The Absent Voters of Afghanistan

Challenges and Prospects for the Enfranchisement of Migrants

Introduction

This case study examines the challenges and prospects for enfranchising migrants and displaced populations in any future elections should democracy one day be restored in Afghanistan. Drawing on historical context and legal frameworks, the case study identifies the reasons behind the exclusion of displaced populations and how their electoral rights, guaranteed by the 2004 Constitution, have been largely unrealized. Despite legal protections, various challenges hindered participation in past elections in Afghanistan, including financial constraints, security concerns and logistical limitations. While a limited—and highly costly—out-of-country voting initiative was conducted for the 2004 presidential election, subsequent attempts were unsuccessful.

Following the Taliban’s takeover1 in August 2021, elections are no longer held, and the future of political rights for Afghanistan’s voters remains uncertain. Despite the current circumstances, the study emphasizes the importance of respecting and fulfilling these rights in any future democratic regime. Examining the prospects for enfranchisement in the wake of the Taliban’s takeover, the study outlines several recommendations for a future return to a democratic system, emphasizing the need to guarantee and respect the political and electoral rights of all Afghans, including migrants and displaced populations.

1. History and context of displacement in Afghanistan

Afghanistan has long been a country with a highly unsettled population. Three out of every four citizens have experienced displacement at some point in their lifetime (ICRC 2009).

The overwhelming majority of Afghanistan’s displaced citizens are either refugees who fled beyond the country’s borders, internally displaced persons (IDPs) or economic migrants (UNHCR 2024).

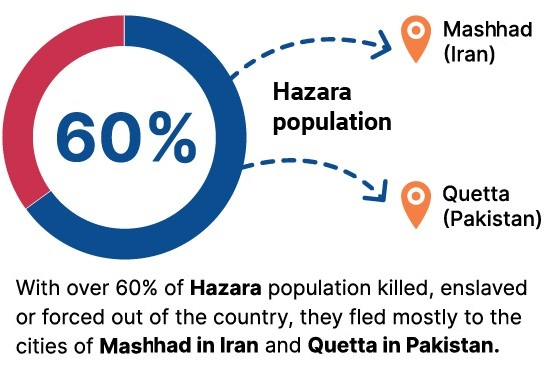

The literature on the displacement of Afghans often begins with the Soviet Union’s invasion in 1979. However, the first wave of forced migration in modern Afghanistan began in the reign of Abdul Rahman Khan (1880–1901), the first Afghan Emir to declare jihad against the people of his own kingdom. In particular, Khan targeted the Hazaras, who were followers of a different form of the Islamic faith, having first violently attacked the Pashtun Ghilzai tribes (Barfield 2010: 149–50). His brutal war against the Hazaras led to over 60 per cent of the Hazara population being killed, enslaved or forced out of the country. The displaced population fled mostly to the cities of Mashhad in Iran, and Quetta in Pakistan (Barfield 2010: 150).

Following the reign of Abdul Rahman Khan, it remained official policy to forcibly relocate populations, uprooting any tribe (mostly Pashtun) considered potentially hostile and depopulating fertile regions occupied by ethno-religious minorities and to gift these to allies (Law Library of Congress 2004).

Afghanistan has been in conflict since the Soviet Union invaded in 1979. Its people have fled to neighbouring countries in large numbers, while natural disasters—such as earthquakes, landslides and floods—have been a further major push factor for internal displacement.

In addition to a large number of displaced citizens, Afghanistan has a population of nomads, the Kuchis. As a traditional nomadic or semi-nomadic group, the Kuchis are primarily of Pashtun origin, although some are from other ethnic groups, such as the Baloch and Tajiks. Their precise numbers are difficult to determine due to challenges in accurately counting nomadic and semi-nomadic groups, but estimates place the Kuchis at around 1.5 million to 2 million in a population of approximately 32.9 million (NSIA 2021).

The mobility of the purely nomadic Kuchi population is primarily determined by a combination of the weather and trading opportunities; the movements of the semi-nomadic are determined by their own decisions (Minority Rights Group n.d.). The Kuchis have suffered greatly from the past decades of war, and their livelihoods and way of life are under threat.

New waves of mass displacement in Afghanistan began in 1978 under the Soviet Union–backed communist government of President Mohammad Daud Khan. A series of invasions and regime changes caused fresh waves of internal and external displacement. The Soviet Union’s occupation from 1979 to 1988 prompted an exodus of approximately 4.6 million Afghans. The Mujahidin victory and Taliban rule in 1992–2001 led an estimated 300,000 to seek refugee status in Pakistan alone. During the period of US-led occupation (2001–2021), there were an average of 65,000 relocations per year. These movements were officially recorded from 2005 (Willner-Reid 2017). The fall of Kabul to the Taliban on 15 August 2021 led to a mass evacuation and exodus of 130,000 Afghans within 15 days (Bouchard 2021).

