as well as other European countries. These professionals are among the most highly educated, highest-earning and most prosperous segments of India’s society. Since the liberalization of India’s economy in the 1990s, education-related and knowledge-based Indian professionals have dominated the Indian diaspora (Baghat et al. 2015).

According to a report published in 2020 by the United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs (UN DESA), 18 million Indians were living outside their country of birth in 2020, making it the largest transnational community in the world. The report shows that India’s diaspora is distributed across the United Arab Emirates (3.5 million migrants), the USA (2.7 million) and Saudi Arabia (2.5 million), as well as Australia, Canada, Kuwait, Oman, Pakistan, Qatar and the United Kingdom.

India’s internal migratory movements are even larger. According to the 2011 Census,1 455.8 million (about 37 per cent) of its 1.21 billion population are internal migrants, or citizens who are now settled in a place different from that of their previous residence or place of birth (Mistri 2022).

Two typologies of migratory flows are common in India:

- long-term migration, or the resettlement of an individual or household; and

- short-term, temporary or seasonal/circular migration, through which migrants remain closely connected to their places of origin through regular movement between the source and destination (UNESCO 2012).

India’s migration may be further classified as over a short or a long distance, short term or permanent and voluntary or forced (De 2019). The last Census has also shown an increase in both urban migration and interstate migration.

According to the Economic Survey2 of 2018–2019, India’s informal economy is made up of workers in the unorganized sector, who constitute about 93 per cent of the country’s total workforce. Approximately 175 million migrants in India move internally to work in the informal sector.

Data from the 2011 Census shows that most Indians migrate within the same district or between districts in the same state. Just 12 per cent of those registered as ‘migrants’ in the 2011 Census (around 54 million people) had moved from one state to another, while nearly 396 million had moved within their home state. There are several conspicuous migratory corridors for interstate migration within the country—from Bihar to Delhi and Maharashtra, from Bihar to Assam and West Bengal, from Bihar to Haryana and Punjab, from Uttar Pradesh to Maharashtra, from Odisha to Gujarat, from Odisha to Andhra Pradesh and from Rajasthan to Gujarat.

Internal migration rates are recorded as higher in high-income states, such as Gujarat, Haryana, Karnataka, Maharashtra, Punjab and West Bengal. Low-income states, such as Bihar, Chhattisgarh, Jharkhand, Orissa, Rajasthan and Uttar Pradesh, report relatively higher rates of migration out of state. According to the 2011 Census, migrants from other states constitute almost one-third of the combined population of Delhi and Mumbai (around 9.9 million of 29.2 million), while the number of interstate migrants from Bihar and Uttar Pradesh is disproportionately high, as 20.9 million people migrated from these two states alone. The Hindi belt appears to be the main place of origin for interstate migrants, as four states—Bihar, Madhya Pradesh, Rajasthan and Uttar Pradesh—account for 50 per cent of India’s total interstate migrants.

