The Absent Voters of Bangladesh

Challenges and Prospects for the Enfranchisement of Migrants

Introduction

This case study explores Bangladesh’s migration trends, highlighting its status as the sixth-largest source of international migrants in 2020 and underscoring the significant impact of migratory movements on the nation. It then examines the electoral enfranchisement of Bangladesh’s absent voters, revealing a stark dichotomy: while legal provisions formally grant overseas voters the right to vote, complex and restrictive postal voting procedures prevent them from exercising this right in practice.

The study concludes by outlining potential reforms to enhance electoral participation among absent voters. These include revising electoral frameworks, simplifying absentee voting procedures, and possibly introducing online voting systems and in-person voting at diplomatic missions. Finally, the case study recognizes that the enfranchisement of Bangladesh’s absent voters ultimately depends on addressing operational challenges and restoring trust in a democratic process increasingly compromised by deep political polarization, electoral irregularities and political violence.

Box 1. Political update August 2024

On 5 August 2024 a student-led uprising brought down Bangladesh’s government led by Prime Minister Sheikh Hasina. After 15 years in power, the unexpected and rapid fall of her increasingly authoritarian and repressive government suddenly opens the door to hopeful change and, possibly, to a potential new democratic chapter for the country, which would need comprehensive electoral reform. Among the numerous election integrity issues to be addressed, such reform could also finally give a voice to Bangladesh’s absent voters.

1. Bangladesh’s migration: Context and characteristics

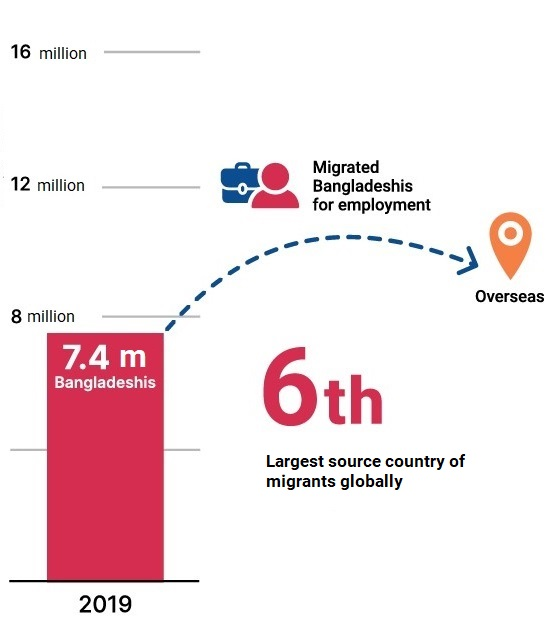

In 2020 Bangladesh ranked as the world’s sixth-largest country of origin for international migrants, confirming migration as one of the country’s defining features. In 2019 nearly 5 per cent of its population, or 7.4 million citizens, were living and working overseas (UN DESA 2020; IOM 2020). Between 1976, when the Government of Bangladesh began to document emigration flows, and September 2023, over 15.7 million Bangladeshis were recorded as having migrated overseas for employment. The vast majority of these migrants were men, but emigration on the part of women and girls began to be formally documented only in 1991. By 2020 nearly 1 million women had migrated overseas in pursuit of employment opportunities. The number and proportion of women migrants have gradually increased in the past decade (BMET n.d.). Precise estimates of the numbers of international migrants are complicated by the fact that returning migrants are not formally recorded.

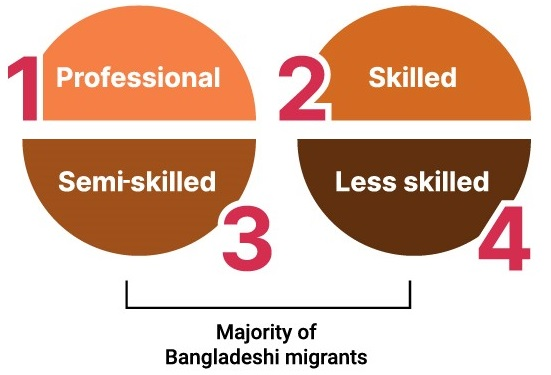

The national Bureau of Manpower, Employment and Training classifies Bangladesh’s migrant workers into four categories—professionals, skilled workers, semi-skilled workers and less-skilled workers. The majority of Bangladeshi migrants are in the less-skilled and semi-skilled categories. These numbers, however, represent only those migrants who travel overseas for work using formal, documented channels. Many Bangladeshis migrate using irregular or informal channels, or travel on student visas and tourist visas that are—at least initially—not intended for work.