Around 2.6 million Afghans took refuge in Iran in 1979–1980, and another 1.5 million fled to Pakistan. While most refugees in Iran received some form of documentation and settled in various cities, refugees in Pakistan remained in camps and received no documentation (UNDP 2021). Despite the repatriation of groups of Afghans from different countries in 1978–2021, Afghanistan still generates among the highest numbers of refugees worldwide (Jackson 2009). As noted above, the International Committee of the Red Cross (2009) reported that more than three-quarters of all Afghans (76 per cent) had experienced some form of displacement in their lifetime, and that 42 per cent of this number had been externally displaced (Lopez-Lucia 2015).

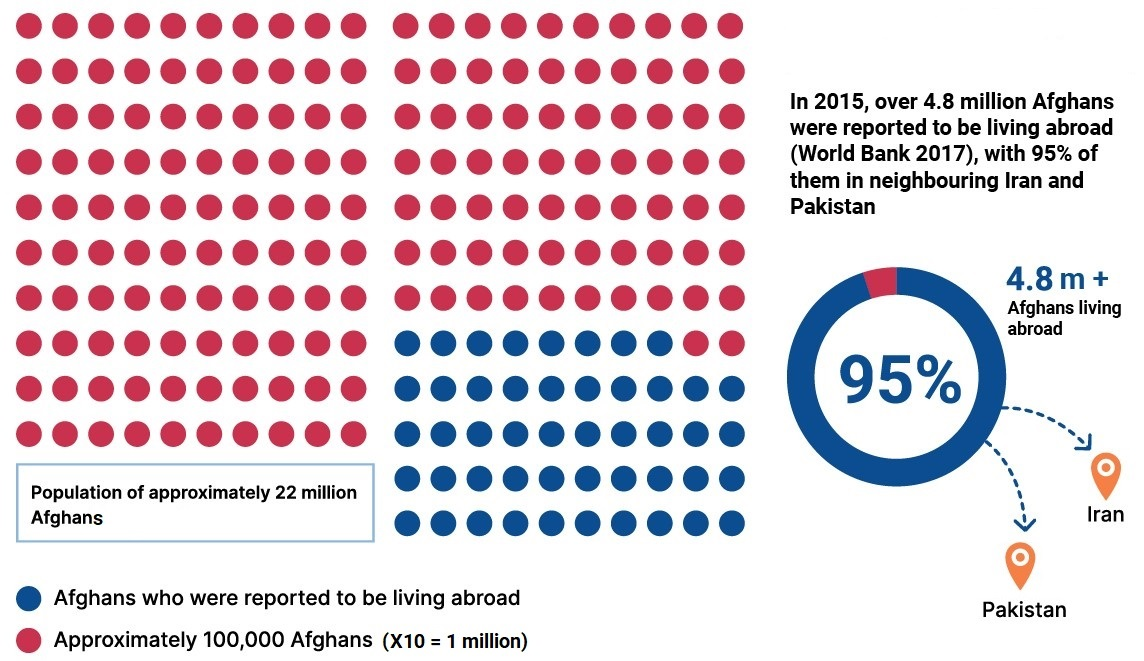

By 2015 over 4.8 million Afghans were reported to be living abroad, 95 per cent of them in neighbouring Iran and Pakistan (Garrote-Sanchez 2017). Other regions and countries with high numbers of Afghan migrants were the Gulf states (360,000), Germany (100,000), the United States (89,000), the United Kingdom (60,000), Tajikistan (57,000), Canada (48,000) and the Netherlands (33,000).

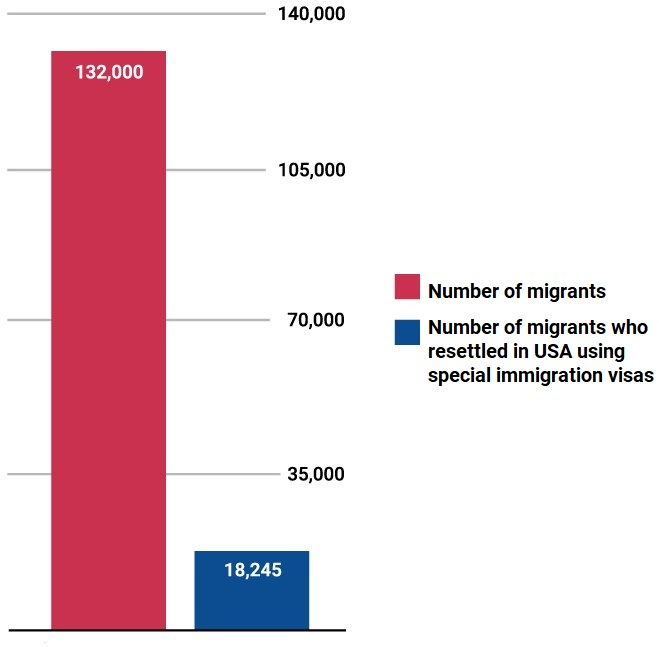

Since 2015 the number of international migrants has increased still further. For example, the number of Afghan migrants in the USA increased to 132,000 (Montalvo and Batalova 2024). A further 18,245 migrants resettled in the USA using special immigration visas in 2020 and 2021 (Waddell 2021).