2. Drivers of migration within and outside India

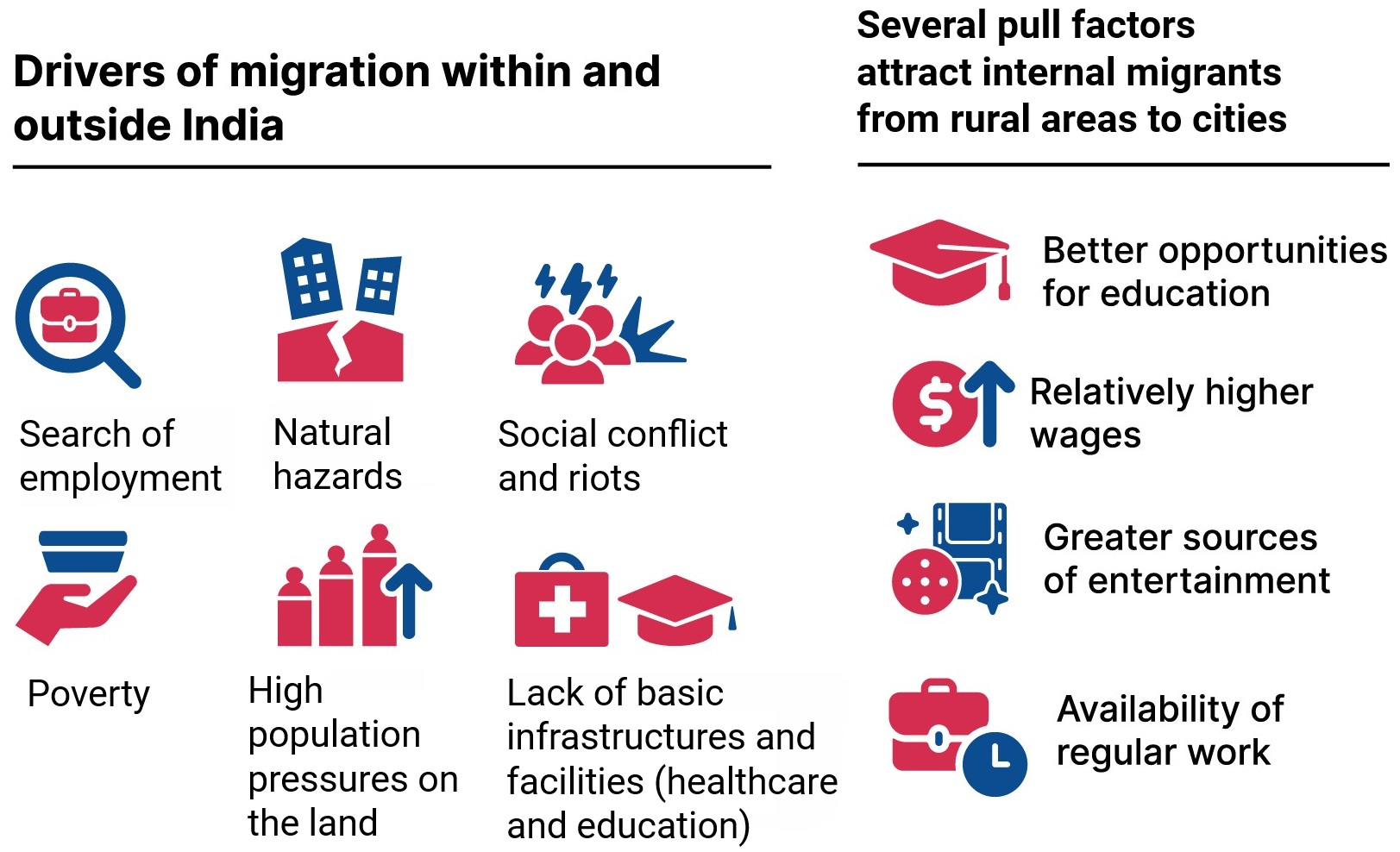

India’s internal and international migratory movements are driven by different push and pull factors. People migrate internally, from rural to urban areas, pulled from one side by the prospect of better employment opportunities, and pushed from the other by poverty and high population pressures on the land, as well as the lack of basic infrastructure and facilities, such as healthcare and education (Raj, Kumari and Prasad 2024).

In addition, natural disasters such as floods, droughts, storms, earthquakes and tsunamis as well as social or ethnic conflict and riots have also pushed internal migration. Several pull factors attract internal migrants from rural areas to cities, notably the prospect of better education opportunities, the availability of regular work, relatively higher wages and greater sources of entertainment (Irudaya Rajan and Rajagopalan 2023).

Push and pull patterns of migration work on two separate social groups of international and internal migrants in India. One group comprises members of the privileged social class from the higher castes who generally migrate to earn higher incomes or pursue educational opportunities and a better standard of living—the ‘aspirants’. A second group is dominated by the socio-economically deprived, with a meagre asset base and few educational attainments (Debnath and Nayak 2021). This distressed group is largely from members of the Scheduled Castes, Scheduled Tribes and ‘Other Backward Castes’,3 whose migration is often linked to a struggle for basic survival. Distressed migration is primarily temporary and seasonal in character and distinguished from permanent or long-term migration where migrants are generally employed in regular jobs. Distressed migration has increased remarkably in India since the 1990s with the collapse of rural employment (Alam 2021).

The drivers of migration are different for women and men in India. Work or employment is the main cause of migration on the part of men, whereas women’s migration is mostly obligatory, linked to marriage or the movement of parents or earning family members. Only a small proportion of women migrate primarily for work-related reasons (Francis and Dubey 2019).

Typically, Indians migrate from a place of low opportunity and low safety to a place of greater opportunity and greater safety. This, in turn, creates both benefits and problems for the areas people migrate from and to.

3. Status of the electoral enfranchisement of India’s absent voters

Thus far, India’s electoral journey has been remarkable in terms of the enfranchisement of the electorate in what is often called the largest democracy in the world. The Constitution of India confers the right to register as voters on all citizens who have attained the qualifying age, subject to any disqualification on account of a conviction as specified under the law. Section 20 of the Representation of the People Act establishes that a citizen can be registered as a voter in any constituency of ‘ordinary residence’. However, enrolment to vote is allowed only at one place of residence. Where a citizen migrates to another constituency, he or she must register to vote at the new place of residence while also requesting that his or her name be deleted from the voters’ list in the constituency of previous residence.