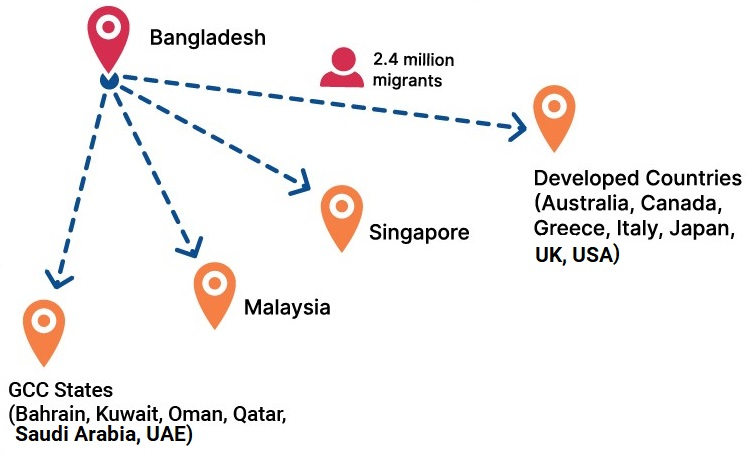

Today, the main destinations for Bangladeshi migrant workers are oil-rich countries of the Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC), notably Bahrain, Kuwait, Oman, Qatar, Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates, as well as South-east Asia, with Malaysia and Singapore as the main destinations. In addition, an estimated 2.4 million migrants have permanently settled in developed countries spanning from Australia to Canada, Greece, Italy, Japan, the United Kingdom and the United States (Monem 2017).

The government’s inability to provide adequate productive employment opportunities for all citizens has been one of the main push factors for Bangladesh’s international migration. In 2013 the youth unemployment rate was 10.3 per cent, and young women were almost four times as likely to be unemployed than young men, with respective unemployment rates of 22.9 and 6.2 per cent. The proportion of young people not in employment, education or training in the same year was 41 per cent, among the world’s highest (International Labour Office 2016).

International labour migration therefore provides vital relief in the labour market and support to the domestic economy. Remittances from abroad play an important role in Bangladesh’s economy as a leading source of foreign exchange. In 2020 the country received USD 21.75 billion through remittances, which was 6.6 per cent of its gross domestic product (Abrar 2021). Remittances have widespread and positive impacts on recipient households, improving nutrition, living standards, housing, education and healthcare, as well as reducing poverty and providing social security and investment opportunities (Barai 2012). The migration of women has also helped to transform gender relations in the country (Dannecker 2005).

However, many temporary migrant workers, especially those based in GCC countries, face exploitative recruitment and employment practices (Azad 2019: 130). Numerous reports also document physical and sexual exploitation of female migrants who work as domestic workers (Tasneem 2020). There is currently little pressure on host states from the Government of Bangladesh to protect or improve the living conditions of its migrants.

As the voices of Bangladesh’s absent voters continue to be silent, their political enfranchisement could empower them to make demands on their government to intervene on their behalf to protect their basic human rights.

Rates of internal migration are also high in Bangladesh, generally involving urban-to-urban or rural-to-urban migration movements. The capital, Dhaka, is the primary destination for both urban–urban and rural–urban migration (Hasan 2019). According to the Bangladesh Bureau of Statistics (BBS), the net internal migration rate is 145.2 persons per thousand population (BBS 2019: 100).

While international migration is overwhelmingly induced by prospects of better employment opportunities, the reasons for internal movement vary. The BBS records the leading factors for internal population movements as matrimonial, farming-related, employment, education, natural disasters (such as floods and river erosion) and the need or desire to live with family (BBS 2019).

Bangladesh is prone to a vast array of environmental hazards—storms, drought, floods, salinization and riverbank erosion—that often lead to loss of livelihood in rural areas, which in turn triggers and incentivizes internal migration flows. In addition, seasonal food scarcity in the northern parts of Bangladesh, known as monga, leads young men to migrate to seek employment in urban areas and better-off villages (Martin et al. 2017).