These numbers probably do not accurately reflect the actual extent of international migration, as they do not account for the irregular, undocumented migration that has taken place on a larger scale than regular, documented movements. According to several sources, only 14 per cent of those who migrated externally in 2011 travelled with legal documents (IOM 2014). For example, in 2022 the number of Afghan migrants in the USA had increased to 195,000 (Batalova 2024); around 3 million were undocumented migrants, a significant difference from the 85,000 migrants reported in most official reports (Garrote-Sanchez 2017). In 2011 it was estimated that over 45,000 undocumented Afghans were living in Europe (IOM 2014).

The continuing escalation of violence across Afghanistan coupled with poverty and natural disasters have increased the number of IDPs substantially.

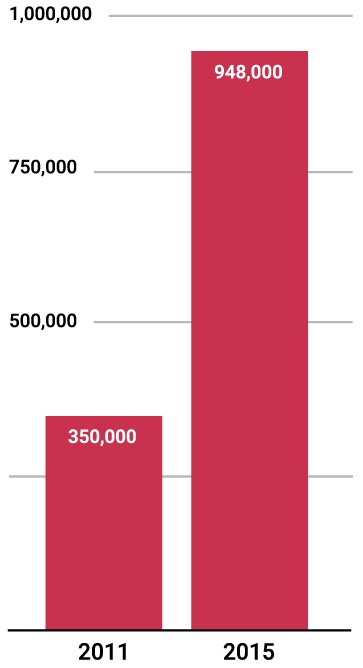

There were around 350,000 IDPs in 2011 (UNHCR n.d.; Brookings Institution 2010), a number that almost tripled to 948,000 in 2015 (Glatz 2015; Lopez-Lucia 2015). After 2001 most IDPs moved to camps in government-controlled areas of Afghanistan for their own protection and to be able to receive international aid. As the government-controlled regions started to shrink, however, IDPs began to relocate, but gradually they all fell into the hands of the Taliban (Solomon and Stark 2011). By 2021 many had exhausted all their resources, lost access to international assistance (Amnesty International 2021) and were awaiting retribution from the Taliban.

When Kabul fell to the Taliban in August 2021, thousands of Afghans rushed to the airport, trying to escape a further cycle of violence, human rights violations and political repression. Approximately 130,000 people were airlifted out of Afghanistan by the end of August 2021, and around 200 people died while attempting to leave (Reuters 2021). Many Afghans were left stranded at the border with Pakistan, Iran or the Central Asian countries. Many more were turned away from airports and borders to await an uncertain fate (Fox and Knickmeyer 2021).

Previous studies have estimated a net outflow of 85,000 economic migrants each year (Garrote-Sanchez 2017). Over 53 per cent of households already had at least one member who was an economic migrant in 2014 (IOM 2014). Economic migrants are overwhelmingly single males. Data from the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR n.d.), for example, shows that 80–85 per cent of labour migrants who crossed the border into Pakistan in 2011 were single males.

2. Drivers of displacement within and outside Afghanistan

War, violent conflict and human rights abuses

Several studies identify war and violent conflict, poverty and food insecurity, human-induced and natural disasters, and human trafficking as the main push factors for Afghanistan’s large-scale internal and external population displacement (Solomon and Stark 2011: 264; Garrote-Sanchez 2017: 1). These factors have made substantial numbers of families homeless. Violent conflict has been the leading cause of displacement, followed by food insecurity (Brookings Institution 2010). The United Nations Development Programme (2021) forecast in 2021 that poverty would replace conflict as the leading cause of migration or displacement, arguing that over 97 per cent of the Afghan population could be plunged into poverty by mid-2022.

Earthquakes, landslides, droughts and seasonal flooding have also destroyed lives and livelihoods and routinely displace affected populations within Afghanistan. The country is hit by an earthquake with a magnitude of 5 or 6 on the Richter scale at least twice a year (UNDP 2021: 50).

Human trafficking is a major factor in displacement, particularly of minors. Girls are usually targeted for prostitution and sometimes for forced labour, while boys are targeted for forced labour or recruited as fighters by insurgent groups in neighbouring countries. Many minors are smuggled with the consent of families who lack sufficient funds to pay for the entire family to migrate (OHCHR 2022).

3. Electoral rights of Afghanistan’s displaced citizens

Following the Taliban’s ouster in 2001, Afghanistan finally had an opportunity to put an end to decades of conflict and establish a democratic system of governance and a functioning state. In 2004, a Loya Jirga—a traditional gathering, or ‘grand council’, of representatives from the various tribes and factions within the country—was summoned to deliberate on and adopt a new constitution. Afghan experts returned from exile to engage in the process of drafting the new constitution, which was then adopted in 2004. Elections were organized at all levels of governance—the presidency, the legislature and provincial councils (Rubin 2004). This positive transformation increased confidence in a better future among Afghans and led 6.4 million citizens to return to the country (Garrote-Sanchez 2017).

The 2004 Constitution of Afghanistan prohibits the exclusion of displaced persons from the electoral process, be they inside or outside the country. This prohibition is reiterated in several national laws, as well as international treaties and conventions ratified by Afghanistan. The 2004 Constitution, abrogated by the Taliban following their return to power in 2021, guaranteed equal political rights to all citizens—both men and women—entitling them to vote and be nominated as candidates. Article 33(1) stated that ‘citizens of Afghanistan have the right to elect and be elected’. Subsequent election laws elaborated on and affirmed these core constitutional principles, and specifically required that the state provide the conditions for internally and externally displaced persons to participate in national elections and have meaningful representation in the resulting institutions of governance.

