The Absent Voters of Bhutan

Challenges and Prospects for the Enfranchisement of Migrants

Introduction

This case study examines the enfranchisement of Bhutan’s international and internal migrants. Compared with other South Asian countries, Bhutan stands out for adopting absentee voting policies and processes that aim for greater inclusion of its absent voters. However, the legal framework governing eligibility for absentee voting imposes substantial limitations, such as strict residency requirements, property ownership restrictions and limited categories of voters eligible for postal voting, which restrict broader enfranchisement.

The study identifies key operational and logistical challenges in conducting elections in Bhutan’s mountainous and inaccessible terrain, alongside the normative and financial implications that an expansion of the current absentee voting system would entail. It also highlights cultural, social and bureaucratic barriers that deter Bhutan’s voters on the move from registering to vote, including reluctance to change one’s place of civil registration, low levels of political and democratic awareness among the population, and prevailing social norms.

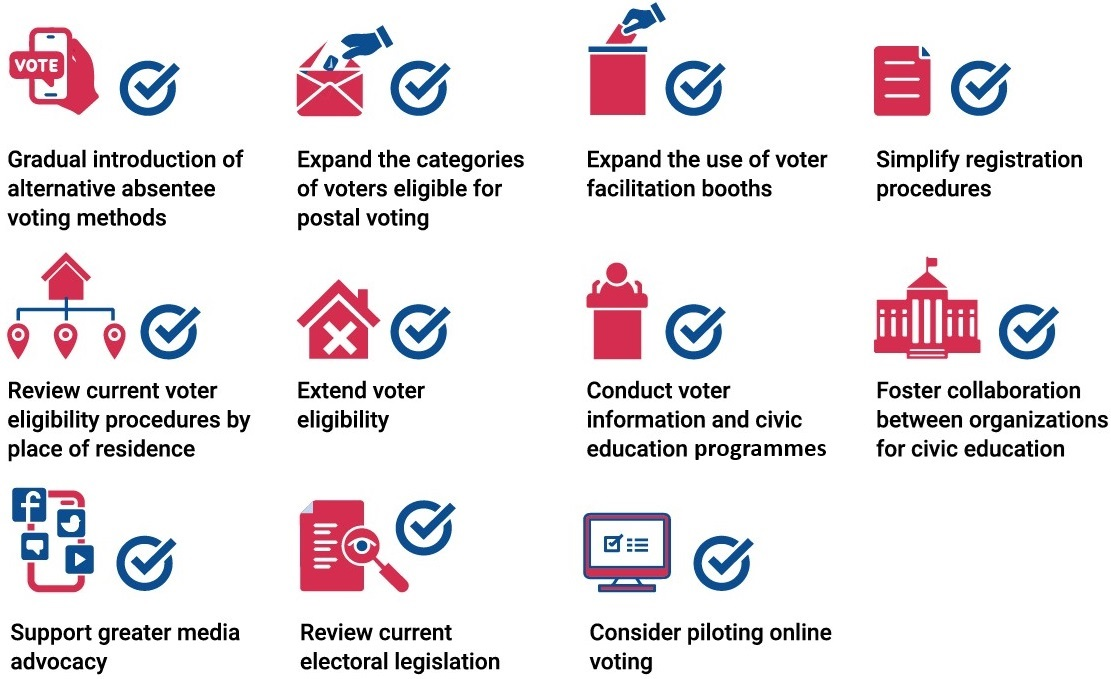

In its concluding section, the study offers recommendations to enhance and expand the enfranchisement of Bhutan’s absent voters. These include exploring alternative absentee voting methods, expanding eligibility for postal voting, simplifying civil registration procedures, removing current eligibility limitations for absentee voting, and fostering greater public electoral awareness and civic education.

1. Context and characteristics of Bhutan’s migration

Information on Bhutan’s migration is captured by various government agencies, reflecting differences and gaps in data collection methods1 and, hence, in the resulting numbers and statistics. In the nationwide censuses of 2005 and 2017, Bhutan’s National Statistics Bureau conducted an analysis of migration. The National Statistics Bureau defines as migrants those who have moved from their usual place of residence in Bhutan by crossing the border of a gewog (a block of villages) or having left the town where they had lived for a period of at least 12 months (NSB 2018a).

Bhutan’s internal migration increased as the country’s socio-economic development accelerated in the 1960s (Dhakal 1987). The country’s rates of internal migration are the highest in South Asia (Choda 2012), predominantly triggered by the development differentials between rural and urban areas. Many Bhutanese spend years living in towns in pursuit of their jobs or studies (Gosai and Sulewski 2020).