2. Status of the electoral enfranchisement of Bangladesh’s absent voters

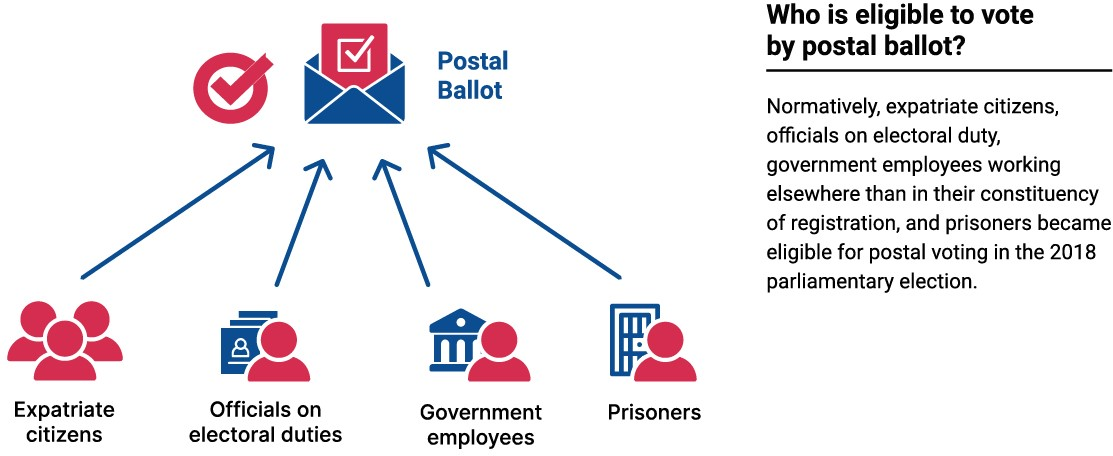

Normatively, Bangladesh’s absent voters—both international and internal migrants—are eligible to vote in elections in Bangladesh by postal ballot. A lack of information, substantial operational complexities and logistical challenges, however, make it impossible in practice for the country’s absent voters to exercise their normatively entrusted right to vote under the prescribed absentee voting processes.

Section 27 of the 1972 Representation of the People Order (Presidential Order No. 155 of 1972) entitles Bangladeshis living overseas to vote in elections. Expatriate Bangladeshis have long advocated and campaigned for their right to vote in national elections, but the necessary amendments to the law were made only in the 2013 Representation of the People (Amendment) Act (Act No. LI of 2013). This law allows ‘a Bangladeshi voter living abroad’ to cast a postal ballot.1

In addition to expatriate citizens, election officials and government employees working outside their constituency of registration and prisoners are also eligible for postal voting. However, other absentee voters, such as internal migrants who have moved away from their constituency of registration but have not registered in a new one, are not able to vote by post. Any person who has moved to a different constituency from that of their usual place of residence is required to register as a voter in the new constituency and vote there. In practice, however, the legislation excludes millions of temporary and seasonal internal migrants from the electoral franchise, leaving them with only the option to travel to their constituency of registration during the election and vote there.

Out-of-country voting (OCV) provisions that would enable, at least in theory, international migrants to vote from abroad were first introduced by the Bangladesh Election Commission (BEC) for the 2018 parliamentary election. On that occasion, the BEC outlined, in a circular sent to all embassies and diplomatic missions, qualification requirements and complex procedures to apply for, receive and return an OCV postal ballot, as follows:

- To be able to vote from abroad, voters must hold a national identity document (NID) and provide the address of their place of original residence in Bangladesh in the constituency where they were last registered to vote before migrating.

- Voters must apply for an OCV postal ballot to the district returning officer for the constituency where they were last registered to vote before migrating. Such an application must include the voter’s NID number, their address as entered on the NID and an overseas address.

- On receipt of an application, the returning officer, having ascertained the voter’s eligibility, sends a postal ballot, along with a return envelope, to the voter’s address overseas. The outer envelope includes the voter’s name, constituency name and serial number on the voter list.

- After having received the postal vote at their overseas address, and having marked the ballot paper, voters must return it by post to the returning officer. To ensure that voting is conducted through the proper postal vote process, the postal ballot paper must include a certificate of posting issued by a post office official, and the certificate must bear a rubber stamp seal (Shaikh 2018).

- To be counted, the postal ballot must be received by the returning officer by the date of the elections, as ballots received after polls have closed are not counted.