The Constitution reserved an average of at least two seats in the lower house per province for women. In addition, the election law allocated 10 seats in the lower house for Kuchis and one seat each for the Hindu and Sikh communities. In the Senate, to which the president was constitutionally empowered to appoint one-third of the members, there was a requirement to appoint women, persons with disabilities, ethnic minorities or young people to at least 16 seats.

At the time, citizens displaced either inside or outside the country comprised approximately one-third of the entire population. After the enactment of the 2004 Constitution, however, a strategic opportunity to expand both the inclusion and the protection of Afghanistan’s displaced voters was missed. This could have been the moment to address the representation of internally and externally displaced persons through, for example, reserved seats or a mechanism for the special representation of absent voters.

The UN and other international organizations repeatedly recommended the inclusion of displaced citizens in Afghan elections (OSCE/ODIHR 2009). This pressure led to an explicit acknowledgment of their exclusion in the 2010 Election Law (article 5), which sought to address the problem by mandating that the Independent Election Commission (IEC) of Afghanistan take the necessary steps to facilitate the participation of refugees, IDPs, nomads and persons with disabilities in elections at all levels of government. The Election Law specifically prohibited the exclusion of citizens from the electoral franchise based on their social status, which included IDPs (Brookings Institution 2010: 27). The Electoral Law (article 14) also mandated that the state and the IEC establish special mechanisms to enable absentee voting to facilitate the participation of IDPs.

4. Electoral rights of Afghanistan’s displaced citizens: Reflections on practice

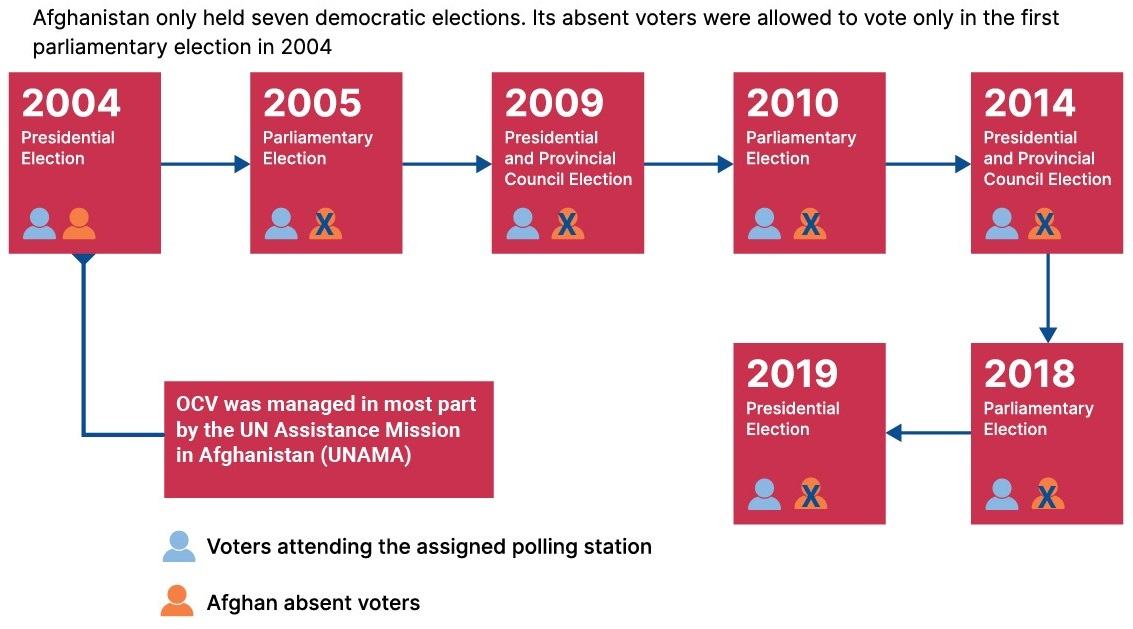

Despite the existence of legal protections for the political rights of Afghan migrants and displaced citizens, being absent or even forced out of their places of residence or the country made it almost impossible for them to participate in elections. In the period 2004–2019, Afghanistan held seven national elections—a presidential election in 2004, a parliamentary election in 2005, presidential and provincial council elections in 2009, a parliamentary election in 2010, presidential and provincial council elections in 2014, a parliamentary election in 2018 and a presidential election in 2019.

The only election in which migrants and displaced citizens were able to vote was the first—the presidential election in 2004. This election was managed for the most part by the UN Assistance Mission in Afghanistan, which made considerable efforts to enfranchise Afghanistan’s absent voters and enable them to participate in the election (UNAMA 2003). On that occasion, only refugees in Pakistan and Iran were able to register as voters. Since almost 95 per cent of the diaspora was hosted by these two countries, this was a significant development (NDI 2011). In fact, their participation in the election constituted the largest OCV programme in the world (SIGAR 2021). OCV in these two countries was administered by the International Organization for Migration (Constable 2004; NDI 2011).

