Election technology: precondition for transparent elections or pretext for questioning electoral integrity?

Disclaimer: Views expressed in this commentary are those of the staff member. This commentary is independent of specific national or political interests. Views expressed do not necessarily represent the institutional position of International IDEA, its Board of Advisers or its Council of Member States.

More and more countries around the world, including many developing democracies, increasingly embrace technology to strengthen their electoral processes. Clearly there are setbacks, including – prominently – this year’s presidential election in Kenya, which was annulled due to “irregularities and illegalities inter alia, in the [electronic] transmission of results”. But as technology matures, some expect that, sooner or later, fully automated elections will become unavoidable and even a requirement for a credible and transparent electoral process.

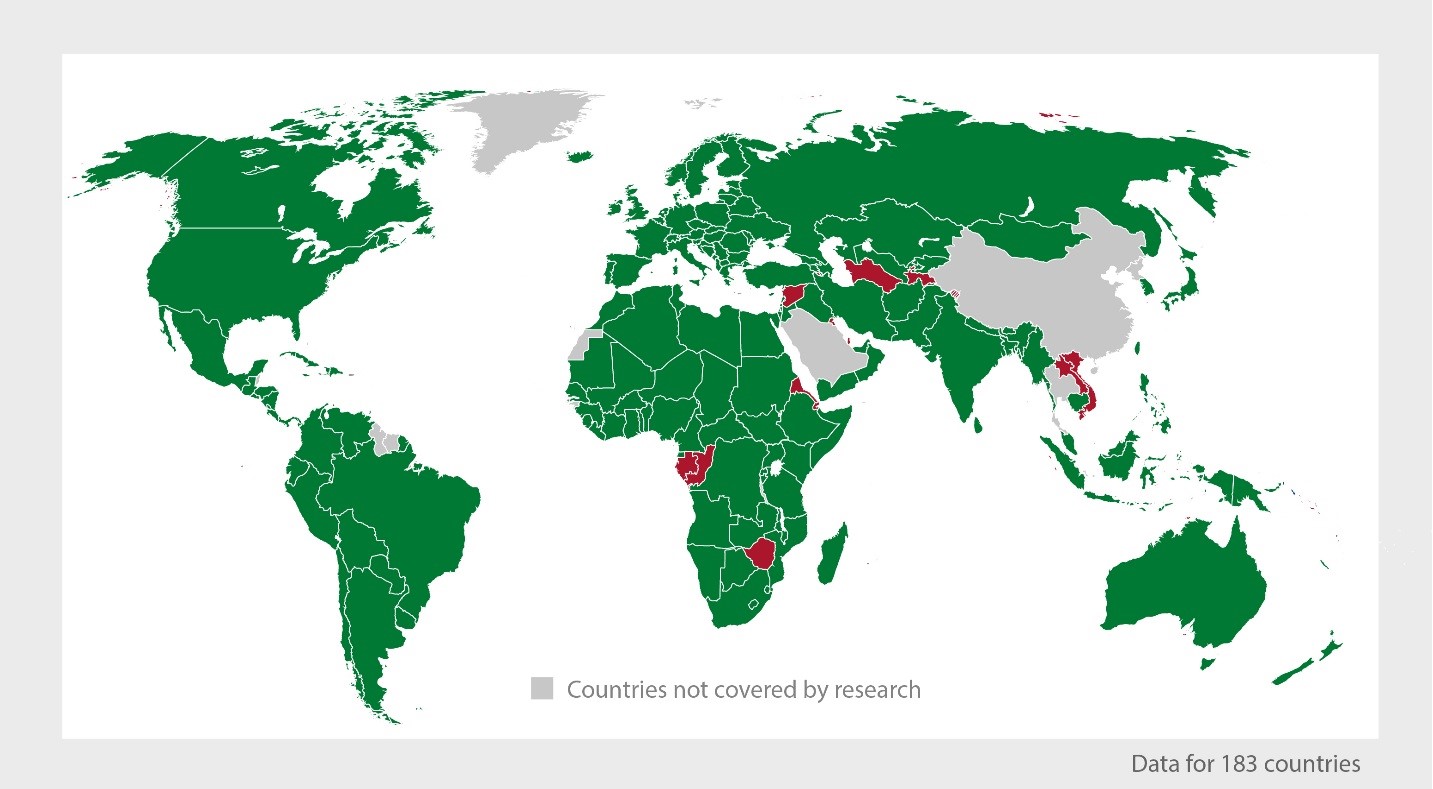

International IDEA’s global data on the use of ICTs in elections around the world provides a first snapshot of the current situation: only very few countries (about 11%) conduct elections largely without technology (Figure 1) and using at least some technology is already now a reality for most election administrations.

Figure 1. Do countries use technology in election administration?