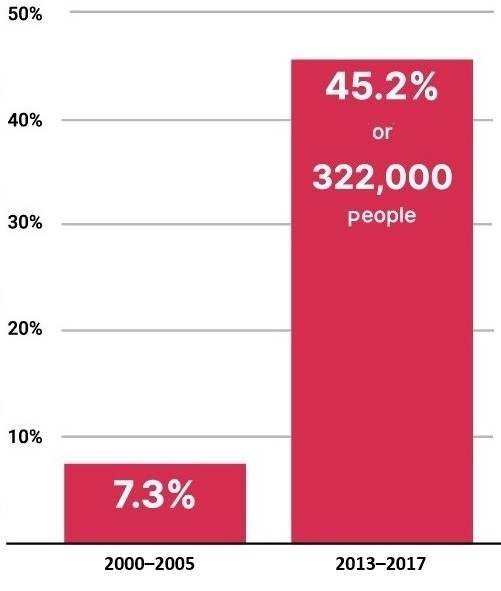

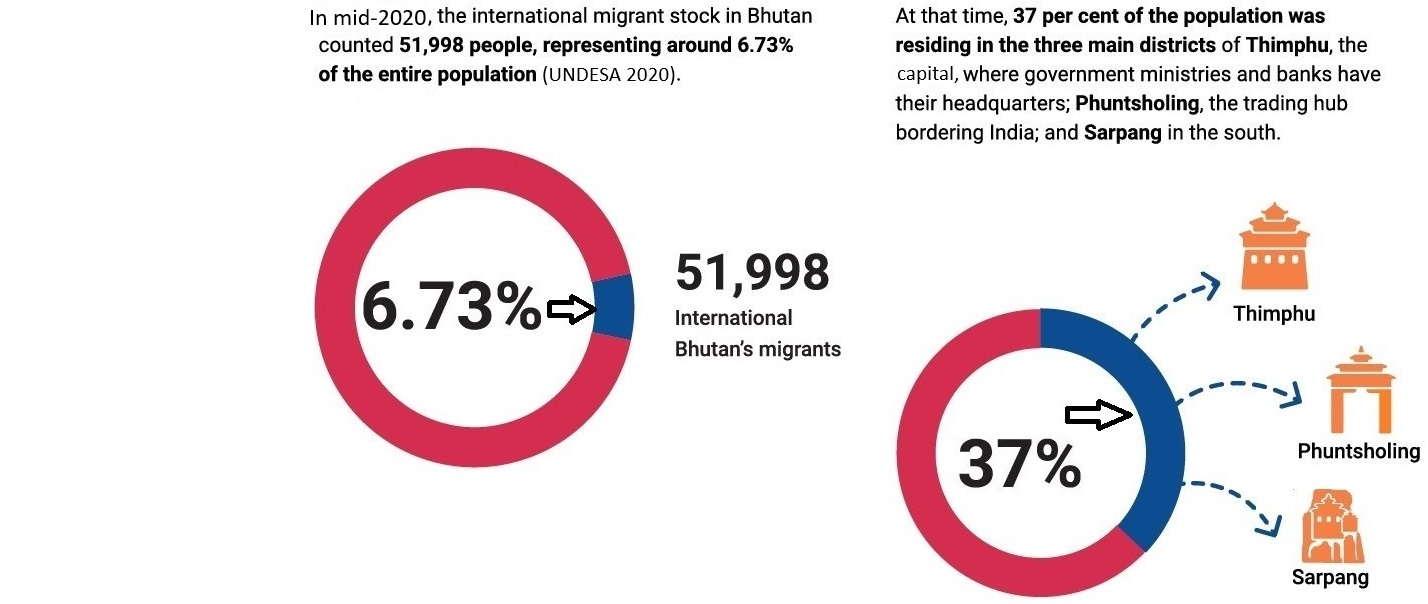

Since 1994 rural–urban migration has led nearly 40 per cent of the population to move to cities or towns, increasing the urban population by 15 per cent. In the period 2000–2005, Bhutan recorded an average annual rate of rural–urban migration of 7.3 per cent (World Bank and Royal Government of Bhutan 2019). The 2017 Census showed that nearly 322,000 people, or 45.2 per cent of the total resident population, migrated within Bhutan between 2013 and 2017 (Gosai and Sulewski 2020). At that time, 37 per cent of the population was residing in three main districts—Thimphu, the capital, where government ministries and banks have their headquarters; Phuntsholing, the trading hub bordering India; and Sarpang, in the southern part of the country (NSB 2018a).

In recent decades, internal population movements have been characterized by a shift to the western region around Bhutan’s capital. In the five years preceding the 2017 Census, around two-thirds of the gewogs and towns in central and eastern Bhutan (65.2 and 69.1 per cent respectively) experienced net population decreases due to internal migration. In 2018, an estimated 123,300 internal migrants moved between districts, representing 17.1 per cent of the total resident population. In the same year, the districts with the three largest urban centres attracted 41.1 per cent of all internal migration. Around 17 per cent of Bhutan’s total labour force resides in Thimphu (World Bank and Royal Government of Bhutan 2019; (NSB 2018b).