In subsequent elections, the government and the IEC gave several reasons why international migrants and refugees could not be enfranchised.

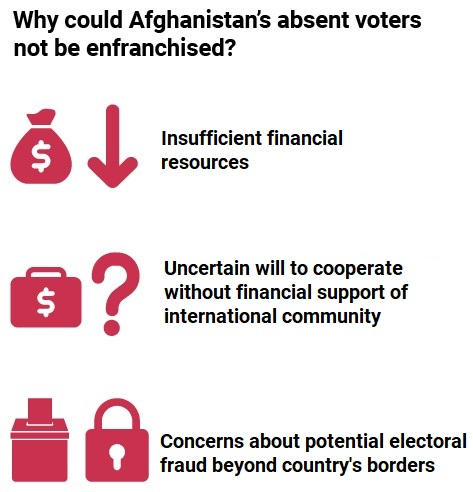

First, they stated that, in almost all elections, financial resources were insufficient to allow the participation of eligible voters from outside the country (Sayed and Hakim 2018). The IEC estimated that OCV operations in Iran and Pakistan alone would have cost USD 50 million, which the government was unable to finance, and the international community was unwilling to contribute (Haider 2009). Almost all the costs of Afghan elections for in-country voters were borne by the international community.

Second, although both Iran and Pakistan repeatedly declared their readiness to assist Afghanistan in holding elections for migrants and refugees inside their countries, the Afghan Government was uncertain that they would be willing to cooperate without the financial support of the international community (IRIN News 2005; Sayed and Hakim 2018).

Finally, some in the government feared instances of potential electoral fraud beyond Afghanistan’s borders, possibly under the influence of neighbouring countries (Bekaj and Antara 2018).

Although the 2004 Election Law did not reserve a specific number of seats for migrants’ representatives, a few migrants2 stood in presidential and parliamentary elections, with many returning to Afghanistan to stand for parliamentary seats in various provinces.3 The use of the single non-transferable vote (SNTV) system for parliamentary elections significantly increased the chances that these candidates could be successful, as this system did not require that a candidate win a majority or even a plurality of votes in a particular electoral district. Under the SNTV system, some candidates managed to obtain seats with only around 1 per cent of the votes in their districts due to the high number of seats being contested and the even higher number of candidates competing for them (Johnson 2018). This ultra-low threshold for winning a seat increased the role of wealth and political patronage in determining electoral outcomes. For several migrants, their wealth increased their chances of winning.

Unlike Afghanistan’s international migrants and refugees located outside the country, a greater number of IDPs were able to participate in elections, but not without having to overcome many challenges. For example, public awareness campaigns, election campaigns, announcements and documents were mostly available in the Dari and Pashtu languages, leaving minorities and displaced populations who spoke different local languages less informed about the process (OSCE/ODIHR 2009). In addition, many among the displaced population no longer possessed their national identity card (Tazkira)—mainly for reasons associated with their displacement—an identification document needed to obtain a voting card and hence to be able to vote. Most were also unable to obtain new Tazkiras because the Law on Registration of Population Records required that they apply at their province of origin, a place to which they could no longer return.4

The participation of IDPs in Afghan elections has historically encountered significant problems and an inconsistent application of voter eligibility. Voter registration was not conducted in all IDP camps, often due to the fact that residents did not possess government-issued identification documents necessary for voting eligibility. While non-registered IDPs are typically ignored by the election campaigns, often wealthy candidates targeted registered IDP residents in camps, offering them temporary financial incentives in exchange for their support, rather than addressing their long-term needs. Instances in which residents of IDP camps were issued multiple voter cards were also reported. Before the 2009 presidential elections, for example, the IEC issued almost 5 million voting cards, allegedly for newly eligible voters and recent returnees among the displaced population (OSCE/ODIHR 2009). However, 5 million new voting cards put the total number of voting cards at 17.5 million, which exceeded the entire electorate, estimated at around 15 million (OSCE/ODIHR 2009). Another 3 million voting cards were issued for the 2014 presidential election, giving a total of over 20 million voting cards (Männik 2014). The Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe reported that irregularities behind the issuance of voter cards led to a scale of fraud that was beyond any correctional retallying measures (OSCE/ODIHR 2009: 33).

5. Prospects for the enfranchisement of displaced Afghan voters

Immediately after assuming power, the Taliban declared that elections would no longer take place in Afghanistan (Al Jazeera 2001). It is therefore unlikely that any citizens—inside or outside the country—will be able to exercise their right to vote for the foreseeable future. Furthermore, as the perpetrators of forced displacement and violence targeting ethnic and religious minorities in Afghanistan, particularly the Hazara Shia community (Akbari 2022), the Taliban can hardly be expected to respect or protect the civil and political rights of Afghanistan’s displaced populations.

If Afghanistan’s history offers one lesson, however, it is that an unpopular government is unlikely to be able to sustain itself in the long term. Given the country’s difficult history of conflict, and of ethnic and tribal division, as well as its geography, which is conducive to guerrilla warfare, any government that seeks to endure in the long term must gain popular trust and acceptance. For all its flaws, Afghanistan’s brief transition to democracy produced a short interregnum during which its people experienced many freedoms and enjoyed many rights. As a result, they might yet dare to dream of bringing democracy back to their country one day in the future.