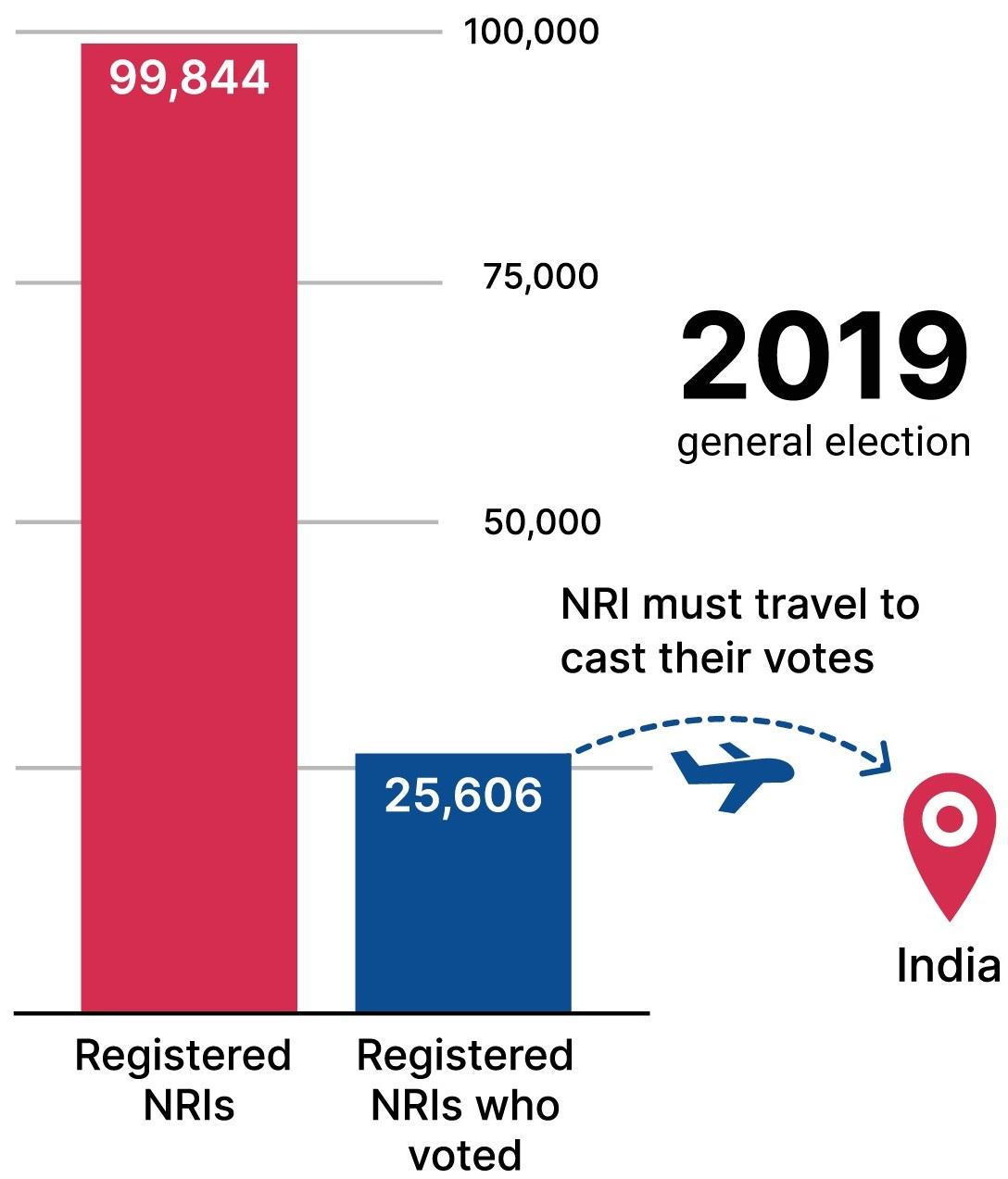

Overseas citizens—or non-resident Indians (NRIs)—deemed to be ordinarily resident at the in-country address shown in their passport gained the right to vote in 2011. The government issued a notification permitting them to apply while overseas to register to vote at their constituency of ordinary residence in India. Because NRIs still must travel to India to cast their votes, however, this measure has had only a limited effect on enfranchisement. Only 25,606 of the around 99,844 registered NRIs voted in the 2019 general election (Balan 2024). While, at the time of this writing, the Election Commission of India (ECI) had not yet released official statistics on voter turnout in respect of NRIs for the 2024 elections to the Lok Sabha (the lower house of India’s bicameral national parliament), more than 118,000 overseas Indians registered to vote, the highest number being from the state of Kerala.

Since 1961 the ECI has administered a limited system of absentee voting in the form of postal voting extended to ‘service voters’,4 citizens under preventive detention5 and staff on election duty outside their place of registration. Instead of a postal vote, service voters may opt to vote by proxy or through an electronically transmitted postal ballot system (The Hindu 2022).

In pursuance of the 2019 Conduct of Elections (Amendment) Rules and the 2020 Conduct of Elections (Amendment) Rules, the use of postal ballots has been gradually extended in recent years, especially in the light of the Covid-19 pandemic, to additional categories of absent voters, such as (a) voters over the age of 80; (b) people with disabilities flagged on the electoral roll; and (c) people who tested positive for Covid-19 and their contacts.

Another form of absentee voting is the special voting facilities provided at transitory camps. In the late 1980s and early 1990s, following an armed rebellion and ensuing violence, large numbers of voters registered in different parts of what was then the state of Jammu and Kashmir,6 particularly in the Kashmir region, were forced to leave their native places of residence (Bose and Jalal 2021). These displaced populations still reside in transitory camps in Jammu and Delhi or in other parts of the region. Many have been awaiting the opportunity to return to their homes. Because of their ethnic, cultural and emotional ties with their ancestral land, and to retain permanent resident status in their ‘native state’, even if displaced, they have been unwilling to register to vote in the constituencies to which they have migrated (Singh 2021).