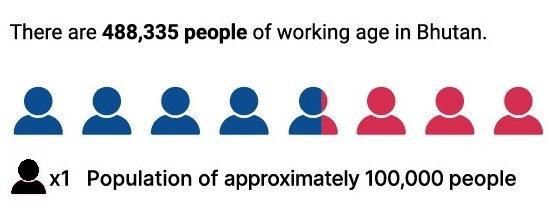

Internal migrants increase in number each year. Approximately 51.4 per cent of Bhutan’s workforce falls within the 25 to 44 year age range, reflecting a relatively young labour force characteristic of a developing economy (Ministry of Labour and Human Resources 2017). Migration for education and training occurs mainly among people aged between 10 and 24, while migration for employment reasons occurs mainly among people aged between 25 and 64, and migration for marriage is mostly concentrated in the 20–34 age group. Data shows that 31.6 per cent of the working-age population is economically active in urban areas, while 68.4 per cent of the working-age population is active in rural areas (NSB 2020).

National workforce plans that incentivize people to work on government infrastructure projects have led to mini waves of internal migration. Civil servants constitute a large proportion of Bhutan’s internal migrants. They usually remain outside their places of origin until retirement (NSB 2020).

Students of voting age are also considered internal migrants. Data published by the Education Ministry in 2019 indicated that over 12,000 students (48.6 per cent women) were enrolled in 16 higher education colleges across Bhutan, and an additional 2,000 students were enrolled in vocational institutes. Student numbers increase when private education institutes are included (Ministry of Education 2020). There are likely to be more self-financed students in Australia, India, Sri Lanka and Thailand (Drukpa 2020).

Bhutan experiences dynamic patterns of internal migration, and many people maintain links with their home village, which include paying local taxes and returning for annual spiritual events, festivals and family occasions. Projections of internal population movement foresee that 56.8 per cent of the population will be living in urban centres by 2047 (UN DESA 2019).

Although international migration from Bhutan is not significant in absolute terms, it is still noteworthy when compared with the country’s population size. In 2017, 5.4 per cent of Bhutan’s population was recorded as living abroad, many to pursue tertiary education or specialized training. As of 2023, records show Bhutanese migrating to 118 countries (Ura 2023), while information released by Bhutan’s Foreign Ministry in 2021 indicates Bhutanese in 56 countries across the globe (MFA 2021). In mid-2020, UN DESA had estimated that Bhutan had an international migrant stock of 51,998 people, representing approximately 6.73 per cent of the total population. In 2019 approximately 1,000 students of voting age were living abroad on government scholarships (46.7 per cent were women).2 Government records show 2,500 self-funded students living outside Bhutan, but actual numbers are likely to be higher (Ministry of Education 2020).

International migration from Bhutan has surged notably since 2022. Data from Paro International Airport indicates that, starting in July 2022, the monthly average of Bhutanese emigrants was approximately 3,120. This figure escalated to 5,099 in January 2023 and further to 5,542 in February 2023. Over the past eight years, a total of 50,125 Bhutanese have emigrated via Paro International Airport (Ura 2023). These records indicate those who left by air but not those who migrated overland across the southern border with India.

Push factors for international migration are the limited domestic employment opportunities, increasing unemployment and other economic reasons. In 2020, at the peak of the Covid-19 pandemic, the unemployment rate stood at 5.4 per cent3 (Business Bhutan 2021). The youth unemployment rate stood at 22.6 per cent in 2020, up from 11.9 per cent in 2019 (UNDP 2022).4

Recent research and media reports confirm that Bhutanese citizens are increasingly seeking employment opportunities abroad, prompted by generous visa offers from a few countries. They are pulled by the prospects of higher incomes, better economic opportunities, financial security and access to better education—and what they consider to be a more secure future (Ura 2023; Shivamurthy 2023). An Asian Development Bank study (2018) found more than 6,000 Bhutanese (50 per cent women) living in India’s border town of Jaigaon because of unaffordable housing and living costs in Phuntsholing, the town in Bhutan bordering India.

In 2020 Bhutan’s government—as part of its Covid-19-linked repatriation efforts—registered those international migrants who were willing to return5 to the country.

Government sources acknowledge the difficulties in obtaining accurate figures on pandemic-related returnees, as most international migrants do not register their status. During the pandemic, Bhutanese returned from Africa, Europe, other South and South-east Asian countries, and the United States. As of May 2021, almost 13,000 citizens had officially returned to Bhutan from 68 countries (Prime Minister’s Office 2021).

Unlike other South Asian countries, the contribution of financial remittances to Bhutan’s gross domestic product is minimal, ranging from 1.5 per cent to 2.7 per cent in 2021 (World Bank n.d.). Nonetheless, remittances help to stabilize the country’s balance of payments. In 2019, remittances from Australia were the most significant, at AUD 31 million (USD 20.5 million), followed by remittances from the USA at USD 19 million (Royal Monetary Authority of Bhutan 2022).

2. Typologies of migration within and outside Bhutan

Internal migration within Bhutan had become increasingly prevalent until pandemic-related travel restrictions were lifted in 2022, after which more citizens began to migrate internationally. There are three types of migration in Bhutan:

- Regular migration. Bhutanese can move freely within the country to migrate internally. The state also resettles landless people by providing them with farmland in various locations. This practice facilitates regular migration within the country (Integral Human Development 2020). As people customarily spend many years away from their places of origin, such movement can be regarded as regular migration. An increasingly educated populace is also moving from rural to urban centres, pulled by better services and facilities as well as employment and economic opportunities (NSB 2018b).

