Q&A: Sanaa Alsarghali on the future of Palestinian internal governance

With the collapse of the ceasefire in Gaza and ongoing Israeli military operations in West Bank cities such as Jenin and Tulkarem, attention, albeit cautiously, is once again turning toward the internal dynamics of Palestinian politics.

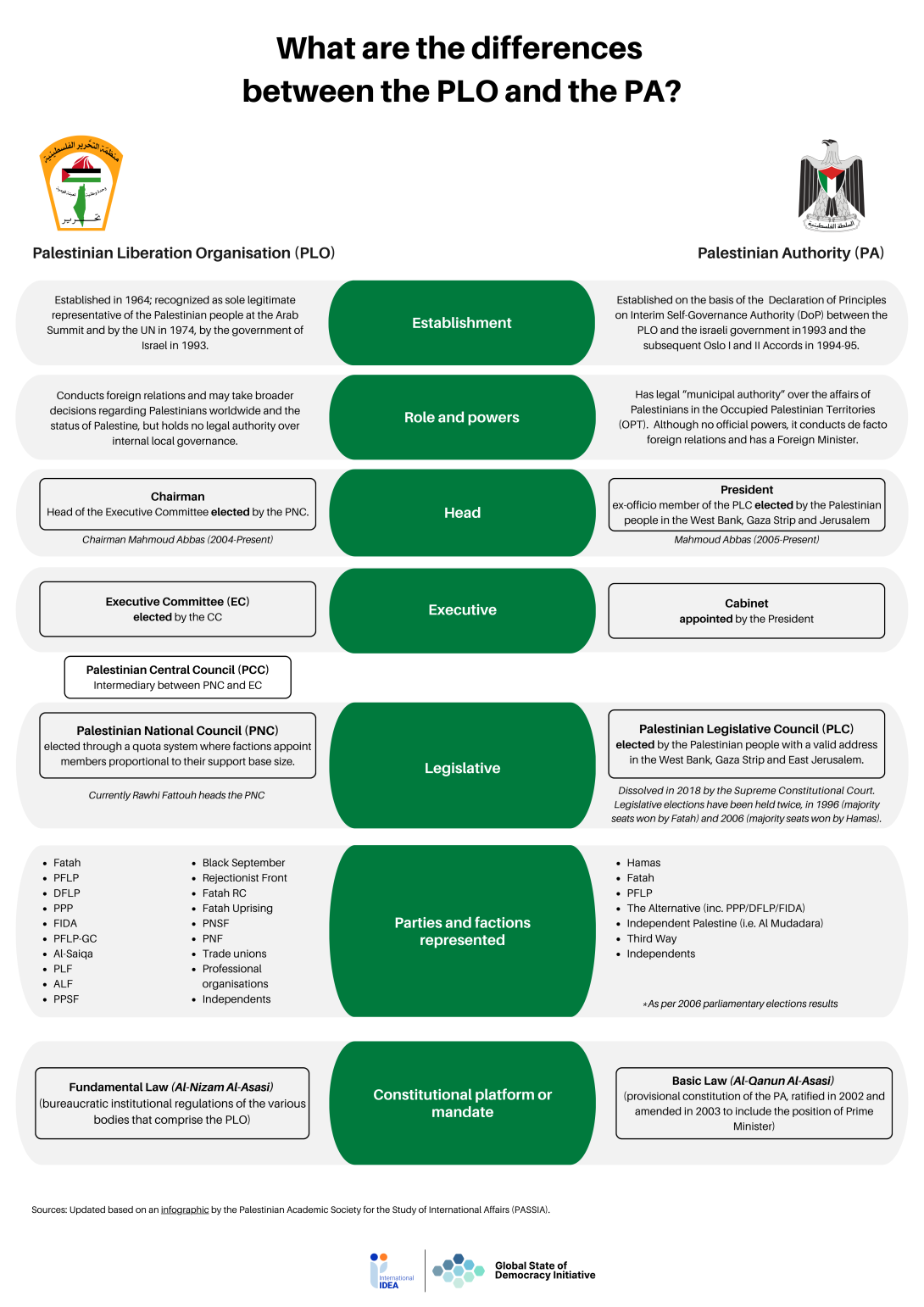

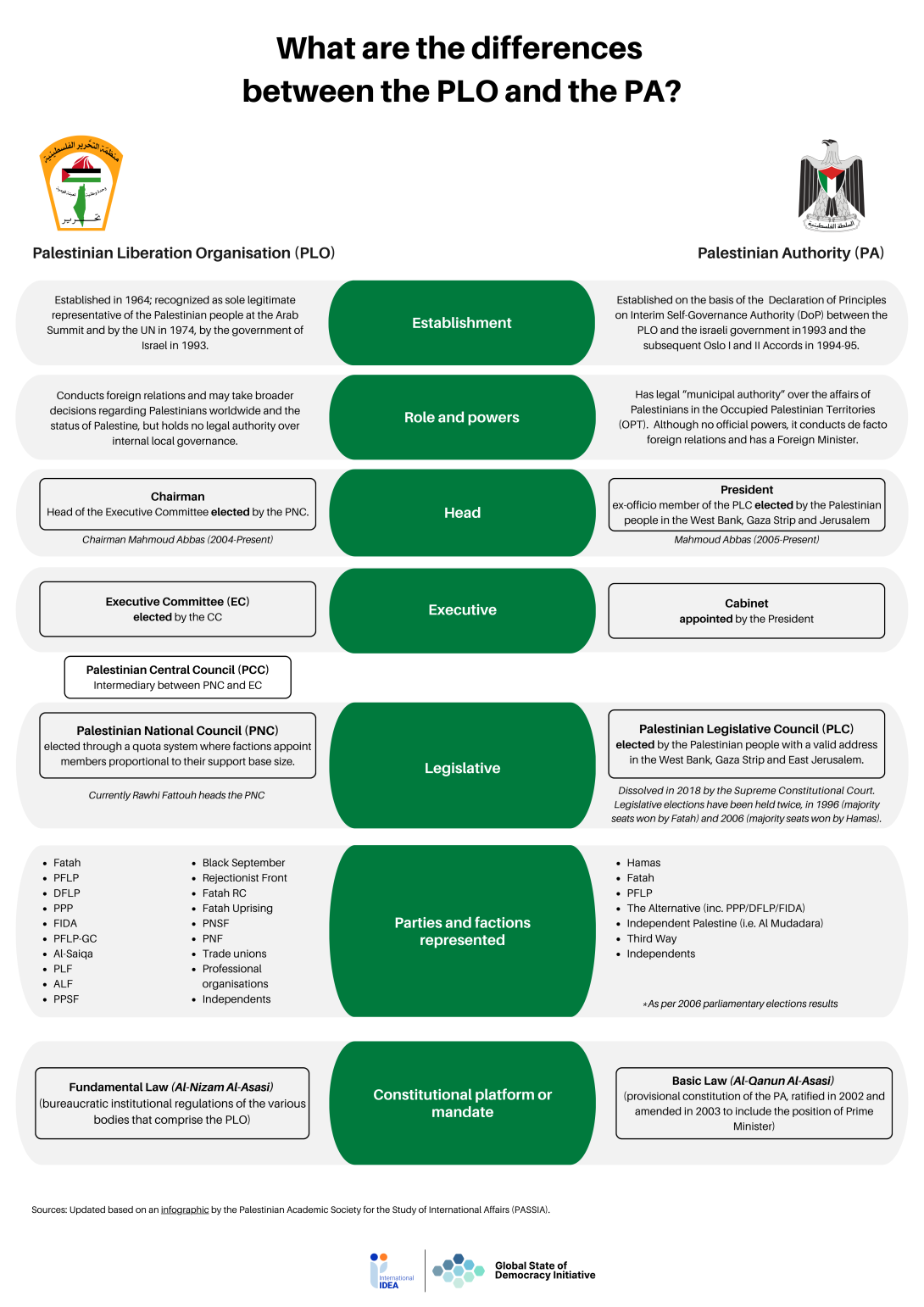

Recent developments, including the creation of the position of Vice President for the Palestine Liberation Organization (PLO) and the State of Palestine during a Palestinian Central Council meeting and the election of a new Secretary-General of the PLO executive community in May 2025, reflect an emerging effort to manage a political transition. These steps, alongside a constitutional declaration issued in late 2024 by President Mahmoud Abbas outlining succession procedures within the Palestinian Authority (PA), suggest a leadership seeking to manage a transition and shape the institutional contours of the next political phase.

These initiatives are taking place against a backdrop still defined by occupation, the absence of sovereignty, and ongoing internal fragmentation. At the same time, renewed international engagement on the question of the Palestinian state recognition, as seen most recently through discussions around the potential support of France and the United Kingdom—particularly in relation to the upcoming France-Saudi Arabia conference in June—has revived external interest in Palestinian governance and institutions.

In this context, I spoke with Dr. Sanaa Alsarghali, Associate Professor of Constitutional Law at An-Najah National University in Palestine, to explore the role constitutional mechanisms might play in shaping this transitional moment and whether the conditions for such reform will find a place and take hold.