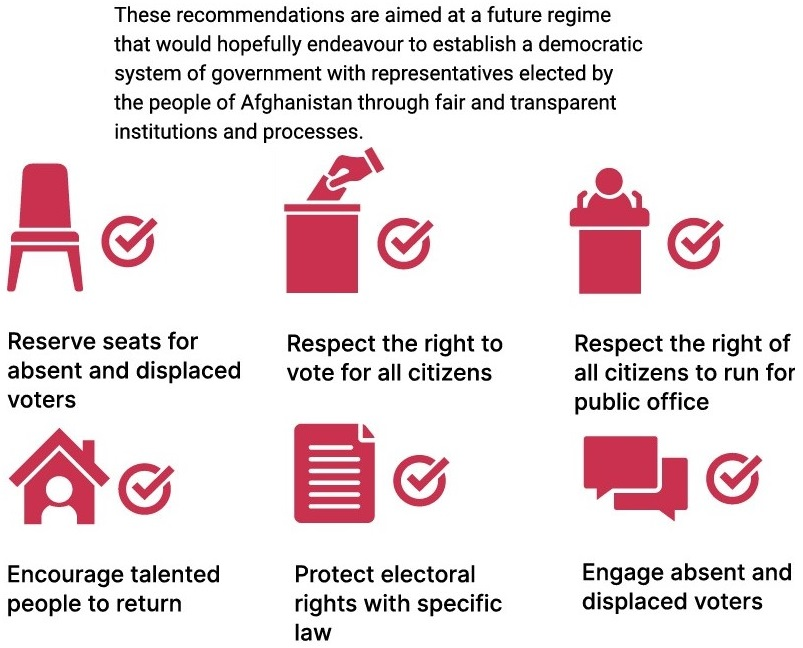

The following recommendations are aimed at a future form of government that would hopefully endeavour to establish a democratic system made by representatives elected directly by the people of Afghanistan through an independent electoral management body and inclusive, credible and transparent electoral processes.

Such a government should consider the following:

- respect the right to vote for all citizens, irrespective of gender, origin, religion, social class, status or whereabouts, including Afghanistan’s international and internal migrants and displaced populations;

- respect the right of all citizens, including international and internal migrants, to run for public office;

- reserve seats for absent and displaced voters: enfranchising these excluded absent citizens would be particularly important in the case of Afghanistan, where one-third of its population is currently displaced; and

- protect the electoral rights of absent and displaced voters by adopting a specific law to enable and facilitate all aspects of their electoral enfranchisement.

While enshrining in legislation the electoral rights of migrant and displaced populations would be a positive step, it alone will not be sufficient to guarantee their participation in elections or their political representation. Any future democratic government in Afghanistan should ensure that migrants and displaced populations are able to vote and that they can stand as candidates, thus meaningfully compete for seats.

Various practical measures would contribute to these overall goals:

- making sufficient budgetary provisions and logistical arrangements to support the participation of millions of migrants and displaced citizens;

- creating a dedicated department at the IEC responsible for formulating policies and adopting related measures to ensure the enfranchisement of displaced voters, both inside Afghanistan and abroad;

- encouraging host countries to assist with funding and organizing OCV operations in their jurisdictions, providing documents for irregular migrants and registering eligible Afghan citizens residing in their territories to vote; and

- reaching out to the diaspora and engaging them in the electoral process as both voters and candidates.

Abbreviations

IDP Internally displaced person

IEC Independent Election Commission

OCV Out-of-country voting

SNTV Single non-transferable vote

References

Akbari, F., ‘The Risks Facing Hazaras in Taliban-ruled Afghanistan’, Program on Extremism at George Washington University, 7 March 2022, <https://extremism.gwu.edu/risks-facing-hazaras-in-taliban-ruled-afghanistan>, accessed 31 October 2024

Al Jazeera, ‘‘‘No need’’: Taliban dissolves Afghanistan election commission’, 25 December 2021, <https://www.aljazeera.com/news/2021/12/25/taliban-dissolves-afghanistan-election-commission>, accessed 31 October 2024

Amnesty International, ‘Afghanistan: Country’s four million internally displaced need urgent support amid pandemic’, 30 March 2021, <https://www.amnesty.org/en/latest/news/2021/03/afghanistan-countrys-four-million-internally-displaced-need-urgent-support-amid-pandemic-2/>, accessed 31 October 2024

Barfield, T., Afghanistan: A Cultural and Political History (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2010), <https://doi.org/10.23943/princeton/9780691145686.001.0001>

Bekaj, A. and Antara, L., Political Participation of Refugees: Bridging the Gaps (Stockholm: International IDEA, 2018), <https://doi.org/10.31752/idea.2018.19>

Bouchard, K., ‘Afghan evacuees begin to arrive in Maine’, Portland Press Herald, 15 October 2021, <https://www.pressherald.com/2021/10/15/afghan-evacuees-begin-to-arrive-in-maine/>, accessed 30 October 2024