- Irregular migration. The Covid-19 pandemic led to inflows of irregular internal migration. Prolonged lockdowns affected businesses, resulting in a loss of employment. By mid-2021 official records showed that about 4,000 people, including students, had left Phuntsholing to resettle in the Thimphu and Paro districts (Gosai and Sulewski 2023).

- Circular migration. Traditional population mobility occurs in districts where people migrate with their livestock in winter to warmer areas. The clergy also migrate seasonally, and a small, regular core of pilgrims migrate either within Bhutan or to neighbouring India and Nepal to study for extended periods. This type of migration fluctuates, and precise figures are unavailable.

Common destinations for students are South Asia (Bangladesh, India, Sri Lanka) and South-east Asia (Malaysia, Singapore, Thailand). In 2016 students made up 82.2 per cent of Bhutanese who had temporarily entered Australia. Only 10.6 per cent were migrant workers (ABS 2019).

3. Status of the electoral enfranchisement of Bhutan’s migrants

The Constitution of Bhutan guarantees the right to suffrage, outlines provisions governing the conduct of elections (article 23) and establishes the Election Commission of Bhutan (ECB) (article 24). Such provisions confer both rights and duties on citizens (articles 4 and 5), while article 7 provides them with the right to vote. Voting is not compulsory, but the penalties for failing to do so are stringent, although their enforcement presents some challenges.6 The Elections Act regulates the electoral process. Article 100 establishes that ‘citizens shall be entitled to be registered as a voter for a constituency if the person is 18 years or more and is registered in the civil registry of a particular constituency for not less than one year’.

The ECB has gradually expanded absentee voting provisions at each successive parliamentary or local government election, gradually facilitating access to the franchise to vulnerable categories of voters, including Bhutan’s internal and international migrants. For the 2018 National Council and National Assembly elections and during the Covid-19 pandemic,7 the ECB tested an absentee postal voting system and piloted the use of electronic voting machines in mobile booths to facilitate the enfranchisement of those over the age of 65 or with underlying health conditions—categorized as vurnelable. These absentee voting measures had some success. Innovative approaches, such as the establishment of ‘facilitation booths’,8 allowed voters to cast their ballots in their actual place of residence rather than their place of civil registration (ECB 2023).

For the 2018 parliamentary elections, the ECB covered the costs of the postal votes mailed to international migrants in their country of residence abroad. To support this effort, the government established focal offices in diplomatic missions or in select locations where large numbers of these migrants resided, and the relevant government agencies also deployed officials abroad. The ECB also made significant efforts to reach voters residing abroad through social media. However, due to the demands of work or study overseas, not all voters residing abroad were able to take advantage of the absentee voting services provided to them (ECB 2020).

In 2023 the ECB announced the discontinuation of the absentee voting services introduced for the 2018 elections and during the pandemic (Dolkar 2023a). This change restricted eligibility for postal voting to the limited categories of voters outlined in article 331 of the Elections Act—specifically, civil servants, armed forces officials, government trainees, students and officials on election duty, along with their spouses. Additionally, special categories of voters, such as long-term hospital patients, persons with disabilities and prisoners, remain eligible to vote by post. However, those working overseas who are not part of Bhutan’s civil service are not eligible.