These procedural and operational problems, as well as a lack of information, persisted in Bangladesh’s 12th parliamentary elections, held in January 2024, de facto continuing to deny the right to vote to millions of absent voters (Majumdar 2024).

3. Challenges for the electoral enfranchisement of Bangladesh’s absent voters

While OCV is normatively established, several procedural complexities, a lack of information and operational shortfalls make its effective implementation impossible in practice, de facto undermining the effective participation of Bangladesh’s absent voters in their country’s elections.

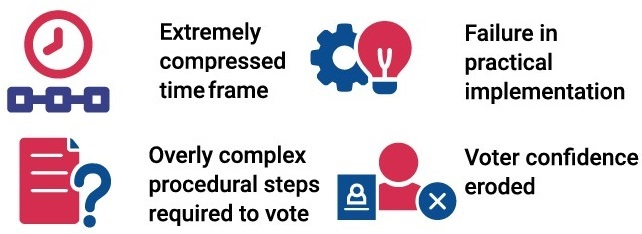

While expansion of the franchise through the inclusion of Bangladesh’s absent voters was a positive development, its implementation does not appear to have been given proper consideration as to the procedural complexities, the operational deadlines and their implications, and the public information requirements.

The procedural complexities of postal voting and the operational timeline required to make OCV effective, meaningful and a reality are highly restrictive. Overseas voters, to be able to avail themselves of the established OCV system and to comply with its procedural complexities and enfranchisement requirements, need to be informed in time and well in advance.

The extremely compressed time frame for complying with postal voting requirements presents a major challenge not only for absent voters but also for the BEC, as ballot papers can be printed only after the candidate registration process has been completed and election symbols allocated, and these operations have an impact on the timing of the OCV process.

Advocacy campaigns for expatriate voting originate mainly from migrants living in established democracies such as the USA and the UK, where some expatriate organizations actively advocate for their voting rights.2

An additional challenge is the political controversy surrounding the enfranchisement of international migrants holding dual citizenship. Many of the 2.4 million migrants residing in developed countries have acquired citizenship in those countries. While they have maintained their Bangladeshi citizenship and, hence, are permitted to vote in elections in both their host country and their country of origin, some political parties have expressed concerns3 about extending voting rights to them.

Some internal migrants asked the BEC to allow them to vote by email. Such requests, however, could not be considered, as electoral legislation allows absentee voting by postal vote only (BBC Bengali News 2018). There was only one application for a postal ballot from an absent voter in a different district of the country in 2018 (Chaity 2018).

Finally, the problems encountered in operationalizing legally established OCV provisions must be seen in the wider context of declining confidence in democracy and the integrity of elections in Bangladesh. According to Human Rights Watch (2019), the 2018 general election was marred by irregularities, fraud and widespread violence involving ‘attacks on opposition party members, voter intimidation, vote rigging, and partisan behaviour by election officials in the pre-election period and on election day’ (Ganguly 2019). In that election, the ruling Awami League’s coalition, led by Sheikh Hasina, secured 288 of the 300 seats in parliament, a landslide victory that ensured a secure third term for her administration.

Before Prime Minister Hasina’s regime was overthrown, the Bangladeshi electorate’s confidence in its ability to change a government through the vote had been eroded. Unless genuine and meaningful reform happens, the confidence and participation of voters residing outside the country may also be affected, and they too may well be increasingly disinclined to believe that their vote can influence the outcome of an election.

4. Prospects for the enfranchisement of Bangladesh’s absent voters

Unless the current, unsuitable OCV system is reformed and the dichotomy between the normative eligibility of Bangladesh’s absent voters and their de facto disenfranchisement is resolved, prospects for their unimpeded and meaningful inclusion in their country’s elections appear limited.