To fulfil a pledge to keep their names on the voter rolls of their place of origin, those internally displaced voters who left the Kashmir Valley after 1 April 1989 are recognized as ordinarily resident and therefore eligible to vote in their constituencies of origin. Their offspring, who have now attained voting age, have also been registered on those voting rolls based on their application. At the time of the election to the state legislative assembly in 1996, a special scheme was devised for these internally displaced voters, referred to as ‘notified voters’, to enable them to vote by postal ballot for candidates in their places of origin (Bisht 2024).

Having appraised this absentee voting scheme, the ECI took steps in the following general elections, including the 2024 general election (Economic Times 2024), to allow Kashmir’s displaced population to be enfranchised either through postal voting or in person in special polling stations established in the transitory camps.

Despite the extraordinary numbers of India’s internal and international migrants, an inclusive, viable and sustainable absentee voting system has not yet been developed and put into use. Most of these absent voters, while nominally eligible to vote, currently remain unable to participate in national elections in practice unless they return, whether from abroad or elsewhere within the country, to their constituencies of registration to vote.

In 2015 the ECI commissioned the Tata Institute of Social Sciences (TISS) to produce a study titled ‘Inclusive Elections in India: A Study on Domestic Migration and Issues in Electoral Participation’. The TISS study found that states with higher rates of internal migration were directly associated with lower voter turnout (Jain 2023).

According to the ECI, for India’s 2024 general election, over 968 million people were registered to vote, making it the largest electorate in the world and showing an increase from the 2019 elections (PIB Delhi 2024). The size of the electorate for the 2019 general election was 910.1 million voters, an increase of 71 million (8.51 per cent) from the 2014 general election (PIB Delhi 2021). The voter turnout for India’s 2024 general election was reported at 65.79 per cent, while in 2019 it was 67.47 per cent. This information is corroborated by the ECI’s official results, which indicate that 642 million7 out of 968 million registered voters participated in the 2024 elections (Kumar and Singh 2024). There is no data on the number of disenfranchised internal or international migrants, but the absence of provisions for inter-/intra-state or inter-/intra-constituency absentee voting is thought to disenfranchise a very large proportion of the electorate across India every year (Philip 2024).