Brookings Institution, ‘Realizing National Responsibility for the Protection of Internally Displaced Persons in Afghanistan: A Review of Relevant Laws, Policies, and Practices’, 30 November 2010, <https://www.brookings.edu/research/realizing-national-responsibility-for-the-protection-of-internally-displaced-persons-in-afghanistan-a-review-of-relevant-laws-policies-and-practices/>, accessed 25 October 2024

Constable, P., ‘Bringing the vote to Afghan refugees’, The Washington Post, 30 August 2004, <https://www.washingtonpost.com/archive/politics/2004/08/30/bringing-the-vote-to-afghan-refugees/2776f21a-3085-4067-9711-46e5e8e7efc7/>, accessed 25 October 2024

DW, ‘Afghan election sees just one in five voters cast ballot’, 29 September 2019, <https://www.dw.com/en/afghan-election-sees-just-one-in-five-voters-cast-ballot/a-50629649>, accessed 31 October 2024

European Union Agency for Asylum (EUAA), Iran – Situation of Afghan Refugees (Luxembourg: Publications Office of the European Union, 2022), <https://euaa.europa.eu/sites/default/files/publications/2023-01/2023_01_COI_Report_Iran_Afghans_Refugees_EN.pdf>, accessed 31 October 2024

Fox, B. and Knickmeyer, E., ‘US expects to admit more than 50,000 evacuated Afghans’, Associated Press, 4 September 2021, <https://apnews.com/article/migration-1a704e14f08d0bdf872d84b8e96fd2bf>, accessed 25 October 2024

Garrote-Sanchez, D., International Labor Mobility of Nationals: Experience and Evidence for Afghanistan at Macro Level (Washington, DC: World Bank, 2017), <https://doi.org/10.1596/30268>

Glatz, A. K., ‘Afghanistan: New and long-term IDPs risk becoming neglected as conflict intensifies’, Norwegian Refugee Council, 16 July 2015, <https://reliefweb.int/report/afghanistan/afghanistan-new-and-long-term-idps-risk-becoming-neglected-conflict-intensifies>, accessed 25 October 2024

Haider, Z., ‘Afghan refugees in Pakistan yearn to vote’, Reuters, 18 August 2009, <https://www.reuters.com/article/us-afghanistan-election-refugees/afghan-refugees-in-pakistan-yearn-to-vote-idUSTRE57H1XE20090818>, accessed 25 October 2024

International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC), ‘Our World: Views from Afghanistan’, Opinion Survey, June 2009, <https://www.icrc.org/en/doc/assets/files/other/our-world-views-from-afghanistan-i-icrc.pdf>, accessed 25 October 2024

International Organization for Migration (IOM), Afghanistan: Migration Profile (Kabul: IOM, 2014), <https://afghanistan.iom.int/sites/g/files/tmzbdl1071/files/documents/afghanistan_migration_profile.pdf>, accessed 25 October 2024

—, World Migration Report 2024, <

International Rescue Committee (IRC), ‘Internal displacement in Afghanistan has soared by 73% since June’, press release, 23 August 2021, <https://www.rescue.org/press-release/irc-internal-displacement-afghanistan-has-soared-73-june>, accessed 31 October 2024

IRIN News, ‘Pakistan: No provision for Afghan refugees to vote’, The New Humanitarian, 1 September 2005, <https://www.thenewhumanitarian.org/news/2005/09/01/no-provision-afghan-refugees-vote>, accessed 25 October 2024

Jackson, A., The Cost of War: Afghan Experiences of Conflict, 1978–2009 (London: Oxfam, 2009)

Johnson, T. H., ‘The illusion of Afghanistan’s electoral representative democracy: The cases of Afghan presidential and national legislative elections’, Small Wars & Insurgencies, 29/1 (2018), pp. 1–37, <https://doi.org/10.1080/09592318.2018.1404771>

Law Library of Congress, ‘Afghanistan Country Study 2004’, LL File No. 2004-00209, LRA-D-PUB-000276, Global Legal Research Directorate, August 2004, <https://tile.loc.gov/storage-services/service/ll/llglrd/2019669455/2019669455.pdf>, accessed 31 October 2024

Lopez-Lucia, E., ‘Migration and conflict in Afghanistan’, GSDRC Helpdesk Research Report 1243/2015, July 2015, <https://gsdrc.org/publications/migration-and-conflict-in-afghanistan/>, accessed 25 October 2024

Männik, E., ‘Afghanistan on the eve of elections: 10 million voters, 20 million voter cards’, International Centre for Defence and Security, 17 March 2014, <https://icds.ee/en/afghanistan-on-the-eve-of-elections-10-million-voters-20-million-voter-cards/>, accessed 25 October 2024

Minority Rights Group, ‘Kuchis in Afghanistan’, [n.d.], <https://minorityrights.org/minorities/kuchis/>, accessed 25 October 2024

Montalvo, J. and Batalova, J., ‘Afghan immigrants in the United States’, Migration Policy Institute, 15 February 2024, <https://www.migrationpolicy.org/article/afghan-immigrants-united-states>, accessed 7 November 2024

