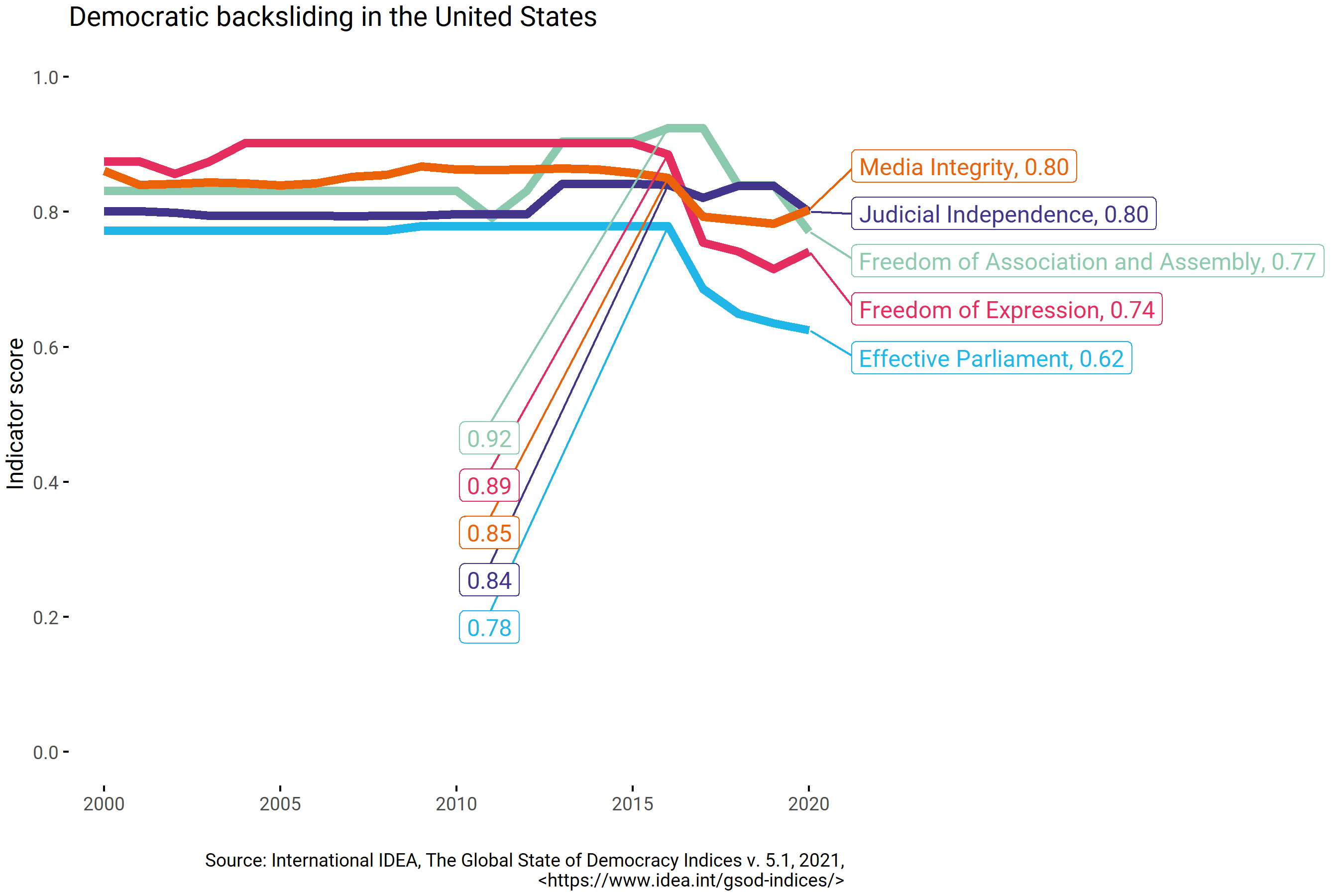

In International IDEA’s recently published report on The Global State of Democracy 2021, one of the most remarked-upon findings was that the United States of America is now a backsliding democracy. While many people have a relatively intuitive sense of what democratic backsliding means, the underlying causes and potential outcomes deserve some further exploration.