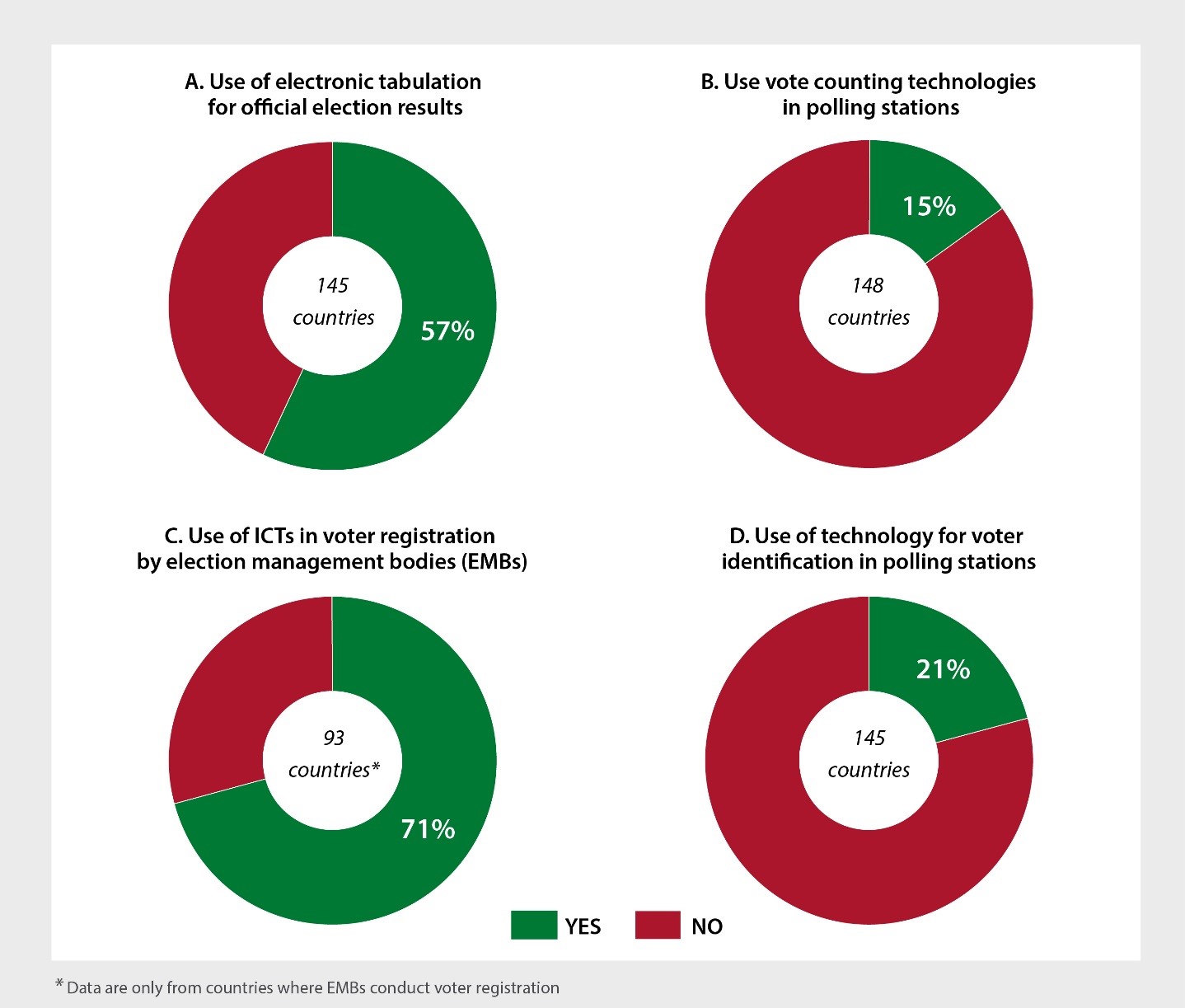

Taking a closer look at this data, however, reveals big differences depending on the type of technology in question. While around 57% of surveyed countries use electronic tabulation systems for official results (Figure 2A), only 15% of countries use vote counting technologies in polling stations (Figure 2B). While 71% of election management bodies responsible for voter registration utilise ICTs for this task (Figure 2C), only 21% of countries also use technology for voter identification in polling stations (Figure 2D). So, at least for now, fully automated elections are the exception rather than the norm.

Figure 2. Use of ICTs in various stages of election administration

But what will happen in the future? What technologies can be expected to become mandatory for credible and transparent elections? Arguably, this will depend on at least two key factors: on the difference the various types of technologies can make in increasing electoral integrity and on how efficiently the technologies can be applied.

In terms of efficiency, technology applied at central level has a clear advantages: only a limited amount of devices need to be deployed and maintained in locations where infrastructure and security can easily be provided. Online result publishing systems that allow detailed access to electoral data are amongst the systems that can be easily deployed and greatly enhance the transparency of elections. The use of such systems and the application of related open data principles can therefore be expected to become increasingly demanded and expected from election administrators.

As election technology gets closer to polling stations, hardware, infrastructure, training and capacity-building needs increase rapidly. With this, the local context becomes progressively more relevant for determining technological effectiveness. This starts with result transmission and aggregation systems: about 15% of countries transmit results electronically from online connected polling stations. The large majority only capture results electronically at municipal level or higher. Many of these countries, including well established democracies, are satisfied with the speed and accuracy of this partially manual process and see, for now, no need to upgrade related technologies.

Technology at polling-station-level can only be effective where it provides a solution to well-defined, major challenges in a given country context such as complicated ballots, a slow vote count, and inaccuracies or even manipulation in manual procedures. Where such challenges exist, the effort of deploying technology may well be justified by improved speed, accuracy, automatic enforcement of polling station procedures and detailed event logging, which can all contribute to a more trusted and transparent election.

However, with ICTs deployed in polling stations the transparency of election technology itself increasingly becomes the focus of stakeholder attention. Transparent elections require that all steps of the process are open and can be followed and verified by stakeholders. Simple visual verification of the proper functioning of technology is often difficult or impossible.

Where technology in polling stations becomes the norm, so too will the need for additional transparency mechanisms including broad stakeholder consultations, feasibility studies, open procurement processes, technology certification or opening-up source codes. In the absence of such mechanisms, especially in highly contested and low trust contexts, allegations of manual fraud may simply be replaced by allegations of technology manipulation and hacks. Once the integrity of elections can be questioned by such allegations, it becomes somewhat irrelevant whether any such irregularities did indeed occur and whether they actually impact on the election results or not.