4. Challenges for the electoral enfranchisement of India’s absent voters

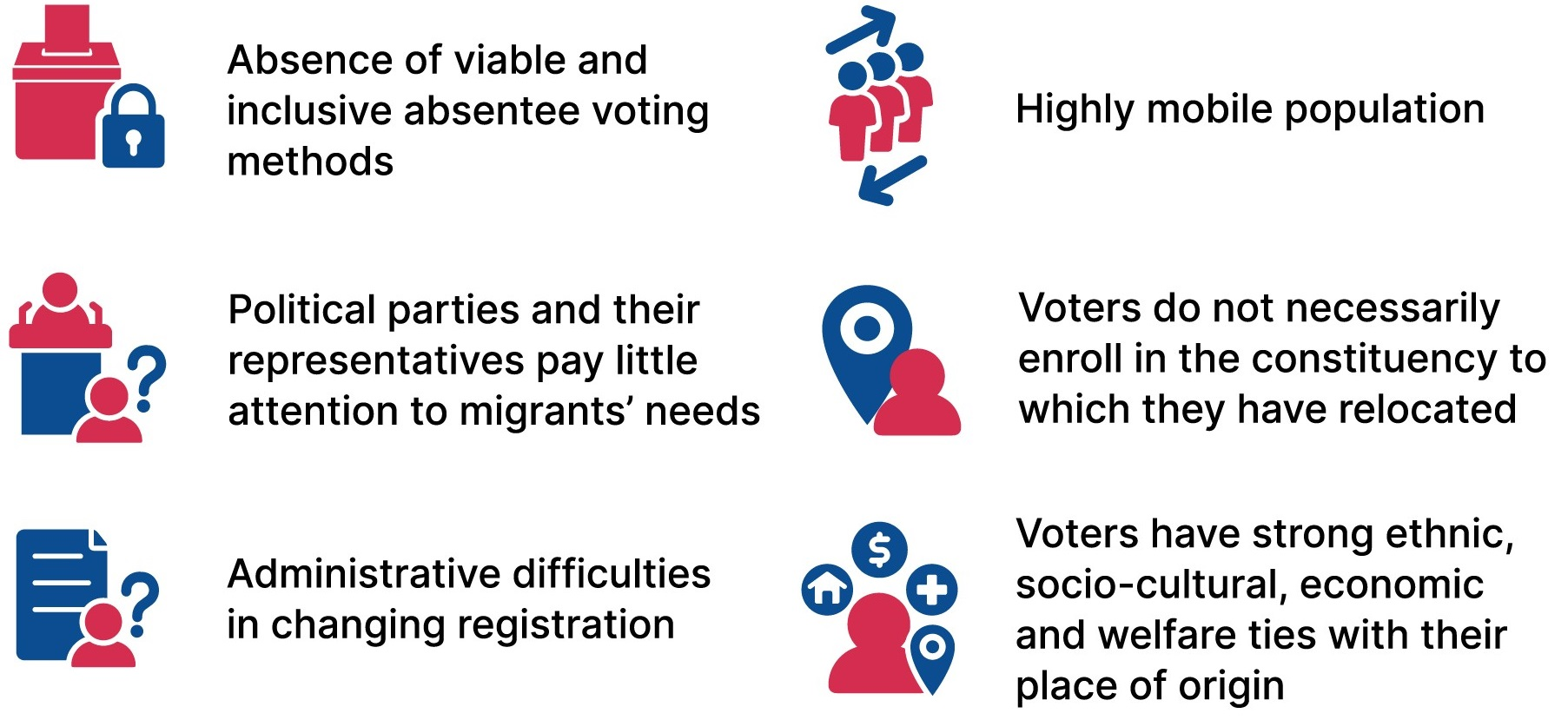

The predominant pattern of migration in India is one of constant mobility, and a main factor leading to the disenfranchisement of migrants is that voting rights assume a voter’s stable residence. As voters are entitled to vote only at their assigned polling station in their constituency of registration, migrants are forced to choose between working and voting. As a result, large numbers of international and internal migrants have been consistently unable to exercise their voting rights in elections at the various levels—for the Lok Sabha, the state assemblies or local village councils (panchayats) (Philip 2024).

Additionally, as neither voting nor registering to vote is compulsory in India, migrant populations do not necessarily enrol as voters in the constituency to which they have relocated. There are various reasons for this, from administrative difficulties with changing their constituency of registration to uncertainties over the stability and duration of their employment or the existence of strong ethnic, socio-cultural, economic and welfare ties with their place of origin, or more simply a lack of information or a failure to meet documentation requirements (Gaikwad and Nellis 2021). As most of the government’s expanded social security programmes related to food, education, health and housing entitlement are available to beneficiaries only at their place of origin, most migrants remain closely connected with the villages where their family and friends live (Gaikwad and Nellis 2021).

However, the failure to change their registration to vote in their constituency of ordinary residence continues to represent one of the most serious barriers to the enfranchisement of India’s internal migrants. As non-registered residents, they are not eligible to vote in their new constituency, and most cannot afford to return to vote in their constituency of origin, where they are non-resident registered voters. The problem is intense for the segment of floating seasonal or temporary migrants who continue to move back and forth between both places. Many are unable to produce proof of identity or residence in their place of work, and so become socially, politically and electorally invisible (Aggarwal 2019).

A large proportion of India’s international migrants, 70 per cent of whom are unskilled or semi-skilled labourers, have moved to one of the states of the Gulf Cooperation Council (Wadhawan 2018). Denied their right to vote, they are the most voiceless in India. The ability to vote could empower them at work.

Most internal migrants are unable to vote in national elections because they are invariably scheduled in the months of April and May. This period coincides with the time in which many distressed regions see their largest annual exodus as migrant labourers seek work to survive. Many are footloose migrants who move from place to place and cannot afford to return to their places of origin to register to vote or to vote. The media often reports on the hundreds of thousands of agricultural labourers who migrate within South India or outside their state, or from the tribal belts, at this time of year and are thus unable to vote (Dasgupta 2023).

Certain segments of the population—such as women, rural residents, people with low levels of or no literacy, ethnic minorities, youth and people with disabilities—tend to be more vulnerable to electoral disenfranchisement. Most migrants move within or leave India on a seasonal or temporary basis. They belong to the poor, illiterate or less educated social classes for which changing their registration every time they move is neither an attractive nor a practical option. Moreover, the costs of travelling back to their constituencies of registration are even more unaffordable, resulting in their inability to participate in elections in their home constituencies (Keshri and Bhagat 2010).

The voter enrolment process in a new constituency requires the provision of adequate proof of residence.8 In most migrants’ precarious circumstances this requirement can be very difficult or impossible to comply with given the temporary and often quite informal nature of migrant housing. This barrier to registration (and hence to voting) is well documented and was noted by a former chief election commissioner: ‘The process of enrolling takes time. It requires the migrant worker to submit proof of the new residence, which is not always available. On election day, not many migrant workers can return to their native place to vote, as their employers may not give them time to leave, or they may not be able to afford the journey. So, they end up not voting’ (Jain 2019).

Furthermore, the dearth of any reliable official data on migration within and outside India is a glaring omission, as was highlighted at the height of the Covid-19 pandemic and related lockdowns, when the minister of state for labour and employment stated that no data was available on migrants or on the help granted by the government to distressed migrants who walked, often very long distances, back to their places of birth during the national lockdown (Nath 2020). These circumstances brought renewed attention to the fact that most internal migrants are denied even basic civil and political rights because internal migration is not a priority for government policy or practice.

Finally, political parties and their representatives pay little attention to migrants’ needs, as the latter do not usually return to vote. Political parties and their representatives in the migrants’ work location in the country or abroad are similarly deaf to migrants’ concerns, as most migrants cannot exercise their voting rights. This further strengthens the demand for a policy initiative that can provide access to the electoral franchise for migrants so they can reclaim or assert their political rights alongside their fellow citizens.

5. Prospects for the electoral enfranchisement of India’s absent voters

Aware of the need to include India’s migrants in the electoral process, the ECI has been trialling an absentee voting system that would enable electors to cast their votes digitally from anywhere in the country (The Indian Express 2023). At present, however, it is unclear to which segments of the electorate this voting method might be extended.