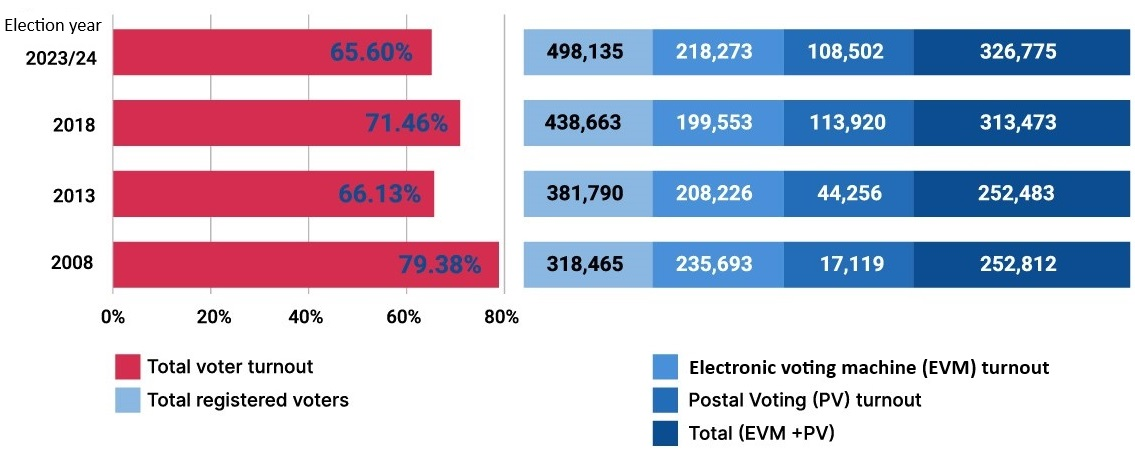

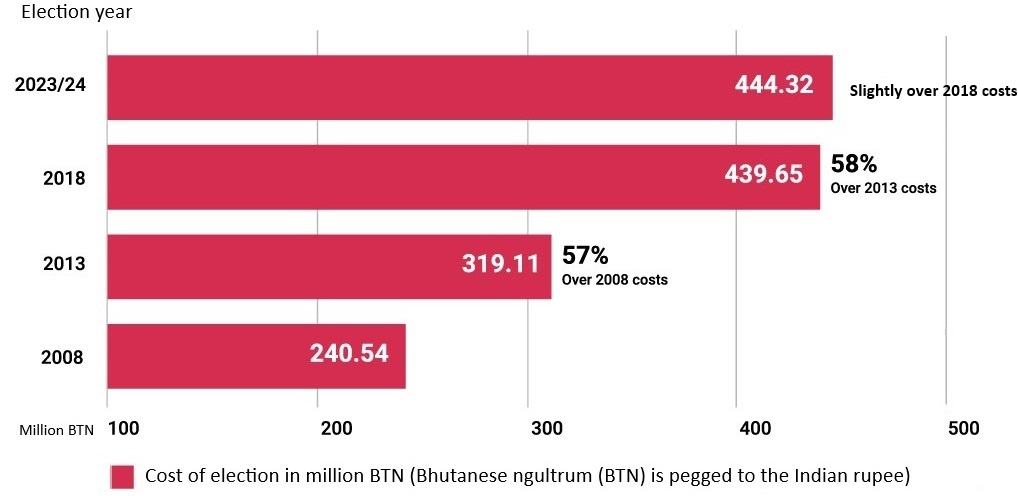

The 2023 National Council elections recorded a voter turnout of 55 per cent, compared with the 68 per cent voter turnout for the 2021 local government elections, when many postal voting and facilitation services were still available. Voter turnout for Bhutan’s 2018 parliamentary elections was 71.46 per cent, ranking it fourth among South Asian countries.9 Voter turnout for National Council elections traditionally tends to be lower than for elections to the National Assembly.10

In the 2023 National Assembly elections, those working in tourism and state-owned enterprises were also added to the categories of those eligible to vote by post. Employees from these categories can cast their ballot by postal vote to avoid disrupting essential services on election day (Dolkar 2023b).

4. Challenges to the electoral enfranchisement of Bhutan’s absent voters

While the past four parliamentary electoral cycles have seen attempts by the ECB to expand the franchise for Bhutan’s absent voters, several challenges to their broader enfranchisement persist:

- Legal restrictions on voter eligibility. To qualify as voters, in addition to residence requirements, citizens of a thromde (city/town) must also own landed property.11 This requirement disqualifies most urban residents from voting in the place where they reside to a significant extent, and are tied to their place of registration—usually the place they were born. For example, while Bhutan’s capital, Thimphu, has a population of over 110,000 people, only 8,000 of them are registered to vote there (barely 7 per cent of the city’s population); similarly, fewer than 1,000 residents of Phuntsholing, with a population of almost 28,000, are registered to vote there (3.3 per cent of the city’s population); and only 1,600 of the 10,000 residents of Geylephug are registered to vote there (15.6 per cent).12 These restrictions on the right to vote constitute a barrier to inclusive democracy in Bhutan, posing significant challenges, particularly in towns bordering India, where large numbers of residents do not own landed property and hence cannot vote at their place of residence; they have vote in the villages where they were born or are registered.

- Operational and logistical challenges. Bhutan’s geographic boundaries in mountainous terrain make it complex and costly to conduct elections. In addition, the absence of an accurate and reliable address system, especially in the towns, poses fundamental problems for postal voting. Many Bhutanese pick up their mail from the post office, have it delivered to their place of work or have it sent to a working member of a family.

- Financial costs. The cost of holding elections increased by 58 per cent between 2013 and 2018. In particular, the use of mobile facilitation booths implies additional setup, logistical and manpower costs. This led to a 42 per cent increase in the overall cost of holding the 2023 National Council elections. The ECB has taken various measures to lower the cost of elections, such as reducing the number of polling booths from 866 to 811 for the 2023 National Assembly elections (Wangchuk 2023).