With a collapsed ceasefire and competing proposals for Palestinian governance as of May 2025, what does the “Day After” really mean for Palestine?

In my opinion, for Palestinians, the “Day After” signifies more than a political transition; it raises deeper questions about stability, dignity, and long-term prospects. While international plans often focus on institutional reform, they tend to overlook the daily realities in both Gaza and the West Bank. Displacement, restricted access to essential services, and ongoing uncertainty continue to define the present. In this context, meaningful progress requires more than governance proposals; a proper “Day After” demands genuine engagement with Palestinian perspectives on rebuilding, rights, and imagining a future grounded in dignity.

There are various competing proposals on future post-war governance. What do you consider to be the most viable path forward?

Governance cannot be separated from sovereignty, and this remains the Achilles’ heel of many international plans. Palestinian sovereignty has been indefinitely delayed, and that delay has corroded governance. The PLO was established to represent all Palestinians, but the Oslo Accords created a model of nested sovereignty, with the PA operating in restricted spaces and under external constraints, which limited state-building process.

In terms of internal politics, the most urgent task is the reconciliation file. The Fatah–Hamas split has led to parallel structures in the West Bank and Gaza, weakening national cohesion. Reconciliation requires a shared vision, political will, and a renewed sense of unity. Governance plans, therefore, must serve as a platform for state-building, not merely administrative control.

The 2024 Beijing Declaration should have been used as a potential path forward, since it proposed a transitional unity government under the PLO. This framework was promising, but its success always depended on genuine reconciliation. At this stage, a technocratic government—backed by factions but not controlled by them—may be the most viable model. Its mandate would focus on service delivery and reconstruction, operating under the umbrella of the PLO.

Reform has been a long-standing Palestinian demand, both within the PLO and the PA. Yet many reform initiatives are shaped by external priorities. The 2024 U.S. call for an empowered prime minister echoes earlier efforts, such as the 2003 Road Map, when the role was introduced without sufficient legal grounding in the Basic Law. That structural gap created lasting tensions within the executive branch, particularly visible during the 2006–2007 period.

Palestinians must be the ones to lead this process; but what leadership will be accepted remains an open question. The challenge is not merely institutional. Palestinians continue to live under occupation, and over time, Israeli policy has systematically entrenched a one-state reality. This has made the prospect of a sovereign Palestinian state—central to the two-state solution—increasingly unviable, though no less justified or deserved. On the ground, the expansion of settlements, recurring military operations, and the fragmentation of Palestinian territory have extended Israeli control over nearly every aspect of daily life. A dense network of checkpoints, coupled with a system of differentiated identification cards, enforces a hierarchy of movement and rights: Palestinians in the West Bank and Gaza hold restrictive green IDs, while East Jerusalem Palestinians carry blue IDs—now considered residence permits—which offer relatively greater mobility but still fall short of full citizenship and political rights.

With limited control over financial revenues and other key levers of power, any governance proposal that does not address these structural conditions remains provisional at best. That is why I link any serious reform in governance to the broader question of sovereignty, and that is where international attention and pressure should be focused.

In November 2024, President Abbas issued a constitutional declaration on the question of the PA presidential succession. Although this development may have largely gone unnoticed, what is its significance in terms of the changes it introduces to Palestinian governance?

Constitutional declarations often emerge during transitional periods, and we saw many of them during the Arab uprisings. These declarations typically arise from interim governments, military councils, or heads of state to address legal gaps, functioning as provisional frameworks during crises. While these declarations are crucial for maintaining stability in politically unstable times, they are often criticized for centralizing power and limiting freedoms. This is still an area that needs more study and consideration.

In Palestine, President Abbas issued a brief constitutional declaration that addresses presidential succession. Unlike other declarations in the region that tend to cover a wide range of issues or declarations that serve as interim constitutions—like we saw in Syria now—the Palestinian one focuses specifically on one article that regulates the vacancy of the PA presidency.

The declaration requires further consideration because, while it should address only the succession of the PA presidency, it references two main institutions—the PA and the PLO—whose relationship remains complex. The dissolution of the Palestinian Legislative Council (PLC) in 2018 has further complicated the process, leaving the question of President Abbas’s interim succession—should a vacancy occur without elections—unclear.

The declaration names the Palestinian National Council (PNC) Chairman, currently Mr. Rawhi Fattouh, as the interim president of the PA. The PNC, which is the legislative body of the PLO, transferred its legislative powers to the Palestinian Central Council (PCC) in 2018. Established in 1973, the PCC has become the primary decision-making body within the PLO, and it is now responsible for electing members of the PLO Executive Committee (EC) and ensuring continuity of governance. The declaration also grants the PCC the authority to extend the interim presidency, removing ambiguity about decision-making during the succession process.