National Democratic Institute (NDI), ‘The 2010 Wolesi Jirga Elections in Afghanistan’, 2011, <https://aceproject.org/ero-en/regions/asia/AF/afghanistan-final-report-legislative-elections-ndi>, accessed 25 October 2024

National Statistics and Information Authority (NSIA), ‘Afghanistan Statistical Yearbook 2020’, Issue No: 42, Second Version, August 2021, <http://nsia.gov.af:8080/wp-content/uploads/2021/04/Statistical-Year-book-2020.pdf>, accessed 31 October 2024

Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights (OHCHR), ‘Trafficking in persons in conflict situations: The world must strengthen prevention and accountability’, statement on International World Day Against Trafficking in Persons, 29 July 2022, <https://www.ohchr.org/en/statements/2022/07/trafficking-persons-conflict-situations-world-must-strengthen-prevention-and>, accessed 31 October 2024

Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe, Office for Democratic Institutions and Human Rights (OSCE/ODIHR), ‘Islamic Republic of Afghanistan: Presidential and Provincial Council Elections—20 August 2009’, Final Report, 8 December 2009, <https://www.osce.org/files/f/documents/8/5/40753.pdf>, accessed 25 October 2024

Reuters, ‘Evacuations from Afghanistan by country’, 30 August 2021, <https://www.reuters.com/world/evacuations-afghanistan-by-country-2021-08-26/>, accessed 25 October 2024

Rubin, B. R., ‘Crafting a Constitution for Afghanistan’, Journal of Democracy, 15/3 (2004), pp. 5–19, <https://journalofdemocracy.org/articles/crafting-a-constitution-for-afghanistan/>, accessed 31 October 2024

Sayed, R. and Hakim, A. K., ‘Afghan refugees face political alienation’, DW, 11 October 2018, <https://www.dw.com/en/without-voting-rights-afghan-refugees-face-political-alienation/a-45848084>, accessed 25 October 2024

Solomon, A. and Stark, C., ‘Internal displacement in Afghanistan: Complex challenges to government response’, in E. Ferris, E. Mooney and C. Stark (eds), From Responsibility to Response: Assessing National Approaches to Internal Displacement (The Brookings Institution – London School of Economics Project on Internal Displacement, 2011), <https://www.brookings.edu/wp-content/uploads/2016/06/From-Responsibility-to-Response-Nov-2011_Afghanistan.pdf>, accessed 25 October 2024

Special Inspector General for Afghanistan Reconstruction (SIGAR), ‘Elections: Lessons from the U.S. experience in Afghanistan’, Interactive Summary, February 2021, <https://www.sigar.mil/interactive-reports/elections/index.html>, accessed 25 October 2024

United Nations Assistance Mission in Afghanistan (UNAMA), ‘2004 Afghanistan presidential election: Operational plan outline’, 31 July 2003, <https://aceproject.org/ero-en/regions/asia/AF/presidential-election-ops-plan.pdf>, accessed 25 October 2024

United Nations Development Programme (UNDP), ‘97 percent of Afghans could plunge into poverty by mid 2022, says UNDP’, 9 September 2021, <https://www.undp.org/press-releases/97-percent-afghans-could-plunge-poverty-mid-2022-says-undp>, accessed 25 October 2024

United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR), ‘UNHCR Global Report 2011 – Afghanistan’, [n.d.], <https://www.unhcr.org/media/unhcr-global-report-2011-afghanistan>, accessed 25 October 2024

—, ‘Afghanistan situation’, Global Appeal 2024, <https://reporting.unhcr.org/afghanistan-situation-global-appeal-2024>, accessed 31 October 2024

Waddell, B., ‘States that have welcomed the most refugees from Afghanistan’, U.S. News, 14 September 2021, <https://www.usnews.com/news/best-states/articles/2021-09-14/afghan-refugee-resettlement-by-state>, accessed 25 October 2024

Willner-Reid, M., ‘Afghanistan: Displacement Challenges in a Country on the Move’, Migration Policy Institute, Profile, 16 November 2017, <https://www.migrationpolicy.org/article/afghanistan-displacement-challenges-country-move>, accessed 31 October 2024

About this series

This case study is part of the ‘Absent Voters of South Asia’ project, which falls under the project of ‘Migrations and Elections’ that covers member states of the South Asian Council for Regional Cooperation (SAARC), such as Afghanistan, Bangladesh, Bhutan, India, the Maldives, Nepal, Pakistan and Sri Lanka.

© 2024 International Institute for Democracy and Electoral Assistance

International IDEA publications are independent of specific national or political interests. Views expressed in this publication do not necessarily represent the views of International IDEA, its Board or its Council members.

With the exception of any third-party images and photos, the electronic version of this publication is available under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 (CC BY-NC-SA 4.0) licence. You are free to copy, distribute and transmit the publication as well as to remix and adapt it, provided it is only for non-commercial purposes, that you appropriately attribute the publication, and that you distribute it under an identical licence. For more information visit the Creative Commons website: <http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/4.0>.

Design and layout: International IDEA

DOI: <https://doi.org/10.31752/idea.2024.98>

ISBN: 978-91-7671-851-3 (PDF)

ISBN: 978-91-7671-918-3 (HTML)