- Geographic barriers. A voter’s physical absence from their place of registration and voting is a significant barrier to the enfranchisement of internal absent voters. The European Union Election Observation Mission (2008) for the 2008 National Assembly elections reported that a ‘significant number of voters, who reside in a different constituency than that of their civil registration, are not eligible for postal voting, and have to travel long distances to vote, with distances as far as three days by car’. The challenges presented by distance in 2008 remain a valid observation today, despite improvements to the road networks. The lack of readily available transport services continues to present a voting accessibility barrier, especially for the elderly, persons with disabilities and those working in the private sector who cannot afford to close their businesses for up to a few days for the time it takes to travel to vote. In general, Bhutanese voters find it demanding to travel long distances to vote. Doing so can entail multiple journeys—for example, once for the National Council election and then twice more for the National Assembly election (once for the primary and then again for the final election). Voting multiple times in relatively close succession is both costly and time-consuming for citizens. Reaching international migrants is also challenging. During the 2021 National Assembly by-elections, disruption to postal services caused by the pandemic meant that migrants in Australia and the USA had to rely on costly international courier services to mail—at their own expense—their ballot papers back to the ECB (MFA 2021). While the ECB covered the cost of returning the ballots, they had to be distributed to voters by the focal government agency abroad. Furthermore, not all overseas voters live in countries where Bhutan maintains a diplomatic mission. Voters in such places had to incur postage costs for receiving their postal ballots. This coupled with lengthy procedures for applying for, completing and returning the postal ballots posed a significant deterrent to voting from abroad.

- Cultural, social and bureaucratic barriers. Bhutanese feel a strong connection to their places of origin and are generally reluctant to change their civil registration, even though they are legally able to do so. The barriers to voting in their place of residence without civil registration further reinforce people’s connection with their families and village communities (Kinley 2017). In 2008 the EU Election Observation Mission highlighted the ‘bureaucratic, and somewhat cumbersome process’ of changing civil registration as a significant barrier to voting. Attitudinal barriers to electoral participation include the generally low levels of political interest, commitment and democratic awareness among Bhutan’s population (BCMD 2019). As democracy was introduced in Bhutan only in 2008, more time and a change in mindset are needed for a deeper understanding and more meaningful embracement of democratic values and civic duties by its population.

- Insufficient civic awareness. Like in any young democracy, citizens of Bhutan are only beginning to learn that their responsibilities involve the right and duty to choose their political leadership, provide constructive feedback to their government and take an interest and actively engage in their community’s political13 and societal affairs. Furthermore, the prevailing social norm that educational institutions, civil society organizations and the civil service in Bhutan should be ‘apolitical’ has led to a widespread assumption that such entities should avoid engaging in any political activity. This is often misunderstood as not talking about politics, not discussing public policy issues and not being involved in any way with elections (Kuensel 2018). Often, this acts as a barrier for citizens to assess the performance of their political leadership and hence to hold them accountable for their work.

5. Prospects for the electoral enfranchisement of Bhutan’s absent voters

Several key recommendations can be drawn from the analysis of Bhutan’s absentee voting system which the ECB could consider for its ongoing efforts to expand the enfranchisement of its absent voters. Consideration could be given to the following:

- reviewing current electoral legislation and voting procedures to identify ways to enfranchise Bhutan’s absent voters more effectively, including the necessary legal and procedural amendments to expand the limited categories of voters currently eligible for postal voting;

- as Bhutan’s internal and international migration trends are likely to continue growing, gradually improving postal voting to help maintain a healthy voter turnout among its sizeable absent population;

- exploring the gradual introduction of alternative absentee voting methods to allow voters who are away from their place of registration, whether within the country or abroad, to cast their ballots from their current place of residence;

- testing alternative absentee voting methods and increasing the use of information and communications technology to pilot an online voting system;14

- maximizing the current use of voter facilitation booths in larger towns where significant numbers of internal migrants reside;

- simplifying voter registration procedures, particularly for internal migrants and those who are less literate, those working in small businesses and persons with disabilities;

- reviewing current voter eligibility procedures to allow access to the franchise in a voter’s place of residence, as the current procedures limit eligibility to vote to where a person was born rather than where that person currently lives;15

- extending voter eligibility in town elections to long-term residents who do not own land or property;16

- conducting greater voter information and civic education efforts through programmes (in several languages) tailored to a diverse population—notably the educated, the rural, the young and the civil servants;

- fostering more effective collaboration with and between civil society organizations and community-based organizations to overcome knowledge and information gaps and deepen civic education among diverse segments of Bhutan’s society;

- engaging universities and educational institutions in voter information and civic education, as they have a captive, youthful population who are both potential migrants and potential voters; and

- supporting greater media advocacy, educational and topical programmes and reporting between elections and prioritizing the use of online services and social media platforms to connect international migrants with political and electoral developments at home and encouraging them to vote.

References

Asian Development Bank, ‘Phuntsholing Township Development Project: Poverty and Social Analysis’, May 2018, <https://www.adb.org/sites/default/files/linked-documents/50165-002-sd-07.pdf>, accessed 26 October 2024

Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS), ‘Insights from the Australian Census and Temporary Entrants Integrated Dataset’, Reference period 2016, Released 14 February 2019, <https://www.abs.gov.au/statistics/people/people-and-communities/temporary-visa-holders-australia/2016>, accessed 12 November 2024

Bhutan Centre for Media and Democracy (BCMD), ‘Bhutan’s Democracy: A Decade On’ [film], 25 March 2019, <https://bcmd.bt/documentary-on-bhutans-democratic-journey/>, accessed 12 November 2024