While the declaration aims to ensure the PA leadership continuity, it departs from the Palestinian Basic Law, which designates the PLC Speaker—not the PNC Speaker—as interim president for 60 days, with elections to follow (Article 37/2). The Basic Law, drafted in 1997 and ratified in 2002, was designed for a single legislative council during a transitional period expected to end in 1999 under the Oslo Accords. It did not anticipate scenarios where the PLC might become inactive or dissolved, creating ambiguity in succession procedures.

These gaps became particularly evident in 2006 when Hamas won the PLC majority, positioning its Speaker as interim president if a vacancy occurred. The PLC's suspension after the Fatah-Hamas clash in 2007, its dissolution in 2018, and the postponement of the 2021 elections—for various reasons such as Israeli government restrictions on the participation of Palestinians in East Jerusalem—have only deepened succession uncertainties. The Basic Law provides no alternative beyond Article 37/2, meaning a functioning PLC would have been required to amend succession rules. Had elections been held in 2021, a new PLC might have revised the law to offer clearer alternatives.

In summary, the PA presidential succession declaration seeks to maintain governance continuity in the absence of a functioning Palestinian Legislative Council (PLC). It could be seen as an amendment to the Basic Law—an act that, according to procedure, requires the approval of at least two-thirds of PLC members. However, the declaration is not so much a formal amendment as it is a temporary measure to fill a constitutional gap—one that could be properly addressed once legislative life resumes, should elections be held and a functioning Legislative Council be restored.

How does this declaration affect the balance of power between Palestinian institutions?

Good point, the declaration raises several unanswered questions. What happens if the PCC extends the temporary 90-day period, but elections still do not take place? While the declaration calls for elections, the election law itself presents challenges. Under the 2021 amendment of the election law, only the President of the State of Palestine and the PLO Chairman have the authority to call for elections. However, since the declaration appoints the PNC Speaker as interim PA President (since the Basic Law applies to the PA and not directly to the State or the PLO), it is unclear whether he has the legal power to do so. If not, must the PLO Executive Committee elect a new chairman within 90 days to do so? In this regard, the declaration’s wording is unclear. Although some proposed appointing a Vice President to ease the transition, the idea was rejected at the time, but later got accepted. Therefore, under the amended election law, the question of who would call for elections was not previously contested. Like the late President Arafat, President Abbas holds all three positions—President of the PA, Chairman of the PLO, and President of the State of Palestine—so the leadership roles were unified and never subject to division. However, the recent declaration concerning the PA presidency alone has now opened the discussion on who holds the authority to call such elections—an issue that the declaration itself should have considered.

Even if succession is clarified within the PA, another issue remains: under the 2021 law, presidential candidates must commit to the PLO, the Declaration of Independence, and the Basic Law. If someone outside (the PLO Executive Committee—or the newly elected chairman) wins the PA presidency, it could lead to a split between the PA and the PLO leadership. This would deepen institutional fragmentation and political instability at this stage, which, in my academic opinion, is not the time for it without a proper transition towards statehood.

On 24 April, the Palestinian Central Council announced the creation of the position of Vice President for both the PLO and the State of Palestine. This step followed an announcement by President Abbas during the March 2025 Arab Summit. How does this affect succession planning and the broader reform agenda required from the Palestinian leadership?

Correct; at the Arab Summit, President Abbas announced plans to establish a Vice President position for both the PLO and the State of Palestine. At first glance, this move appeared to be an attempt to create a clear line of succession within the PLO, possibly to manage anticipated rivalries within the Executive Committee in the event of a leadership vacancy. In addition, to broader external demands for reform.

However, challenges exist both before and after the creation of this role. The key legal issue is that no such position exists in the PLO’s Basic Order (Al-Nizam Al-Asasi). Amendments to that foundational document must be made by the Palestinian National Council (PNC), not simply approved by the Palestinian Central Council (PCC). Therefore, the PCC’s approval of the Vice President position can be interpreted in several ways. If the duties of this role—left undefined at the time of appointment—are eventually clarified, the creation of the position could offer a quicker and more structured mechanism for leadership transition and reduce uncertainty during periods of political instability.

Beyond this procedural concern, the appointment raises broader legal and constitutional questions. If we consider the President of the Palestinian Authority (PA) to be the same as the President of the State of Palestine—given that, following the UN’s 2012 recognition, all internal legal references to the PA were replaced by “State of Palestine” in 2013—then the Vice President role should logically extend to the PA as well. However, no such position exists in the Palestinian Basic Law, which governs the PA, and any major amendment to it would likely provoke further criticism of the leadership’s reform agenda.