In 2020 the ECI submitted a proposal to the Ministry of Law and Justice to extend absentee voting by postal ballot to overseas NRIs (Ramani 2020). This proposal could be approved by an amendment to the 1961 Conduct of Election Rules by both houses of parliament. A similar reform was attempted in 2015 when an expert committee established by the ECI submitted a proposed legal amendment to the Ministry of Law and Justice contemplating changes to the electoral law to enfranchise overseas citizens using proxy voting. In 2018 the government submitted a bill to the Lok Sabha proposing the granting of proxy voting rights to overseas electors through an amendment to the 1951 Representation of the People Act. The bill was passed by the Lok Sabha but was still before the Rajya Sabha (the upper house) when it lapsed following the dissolution of the 16th Lok Sabha in 2019.

Deliberation on the introduction of a viable and accessible absentee voting system for overseas Indians continues. Political parties—among them the Communist Party of India—insist that the government, while moving to extend voting rights to NRIs, must not ignore the voting rights of internal migrants. Civil rights groups have also urged the ECI to facilitate absentee voting through a postal ballot to ensure that every segment of the eligible adult Indian population is enfranchised.

In 2015 the ECI established an expert committee to study the feasibility of enfranchising internal migrants wherever they reside without having to travel to their place of ordinary residence. This initiative was in response to a Supreme Court directive addressing the disenfranchisement of domestic migrants (Chari 2015). The study concluded that, in the absence of a clear legal definition of ‘migrant worker’, and of official, reliable data on the number of such voters, the introduction of absentee voting was, at that time, not feasible (Kumar and Dhar 2021). The Ministry of Law and Justice also expressed concerns about the feasibility of introducing an e-voting system to enfranchise international migrants on the grounds that there would be significant difficulties implementing such a scheme in a country as large as India, in addition to creating major security concerns.

Migration is the route to survival for a significant proportion of the rural population of India. The relentless pace of urbanization in India means that migration is likely to increase. It is important to recognize that, without its internal and international migrants, the Indian economy would come to a standstill (Mishra and Singh 2024).

The management of elections in India is not just about size and the magnitude of the process through which the world’s largest democracy comes together to vote. Election management also requires greater efforts aimed at the inclusion, enfranchisement, political participation and representation of a large segment of the electorate that is unjustly deprived of fundamental voting rights because of its absence, which, in most cases, is hardly ever voluntary. Indian elections have to innovate and transform themselves to respond to the challenges of enfranchising millions of the country’s absent voters through necessary changes to the legal framework leading to a more inclusive national policy and through the adoption of the most suitable and sustainable absentee voting system. One essential task will be to devise a mechanism that maintains an accurate database of India’s internal and international migrants to facilitate their inclusion and thus participation in future electoral processes.

Providing migrants with proof of identity and residence is one of the more serious challenges to electoral inclusion and participation. It would therefore be advisable to aim for a more inclusive voter enrolment system. The ECI could play a more proactive role, enabling it to meet its goal of ‘no voters left behind’.9 Targeted information campaigns and voter education efforts on migrants’ rightful electoral inclusion, participation and political representation could also play a crucial role.

Abbreviations

ECI Election Commission of India

NRI Non-resident Indian

TISS Tata Institute of Social Sciences

References

Aggarwal, V., ‘Missing migrant voters in India and why they matter; states with higher rates of migration known to have lower voter turnouts’, Firstpost, 15 April 2019, <https://www.firstpost.com/india/missing-migrant-voters-in-india-and-why-they-matter-states-with-higher-rates-of-migration-known-to-have-lower-voter-turnouts-6450361.html>, accessed 14 October 2024

Alam, M. A., ‘Reservations in India: Constitutional and historical perspectives, and contemporary concerns’, in G. Sudhir, M. A. Bari, A. U. Khan and A. Shaban (eds) Muslims in Telangana: A Discourse on Equity, Development, and Security. Dynamics of Asian Development (Singapore: Springer, 2021), <https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-33-6530-8_16>

Baghat, R. B, Das, K. C., Prasad, R. and Roy, T. K, ‘International Migration from Gujarat: The Magnitude, Process and Impact’, Research Brief No. 15, International Institute for Population Sciences (IIPS) (2015), <https://www.researchgate.net/publication/280113374_International_Migration_from_Gujarat_The_Magnitude_Process_and_Impact>, accessed 13 November 2024

Balan, D., ‘Rewind: Leaving NRI voters behind’, Telangana Today, 2 May 2024, <https://telanganatoday.com/rewind-leaving-nri-voters-behind>, accessed 12 November 2024

Bisht, S., ‘What does scrapping of ‘‘cumbersome’’ Form M mean for Kashmiri Pandit voters in Jammu, Udhampur?’, News 18, <https://www.news18.com/explainers/what-does-scrapping-of-cumbersome-form-m-mean-for-kashmiri-pandit-voters-in-jammu-udhampur-8852282.html>, accessed 9 November 2024