Business Bhutan, ‘Unemployment rate hits an all-time high of 5% in 2020’, 5 April 2021, <https://businessbhutan.bt/unemployment-rate-hits-an-all-time-high-of-5-in-2020/>, accessed 12 November 2024

Choda, J., ‘Rural out-migration scenario in Khaling Gewog, Trashigang, Eastern-Bhutan’, Journal of Agroforestry and Environment, 6/2 (2012), pp. 29–32, <https://pas.cseas.kyoto-u.ac.jp/activity/HP_SPIRITS/Brahmaputra/data/JAE_ALL/ASFBpdf/12.AFSB6(2)pdf/7.%20Choda.pdf>, accessed 26 October 2024

Choki, P., ‘The increasingly important role of the National Council over the last 15 years’ The Bhutanese, 8 April 2023, <https://thebhutanese.bt/the-increasingly-important-role-of-the-national-council-over-the-last-15-years/>, accessed 12 November 2024

Dhakal, D. N. S., ‘Twenty-five years of development in Bhutan’, Mountain Research and Development, 7/3 (1987), pp. 219–21, <https://doi.org/10.2307/3673197>

Dolkar, D., ‘NA elections to cost Nu 444M’, Kuensel, 4 November 2023a, <https://kuenselonline.com/na-elections-to-cost-nu-444m/>, accessed 12 November 2024

—, ‘Voter turnout decreases as compared to third NA elections’, Kuensel, 2 December 2023b, <https://kuenselonline.com/voter-turnout-decreases-as-compared-to-third-na-elections/>, accessed 12 November 2024

Drukpa, U., ‘1,057 out of 3,930 Bhutanese students studying abroad impacted by closures’, The Bhutanese, 21 March 2020, <https://thebhutanese.bt/1057-out-of-3930-bhutanese-students-studying-abroad-impacted-by-closures/> accessed 12 November 2024

Election Commission of Bhutan (ECB), ‘Statistical Information on Bhutan’s Third Parliamentary Elections 2018’, 24 September 2020, <https://www.ecb.bt/statistical-information-on-bhutans-third-parliamentary-elections-2018/>, accessed 12 November 2024.

—, ‘Final Results for National Council Elections, 2023’, 20 April 2023, <https://www.ecb.bt/provisional-results-for-national-council-elections-2023/>, accessed 26 October 2024

European Union Election Observation Mission, ‘Bhutan 2008: Final Report on the National Assembly Elections, 24 March 2008’, 21 May 2008, <https://aceproject.org/ero-en/regions/asia/BT/bhutan-final-report-national-assembly-elections/view>, accessed 26 October 2024

Gosai, M. and Sulewski, L., ‘Internal migration in Bhutan’, in M. Bell, A. Bernard, E. Charles-Edwards and Y. Zhu (eds), Internal Migration in the Countries of Asia: A Cross-national Comparison (Cham, Switzerland: Springer, 2020),<https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-44010-7_12>

—, ‘Attraction and detraction: Migration drivers in Bhutan’, in S. I. Rajan (ed.), Migration in South Asia. IMISCOE Research Series (Cham, Switzerland: Springer, 2023), <https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-34194-6_8>

Gyeltshen, D., ‘Repatriation of Bhutanese during COVID-19 pandemic: The unspoken economic burden of COVID-19 on the Bhutanese Government’, Asia Pacific Journal of Public Health, 34/1 (2022), pp. 123–24, <https://doi.org/10.1177/10105395211053735>

Integral Human Development, ‘Migration Profile – Bhutan’, Migrants & Refugees Section, 2020, <https://migrants-refugees.va/it/wp-content/uploads/sites/3/2022/05/2022-CP-Bhutan.pdf>, accessed 12 November 2024

International IDEA, Voter Turnout Database, [n.d.], <https://www.idea.int/data-tools/data/voter-turnout-database>, accessed 26 October 2024

Kinley, ‘Socio-economic Status and Electoral Participation in Bhutan’, Druk Journal, 2017, <https://drukjournal.bt/wp-content/uploads/2021/06/Socio-economic-status-and-Electoral-Participation-in-Bhutan.pdf>, accessed 12 November 2024

Kuensel, ‘Being apolitical’, 17 August 2018, <https://kuenselonline.com/being-apolitical/>, accessed 12 November 2024

Ministry of Education, Royal Government of Bhutan, ‘Annual Education Report 2019-2020’, Policy and Planning Division, June 2020, <http://www.education.gov.bt/wp-content/uploads/2020/07/Annual-Education-Report.pdf>, accessed 12 November 2024

Ministry of Foreign Affairs and External Trade (MFA), Royal Government of Bhutan, ‘Notification on LG elections for postal voters’, Royal Bhutanese Embassy, New Delhi, India, 30 November 2021, <https://www.mfa.gov.bt/rbedelhi/notification-on-lg-elections-for-postal-voters/>, accessed 12 November 2024

Ministry of Labour and Human Resources, ‘Labour Force Survey Report 2016’, Department of Employment and Human Resources, Labour Market Information and Research Division, 2017, <https://www.moice.gov.bt/wp-content/uploads/2017/12/Labour-Force-Survey-Report-2016.pdf>, accessed 12 November 2024