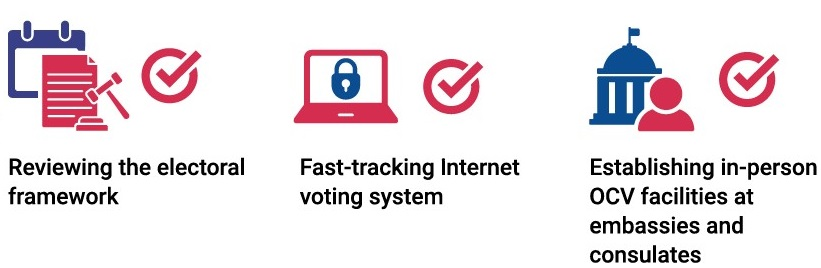

Improving the prospects for the enfranchisement of Bangladesh’s international and internal migrants would entail the following:

- reviewing the electoral framework to extend the legal and operational timelines for in-country elections to accommodate the introduction of OCV;

- simplifying overly complex OCV procedures and timelines for postal voting that are particularly burdensome and highly impractical for most absent voters;

- introducing an intra- or inter-constituency absentee voting system to allow voters to vote from a different constituency from where they are registered;

- complementing a reformed, more accessible and viable absentee postal voting system with in-person OCV facilities at Bangladeshi embassies, consulates and diplomatic missions overseas; and

- conducting OCV awareness campaigns to actively encourage Bangladesh’s absent voters to participate in electoral events in their country and to duly inform them in a timely manner of what is expected for their meaningful participation.

These proposed measures would require amendments to the 1972 Representation of the People Order, as this legislation explicitly mentions postal ballots as the method for OCV. However, the objective of the law is to allow voting by migrants, and postal voting is just the operational means of achieving this objective. Since the main barriers are merely procedural and operational, it is hoped that Bangladesh’s new government will make the necessary legislative amendments to remove them and to adopt the most suitable and inclusive absentee voting system.

Abbreviations

BBS Bangladesh Bureau of Statistics

BEC Bangladesh Election Commission

GCC Gulf Cooperation Council

NID National identity document

OCV Out-of-country voting

References

Abrar, ‘Remittance inflow to Bangladesh accounted for 6.6% of GDP in 2020’, Dhaka Tribune, 18 May 2021, <https://www.dhakatribune.com/business/2021/05/18/remittance-inflow-to-bangladesh-accounted-for-6-6-of-gdp-in-2020>, accessed 4 November 2024

Azad, A., ‘Recruitment of migrant workers in Bangladesh: Elements of human trafficking for labor exploitation’, Journal of Human Trafficking, 5/2 (2019), pp. 130–50, <https://doi.org/10.1080/23322705.2017.1422091>

Bangladesh, People’s Republic of, Bureau of Manpower, Employment and Training (BMET), Ministry of Expatriates’ Welfare and Overseas Employment, [n.d.], <http://www.old.bmet.gov.bd/BMET/stattisticalDataAction>, accessed 12 October 2024

Bangladesh, People’s Republic of, Bureau of Statistics (BBS), Ministry of Planning, ‘Report on Bangladesh Sample Vital Statistics 2018’, May 2019, <https://bbs.portal.gov.bd/sites/default/files/files/bbs.portal.gov.bd/page/6a40a397_6ef7_48a3_80b3_78b8d1223e3f/SVRS_Report_2018_29-05-2019%28Final%29.pdf>, accessed 13 October 2024

Barai, M. K., ‘Development dynamics of remittances in Bangladesh’, SAGE Open, 2/1 (2012), <https://doi.org/10.1177/2158244012439073>

BBC Bengali News, ‘Sansada nirbācana: Yuktarājya prabāsīrā nirbācanē bhōṭa ditē nā pērē hatāśa’ [Parliamentary election: Migrants in United Kingdom frustrated at not being able to vote], 25 December 2018, <https://www.bbc.com/bengali/news-46680515>, accessed 25 October 2024

Chaity, A. J., ‘Only one voter applies for postal ballot’, Dhaka Tribune, 19 December 2018, <https://www.dhakatribune.com/bangladesh/election/2018/12/19/only-one-voter-applies-for-postal-ballot>, accessed 19 November 2024

Dannecker, P., ‘Transnational migration and the transformation of gender relations: The case of Bangladeshi labour migrants’, Current Sociology, 53/4 (2005), pp. 655–74, <https://doi.org/10.1177/0011392105052720>

Ganguly, S., ‘The world should be watching Bangladesh’s election debacle’, Foreign Policy, 7 January 2019, <http://foreignpolicy.com/2019/01/07/the-world-should-be-watching-bangladeshs-election-debacle-sheikh-hasina>, accessed 25 October 2024