As previously noted, the succession declaration was not a formal amendment; rather, it sought to operate alongside the Basic Law. It notably bypassed the article that designates the Speaker of the Palestinian Legislative Council (PLC) as the successor. Despite this constitutional irregularity, the reference to the Speaker of the PNC in the declaration could arguably find some legal grounding in the Basic Law’s preamble, which recognizes the PNC and affirms the PLO’s institutional primacy. If one interprets the preamble as having constitutional value, then a weak—but not entirely unfounded—legal basis may exist for naming the PNC Speaker as the interim authority in the absence of the PLC.

Moreover, a 2007 presidential decree designated all PLC members as members of the PNC, and at the time, even Hamas did not object to this arrangement. One could argue, then, that the PNC functions as the upper legislative chamber and the PLC as the lower house, representing Palestinians within the territory. In that light, the appointment of the PNC Speaker as interim president might be less controversial than the creation of the Vice President role itself.

Nevertheless, the Vice President role was created for both the PLO and the State of Palestine. As a result, our understanding of its political implications—and how it fits into the broader succession framework—will depend, as previously noted, on the clarification of its functions (which may evolve over time) and on the interplay of internal and external political dynamics.

As of now, there appear to be no changes to the procedures governing a vacancy in the Chairmanship; the Executive Committee of the PLO remains the body responsible for electing the successor. The new Vice President role does not entail automatic succession to the Chairmanship. Thus, the challenges raised by the declaration—including the ambiguity over who holds the authority to call elections under the current electoral law (which assigns that power to the Chairman of the PLO and the President of the State of Palestine, typically the same individual)—remain unresolved by the creation of this new post.

The Vice President position does not confer interim presidential or chairman status, nor is it clear whether it functions merely as a deputy role within the current political system or is intended as a long-term institution. Consequently, further time and clarification are needed to understand how this position will ultimately fit into the overall constitutional and political framework.

That said, constitutional conversations and solutions differ significantly from political debates and priorities at this stage—something that will affect how both the declaration and the creation of the Vice President post are interpreted, depending on which dimension one considers.Some argue that the declaration and the creation of the Vice President post are President Abbas’s way of “arranging the internal house” while still in office. What happens next, however, is still unclear.

Personally, I would argue that the recurring problem with the Palestinian reform debate is that it constantly revolves around who will hold power, rather than how that power should be exercised. International actors also tend to focus heavily on the who. But as long as the discussion remains centered on individuals rather than on institutional and constitutional development, meaningful and lasting political reform will remain out of reach.

In light of this, how relevant are other constitutional conversations now?

Constitutional conversations are incredibly relevant. While discussions on reconciliation, unity, and the type of government are essential, the legal framework should not be overlooked. Constitutional tools can serve both as a means of reconciliation and a product of unity agreements; it works both ways. This is where the concept of a transitional or interim constitution becomes crucial.

Nathan Brown and I have written on this, arguing that an interim constitution could establish a functioning legal system. For instance, it should address key issues such as the relationship between a future Palestinian state and the PLO, as well as the role of the PA. We often say we are transitioning from the PA to statehood (Sulta to Dawla). However, from a constitutional standpoint, we are not there yet, especially at this stage, where such a transitional link is essential. Some may argue that the Basic Law already exists, so why focus on drafting something new? My response is that the Basic Law was never intended to govern the next stage, nor is it a permanent document or a document suited for the future phase.

You might ask: who should draft the interim constitution? Ideally, this task should fall to constitutional experts, supported by political factions but not dominated by them. And you might ask: when can this process start? First, in my opinion, a national dialogue must take place—though this may now be more difficult than before, especially if it is to be inclusive, given the recent declarations by President Abbas following the Arab Summit in Baghdad, and the uncertainty over whether Hamas will accept such a proposal. Yet, if such a dialogue were to occur then, then the drafting should translate political agreements into a functional legal framework for the next stage. Elections are necessary, but without a clear division of powers between the President and Prime Minister—or clarity on the new vice-president role—we risk repeating past deadlocks. Again, there’s still a chance to use the interim constitution as a constructive tool, but it requires serious, inclusive dialogue. Even if the dialogue is limited, Palestinians still need a new constitutional framework to provide clarity on the next phase. The process may face criticism over how it begins and who leads it, but an interim document is essential to guide the transition. For this to actually happen, it will require both political will and international support. This is not too much too soon; it’s a long-overdue conversation.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Disclaimer: Opinions expressed in this interview are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the institutional position of International IDEA, its Board of Advisers or its Council of Member States.