By democratic backsliding, political analysts generally mean that a democracy is slipping backwards in terms of its democratic performance, and that there are signs of rising authoritarianism. One succinct definition holds that democratic backsliding involves “state-led debilitation or elimination of any of the political institutions that sustain an existing democracy.” Democratic backsliding differs from more generalized democratic erosion in terms of both intent and focus. International IDEA’s research in this area has highlighted the linkage between democratic backsliding and actions that specifically damage both horizontal constraints (via attacks on the legislature and the courts) and accountability to the voting public (via interference with media integrity and civil liberties).

In most cases of democratic backsliding, the ability to hold free and fair elections is not immediately impacted – though this may come later. Applying the implications of this research in a diagnostic way, International IDEA tracks the average value of its indicators for Checks on Government and Civil Liberties for every country, and where we see a decline compared to five years ago that is greater than the threshold we’ve defined, we classify that country as backsliding. That also means that each country is compared to itself, not to some abstract and universal standard.

In our analysis of the United States (one of seven backsliding countries in 2020: Brazil, Hungary, India, the Philippines, Poland, and Slovenia), we show that while the country performs very well across many indicators of democracy, there are significant and serious declines in these vital parts of the democratic system, and there is reason to be worried about the trajectory of the country. By analogy, it’s a bit like someone who appears to be very physically fit, but has very high cholesterol. An individual is healthy in many ways, but s(he) is at high risk of a serious medical incident.

One of the most notable trends in the United States in the last five years has been a decline in what we call Effective Parliament. The inability of the US Congress to check the executive or investigate the actions of former-President Trump – even after the change in the majority party after the 2018 midterms – is reflected in a sharp decline in this indicator in 2017 and following. At the same time, police brutality in response to protests (particularly those organized by the Black Lives Matter movement) led to a rapid decline in the Freedom of Association and Assembly.

Unlike the concerted legislative effort to disempower or capture institutions that has taken place in other backsliding countries (e.g., Hungary), the US experience with democratic backsliding appears to have more to do with political and institutional weaknesses that came to light when an illiberal leader pushed the limits of what had previously been understood to be acceptable in US politics. However, the departure from office of that leader does not mean that US scores will immediately rebound. As the problems identified were not primarily legislative, they cannot be legislatively corrected. The US Congress must improve in its ability to fulfil its functions, and governments at all levels in the United States must recommit themselves to the protection of Civil Liberties for all Americans in order for this backsliding episode to be reversed.