S. Bose and A. Jalal (eds), Kashmir and the Future of South Asia. Routledge Contemporary South Asia Series (Abingdon and New York: Routledge, 2021), pp. 91–115, <https://www.routledge.com/Kashmir-and-the-Future-of-South-Asia/Bose-Jalal/p/book/9780367634902>, accessed 11 November 2024

Chari, M., ‘Supreme Court gives NRIs the right to vote, but internal migrants are unable to do so’, Scroll.In, 13 January 2015, <https://scroll.in/article/700175/supreme-court-gives-nris-the-right-to-vote-but-internal-migrants-are-unable-to-do-so>, accessed 3 November 2024

Dasgupta, D., ‘India plans remote voting for internal migrants’, The Straits Times, 9 January 2023, <https://www.straitstimes.com/asia/south-asia/india-plans-remote-voting-for-internal-migrants>, accessed 21 October 2024

De, S., ‘Internal migration in India grows, but inter-state movements remain low’, People Move, World Bank Blogs, 18 December 2019, <https://blogs.worldbank.org/en/peoplemove/internal-migration-india-grows-inter-state-movements-remain-low>, accessed 12 November 2024

Debnath, M. and Nayak, D. K., ‘Determinants of temporary migration of rural small, marginal and landless households in West Bengal, India’, SN Social Sciences, 1/255 (2021),<https://doi.org/10.1007/s43545-021-00262-y>

Economic Times Government, ‘General elections 2024: Kashmiri migrants in Jammu, Udhampur no longer required’, 13 April 2024, <https://government.economictimes.indiatimes.com/news/governance/general-elections-2024-kashmiri-migrants-in-jammu-udhampur-no-longer-required-to-fill-form-m-to-vote/109263694>, accessed 11 November 2024

Francis, A. and Dubey, D., ‘Women, work, and migration’, India Development Review (IDR), 6 March 2019, <https://idronline.org/women-work-and-migration/>, accessed 10 November 2024

Gaikwad, N. and Nellis, G., ‘Overcoming the political exclusion of migrants: Theory and experimental evidence from India’, American Political Science Review, 115/4 (2021), pp. 1129–46, <https://www.cambridge.org/core/journals/american-political-science-review/article/overcoming-the-political-exclusion-of-migrants-theory-and-experimental-evidence-from-india/7EACC7F5656A7981B5D6D39142DE90FA>, accessed 10 October 2024

The Hindu, ‘Remote voting: On postal ballot for NRIs’, Editorial, 5 November 2022, <https://www.thehindu.com/opinion/editorial/remote-voting-the-hindu-editorial-on-postal-ballot-for-nris/article66096200.ece>, accessed 7 November 2024

The Indian Express, ‘Remote voting a work in progress, meeting with parties a success: CEC’, 19 January 2023, <https://indianexpress.com/article/india/remote-voting-progress-meeting-parties-success-cec-8390348/>, accessed 7 November 2024

Irudaya Rajan, S. and Rajagopalan, A., ‘Inter-state migrant workers in India: Policy for a decent world of work’, People Move, World Bank Blogs, 14 July 2023, <https://blogs.worldbank.org/en/peoplemove/inter-state-migrant-workers-india-policy-decent-world-work>, accessed 12 November 2024

Jain, B., ‘Let vote move with voter: Why it’s not a reality yet’, Times of India, 8 January 2019, <https://timesofindia.indiatimes.com/india/let-vote-move-with-voter-why-its-not-a-reality-yet/articleshow/67429573.cms>, accessed 27 October 2024

—, ‘How the EC plans to let migrants vote outside their home state’, Times of India, 10 January 2023, <https://timesofindia.indiatimes.com/india/how-ec-plans-to-let-migrants-vote-outside-their-home-state/articleshow/96869065.cms>, accessed 5 November 2024

Keshri, K. and Bhagat, R. B., ‘Temporary and seasonal migration in India’, Università degli Studi di Roma ‘La Sapienza’, Genus, 66/3 (2010), pp. 25–45, <https://www.jstor.org/stable/pdf/genus.66.3.25.pdf?addFooter=false>, accessed 29 October 2024

Kumar, A. and Dhar, S., ‘Migration and inclusive elections’, in A. Kumar and R. B. Bhagat (eds), Migrants, Mobility and Citizenship in India (London: Routledge, 2021), pp. 51–64, <https://doi.org/10.4324/9780367765477>

Kumar, A. and Singh, N., ‘LS polls: EC reports record 642M voters, vows to combat fake narratives’, Business Standard, 3 June 2024, <https://www.business-standard.com/elections/lok-sabha-election/ls-polls-ec-reports-record-642m-voters-vows-to-combat-fake-narratives-124060300625_1.html>, accessed 12 November 2024

Kumar, P., ‘Exploring the Indian Diaspora’s Role in Southeast Asia’s Development’, Diaspora & Transnational Communities, Sociology Institute, 6 November 2022, <https://sociology.institute/diaspora-transnational-communities/indian-diaspora-role-southeast-asia-development>, accessed 13 November 2024

Mishra, P. S. and Singh, R. ‘Internal migration, remittances, and socioeconomic development in India: Evidence from a national sample survey’, in A. A. Ullah (ed.), Handbook of Migration, International Relations and Security in Asia (Singapore: Springer, 2024), <https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-99-8001-7_40-1>