National Statistics Bureau (NSB) of Bhutan, Rural-Urban Migration and Urbanization in Bhutan (Thimphu, Bhutan: National Statistics Bureau of Bhutan, 2018a), <https://www.nsb.gov.bt/rural-urban-migration-and-urbanisation-in-bhutan-2/>, accessed 26 October 2024

—, 2017 Population and Housing Census of Bhutan, Royal Government of Bhutan, 2018b, <https://www.nsb.gov.bt/wp-content/uploads/dlm_uploads/2020/07/PHCB2017_wp.pdf>, accessed 12 November 2024

—, Statistical Yearbook of Bhutan 2020 (National Statistics Bureau of Bhutan, 2020), <https://www.nsb.gov.bt/wp-content/uploads/dlm_uploads/2020/11/SYB_2020_Latest.pdf>, accessed 26 October 2024

Prime Minister’s Office, ‘State of the Nation’, Sixth Session, Third Parliament of Bhutan, Dr Lotay Tshering, Prime Minister, Royal Government of Bhutan, 24 December 2021, <https://www.pmo.gov.bt/wp-content/uploads/2019/09/State-of-the-nation-2021.pdf>, accessed 12 November 2024

Royal Government of Bhutan, ‘Bhutan National Workforce plan (2016-22)’, (Thimphu, Bhutan: Royal Monetary Authority of Bhutan, 2022), (Acc. R 213), 2016, <http://library.cnr.edu.bt/cgi-bin/koha/opac-detail.pl?biblionumber= 6181&shelf browse_itemnumber=8531>, accessed 26 October 2024

Royal Monetary Authority of Bhutan, Annual Report 2022, <https://ypfsresourcelibrary.blob.core.windows.net/fcic/YPFS/RMA-Annual-Report-2022.pdf>, accessed 26 October 2024

Shivamurthy, A. G., ‘Assessing Bhutan’s migration trends and policies’, Observer Research Foundation, 31 March 2023, <https://www.orfonline.org/expert-speak/assessing-bhutans-migration-trends-and-policies>, accessed 26 October 2024

United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs (UN DESA), ‘International Migrant Stock 2019’, POP/DB/MIG/Stock/Rev.2019, August 2019, <https://www.un.org/en/development/desa/population/migration/data/estimates2/docs/MigrationStockDocumentation_2019.pdf>, accessed 26 October 2024

United Nations Development Programme (UNDP), ‘Flattening youth unemployment curve in Bhutan’, press release, 18 March 2022, <https://www.undp.org/bhutan/press-releases/flattening-youth-unemployment-curve-bhutan>, accessed 12 November 2024

Ura, K., ‘Migration of Bhutanese’, Kuensel, 20 May 2023, <https://kuenselonline.com/migration-of-bhutanese/>, accessed 26 October 2024

Wangchuk, R., ‘4th NA elections will not be expensive’, Kuensel, 16 August 2023, <https://kuenselonline.com/4th-na-elections-will-not-be-expensive/>, accessed 26 October 2024

World Bank, World Bank Open Data, ‘Personal remittances, received (% of GDP) – Bhutan’, [n.d.], <https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/BX.TRF.PWKR.DT.GD.ZS?locations=BT>, accessed 26 October 2024

World Bank and Royal Government of Bhutan, Bhutan Urban Policy Notes (World Bank Group, 2019), <https://www.moit.gov.bt/wp-content/uploads/2019/06/Bhutan-Urban-Policy-Notes.pdf>, accessed 26 October 2024

About the author

Siok Sian Pek-Dorji is the founder and former Executive Director of the Bhutan Centre for Media and Democracy and currently serves as an advisor to the centre. She is a print and broadcast journalist. She has moderated, facilitated and organized many training sessions and events and is the author of numerous articles highlighting urgent social issues.

About this series

This case study is part of the ‘Absent Voters of South Asia’ project, which falls under the project of ‘Migrations and Elections’ that covers member states of the South Asian Council for Regional Cooperation (SAARC), such as Afghanistan, Bangladesh, Bhutan, India, the Maldives, Nepal, Pakistan and Sri Lanka.

© 2024 International Institute for Democracy and Electoral Assistance

International IDEA publications are independent of specific national or political interests. Views expressed in this publication do not necessarily represent the views of International IDEA, its Board or its Council members.

With the exception of any third-party images and photos, the electronic version of this publication is available under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 (CC BY-NC-SA 4.0) licence. You are free to copy, distribute and transmit the publication as well as to remix and adapt it, provided it is only for non-commercial purposes, that you appropriately attribute the publication, and that you distribute it under an identical licence. For more information visit the Creative Commons website: <http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/4.0>.

Design and layout: International IDEA

DOI: <https://doi.org/10.31752/idea.2025.100>

ISBN: 978-91-7671-853-7 (PDF)

ISBN: 978-91-7671-920-6 (HTML)