Hasan, A. H. R., ‘Internal migration and employment in Bangladesh: An economic evaluation of rickshaw pulling in Dhaka City’, in K. Jayanthakumaran, R. Verma, G. Wan and E. Wilson (eds), Internal Migration, Urbanization and Poverty in Asia: Dynamics and Interrelationships (Singapore: Springer, 2019), <https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-13-1537-4_12>

Human Rights Watch, ‘Bangladesh: Election abuses need independent probe’, 2 January 2019, <https://www.hrw.org/news/2019/01/02/bangladesh-election-abuses-need-independent-probe>, accessed 13 October 2023

International Labour Office, ‘Bangladesh: SWTS Country Brief’, Work4Youth project, December 2016, <https://www.ilo.org/wcmsp5/groups/public/---ed_emp/documents/publication/wcms_537748.pdf>, accessed 25 October 2024

International Organization for Migration (IOM), World Migration Report 2020 (Geneva: IOM, 2020), <https://publications.iom.int/system/files/pdf/wmr_2020.pdf>, accessed 25 October 2024

Khasru, N., ‘Bangladeshi expatriates’ voting rights – and wrongs’, The Daily Star, 30 March 2017, <https://www.thedailystar.net/opinion/society/bangladeshi-expatriates-voting-rights-and-wrongs-1383322>, accessed 13 October 2024

Majumdar, B. A., ‘What kind of parliament we got’, Prothomalo.com, 29 February 2024, <https://en.prothomalo.com/opinion/op-ed/0pars6beyp>, accessed 12 November 2024

Martin, M., Kang, Y., Billah, M., Siddiqui, T., Black, R. and Kniveton, D., ‘Climate-influenced migration in Bangladesh: The need for a policy realignment,’ Development Policy Review, 35/S2 (2017), pp. 357–79, <https://doi.org/10.1111/dpr.12260>

Monem, M., ‘Engagement of Non-resident Bangladeshis (NRBs) in National Development: Strategies, Challenges and Way Forward’, United Nations Development Programme, Final Report, November 2017, <https://info.undp.org/docs/pdc/Documents/BGD/MM%20Final%2002052018%20NRB%20%20report.pdf>, accessed 25 October 2024

Shaikh, E. H., ‘How to cast votes through postal ballot’, Dhaka Tribune, 21 November 2018, <https://www.dhakatribune.com/bangladesh/election/2018/11/21/how-to-cast-votes-through-postal-ballot>, accessed 13 October 2024

Tasneem, S., ‘No country for Bangladeshi women’, The Daily Star, 25 September 2020, <https://www.thedailystar.net/opinion/news/no-country-bangladeshi-women-1966953>, accessed 4 November 2024

United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs (UN DESA), ‘International migrant stock 2020’, <https://www.un.org/development/desa/pd/content/international-migrant-stock>, accessed 13 October 2024

About the author

Ashraful Azad, PhD, is a policy lead at the Settlement Council of Australia in Canberra and an Adjunct Fellow at Western Sydney University. He obtained his PhD at the Faculty of Law and Justice, University of New South Wales, and previously completed a BSS and MSS in International Relations from the University of Chittagong, and an MPhil in International Law from Monash University. He taught at the University of Chittagong and the University of Technology, Sydney, and worked at the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR). Ashraful researched Rohingya displacement, irregular migration in Southeast Asia, politics of migration and settlement in Australia.

About this series

This case study is part of the ‘Absent Voters of South Asia’ project, which falls under the project of ‘Migrations and Elections’ that covers member states of the South Asian Council for Regional Cooperation (SAARC), such as Afghanistan, Bangladesh, Bhutan, India, the Maldives, Nepal, Pakistan and Sri Lanka.

© 2024 International Institute for Democracy and Electoral Assistance

International IDEA publications are independent of specific national or political interests. Views expressed in this publication do not necessarily represent the views of International IDEA, its Board or its Council members.

With the exception of any third-party images and photos, the electronic version of this publication is available under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 (CC BY-NC-SA 4.0) licence. You are free to copy, distribute and transmit the publication as well as to remix and adapt it, provided it is only for non-commercial purposes, that you appropriately attribute the publication, and that you distribute it under an identical licence. For more information visit the Creative Commons website: <http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/4.0>.

Design and layout: International IDEA

DOI: <https://doi.org/10.31752/idea.2025.99>

ISBN: 978-91-7671-852-0 (PDF)

ISBN: 978-91-7671-919-0 (HTML)