Mistri, A., ‘Migration from North-East India during 1991–2011: Unemployment and ethnopolitical issues’, Indian Journal of Labour Economics, 65 (2022), pp. 397–423, <https://doi.org/10.1007/s41027-022-00379-5>

Nath, D., ‘Govt. has no data of migrant workers’ death, loss of job’, The Hindu, 14 September 2020, <https://www.thehindu.com/news/national/govt-has-no-data-of-migrant-workers-death-loss-of-job/article32600637.ece>, accessed 25 October 2024

Philip, A., ‘A vote too far: India’s election through the eyes of its internal migrants’, Frontline, 25 May 2024, <https://frontline.thehindu.com/politics/india-election-migrant-workers-casting-vote-problemes/article68214491.ece>, accessed 12 November 2024

Philoid, ‘Migration, Types, Causes and Consequences’, Unit 1, Chapter 2, Artificial intelligence and machine learning enabled platform to transform the contemporary teaching—learning experience, 2023, <https://philoid.com/ncert/chapter/legy202>, accessed 13 November 2024

Press Information Bureau (PIB) Delhi, ‘ECI releases an Atlas on General Elections 2019’, Press release, Government of India, 18 June 2021, <https://pib.gov.in/PressReleaseIframePage.aspx?PRID=1728136>, accessed 3 November 2024

—, ‘Home voting for eligible voters extended pan India for the first time in general elections 2024’, Press release, Government of India, 29 May 2024, <https://pib.gov.in/PressReleaseIframePage.aspx?PRID=2022053>, accessed 3 November 2024

Raj, N., Kumari, V. and Prasad, K., ‘Factors affecting migration in India: A sociological analysis’, International Journal of Humanities Social Science and Management, 4/2, (2024), pp. 974-81, <https://ijhssm.org/issue_dcp/Factors%20Affecting%20Migration%20in%20India%20%20A%20Sociological%20Analysis.pdf>, accessed 11 November 2024

Ramani, S., ‘Are NRIs likely to get postal voting rights soon?’, The Hindu, 20 December 2020, <https://www.thehindu.com/news/national/are-nris-likely-to-get-postal-voting-rights-soon/article33375087.ece>, accessed 3 November 2024

Singh, N., ‘Property Rights of Kashmiri Pandits: A Critical Evaluation of Legal and Policy Measures taken by the Indian Government’, Working Paper No. 13, Researching Internal Displacement (2021), <https://researchinginternaldisplacement.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/RID-WP13_Niketa-Singh_Kashmiri-Pandits_Dec-2021.pdf>, accessed 11 November 2024

Tata Institute of Social Sciences, ‘Inclusive Elections in India: A Study on Domestic Migration and Issues in Electoral Participation’, 6 November 2015, <https://www.shram.org/reports_pdf/eci_report.pdf>, accessed 27 October 2024

United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs (UN DESA), International Migration 2020: Highlights (New York: UN, 2020), <https://www.un.org/development/desa/pd/sites/www.un.org.development.desa.pd/files/undesa_pd_2020_international_migration_highlights.pdf>, accessed 27 October 2024

United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO), ‘For a Better Inclusion of Internal Migrants in India, Policy Brief (New Dehli: UNESCO, 2012), <https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000219173>, accessed 11 November 2024

Wadhawan N., ‘India Labour Migration Update 2018’, International Labour Organization (2018), <https://www.ilo.org/sites/default/files/wcmsp5/groups/public/%40asia/%40ro-bangkok/%40sro-new_delhi/documents/publication/wcms_622155.pdf>, accessed on 17 October 2024

About the author

Banasmita Bora, PhD, is an Assistant Professor at Christ University, Bangalore with a keen interest in election studies, governance, Indian politics, and peace and conflict. She holds a PhD from the University of Delhi. Recently, she has been part of developing various international and national training modules for the India International Institute of Democracy and Election Management. Previously, she worked at Lokniti, the Centre for the Study of Developing Societies, Delhi, conducting various national election studies. She has observed several elections for the Asian Network for Free Elections.

About this series

This case study is part of the ‘Absent Voters of South Asia’ project, which falls under the project of ‘Migrations and Elections’ that covers member states of the South Asian Council for Regional Cooperation (SAARC), such as Afghanistan, Bangladesh, Bhutan, India, the Maldives, Nepal, Pakistan and Sri Lanka.

© 2024 International Institute for Democracy and Electoral Assistance

International IDEA publications are independent of specific national or political interests. Views expressed in this publication do not necessarily represent the views of International IDEA, its Board or its Council members.

With the exception of any third-party images and photos, the electronic version of this publication is available under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 (CC BY-NC-SA 4.0) licence. You are free to copy, distribute and transmit the publication as well as to remix and adapt it, provided it is only for non-commercial purposes, that you appropriately attribute the publication, and that you distribute it under an identical licence. For more information visit the Creative Commons website: <http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/4.0>.

Design and layout: International IDEA

DOI: <https://doi.org/10.31752/idea.2024.101>

ISBN: 978-91-7671-854-4 (PDF)

ISBN: 978-91-7671-921-3 (HTML)