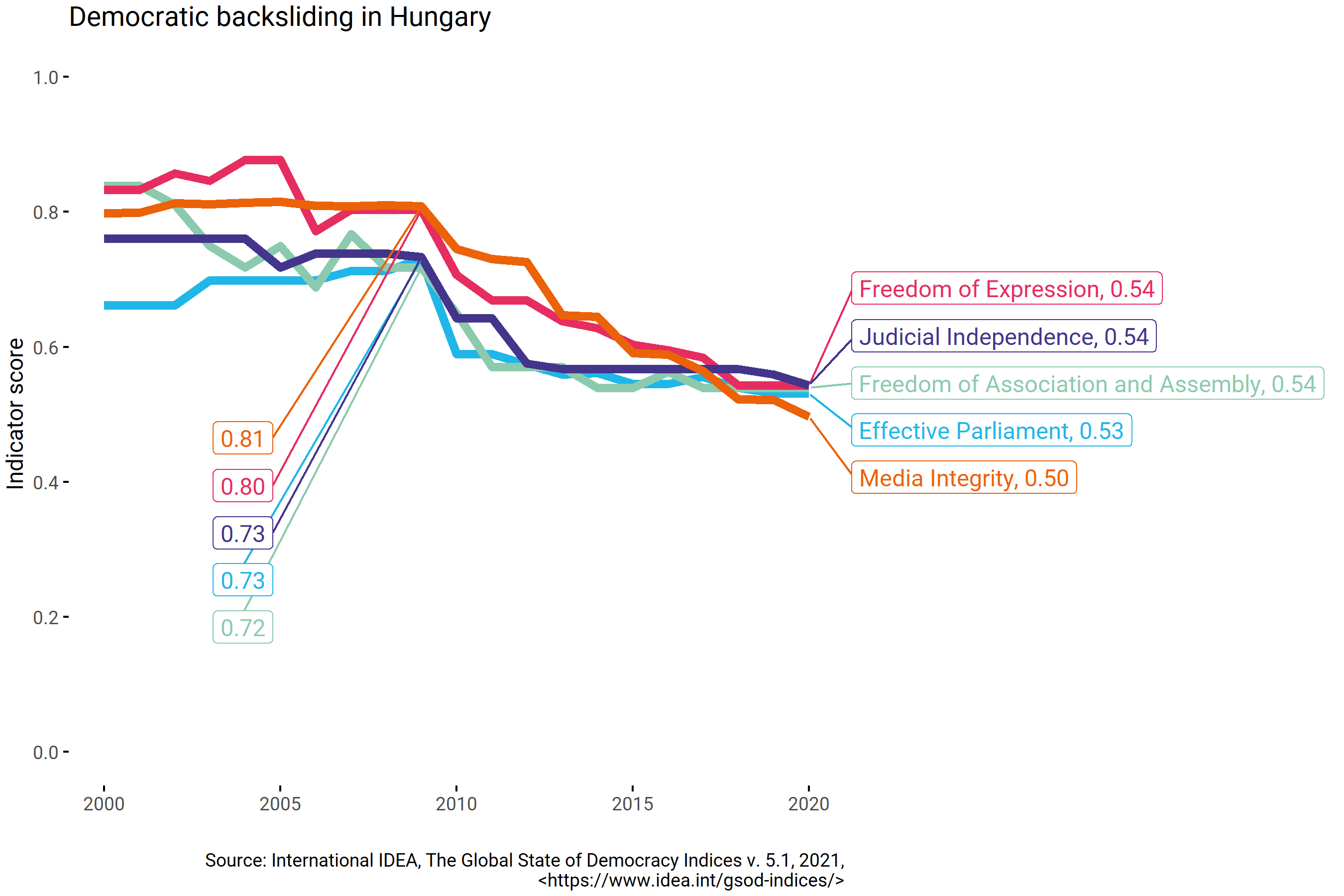

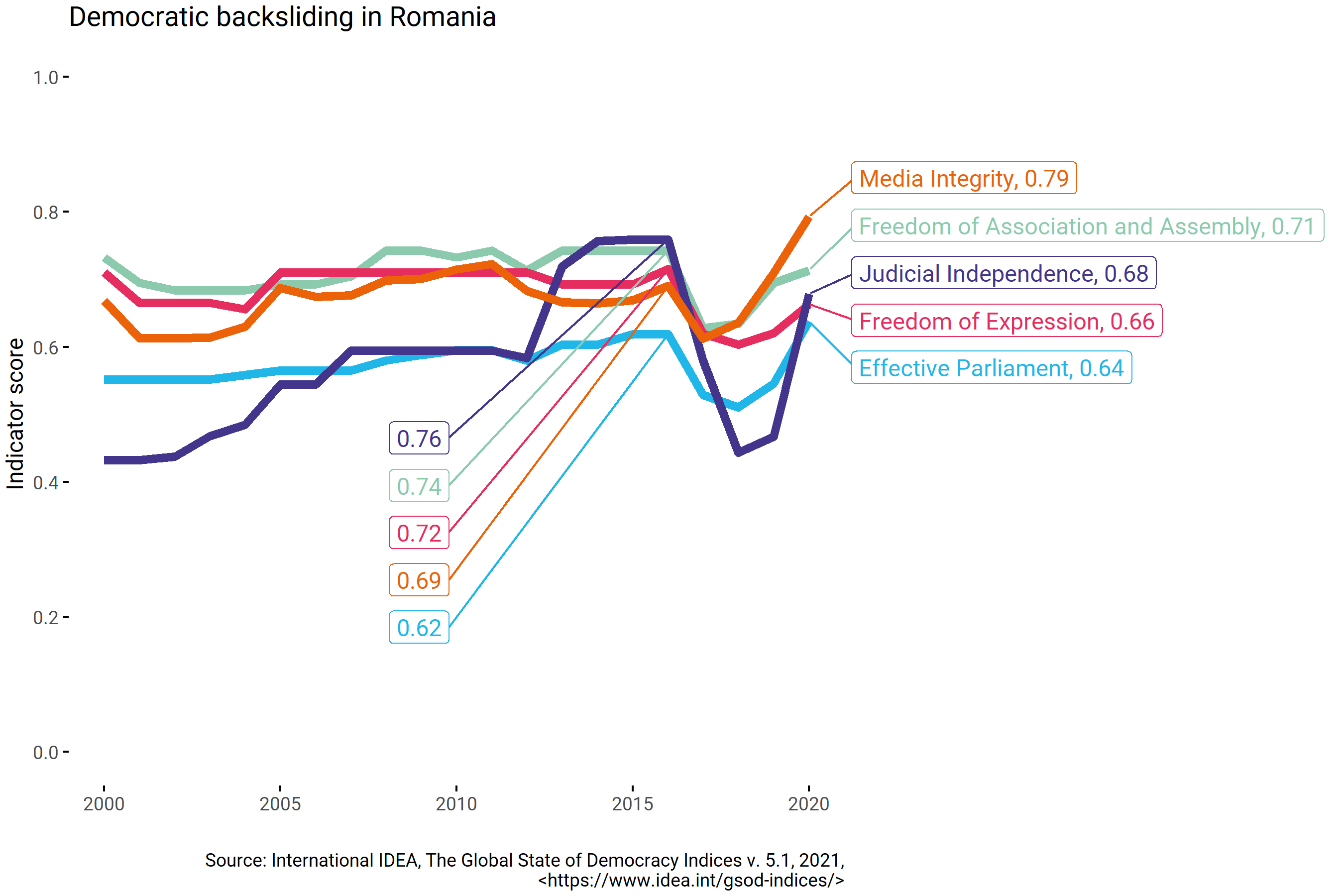

The United States is far from being the only backsliding democracy that we’ve observed, and (as noted above) it is one of seven countries in the midst of a backsliding episode in 2021. This provides us with enough comparative data to consider how backsliding episodes vary in their causes and outcomes. After several years of democratic backsliding, Serbia became a hybrid regime in 2020. In contrast, after only two years of democratic backsliding, Romania (discussed below) began to improve again in 2020. Hungary provides an example of prolonged democratic backsliding that has stabilized into a severely flawed form of government.

Hungary has been a roundly condemned example of democratic backsliding over the last decade, and the country’s experience with a deliberate transition to “illiberal democracy” illustrates one common path. Since Fidesz returned to power under the leadership of Viktor Orbán in 2010, the party has pursued the consolidation of power through legislation that has weakened the judiciary, attacked civil liberties and academic and media freedom, and in other ways weakened the ability of the legislature to check executive power. The declines in key indicators of backsliding happened at first suddenly in 2010, and then more gradually until the present. Hungary seems to be stabilizing at mid-range performance in these indicators – neither sinking further nor improving.

Romania’s experience with democratic backsliding began in a manner similar to Hungary, but was very short-lived. In late 2017, a series of laws were passed by the Social Democratic Party (PSD) government -- led by party chairman Liviu Dragnea – that would have severely undermined judicial independence and anti-corruption efforts. The public responded to these legislative moves with some of the largest protests in many years. Hundreds of people were injured in clashes with police during those protests, leading to calls for the EU to take action to protect civil liberties in Romania. However, following a change of government in 2020, the new National Liberal Party (PNL) government took steps to reverse the challenges to judicial independence that began in 2017. Romania’s performance improved across a range of indicators in 2020, ending the backsliding episode very quickly, though Romania’s democracy continues to face many challenges.

Democratic backsliding most often involves a deliberate campaign to undermine institutions, close civic space, and restrain the media. Sometimes this has been pursued through targeted legislation; in other cases demagoguery and intimidation have been the favored methods. The varied paths of democratic backsliding indicate that the solutions will vary as well. In The Global State of Democracy 2021 Report, International IDEA laid out a number of policy recommendations for reinforcing and revitalizing democracy.